Oxford University Press's Blog, page 533

March 19, 2016

Potential dangers of glyphosate weed killers

What do Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Sri Lanka, El Salvador, Brazil, and India have in common? They have banned the use of Roundup—the most heavily applied herbicide in the United States. Why have these nations acted against what is the most heavily used herbicide in the world today? This is because of growing reports of serious illness to farmworkers and their families. Thanks to a little known provision in US law governing pesticides (the overarching category defined by the EPA for pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, and rodenticides), industry experts sit side by side with government officials in determining what is and is not toxic. In these other nations, far less cozy arrangements exist and reports of tragic illness have spurred direct and immediate actions.

To understand what inspired these disparate nations to restrict a pesticide widely dispersed in garages, schoolyards, golf courses, and farmland around America today, it’s important to consider the close tie between glyphosate (the main ingredient in Roundup) and the production of corn, cotton, soybeans, alfalfa, canola, sorghum, sugar beets, and wheat. Seeds for these major US commercial crops have been genetically engineered to resist the toxic effect Roundup has on weeds. Physicians report that rates of serious birth defects in one of Argentina’s poorest regions, Chaco, quadrupled the decade after glyphosate was introduced, while that of chronic kidney disease is soaring in young men and women in Central America, India, and other heavily sprayed regions.

This past June, a group of experts advising the World Health Organization (WHO) known as the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) unanimously determined that glyphosate is probably a human carcinogen (“Group 2A” in the IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans). Other agents identified as Group 2A include jet fuel, engine exhausts, a number of pesticides, and tars—all of which are subject to stringent controls today. More recently, nearly 100 scientists joined in rejecting the European Food Safety Agency assurance that Roundup was not toxic.

Herbicide by wuzefe. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Herbicide by wuzefe. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Underlying the WHO evaluations over the past four decades is one simple fact: Every agent known to cause cancer in humans also causes it in animals when adequately studied. Whenever experimental studies indicate a compound causes cancer in animals, it should be regarded as if it causes cancer in humans.

If glyphosate were a drug, it would never have been allowed to market.

Drugs are put into medical practice only after experiments establish that a novel agent might alleviate disease in animals. Monsanto began selling glyphosate in Roundup in 1973. It didn’t complete animal tests until 1981. When those tests produced a rare form of kidney cancer, industry sponsored scientists effectively discredited them.

In the case of glyphosate and cancer, one important animal study stands out. That study used a type of mouse bred to never get the disease. Four animals exposed to glyphosate developed the same very rare cancer in a single study. Not a single case of cancer was expected. The chances of that happening are close to one in a billion. Of course, people are not rodents. But the human genome project has shown that we differ from the mouse by less than one percent of all our genetic material. If studies with mice guide the pharmaceutical industry, how can we deny their relevance to toxic chemicals?

With tobacco, asbestos, vinyl chloride, hormone replacement therapy, diagnostic radiation, some metals, exhaust gases, chlorinated solvents, and a host of other agents, we got it backwards. Reports of their detrimental impacts surfaced decades before steps were finally taken to discourage their widespread use.

We are flying blind when it comes to understanding the risks of glyphosate—along with malathion and diazonon and other pesticides—because we have assumed them to be innocent until proven guilty. To the contrary, pesticides should not be accorded the rights of the accused in a criminal trial. By their very nature pesticides are designed to kill things and indeed there are times, as with epidemics such as equine-encephalitis, that we need to employ them for that purpose.

Studies of people with high exposures to glyphosate or other pesticides, including farmers, pesticide applicators, crop duster pilots, and manufacturers, have found high rates of blood and lymphatic system cancers, cancers of the lip, stomach, lung, brain, and prostate, as well as melanoma and other skin cancers. But what about the rest of us who may be exposed as golfers, lawn applicators, home gardeners, school children, ball players, and the like? We must rely on animal experiments, coupled with studies of those with high exposures, to predict risk in order to prevent harm.

What are we to do now? While industry spokespersons assure us that these other governments are just uninformed and ill-advised, their growing numbers alone should give us pause. There’s been a disturbing pattern in US law of late that places us all at risk. Recent interpretations of the Daubert standard of evidence increasingly mean that only after harm has been demonstrated to have taken place can steps be taken to reduce exposures to a suspect agent. This ignores and undermines the fundamental goal of public health: Preventing harm by reducing risk.

With glyphosate and other toxic agents we cannot and should not wait for additional proof that low levels of exposure affect our health, before taking steps to reduce our exposures. We must rely on animal experiments coupled with studies of those with high exposures in efforts to reduce the burden of cancer and other diseases. To do otherwise treats ourselves and our children as lab rats in an experiment without any controls.

Featured image credit: Crop by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Potential dangers of glyphosate weed killers appeared first on OUPblog.

The Great Pottery Throw Down and language

The newest knockout competition on British television is The Great Pottery Throw Down (GPTD), in which an initial ten potters produce a variety of ceramic work each week, the most successful being declared Top Potter, and the least successful being ‘asked to leave’. The last four then compete in a final for the overall title. While the format is very familiar from the likes of The Great British Bake Off and Masterchef, some of the words used in it may not be.

The Great British what?

The first thing of linguistic interest that I noticed was actually the title itself. Apart from the fact that expressions like throw-down and bake-off are, conventionally, hyphenated, why ‘throw-down’ at all?

A throw-down can be a fall in wrestling, but I don’t suppose many viewers will have been distracted by that, let alone misled into thinking the programme had something to do with both pottery and wrestling. Slightly closer, a throwdown is also, in an originally American sense, ‘a performance by, or competition between, DJs, rappers, or similar artistes’. While the world of competitive pottery may have no more in common with rapping than it does with wrestling, the producers are punning on the idea of throwing pots (to which I’ll return below).

By contrast, bake-off already meant ‘a contest in which cooks prepare baked goods such as bread and cakes for judging’. It does also, though, refer (in the grocery trade) to baked goods such as bread and cakes that are supplied to shops part-baked and then ‘baked off’ in the shops’ own ovens for freshness and, no doubt, that tempting ‘just-baked’ aroma wafting around the shop.

The title of GPTD could conceivably have been The Great British Throw Off, on the pattern of Bake Off, the ‘dreaded Dance Off’ in Strictly Come Dancing, and a play-off such as that for third place in a competition like the football World Cup. A throw-off is in fact the release of hounds at the start of a hunt, so not familiar or closely related enough to have caused confusion, but to throw something off is to produce it quickly and quite probably in a slapdash or offhand manner, which would not have been a desirable connotation.

Throwing biscuits?

In any specialist field, I am interested in words that have a very different meaning from the best known one, like a sheet on a sailing boat, which sounds like a sail, but is in fact a rope attached to a sail, used for keeping it at an angle where the wind acts on it. Some of the most striking such words in pottery are throw, turn, biscuit, bisque, slip, and wedge.

One of the central terms to potting is to throw – hence its mention in the title. Throwing is shaping clay with the hands while it is stuck to a rotating horizontal wheel. The immediately resulting bowl, vase, plate, etc. is perfectly round (barring the odd imperfection), but it can then be reshaped while it is still soft, to form a spout on a jug, for instance, and it can be remodelled at various subsequent stages by cutting pieces off, adding a handle, and so on.

Early on in the first round, the origin of to throw was explained. It’s often assumed that it lies in the practice of slamming the clay down on the wheel to make it stick, and the title The Great British Throw Down tends to reinforce that assumption. However, as the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) records, the earliest forms of the word, in Old English, meant ‘to turn’ or ‘to twist’, and the first recorded use in a pottery sense is from 1440.

Throw is related to the modern German word drehen, which means ‘to turn, revolve’, and it is interesting that it too has a pottery sense in Drehscheibe (literally a ‘turning disc’), which is one word for a potter’s wheel.

The OED records that throw can also mean to shape wood with cutting tools while it is rotating in a lathe, for which the more common word is turn, as in woodturning. To complicate things even more, to turn is also used in pottery, meaning to shape a pot with metal tools while it revolves on a wheel, in a process similar to woodturning. That is done when the pot has partly dried out and will hold its shape when being cut into, and this condition is known as leather-hard, another term used on the programme.

The word biscuit is doubly confusing, because not only does it here refer to pottery at a particular stage in its making, rather than a food item, but it also belies its own etymology. To start at the beginning, the Throw Down defined the term in Episode 1: ‘A pot’s first trip to the kiln is known as the biscuit firing, and it permanently transforms the clay.’ In other words, the pot is heated to around 1000º Celsius, causing chemical changes that harden it. The word biscuit is from Old French, and literally means ‘cooked twice’ because biscuits were originally baked normally and then dried out to make them keep, like present-day rusks or biscotti (the equivalent word in Italian). Biscuit also means pottery itself that has been fired in this way but not glazed. Most pottery is then glaze-fired, at an even higher temperature, to produce a waterproof glass-like coating, so, while some edible biscuits have been baked twice, as their name suggests, biscuit-fired pots, paradoxically, have only had one of the two firings that most pottery undergoes.

Bisque is an alternative word for biscuit and likewise more commonly means a food, in this case shellfish soup.

Slip has featured a lot in the rounds of the competition. It is thin, watered-down clay with two main purposes: usually with a pigment added, it is spread over unfired pieces by brushing, dipping, or pouring, in order to colour them. It is also used in slip casting, where it is poured into a mould and allowed to dry to create either solid or thin-walled shapes. How slip has come to mean this is obscure, but there may be a connection with the Norwegian word slip(a), which means ‘slime’.

Wedging is kneading clay before it is used, in order to homogenize it and get rid of air bubbles – boring but necessary, although some people make an art of it. If you don’t wedge clay enough, uneven consistency can make a pot crack in the firing, and an air bubble can make it explode – not popular with other potters who have pieces in the kiln at the same time.

What’s the difference between pottery and ceramics?

The contestants and judges in GPTD talk about pottery, potting, and pots, as well as ceramic and ceramics, but there is essentially no difference between pottery and ceramics – Oxford Dictionaries define a potter as ‘a person who makes ceramic ware’, and, of the two judges, Kate Malone is described as a ‘ceramic artist’ in GPTD but a ‘studio potter’ in an Observer Magazine article (6 December 2015), while Keith Brymer Jones is called a ‘potter’ in GPTD but a ‘ceramicist’ in the Observer.

However, as the Oxford English Corpus reveals, just a few things are predominantly described using a word from one family or the other: for instance, tiles are almost always ceramic tiles, and you will hear of only a ceramic artist; on the other hand, fragments found at archaeological sites are normally pottery shards, and the throwing wheel is only a potter’s wheel. If you want to describe all kinds of ceramic items, you would probably say ceramics rather than pots because many of the pieces will probably be figurative or decorative sculptures that are not even remotely like a pot.

This article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Featured Image: “hands spinning” by Regiane Tosatti. Public Domain via Pexels

The post The Great Pottery Throw Down and language appeared first on OUPblog.

Translating Shakespeare

Translation of Shakespeare’s works is almost as old as Shakespeare himself; the first German adaptations date from the early 17th century. And within Shakespeare’s plays, moments of translation create comic relief and heighten the awareness that communication is not a given. Translation also served as a metaphor for physical transformation or transportation. Claudius speaks of Hamlet’s “transformation” and asks Gertrude to “translate” Hamlet’s behaviour in the previous scene so that Claudius can “understand … the profound heaves”. Gertrude not only relays what Hamlet has just done but also provides her interpretations, as a translator would, of her son’s actions.

Henry V contains several instances of literal translation. The peace negotiations dictate that the English monarch marries the daughter of Charles VI of France, uniting the two kingdoms. The “broken English” in the light-hearted scene symbolises Henry V’s dominance over Catherine and France after the English victory at the Battle of Agincourt. One is unsure whether Catherine is speaking the truth that she does not understand English well enough (“I cannot tell”) or just being coy—playing Harry’s game, though Catherine eventually yields to Henry V’s request: “Dat is as it shall please de roi mon père”.

Given that Shakespeare used translated materials extensively, it is not a surprise that his plays are among the most frequently translated works today. Translating Shakespeare involves new semantic, semiotic, and cultural contexts. While European translators can draw on the shared Judeo-Christian and Greco-Roman traditions, the farther a language is situated from early modern English culture the more creative strategies of displacement a translator will have to deploy.

Translating Hamlet’s “to be or not to be” speech into Japanese, for example, will require substantial rewriting, because Japanese does not have the verb “to be” without semantic contexts. For the English sentence to make sense, the aphorism will have to be elaborated to specify what message the translator conveys and what values he betrays, but the punning value of the epigram will be lost.

In a collage of recitations of Hamlet’s “to be or not to be” speech in different languages, drawn from actual performances, the vague, versatile, and “Swiss-knife” verb “to be” is as ambiguous in English as it is in many other languages. Sometimes it is translated as “to have” (but to have or not to have what!?), to do, to die, and so on.

William Shakespeare by hiroaki maeda. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

William Shakespeare by hiroaki maeda. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.Working with Japanese, a language more complex than English from a sociolinguistic point of view, a translator would have to wrestle with more than 20 first- and second-person pronouns to maintain the ambiguity and subtlety of gender identities in a play such as Twelfth Night. In addition to making the right choice of employing the familiar or polite style based on the relation between the speaker and the addressee, the male and female speakers of Japanese are each confined to gender-specific personal pronouns at their disposal. Before a translation can be undertaken, decisions will have to be made on the register and gendered expressions to convey Orsino’s comments about love from a male perspective and Viola’s apology for a woman’s love when in disguise as Cesario in Twelfth Night, or the exchange between Rosalind in disguise as Ganymede and Oliver on her “lacking a man’s heart” when she swoons, nearly giving herself away.

But limitations create new opportunities and bring translation closer to an act of performative interpretation. Differences in grammatical structure aside, bawdy language and puns also pose a challenge. The exchange between Sampson and Gregory in Romeo and Juliet presents an opportunity for innovation and self-censorship:

Sampson: Tis all one, I will shew my selfe a tyrant, when

I haue fought with the men, I will be ciuil with the

maides, I will cut off their heads.

Gregorie: The heads of the maides.

Sampson: I the heads of the maides, or their maiden heads,

take it in what sense thou wilt.

Gregorie: They must take it in sense that feele it.

Sampson: Me they shall feele while I am able to stand,

and tis knowne I am a pretie peece of flesh.

Christoph Martin Wieland’s 1766 German version excised this scene in its entirety and begins with the encounter between Gregory, Sampson, Abraham, and Benvolio and the ensuing fight. Along similar lines, Goethe’s 1812 adaptation of the play (based on Schlegel’s verse translation) presents a sanitized version, turning Romeo from a volatile youth to a more responsible man. References to the lovers’ bodies are replaced by purified language. Juliet’s comment to her nurse that she will die “maiden-widowèd” because “death, not Romeo, take [her] maidenhead” (3.2.135-137) is rid of the reference to virginity. Cao Yu (1910-1996), an accomplished modern Chinese playwright, felt equally uncomfortable about the passage but approached the issue differently. Diverting the attention from maidenhead to the action of cutting off the head, Cao used the verb “gàn” to activate the latent connection between cutting off the maids’ heads and Samson’s later comment about his sexual prowess. “Gàn” has a very wide range of meanings from innocent daily usage to profanity, including to do, to get rid of, and to copulate.

Translations also shed new light on familiar Shakespearean passages. Consider for example these lines from Macbeth —

The multitudinous seas incarnadine,

Making the green one red.

The deliberate alternation between the Anglo-Saxon (Germanic) and the Latinate words suggests two pathways to and two perspectives on the world. The passage “translates” the words back and forth to draw attention to the color.

Act 1 Scene 3 of Othello offers another interesting instance (which is the focus of Tom Cheeseman’s multilingual crowd-sourcing project):

If virtue no delighted beauty lack,

Your son-in-law is far more fair than black.

Translations of these lines into different languages deal with the meanings of “fair” and “black” rather differently. Mikhail Lozinskij’s Russian translation says “Since honor is a source of light of virtue, / Then your son-in-law is light, and by no means black.” Christopher Martin Wieland and Ángel Luis Pujante used white in German and Spanish (respectively) to translate “fair,” while Victor Hugo chose “shining.” It’s eye opening to see how translation opens up the text in new ways.

Featured image: Timeless Books by Lin Kristensen. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Translating Shakespeare appeared first on OUPblog.

The power of imagination

Recently, Eddie S. Glaude has argued in Time magazine that the current US presidential campaign involves an attack on our imagination. “We must resist those voices who urge us to settle for the world as it is,” he writes. Rather, in line with political awakenings of the past, we must imagine what a better world would look like. In Glaude’s view, imagination is the key to our development of a better democracy — the key, for example, to achieving racial justice and economic equality.

Sure, imagination is powerful. But can it really change the world?

Indeed, it is tempting to answer “no” here — to disagree with Glaude about the transformative power of imagination. After all, imagination is the stuff of fancy, of fiction, of escape. We daydream to get away from the disappointing monotony of daily life, but no matter how fervently we imagine ourselves on a tropical beach, we’re still stuck at our desks staring at the blinking computer screens before us. And no matter how fervently children imagine themselves to be superheroes and ice queens and Jedi knights and mermaids, their imaginations will never be able to endow them with the superpowers that they lack. The snowmen they build aren’t going to talk to them, and the sticks they wave around are never going to turn into lightsabers.

But in fact I think Glaude is exactly right about the tremendous power of imagination. To see this — to see how imagination can indeed be a transformative tool in the betterment of ourselves and the society in which we live — we need to understand how imagination can be put to two different and seemingly incompatible uses. On the one hand there’s what we might call ‘the transcendent use‘ of the imagination. When we daydream in meetings, when we escape into a good book or movie, when children play games of pretend, they are using imagination to ‘transcend‘ the reality in which we live. But on the other hand there’s what we might call ‘the instructive use‘ of the imagination. When we use imagination for problem solving, for insight into the experiences of others, for exploration of the potentialities and possibilities that the future might hold, we are using imagination to ‘learn‘ about the reality in which we live. And it seems puzzling that one and the same mental capacity can be put to both of these uses: How can the very same mental capacity that enables us to escape from the world around us also teach us something about it?

Inspiration, by Hartwig HKD, CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr

Inspiration, by Hartwig HKD, CC BY-ND 2.0 via FlickrThe key is to recognize that our imaginings must be in some way tethered to the world in order for them to be useful to us. When we let our imagination fly completely free, it can be of use to us, but only in the transcendent sense. Rather, and perhaps somewhat paradoxically, our imagination can teach us the most only when it’s appropriately reined in.

When Olympic athletes were heading to compete in Sochi in 2014, it was widely reported that they used imaginative exercises to prepare for competition. One Canadian bobsledder reported that in the year leading up to the Sochi games he had mentally practiced the Sochi course hundreds of times. An American aerialist skier worked on her imagery techniques while sidelined with an injury and claimed that the work that she’d done in imagination helped her to return to competition a better jumper. But for any of this imaginative preparation to be at all useful, the athletes had to conform their imaginings to the facts about the courses they were going to run, to the actual twists and turns that they’d be facing.

Imagination has played an equally important role in other domains, but here too we see the necessity of aligning with real world facts. Albert Einstein credited much of his revolutionary scientific work to his imagination, and Nikola Tesla claimed to have mapped out all of the details of his inventions entirely in his imagination before ever putting pen to paper or doing any work in the lab. But for Einstein’s scientific theories to be accurate, and for Tesla’s inventions to work as they should, they could not ignore facts about the world. The gravitational constant is what it is, for example.

And the same holds true when imagining our political future. Martin Luther King had a dream, and it was a dream that forced people to look at our world quite differently from how they’d looked at it before, but it was a dream that was nonetheless a dream about the world in which we live. For the dream to come true we’d be forced to change, and to change dramatically, but the change was a possible one because it was anchored in basic facts about human nature, about our empathetic abilities that we were failing to exercise. It’s precisely this kind of imagining that can be most helpful to us. For imagination to change the world, it must be anchored in the world. How exactly to strike the delicate balance — how exactly to remain sufficiently anchored without being held hostage to the status quo — is an extremely difficult task, and it’s for precisely this reason that genuinely transformative imaginative vision is as rare as it is.

Rare, but not impossible – and as such, it’s certainly something to work towards. To make a better future, we do need imagination — but it can’t be imagination that’s completely unbridled. Yes, we need to dream big, and we need to be able to see beyond the state of the world as it is now. But that doesn’t mean we can let go of the world entirely. In dreaming big, we also need to be sure to dream smart.

Featured image credit: Open up to imagination, by Ryan Hickox, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The power of imagination appeared first on OUPblog.

March 18, 2016

Putting oral history on the map

Oral history has always been concerned with preserving the voices of the voiceless, and new technologies are enabling oral historians to preserve and present these memories in new and exciting ways. Audio projects can now turn to mapping software to connect oral histories with physical locations, bringing together voices and places.

In West Side Stories, developed by Oakland based production company Youth Radio, audio vignettes are placed on the map alongside neighborhood profiles and points of interest. The map is centered on some of the areas that have been hit hardest by gentrification, as home prices continue to climb in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Click on one icon and you can listen to interviews with people at an open house for sale, offering a front row seat to the changes in the neighborhood. The DeFremery Park icon plays a history of the area dictated by Black Panther Ericka Huggins, and includes a snippet of Angela Davis’s iconic Vietnam War speech. At the West Oakland Bart Station icon and you can read about turf dancing, a street dance commonly seen on the trains that ferry people between the East Bay and San Francisco. Below the text a video shows a handful of young people performing on the train, interspersed with snippets of dance lessons and local history.

The map layout makes the connections between these stories all the more clear. When listening to the open house story, you can’t help but notice that it is only a few blocks away from DeFremery Park and a number of interviews from people who are refusing to leave the neighborhood. The website offers a view of gentrification that is simultaneously broad and narrow, placing individual stories into the context of regional changes.

Another interactive website tracks stories of eviction across the San Francisco Bay Area, presenting more than a decade of change in the metropolitan area. According to its website, the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project is “a data-visualization, data analysis, and storytelling collective documenting the dispossession of San Francisco Bay Area residents in the wake of the Tech Boom 2.0.” The website’s Narratives of Displacement map shows the area flooded with a sea of red dots, each one representing a single eviction. Scattered across the map are links to edited oral history interviews with the people who have been evicted during the recent tech boom, as well as some who have successfully fought back.

Aside from oral histories, the project includes additional maps that provide invaluable context, bringing together census data, crime reports, and a list of the locally infamous tech company bus stops to more fully demonstrate the contours of displacement. While these other maps don’t link to the oral histories, they can help to place the individual stories within larger trends.

Finally, moving beyond the Bay Area, the Fiji Oral History Map aims to “reflect the diversity and expansiveness of the Fijian community worldwide and to provide a forum for members of the community to share their stories and connect globally.” The map includes written memories and recorded oral histories from the global Fijian community. As of this writing, the map only includes stories from the Australia, Fiji, and the United States, but by encouraging visitors to add their voices, it can continue to grow.

The map was developed in conjunction with a movie that uses a single family’s story to tell the complicated history of colonization in Fiji. The film’s trailer asks, “When you are born in a stolen land…Who are you?” This question guides both the film and the oral history project, as they attempt to give context to the Fijian community worldwide, allowing them to see themselves reflected in the past.

All three of these projects are deeply invested in preserving worlds that are either gone or quickly disappearing. In this way, they echo the goals – stated or implied – of many oral history projects. They each go even further, however, attempting to intervene in this disappearance, preserving not only the memories but also the worlds themselves. Youth Radio and the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project make it clear that they are fighting back against the silencing of their voices and the disappearance of their communities through gentrification and eviction. The Fiji Oral History Map is likewise fighting back against the silencing of Fijians through colonization. In their own way, each of these projects is working to create a digital space that holds open the possibility of returning to a physical space.

Image credit: You Are Here. By Tony Webster. CC BY 2.0 via diversey Flickr.

The post Putting oral history on the map appeared first on OUPblog.

11 films all aspiring medics need to see

Think the life of a doctor is dull? Think again! In a previous post, I recommended ten books by medical men which all doctors should read. Today, it’s the turn of medical movies. By focusing on the extremes of human life – birth, death, suffering, illness, and health – such films provide insight into the human condition and the part that we as doctors play in this never-ending theatre. Below are my top 11 film recommendations, which every aspiring (and indeed practicing) medic must see. Including psychiatric thrillers, emotional dramas, and the odd touch of comedy, the following viewing will prepare you for (almost) anything the ward may throw at you…

1. Ikiru (1952)

I start with a masterpiece by the giant of Japanese cinema: Akira Kurosawa. In his little known 1952 film Ikiru (“To live”), a bureaucrat dying of stomach cancer reflects on his life and changes his ways following diagnosis. The film depicts how not to break bad news (we are shown barium meal films with cancer) and the doctor not really communicating with the patient (now a central theme in medical education). The film is life affirming in spite of its sombre message – as following his diagnosis, the lead character pursues a thoroughly worthwhile task. Through his altruistic actions, he is finally fulfilled – reminding us all that death can be ultimately beautiful.

2. Red Beard (1965)

Cropped image of Satyajit Ray with Ravi Sankar music recording for Pather Panchali (1955). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Cropped image of Satyajit Ray with Ravi Sankar music recording for Pather Panchali (1955). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.In close contention for the top spot is Red Beard, also directed by Kurosawa. It depicts an arrogant young doctor who is dismayed he is given a posting in a small country clinic – instead of being a doctor to rich patients on qualification. He inevitably learns a lot from his new life however, thanks to his teacher ‘Red Beard’ (Dr Niide, played by Mifune, a stalwart in Kurosawa films), and the poorer patients he has to deal with. Our new doctor is taught compassion from his patients and realises that medicine is not about wealth or status. The film is based on a story by Shugoro Yamamoto, and Dostoevsky’s The Insulted and Injured.

3. Pather Panchali (1955)

In third place is a masterclass in cinema from Satyajit Ray’s debut film – Pather Panchali. The film depicts the hopes, aspirations, and ultimate dignity of the poor in a Bengali village, trying to get on with and better their lives. Poor access to nutrition, education, and health do not stop them from trying their best in adverse circumstances. The film also contains one of the most haunting depictions of death in cinema. The expression of the father as he discovers his young daughter has died – all accompanied by the shrieking of the sitar – depicts an unbearable loss better than words could ever express.

4. Cries and Whispers (1972)

This film was created by the Swedish director, Ingmar Bergman. I pick Cries and Whispers although Persona (1966) and The Silence (1963) could equally have been included – as well as the Seventh Seal (1957) and Wild Strawberries (1957). Cries and Whispers won out however, as a harrowing, emotionally draining film about a sister dying of cancer. She is watched on by her two sisters and a maid. Although the sisters are trying to comfort their sibling on her deathbed, the awkwardness of the situation and the distant emotions are so honestly displayed, that the viewer leaves feeling as if they have been in the room with the dying woman.

5. The Lost Weekend (1945)

Next is a film by Billy Wilder, The Lost Weekend. Wilder (the Austrian-born American film director) is probably better remembered for the comedy Some Like It Hot, and the film noir Double Indemnity. In The Lost Weekend, Ray Milland depicts the life of an alcoholic as never before, and the film remains one of the finest depictions of alcoholism – a condition which remains a major medical problem worldwide.

6. The Elephant Man (1980)

Qualcuno Volo’ Sul Nido del Cuculo (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest) by Cliff. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Qualcuno Volo’ Sul Nido del Cuculo (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest) by Cliff. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.The first of two picks involving disability – The Elephant Man was adapted from Sir Frederick Treves book. It was turned into a film by David Lynch in 1980, with John Hurt playing the elephant man himself, and Anthony Hopkins playing the London Hospital surgeon. The so-called “elephant man,” deformed as he was on the exterior, nevertheless had feelings and needs like any human – and the film illustrates the need to respect everyone’s dignity, irrespective of outer appearance.

7. The Men (1950)

On a similar theme of disability, we turn to Marlon Brando’s electrifying performance as a paraplegic World War Two veteran, in Fred Zinnemann’s The Men. The frustrations of getting used to paraplegia and being disabled has never been better depicted, or more emotionally rendered, in any cinematic production.

8. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

Viewed as one of the classic films of all time, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – directed by Milos Forman in 1975, and adapted from Ken Kesey’s brilliant book – will make one approach mental illness and institutions as never before. Jack Nicholson gave the performance of a lifetime as the anarchic R. P. McMurphy, and we begin to question who is normal and who is insane: a task which is not always easy for doctors.

9. An Enemy of the People (1978)

Whether the 1978 film of Ibsen’s play, with Steve McQueen in the lead, or the Satyajit Ray version (Ganashatru, 1989) – both illustrate how important it is to stick to your ethical beliefs. This dramatic story teaches young medics that ethics should not be compromised for anything. This is exemplified by the good doctor’s stance in the film, as ironically, he shifts to become the enemy.

10. The Doctor (1991)

A film that is used a lot for teaching students is The Doctor. It stars William Hurt as an arrogant surgeon, who develops throat cancer. It is only when he is treated as a patient that he develops empathy – and is changed forever by going through the process of sickness, healing, and ultimate redemption.

11. Doctor in the House (1954)

Finally, I include Doctor in the House, with Dirk Bogarde playing the medical student and young doctor. The film is a funny and nostalgic depiction of life in hospitals over 70 years ago, when arrogant surgeons like Sir Lancelot Spratt existed, and medical life seemed fun and relaxed – so distant to modern times!

Featured Image Credit: ‘Banner, Header, Film’ by geralt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post 11 films all aspiring medics need to see appeared first on OUPblog.

Special category states of India

There are eleven diverse hill states in India which comprise the group of “Special Category States.” They all suffer from the disadvantages that result from remoteness and geographical isolation, as well as historical and demographic circumstances. In addition to pathetic infrastructures, scant resources, unrealized human potential, and stymied economic growth, these states also represented various groups of marginalized minorities.

In order to address the issues facing these states, the Government of India accorded them each with a “special category status,” which was designed to solve their economic problems by allowing them liberal access to federal funds. The main problem with this solution was that is lacked any system of accountability. Even worse was that the unchecked flow of government resources was unlinked to any performance expectations in terms of the states’ growth.

Over time, several special category states developed to a capacity where they could use the federal funds for their intended purpose, and thus these states were able to improve themselves. Others could not do so for a multitude of reasons: some faced militant insurgency and political instability, others corruption, the lack of proper governance, and the absence of leadership.

As current states demand the same status, several questions arise concerning the nature, reality, and effectiveness of the “special category status.” Now, almost fifty years after the first Indian special category state was declared, we must consider the purpose behind their creation, the expectations while creating them, and whether they will permanently remain as special category states.

Featured image credit: Map ‘Prevailing Religions of the British Indian Empire’, 1909′ by John George Bartholomew. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Special category states of India appeared first on OUPblog.

The consequences of neglect

More than 70 years ago, psychologist Rene Spitz first described the detrimental effects of emotional neglect on children raised in institutions, and yet, today, over 7 million children are estimated to live in orphanages around the world. In many countries, particularly in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, the rate of institutionalization of poor, orphaned, and neglected children has actually increased in recent years, according to UNICEF.

Meanwhile, evidence documenting the negative consequences of institutionalization on children’s minds and brains continues to mount. One of the most scientifically rigorous studies comparing the effects of orphanage versus home rearing is the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Researchers randomly assigned orphaned Romanian infants and toddlers either to institutional care—which is the norm of care for orphaned children in Romania—or to high-quality foster parents who were thoroughly vetted and trained by the researchers. Because the children were drawn from the same population and randomly assigned to groups, any group differences in outcomes must logically be due to the different forms of care to which the children were assigned.

Early studies from this research group focused on cognitive and emotional outcomes in children in the institutional versus family-based foster care setting. The children raised in family settings developed higher IQs than those who stayed in orphanages, an effect that held true over an eight-year follow-up period. Children placed in foster care subsequently had better language development than those who remained in orphanages. They exhibited more secure attachment to caregivers than those left behind in orphanages, and they developed fewer signs of emotional problems. Critically, for virtually all of the outcomes, the benefits of family care were realized primarily for those children who were placed in families before the age of two. Early placement in stable families is clearly better for children.

Institutional rearing negatively impacts children’s biology, as consistently shown by studies from the Bucharest project. Children left in institutions have altered stress physiology, including abnormal stress-hormone responses during challenging tasks in a laboratory setting. Compared to children who were assigned to foster care, institutionalized children have more abnormalities in the white matter structure of the brain, which refers to the fiber pathways that facilitate communication between brain regions. They have blunted brain responses to pictures of faces. They exhibit atypical patterns of oscillatory activity in the electroencephalogram, the measurement of electrical activity in the brain.

Even chromosomes inside the cells of the body are affected by institutionalization. Telomeres are protective portions on the ends of strands of DNA, and they are known to diminish with normal aging. High levels of chronic stress have been associated with greater diminishment of telomeres, suggesting that stress speeds aging at the cellular level. A study from the Bucharest project found that telomere shortening in Romanian children was directly related to the amount of time spent in an orphanage. The adversity of orphanage rearing leads to faster cellular aging.

Some children are affected more than others by the social-emotional deprivation of institutional care, and researchers, child-welfare professionals, and parents have long wondered why. Although many factors are likely at play, some evidence suggests a contribution from genetics. Children who carry two copies of a particular gene (one that affects the brain’s serotonin neurotransmitter system) are differentially susceptible to the impact of early caregiving environments. These children both benefit more from family-home rearing and suffer more from institutional rearing, compared to children with other genotypes. For these “sensitive” children—whose genotype is fairly common in the general population—the caregiving environment has a particularly profound impact, pushing the children in either a positive or negative direction depending on whether the environment is enriching or depriving. Needless to say, we can’t change children’s genes, but there is at least a possibility of changing their environments.

Given the extraordinary amount of evidence that institutionalization is damaging to children, why does it still happen? There is a startling disconnect between the scientific evidence and child welfare practices in many places in the world. Political and cultural concerns can trump science, as is the case in Russia, for example, which maintains an extensive system of state-run orphanages. Such institutions provide jobs and graft for bureaucrats and are therefore resistant to dismantling. Domestic adoption is culturally stigmatized in Russia, which has also banned most international adoption for nationalistic reasons. Little social support exists for raising children with disabilities, who face particularly heartbreaking conditions in orphanages. Russian families continue to feel the sting of a faltering economy as well as high rates of alcoholism and reduced life expectancy, undermining attempts to find adequate foster families or to support birth families so that children are not sent to institutions in the first place. Data indicate a disturbingly high rate of fostered and domestically adopted children being returned to orphanages in Russia. Elsewhere in Eastern Europe, such as in Romania and Ukraine, strides have been made to support domestic adoption, but cultural norms are difficult to change, and institutionalization persists. Sadly, unless some of these factors are addressed with urgency, marginalized children will carry the scars into the next generation.

Featured image credit: Rebecca Compton

The post The consequences of neglect appeared first on OUPblog.

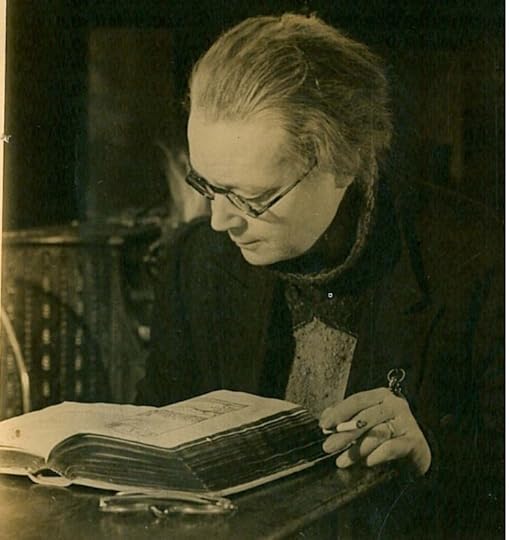

The trick of the lock: Dorothy L. Sayers and the invention of the voice print

Pre-eminent among writers of mystery stories is, in my opinion, Dorothy L. Sayers. She is ingenious, witty, original – and scientific too, including themes like the fourth dimension, electroplating, and the acoustics of bells in some of her best stories. She is also the inventor of the voice-activated lock, which her hero Lord Peter Wimsey deploys in the 1928 short story ‘The Adventurous Exploit of the Cave of Ali Baba’ (in the collection Lord Peter Views the Body). To find out the role the device plays in the unraveling of a crime, you’ll have to read the story, but this is how Peter describes the invention:

“… you see, it’s one of these new-style electric doors. In fact, it’s really the very latest thing in doors. I’m rather proud of it. It opens to the words “Open Sesame” all right – but to my voice only.”

Dorothy L. Sayers at her work. Image used with permission via the The Dorothy L Sayers Society.

Dorothy L. Sayers at her work. Image used with permission via the The Dorothy L Sayers Society.Voice-operated locks do now exist (even for your smartphone, should you so wish), though many are no more reliable than Wimsey’s:

“… to be rather pernickety about voices. It got stuck for a week once, when I had a cold and could only implore it in a hoarse whisper. Even in the ordinary way, I sometimes have to try several times before I hit on the exact right intonation.”

Today’s locks (sometimes called voice print systems) rely entirely on computers, programmed with pattern-matching software. This software compares the frequency pattern of a fresh-spoken word with the reference versions in its library, making allowances for acceptable levels of variation in the pronunciation of that word. If there is a close enough match, the software is satisfied and the lock opens.

On the face of it then, Sayers’ machine is pure whimsy in 1928, two decades before even the most primitive computers were built. It was not until 1952 that the first (sort of) working voice-activated system was constructed, by Bell labs. Called ‘Audrey’, it could recognise digits, if spoken carefully by the correct person. ‘Audrey’ was an electronic system, built using the then newly-invented transistor. Trying to build a 1928 version would have meant using valves and ending up with something big enough to fill a small room, with a slightly room full of noisy air-conditioning equipment to cool it, and a vast electricity bill.

Is Sayers daunted by the challenge? Does she pass over the awkward details in silence, drown them in technobabble or distract the reader with a sudden gunfight? She does not, explaining instead that her invention includes, “… a microphone arrangement [which] converts the sound into a series of vibrations controlling an electric needle. When the needle has traced the correct pattern, the circuit is completed and the door opens.”

Cover of Sayer’s book Whose Body?, published in 1923. Public domain via Project Gutenberg.

Cover of Sayer’s book Whose Body?, published in 1923. Public domain via Project Gutenberg.The device, then, is based on the gramophone, a very popular device of the time, in which songs were recorded by being sung into a microphone that converted them into the motions of a needle. The needle in turn scratched the soft surface of a rotating wax disc (such discs had only just replaced cylinders as the main recording medium). The needle was moved gradually in towards the centre of the disc so that instead of moving in a circle it made one long spiral groove.

Once hardened the recorded disc was rotated again, at the same speed as before, with a second needle fitted into the groove. The wobbles of the groove forced the needle to wobble too, and those wobbles were converted by a loudspeaker into sound once more. Considering how primitive this all sounds, the quality of the result was astounding. Could the system really be used to make a voice-activated lock? Certainly, it would be easy to make a recording of Wimsey saying “Open Sesame” on a disc (the “master”). But then what happened?

To prime the system, Wimsey would place the master on a turntable inside the room to which the voice lock gave access. He would rest a needle in the groove, retire and close the door, which would be fitted with a spring bolt that could be drawn back again by means of an electromagnet.

To gain entry, Wimsey would say “Open Sesame” in exactly the same way he did when he recorded the master. The microphone would transmit the vibrations of his voice to the needle, just as it would if its function were to make a new recording. However, since the master had already been used and hardened, the needle could make no impression on it. Instead it would trace anew the wobbles of the groove already inscribed on it. This might be like an ice-skater negotiating a narrow twisting path with fences on either side: only by following the curves of the path exactly could (s)he avoid crashing into the fences.

Thomas Edison and his early phonograph, 1878. Cropped from Library of Congress copy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Thomas Edison and his early phonograph, 1878. Cropped from Library of Congress copy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.If someone other than Wimsey said “Open Sesame”, the path traced by the needle would not be the same as that on the disc, and the needle would run into the side of the groove and jump out. Only if the spoken and recorded versions were identical would the needle trace the entire groove, at the end of which it could open the lock by completing an electrical circuit, allowing electricity to flow through the electromagnet, which would then withdraw the bolt.

There are several practical problems to be overcome here – in particular how to start the master rotating at the right moment so that it was synchronised exactly with Wimsey’s voice, but this could be overcome, perhaps, by means of pressing a button as he started to speak. A more fundamental problem is the one which has bedevilled the builders of voice-operated systems since they were first invented and which still persists to some extent today: it is almost impossible to say the same word in the same way on a different occasion twice. Sayers hits the nail on the head here when referring to Wimsey’s cold, but the system as described above would be so sensitive that it would pick up the slightest variation – in anything! If the word were spoken fractionally faster, slower, higher or lower, that would be enough for the system to reject it. Nevertheless, the principle is sound – in fact, it’s really brilliant, and apparently entirely Sayers’ own.

What might have suggested such a novel invention to her? The changing world of popular music at the time might be a clue. Until the early 1920s, recordings on cylinders and discs were a great success, despite their fragility, speedy deterioration and distinctly lo-if performance. Everyone either had, or wanted, a gramophone. Some were even portable! But as the decade moved on, radios rapidly improved in performance and fell in price, and soon eclipsed gramophones as every household’s must-have item. Some gramophone manufacturers and recording companies went bust and those that survived did so by improving the quality of their recordings enormously. By 1928 – the year of ‘The Cave of Ali Baba’- disc recordings were able to reproduce sounds almost perfectly (even by 1924 they were so good that, in writing his symphonic poem The Pines of Rome, Ottorino Respighi felt confident in including a gramophone record of a nightingale’s song in the third movement, something which would have been unthinkable just a few years previously). So perhaps it was this apparently boundless improvement in gramophone technology that inspired Sayers to press it into service in her fiction. If so, it’s just as well she wrote the story when she did – the very next year, stock markets crashed and the great depression that followed knocked the bottom out of the gramophone market, and left it floundering for years to come.

Featured image credit: Gramophone, by AlexVan. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post The trick of the lock: Dorothy L. Sayers and the invention of the voice print appeared first on OUPblog.

March 17, 2016

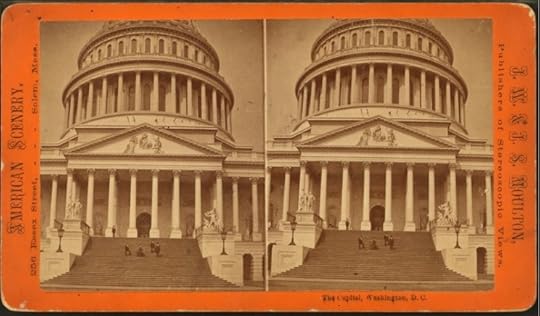

Washington D.C. civil rights slideshow

Brown v. Board of Education is one of the most identifiable civil rights cases in our nation’s history. While most scholarship begins with this case, Just Another Southern Town by Joan Quigley recounts the battle for civil rights beginning with the case of District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Co. In this slideshow, Joan Quigley weaves together the success of this case with other landmark civil rights moments in Washington, DC, creating a timeline of the struggle for racial justice in our nation’s capital.

April 16, 1862

President Abraham Lincoln signs the District of Columbia Emancipation Act, which frees 3,100 slaves in Washington, nine months before the Emancipation Proclamation liberates slaves in the Confederacy.

Image Credit: Abraham Lincoln by Brooklyn Museum. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

1867 - 1878

Congress has jurisdiction over Washington under the Constitution. In 1867, during postwar reconstruction, Congress grants suffrage to the capital’s black men (a privilege white males already enjoyed). Between 1869 and 1873, local Washington legislators pass a series of antidiscrimination laws. The measures ban discrimination in public accommodations in the capital, including restaurants. By 1878, Congress has disfranchised all Washington voters – black and white – and dismantled the city’s local government, installing three presidentially appointed commissioners.

Image Credit: The Capitol, Washington, D.C. by J.W. & J.S. Moulton. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

July 1896

At a national convention of African American women in Washington, the National Association of Colored Women forms. Mary Church Terrell is elected its first president.

Image Credit: Before graduating from Oberlin College in 1884, Mary Church posed for a portrait in a local studio. Neither of her parents attended her graduation ceremony. Courtesy of the Oberlin College Archives.

1913

The administration of President Woodrow Wilson segregates federal employees.

Image Credit: Woodrow Wilson at his desk in the Oval Office by Library of Congress. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

May 30, 1922

Chief Justice (and former President) William Howard Taft presides over the dedication ceremony for the Lincoln Memorial. Also in attendance are President Warren G. Harding and Robert T. Lincoln, the son of the former president. African American guests are assigned to a segregated seating area. About 20 of them walk out in protest.

Image Credit: Taft, Harding, Robert, Lincoln by National Photo Company. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

April 9, 1939

On Easter Sunday, Marian Anderson, the African American contralto, performs a free twilight concert at the Lincoln Memorial. Her performance was arranged after the Daughters of the American Revolution denied her access to Constitution Hall because of her race.

Image Credit: Marian Anderson, Lincoln Memorial by U.S. Information Agency. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

January 27, 1950

Thompson’s Restaurant, a cafeteria located a few blocks from the White House, refuses to serve 86-year-old Mary Church Terrell and two of her colleagues because they are “colored.” She takes the matter to court, seeking to enforce Washington’s Reconstruction-era antidiscrimination laws. During his annual State of the Union address three weeks earlier, on January 4, 1950, President Harry S. Truman had promised to support federal civil rights legislation – a pledge he first made in 1948.

Image Credit: President Truman delivering his State of the Union Address to joint session Congress by U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

February 2, 1953

In his first State of the Union Address, President Dwight D. Eisenhower vows to end segregation in Washington, D.C. He receives tepid applause.

Image Credit: Dwight D. Eidenhower by U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

June 8, 1953

The U.S. Supreme Court unveils a unanimous decision in District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Co., Inc., invalidating segregation in Washington restaurants. Justice William O. Douglas writes the opinion for the Court. The justices also schedule Brown v. Board of Education and four companion cases, including one that arose in Washington, for a second round of oral argument in the fall.

Image Credit: Justice William O Douglas by Library of Congress. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

May 17, 1954

The Supreme Court releases its unanimous Brown decision, invalidating school segregation. A separate opinion, Bolling v. Sharpe, strikes down segregated public schools in Washington.

Image Credit: Warren Court 1953 by United Press International telephoto. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Feature Image: US Capitol Building by FSP Vintage Collection. Public Doman via Free Stock Photos.

The post Washington D.C. civil rights slideshow appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers