Oxford University Press's Blog, page 543

February 28, 2016

Why we do what we do

You walked out the door this morning. Why did you do it? Perhaps because you wanted to stretch your legs. Perhaps because you wanted to feel the fresh air on your face and the wind blowing through your hair.

Is that it?

Not quite. I bet you also walked out the door this morning because the phone didn’t ring a second earlier. And because you didn’t see a huge storm approaching. I bet you also walked out the door this morning because you didn’t promise a friend that you would meet him at home. And because you didn’t have to help your spouse with some household chores. And, more generally, because you had no moral obligation that required staying at home. (The list doesn’t end there. In fact, it may continue on indefinitely.)

Now, imagine your cat walked out the door this morning too. Why did he do it? The list of reasons is more limited in his case. In particular, it doesn’t make reference to any moral reasons. Cats don’t listen to moral reasons!

Photo of a cat (probably not being morally responsible) by rihaij. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Photo of a cat (probably not being morally responsible) by rihaij. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Humans can be morally responsible for their actions. Cats can be awesome in other ways, but we don’t think that they bear moral responsibility for anything. When we blame them for something, we don’t really mean to! (Or we shouldn’t mean to: they are not morally responsible agents.)

Why is that? Why is it okay to hold humans, but not cats, responsible for what they do? Arguably, it’s because human acts can be free in a sense that feline acts cannot. We have free will, and cats don’t (in a full-blown sense of having free will, which is required to be morally responsible for things).

But what does having free will consist in?

Perhaps you thought that it consists in not having causes, or in not being subject to causal influences that determine what we do. However, the example of the morning walk suggests an alternative picture that is more plausible, on reflection.

According to this alternative picture, acting freely doesn’t consist in being free of causal influences. It doesn’t consist in being uncaused. Quite on the contrary, acting freely consists in having many and complex causes. Most of those causes are not immediately apparent to us (unless we are incredibly self-conscious persons!). Some of them concern moral reasons.

Cats don’t listen to moral reasons!

Also, many of those causes are not positive reasons, but lacks of reasons. When we do something freely, we do it because we see good reasons to do it, but also, at least typically, because we don’t see sufficiently strong reasons to refrain from doing it. The lack of reasons to refrain is an important part of the explanation of why we act, and of why we act freely.

Although the whole range of causes of our behaviour may not be immediately obvious to us, the causes are still there, shaping our behaviour. We see this in simple cases like the morning walk. Even in those very simple cases, the list of causes is long and rich, and it contains reasons and lacks of reasons, some of which are moral in nature.

Like the happenings in the world around us, our acts have multiple and complex causes. In the world’s complexity lies its beauty. Similarly, in the complexity of the causal sources of our acts lies the beauty of our free will.

Featured image credit: Footprints in the sand, by Unsplash. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Why we do what we do appeared first on OUPblog.

February 27, 2016

Political profanity and crude creativity on the campaign trail

In the United States, thoughts are turning to the start of the primary season, when votes are cast to choose each party’s presidential nominee. It’s a complicated and sometimes very long process, beginning in Iowa and winding all the way to the conventions in the summer, and every time it gets going, there are certain buzzwords that seem to find their way into the American popular consciousness. Flip-flop first became widely used in 2004, and could anyone forget hanging chads back in 2000? Not to mention the “hopey changey stuff” mentioned by Barack Obama and derided by Sarah Palin in 2008.

Refudiating real words

In fact, Ms. Palin has made her return for this election to endorse one especially colourful candidate who’s been notable for the use of a different, more vernacular—and some say vulgar—language on the campaign trail. Speaking up in favour of Donald Trump, she managed to come up with at least one word that’s also not made it into the dictionary thus far: squirmish, in the context of continuing battles in the Middle East. Like George W. Bush, whom Saturday Night Live successfully portrayed as using words such as strategery, Ms. Palin has been known for her idiosyncratic use of language in the past. Perhaps most famously in 2010, she tweeted the word refudiate (a portmanteau of refute and repudiate), which was Oxford Dictionaries’ Word of the Year a few months later.

But the man she’s endorsing has managed to come up with a few new words and phrases of his own—including one that sounds like “bigly,” though some say he means “big league.” Mr. Trump has used it repeatedly as a means of emphasis in stump speeches (stump used in relation to political campaigning, referring to the use of a tree stump, from which an orator would speak). Instances include phrases such as “Iran is taking over Iraq bigly,” or referencing Fox News talking “bigly” about immigration. The property tycoon’s New York-accented pronunciation has also catapulted the word yuge (his way of saying huge) into the media election lexicon, with pundits writing about Trump’s “yuge” crowd or “yuge” lead in the polls. Brooklyn-born Bernie Sanders, a candidate for the Democratic nomination, pronounces the word the same way (perhaps one of the only things the two men have in common).

Hillary got what?

But it’s not just Trump’s pronunciation that’s hit the headlines—it’s also his use of controversial words and phrases, including anchor baby, used to refer to a child born in America to parents who aren’t citizens. Fellow Republican candidate Jeb Bush was mired in controversy when he used the term last August, but Mr. Trump uses it unapologetically, even in the description of another candidate, Ted Cruz.

And when it came to describing Democratic presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton’s performance in the 2008 presidential race, Donald Trump used a word many Americans also considered offensive (as well as unusual), saying the former First Lady had gotten schlonged. Some interpreted the term as turning the vulgar, Yiddish-derived noun schlong (penis) into a verb. Some felt the word wasn’t worthy of a man seeking higher office. And some speculated that he might have meant something else, but whatever the intention, the term’s likely to go down in the annals of American political campaign history.

Ass-kickings and other profanities

The use of familiar, vulgar terms has been something of a theme of Mr. Trump’s speeches, from his frequent use of the word loser to describe his opponents or those with whom he disagrees, to phrases such as “you bet your ass I would,” when asked if he would approve waterboarding terror suspects. Attendees at his rallies can buy badges calling for America to “bomb the shit out of ISIS,” while Sarah Palin said she was endorsing Trump because he’d be a President who would “kick ISIS ass.”

This kind of slang has been used by other candidates too; former Florida governor Jeb Bush has said, “We’re Americans, damn it!” at a fundraiser, and Kentucky Senator Rand Paul accused those defending government surveillance of talking “bullshit.” Ben Carson, during a nationally televised Republican debate, derided government subsidies as a “bunch of crap.” And even Bernie Sanders, also in a televised debate, said that the American people were tired of hearing about Hillary Clinton’s “damn emails.” But Mr. Trump seems to be in the lead when it comes to his use of familiar slang, especially to those who’ve crossed him, who’ve been called, among other things, jerks, clowns, and morons.

Of course, British politicians aren’t above using this kind of language; see, for example, Ed Miliband’s recent “hell yeah” when asked by Jeremy Paxman if he were tough enough to take on the role of Prime Minister. David Cameron had to apologize after saying “too many twits might make a twat” during a 2009 radio interview. And they too can be muddled in their use of words; former Scottish Labour leader Jim Murphy was widely ridiculed for pronouncing fundamentally as “fundilymundily” at the Leaders’ Debate in Edinburgh in 2015.

But it seems it’s American politics, with its wide range of candidates and relative informality, that’s continually generating more creative, vibrant and, yes, sometimes puzzling or shocking language. And there’s a long time to go until 8 November, so we’re likely to see a great deal more in the meantime.

A version of this blog post originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Image Credit: “Donald Trump” by Gage Skidmore. CC BY SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Political profanity and crude creativity on the campaign trail appeared first on OUPblog.

How much do you know about Shakespeare’s world? [quiz]

Whether in Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and beyond — or in various unknown, lost, or mythological places — Early Modern actors treaded stage boards that could be familiar or unfamiliar ground. Shakespeare made some creative choices in the settings of his plays, often reaching across vast distances, time, and history. The great cities of Troy and Tyre no longer existed, and the Britain of Cymbeline and King Lear was long gone. Most of his London audience had never visited Italy, yet he set plays in Venice, Verona, Mantua, and Messina. With these wide ranging locations, he frequently united characters from different backgrounds, comparing their cultures, languages, and practices. How well do you know the numerous places to which Shakespeare invites his readers? Can you name the home countries of some of his most famous characters?

Do you have any Shakespearean geographical brain teasers to add? Let us know in the comments below.

Featured Image: Nova totius terrarum orbis geographica ac hydrographica tabula (1606). Guiljelmo Blaeuw. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post How much do you know about Shakespeare’s world? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know Plato? [quiz]

The OUP Philosophy team have selected Plato (c. 429–c. 347 BC) as their February Philosopher of the Month. After his death in 347 BC, educators at the Academy continued teaching Plato’s works into the Roman era. Today he is perhaps the most widely studied philosopher of all time. The best known of all the ancient Greek philosophers, Plato laid the groundwork for Western philosophy and Christian theology. But how much do you know about his life?

Take our quiz to see how much you know about Plato.

Quiz image: The School of Athens, by Raphael (1509–1510). Public domain by Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: Athens Temple, by santa2. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post How well do you know Plato? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

February 26, 2016

Constructing race in world history

Racism is alive and kicking. We see it in the news; we see it in our lives. And yet our modern concept (and practice) that involves notions of “race”—on which racism rests—is a recent invention. While people and their societies have long distinguished among themselves—Romans distinguished between “citizens” and “barbarians,” and the Zuni spoke of “winter” and “summer” people—the concept of innate superiority or inferiority among people, as opposed to environmentally or culturally-acquired characteristics, is only a few centuries old.

Neither genetically-based nor a biological category but a function of power (those in power disproportionately determine standards of beauty, morality, comportment, and intellect), race, like all other identities, has been a constructed and shifting term in world history.

Ancient and other pre-modern societies took difference in tribal affiliation, place of origin, language, class, religion, and foods eaten, as distinguishing factors among people: Egyptians during the New Kingdom depict four “races” in the Book of Gates, but presented these as geographic in origin, with each figure holding similar status; in China, distinctions were made between “raw” and “cooked” peoples; meanwhile, Aristotle in Politics argues that colder climates produced socially and politically inferior kinds of people in comparison to those who lived in temperate climates, such as his own Aegean. Centuries later, Muslims divided people into “believers” (People of the Book) and “nonbelievers” (kaffir), the latter implicitly viewed as morally inferior (now used as a racial slur in southeastern Africa); and in the Deccan, paintings from the early modern era depict dark-skinned Abyssinian elites in India being attended to by lighter-skinned pages, with class being the overriding distinction in that case.

The early modern figure Malik Ambar, an Abyssinian who was enslaved and rose to become de facto king of the Sultanate of Ahmednagar in western India, provides a vivid example of the differences in notions of race among people of African descent in the Indian Ocean world versus the Atlantic world.

“Malik Ambar” by Hashim. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Malik Ambar” by Hashim. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Born into an Oromo (Ethiopian) family in 1548, he was enslaved and then taken to Baghdad, where he was educated, later being taken to India as part of the military slave system across this part of the world. In India, he rose to power in the last decade of the sixteenth century and became Regent Minister of Ahmednagar. He ruled the sultanate for the first quarter of the seventeenth century, demonstrating that his black/African ‘race’ in this part of the world, at this particular time, did not over-determine his upward mobility. Indeed throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in western India there were dozens of Africans who were regarded as nobles—black nobles in South Asia, sometimes depicted in art as superior to non-black people, who served them.

As a social construction based on power, race has been variously practiced and institutionalized across the world. However, since the eighteenth century, race—as a set of biological, inherent characteristics—tied to color and other phenotype has become a dominant lens through which humans see and understand ourselves. While historians from the ancient world, namely, Herodotus, to those from the early modern period, as with Ibn Battuta, note phenotypic distinctions between people, such differences (and not always mentioned or discussed explicitly as “race”) did not carry the same meanings as they would come to hold in later periods of time. By and large, color was not as important for people until the modern era; for instance, the scholar Geraldine Heng demonstrates forms of racialism before the advent of a vocabulary of race in the European Middle Ages. To the extent that “race” appears in written accounts (entering English from Old French rasse and Spanish raza, itself derived from ras in Arabic meaning the head of a group) it was used as “lineage” or “ethnicity.”

Race, being a social and political construct, and therefore unstable and inconsistent across time and location, has changed repeatedly. In the United States alone racial groupings as they appear in the US Census have changed over one dozen times since 1790. Moreover, what constituted “black” in one state changed when entering another state. Along these lines, someone considered “black” in the United States might be considered “white” in Brazil. Such racial distinctions—whether in North America, South America, Africa, Western Europe, South Asia, or East Asia—have had a profound, and often limiting, if not destructive impact on people’s lives.

Among the consequences of what may be called scientific racism (including theories of monogenesis and polygenesis) has been the justification of violence against certain identifiable groups of people for economic exploitation—most notably, sub-Saharan Africans and their descendants in the Americas—centered on notions of “natural” inferiority. The “science” was expressed in medical terminology: during the nineteenth century enslaved African Americans were diagnosed, for instance, with “drapetomania,” a term coined by Virginian physician Samuel Cartwright (the “disease” of black slaves wanting to run away from captivity, with the prescription being whipping).

Race made scientific has ravaged other groups of people. On the other side of the Atlantic, and a few generations later, the racial policy in Nazi Germany of handling lebensunwertes leben (“life unworthy of life”) led to the murder of millions of Jews during the twentieth century. Related kinds of scientific racism also justified the seizure of land and the restriction of migrants into the United States. During the early twentieth century “mixed-blood” versus “full-blood” tests involved “drawing with some force the nail of the forefinger over the chest,” and seeing the mark left, to justify taking land away from Native Americans; likewise, Congressional legislation restricted immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe based on “intelligence” tests, replacing cranial measurements as proof of racialized intellectual capacities.

Therefore, despite the defeat of twentieth-century European and Japanese fascism and the dismantling of Jim Crow in the American South, despite the end of Apartheid in South Africa and the discrediting of scientific racism with the mapping of our genes, and despite multiple declarations by the international community in favor of human rights based on a widespread understanding of our single human species, purported racial differences and institutional forms of racism persist.

But if world history teaches us anything, our modern conceptions of race will themselves change as power—specifically, those who have it and how they choose to exercise it, shaping notions of difference—undoubtedly change over time.

Image Credit: “Sign for the “colored” waiting room at a bus station in Durham, North Carolina, 1940″ by Jack Delano. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Constructing race in world history appeared first on OUPblog.

The perils of salt

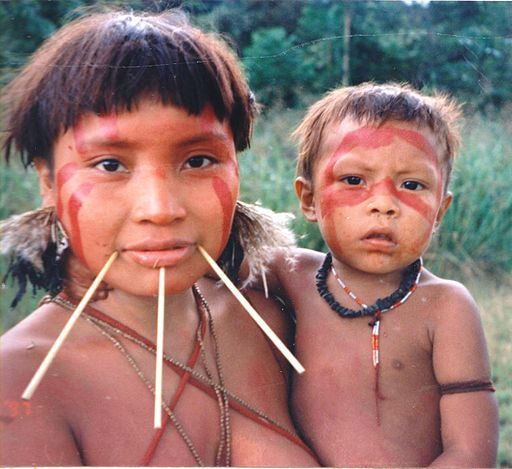

The Amazonian Yanomami people famously manage on only 50 mg (1 mmol) of sodium chloride per day, while in more developed societies, we struggle to keep our average intake below 100 times that level. It’s likely humans mostly evolved on diets more like that of the Yanomami. In response to this, the Yamomami have been found to have persistently high levels of circulating renin and aldosterone, driving maximum salt retention in the kidney.

“Yanomami woman and her child at Homoxi, Brazil, June 1997.” by Cmacauley. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Yanomami woman and her child at Homoxi, Brazil, June 1997.” by Cmacauley. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Interestingly, although the perils of salt overloading were well understood in the setting of acute renal failure in the 1940s, in chronic renal disease, many nephrologists were very late to pick up the importance of salt restriction. Addis (1949) and de Wardener (1958) identified control of salt intake as important in oedema, but both dismissed it as mostly irrelevant to chronic renal failure, even in malignant hypertension. Soon after the introduction of dialysis for end stage (as opposed to acute) renal failure, it was discovered that limitation of salt intake, and its removal by dialysis, controlled the severe hypertension that was universal in young patients with end stage renal disease in the 1960s.

There were very few other effective and tolerable treatments at that time – blood pressure charts from that era are scary. Most long term survivors from the 1960s and 1970s have experienced prolonged periods of severe hypertension. One of the earliest patients, Robin Eady, describes the transformation when he went to the world’s first chronic dialysis unit in Seattle in 1963, where Belding Scribner had determined the importance of sodium and volume balance in controlling blood pressure. That lesson has been re-learned several times since. Chronic salt and fluid overload is a major contributor to the high rate of heart failure in dialysis patients.

Table salt by Garitzko. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Table salt by Garitzko. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Observations in human populations with low salt intake and chimpanzees on similarly fruit or vegetable-rich, salt-poor diets, find lower average blood pressures and a lack of the rise of blood pressure with age that we now expect during adult life. Studies with the DASH diet and other low-salt diets show that they can lower blood pressure in hypertensive patients. These diets tend to have other potentially good things about them too.

We have also learned that lowering salt intake increases the effects of ACE inhibitors, not only on blood pressure but also on proteinuria. Other discoveries have included that most genetic causes of hypertension act through increasing sodium retention by the kidney and that mild kidney disease is much more common in the population than we previously suspected. Salt sensitivity may be an early change in kidney disease, and a large proportion of the population may be susceptible.

Should we all be eating less salt, or only those of us with high blood pressure or kidney disease? For the general population there has been an extraordinary resistance to further lowering salt intake, though there seems little to lose, and potentially a lot of gain. Some blame this on pressure and scheming from food manufacturers and the salt industry. Salt gives food longer shelf life, gives low quality food more taste, and the water sucked in increases the weight of many products (notably meat products). We seemed programmed to like salty foods, perhaps because our species lived for millennia in environments where salt was scarce and treasured, but it’s probably bad for many of us.

A version of this blog post first appeared in the History of Nephrology blog.

Featured Image: “Salt pepper macro image in studio” by Jon Sullivan. Public domain via public-domain-image.com.

The post The perils of salt appeared first on OUPblog.

On writing fantasy fiction

A version of this article originally appeared on the Manchester University Press Blog.

Why does the world need yet another book on how to write fantasy fiction? Because the public continues to show a nearly insatiable desire for more stories in this genre, and increasing numbers of aspiring authors gravitate toward writing it. As our real lives become more hectic, over-scheduled, insignificant, socially disconnected, and technologically laden, there seems to be a need among readers to reach for a place where the individual matters. Where people form bonds of friendship and camaraderie that are tangible and face-to-face around campfires in unfamiliar forests and on long, dangerous quests instead of through abstract tweets and selfies posted on Facebook pages.

Fantasy—whether traditional, epic, urban, or humorous—offers a place where the ordinary person can meet challenges and become extraordinarily heroic and significant. Or, the misfit too awkward and shy to succeed with the home crowd finds that he or she is in fact someone very special, with amazing powers that are exactly what’s needed to save the day.

Fantasy is, in fact, a comforting place—no matter how dangerous the plot may be for its characters. It gives anyone—most especially the reader—a chance to be heroic.

It drew me in originally because its detailed, unusual settings and spirit of adventure delighted my imagination. As a child, I read tomes of mythology, folklore, and ancient history in addition to Andre Norton, Edgar Allen Poe, Ray Bradbury, Alexander Dumas, and Robert Heinlein. When I grew older, I gravitated toward the historical fiction of Georgette Heyer and C. S. Forester, plus John D. MacDonald and Dorothy Sayers. All these writers, while producing divergent work, nevertheless evoke vivid locales and unusual characters. Those qualities continue to draw me to any author of any type of fiction.

While reading voraciously is vital for all writers, I think it’s important not to be too narrow. Fantasy—old and new—of course needs to be read, but do reach beyond researching magical creatures to explore other types of fiction and classical literature. Read anything that generates a better understanding of human nature and the motivating force of human emotions. I think writers of traditional fantasy need a solid grounding in history, battle strategy, politics, mythology, anthropology, and the classics, and I think writers of urban fantasy should acquaint themselves with a wide range of thrillers, mysteries, and noir films.

In addition to the lure of setting and adventure, I also love how open fantasy is to exotic, unusual characters and creatures. There are very few boundaries in this genre. Nearly anything is possible—and permissible. That sort of creative freedom is one that I revel in as an author. I think, however, that the creation of setting can be something of a tar pit for inexperienced writers.

Often, they begin by creating their own special world and populating it in their imagination. They devise elaborate histories, character backgrounds, languages, and magic systems—everything, in fact, except a plot that offers more than a random series of misadventures for the characters.

However amazing it is, the setting of any fantasy story is only one aspect. There must also be a strong, well-thought-out plot and vividly designed characters that act from understandable and sympathetic motives. Setting alone will not carry an idea very far.

The fantasy fiction formula therefore addresses the craft of writing, the nuts and bolts of how stories are first imagined and then assembled in order to give readers a wonderful time. It demonstrates the techniques that hold plots together from start to finish. It is intended to work in creative writing courses, yet it serves also as a guide for any aspiring writer. It can be followed step-by-step and chapter-by-chapter, or it can be studied randomly in any order preferred.

Beyond craft, it is intended to boost a new writer’s self-confidence, because as the techniques of fiction are mastered, imagination is freed to become more creative than ever. Not only does this book help writers to improve their stories, but it also shows them what to do when their stories veer off course.

Image credit: Fountain Pen by Jacqueline Macou, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post On writing fantasy fiction appeared first on OUPblog.

Keep your friends close… Really?

Who has never been embarrassed by a close other? Imagine you and your best friend dress up for the opera, both of you very excited about this spectacular event taking place in your home town. It is the premiere with the mayor and significant others attending. You have a perfect view on the stage and it seems a wonderful night. Silence. Nothing but the beautiful voice of the soprano. Amidst the aria a mobile close to you starts playing “Ice Ice Baby” by Vanilla Ice. Even in the front row people start turning their heads and staring into the direction of the perpetrator. It feels like hours until your friend sitting to the left of you finally manages to turn off the music. You perceive the blood in your vessels racing into your face and your heart palpitations dramatically accelerate while you try to avert your gaze from the auditory.

What happened? Although it was not your fault, your mobile, or your choice of music, you experience the flush and the unpleasantness of embarrassment escalating through your own body. This phenomenon, known as vicarious embarrassment, is an interpersonal and painful emotion experienced on behalf of others’ blunders and pratfalls. From behavioural and neuroimaging studies, we know that most human affect is rooted in the social ties with the environment that we are living in. On the neural system’s level, cortical midline structures, parts of the temporal lobe, and a region called the insula have been shown to be involved in the unpleasant experience of vicarious social pain, with vicarious embarrassment being a prominent example. The same brain regions have also been implicated when we share others’ physical pain, where they help us to feel the harm to another’s body. Likewise, our vicarious embarrassment gives us a sense of the damage to the social integrity of our fellow human beings, enabling us to relieve the devastating moments and initiate helping behaviour and reparations.

Returning to the initial anecdote, imagine whether you would have felt the same cringe if the ringing mobile of the person to your right belonged to a stranger? How does social relatedness modulate the chagrin that you experience?

To answer this question several factors have to be considered. First, the closer you are to someone the stronger your affective ties are, and thus the more intense caring for the other’s affect. Second, based on the numerous shared past experiences with your friends (e.g. sharing the grief upon the death of a friend or joint cheering in a sports event, as well as common attitudes such as rejection of racism), the mental representations of what’s going on in your friend’s mind during this unpleasant moment will be more vivid and rich as compared to an unknown other. Thus, you care more and are much better able to empathize with your friend on your left than with the stranger sitting to your right.

But what about yourself? As many humans have a strong motivation to feel connected to their social environment and accordingly are concerned about the portrayal of their social image, appreciation and positive feedback of others is important. People give feedback for one’s behaviours and attitudes through various channels. This feedback not only makes us understand the expectations of our milieu and the prevailing social norms and principals for social interactions, it also shapes the social image that one aims to portray. However, one’s close friends’ (mis)behaviours impact and threaten our social images vicariously, as friendship presumes a sharing of certain attitudes, norms, and values. In the above anecdote the circumstances are indeed severely unfavourable for your friend’s social image, but at the same time, your own social image is also being endangered. You might engage in reasoning about what the audience might think of you being a close friend to the heedless perpetrator who does not only have a questionable taste of music, but is so careless in disturbing this beautiful evening. The predicament might enhance self-related thoughts and concerns about what others might think of you.

In your brain, the precuneus in the parietal lobe, a structure known to be involved in representing others’ mental states as well as in self-related thoughts steps in. When you perceive your friend’s misbehaviour in public, the precuneus gets active as you start reflecting about yourself. This activation goes along with an increased information transfer with those areas in the cortical midline structures of the frontal lobe that mediate the vicarious embarrassment experience. It seems that the concerns about your own social image significantly contribute to your cringe-worthy moment in the opera, even though you aren’t responsible for any of what happened. Here you are at the borderline to feeling embarrassed for yourself since your related parties’ actions will reflect upon you and damage your social image. This example illustrates how much our emotional reactions depend on the social ties to our environment and are very much interpersonal in nature.

How much of these emotional experiences we are able to capture, while we try to characterize their neural foundations in the social isolation of the neuroscience laboratories, remains to be determined. There might be no need to walk into the opera with an EEG cap, or invite the audience to the MRI, but it is certainly reasonable to develop more interactive situations that make people feel directly connected to their social environment. This will help neuroscience to better understand all those factors that make us feel emotions such as vicarious embarrassment.

Featured image: Red cinema seats. (c) habrda via iStock.

The post Keep your friends close… Really? appeared first on OUPblog.

John Marshall, the lame-duck appointment to Chief Justice

As we mourn the death of Justice Antonin Scalia, we face a political controversy over whether President Barack Obama should name Scalia’s successor. As a lame-duck president, so the argument goes, Obama should leave the choice of Scalia’s successor to the winner of the 2016 presidential election. Many GOP Senators are pressing this claim, and Senator McConnell is insisting that President Obama not act, leaving the filling of the vacancy on the Court until after the winner of the 2016 election is inaugurated. President Obama is standing firm as of now, insisting that he has the constitutional responsibility to fill the vacancy on the Court, and many historians and constitutional scholars agree with him.

Many analysts of this budding constitutional brawl have listed examples of Supreme Court Justices nominated in the last year of a “lame-duck” President’s term – for example, Anthony Kennedy, whom Ronald Reagan nominated in late 1987 and was not confirmed until 1988, a presidential election year. But there is an even more telling example cutting against the current GOP position on the Scalia vacancy.

Those who argue that lame-duck presidents should not nominate justices to the Supreme Court have forgotten or ignored the most consequential appointment in the Court’s — and the nation’s — history: President John Adams’s 1801 appointment of John Marshall as the nation’s fourth Chief Justice.

The vacancy in the Chief Justiceship did not arise until after the 1800 presidential election, in which Adams lost his bid for a second term, and the disputed tie between Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr persisted into 1801. Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth, whom Adams had sent to France to negotiate a treaty to bring an end to the 1798-1800 “quasi-war” between France and the United States, sent the treaty that he had negotiated to President Adams – accompanied by his letter of resignation from the Court. Ellsworth reported that an acute attack of what he called “the gravel” – kidney stones – rendered it all but impossible for him to return home quickly via ship, and therefore, to spare the Court the burden of his absence, Ellsworth resigned.

The Ellsworth resignation complicated President Adams’s life far beyond what he could have foreseen. Adams faced a multi-level crisis in American politics — how to respond to the seeming failure of all efforts to break the deadlock in the House of Representatives between Jefferson and Burr for the presidency; how to deal with the Federalist-dominated Congress’s efforts to reform the federal judiciary, both to make it more efficient and effective and to create many new judicial posts for Federalists; and whom to choose to replace Ellsworth.

Many Federalists called on Adams to name a die-hard High Federalist, in particular advocating the nomination of Justice William Paterson, a man whom Adams distrusted as an ally of such High Federalists as Alexander Hamilton and not a friend or supporter of the President. Adams also faced suggestions that he promote another Associate Justice, William Cushing, to the chief justiceship – even though Cushing had turned down such a promotion back in 1795, after the resignation of the first Chief Justice, John Jay, to become governor of New York. Some Senators even proposed that Adams name himself the new Chief Justice, an idea that the president rejected with scorn. Adams instead chose to name Jay to his old job, and the Senate confirmed the appointment. Though Jay seemed an ideal choice, liked by both factions of Federalists and a holder of the position from 1789 to 1795, nobody had asked Jay whether he wanted to return to the Court. On receipt of the news of his nomination by the president and confirmation by the Senate, Jay wrote to Adams thanking him for the honor but frostily rejected his reappointment, on the grounds that the federal judiciary was neglected, undervalued, and frustrating for those serving on it, and declaring his absolute refusal of reappointment.

In turn vexed by the choices before him, Adams turned to Marshall, his Secretary of State. Marshall was a loyal supporter of President Adams, a Virginia Federalist, an excellent attorney, and a widely-praised diplomat; in addition, Marshall had served Adams well as Secretary of State for a year when Adams decided to nominate him for the Chief Justiceship. Adams nominated Marshall with only weeks remaining in his presidency. Though the Federalist Senate at first was reluctant to agree, preferring a High Federalist like Justice Paterson, they knew that Adams would not nominate him (something that Adams had already told Marshall with considerable heat). The Senators realized that rejecting Marshall would create a deadlock that would leave the vacancy on the Court to be filled by Thomas Jefferson or Aaron Burr. Such a prospect was too dangerous for them to accept, and they confirmed Marshall.

John Marshall served 34 years as Chief Justice and left an extraordinary mark on the nation’s history and on American constitutional development. His judicial opinions on such matters as judicial review, federalism, national supremacy, and interstate commerce form the spine of American constitutional law. Nearly two centuries later, we live in the constitutional world that John Adams and John Marshall helped to create, a world that is now the nation’s heritage. And the Marshall precedent cuts against claims by leading figures in today’s Republican Party that no lame-duck President should make an appointment to the nation’s highest court.

Featured image credit: Portrait of John Marshall by Henry Inman. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post John Marshall, the lame-duck appointment to Chief Justice appeared first on OUPblog.

February 25, 2016

A “quiet revolution” in policing

This month, we are celebrating the tenth anniversary of Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice. Apart from being an occasion for celebration too good to pass up, it is also a good opportunity to take stock of the last ten years and look to what the next ten might hold. In this piece, Peter Neyroud, General Editor of Policing, looks at past achievements and future ambitions for the journal, the field, and practitioners themselves.

Will there be any major changes for the journal?

We have already started making plans. For one thing, we have extended our word limit to 6,000 words. It is a decision that reflects how policing has changed over the last ten years. In 2005, the General Editors set the 4,000-word limit because they wanted police officers both to read the journal and write for it. This was a much tighter limit than is usual for academic journals, but the General Editors saw it as a readable length for busy practitioners, using journals like the British Medical Journal as a guide, where short articles are the norm rather than exception; they mused that 4,000 words was a length capable of being read by an officer on a meal break in the middle of the night. There is a saying in British policing that the real work is done by the “late turn van driver” and they wanted to see whether they could reach that reality.

We stayed with the shorter 4,000 word limit for ten years, while allowing a few exceptions, because we wanted to maintain our firm intent as a journal of policy and practice, rather than just another academic journal. We have also worked hard to get practitioners to publish and access the journal. It is genuinely gratifying to see so many practitioners co-authoring in our Special Edition on Australasian police leadership and management.

Moreover, our Special Edition signals that another of our intentions has borne fruit. We have called this journal international from its inception and we have worked hard to extend both its readership and its authors and reviewers across the world. The most significant recent statement of this intent has been the addition of Cynthia Lum to give us three General Editors.

How have things changed over this past decade?

Our first ten years have produced some notable articles and editions. These include New York and Los Angeles Commissioner Bill Bratton writing on performance; articles from International Criminology Prize Winners like Ron Clarke (writing with Graham Newman on policing terrorism) and David Weisburd (on legitimacy and police science); special editions on terrorism, community policing, police science, police performance, and diversity. We are also delighted to have seen many younger scholars publishing for the first time.

There is, in short, a “quiet revolution” going on in policing and policing research, which we wish to foster and develop.

What makes the journal so successful?

We are proud of achieving what many other journals struggle to do: a quick turnaround between submission and publication. We judged that we needed to be relevant. One recent reviewer commented they “worried that this belated article—that will appear in a couple of years’ time—will be dated by then and been superseded by existing publications.” They need not have worried. Our articles do not take two years to publish, because two years in policing, particularly at the moment with the pace of change, could, indeed, leave some articles looking like historical statements. We have maintained a constant intent to influence the field and the policy makers, which means that we commit to maintaining as rapid a turnaround as sound reviewing, good scholarship, and excellent editing and production can achieve.

How has the field transformed over the years?

All of the General Editors have extensive experience of the field in policing, so we know that meal breaks rarely come uninterrupted, particularly for the “late turn van driver.” However, since 2005 there has been a transformation of police education and a significant growth in police practitioners completing Masters and Research degrees. Not only have we noted an increasing number of submissions from police officers seeking to publish the findings from their own research, but also a shift in interest in research more generally in the profession.

There is, in short, a “quiet revolution” going on in policing and policing research, which we wish to foster and develop. We feel that we can best assist by encouraging a wide range of contributions from 6,000-word research articles to 2,000-word research summaries, combined with articulate commentaries and high-quality discussion pieces.

What does the future hold?

We have a plan to cover some of the most pressing topics in the field over the next few editions—domestic violence, police culture and its impact on reform and delivery, policing cybercrime, and police forensics. We are also looking to extend our international reach well beyond our core English-speaking readership and bring an increasingly worldwide perspective to our journal. Last but not least, we will publish a series of articles which will assess the “state of the field,” covering topics such as the President’s Taskforce in the twenty-first century, the development of police education, and the journals on policing.

We are ambitious. Ten years’ experience has taught us to be ambitious. However, we can see the change in the field as we look back and we hope that we have played a small part in helping it happen. We look forward to the next ten years.

Image Credit: “NYC Police Horse Around After Superbowl Parade” by Tony Fischer. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A “quiet revolution” in policing appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers