Oxford University Press's Blog, page 537

March 11, 2016

Long term effects of slave exporting in West Africa

History matters. Historical events can sometimes have consequences that last long after the events have finished. An important part of Africa’s past is its history of slave exporting. Although Africa is not unique to the trading of slaves, the magnitude of slave exporting rose to levels not previously experienced anywhere else in the world. Between 1500 and 1900, an estimated 10 million slaves were exported from West and Central Africa. To put this in perspective, the estimated population in these regions in 1700 was about 28 million people. The exports also do not include people who died either during capture, the long trek to the coast, or the journey across the Atlantic. In short, it was a significant event in Africa’s history lasting over 400 years. A significant event of this magnitude is bound to have long lasting effects.

Many researchers have tried to uncover some of these effects with some degree of success. Some find that relatively higher slave exports is inversely correlated to relatively lower GDP in more recent times. Higher slave exporting societies have also been linked to lower levels of trust, higher levels of fractionalization, and many other effects.

However, there are often challenges to uncovering the long term effects of historical events. The first, in terms of Africa, is that most of the countries for which we currently have data, were non-existent at the time. There was no such place as Nigeria in 1790. There was no such place as Zambia in 1920. Of course this is not because there were no people inhabiting those areas, but because the mode of political organization was very different. A second challenge in uncovering long lasting effects of historical events is that history never really stops. In Africa, the slave trade era was swiftly followed by the colonial era, which of course had its own long term consequences as well.

Two things can help get around these two problems. First, we can examine how things changed in the period directly after the slave trades era, and to look at places that had very similar colonial experiences. If we examine these places, then anything we uncover cannot be directly as a result of colonial experience. And if we examine changes during the colonial era, then the effects of slave trading are likely to still be prevalent.

For example, we could look at the changes that took place within Nigeria and Ghana during the colonial era, specifically with regards to educational attainment. Nigeria and Ghana are both similar countries with respect to their historical experience. They are both relatively big countries with many different ethnic groups within their boundaries. They were both heavily involved in events during the slave trade era. Finally, they both got colonized by the British and were run in a similar manner.

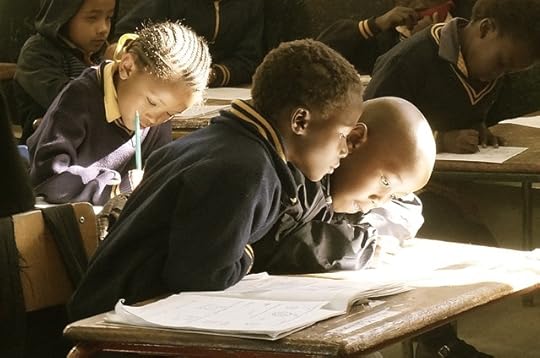

Image credit: students classroom learn by ludi. Public Domain via Pixabay.

Image credit: students classroom learn by ludi. Public Domain via Pixabay.Literacy is a useful metric for a variety of reasons. From a technical economist’s perspective, human capital is an input in the production function. Higher levels of human capital should result in higher levels of productivity and GDP. From a historical perspective, we know that the British colonial administration did not really have any education policy in the West Africa colonies. What this means is that any improvements we find can be attributed to local level activities and not top down education policy.

Literacy numbers for administrative districts in Nigeria and Ghana in the 1950s suggest that areas with a relatively high slave exporting history tended to have lower levels of literacy compared to other areas. This is after controlling for geographical, missionary, and religious influence, and other factors.

Interestingly, the effects don’t just end during the colonial era. The relationship continues to persist up to contemporary times. Local administrative level literacy rates point towards historically high slave exporting areas in Nigeria and Ghana still exhibiting relatively lower literacy rates. This confirms, as studies have highlighted, that Africa’s history of slave exporting did have long term consequences particularly on literacy.

However, these effects do not necessarily occur at the nation-state level. After all, there was no Nigeria during the slave trades. These effects seem to influence things at the local administrative and community level. The implication, unsurprisingly, is that the inner workings of communities in countries matters for how events shape outcomes.

As with everything historical, the findings do not imply the outcomes will always be the same, or that the destinies of these communities is permanently cast forever. However, it should motivate researchers to dig a bit deeper into communities to better understand how some of the effects play out, and how future outcomes can be influenced.

Featured image credit: chain rust past by holdosi. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Long term effects of slave exporting in West Africa appeared first on OUPblog.

Brain waves, impulse control, and free will

In a delightful passage of his book Elbow Room, the philosopher Dan Dennett writes

“The first day I was ever in London, I found myself looking for the nearest Underground station. I noticed a stairway in the sidewalk labeled ‘SUBWAY’, which in Boston is our word for the Underground, so I confidently descended the stairs and marched forth looking for the trains. After wandering about in various galleries and corridors, I found another flight of stairs and somewhat dubiously climbed them to find myself on the sidewalk on the other side of the intersection from where I had started. I must have missed a turn, I thought, and walked back downstairs to try again. After what seemed to me to be an exhaustive search for hitherto overlooked turnstiles or side entrances, I emerged back on the sidewalk where I had started, feeling somewhat cheated. Then at last it dawned on me; I’d been making a sort of category mistake! Searching for the self or the soul can be somewhat like that. You enter the brain through the eye, march up the optic nerve, round and round the cortex, looking behind every neutron, and then, before you know it, you emerge into daylight on the spike of a motor never impulse, scratching your head and wondering where the self is.”

Lift your finger!

Searching for the self through perception raises quizzical questions, but searching for the self through action can leave us dumbfounded. Following Dennett, let’s enter the brain again, but in the opposite direction, that is, through your finger rather than through the eye. Think of what happens in your mind when you carry out the simple act of lifting your index. Typically, it doesn’t feel like much: your finger just goes up. At other times, however, and in particular when you’re thinking about what goes on when you lift your finger, you may come to distinguish between the moment you are intending to lift your finger, and the act itself. What happens during and before that brief interval has been the object of considerable research since the famous experiments of Benjamin Libet and colleagues (1983), who showed that the brain appears to engage in the neural processes that will lead to action well before the moment you feel the intention to act. This finding came as a surprise to many, for it overturns the intuitive perspective we entertain on ourselves as masters of our own domain: It feels like I am intending something, then doing it, but what really happens is that my brain acts, and I am only informed, late and en passant, so to speak, of what’s going on. Libet’s result appears to rob us of our own free will: Not only is what I do caused by the activity of my brain, but also what I intend to do.

None of us are free

But how could it be otherwise? It simply cannot be otherwise, as my mental states are necessarily caused by the activity of the brain. “I” cannot want anything beyond what my brain wants, “I” cannot be different from what the activity of my brain is, in constant interaction with itself, the world, and other people, consists in. Thus, we are looking at a loop that extends between the brain and the brain’s rendering of its own activity. Further, this loop is dynamical — extended both in time and in space. Early, local activity in certain brain regions progressively engage more and more brain regions to become a global brain event that we experience as a conscious state. Different experimental paradigms are catching different aspects and different moments of these neural processes and their subjective renderings, but they all unambiguously converge towards the idea that the mind is ultimately what the brain does.

Reconsidering Libet

With dualistic thoughts out of the way, we can now ask specific questions about the dynamics of decision-making. Schurger et al. (2012, see also Schurger, Mylopoulos & Rosenthal, 2015) recently showed that the gap between early brain activity and our subjective feeling of intending to act is perhaps not as large as Libet’s experiments initially suggested. The slow-rising lateralized readiness potential, the electrical signal that reflects preparation to action and that was (problematically) shown to begin much earlier than people’s own feeling of being about to act, is but a mere artefact, they argue. What happens instead is that random fluctuations in the activity of the brain cross a threshold at some point, and that point is both the moment at which people experience the urge to act and the moment at which they act. This result does not change the conclusion that all mental states are rooted in the brain’s activity, but they give some solace to those who felt it difficult to accept that conscious intentions come almost as a causally inert postdictive reconstruction of what the brain is doing.

Fighting against your own brain

Further, recent results also invite us to reconsider the extent to which we, as agents, have control over our actions. Thus, Schultze-Kraft et al. (2015) showed, using a compelling gamified situation where people fight against their own brain activity through a brain-computer interface system, that one can inhibit the early brain activity that will lead to action, up to about 200ms before the action becomes inevitable. This is Libet’s “free won’t” reinterpreted; arly brain activity that would normally lead to action begins to unfold: I, as an agent, become aware of this unfolding process shortly after it has begun, which gives me an opportunity to catch it before it completes.

« Free Will »: Are we all equal?

In our own recent study (Caspar & Cleeremans, 2016), we addressed essentially the same question through completely different means: we asked whether there are individual differences in the timing between the onset of the brain motor preparation, the moment of the conscious intention, and the action itself. Our hypothesis was that people who exhibit a short time window between their conscious decision to act and their action itself may have less time to inhibit the upcoming action. We therefore correlated these differences in timing with personality variables, in particular the impulsivity trait.

Figure courtesy of Emilie A. Caspar and Axel Cleeremans.

Figure courtesy of Emilie A. Caspar and Axel Cleeremans.We observed that the most impulsive individuals exhibited the shortest time window between the moment of their conscious intention to act and their keypress (see figure above). You can see that people who scored high on attentional and/or motor impulsivity were also those who reported the longest time window between the moment of their conscious intention (as indicated by more negative values) and the keypress. This suggests that individuals who score high on impulsivity have less time to inhibit their actions, and hence that global personality traits cast at the agent level influences both how the loopy sub-personal low-level neural processes that underpin behaviour unfold over time and the extent to which such processes are susceptible to be modified online.

This finding opens up many avenues for further research. May it be, for instance, that one can train oneself to become more sensitive to early signs of impending action and hence improve our ability to exert control over our own behaviour? Would similar findings obtain with other personality variables? More generally, our finding suggests that free will is not a given. Perhaps some of us — even if none of us could ever “do otherwise” — have more opportunities to exercise our freedom than others. As Dennett puts it, “Freedom evolves”…

Featured image credit: Underground. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Brain waves, impulse control, and free will appeared first on OUPblog.

Galileo’s legacy: Catholicism, Copernicanism, and conflict resolution

Four hundred years ago on 26 February 1616, Galileo Galilei was ordered by the Catholic Church to abandon his promotion of Copernican theory due to its perceived contradiction with certain biblical passages. His adherence to Copernicanism would later lead to his arrest for heresy. This famous historical conflict of ideas has been used by many as an example of the natural antagonism between scientific thought and organised religion, but is it that simple? In the extract below, Thomas Dixon explores the complex and often contradictory relationship between these two major powers in his book Science and Religion: A Very Short Introduction.

In Rome on 22 June 1633 an elderly man was found guilty by the Catholic Inquisition of rendering himself “vehemently suspected of heresy, namely, of having held and believed a doctrine which is false and contrary to the divine and Holy Scripture”. The doctrine in question was that “the sun is the centre of the world and does not move from east to west, that the earth moves and is not the centre of the world, and that one may hold and defend as probable an opinion after it has been declared and defined as contrary to Holy Scripture”. The guilty man was the 70-year-old Florentine philosopher Galileo Galilei, who was sentenced to imprisonment (a punishment that was later commuted to house arrest) and instructed to recite the seven penitential Psalms once a week for the next three years as a ‘salutary penance’. That included a weekly recitation of the particularly apt line addressed to God in Psalm 102: “In the beginning you laid the foundations of the earth, and the heavens are the work of your hands” Kneeling before the ‘Reverend Lord Cardinals, Inquisitors-General’, Galileo accepted his sentence, swore complete obedience to the ‘Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church’, and declared that he cursed and detested the ‘errors and heresies’ of which he had been suspected – namely belief in a sun-centred cosmos and in the movement of the earth.

It is hardly surprising that this humiliation of the most celebrated scientific thinker of his day by the Catholic Inquisition on the grounds of his beliefs about astronomy and their contradiction of the Bible should have been interpreted by some as evidence of an inevitable conflict between science and religion. The modern encounter between evolutionists and creationists has also seemed to reveal an on-going antagonism, although this time with science, rather than the church, in the ascendancy. The Victorian agnostic Thomas Huxley expressed this idea vividly in his review of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859).

“Extinguished theologians lie about the cradle of every science as the strangled snakes beside that of Hercules; and history records that whenever science and orthodoxy have been fairly opposed, the latter has been forced to retire from the lists, bleeding and crushed if not annihilated; scotched, if not slain.”

The image of conflict has also been attractive to some religious believers, who use it to portray themselves as members of an embattled but righteous minority struggling heroically to protect their faith against the oppressive and intolerant forces of science and materialism.

Portrait of Galileo Galilei by Justus Sustermans,1636. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Galileo Galilei by Justus Sustermans,1636. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Although the idea of warfare between science and religion remains widespread and popular, recent academic writing on the subject has been devoted primarily to undermining the notion of an inevitable conflict. As we shall see, there are good historical reasons for rejecting simple conflict stories. From Galileo’s trial in 17th-century Rome to modern American struggles over the latest form of anti-evolutionism, known as ‘Intelligent Design’, there has been more to the relationship between science and religion than meets the eye, and certainly more than just conflict. Pioneers of early modern science such as Isaac Newton and Robert Boyle saw their work as part of a religious enterprise devoted to understanding God’s creation. Galileo too thought that science and religion could exist in mutual harmony. The goal of a constructive and collaborative dialogue between science and religion has been endorsed by many Jews, Christians, and Muslims in the modern world. The idea that scientific and religious views are inevitably in tension is also contradicted by the large numbers of religious scientists who continue to see their research as a complement rather than a challenge to their faith, including the theoretical physicist John Polkinghorne, the former director of the Human Genome Project Francis S. Collins, and the astronomer Owen Gingerich, to name just a few.

Does that mean that conflict needs to be written out of our story altogether? Certainly not. The only thing to avoid is too narrow an idea of the kinds of conflicts one might expect to find between science and religion. The story is not always one of a heroic and open-minded scientist clashing with a reactionary and bigoted church. The bigotry, like the open-mindedness, is shared around on all sides – as are the quest for understanding, the love of truth, the use of rhetoric, and the compromising entanglements with the power of the state. Individuals, ideas, and institutions can and have come into conflict, or been resolved into harmony, in an endless array of different combinations.’

Featured image credit: Solar System. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Galileo’s legacy: Catholicism, Copernicanism, and conflict resolution appeared first on OUPblog.

March 10, 2016

Early detection of intentional harm in the human amygdala

Being able to detect if someone is about to physically harm us or those around us can be critical for survival, and our brains can make this assessment in tenths of a second. But what happens in the brain while we make these assessments, and how does it occur so fast?

If we see someone being harmed, our moral evaluation of the incident is near instant and is based on whether the harm caused was intentional, and if so how serious the intended harm was. An example of this would be if you witness a man being deliberately pushed in front of a train as it enters the station. Your moral appraisal of the perpetrator would not be altered by whether the victim was rescued before the train struck. You would recognize the perpetrator’s intent to severely harm their victim, whether successful or not, and blame them accordingly.

The study described in the video above used intracranial recordings to look inside participants’ brains to see how they react when confronted with examples of intentional harm, unintentional harm, and neutral actions. The results show that part of the brain called the amygdala displays early activity when faced with intentional harm. The amygdala was the only part of the brain able to recognize critical conditions that distinguished intentional from unintentional harm.

In short, the amygdala and its frontotemporal networks are responsible for the early recognition of the intention to harm and the moral evaluation of harmful actions.

Featured image – Taken from the ‘Early detection of intentional harm in the human amygdala’ video. Used with permission.

The post Early detection of intentional harm in the human amygdala appeared first on OUPblog.

Growing criticism by atheists of the New Atheism movement

We seem to be witnessing a broad reaction against the New Atheism movement by atheists as well as religious believers, whether undermining the idea of a long-standing conflict between science and religion, or taking a critical view of their political agenda. James Ryerson recently examined three new books (including my own) in the New York Times Book Review – a small sample of a growing body of work.

Many of today’s “New Atheists” reprise a nineteenth century argument about the “warfare of science with theology” (to use the title of one of the most well-known books of this genre by A.D. White published in the 1870s). There is a great deal of evidence that this cliché has little historical validity. For example, R. L. Numbers & K. Kampourakis question the idea that religion has obstructed scientific progress: many of the early pioneers of natural science were deeply religious; Copernicus’ theory was not immediately rejected by the Catholic Church (Copernicus held minor orders in the church and a cardinal wrote the introduction); and certain theologically based concepts like “natural law” were crucial for the development of science in the west. While some religious positions conflict with science (Ryerson’s example is “Intelligent Design”), there is little evidence to support a grotesquely over-generalized “conflict myth” regarding the larger story of the interaction of science and religion. If religion and science are not inevitably at war, there is no reason to think that science can serve as a pillar for an atheistic worldview. My own work is less historically oriented; instead it points to several places where those who try to use cognitive science to undermine religion are not necessarily either logically or empirically convincing in their arguments. There is no reason to think that science is necessarily or inevitably on the atheists’ side.

The New Atheism movement is receiving a powerful attack from another side as well — the politics implicit in their worldview. Two books published this year exemplify this critique, in which militant atheism is seen as an anti-progressive “secular fundamentalism.” C.J. Werleman, in The New Atheist Threat: The Dangerous Rise of Secular Extremists, himself formerly a militant atheist, describes the New Atheists’ uncritical devotion to science, their childish understanding of religion, their extreme Islamophobia, and intolerance of cultural diversity. All of this provides a rationalization for American imperialism vis-à-vis the Muslim world. Stephen LeDrew’s The Evolution of Atheism shows that atheism is not just the denial of belief in God but is itself a system of belief in a “secular ideology” with a particular cultural and political agenda, an agenda powered by a simplistic view of science and a rationalistic utopianism that “exhibits some totalitarian tendencies with respect to the use of power.” If religion no longer binds society together and undergirds morality, state power must take over. These, and other critics, argue that the “New Atheists” are a major source for the Islamophobia that plagues our nation right now and their ideology can easily be used as the basis for a hyper-individualistic, every man (the gender reference is intended) for himself politics in which the poor and less fortunate are cast aside and forgotten.

Undermining the New Atheism offers no necessary support for religion. There certainly are thoughtful atheists with a nuanced understanding of religion to whom these critiques, including my own, do not apply. The books referred to here do not demonstrate, or even claim, that atheism is false. But they add up to a conclusion that science and rationality are not necessarily on the side of atheism and that atheists cannot simply assert that science and rationality belong uniquely to them. Accepting this should eliminate some of the bitter sloganeering on both sides of the current atheism-theism discussion and so possibly make it more complex and more fruitful.

Featured image: Apples. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Growing criticism by atheists of the New Atheism movement appeared first on OUPblog.

Building library collections – change and review

Libraries have been primarily identified by their collections – by those accessing the resources collected by individual libraries and for those not directly engaging imagining access. When Borges wrote “Paradise is a library, not a garden” he captured the concept of the library as a palace for the mind, connecting readers to the generations of works – from maps, manuscripts and incunabula to the new online resources of today. If the physical form is the key to our identity, the question arises as to what our collections should be in such times of change. Many of these trends reflect fundamental changes in scholarly communication in the networked age that contribute to scholarship, often in anticipation of shifts in the academy and changes in scholarly communication.

In Australia, the Group of Eight comprises Australia’s eight leading research universities – The University of Melbourne, The Australian National University, The University of Sydney, The University of Queensland, The University of Western Australia, The University of Adelaide, Monash University and UNSW. Evaluations of the needs of academics and higher degree students undertaken in recent years suggest that the fundamental role of the library is multifaceted and increasingly supporting scholarly activities beyond physical collections.

Five of the university libraries undertook a study of current client needs and perceived roles using Ithaka S+R, a US based not-for-profit organisation with a tool that evaluates libraries. The study, conducted primarily of academics and postgraduates, found that the primary roles of the academic library were:

‘How important is it to you that your university library provides each of the functions below?’

1. Buyer– ‘The library pays for resources faculty members need, from academic journals to books to electronic databases’

4. Research- ‘The library provides active support that helps increase the productivity of my research and scholarship’

2. Archive- ‘The library serves as a repository of resources; in other words, it archives, preserves, and keeps track of resources’

5. Teaching- ‘The library supports and facilitates faculty teaching activities’

3. Gateway- ‘The library serves as a starting point or ‘gateway’ for locating information for faculty research’

6. Student support- ‘The library helps students develop research, critical analysis, and information literacy skills’

The study found a high value for the libraries as collectors and repositories, with strong emerging needs for research skills and support for education. These newer roles are even more significant in an online world where a single keystroke can delete a lifetime’s work. The complexity of the scholarly communication system is creating a need for new services. Interestingly, the nature and quality of services provided by libraries in the print environment translates to the capabilities required to support online scholarship. Expertise in dissemination of research, publishing expertise, managing research data as an archival asset are highly value added skills fully applicable in the online environment.

A different set of insights have been obtained from a study of academics and postgraduates undertaken by Professor Carol Tenopir, School of Information Sciences at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville and the Director of Research for the College of Communication and Information, and Director of the Center for Information and Communication Studies. A recent study at the Australian University added to the substantial research already undertaken as part of the Lib-Value project.

The overarching project has found the Australian university libraries are the strongest source of readings for academics and postgraduates. For comparison while UK and US libraries are also the primary sources for journals (67 and 55 per cent respectively), while Australian libraries are the source of 69 per cent of journal articles. Postgraduates overall have 69 per cent of their journal article readings from libraries and 51 per cent of books, 9 and 6 per cent higher respectively than in the US.

The study at the Australian National University provided a deep dive into information behaviours. The impact of libraries was significant. Academic staff who published 5-10 items in the last two years read the most books and other publications. The fundamental importance of the library is revealed in the time devoted by academics to reading. Academic staff on average spend 133 hours per year with library-provided material, equivalent to 16.6 eight-hour days annually reading material provided by the library.

Postgraduate students could well be analysed as living in the library. Postgraduate students, on average, spend 254 hours per year of their work time with library-provided material, or the equivalent of 31.75 eight-hour days annually. 100 per cent of postgraduate students used the library collections online.

Both these sets of studies point to a set of library services that are building and communicating knowledge in print and increasingly digital. The fundamental capabilities of libraries are being recognised as vital by students and academics challenged by the digital environment.

Changes: the exchange rate and collecting

Collection building can be affected by changes external to libraries and universities. The dramatic fall in the exchange rate in Australia over the past four years has had a significant effect on the purchasing power of libraries.

Collection review has seen a focused review across the region.

At the Australian National University Library, the review of titles, in particular subscriptions and databases, has built upon a methodology and process developed by Deakin University. The major factors taken into consideration are:

Relevance to research and teaching

Cost and use

Cost per use

Competitor products

Degree of uniqueness

Workflow costs – cataloguing, processing

In continuing to develop the whole collection, the library is conscious that:

the value in resources is not just immediate use, longer term issues of research and teaching need to be considered

we are curating a collection that needs to serve a community with a strong corpus of knowledge that can be seen as an integrated collection built over time

there are opportunity costs – some resources must be acquired while they are available as they may only be available for purchase for a short period of time.

The scholars of the future

Overall the building of collections is key to the library’s role in supporting the scholars of the present and future. The complex nature of collections and resources means that while we need to move budget to invest in growth of services such as data management, the collection remains critical to delivering support for research and teaching.

These new roles for the library position the flourishing of research capabilities and knowledge that support the next generation of policy makers, researchers and community members.

Creating a world where knowledge and scholarly communication capabilities are greater will remain a major challenge for the future.

At the recent conference Scholarly communication beyond paywalls, it was clear that the current model of control of scholarly outputs is insufficient to support an innovative, knowledge based world. While open access policies and movements have achieved much, the majority of scholarly works remain inaccessible to many. We need to work with publishers to deliver a new world in the coming years.

Image credit: Bookshelf by Unsplash, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Building library collections – change and review appeared first on OUPblog.

Q&A with social worker Anderson Al Wazni

March is National Social Work Month. This year’s theme is Forging Solutions Out of Challenges. One social worker who is forging ahead is Anderson Al Wazni of Raleigh, NC. Anderson’s research and passion explores Muslim women’s feminist identity and empowerment in her community and beyond. We sat down with Anderson to discuss her role as a social worker and future plans.

Why did you become a social worker?

My experiences in both my personal and academic life led to my desire to become a social worker. I have always been involved in either environmental or humanitarian work since high school, but I did not necessarily tie in my academic career into these interests. I began in religious studies but had a few life changing experiences during undergrad that set me on a path for social work. I was fortunate to receive a number of international scholarships that sent me to South and Southeast Asia to live and study amongst various religious groups and foreign languages that I was studying at the time. Traveling changes people for the better, as it opens your mind to bigger issues and brings into focus how interconnected people are. Policies that your home country enacts can have very positive or very detrimental impacts on people you may never ordinarily come in contact with. I began to shift my interest to international policy, but was also humbled by the work I saw by the NGOs and local ‘social work’ organizations in the field of human trafficking, rural healthcare, and environmental pollution. I think we assume that America has a more advanced model for social work, but that has not been my experience. The on the ground work I saw by social workers in India and Bangladesh was so progressive, and completely changed my view of what I, as a single person, could do to help bring about real, tangible change. Although I am still very committed to policy, I wanted to receive a clinical social work education that keeps the personal aspect in my work. I strongly feel that social work has the potential to keep the human face on issues that can easily become depersonalized and I wanted to be a part of this field. I began with a general interest in women’s rights and culturally competent healthcare, but as I gained experience in the field I ended up finding my specific niche in advocating for Muslim women and feminist identities.

Describe your role as a social worker.

I did not take the expected or typical path after completing my MSW, considering my school was clinically focused. I wanted clinical experience, but I always knew my work would trend towards the macro. I completed my thesis research on Muslim women who wear hijab, feminist identity, and body image and adapted this into an article. That was the launching pad for me to continue to write and speak on this topic, and I have made it my life’s work. I have always been passionate for writing and recognize the influence that the written word can have on opening people’s minds to problems right in front of them that they did not recognize, or by introducing them to people and ideas they may not have encountered. I feel through writing and speaking, I am best able to address “big issues” such as Islamophobia, countering radical ideology, and political propaganda that impacts the every day lives of people in our country as well as abroad.

Image: Photo of Anderson Al Wazni. Used with permission.

Image: Photo of Anderson Al Wazni. Used with permission.

What do you hope to see in the coming years from the field?

I would love to see a better integration and collaboration between policy advocates and clinicians. It’s not that this does not already exist, but I think as a field we have a ways to go. I have experienced a strong divide between the two where we get in our heads that to enact change one way is better than the other. The reality is no actual change happens if we don’t see how poor policy leads to poor mental health or that clinicians have tangible evidence of how policy negatively or positively impacts people in their every day lives.

Your research includes a study on Muslim women in America and hijab. Tell us more about your work.

My research was conducted amongst Muslim women who wear the hijab and what their experiences are with feminist identity, female empowerment, and body image. The way in which Muslim women who veil are depicted in our culture is deplorable and often unfairly shown as the embodiment of patriarchy, terrorism, and total subjugation of women. If you stop to consider when and how you see Muslims depicted in the media it’s never positive– it’s the abused housewife, the honor killing, the tyrannical man, or the terrorist. I have yet to see an average Muslim family in a commercial selling you toothpaste or as a regularly occurring character in a TV show in which their Muslim identity is not the focus. Yes, it is absolutely true that there have been radical political and ideological movements that have forced the hijab on women, but that is not the majority of nearly 2 billion Muslims on Earth, and that applies even less to American Muslim women. What people have not stopped to consider is how Western economic and political movements have outright exploited women’s rights groups and feminist imagery to sell us the image of what women ought to look like if they are “free.” There’s a really dark side to feminist history and colonialism in the “Islamic world” that we have turned a blind eye to. That has absolutely impacted how Muslim women are viewed in our current sociopolitical climate.

I have considered myself to be a feminist from a pretty early age and did not realize that once I decided to wear my hijab full time, my feminist card had been revoked. I wanted to hear from other women what their lives were like as a veiled woman in America. What did they think about feminism and women’s rights and how, if at all, does their hijab impact this? The data speaks for itself; Muslim women are no more likely to be oppressed by choosing to wear a hijab and many of them are outspoken on women’s rights. We are at a breaking point in our culture; with really hateful language being thrown around by people in public office and horrific hate crimes like the murder of the three Chapel Hill students amongst countless verbal and physical assaults reported every week. I’m not waiting around for politicians to get it together, the change starts with us and it begins by breaking down assumptions we have about each other. Muslim women who wear hijab and Muslim women who do not wear hijab are both allies in democracy, and it’s up to us to push past caricatures of who we are to work together to bring about change and genuine tolerance.

What are your future plans in your work?

I hope to continue writing and to branch out into public speaking in the next year, as well as reaching out to younger generations of Muslim women to help empower them to be proud and confident about their identity. Despite the intense and even ridiculous political climate we are currently living in, I do have a lot of hope for the future. With the current refugee crisis and rise of tyrannical groups like ISIS, there is a lot of work to do. I recognize I have a role both within the Muslim community as I do in the political and sociocultural world outside of it. I hope that my small contribution helps us to realize we have more in common than not and that Muslim women can help pioneer progressive change that we need. I am not Muslim and an American. I am an American Muslim and I am as committed to democracy, women’s rights, and eradicating oppression as anyone else.

Featured image credit: girl schoolgirl learn by Wikilmages. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Q&A with social worker Anderson Al Wazni appeared first on OUPblog.

Deception and the eye of the beholder

Deception is rife in nature, from spiders that mimic ants for protection through to carnivorous plants that lure insects with attractive smells. As highly visual animals ourselves it’s only natural that we humans often judge the appearance of other species through our own senses. However, if we want to understand how animals communicate with one another, and how they are exploited by others, we need to get inside their minds, or at least their sensory systems.

Nature is full of bright colours and patterns, but how different animals see the world varies substantially. Humans (with ‘normal’ colour vision) see colours by comparing the responses of three types of cell in the eye, called cones. These are sensitive to shorter (‘blue’), medium (‘green’), and longer (‘red’) wavelengths of light, and provide us with trichromatic vision. Other animals don’t see colours in the same way. Many mammals like dogs and cats have just two cone types and are dichromatic – they can’t discriminate between colours that we see as red, green, and yellow. On the other hand, most birds are probably tetrachromatic and see colours with four cone types, including one sensitive to ultraviolet (UV) light, to which we are blind. There exists considerable variation among invertebrates too. In short, our interpretation of the world is a construct of our sensory systems and brain.

A European crab spider Synema globosum matching the colour of the flower it sits on waiting for prey to come near. In Australian crab spiders, some species lure prey not through camouflage but with bright ultraviolet colours. Photograph by Martin Stevens. Do not re-use without permission.

A European crab spider Synema globosum matching the colour of the flower it sits on waiting for prey to come near. In Australian crab spiders, some species lure prey not through camouflage but with bright ultraviolet colours. Photograph by Martin Stevens. Do not re-use without permission.To appreciate how deception works, we need to know something about how the exploited animal perceives the world. Crab spiders provide a nice example. Many European species match the colour of the flowers they sit on, and through their camouflage wait for unsuspecting prey to come close. Australian crab spiders don’t follow this pattern, however. If we image some of those species under UV light, they glow and stand out like a beacon. Why they do this is revealed in understanding the vision of many pollinating insects, such as bees, who have excellent UV vision. The crab spiders lure pollinators towards them with attractive bright UV signals.

The flip side is that understanding vision can also shed light on why deception to our eyes doesn’t always seem impressive. For example, some Cryptostylis ‘tongue’ orchids lure one species of pollinating wasp without providing any reward (no nectar). Specifically, they attract male wasps who are tricked into ‘thinking’ that the flowers are a female, with which they try to mate. To us, the resemblance is not especially good, either in colour or pattern. However, wasps have a visual system that is poor at seeing red colours and their compound eyes are not very effective at resolving fine detail in shape and pattern. Research, modelling the vision of the wasps, has shown that to their visual systems, the mimicry by the orchids is actually very effective.

Understanding how vision works can also shed light on how signals evolve to exploit the behaviour and responses of other animals. In the ancestors of some modern primates, including humans, colour vision underwent an evolutionary change from a dichromatic state to trichromacy. One of the major reasons seems to be that trichromatic vision enabled individuals to detect ripe red and yellow fruit from a backdrop of green leaves, something that isn’t easy for dichromatic mammals.

A flower seen through human vision (top) and represented to bee vision (bottom). Photograph by Martin Stevens. Do not re-use without permission.

A flower seen through human vision (top) and represented to bee vision (bottom). Photograph by Martin Stevens. Do not re-use without permission.Subsequently it seems, many of these trichromatic primate groups evolved red faces and other red signals in mating and dominance interactions because they elicited a greater response in the visual system of mates and rivals. So red signals in these animals arose because the ability to see red had already evolved for another function.

Deception is far from limited to vision. It’s common in other sensory modalities too, such as hearing. Over millions of years bats, many of which hunt by broadcasting high frequency ultrasonic echolocation calls, have exerted considerable selection pressure on insects. The frequency of these calls is well beyond our natural hearing range. In an evolutionary arms race, as bats have evolved increasingly specialist echolocation skills, insects have evolved a range of defences. One of these is hearing organs, which have arisen multiple times independently in many insect groups. These ears have in many cases evolved to detect the ultrasonic calls of bats, so that the moth, for example, can take evasive action. A major development is that, just like with the red-faced primates, hearing and sound production has also been adapted for other functions like mating, and often in a deceptive manner.

Work by Ryo Nakano and colleagues has shown that some male moths produce ultrasonic courtship songs that are highly effective at stimulating female hearing. When they prevented males from making their songs, mating success declined considerably. However, when the muted males were accompanied with playbacks of songs through speakers, mating success was restored. This was not the case when playing white noise instead. The remarkable thing, however, is that in one experiment, with a moth called the common cutworm (Spodoptera litura), when the scientists played back bat echolocation calls, male mating success was also effectively restored. Over evolution, female moths evolved a freeze response for when they hear ultrasonic bat calls, and the male songs exploit this by causing females to pause, essentially preventing the female from running away. Interestingly, in other moths, males produce calls that cause rival males to freeze too.

All in all then, deception is in the sense of the beholder, and without understanding how other animals perceive the world we often can’t appreciate how deception has evolved and works.

Featured image credit: Bonnet Orchid – Cryptostylis erecta, by David Lochlin. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Deception and the eye of the beholder appeared first on OUPblog.

March 9, 2016

In memoriam: Sir George Martin, CBE, 1926-2016

George Martin’s contributions to the way we hear music today are incalculable. Many describe him as the “fifth Beatle,” and his work with those musicians certainly warrants recognition, but his contributions to recorded sound in the twentieth century go far beyond that epithet. In an era when record company marketing lauded hyperbolic praise on stars and some producers presented themselves as supreme geniuses, George Martin maintained a relatively discreet presence. Instead, he took the role of enabler-in-chief, as generous in his praise as he was with his gifts for helping musicians create their best work.

The son of a North London carpenter, George Martin in his autobiography describes how during the depression his mother’s middle class background influenced his parents’ decision to financially support his musical interests. During the evacuation of London during the blitz he studied at Bromley Grammar School where Martin proved an eager adolescent musician, developing his musical ear, teaching himself basic theory and harmony, and leading a dance band (George Martin and the Four Tune Tellers). Upon graduation towards the end of the war, he served in the Royal Navy, Fleet Air Arm, earning an officer’s commission, and on demobilization in 1947 he enrolled at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, studying composition, arranging, conducting, theory, piano, and oboe during his three years at that institution.

Finding work as a musician in postwar Britain had challenges, but Martin had impressed his teachers and his mentor at the Guildhall recommended him to the director of Parlophone Records as an assistant. Oscar Preuss initially assigned Martin to work on the label’s classical catalogue, which consisted largely of chamber music; but Martin gradually added jazz (e.g., Humphrey Lyttelton), developed the label’s Scottish music catalogue (e.g., Jimmy Shand), and built the comedy component (e.g., Peter Ustinov). Nevertheless, EMI’s other labels—Columbia and HMV—were capturing an increasing share of the growing and lucrative British pop-music market, and Preuss knew that he needed someone younger to negotiate the major changes that were sweeping the business. When Preuss retired in 1955, EMI appointed Martin (29) as his successor, the youngest director to oversee an EMI label at the time. Under Martin, Parlophone would sign Adam Faith (recorded by John Burgess) to its roster as well as The Vipers Skiffle Group (recorded by Martin).

In the spring of 1962, Martin listened to selections from The Beatles’ failed Decca audition, parts of which must have made him wince, but he agreed to give them a recording test after intercessions from Ardmore and Beechwood’s Sid Colman and EMI managing director L. G. Wood. John Lennon and Paul McCartney’s compositions had piqued Colman’s interest, while Wood knew that The Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein owned the largest and most influential record store in England’s northwest. On Wednesday 6 June 1962, The Beatles knew they were in the studio because their songs had attracted the attention of a publisher and, eager to demonstrate their potential, they had resurrected and rehearsed three original compositions. Nevertheless, George Martin and his production team, while impressed with the group’s charm and humor, doubted their potential as songwriters. Balance engineer Norman Smith remembered that, “We saw no potential of their songwriting abilities that were to come.” However, he was impressed with the band’s presence and offered, “My thought… George, I think we should sign them.”

Even as they respected his accomplishments, some musicians of the era did find Martin’s demeanor condescending, but this impression likely derived in part from his fatherly inclination to develop the talents of the performers with whom he worked, whether comedians like Peter Sellers, novice singers like Cilla Black, or consummate professionals like Shirley Bassey. He applied his musical ear to create arrangements for Black, Gerry and The Pacemakers, and others, and to encourage the musicians he encountered to grow as artists. His work with The Beatles has the best documentation, but many other artists benefitted from his talents.

Most of his work remained hidden from the public, but some exceptions show how much artists appreciated him. For example, Cilla Black (who passed away last year) in concert footage of a performance with an orchestra led by Martin, mistimes her entry and, with the camera on her, recognizes her mistake with a look of suppressed panic. Behind her, Martin deftly resynchronizes the orchestra to return Black into the arrangement by Johnny Pearson. The palpable relief on her face gives way to an embrace of the emotions of the song. At the end, she turns and curtsies to Martin who returns the acknowledgement with a gentlemanly bow.

Cilla Black, “Anyone Who Had a Heart”:

The Beatles represent his best-known students, developing their interests in the possibilities of the studio and in the art of recording. McCartney in particular learned from Martin and relied on him to help realize his increasingly ambitious ideas, whether in the realization of his melodies in the film music for The Family Way (1966), the psychedelic orchestral bridges in “A Day in the Life” (1967), or his Bond theme “Live or Let Die” (1973).

“Love in the Open Air” (The Family Way):

For all students interested in how modern popular music evolved, Martin’s career demonstrates the interplay between technological innovations and cultural adaptation. When he arrived at EMI, recording engineers still cut recordings into hot wax with lathes and he witnessed the transition from that medium to magnetic tape and, eventually, digital recording. As importantly, he initiated one of the biggest coups in British recording industry when he colluded with some of the most successful producers of the day to form their own production company, Associated Independent Recording (AIR), which remains an important studio. His recognition that corporations reaped substantial profits from their recordings while paying them relatively inconsequential salaries inspired him to lead a producers’ revolt that initiated major changes for London record companies.

More importantly, his productions have shaped our expectations for recorded music in profound ways. Every band that wants their record to have the sound of The Beatles aspires to George Martin’s production values. Film composers looking for the power of Shirley Bassey’s “Goldfinger” (perhaps the most effective of all the Bond scores) have George Martin as their model. And for those whose professional goals include a balance between musical sophistication and gentlemanly humility, few better examples could be found than George Martin.

Sir George Henry Martin CBE

3 January 1926 – 8 March 2016

LAS VEGAS – JUNE 30: Producer Sir George Martin, the original producer for the Beatles, arrives at the gala premiere of “The Beatles LOVE by Cirque du Soleil” at the Mirage Hotel & Casino June 30, 2006 in Las Vegas, Nevada. (Photo by Ethan Miller/Getty Images)

LAS VEGAS – JUNE 30: Producer Sir George Martin, the original producer for the Beatles, arrives at the gala premiere of “The Beatles LOVE by Cirque du Soleil” at the Mirage Hotel & Casino June 30, 2006 in Las Vegas, Nevada. (Photo by Ethan Miller/Getty Images)Image credits: George Martin / Vintage radios via iStock.

The post In memoriam: Sir George Martin, CBE, 1926-2016 appeared first on OUPblog.

Bosom friends, bosom serpents, and breast pockets

Last week I mentioned my “strong suspicion” that bosom has the same root (“to inflate”) as the verb boast. As a matter of fact, it was a conviction, not a suspicion, but I did not want to show my cards too early. Before plunging into matters etymological, perhaps something should be said about the word’s bizarre spelling. The Old English form was bōsm. (The sign—it is called macron—over the vowel designates length. I finally decided to start using this diacritic rather than explaining every time: long o as in Modern Engl. awe in the pronunciation of those who distinguish shah and Shaw. My exasperation reached the breaking point several weeks ago, when I was explaining to a student that the past tense of a certain verb has long o. “Yes, I understand,” he replied: “Ah.” Enough is enough.) By the Great Vowel Shift, the change to which we owe today’s pronunciation of Engl. a, e, i, and o, among others, closed ō became ū. In Modern English orthography, it is rather regularly designated by oo. The sound may be short (as in good) or long (as in food). Therefore, foreigners seeing hood for the first time tend to mispronounce it. In many Middle English words, short u often yielded the vowel we hear in come and other, which, unfortunately, do not rhyme with dome and bother. Our foreigner is now nonplused by smother, over, hover and shove. However, there is hardly any other English word in which single o designates short u, as it does in bosom. To be sure, s between vowels is also ambiguous: compare cease and tease, but this is a relatively minor nuisance. Conclusion: modern spelling must be destroyed — delenda est.

Bosom has cognates in all the West Germanic languages (German, Dutch, Old Saxon, and Old Frisian), but not in Scandinavian. In Gothic it did not turn up either. Most probably, it was a West Germanic coinage that did not spread to the neighboring areas. However, its etymology seems to have been discovered, so that the statement origin unknown in our dictionaries has no justification. We can dismiss as unprofitable guessing the early attempts to derive bosom from Greek and French, from the word bath (because the bosom is full of warmth), and from some verb meaning “to beget, to produce.”

Dead boughs and a dead end for this etymology

Dead boughs and a dead end for this etymologyIn this case, serious study began with Jacob Grimm. The German congener of bosom is Busen, and Grimm’s forms were also German, but I will substitute English equivalents for them. He considered a tie between bosom and either bow “to bend” or bow “the front of the ship,” or possibly bough. Though all of them had the same root (bug-, bog-, etc.: don’t miss final –g!), the choice of the form is important for semantic reconstruction. Depending on our preference, bosom emerges as a bent thing or as the front of the body, or as something rounded. Bough is especially attractive, because in Old English it meant “shoulder”; bosom could then be interpreted as the distance between the shoulders. The similarity between the phonetic shape of bosom and fathom was noticed long before Grimm. Indeed, both words have the same ancient suffix, and fathom once meant “embrace.” Friedrich Kluge shared Grimm’s view of Busen. For a long time he was looked upon, quite deservedly, as the greatest specialist in the area, and few people chose to disagree with him. (However, his pupils and followers, in the posthumous editions of his etymological dictionary of German, revised the entry. This is a feat without analogs in English: no one dared to revise Skeat’s masterpiece.)

It is at this stage that both Skeat and Murray found the scholarship on bosom. Skeat tentatively accepted Grimm’s etymology, while Murray neither endorsed nor rejected it. Nor did he hide behind the rather common advice to consult Mueller and Wedgwood (“and others”) for details. Mueller, a serious German etymologist of English, about the only predecessor whom Skeat respected, had nothing interesting to say (the entry in the second edition is more reasonable than in the first), while Wedgwood, incomprehensibly, omitted bosom; it is absent from all four editions of his dictionary.

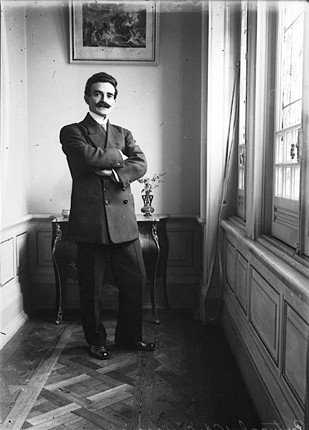

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. They were not only brothers but also bosom friends

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. They were not only brothers but also bosom friendsGrimm’s idea had a fatal flaw: it depended on the presence of either g or h after the vowel in bosom ~ Busen. No recorded form has any trace of such a consonant, and no one can explain why it disappeared if it ever stood there. For some time, researchers kept offering improved versions of the mythic bogsom or bohsom, but this was evidently a dead end. Later, the study of the origin of bosom became more realistic, but English lexicographers ignored the progress made since the appearance of the first volume of the OED and, as noted, found refuge in the fireproof verdict “origin unknown.” The users can think that no one has even tried to break the spell on this dismally misspelled word. Even Skeat, who followed the scholarly literature until the end of his life, stated in the fourth (last) edition of his dictionary (1910), after mentioning the most plausible hypothesis on bosom, that its origin is unknown!

Early etymologists were not quite sure where in the word bosom the root ended and the suffix began bo–som or bos–om? As we have seen, the oldest form was bōsm; consequently, in both German and English the second vowel is not original. Such insertions (epentheses) are common before m and n. At present, some people pronounce chasm, spasm, orgasm, and the like with a clearly audible schwa between s (that is, z) and m. When preceded by a vowel, groups of this type form a syllable regardless of schwa, and it matters little that garden has the letter e after d, while in rhythm m occurs immediately after th. German Busen once also ended in -m (its –n is relatively late; Dutch, like English, retained –m: boezem), and, if Engl. bosom were spelled bosem or bosam, or bosum, nothing would have changed with regard to its pronunciation. Old words of similar structure (for example, fathom and besom, from fæþm and besma ~ besema) show that the suffix in bōsm was –m.

Double-breasted, not double-bosomed.

Double-breasted, not double-bosomed.The root bōs – compares effortlessly with Sanskrit bhās – and yields the sense “to blow, to puff.” Bōsm must have been coined to denote the swelling of the breast. And this is what Skeat said in the fourth edition of his dictionary. It is therefore puzzling why he added the origin unknown phrase to his conclusion. Bows and boughs are now “out of the saga.” The origin of bosom is known, and we only have to understand why the speakers of West Germanic needed this word in addition to the Common Germanic breast, but, to answer this question, we need an essay on breast, its meaning and etymology. Such an essay cannot be given as a postscript to the present story. Perhaps later, if I have enough to say on the subject, I’ll return to breast. In the meantime, our readers may consult my old post on brisket.

Bosom is a more elevated word than breast, though in many cases they are interchangeable. Thus, noble feelings can fill one’s breast and rage in one’s bosom, but breast pockets cannot be called bosom pockets, and bosom friends cannot be called breast friends. Yet a bosom serpent lives inside the body: neither in the bosom nor in the breast. Usage is capricious. More than a century ago, it was suggested that bosom had at one time meant “woman’s breast,” with reference to Latvian pups “woman’s breast” and paupt “to swell up.” This idea occurs in at least two later good dictionaries, but it has probably to be rejected because the same Germanic word could mean “bosom” and “womb” (both swelled), and German has developed so many senses of Busen, including “sea bay” (the main meaning), “funnel,” and “jacket” (both dialectal), that the development from “a woman’s breast” seems unlikely. Bosom was coined to designate a broad, inflatable surface. Could fathom influence bosom? Hardly so, but the spelling with –om may indeed owe its origin to the proximity of the two nouns.

Image credits: (1) Хмиз. Photo by В.С.Білецький. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Doppelporträt der Brüder Jacob und Wilhelm Grimm by Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann (1855). Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) José Guilherme Macieira by Charles Chusseau-Flaviens. George Eastman House. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Bosom friends, bosom serpents, and breast pockets appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers