Oxford University Press's Blog, page 539

March 7, 2016

Who should be Scalia’s new successor?

Article III of the Constitution gives the President the right to “nominate…Judges of the supreme Court.” Article III also gives the Senate the right to grant its “Advice and Consent” to such nominations—or not. Both President Obama and Senate Republicans are settling into a protracted political struggle over the appointment of Justice Scalia’s successor.

In the grand scheme of American history, this should neither surprise nor alarm us. Partisan considerations often loom large in appointments and confirmations to the Supreme Court. The role of the Court is a legitimate issue for popular discussion. Indeed, the quintessential lawyer-politician of American history, Abraham Lincoln, emerged as a national political figure in large part by criticizing the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision.

However, the Court stands for other vital values as well: the rule of law and constitutionalism as principled decisionmaking. While the Court is an institution of government, it also embodies the law. We expect more from the Supreme Court than political expedience.

In short, the Court is simultaneously two different institutions, the inherently political third branch of the federal government and the protector of the rule of law.

How should we reconcile these conflicting demands under current circumstances? The Court’s recent decision in Noel Canning suggests the best way to manage the conflict about Justice Scalia’s successor. As they tussle over the identity of that successor, the President and Senate Republicans should agree on a recess appointment by which one of the three living former justices temporarily returns to the Court. Such an appointment would affirm that the Court, while a political entity, is also the guardian of the rule of law.

In Noel Canning, the Court held that the President’s power to make recess appointments is triggered when the Senate declares itself to be in recess. The Senate currently avoids such a declaration by holding nominal sessions at least every third day. The evident purpose of the Senate’s practice is to preclude the President from making recess appointments.

The Senate could agree with President Obama that the Senate will recess for the limited purpose of enabling the President to reappoint to the Supreme Court one of the three living former justices, Sandra O’Connor, John Paul Stevens, or David Souter. This temporary appointment would immediately bring the Court up to full strength. Under the Constitution, this appointment would automatically “expire at the End of [the Senate’s] next Session.”

At that point, either President Obama’s nominee will have been confirmed or it will be clear that the selection of Justice Scalia’s successor will be made by the next President.

Placing one of these iconic figures back on the Court would make an important statement about the rule of the law and the Court’s role as the protector of principled constitutionalism. While political debate over Justice Scalia’s successor would proceed, the Court would also continue to do its business with a full complement of nine justices.

There would be no learning curve for any of the three former justices. Any of the three would be a full participant in the Court’s work from day one. Moreover, a former justice, returned temporarily to the Court, would likely be particularly sensitive to the weight of the Court’s prior decisions. Adherence to precedent is an important value of the rule of law.

A recess appointment for a former justice has never occurred before. But a recess appointment to the Supreme Court would not be a novelty. President Eisenhower first appointed William J. Brennan, Jr. to the Court through a recess appointment.

I suspect that none of the three former justices would be excited about accepting the proposed recess appointment. Each of them enjoys a well-deserved retirement from public life.

However, the former justices are uniquely positioned to accept temporary assignment back to the Supreme Court through a recess appointment. Such an appointment of a former justice would help affirm that, even as the nomination and confirmation of Justice Scalia’s successor generates partisan struggle, the Court can conduct its business as usual and thereby protect the rule of law.

Image Credit: “The Supreme Court” by Davis Staedtler. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Who should be Scalia’s new successor? appeared first on OUPblog.

How filling the Supreme Court vacancy will affect public health

Who is selected to fill the vacancy on the Supreme Court will profoundly affect key public health issues, including gun control, access to reproductive health services, and climate change. In recent years, the Court has ruled, usually by 5-to-4 decisions, on these issues and will likely continue to do so by narrow margins. Whoever fills the vacant seat is likely to tip the balance, one way or the other, on future Court decisions related to these issues.

Handguns account for 33,000 deaths annually in the United States. Gun control, such as restricting gun ownership, has been demonstrated to be a successful method for reducing these fatalities. The Supreme Court in recent years has overturned municipal ordinances in Chicago and Washington, D.C., that banned residents from keeping handguns at home for the purpose of self-defense. These decisions have led to weakening of other gun-control laws and regulations in states and communities across the country. In the near future, the Court is likely to hear more cases related to the availability and accessibility of handguns – and therefore related to the epidemic of gun-related violence in this country.

In recent years, the Court has made many decisions that have chipped away at a woman’s right to choose, which is supported by the Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade decision. Now providers of healthcare for women are asking the Supreme Court to repeal a 2013 state law in Texas that mandated new requirements for facilities where abortions are performed. That law would likely lead to the closure of more than three-fourths of these facilities and prevent the opening of new ones. More cases on access to contraception, access to abortion services, and other reproductive rights and reproductive health services will come before the Court in the foreseeable future. How the Court decides on these matters will have profound effects on the health and well-being of women and their families.

The Roberts Court (October 2010 – February 2016). Front row (left to right): Clarence Thomas, Antonin Scalia †, John Roberts (Chief), Anthony Kennedy, Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Back row (left to right): Sonia Sotomayor, Stephen G. Breyer, Samuel A. Alito, Elena Kagan. Photo by Steve Petteway, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Roberts Court (October 2010 – February 2016). Front row (left to right): Clarence Thomas, Antonin Scalia †, John Roberts (Chief), Anthony Kennedy, Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Back row (left to right): Sonia Sotomayor, Stephen G. Breyer, Samuel A. Alito, Elena Kagan. Photo by Steve Petteway, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Climate change is increasing the occurrence of heat-related disorders, exacerbating chronic respiratory and allergic conditions, vector-borne and other infectious diseases, injuries due to extreme weather events, collective violence, mental health problems, and, due to food insecurity in drought-stricken regions, malnutrition. Emissions from coal-fired power plants are a major source of greenhouse gas emissions, which are the major cause of climate change. The Supreme Court, which recently stayed President Obama’s executive order to restrict emissions from coal-fired power plants, will ultimately review the constitutionality of this order and, more generally, the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to regulate greenhouse gases. The global leadership of the United States on climate change is vitally important. Unfortunately, the Court’s stay of the President’s order is delaying US implementation of the climate-change agreement to which 195 nations agreed in Paris just two months ago.

Arguably, the justice who fills the vacant seat on the Supreme Court will have more impact on public health for the next several years – or longer – than the Surgeon General or the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As long as the seat is not filled, the Court will likely be deadlocked on gun control, access to reproductive health services, and climate change – and perhaps other issues impacting public health. Decisions on these important issues should not have to await the results of the presidential and senatorial elections in November.

Public health has been defined as what we, as a society, do collectively to assure the conditions in which people can be healthy. How the vacant seat on the Supreme Court is filled will have a profound effect on how our nation assures – or fails to assure – the conditions in which people can be healthy.

Featured image credit: Supreme Court by Mark Fischer. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How filling the Supreme Court vacancy will affect public health appeared first on OUPblog.

Risen the Movie: a scholarly review and comparison

The film Risen retells the story of Jesus’ resurrection and ascension through the fictional Roman tribune Clavius, who supervises both Jesus’ crucifixion and the investigation into what happened to his missing body. Clavius’ encounter with the crucified Jesus, his interviews with enthusiastic disciples and other witnesses, and finally his encounters with the risen Jesus lead him to embrace faith.

Risen has ancient precedents. Early Christians created fictions of their own, testifying to Jesus through the perspective of Pontius Pilate. The Acts of Pilate and the Epistles of Pilate show a Roman prefect deeply troubled by Jesus, whom he sends to the cross. In the Acts of Pilate, Roman standards bow when Jesus enters the room, attesting to his holy identity. The Epistles of Pilate even portray him as a Christian convert. Risen, like its ancient predecessors, proclaims the gospel through the eyes of the Romans who killed Jesus.

Risen strings its story line through bits and pieces selected from the gospels, and as each of the Christian Gospels presents its own interpretation of Jesus, so does the film. One might describe this Jesus as “romantic”; he compels faith through the force of his presence. Jesus speaks little in the film, but even a look into his dead face takes hold of Clavius. Pontius Pilate sends Jesus to the cross but orders his legs broken in order to shorten the agony. (In John’s gospel, Pilate does so to placate the Jewish leaders.) Clearly shaken by his encounter with Jesus, Pilate issues this order while washing his hands. Jesus does take moments for one-on-one mentoring. When he does so with Clavius, he comes across like the perfect pastor or therapist, asking just the right questions and offering support.

The Jesus of Risen is largely spiritual. His teachings boil down to simple love. And he is harmless. One wonders why anyone would want him dead, since he poses no direct threat to the authorities. Pilate himself remarks on this: “It’s as if he wanted to be sacrificed.” The idea that Jesus sought his death may be common in popular piety, but it is foreign to the gospels.

Like most Jesus movies, Risen picks and chooses among the gospels to create its narrative. During the crucifixion, we witness Matthew’s earthquake and overhear Jesus’ triumphant last words from John: “It is finished!” We do not hear his final cry from Mark and Matthew: “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” The resurrection story includes the cover-up plot from Matthew, as well as two disciples’ encounter with the risen Jesus from Luke. As Jesus prepares to ascend, he utters quotations from John, Acts, and Matthew.

Such harmonization creates awkward moments. Risen quotes the promise (from Mark 16:7) that the risen Jesus will meet his disciples in Galilee. But only the author of Luke narrates Jesus’ ascension into heaven, and Luke places Jesus’ resurrection appearances in and around Jerusalem. In Risen, Jesus’ ascension very much resembles a space launch, but it occurs in Galilee. Mark knows nothing of Jesus’ ascension, and Luke describes no resurrection appearances in Galilee, but Risen blends the two. This kind of selective blending obscures the distinctive witness of each gospel, and it results in a Jesus who resembles none of the four gospels.

Risen does have its silly moments. The Shroud of Turin appears twice, with Jesus’ image burned into his burial cloth. We encounter the common portrayal of Mary Magdalene as a prostitute, for which there is no biblical evidence. In one scene, Claudius asks how many of his troops know Mary, and one by one his soldiers raise their hands. We have chase scenes and a battle scene; Risen portrays the period as if, fueled by messianic fervor, Jews were waging pitched battles against the Romans.

There were no such battles, and we do not know how many Jews expected a messiah or what exactly they expected. As in the gospels, the film portrays the temple authorities as hopelessly hypocritical and manipulative. Pilate even calls them out for visiting him on the Sabbath. Almost all Jesus films convey an anti-Jewish bias, and though Risen does better than most, it still conveys the impression that Jews missed out on the messiah due to their own cluelessness and their leaders’ duplicity—an assumption that has accompanied great evil over the centuries.

Like the gospels, Risen tells the Jesus story in order to inspire its audience through its interpretation. Unfortunately, although it does draw upon these gospels for its portrait of Jesus, the Jesus of Risen doesn’t much resemble the one we meet in Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John.

Image Credit: “Affreschi di Gaetano Bianchi sulla lunetta della Cappella Gentilizia Corsini (Villa Le Corti), San Casciano Val di Pesa” by Vignaccia76. CC BY SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Risen the Movie: a scholarly review and comparison appeared first on OUPblog.

Leap day, giant viruses, and gene-editing

2016 is a leap year. A leap year, or intercalary year, is a year with an extra day inserted to keep pace with the seasons. In the Gregorian calendar this falls every four years on Feb 29th.

On Leap Day this year a wonderful piece of science was published about an equally rare part of nature – giant viruses. Just as a leap day adds the essential nuance to a human devised system making it accurately reflect the physical world, this study bolsters our knowledge of the machinations of the biological world.

And the implications are potentially profound. Giant viruses, namely the mimiviruses, turn out to harbour a gene-editing system.

Gene-editing is being compared to the moon landing, is a strong contender for a Nobel prize, has been used to reverse the cancer of a toddler, and brings with it potentially dystopian visions of designer babies and eugenics.

The gene-editing story started not in the field of medicine, or even human genetics, but in the field of environmental microbiology. Gene-editing systems, now used by humans to artificially modify organisms, such as pet micro-pigs, are used as immune systems in bacteria.

The most popular form of gene-editing, CRISPR-CAS, was originally identified, compared across microbes (Archaea and Bacteria) and given a name by Francisco Mójica, a microbiologist, in the 1990s. He noted that Japanese researchers had observed repetitive CRISPR sequences in E. coli as early as 1987.

Micro pig, by LWP Kommunikacio. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Micro pig, by LWP Kommunikacio. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.By 2008, CRISPR sequences had surfaced in a range of complete bacterial genome sequences and researchers understood their function. They were a defence system that sought out and destroyed viruses.

Viruses of bacteria are called phage, and phage constitute the most abundant biological entity on Earth. Estimates suggest 10 phage exist for each type of bacteria and bacterial cells are more abundant on this planet than stars in the Universe.

Not discovered until 2003, the first giant viruses, mimiviruses rewrote the textbook on what it means ‘to be a virus’ – or not. Mimiviruses are huge. At almost half a micrometre in diameter, they are big enough to be viewed with a light microscope. This is in the size range of bacteria and they were originally misclassified, part of the reason they escaped formal recognition for so long.

The first proof of the existence of mimiviruses came from a sample of amoebae living in a water tower in the UK, which were thought to be ‘just bacteria’, and so stuffed away for safe-keeping. Once retrieved by microbe-hunter Didier Raoult, they were found to be the first representatives of a family of giant viruses that attack amoeba.

Giant viruses are some of the most intriguing and mysterious biological entities left to explore in the natural world. They blur the line between living and non-living. Viruses are non-living because they need a host genome to replicate; living organisms are defined by their ability to self-replicate.

Giant viruses look enough like viruses to be classified as distantly related to a group of viruses that includes smallpox. Yet, they do far more than traditional viruses with their large repertoires of genes, like create their own amino acids. Mimiviruses hold record numbers of novel genes. The metabolisms and activities of these biological entities remain largely unexplored and unknown.

It’s a dog eat dog world. While giant viruses attack amoebas, they in turn are attacked by virophages, further evidence that giant viruses are ‘alive’.

In 2014, the discoverer of the Mimiviruses, virophage and giant virus champion, Didier Raoult and his colleagues found the Zamilon virophage. It selectively infects some mimiviruses but is harmless to others. This discrepancy led Raoult to speculate that mimiviruses harboured a defence system. He modelled his concept on the ‘immune-system’ defences of bacteria.

Raoult sequenced 59 mimivirus strains searching for telltale Zamilon DNA. He searched for the signature pattern of a defence system like CRISPR. CRISPR-CAS systems comprise a set of ‘adopted’ phage sequences that are ‘remembered’ after an infection and an enzyme that can chop up those sequences if the same phage invades again. The more phage attack a bacterium, the more ‘mimic sequences’ it will store up in its library of ‘foreign DNAs to attack’.

Mimviruses use the same strategy. Raoult found snippets of Zamilon sequences in ‘protected’ strains. Adjacent to these sequences lurked an enzyme able to unwind and degrade DNA, the smoking gun.

Destroying parts of this CRISPR-CAS-like system made mimivirus strains vulnerable to Zamilon infection again.

The next step after identifying what Raoult calls the ‘MIMIVIRE’ system is to figure out exactly how it protects the giant virus genome by stopping virophage infections.

Raoult has gone as far as to suggest that giant viruses are not actually viruses at all, but a fourth domain of life. While his argument is contentious, he suggests that this ‘MIMIVIRE’ system supports his theory. He believes giant viruses belong on their own, ancient branch of the Tree of Life.

Just as we need an extra day every four years to keep our calendars in working order, what else might we discover before we understand the reality of the biological diversity found in nature?

The study of giant viruses, and the discovery that they too possess a gene-editing system, offers a gentle reminder of how important the “rare” can be – an especially satisfying scientific way to celebrate Leap Day 2016.

Featured image credit: Bacteria, by geralt. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Leap day, giant viruses, and gene-editing appeared first on OUPblog.

March 6, 2016

Latin: the Renaissance’s world language

George: Just what coop or cave do you come to us from? – Livinus: Why ask such a question? – George: Because you’re ill fed. Because you’re so thin you’re transparent; you creak from dryness. Where’ve you been? – Livinus: The Collège de Montaigu. – George: Then you come to us full of learning. – Livinus: Oh no – full of lice. – George: Fine company you bring with you! – Livinus: Yes indeed; it’s not safe nowadays to travel without company.

One student meets another. They talk. They banter. All perfectly familiar to us, it would seem—except that the original of this conversation is in Latin. We find it in Erasmus’ Colloquies, first published in 1518 and one of the best-selling books of its time. Livinus and George’s fictional dialogue could easily have been a real-life exchange; as a tutor himself Erasmus intended his Colloquies to provide models for everyday conversation in Latin, and Latin was the language of instruction in schools and universities at the time. Pupils were encouraged to speak Latin among themselves, even outside the classroom. Moreover, when students from different countries met in international academic centres like Paris (where our Livinus was accommodated in the Collège de Montaigu), Latin was the lingua franca of choice, very much like English’s status in many institutions of learning across the world today. 400 years ago, to reach as wide a readership as possible, we would be writing this piece in Latin, and to our reader that choice would not seem an élitist affectation, but completely normal. All of this had profound consequences for the composition of literature.

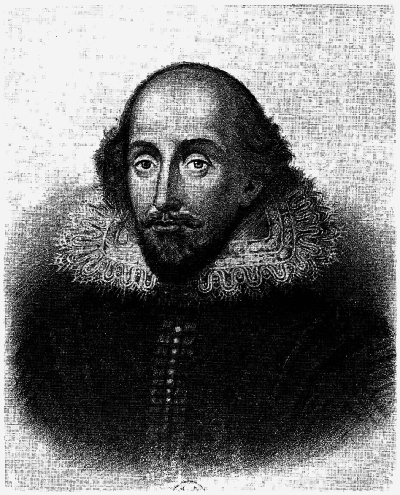

In As You Like It (c. 1599), Shakespeare includes “the whining school-boy with his satchel” as the second of his seven ages of humanity; we tend to forget that for Shakespeare—as for Rabelais, Lope de Vega, Milton, Camões, Cervantes, Kepler, Newton, and all other educated boys in early modern Europe—“school” meant immersion in Latin. Many writers went on to abandon that schoolroom language along with their satchels, opting instead to articulate their ideas in their native tongues, but just as many continued to write in Latin throughout their lives. To name just two seventeenth-century English examples, the best-known poet and the best-known scientist, Milton and Newton, always worked bilingually. At the start of the previous century, outliers like Machiavelli had sparked controversy because of their decision to write their political works in the vernacular, while a few decades later poets such as Ronsard agonised over the choice of Latin versus French. The point is that writers during this period always had to contend with Latin; they were immersed and tested in it from boyhood, and if they rejected it for the vernacular, they often felt compelled to justify that preference to their contemporaries.

“…[W]e tend to forget that for Shakespeare – as for Rabelais, Lope de Vega, Milton, Camões, Cervantes, Kepler, Newton, and all other educated boys in early modern Europe – ‘school’ meant immersion in Latin.” William Shakespeare. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“…[W]e tend to forget that for Shakespeare – as for Rabelais, Lope de Vega, Milton, Camões, Cervantes, Kepler, Newton, and all other educated boys in early modern Europe – ‘school’ meant immersion in Latin.” William Shakespeare. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Latin, then, was a ubiquitous and commonplace language in the Renaissance, widely spoken, read, and written across Europe and beyond. If the defining characteristics of what has variously been called a “world language” and a “universal language” are its number of non-native speakers and its international circulation, by the time Erasmus was writing his Colloquies and Shakespeare his comedies Latin had been a paradigmatic world language for well over a millennium. Through the army and administrative framework of the Roman Empire, Latin spread throughout Europe, prompting Pliny the Elder in his Natural History to praise patriotically Rome’s ability to “draw together the discordant and wild languages of so many peoples” into “a shared form of speech.” After the fall of the Empire, newly harnessed to the momentum of the Christian faith, Latin continued to be happily or at least pragmatically adopted by Europe’s peoples as a cultural force until the end of the early modern period. Arguably, it reached its greatest moment of self-conscious refinement between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries. Scholars have often tended to focus on the rise of vernacular languages and literatures during the Renaissance, but this habit unduly eclipses the continuing, vital role of Latin as the only true international language of early modern Europe.

So while Latin has always been a linguistic and cultural force in the history of the West, its spread in the early modern period reached an all-time high thanks to new educational dynamics and the invention of moveable type around 1450. Statistics forcefully demonstrate the language’s power and growth; about 95% of all extant Latin texts date from the Renaissance onwards, while classical antiquity’s share only adds up to about 0.01%. Certainly a substantial majority of books printed in sixteenth-century Europe were in Latin, and the larger part of them were not just new editions of ancient works but original compositions. Works like Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), which introduced a whole new genre of imaginative political thinking, or Nicolaus Copernicus’ De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543), which established the heliocentric system, attest to the creativity and impact of what is now often conveniently called “Neo-Latin.” Neo-Latin shaped European history and extended beyond that single continent both westwards and eastwards, as governments explored, colonized, and plundered the Americas, Asia, and elsewhere. With this geographical extension, due mostly—but not only—to Jesuit missions, Latin reached a global dimension that hardly any other lingua franca ever had. Could we perhaps call it the first world language in the proper sense?

However this may be, Latin’s reach and significance as an active language in the early modern period has been at the centre of a number of recent studies and this debate is likely to continue. Peter Burke characterizes Latin as “a language in search of a community” and suggests that the search ultimately succeeded because of its cohesive value for the Catholic church and the Republic of Letters. Benedict Anderson sees Latin’s “fall” from the mid-seventeenth century onwards as accelerated by what he calls “print-capitalism” and as part of a larger process of nation-building which “fragmented, pluralized, and territorialized” communities formerly “integrated by old sacred languages.” Minae Mizumura considers how adoption of a “universal language” like English in the modern world can erode local and national consciousness and literary writing, noting Latin’s earlier “crucial role in Europe’s bid to become the world’s dominant power,” its importance for the growth of the natural sciences and humanities, and then the move of previously Latin-writing “seekers of knowledge” towards the national vernaculars. And as Jürgen Leonhardt argues in his recent Latin: Story of a World Language, the discussion about the global role of English in today’s world can make us more sensitive to the role of Latin in the early modern period. This could also be an opportunity for a broader appreciation of Neo-Latin and its own remarkable story.

Image Credit: “Latin letters” by Tfioreze. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Latin: the Renaissance’s world language appeared first on OUPblog.

The business of politics

Political races in the United States rely heavily on highly paid political consultants who carefully curate the images of politicians, advise candidates on polling and analytics, and shape voters’ perceptions through marketing and advertising techniques. More than half of the $6 billion spent in the 2012 election went to consultants who controlled virtually every aspect of the campaigns, from polling, fundraising, and media to more novel techniques of social media and micro-targeting. These consultants play a central role in political campaigns-determining not only how the public sees politicians, but also how politicians see the public.

Sanskruta Chakravarthy, a student of Adam Sheingate’s at Johns Hopkins University, created a beautiful infographic to illustrate the impact of political consultants on campaign expenditures in the 2012 election.

Featured Image Credit: “USA Industry” by AK Rockefeller. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The business of politics appeared first on OUPblog.

Shake your chains: politics, poetry, and protest

This year, 21 March marks not just the beginning of the Political Studies Association’s 2016 Annual Conference in Brighton but also World Poetry Day. Formally ratified by UNESCO in 1999 but with antecedents that date back to the middle of the twentieth century, World Poetry Day’s aim is to promote the reading, writing, publishing and teaching of poetry throughout the world and, as the UNESCO session declaring the day says, to ‘give fresh recognition and impetus to national, regional and international poetry movements. But is there a link between poetry and politics that deserves fresh recognition?

One of Sir Bernard Crick’s last pieces of published scholarship was a chapter in the Oxford Handbook of British Politics entitled ‘Politics and the Novel’. The argument was simple and clear: novels provide a powerful mode of political expression due to the manner in which they allow writers to re-imagine a different world, to suggest alternative ways of living or highlight the risks of taking democracy for granted. But what arguments might a similar chapter on ‘Politics and Poetry’ take? How would a scholar even begin to unravel, let alone prove, the existence of relationships and influences that trespass across traditional disciplinary and professional boundaries? (Why do I persist in setting myself such challenging questions?)

The only thought that comes to my mind as a starting point for engaging with these questions is Mario Cuomo’s powerful slogan that all politicians “campaign in poetry, but govern in prose” and I can understand the contrast between the emotive and free-floating nature of speechmaking compared to the Procrustean reality of actually trying to govern and “the slow boring through hard wood” that Weber emphasized with almost poetical form. But I’m scratching the surface of something far deeper…and then I see the link that allows me to drill-down into not only the “poetry/prose” distinction that Cuomo highlights but also in relation to Crick’s work on the power of the novel. This drilling-down releases two veins of thought. The first can only be explained through the use of a section of David Orr’s wonderful essay “The Politics of Poetry” (2008) in which he writes,

Shortly before Ohio’s Democratic primary, Tom Buffenbarger, the head of the machinists’ union and a support of Hillary Clinton, took to the stage at a Clinton rally in Youngstown to lay the wood to Barack Obama. ‘Give me a break!’ snarled Buffenbarger, ‘I’ve got news for all the latte-drinking, Prius-driving, Birkenstock-wearing, trust fund babies crowding in to hear him speak! This guy won’t last a round against the Republican attack machine’. And then the union rep delivered his coup de grace: ‘He’s a poet, not a fighter!’

Ouch

The implication was Cuomo-esque in the sense that Obama was being framed as someone who could play the game of winning votes but did not have the mettle for the worldly art of politics. Of course, he did win and he has demonstrated an impressive capacity for “playing the game” while maintaining a relatively clear moral position and vision. In many ways, the great skill of Obama rests not just with his clarity of thought but with his oratory skills: he connects with large sections of “the public” within and beyond the United States. But does this connection have anything to do with poetry?

I think it does…but not in the sense of “being a poet” in the Big “P” sense of the term (learned, professional, somewhat aloof, etc.) but in a small “p” sense that is actually far easier to comprehend in relation to the role and skills of professional politicians. “The Presidency is not merely an administrative office. That’s the least of it,” Franklin D Roosevelt once argued. “It is more than an engineering job, efficient or inefficient. It is pre-eminently a place of moral leadership. All our great presidents were leaders of thought at times when certain historic ideas in the life of the nation had to be clarified.” Roosevelt captures not only the sense of political leaders acting as lightning rods for public frustration, or figureheads to rally around in times of crisis; but someone who claims to offer direction, a set of imagined relationships, and certainty in an era of increasing risk. Roosevelt therefore points towards a deeper emotive bond between the politician and the public. And it was exactly this emotive, affecting relationship that Percy Bysshe Shelley pinpointed when he wrote,

Poets are the hierophants of an unapprehended inspiration; the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present; the words which express what they understand not […] Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.

But if poetry can act as a form of expression in the relationship between the governors and the governed, then it must also act as a tool for the masses and not just the elites. And it does, and has and continues to fulfill this role. Poetry as a mechanism of protest, as a call to arms, has a distinguished history that has in recent years evolved and exploded into a rich repertoire of online and offline forms that broaden into the realm of the spoken word, hip-hip, rap and protest music. Three reference points provide just the historical hop-skip-and jump that we need to provide a sense of that evolution. The first brings us back to Shelley, a radical in his poetry and his political and social views, whose The Masque of Anarchy (1819) – “Shake your chains to earth like dew / Which in sleep had fallen on you / Ye are many – they are few” provides just a taste of the thrust and power of his verse.

If Shelley provides the “hop” then Gil Scott-Heron provides the “skip” with his muscular and powerful approach to political poetry as both an interpretation of and call to protest. His satirical spoken word poetry “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” (1970) took its title from a popular slogan among the 1960s Black Power movements in the United States and its lyrics either mention or allude to several television series, advertising slogans and icons of entertainment and news coverage that serve as examples of what “the revolution will not” be or do.

You will not be able to stay home, brother

You will not be able to plug in, turn on and cop out

You will not be able to lose yourself on skag

And skip out for beer during commercials

Because the revolution will not be televised

Jumping forward to today the work of Scroobius Pip continues this critique of ephemera and commercialization in works such as “Thou Shalt Always Kill” (recorded with Dan Le Sac, 2007). The central message, as with Gil Scott-Heron’s work, is that young people should always think for themselves rather than getting caught-up in the shallow market-led trends of modern culture.

Thou shalt not judge a book by its cover.

Thou shalt not judge Lethal Weapon by Danny Glover.

Thou shalt not buy Coca-Cola products.

Thou shalt not buy Nestlé products…..

Thou shalt not put musicians and recording artists

on ridiculous pedestals no matter how great they are or were.

The style and pace may be far removed from traditional poetical forms and, as such, sits within the broader “spoken word” genre of political expression but the emotive power and the political argument remain clear. It is a protest. It is a call to arms. It is not, however, a call to violence. “Thou shalt think for yourselves. And thou shalt always… Thou shalt always kill!” may provide the final lines of the verse but “killing” in this sense is refers to vernacular street slang for “excellence.”

“To kill” in the modern vernacular sense provides us with a valuable lens on the link between poetry, politics and protest that this article has attempted to tentatively explore. To challenge convention; to think for yourself; to dig deep; to refuse to follow the crowd; to think the thoughts that society does not allow. The poetry itself, in the sense of the specific written prose, is also arguably less important than the socio-political context in which individuals are free to write, which is why poetry, and literature in all its genres, often has most impact in those authoritarian regimes that seek to repress not just movement but thought. Taking this further – and I must now warn the reader that I am writing well beyond my intellectual comfort zone – one might argue that the role of a political leader is not just about the use of language and oratory or being a small “p” poet as a form of statecraft but of actually daring to facilitate an environment in which poetry can flourish. Speaking at Amherst College in 1963, John F. Kennedy made an incredibly perceptive statement, “Society must set the artist free…to follow his vision wherever it takes him.” James Joyce uses his literary alter ego to make a similar point in A Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man (1916) “Where the soul of a man is born there are nets flung at it to hold it back from flight. You talk of nationality, language, religion. I shall try to fly by those nets.”

It is for exactly this reason that politicians have often felt threatened by poetry and why dominant political orthodoxies have often insisted that art should remain subservient to politics. Could there be any better reason for supporting World Poetry Day on 21 March 2016? Fly by those nets, shake your chains.

Image credit: “Percy Bysshe Shelley” by Alfred Clint, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Shake your chains: politics, poetry, and protest appeared first on OUPblog.

Militias and citizenship: the eighteenth century and today

Citizenship is central to our political discourse in Britain today. From John Major’s ‘Citizen’s Charter’ to New Labour’s introduction of citizenship classes for schoolchildren – and citizenship tests for immigrants – it is a preoccupation that spans the political spectrum. Citizenship suggests membership of the national community, membership that comes with both rights and responsibilities. In David Cameron’s ‘big society’, for example, community-minded citizens are expected to rush in to fill the gaps left by the retreat of the state.

As a historian, I have long been interested in the theme of citizenship. My work has tried to think about the importance of masculinity in the spheres of politics and war – areas where men were so ubiquitous that their role was (and is) taken for granted. Citizenship is about the role of the individual in the community, and how that individual is defined in social terms, so it is a very good ‘way in’ to these fields for historians of gender.

I first got into the militia debates of the Seven Years War when I was studying the early days of British radical politics in the 1760s. It struck me that the militia enthusiasts talked about citizenship in much the same way as radical politicians like John Wilkes. This was an opportunity for patriotic, propertied men to serve their country and defend what was dear to them as husbands, fathers, and householders. Indeed, the militia debates occurred a decade before Wilkes started using these arguments at his famous elections for Middlesex, and used language that was remarkably inclusive in social (if not gender) terms: national defence was a way for all men to earn their citizenship.

Image credit: John Wilkes statue by Martin Addison. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: John Wilkes statue by Martin Addison. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Martial capability was therefore a specifically masculine way of thinking about citizenship. It had long been thus. Roman men earned their citizenship through military service and classical political theory located the republic’s power in its citizenry of male householders. Machiavelli revived these ideas in the renaissance, and during the English Civil War James Harrington argued that a citizenry of armed, substantial householders could never be overawed by a despot. Entrusting national defence to a militia was therefore politically safer than a standing army that could be turned against the people. The citizenry have to maintain their masculine martial virtues if their liberties are to be protected against internal and external threats.

Georgians famously revered the classics and discussions about the militia in the eighteenth century were conducted in recognisably classical terms. But this equation of citizenship with martial masculinity took on a new significance in the period of the Enlightenment. At a time when the bases of the political and social order were being rethought, the exclusion of women – and certain sorts of men – from political power was being reasserted and justified in new ways.

When I got interested in the Georgian militia, then, I was preoccupied with the theme of political citizenship. It may seem odd that I wasn’t a military historian, but then relatively few historians of the English militia are. Possibly because it never faced the large-scale invasion that it was created to repel, it holds relatively little interest for operational military historians. Most historians who have studied the militia in detail (and there aren’t many) were interested in the politics or the social history of the institution.

This relationship between the militia and citizenship has puzzled the militia’s historians. The usual line of argument is that the militia ideal bore no relation to reality: once the Militia Act passed into law in 1757, it became a quasi-conscript force subject to martial law, an adjunct to the regular army and a prop of the establishment.

As a cultural historian, though, I’m not so sure that ideal and reality can be separated quite so easily. By focusing both on representations of the militia and men’s experience of it in practice, I have tried to make a qualified case for militia service as a form of citizenship. The heady masculine rhetoric of the 1750s militia reformers may not have been reflected in the daily realities of service. But the sense of serving the nation, pride in wearing a county uniform, participation in national ritual and postings around the UK fostered feelings of national belonging and individual agency. It certainly broadened the political horizons of many men who were not citizens in an electoral sense.

This relatively benign reading of a militia movement may seem incongruous. Nowadays we tend to associate ‘militias’ with political extremism, be they Islamist militias in Africa and the Middle East, or the militia movement that is currently on the rise in Obama’s America. The rightwing ‘militia’ that recently occupied the wildlife sanctuary in Oregon emphasised their patriotism, their liberties and their opposition to central government – arguments that would be very familiar to Georgian Britons.

Certainly there is much about the Georgian militia that would be out of place in Britain today: the masculinism and xenophobia of its rhetoric, or the argument that civilians require arms to protect themselves against overmighty governments and foreign invasion. On the other hand, the Georgian militia enthusiasts’ ideal of citizenship had much to recommend it. They argued that people should be vigilant, active, community-minded, public spirited and wary of their governors – ideals that are still relevant to citizenship today.

Headline image: Cromwell in the Battle of Naseby in 1645, by Charles Landseer (1799-1879) by Hajotthu. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Militias and citizenship: the eighteenth century and today appeared first on OUPblog.

Early modern drama and the New World

The so-called golden age of Shakespeare coincided with the so-called golden age of exploration. Yet despite the far-reaching impact of the expanding globe, no play is set in the Americas, few plays treat colonization as central to the plot, and only a handful feature Native American characters (most of whom are Europeans in disguise). Shakespeare’s The Tempest draws on transatlantic travel narratives, it is true, yet we must remember that Caliban’s island is located in the Mediterranean, if it is really located anywhere. Allusions to the Americas abound, to specific places like Virginia or to a vaguer “Indies,” but overall early modern drama seems less interested in the western Atlantic than in, say, the North African littoral, Ireland, or the East Indies—a reflection perhaps of England’s belated presence in the Americas. (It is likely that the anonymous The New World’s Tragedy (1595), Day, Haughton, and Smith’s The Conquest of the West Indies (1601), and the anonymous The Plantation of Virginia (1623) all had New World settings, but no texts of these plays survive.)

The impact of the New World on early modern drama, then, seems muted from our perspective. But that does not mean that there was no interest, nor does it mean that audiences were not exposed to New World subject matter. Indeed, as we’ll see, promoters of trade and settlement (particularly in relation to Virginia) were all too wary of the influence of early modern drama in shaping public opinion.

The travel play—a popular dramatic genre in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries—frequently revolved around oceanic voyaging to real and sometimes imaginary places. Even though the New World largely remains off the travel play’s world map, increased occidental voyaging likely contributed to the success of this genre. Fletcher and Massinger’s The Sea Voyage is a rare instance of a play that draws explicitly on the Atlantic world, and even then, like The Tempest, its spatial coordinates are by-and-large obscured.

Christoper Columbus arrives in America, L. Prang & Co., Boston (1893). Library of Congress. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Christoper Columbus arrives in America, L. Prang & Co., Boston (1893). Library of Congress. Public Domain via Wikimedia CommonsRather than travel plays (or romances), London City Comedy seems to have been the genre through which early modern English audiences accumulated knowledge of New World matters. For playwrights, the New World could stand as an analogue for the city, which—because of rapid growth and increase in foreign trade—had become, to all intents and purposes, a new world in and of itself. No wonder then that a number of plays set in London draw on New World reference points to emphasize the strangeness of the city. Trinculo the Jester, stuck on a strange island in The Tempest, recalls the behaviour of the English who would rather give “ten doit to see a dead Indian” than one “to relieve a lame beggar.” Trinculo’s “Indian” is presumably from the Americas, given the prominence of Native American visitors to London at the time—something to which Shakespeare and John Fletcher allude in their collaboration Henry VIII or All is True, with its reference to the “strange Indian with the great tool.”

If travel plays celebrate encounters with the foreign and the strange in far-flung places, London city comedies hold up characters associated with the New World as strange objects of mockery. Bartholomew Cokes foolishly ventures to the Virginia-like Fair in Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair, while Justice Overdo grandiosely compares his “labours” and “discoveries” to those of “Columbus, Magellan, or our countryman Drake,” only to end up in the stocks. “Tobacconists,” inveterate smokers, are rendered impotent by their addictions; in Edward Sharpham’s The Fleer Petoune, named after a kind of tobacco, is so obsessed with “divine smoke” that he lives far beyond his means, spending all he has on “the Indian plant.” The New World is associated with bad investment, attractive only to desperados–characters like the adventurers of Jonson, Chapman, and Marston’s Eastwward Ho!, who think that they can flee their creditors by heading to Virginia.

The satirizing of adventurers and settlers caught the attention of promoters of colonialism. One member of the Virginia Company complained about “the licentious vaine of stage poets” badmouthing the nascent colony, while another accused the players of being enemies on a par with the Devil and the Catholic Church. Such invective leveled at the playing companies seems disproportionate, given that relatively few plays engage with Virginian subject matter for any length of time, and likely reflects the dire state of English transatlantic settlement and enterprise at the time. The Virginia colony, established in 1607, frequently seemed on the verge of dissipation, while the Virginia Company was permanently short of funds. It was only in the 1620s that the colony took on a degree of permanence.

But even though the Virginia Company was sensitive to how its mission was represented, when we piece together the various moments of mockery and satire across a wide range of plays, and consider how the early modern playhouse functioned as a news-source (or rumour mill), it certainly seems that early modern drama hit a nerve. Indeed, we might go so far as to say that, for supporters of transatlantic trade and settlement, drama was seen to be, as it were, anti-American.

The post Early modern drama and the New World appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the month: David Hume

This March, the OUP Philosophy team honours David Hume (May 7, 1711 – August 25, 1776) as their Philosopher of the Month. Born in Edinburgh, Hume is considered a founding figure of empiricism and the most significant philosopher of the Scottish Enlightenment. With its strong critique of contemporary metaphysics, Hume’s Treatise of Human Nature (1739–40) cleared the way for a genuinely empirical account of human understanding.

Hume belonged to a landed family of modest means, with connections to the law. Spending his formative years in the Scottish Borders at his family estate, Hume probably attended private school before entering Edinburgh University at the age of ten in 1721. There Hume would have attended courses in Latin and Greek, before proceeding to logic and metaphysics in his third year, and natural philosophy in the fourth. His philosophy professors were Colin Drummond and Robert Steuart.

Under pressure to adopt a legal career, Hume read widely in moral philosophy and history. Hume lived with his family until finding temporary employment with a Bristol merchant in 1734. This did not suit him, and Hume travelled to France, where he learned to speak a language he previously only read. He returned to London in 1737, and after 1739 Hume moved back to Scotland. Shortly after finishing college, Hume began serious study of Greco-Roman philosophy and literature.

Books I and II of Hume’s Treatise of Human Nature were published in early in 1739, followed the next year by Book III. Despite poor initial sales, the Treatise is considered the greatest study in skeptical philosophy in the English language. Subsequent scholarship has failed to agree on the complexities of Hume’s skepticism, and on whether it was more than a phase in reaching his full philosophical system. The “human nature” of Hume’s title refers to the human mind. Culminating in a theory of action, Hume’s Treatise broadens its investigation from the private to the public sphere, crossing into socio-behavioural theory.

Hume intended to follow the Treatise with at least two further projects, neither of which came to fruition as planned. Two volumes of Essays, Moral and Political (1741–1742), contain some exercises in political science based in Hume’s analysis of human nature—particularly the operation of passion in the motivation of governors and governed. Further philosophical work by Hume includes Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748), Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals (1752), Political Discourses (1752), and The Natural History of Religion (1757).

A long-standing interest in the field led to Hume’s massive History of Great Britain. On display in the six volumes Hume published between 1754 and 1762 are his narrative brilliance and skill in organizing complex data into a comprehensive system. Primarily structured around the history of the monarchy, Hume’s volumes also encompass social, economic, and cultural histories.

Retiring to Edinburgh in the summer of 1769, Hume developed a detached view of the political follies of the nation and revised his writings for posterity. At the height of his literary reputation, Hume died on August 25, 1776. Today, Hume is perhaps best remembered for his “constant conjunction” account of causality, and the associated problem of induction. Hume is also remembered for his rejection of the “self-interest” view of human nature and morality, and for attempting to lay the foundations for an empirical science of human nature.

Featured image credit: David Hume, depiction by Allan Ramsay. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Philosopher of the month: David Hume appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers