Oxford University Press's Blog, page 531

March 24, 2016

Cambiata choirs explained

At the beginning of May 2015, I spent some time at the Cornwall International Male Voice Choral Festival, a massive affair with 70 choirs at 60 events in 50 venues all over Cornwall, packed into a long Bank Holiday Weekend. The mastermind behind this well-organised event was Festival Director Peter Davies, director of the Huntingdon Male Voice Choir. Over the 25 years or so that I’ve known him, he has worked hard, alongside many other colleagues, to encourage the development of the male voice choir tradition into a vibrant and forward-looking movement with a range of choirs, styles, and approaches with a wide appeal.

Thirty years ago, such a festival would consist of a number of rather similar looking choirs, gentlemen of a certain age with matching blazers and ties, singing, from memory, largely homophonic (chordal) music, often inspired by hymn-tunes or folk-songs, and attempting a wide dynamic range, from a whisper to a rousing forte, with varying tonal control. Last week, in the two concerts and the competition that I attended I could still hear that tradition – but there was also a flourishing youth presence, with choirs not only from all over the UK but from St Petersburg, and adult choirs from a similarly wide range of places including Estonia and the Czech Republic. The style of music, too, was much more varied. There were some traditional male voice choirs, from Cornwall, Wales, and elsewhere, fervently singing the classic music of their genre with excellent blend, communication, and wide dynamic range, but alongside that there were jaunty barbershop choirs, small ensembles that skilfully combined comedy with artistic and characterful singing, boys choirs singing a good range of arrangements and original songs with great stage presence, and – the main reason I was there – cambiata choirs.

Courtesy of Martin Ashley.

Courtesy of Martin Ashley.If you’ve not come across this rather odd term, a cambiata choir is for adolescent boys whose voices are changing (we don’t refer to ‘breaking voices’ any more) – and they are designed to encourage teenagers to keep singing by performing music which has been specially arranged or written for them. There has been much research into this in the US and the UK (for example by Martin Ashley, author of the recent book Singing in the Lower Secondary School), and a standard format for cambiata pieces is developing — written in several parts, each of which cover a quite narrow but overlapping pitch range, so that voices are not strained or over-stretched at this important point in their development. Although, of course, there have always been choirs involving this age-range, those with changing voices have tended to be side-lined, and this movement is designed to put such voices centre stage.

I was privileged to be offered 2015’s Festival commission – and it, was, for the first time, to be for cambiata choir. My initial difficulty was to find an appropriate text – a recurring concern for the choral composer, but for teenage boys in particular there are many no-go areas. So I hit on the idea of those many warning notices to be found – on packaged food, children’s toys, railway trains, and on the instructions that came with my new printer. And thus my suite of three short songs for cambiata choir and piano was born. (Health and Safety will be published by OUP in the summer of 2016.)

Let’s hope that many more cambiata choirs will develop in the future, and that more music is written and arranged for them.

A version of this article originally appeared on Alan Bullard’s blog.

The post Cambiata choirs explained appeared first on OUPblog.

Art of the Ice Age [slideshow]

In 2003 Paul Bahn led the team that discovered the first Ice Age cave art at Creswell Crags in Britain. In recent years, many more discoveries have been made including the expanding phenomenon of ‘open-air Ice Age art’. Information gathered from advanced dating methods have revolutionized our knowledge of how cave art was created and when it was created. For instance, we now know that the art found at Creswell Crags must have been created at least 12,800 years ago. This may seem like a long time ago, but other examples of cave art date back 40,000 years.

In the slideshow below, you can see some of the earliest examples of art on the planet, and take a tour of prehistoric art throughout the world.

Mammoth

Mammoth, c.10 cm long, engraved on a fragment of megafauna bone, Vero Beach (Florida), date unknown. When first revealed a few years ago, it was widely suspected to be a fake, but microscopic and chemical analyses have not been able to challenge its authenticity.

Photo courtesy of P. Bahn.

Small red human stick figures

Small red human stick figures exposed on the back wall of Toca do Baixão do Perna rock-shelter, Brazil, by excavation of the layers which had covered it. Though faded, the images survived burial amazingly well. One fragment of charcoal still adhering to the panel gave a radiocarbon date of 9650 years ago, while charcoal from the layer touching the bottom of the panel has been dated to 10,530 years ago — hence, unless one envisages artists painting at nose level while lying on the floor, the panel must be somewhat older than this date.

Photo courtesy of P. Bahn.

Handaxe

This handaxe, c.13.5 cm long, found in 1911 at West Tofts in Norfolk, England, and probably several hundred thousand years old, was carefully made so as to preserve a fossil shell of Spondylus spinosus at its centre, indicating the existence of a keen aesthetic sense at this time.

Photo courtesy of P. Bahn collection.

Aurochs petroglyphs at Qurta, Egypt

One of the most important new developments of recent years has been the discovery that open-air Ice Age pecked and engraved figures can survive in certain environments — not only in Europe but also in Egypt, particularly at Qurta, in the Edfu region — where pecked images of aurochs, hippos, fish and birds have been found, as well as some Gönnersdorf-style females. OSL dating of sediments covering some petroglyphs at Qurta has proved that they have a minimum age of 15,000 years. These discoveries triggered searches elsewhere, and rapidly led to new similar finds, for example in the Aswan region.

Photo courtesy of P. Bahn.

Horse from Vogelherd, Germany

The horse from Vogelherd, Germany, carved from mammoth ivory. Less than 5 cm in length, it is widely thought to date to the Aurignacian period (i.e. more than 30,000 years ago), but in fact the site was dug badly, many years ago, so its portable art objects may be more recent, although still of the Ice Age.

Photo A. Marshack, and courtesy of the P. Bahn collection.

Horse-head carved in limestone

Horse-head carved in limestone, from Duruthy (Landes). Magdalenian. Length: 7.1 cm, height: 6.2 cm. This Pyrenean rock-shelter contained a series of horse carvings in a kind of ‘horse sanctuary’ dated to the 14th millennium bp; the biggest, a kneeling sandstone figure, rested against two horse skulls and on fragments of horse-jaw, while three horse-head pendants were in the immediate vicinity.

Photo courtesy of P. Bahn.

Featured image credit: Rock painted panel with figures of bison in the cave of La Covaciella, Spain by Locutus Borg. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Art of the Ice Age [slideshow] appeared first on OUPblog.

March 23, 2016

‘Vulpes vulpes,’ or foxes have holes. Part 2

Last week, I discussed the role of taboo in naming animals, a phenomenon that often makes a search for origins difficult or even impossible. Still another factor of the same type is the presence of migratory words. The people of one locality may have feared, hunted, or coexisted in peace with a certain animal for centuries. They, naturally, call it something. Later their neighbors, who are less familiar with the creature, borrow the name and pass it on to their neighbors, and so it goes. Once the word becomes common property, nobody remembers the center of its dissemination. At least one of the names relevant to the subject in hand makes us think of “migration.” The Old Icelandic for “fox” (mentioned last week) was refr. Although outside Scandinavia the word does not occur, it is usually traced to an ancient Indo-European root meaning “shining” (the implication is “a red animal”: see below!). But the Finnish for “fox” is repo, nearly the same word, so that refr could have been a borrowing, whatever the direction. To make matters worse, we find Spanish and Portuguese raposa, Ossetian rubas ~ robas, and so forth (so forth means Greek and Sanskrit). Most likely, the animal’s name “migrated” with fur trade. However, this hypothesis does not account for the word’s etymology, because somewhere it had to be native. Perhaps refr does have the Indo-European root that means “shining,” but we will hardly ever know the truth.

The only thing about the origin of fox that does not cause disagreement is its grammatical gender. Fox is really fok-s, whose characteristic ending s shows that the word is masculine, and indeed, Old High German foha and Old Icelandic fóa have preserved the feminine form. It is curious that the medieval Scandinavians had fóa (which, incidentally, did not always designate the vixen) and still needed refr. We also know the Gothic word for “fox”: it was fauho (read au as short o in Engl. fox), masculine. The craftiness of the fox is connected with female charms and sorcery all over the world. Likewise, Slavic lisa (feminine) is the main representative of the species. Reineke ~ Reynard is a male only because he is a member of the king’s retinue, but in folklore the fox is nearly always a she.

A portrait of the fox as a young beast

A portrait of the fox as a young beastIf we assume that Latin vulpes represents with some accuracy the ancient Indo-European name of the fox, then the more or less similar forms elsewhere may be taboo alterations of the basic word, with Germanic refr and foh-a ~ fok-s being complete replacements of it. The repertory of taboo variants for the fox in the languages of the world (in so far as we can decipher them) is not rich. The animal is usually called “a long-tail,” “a bushy tail,” “red,” and “stinker.” Surprisingly, as mentioned in Part 1, “sly,” the especially prominent feature of the fox in popular culture, never shows up in that list.

The most often expressed opinion connects fox with Sanskrit púcchas “tail”; for comparison: northern Engl. tod means both “tail” and “fox.” An alternative etymology points to Russian pukh “down, fuzz.” The two p-words are related, so that we are dealing with the same root. However, the meanings are different; calling an animal a beast with a long tail is not the same as calling it furry. The chance of the relationship between fox and either púcchas or pukh is rather high, and this is what I meant when last time I said that fox, even though it does looks like a taboo word, still seems to have a respectable Indo-European etymology. I’ll skip several other conjectures that strike me as improbable or even fanciful.

Fee-fi-fo-fum, or being able to identify a particular smell.

Fee-fi-fo-fum, or being able to identify a particular smell.Before going on, I have to tell a short story. In the days of old street cars (like the one named Desire), a little girl asked her mother how that vehicle moves. The woman gave her daughter a detailed explanation about wires, rails, and electricity. The girl listened patiently and said: “No, this is not the way it goes.” “And how does it go?” wondered the mother. “Ding-dong” answered the girl. The next hypothesis about the origin of fox is of the ding-dong kind. Not long ago, a German scholar noted that one of the most common interjections expressing disgust is fu ~ foo. Compare fee-fie-fo-fum/ I smell [!] the blood of an Englishman, Shakespeare’s favorite fie, and the interjection phooey. Artur Kutzelnigg, the German linguist who published a short article on fox (1980), gave no English examples, but his conclusion did not depend on English. According to him, fox got its name from the interjection fuh! or buh!, or puh! Perhaps it did. If so, then all the learned suggestions about Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, and Proto-Germanic turn into some sort of ding-dong. Elmar Seebold was so impressed by Kitzelnigg’s idea that he mentioned it in his edition of Kluge’s German etymological dictionary.

In dealing with the history of fox, we should take into account another complicating circumstance. Quite often the same word designates more than a single animal. Thus, the fox occasionally shares its name with the wolf, the jackal, and even the dog. The Indo-European name of the fox, the one that resembles Latin vulpes, is almost indistinguishable from Germanic wolf; nor is Latin lupus too far behind. One can imagine some term like “tearer,” “cattle thief,” “pest,” or even “enemy,” with later more or less arbitrary specialization. It does not seem to be the case with fox; yet this factor should not be forgotten.

A streetcar named etymology: Ding-dong

A streetcar named etymology: Ding-dongSo where are we with fox? Fox is not the original Indo-European name of vulpes vulpes. In Germanic, that name has been retained in wolf. Fox is a taboo replacement of the ancient word, perhaps with reference to its fur or tail. The fou-fou idea strikes me as less probable but not impossible. Etymological statements, as I have said more than once, are not theorems: they cannot be proved with reference to a set of postulates; everything in them is based on probabilities, not certainties. Despite Gothic fauho, the original gender of fox seems to have been feminine; if so, fok-s is a later development. In folklore, the stinky beast acquired almost demonic features. Those interested in seeing how even the fox can be outwitted are advised to reread Brer Rabbit’s war with Brer Fox. The famous adventure in the thorn bush is a good place to begin: it will remind the readers how thorny the science of etymology sometimes is, but it will also inspire hope, for Brer Rabbit extricated himself from the bush, escaped his enemy, and thus outfoxed the fox.

Compounds with fox are rather numerous. Two of them have caused controversy. One is the flower name foxglove. Yes, it is indeed fox- not folk’s glove. It is amazing how much has been written about this word and what big guns participated in the battle. Foxfire is less clear. At least one Celtologist, arguing from his material, insists on the connection between foxfire and fox, while Romance scholars sometimes think of Old French fos “fool,” since foxfire, that phosphorescent light, means something deceptive or deluding and is not called ignis fatuus for nothing. Anyway, nowadays Firefox is much better known than foxfire. Finally, if someone can explain why in Irish English foxed means or meant “drunk” (there also is or was the idiom to catch the fox “to get drunk”), I’ll be most grateful for the explanation.

Image credits: (1) Yawning red fox. Photo by Peter G Trimming. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Jack and the Beanstalk Giant. English Fairy Tales (1918), by Flora Annie Steel, Illustrated by Arthur Rackham, The Project Gutenberg eBook. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Streetcars – getting on Broadway car, July 11, 1913. Public domain via George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress.

The post ‘Vulpes vulpes,’ or foxes have holes. Part 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

Sleepy Hollow’s Apocalypse

“The answers are in Washington’s Bible!” Katrina shouts as Moloch stirs the dark, swirling clouds that will seal her once again in Purgatory. Her husband, Ichabod Crane, stands watching, unable to help as his wife is swallowed up in a world that he can only reach in dreams and visions. Ichabod has been resurrected from the dead in the twenty-first century and faces Death himself in the form of the headless horseman of Sleepy Hollow. With the help of officer Abigail Mills, he pieces together what has happened, and what will be happening, in a quiet town on the Hudson River in upstate New York. This isn’t exactly how Washington Irving told the story, but the tale has engrossed dedicated television viewers for three seasons now on the Fox network.

Noting that Fox has shifted Sleepy Hollow to the dreaded Friday night slot against other networks’ supernatural-themed programs, Cinemablend has predicted the third season of the cult success will likely be its last. As a perhaps premature retrospective, I would like to consider the role of the Bible in the series. This isn’t gratuitous Bible-grubbing, the very premise of the first season was biblical in every sense of the word.

A brief summary will help. Ichabod Crane, envisioned in this telling as a former Oxford University professor of languages, is a captain in the colonial army during the US Revolutionary War. Killed in battle by a Hessian mercenary, he beheads his attacker in his dying moments. His wife Katrina (née van Tassel) preserves Ichabod by burying him with George Washington’s Bible on his chest. She’s a Quaker who also happens to be a witch. In the present day, Ichabod reawakens only to be completely confounded by the technological age into which he emerges. Abigail Mills (Abbie), a police lieutenant, reluctantly comes to believe him when he claims to be two centuries old and pursued by a headless ghost. That’s the basic plot.

Here’s the biblical part: the headless horseman is Death, the fourth horseman of the Apocalypse. Also, Ichabod and Abbie are the two witnesses cited in Revelation 11.3. This is the end of days.

As if that’s not enough biblical backstory, Ichabod and Abbie attempt to stop the horseman, time and again, by returning to George Washington’s Bible. Each week a new scary monster emerges as Sleepy Hollow inexorably nears the coming cataclysm. The Bible they consult is replete with woodcuts depicting the apocalypse and, as season one unfolds, hidden messages in the text of the Bible itself. It’s fair to say that without the Bible, the plot of first season wouldn’t have had any narrative glue.

Moloch is the demonic architect of this unrelenting attack on the town. Moloch, in origin, is a “foreign god” known from the Bible (primarily in Leviticus and the books of Kings). In Sleepy Hollow, he stands in for the Devil, reigning over Purgatory and planning to take the world by force through unleashing the four horsemen. Death and War, two of the four, emerge.

At key points during the first season, the Bible saves the day. For example, a golem arises to attack Sleepy Hollow. Only by consulting Washington’s Bible does Ichabod come to understand the nature of the monster and the means for stopping it.

As the first season builds to its climax, the Bible becomes even more central to the plot. Moloch wants to get his hands on Washington’s Bible. He sends a demon to possess the police captain’s daughter, holding her as ransom. The Bible is important not because it’s the Bible, but because it’s Washington’s Bible. The first president left clues in the book that will allow Ichabod and Abbie to release Katrina Crane from Purgatory to take on Moloch. Some of the clues are in disappearing ink while others are extra verses added to the biblical text. Season one ends with Purgatory opened and the horsemen Death and War ready to ride.

Season two, however, shifts the focus. In spinning the plot out further, eventually the Apocalypse is downgraded, and the Bible virtually disappears from the series. Moloch is killed. Ichabod and Abbie question their role as witnesses and whether their job is complete. Monsters still appear, but they are no longer biblical. The premise underlying season one has been lost.

Due to less-than-stellar ratings, Sleepy Hollow has been shifted to undesirable viewing slots during its third season. It’s perhaps tempting to suggest that the move away from a biblical story-line might have something to do with declining interest, but that’s not really a fair assessment. Far more likely is that the series faces the dilemma of where to go once the initial antagonist is killed off. In this case, the antagonist happened to be firmly biblical. The world won’t end after all. Without the Apocalypse to avoid, viewers will naturally seek a more pertinent thrill.

Featured image credit: “The Headless Horseman Pursuing Ichabod Crane” by John Quidor. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Sleepy Hollow’s Apocalypse appeared first on OUPblog.

Taking race out of human genetics and memetics: We can’t achieve one without achieving the other

Acknowledging that they are certainly not the first to do so, four scientists, Michael Yudell, Dorothy Roberts, Rob Desalle, and Sarah Tishkoff recently called for the phasing out of the use of the concept/term “race” in biological science.

Because race is an irredeemably nebulous, confused, and confusing social construct, the authors advocate for replacing it with “ancestry.” “Ancestry,” they say, is a “process-based” concept that encourages one to seek information about genomic heritage, while race is a “patternbased” concept that induces one to organize individuals into preconceived hierarchical groupings based on shifting, murky, and contradictory combinations of appearance, geography, ability, worth, and the like.

If biological science seeks and relies on valid and maximally precise population level comparisons between groups, and race is an irrefutably imprecise proxy for consistent and concordant biological/genetic comparison, then of course we should stop using it in biology and switch over to “ancestry,” “genetic heritage,” or some other term that actually gets at what’s real, reliable, and useful. It doesn’t feel like a rocket-science proposition. And yet biological science hasn’t been able to heed the call and make the shift. And I sadly forecast that the shift won’t soon – or ever – be made – unless and until we take the step that even the well-meaning authors of this call for stop short of taking.

Yudell, Roberts, DeSalle, and Tishkoff state the following in their penultimate paragraph:

Phasing out racial terminology in biological sciences would send an important message to scientists and the public alike. Historical racial categories that are treated as natural and infused with notions of superiority and inferiority have no place in biology. We acknowledge that using race as a political or social category to study racism and its biological effects, although fraught with challenges, remains necessary. Such research is important to understanding how structural inequities and discrimination produce health disparities in socioculturally defined groups.

This proviso amounts to a recapitulation of a different but equally harmful form of the very problem that the brave authors are trying to solve. It is as if while making vigorous efforts to steer away from the Scylla of specious race science, they are unaware that they have been sucked headlong into the Charybdis of spurious race psychology. After all, biologist who might want to preserve the use of race as a proxy for population difference would likely echo what Yudell et al provide as their reason for maintaining race in the realm of social science, that is that despite its problematic nature, race is important to understanding how conventional social identity constructs manifest in terms of unequal effects, including biological ones (the “race is problematic but as yet indispensible” resignation).

The same critical insight the authors provide as reason to steer away from the use of race in biological science must be applied to the use of race in social science. And the same solution of replacing the language of race with better language in the realm of biology must be applied to the use of race in the social sciences.

In Richard Dawkins’ 1978 book, The Selfish Gene, he introduced the concept of a “meme,” the cultural equivalent of a gene. Memes are simply ideas that rise or fall, flourish or perish, depending on their ability to fit into (adapt to) the zeitgeist into which they are introduced. Race is one of the most virally fecund memes to ever have emerged in the cultural “meme pool” of human ideas – not merely fitting in, but actually reshaping its environment to support its propagation. Its rootedness in the human imagination has achieved the status of a natural and permanent aspect of the human condition. So much so, that most people, including the authors cannot see the way beyond it.

The way to safely and effectively move beyond both the Scylla of biological race and the Charybdis of psychosociological race is to apply the ameliorative force of alternative language to both sides of the racial straits. In the same way that the authors advocate that we must disabuse ourselves of the false notion that there is biological race, we must also and at the same time disabuse ourselves of the attachment to psychosocial race. In the realm of biology it must become crystal clear that there is no race, only genetic heritage. In the psychosocial realm it must become equally clear that there is no race, only racialization.

Racialization (as explained in a previous post and in The Arc of a Bad Idea: Understanding and Transcending Race) is the process and pattern by which we fabricate social identity groups based on superficial markers (phenotypic characteristics such as skin color, facial features, and hair type); sort people into categories based on those skin-deep differences; impute all manner of fictitious qualities (positive and negative) to the constructed categories; treat the false differences as not only real, but essential, hereditary, and immutable; and, finally, act as if the supposed differences between races justify unequal treatment.

Using the distinctions employed by Yudell at al, we must see that just as “ancestry,” and “genetic heritage” are process-based concepts that lead us to explore and examine real and valid relationships between individuals based on genetic similarities and differences, so “racialization” is a process-based concept that elucidates how the pattern-based concept of race is generated and imposed as a valid psychosocial differentiator on individuals who, but for the effects of actions based on racialization, would not be living qualitatively unequal lives.

Of course the authors are right and responsible to assert that the study of racism and its biological effects (as well as its pernicious non-biological effects, I presume) is crucial if we are to address structural and systemic inequities and injustice that play out between socioculturally defined racial groups. We will not, however, be able to undo the pattern of re-invoking, reproducing, reaffirming, re-activating, and re-entrenching the harmful false notion of socioculturally defined racial groups until we shift from participating in and perpetuating racialization to debauching, disrupting and disavowing it. People are not members of races. There are no races. People have been and continue to be racialized with advantageous results for some and disadvantageous results for far too many. The health, economic, educational, justice, and other inequities that result from racialization must and can only be fully, accurately and effectively researched, monitored, and addressed by shifting from the re-incarcerating language of race to the elucidating language of racialization.

Biologists, along with all of us who seek to think more carefully, clearly, and effectively about genetic diversity and social plurality, must be thoroughgoing in the advocacy of making the challenging but necessary move from the racial worldview in which the concept of race dictates false convictions and misguided action, to the nonracial worldview in which we see race as the product of the practice of racialization and act strenuously and relentlessly to put an end to that practice. We must stop thinking of and speaking of individuals with variable genetic heritages, who are certainly usefully classifiable into many many kinds of populations based on the solid basis of genetics, as members of races. Continuing to indulge or succumb to racialization in the realm of social science and social justice only abets the same harmful thinking and associated practices in all other areas of intellectual and civil spheres.

Featured image credit: “Scylla Attacking Odysseus’s Ship (Original)” by Roger Payne, via The Book Palace.

The post Taking race out of human genetics and memetics: We can’t achieve one without achieving the other appeared first on OUPblog.

Why e-cigarettes have an image problem

E-cigarettes have an image problem. I mean this in two different ways. They are still seen as controversial products, often featuring in dramatic stories about battery explosions or toxic substances. Most of these stories play on public fears, exaggerate their claims, and are unhelpful for fostering a constructive public debate. But more generally, e-cigarettes have an image problem in that no one agrees on what they represent: are they a new leisure device providing a safer way to smoke, a pharmaceutical quitting tool, a ploy from Big Tobacco to find new profit streams, or something else entirely?

Of course, on a basic level, we know what they are. E-cigarettes are devices for heating up a nicotine-containing liquid solution to produce a mist or vapour instead of cigarette smoke. From their appearance to their use and operation, they mimic the feel of real cigarettes without producing the more harmful side effects of actually combusting tobacco leaves. Smokers who turned “vapers” have described how important this mimicry really is: the tactile feel of the devices in your hand, the “throat hit” as you draw vapour into your mouth, and the sensation as your body reacts to the nicotine in much the same way as it would if you were smoking. The great appeal and apparent success of e-cigarettes lies in how closely they can fool your body and mind into believing you are smoking. Successive generations of products are coming closer and closer to this ideal (and they are developing very rapidly), or even surpassing it in favour of almost infinite customization, and personalization of the smoking experience.

This mimicry of conventional smoking might suggest that vapers and the e-cigarette industry sympathise with Big Tobacco when it comes to defining e-cigarettes. But their relationship is much more strained and complicated – to simplify things we can talk about two different vaping wings: pragmatists and idealists.

The idealists are the most fervent and politically active members of the vaping community. They think regulators should keep their hands off e-cigarettes for fear that they smother the nascent industry with needless, burdensome rules. In their view, free vaping means fewer rules, lower costs, more vaping, and therefore more lives saved as conventional smokers make the switch. The idealists have no connections to Big Tobacco: the companies are mostly small and medium-sized enterprises that make up the majority of the e-cigarette industry. They want e-cigarettes to be seen as a new product category, not as either a tobacco product or a pharmaceutical product.

In contrast, the pragmatists believe that regulation is necessary for the e-cigarette industry to develop and evolve into a mature and stable product category. Rather than oppose any attempts to associate e-cigarettes with other tobacco or pharmaceutical products, this group simply argues for moderation in these endeavours in order to build up a long-term, compromise solution that is at least acceptable to all parties involved. The idea is that stable expectations about the rules governing the product will encourage investment and longevity. In this group we can find certain e-cigarette companies and associations, but also Big Tobacco (all of which own e-cigarette brands by now) – however, there is much less representation of individual vapers who see little point in campaigning for stable rules.

Image credit: electronic cigarette by InspiredImages. Public Domain via Pixabay.

Image credit: electronic cigarette by InspiredImages. Public Domain via Pixabay.When regulatory authorities were first confronted with this new product, it is fair to say that they did not know much about what e-cigarettes were or did. Most jurisdictions opted for a form of pharmaceutical regulation to level the playing field with nicotine replacement therapies such as the Nicorette range of products. But this was strongly resisted by vapers who did not want to see their current range of products become medicalized, and themselves become stigmatized in the process, as addicts in need of treatment. A good part of vapers have no intention of quitting, but use e-cigarettes as a long-term, potentially healthier alternative to smoking. Pharmaceutical regulation was successfully challenged in court in several jurisdictions, and a search for new regulatory solutions began. This is when the image problem became a regulatory problem, because regulators faced a dilemma.

On the one hand, you have the idealists demanding free vaping and no regulation. They are idealists because regulators view their political solutions as naïve and lacking in credibility. On the other hand, you have the pragmatists, who are savvier in navigating the political landscape but suspect and dubious due to their connection to Big Tobacco. The main objective of tobacco control is tobacco cessation – to urge smokers to quit as soon as possible and to bring about the end of the tobacco industry. If you see the e-cigarette as a new profit stream for the tobacco industry, the only sensible solution is to ban it.

In the European Union’s recent regulation of the Tobacco Products Directive, it required a concerted effort from outsiders working with the fringes of tobacco control to challenge the norm of tobacco cessation with an alternative norm of tobacco harm reduction. This ultimately proved useful in providing a policy solution that had traction with vapers, while balancing the views of experts and the industry. In doing so, it proffered an image of e-cigarettes as harm-reducing tobacco products, which should be regulated alongside other tobacco products, but cautiously embraced for their potential public health benefits. This image has proven its success in one setting, but numerous contending interpretations still abound.

Discussion about the pros and cons of vaping, its health benefits and potential risks, is healthy and warranted. But before we start making sweeping claims about what e-cigarettes do, we need much more discussion about what e-cigarettes are and what we want them to be, and to appreciate that they mean different things to different people. Solving the image problem of e-cigarettes is paramount if we want to realize their potential public health benefits.

Featured image credit: Vaping NJOY Vaporizer Pen by Lindsay Fox. CC-BY-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why e-cigarettes have an image problem appeared first on OUPblog.

Classics in the digital age

One might think of classicists as the most tradition-bound of humanist scholars, but in fact they were the earliest and most enthusiastic adopters of computing and digital technology in the humanities. Today even classicists who do not work on digital projects use digital projects as tools every day.

One reason for this is the large, but defined corpus of classical texts at the field’s core: the earliest digital projects in classics were textual tools. Computers help to process and analyze large amounts of text, particularly when it is incomplete or fragmentary, as is often the case. As early as 1946, Roberto Busa began work on the Index Thomisticus, persuading IBM founder Thomas Watson to sponsor the project, which took 30 years to complete and was originally published in print. In the 70 years since, text-based digital projects like Thesaurus Linguae Graecae, the Bryn Mawr Classical Review, and ancient text collections like Oxford Scholarly Editions Online have become firmly embedded in the practices of classics scholars, and some, like The Perseus Digital Library, have pioneered the linking of text to images.

More recently classicists have started to use digital tools in studying art and material culture. Archaeologists use digital modeling, GIS, and 3D printing in their work. Archaeological reports are now quickly published and made discoverable through open-access digital publishing, while online databases for coins, inscriptions, and other small finds bring information to researchers’ fingertips. Now that advanced imaging techniques are available, researchers are using multi-spectral imaging to digitize textual artifacts such as the Herculaneum papyri, make readable texts that cannot be read by traditional mechanical means.

Ancient historians are also using digital technologies in analyzing and virtually re-creating physical space. Digital mapping helps scholars study physical change and population distributions helps keep track of ancient places. Digitization has also helped other scholars re-create ancient maps, such as the Severan Marble Plan of Rome, an ancient groundplan of every architectural feature in ancient Rome, or even to map the landscape of ancient publications onto a physical map of ancient Pompeii. More recent technological advances have allowed classics scholars to even use virtual reality to experience and experiment with whole ancient environments.

Joining these and many other digital tools available to the student and scholar of the ancient world is the new Oxford Classical Dictionary, which this year has made the transition from a static print-first publication to a dynamic digital resource that is poised to grow and evolve with the field. Editor in chief Sander Goldberg tells us about how the OCD fits into an increasingly digitized scholarly landscape.

Featured image credit: MacBook Pro, by Remko Van Dokkum CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Classics in the digital age appeared first on OUPblog.

March 22, 2016

Passion and compassion: The people who created the words and numbers of environmental science

These are the images I carry in memory that form my understanding of passion and compassion in science: Rachel Carson waking at midnight to return to the sea the microscopic marine organisms she has been studying, when the tidal cycle is favorable to their survival; John Muir clinging to the upper branches of a tall pine during a violent storm, reveling in the power of natural forces. Although I did not observe these events, reading about them created a persistent memory—because I share the passions underlying these actions.

Other events of which I have never read a description but can imagine: Clair Cameron Patterson, painstakingly developing the basis for geological chronologies based on the decay rates of radioactive elements, working largely in the rational environment of a research lab. At some point during his research, Patterson becomes aware of pervasive lead contamination in soil, air, water, and the tissues of living organisms. And then a different kind of passion drives him to act on his knowledge as he undertakes a long struggle to alert others to the deadly effects of leaded gasoline, as he does so enduring personal vilification in the often irrational world of human society.

Another imagined vignette: Robert MacArthur and E. O. Wilson developing the mathematical equations underlying the concept of island biogeography during lively discussions over a pad of paper or a chalkboard. Usually only mathematicians find beauty in equations, but the implications of those equations can create beauty for all of us. The equations of island biogeography gave rise to the realization that the number of species able to persist in a protected area depends partly on the size of that protected area, thus providing an important planning tool for conserving ecosystems. Wilson, in particular, has lived long enough after developing these equations to argue passionately for the importance of protecting ecosystems and organisms.

Rachel Carson, author of Silent Spring. Official photo as FWS employee. c. 1940 from the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Rachel Carson, author of Silent Spring. Official photo as FWS employee. c. 1940 from the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Passion and compassion underlie environmental science. Passion, because no one carefully records the annual arrival of the swallows, as Gilbert White did in 18th century England, or spends 738 days living in a redwood tree slated to be logged, as Julia Hill did in the 20th century United States. What could be more worthy of time and energy than understanding and protecting the natural world? Compassion, because although those who strive to understand and protect non-human lives ultimately benefit humanity, they can see past the human-centered world view that blinds so many of us to other organisms’ inherent right to exist. Rachel Carson could simply have discarded the water containing those microscopic creatures. No one would have known and marine ecosystems would have continued unchanged. But because Carson possessed passion and compassion, she protected those, at least to us, most obscure of lives, and she wrote the best-selling books The Edge of the Sea, Under the Sea-Wind, The Sea Around Us, and Silent Spring, which changed how we view and interact with the world.

The people behind the words and numbers of environmental science care deeply about something beyond themselves and beyond the immediate needs of other people. The key figures of environmental science engage intellectually with seemingly abstract concepts that, over long time spans and large spatial extents, create concrete results. Half a century ago, few people gave any thought to the chemical composition of Earth’s atmosphere. Now, thanks to the measurements and numerical models of carbon dioxide levels in the air at Mauna Loa, Hawaii and ozone levels over the poles, even the most scientifically ignorant politicians argue vehemently about atmospheric chemistry and warming climate. Individual scientists such as Paul Crutzen and James Hansen created the measurements and numerical models and, most importantly, raised awareness of the phenomena represented by the measurements and models.

Similarly, despite Rachel Carson’s pioneering writings about pesticides, half a century ago, only dystopian fiction writers might have imagined a future in which freshwater fish exhibited both male and female physiological traits, girls as young as two started growing breast buds, and rates of cancer shot up to 40% of the population in high-income countries. Now, the research and writing of scientists such as Theo Colborn, John Cairns, and Sandra Steingraber have made people increasingly aware of the ubiquity and dangers of endocrine-disrupting synthetic chemicals in our food and water.

A pair of quotes encompasses the passion and compassion of environmental science. First are William Blake’s lines, “To see a world in a grain of sand and…hold eternity in the palm of your hand.” Most scholars focus on a narrow portion of the enormous spectrum of intellectual enquiry, spending a life understanding how rivers process nutrients from the surrounding uplands or how elephants communicate with one another and structure their family groups. But this narrowly focused, deep research is the telescope or microscope through which we perceive worlds otherwise invisible to people. The research allows us to become more fully aware of the rich, complex planet on which we live.

The second quote is Aldo Leopold’s famous lament, “One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds.” The insight of deep research leads to awareness of how the cumulative activities of billions of people are altering our rich, complex planet, tearing ragged holes in the fabric of ecosystems as we drive increasing numbers of species to extinction, clear native vegetation and reconfigure surface topography across vast swaths of Earth’s surface, and dam the flow of rivers. Awareness, coupled with passion and compassion, drives those who seek to educate others and to act on behalf of the natural world, whether that action takes the form of a book, testimony at a governmental hearing, or protest at a threatened site.

Who would choose to live alone in a world of wounds if they could act to heal those wounds?

Featured image credit: BlueMarble-2001-2002. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Passion and compassion: The people who created the words and numbers of environmental science appeared first on OUPblog.

Local opera houses through the ages

Nineteenth and twentieth Century opera houses are finding new lives today. Opera houses were once the center of art, culture, and entertainment for rural American towns–when there was much less competition for our collective attention. Though they faded out of fashion over the years, opera houses have recently been experiencing a resurgence. Author Ann Satterthwaite, of Local Glories: Opera Houses on Main Street, Where Art and Community Meet, reveals the metamorphic stories behind numerous United States opera houses dating back to the nineteenth century with this slideshow of historical and contemporary photos.

Stonington, Maine’s Opera House

Stonington, Maine’s opera house beckons to all entering the harbor. This early twentieth century building still houses the opera house, which has been restored and brought up to date for contemporary theater and entertainment. © Image courtesy of the Deer Isle-Stonington Historical Society.

Thorpe Opera House

Most opera houses in small towns like David City, Nebraska were proud buildings on Main Street. The opera house would be on the upper floors and commercial establishments on the ground floor. © Image courtesy of the Thorpe Opera House Foundation.

Pueblo, Colorado 1890

Some were grand buildings like Pueblo, Colorado’s 1890 opera house, designed by the famous Chicago architects Sullivan and Adler. © Image courtesy of History Colorado.

Burlington, Vermont’s Howard Opera House

Many interiors were grand like Burlington, Vermont’s Howard Opera House. © Image courtesy of Special Collections, University of Vermont Bailey/Howe Library.

Mineral Point, Wisconsin

Some opera houses were and are in town halls, others in buildings with the local library. Shown here in Mineral Point, Wisconsin, the city hall, library, and opera house are all together in one building. © Image courtesy of the author.

Mark Twian

Famous actors and actresses like Sarah Bernhardt, lecturers like Mark Twain, and many theater troupes, opera companies, sundry magicians, and entertainers performed in opera houses across the country. They made the late 19th century a time when more places were exposed to live entertainment than at any period before or since. © Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

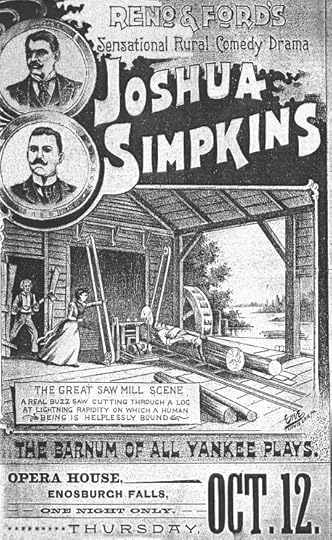

Joshua Simpkins

Much of opera house entertainment was provided by regional traveling companies like Reno and Ford, which presented Joshua Simpkins, a “sensational rural comedy drama,” in the opera house in remote Enosburgh Falls, Vermont. © Image courtesy of the Enosburg Historical Society.

Fremont Opera Group

Local groups also offered performances. Here Fremont Nebraska’s Oriole Opera Company is presenting the popular Chimes of Normandy in 1888 at the Love Opera House in Fremont. The town also enjoyed performances by the local Fremont Dramatic Company. © Image courtesy of the Louis May Museum.

Trenton Political Convention

The opera house was a busy hall where far more than cultural events took place. As a large hall and neutral turf, school recitations and graduations, sports events, elections, political speakers and even political conventions took place in opera houses. Here New Jersey’s 1877 Democratic State Convention convened in Trenton, New Jersey’s Old Taylor Opera House. © Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Tibbits Old Opera House

By the early twentieth century, movies in large, sumptuous theaters were making the opera house on main street seem an obsolete institution. Many opera houses were torn down, others sputtered along, and many were dormant for over fifty years. Here, the Tibbits Opera House stands in disrepair in Coldwater, Michigan. © Image courtesy of the author.

Tibbits New Opera House

However, by the 1970s the local opera house was beginning to be recognized as an important cultural and community asset. Towns everywhere were bringing the old opera house back to life. In Coldwater, Michigan, the Tibbits Opera House escaped the wrecking ball in the 1960s, and has been restored; first shedding its protective façade and then restoring its cupola and finally its façade. Image courtesy of Tibbits Opera House. © Photograph by Sarah Zimmer, 2013.

Goodspeed Today

The Goodspeed Opera House perched on the bank of the Connecticut Five in East Haddam, Connecticut is now a stellar example of a revived opera house as well as one that has concentrated on musical theater. © Image courtesy of the author.

Stonington Opera House

Many revived opera houses have year-round theater, concerts, dances as well as community programs. Here is a production of Shakespeare’s Cymbeline at the Stonington, Maine Opera House in 2013. © Image courtesy of the Stonington Opera House and Opera House Arts.

Hubbard Hall

Even opera companies have been formed in small towns like Cambridge, New York with a population of only 2,000. In 2015 Cambridge’s Hubbard Hall Opera Theater performed Verdi’s Rigoletto. © Image courtesy of the Hubbard Hall Opera Theater.

Claremont Opera House

Opera houses today are alive with not only cultural programs, but with many community activities including political events, as they were in their nineteenth century heyday. Here in the Claremont, New Hampshire Opera House Bernie Sanders attracted a full house on February 2, 2016. © Image courtesy of Bill Binder.

Trenton Political Convention

The opera house was a busy hall where far more than cultural events took place. As a large hall and neutral turf, school recitations and graduations, sports events, elections, political speakers and even political conventions took place in opera houses. Here New Jersey’s 1877 Democratic State Convention convened in Trenton, New Jersey’s Old Taylor Opera House. © Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Image credit: “Pinos Altos Opera House” by Tom Blackwell, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Local opera houses through the ages appeared first on OUPblog.

The evolution of flute sound and style

This March, we’ve been focusing on the flute and its history and importance in the music scene. Resident OUP history editor Nancy Toff is also active in the flute world as a performer, researcher and instructor. In order to delve into Nancy’s wealth of knowledge about the flute, we asked Meera Gudipati, currently attending the Yale School of Music as a Master of Music, to interview her about flute performance, music history, and other favorite flutists.

Performance practice has increasingly become more important in the music world today. How has the flute sound and style changed over the last decades?

Since the advent of LP recordings in the mid-20th century, classical flute sound has become more internationalized. National styles are far less distinct than they once were. But at the same time, there has been a return both to historically informed performance of early music (on both historical and modern instruments), and fascinating experimentation with new sounds and new instruments—for example, Robert Dick’s glissando headjoint and his many bags of sonic tricks, and Clare Chase’s electronically enhanced performances with the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE).

What are some of the flute repertoire pieces you discovered that deserve more attention?

Nancy Toff at a signing at the National Flute Association’s 40th Annual Convention. Photo courtesy of Nancy Toff.

Nancy Toff at a signing at the National Flute Association’s 40th Annual Convention. Photo courtesy of Nancy Toff.I’ve always thought that the Ibert Pièce for solo flute was an undiscovered gem, and there’s a lot of French woodwind ensemble repertoire from the first quarter of the twentieth century that’s in unjustified semi-retirement. I’m researching the career of Louis Fleury right now, and finding lots of repertoire to revive.

What are some of your favorite recordings of flutists?

It’s hard to play favorites, but… William Kincaid’s version of the Griffes Poem is stuck in my ear as the way to play it; he learned the piece from Barrère, for whom Griffes wrote it. It has the most color of any recording available. Julius Baker’s disc of the Debussy Sonata for flute, viola and harp is another classic, and the LP of baroque cantatas with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Jean-Pierre Rampal is an examplar of stylish playing. Of today’s generation, I won’t play favorites!

What is your favorite part about being an archivist for the New York Flute Club and National Flute Association?

Two very different things. For the NY Flute Club, the detective work of finding historical programs that our archives are lacking. I’ve turned up odd programs in Woodstock, NY; Atlanta; Chapel Hill, NC; and other seemingly unlikely archives. For NFA, getting to talk with the leaders of our profession, and recording oral histories with some of the leading players and composers of the twentieth century.

Do you have any new projects that you are working on?

I’ve been researching the life and work of Louis Fleury for several years now. Unfortunately, I haven’t had the time to do the European research that I need and want to do. And I’m also looking forward to the centennial of the New York Flute Club in 2020, which will be the focus of some wonderful celebrations.

You have created your career around your passion for the flute and history. What do you love most about your daily life?

Yale School of Music student Meera Gudipati with her flute. Photo courtesy of Meera Gudipati.

Yale School of Music student Meera Gudipati with her flute. Photo courtesy of Meera Gudipati.I get to satisfy my intellectual and musical curiosity every day. My authors educate and challenge me in all sorts of interesting ways, and I learn both from them and from my musical research. I love working on projects with my performing colleagues and seeing the fruits of my research show up on concert programs and in music curricula. I get a huge kick out of being able to help answer research questions for a wide variety of scholars.

During your studies with Arthur Lora and James Pappoutsakis, what are some of the most important lessons you learned?

They were very different teachers. Arthur Lora taught me in a very well-rounded way, technique, sound, the basics of ornamentation, a wide range of literature. He recognized my interest in history early on and built parts of lessons around that. By contrast, Mr. Pappoutsakis was all about sound, and he taught totally by demonstration—he did so much to improve the quality of my tone. And of course he worked a great deal on orchestral excerpts, which was extremely valuable.

What are some of the best libraries or centers for doing research about the flute?

The single most important archive in the United States is the Dayton C. Miller Flute collection in the Library of Congress, which has 1,500 instruments, thousands of pieces of music, thousands of books, trade catalogs, works of art, correspondence. It’s a flute historian’s paradise. And of course the main collections of LC have many treasures as well, both published music and literature and archival collections of musicians (Copland, Bernstein, etc.). The Marcel Moyse papers and the Joachim Andersen papers are at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, as are the papers of many other musicians important to flute history. For the Paris Conservatoire, the incubator of modern flute playing, the archives are at the Archives Nationales in France, but there is also a rich lode of materials at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. All the great libraries of Europe have wonderful collections of music, and happily, it’s possible to do a great deal of advance, preparatory work with their online catalogs to make research visits more efficient.

Featured image: “288/365 ~ Band Performance” by Ray Bouknight. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The evolution of flute sound and style appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers