Oxford University Press's Blog, page 528

April 1, 2016

Announcing the winners of this year’s Grove Music Spoof Article Contest

In honor of April Fools’ Day, we are pleased to announce the winners of the 2016 Grove Music Spoof Article Contest.

This year’s expert judges included:

Deane Root, Editor in Chief of Grove Music Online, and Professor of Music, Director and Fletcher Hodges, Jr. Curator of the Center for American Music, University of Pittsburgh, has been immersed in Grove style since he worked under Stanley Sadie on the first New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians.

Daniel Goldmark is Professor of Music at Case Western Reserve where he serves as Head of Popular Music and the Director of the Center for Popular Music Studies. He was an Area Editor for the second edition of The Grove Dictionary of American Music, is editing the forthcoming Grove Guide to American Film Music, and has written extensively on comedy and music in American film, including his 2011 book Funny Pictures: Animation and Comedy in Studio-Era Hollywood (U. California Press).

Anna-Lise Santella is Senior Editor for Music Reference at OUP, a position that includes serving as publishing editor of Grove Music Online. She spends a lot of time with style guides and once read the 1927 edition of Grove cover-to-cover. For fun.

We received an impressive crop of submissions this year. Some highlights:

35 spoof articles were submitted by 29 authors for an average of 1.2 articles per author (3 submissions per person were permitted).

17 submissions came from the United States.

9 submissions came from the United Kingdom.

1 submission each came from Malta, Portugal, and Switzerland.

22 submissions were biographies.

Careers of biographees included 14 composers, 4 singers, 1 pianist, 1 euphonium player, 1 instrument inventor, and 1 music hall artist with a particular talent for the tambourine.

5 articles described musical instruments.

Several articles offered pointed satire inspired by the likes of Donald Trump, the Grammys, and even Grove.

One article, on “Leonard Berenstain” submitted by Andrew Miller, brazenly copied nearly word for word (with appropriate name changes as warranted) the opening of Grove’s article on Leonard Bernstein, although its final bibliography item is found nowhere in either Grove or in the annals of publishing:

Berenstain and J. Berenstain: The Berenstain Bears and the Trouble with Music (New York, 1962)

The fake books that contestants invented for their bibliographies would fill a very entertaining shelf in the Grove offices. Our favorite overall bibliography was one submitted by last year’s contest winner Joanna Wyld with her article “Mildew, Tilly,” who graced the stages of nineteenth-century English music halls with her show “Tilly the Tremendous Tambourine Tickler.”

T. Mildew: Aint’ Life Jolly, Ain’t Life Sweet, Until You Punch Sigmund Freud in the Face—an Autobiography (London, 1925)

P.S. Pettilove: Le Pétomane: Life’s a Gas! (Oxford, 1980)

J.J. Gordon submitted an article on a 1970s craze for opera spin-off sitcoms that seems like a missed opportunity in television history. The Grove editorial staff hopes that J.J. will be soon be in Hollywood pitching Kurvy’s Kafé, in which “Kurwenal leaves Tristan, Isolde, and Cornwall behind to open up a cheap-eats diner on a dead highway in the American southwest.”

In short, the judges had their work cut out for them. However three articles quickly rose to the top.

This year’s winner is Caroline Potter for her article “Musical cheesegrater.”

Judge Goldmark observed, “The author impressively inserts this instrument into the wide chasm of instrumental possibilities first opened by the Futurists and the Dadaists, forcing us to question whether it’s possible an instrument like this didn’t actually exist, which I’d say is the goal of obfuscatory historiography. The author could have constructively raised the entire question of how the choice of cheese becomes a performance practice issue, which leads to training cheesemongers as moonlighting musicians. Also: please add me to the Gastromusicology email list forthwith!”

Judge Root added, “The translations are a nice touch, as are institutional references. (It does, however, omit the option of playing the instrument from the inside, which has occurred during Purimspiels.)”

* * * * *

Musical Cheesegrater

(Fr. râpe à fromage musicale; It. grattugia musicale)

A percussion instrument that enjoyed a brief vogue in Rome and Paris in the 1910s and early 1920s. In the Hornbostel-Sachs classification the instrument is reckoned as a friction idiophone. Of metal construction, it typically has four sides, each with raised perforations of a particular size. The player strokes one or more of the sides with a metal implement, producing a distinctive rasping sound. A rare rotating variant, where a perforated barrel is turned using a crankhandle to create friction against metal tangents, survives in the Musée de la Musique in Paris. The musical cheesegrater is cited in a posthumously published appendix to Luigi Russolo’s celebrated manifesto L’Arte dei rumori in the fourth category of his sound classification (screeches, creaks, rumbles, buzzes, crackles, scrapes). Its best-known use is in Maurice Ravel’s opera L’enfant et les sortilèges (1924), where it is rubbed with a triangle beater.

The musical cheesegrater was employed by Italian Futurist composers and associates of the Dada movement in Paris, and its popularity and decline mirrors the fortunes of these artistic groupings. The manuscript of Erik Satie’s Rabelais-themed Trois petites pièces montées (1919) features the instrument rubbed with a hard cheese, though scholars disagree whether Satie intended this to be a percussion instrument or part of a projected staging. Edgard Varèse showed enthusiasm for the musical cheesegrater during a dinner with Russolo; it appears in sketches for Amériques (1918-21), but not in the final version. Recent academic research in gastromusicology has revived interest in the instrument.

Bibliography

Russolo, Luigi, L’Arte dei rumori: manifesto futurista (1913; appendix published posthumously in English translation, London, 2013)

Orledge, Robert, ‘Chronological catalogue of the works of Erik Satie’ (London, 2010, 307)

Carolina Comté

* * * * *

Congratulations to Caroline, who wins $100 in OUP books and a year’s subscription to Grove Music Online.

The runner-up is Eric Saylor for his article “Raymond, Delray Odabee.” Judge Root called this article “rich in knowledgeable namedropping within the history of shapenote hymnody (including the author’s name), though embellished more storytelling than in most Grove entries.”

Judge Goldmark said, “I assume the author of this entry is either an Alabama native or at least quite handy with an atlas, given the liberal and very skillful use of the characteristically colorful names where the composer was born and died, as well as the mention of Winston County and its infamous opposition to secession, an island of progressive thoughts in a sea of secessionists. This brief story of a shape-note wunderkind really stood out as being entirely plausible without being ridiculous, from the names of the fuging tunes, or the Alabamians’ heated reaction to them.”

* * * * *

Raymond, Delray Odabee

(b nr Booger Tree, Alabama, 7 Apr 1814; d Double Springs, Alabama, 30 May 1871). American composer, teacher, and politician. Heir to a vast sorghum fortune, Raymond’s earliest musical experience involved singing shape-note hymns at Walker’s Chapel Church, being able to lead classes from the square “with great tenacity” as a six-year-old.

Upon moving to Double Springs in 1838, Raymond quickly became a popular teacher of composition and singing. Court documents from a copyright infringement suit imply that he taught the rudiments of music to John McCurry, compiler of The Social Harp (1855), though this claim has never been verified. Although best known for his fuging tunes “Rectitude” and “Hancock” (both 1839) and the buoyant revivalist hymn “Fritters” (1841), Raymond also wrote several classically-inspired stage works, most notably Euterpe in Tuscaloosa, or, The Muse in the News (1844), a farce in two acts.

In 1848, Raymond was elected to the Double Springs town council as a Whig, changing his party affiliation to Republican in 1856. An outspoken opponent of secession, he successfully led a campaign to ally Winston County (Alabama) with the Union in 1861. After the war, hoping to capitalize on local enthusiasm for the Confederate defeat, he released The Grand Harp of the Republic (1866), a shape-note compendium featuring such new tunes as “Lincoln,” “Appomattox,” “Union Forever,” and the fiery “Sherman’s March.” His misreading of the market led to the burning of the entire inventory of hymnbooks by an angry mob, and to Raymond’s subsequent bankruptcy in 1868; the few surviving copies of The Grand Harp are much prized by collectors. He died three years later of complications.

Bibliography

Blessing, Hymnody in the American South, 1776–1895 (Philadelphia, 1909)

Rassity, Yankee Doodle Dixie: The Free State of Winston (New York, 1998)

Sophronia Denson

* * * * *

Finally, one article ruled ineligible for competition, but its evocation of Grove style was so pitch-perfect that we award it a special honorable mention. Daniel R. Melamed’s article on the seldom-discussed neume “Sphinculus” wowed the judges.

Judge Root called the article, “Body humor clothed in Latin and impeccable scholarly writing style, brilliantly composed. It’s the most thoroughly integrated spoof of the submissions and the closest thing to the spoofs composed by the 1970s Grove editorial staff (two of which made it into the first printing of The New Grove). It’s the best I’ve seen in 35 years.”

Judge Goldmark felt similarly. “Definitely made me laugh out loud; I found this quite funny and clever. The slightly altered chant title ‘Ex laxis quaeunt’ was excellent. I could have added that it seems like this note might be related in some way to the fabled turba brunus referred to in the episode of South Park titled ‘World Wide Recorder Concert,’ for which this note might be an important precursor.”

* * * * *

Sphinculus [cursive sphinculus]

(? from Lat. sphinxis: ‘enigma’).

Neume appearing in Western chant manuscripts of the early late Middle Ages, typically at the tail end (cauda) of a chant. It indicates a three-note figure in which the lower of the first two tones is sounded as the upper neighbour of the third.

Its further meaning is obscure but it is thought to signal a tightening of all aspects of performance. There have been heated arguments about its rhythmic interpretation, with many older scholars arguing for regularity; research does not yet have complete control over the sphinculus.

It is curiously unmentioned by Huglo (‘Les noms des neumes et leur origine’, EG, i, 1954, pp.53–67).

The neume finds its classic expression in the hymns “Ex laxis quaeunt” and “Aperientes me” sung as petitions for relief to St Magnesia, usually in the Night Hours; and at the end of certain tracts. In secular music it is closely associated with the title character of the Roman de Fauvel.

Graphical forms vary; the sphincula of German scribes tend to be tight, whereas those of the French are typically much looser. (For illustration see NOTATION, Table.) It almost always closely follows another neume, the descending colon, for which it serves as a kind of stop. Its earliest appearance is in the Kaufbeuren MS (D-Klo WC 00) but it is also frequently encountered in Scots paper rolls.

Bibliography

Wogelweide, Wanda : The manuscript Kaufbeuren WC 00 (diss., U of Waterloo, 1990)

Wogelweide, Wanda : ‘The cursive sphinculus in the manuscript Kaufbeuren WC 00’, PMM, i (1992), 167–73

Wanda Wogelweide

* * * * *

Thanks so much to all the contestants and a special congratulations to our winner. We hope to see you all again next year!

Headline image credit: Sara Levine for Oxford University Press.

The post Announcing the winners of this year’s Grove Music Spoof Article Contest appeared first on OUPblog.

10 surprising facts about Ancient Egyptian art and architecture

Ancient Egyptian art dates all the way back to 3000BC and provides us with an understanding of ancient Egyptian socioeconomic structures and belief systems. The Ancient Egyptians also developed an array of diverse architectural structures and monuments, from temples to the pyramids that are still a major tourist attraction today. But how much do you know about Ancient Egyptian art and architecture? Christina Riggs, author of Ancient Egyptian Art and Architecture: A Very Short Introduction, tells us ten things we need to know about Ancient Egyptian art and architecture:

A common preconception is that Ancient Egyptain art all looks the same. In reality, it is very diverse and the style and symbolism of the art depends on the region.

When Egyptian art does look the same, it is for a very good reason; it is often based on religious beliefs.

A lot of the artists or architects from Ancient Egypt are unknown and remain anonymous.

Some forms of art were created purely for sacred or magical purposes.

Much of Ancient Egyptian art was not meant to be seen by ‘normal people’. The art was created in secret to be viewed by the elite and it was “too powerful to be viewed by the general public.”

A lot of the buildings you can see and visit in Egypt, such as temples, pyramids, and tombs, would have only been seen at the time by very few people.

We think of Mummies as an Ancient Egyptian burial ritual but they were actually very sacred objects. Only very few people were ever mummified in Ancient Egyptian history and only the Priests were allowed to see them.

It was only modern studies on race and racial differences that made Mummies become “medical objects.”

Ancient Egypt isn’t necessarily more interesting than other ancient empires. Perhaps it is seen as more exotic by Europeans because it is so different to our modern culture, whereas we still see similarities between our culture and Ancient Greece for example.

You will see Ancient Egyptian art and architecture everywhere, and not just in Egypt. Ancient Egyptian art and architecture continues to inspire and influence modern designers all around the world.

Featured image credit: “Hieroglyphics”, by niki_vogt. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post 10 surprising facts about Ancient Egyptian art and architecture appeared first on OUPblog.

March 31, 2016

A reimagined Wonderland, Middle-earth, and material world

Lewis Carroll, J.R.R. Tolkein, and Philip Pullman are three of the many great writers to come out of Oxford, whose stories are continually reimagined and enjoyed through the use of media and digital technologies. The most obvious examples for Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland are the many adaptations in theatre, film, and television. Tolkein’s The Lords of the Rings, with all of the facets of Middle-earth, has developed incredibly in the film and gaming industries. Pullman’s His Dark Materials has also seen success in film, particularly in the The Golden Compass, an adaptation based on the first novel in the trilogy.

In a discussion held at the Oxford Museum of National History, Robert Douglas-Fairhurst (Professor of English Literature, University of Oxford), Stuart Lee (Member of the English Faculty and Merton College, University of Oxford), and Margaret Kean (Helen Gardner Fellow in English, St Hilda’s College, University of Oxford) explore the use of media and its effects on these authors’ works. Together they raise questions and encourage conversation about how the use of digital tools gives stories new and diverse afterlives.

Featured Image: “Illustration from The Nursery “Alice”, containing twenty coloured enlargements from Tenniel’s illustrations to “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,” with text adapted to nursery readers” by John Tenniel. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post A reimagined Wonderland, Middle-earth, and material world appeared first on OUPblog.

And the lot fell on… sortition in Ancient Greek democratic theory & practice

Some four decades ago the late Sir Moses Finley, then Professor of Ancient History at Cambridge University, published a powerful series of lectures entitled Democracy Ancient and Modern (1973, republished in an augmented second edition, 1985). He himself had personally suffered the atrocious deficit of democracy that afflicted his native United States in the 1950s, forcing him into permanent exile, but my chief reason for citing his book here, apart from out of continuing intellectual respect, is that its title could equally well have been ‘Democracy Ancient’ Versus ‘Modern.’ For in the matter of the dēmokratia (‘People-Power’) that the Greeks invented (the word as well as the thing) ancient Greece was a desperately foreign country – they did democracy very differently.

It is quite easy to compile a checklist, perhaps even a decalogue, of differences between their democracy (or rather democracies, as there was no one identikit ancient model) and ours (ditto). And in no respect did they and we differ more than on the issue of sortition, that is, the application of the lottery to the conduct of politics (another Greek invention, both the word and the thing, with – again – the accent to be placed on difference as well as similarity between theirs and ours). We today take the exercise of voting in either general or local elections to be the very quintessence of what it is to do ‘democracy.’ The ancient Greeks took the exact opposite view: elections were elitist and for the nobs, appropriate more for oligarchy (the rule of the few rich) than for democracy (the rule of the masses, most of whom were poor), whereas sortition, the lot, was the peculiarly democratic way of selecting most office-holders and all juror-judges to serve in the People’s jury-courts.

The very first extant example of developed Western political theory is to be found in Herodotus’ pioneering fifth-century BCE History of the Graeco-Persian Wars (Book 3, chapters 80-82). It’s a three-way debate staged between advocates of respectively Rule by All, Rule by Some, and Rule by One. The pro-democracy/Rule by All speaker negatively rubbishes the cases that he anticipates will be made by his rivals. Positively, he claims that the system of rule he is advocating has three features that together both distinguish it uniquely from its rivals and demonstrate its pre-eminent choice-worthiness:

1. All office-holders are selected by lot. 2. All office-holders so selected are subject(ed) to public scrutiny and audit. 3. All public political decisions affecting the common weal are taken by all the People altogether. The order is telling – first, sortition; second, accountability; third, popular majority-vote decision-taking.

Image credit: Pnyx hill in Athens by Qwqchris. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Pnyx hill in Athens by Qwqchris. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.So what did sortition have in its favour, according to ancient democratic ideologues, that elections did not? It’s an irony (another good Greek word) of our surviving evidence that we don’t have an awful lot of explicit ancient Greek democratic theory to go on, but here the work of modern political theorists and indeed advocates of applying sortition to enhance our contemporary democratic processes can help us out, for instance Peter Stone’s The Luck of the Draw: The Role of Lotteries in Decision Making (2011). The following eight features have attracted most attention and comment, not all of it positive of course. 1. Descriptive representation – of the population from which the office-holders are to be randomly selected. 2. Prevention of corruption and/or domination (see also 4). 3. Mitigation of intra-elite competition. 4. Control of political outliers – preventing those with nonstandard views from unduly dominating. 5. Distributive justice. 6. Participation. 7. Rotation. 8. Social-psychological benefits – the sense of equality and fairness being made political flesh.

Those eight qualities add up to a powerful contemporary case that I for one find highly persuasive. Were an ancient Greek democrat to be reading through them, however, he (males only need apply in antiquity – legitimate adult citizen males) would surely have found the last four, numbers 5-8, the most relevant by far. The watchwords of ancient Greek democracy were freedom and equality. The use of sortition provided the greatest freedom of action to encourage all qualified citizens to volunteer for important public political positions knowing that the process of selection was random, that it presupposed equality of both opportunity and outcome, that it fostered participation and, perhaps above all, that it recognized and engendered in all citizens in principle a sense of their equal worth, what the Greeks called timē or ‘honour’.

However, as Moses Finley would have been the first to add, there were exceptions; there are always exceptions. The original ancient Greek dēmokratia was Athens, which also developed the most all-embracing forms of that regime. But even the Athenians did not apply sortition to cover absolutely all kinds and conditions of office-holding. For severely pragmatic reasons, the top military and financial offices were allowed to remain elective and not become sortitive; commanding armies and navies or administering public finance were considered far too important public political functions to be left to the random chance of selecting potentially incompetent or corruptible amateurs.

So, how did radical democratic Athenian ideologues reconcile that hard pragmatic fact with their ideology? By invoking and applying rigorously the second distinctive quality promoted by Herodotus’ pro-democracy speaker: that is to say, elected office-holders were subject(ed), regularly and vigorously, to public scrutiny and audit; and should an official’s conduct land him in court, the judgment of his peers would be applied by large numbers of juror-judges serving in the People’s jury-courts – to which they had been allocated by lot. Even the great Pericles felt the hot judgmental breath of democratic Athenian equalitarianism. I can think of quite a few of our (elected) democratic leaders today to whom that breath might likewise be salutarily applied today.

The post And the lot fell on… sortition in Ancient Greek democratic theory & practice appeared first on OUPblog.

Defining biodiversity genomics

Astronomy, mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology. The sciences have unfolded over time as we noticed what was around us, built concepts to describe and tools to observe and measure, and gained a better grasp of the realities of the Universe.

Many say now is the century of biology, the study of life. Genomics is therefore “front-and-centre”, as DNA, is the software of life.

From staring at stars, we are now staring at DNA. We can’t use our eyes, like we do in star gazing, but just as telescopes show us the far reaches of the Universe, DNA sequencing machines are reading out our genomes at an astonishing pace.

Since the start of the era of genomics in 1995, marked by the sequencing of the first complete genome of a free-living bacterium, genomics has spawned numerous subfields. These include ecological, evolutionary, comparative, and environmental genomics, to name a few.

Now it is time for a merger between the millennia old study of the diversity of life, or biodiversity, and genomics – to create “biodiversity genomics”.

DNA is the blueprint of an organism. It not only uniquely identifies as individual, but places it within context in the ‘Tree of Life’, from nearest kin, to population group, up through species and the chain of evolution that links all life through a common, first ancestor.

DNA research is percolating into traditional studies of biodiversity where it is primarily being used to classify and identify organisms and track the movement and histories of individuals, kinship grows, populations, species, and communities (especially when they are microscopic and DNA offers the only way to easily characterize their masses and complexities).

Our need to understand the natural world has never been so pressing.

Likewise, the leaders of the vast genome factories are realizing the importance of looking at genomes in an organismal context, right up to how gene interaction in complex communities.

The first camera was laborious and took minutes to get one, costly photograph. Today we all carry smart phones and snap pictures of anything that catches our fancy.

The same evolution is happening in genomics, and the technology is starting to be fast enough and the cost low enough to start thinking about tackling biodiversity – because it is large.

Gathering samples in biodiversity studies that are suitable for DNA analysis is still a key bottleneck in the growth of this field – but things are changing. Eco-genomic sensors are being developed that can take real-time samples, for example, in the ocean, and genomics experts are travelling to remote parts of the global with DNA sequencers in their backpacks to study the emergence of deadly viruses in real-time.

The de facto sequencing of the Planetary Genome has long been in progress. We are sequencing the Earth, from millions of human genomes down to microbes. There are more than fifty megasequencing projects with hundreds to millions of genomes in the pipeline.

In 2014, the Smithsonian launched a visionary project to catalyze the process and safe-keep suitable samples for the future. The ambitious Global Genomes Initiative (GGI) is working to save biological samples to support the sequencing of at least one representative of the entire tree.

So what is biodiversity genomics? What could this field be once biodiversity and genomics truly marry up?

The phrase “biodiversity genomics” is young, but two key players have self-identified themselves to help catalyze the field.

The University of Guelph’s Center for Biodiversity Genomics (CBG) resides within the Biodiversity Institute of Ontario, and is the culmination of efforts by Paul Hebert to pioneer the global DNA barcoding movement. The mission of the CBG is to “advance species discovery and identification through the analysis of short, standardized gene regions known as DNA barcodes”.

The Smithsonian has wrapped the GGI and related initiatives into an Institute for Biodiversity Genomics, which will “focus its research on characterizing and interpreting these genomes in order to gain a greater understanding of the natural world and the complex interconnectedness of its species and ecosystems”.

“Biodiversity genomics” is also being championed by the Genomic Standards Consortium, who have brought together over thirty groups working in diverse areas of biodiversity, informatics, taxonomy, and genomics to help integrate concepts, people, and data.

All of these activities, and thousands more, herald the dawn of a new extension of the way genomics is applied to real-world questions (and problems) and the acceptance of an immensely powerful new tool within the venerable field of biodiversity.

A key pinch point in this process is the integration of biodiversity and molecular (DNA) databases – a significant challenge but critical goal. Ideally, efforts to unify and raise the profile of the biodiversity informatics community will eventually link together with the rich and growing field of bioinformatics.

So, the definition of the term “biodiversity genomics” must be broad enough to cast a wide net. It must include a wide range of activities and groups and scientific questions.

The term is obviously still aspirational so it is clear that the definition should reflect the possibilities of the future.

It is crucial today to point out where we should head.

Thus, biodiversity genomics can be defined as the use of DNA, as part of a larger framework of integrated data, to answer questions about the diversity and processes that govern the patterns of life on the planet, and how they change.

Our need to understand the natural world has never been so pressing.

The great Harvard naturalist, Edward O. Wilson, has encapsulated the challenges ahead in his new book Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. He suggests we put aside half of the earth for biodiversity for humanity to have a chance. We are actively reshaping the Planetary Genome to meet human requirements, although this is short-sighted and potentially disastrous. Species extinctions are pushing us into a sixth mass extinction at the same time that synthetic genomics and gene-editing is taking off. We are pruning the Tree of Life while we are gaining the profound ability to add to it.

Featured image credit: Night stars, by Pexels. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Defining biodiversity genomics appeared first on OUPblog.

March 30, 2016

Etymology gleanings for March 2016

Preparation for the Spelling Congress is underway. The more people will send in their proposals, the better. On the other hand (or so it seems to me), the fewer people participate in this event and the less it costs in terms of labor/labour and money, the more successful it will turn out to be. The fate of English spelling has been discussed in passionate terms since at least the 1840s. As early as 1848 Alexander J. Ellis wrote that spelling English is the most difficult of human attainments, that English spelling is the most foul, strange, and unnatural there is (his emphasis), and many other equally soothing things. Ellis’s scholarship arouses nothing but admiration, but one may agree with the verdict of The Westminster Review that “if on the subject phonetics he be a little mad, verily much learning hath made him so.”

I am addressing those who, at least provisionally, agree that English spelling should be reformed. The chances that such people will reach consensus are slim, as the fierce storms/tempests in the reformers’ teacup show. The fights were severe in the 1840s, in the 1880s, in the 1910s, and much later. Several hundred and sometimes several thousand people follow this blog. Could I appeal to them to express their opinion on the following propositions that are mine and only mine?

The reform should be instituted in several steps and be as painless as possible. For instance, no one will suffer if scatter, unscathed, scoop, etc. reemerge as skatter, unskathed, and skoop. The distinction between sc– and sk– is artificial and easy to abolish. Along the same lines, dunghill will smell as sweet if it loses the last letter. So my proposal resolves itself into the following: begin with the most innocuous changes and stop for about ten or fifteen years. Then go on. The proposed reform should resemble a multilayer missile, because the public will not accept a revolution. For starters, bild for build is fine, but bery for bury is not. Consequently, I propose to draw up a list of changes, beginning with the ones that will not irritate too many opponents, go on slowly, and then (possibly!) strike where the change looks truly radical.

Forget all plans that suggest an introduction of diacritics and new letters.

However time-consuming the task may be, before the congress is convened, the Society needs a plan thought out from beginning to end; it should include all the words whose spelling will be changed.

The congress will achieve nothing unless at the preparatory stage it ensures the support of those in whose power it is to implement the reform.

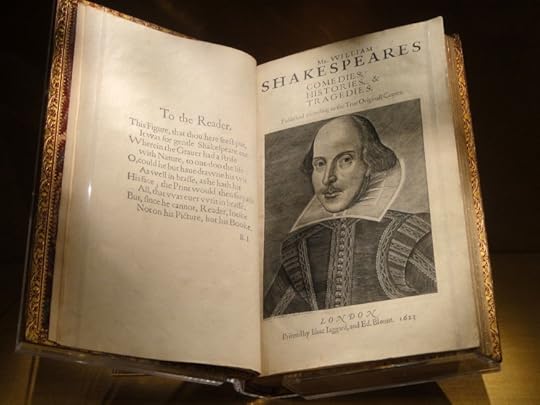

This is a page from Shakespeare’s Folio. Its spelling and misspellings are vastly different from ours.

This is a page from Shakespeare’s Folio. Its spelling and misspellings are vastly different from ours.The less we talk about general principles, the better. A brief reminder of what I mean.

“History will be effaced.” The etymology of English words will not fall victim to the reform. To begin with, etymology is not worth rescuing when it comes to the spelling of a modern language, and, which is more important, the spelling of numerous words that pretends to reflect the past is a monument to ignorance and does not preserve the true history of English.

“Many homographs will appear.” There are already hundreds of them, and there are hundreds homophones, but context disambiguates them.

“People will be confused.” Any change confuses people, but nothing can be more confusing than the spelling we now have.

“Millions of books will have to be reprinted.” Not at all! Especially if the reform takes time, readers will gradually get used to the novelty. Anyway, most of us read book in new editions and reprints. Consult Shakespeare’s folios (facsimile editions are easily available) and compare them with what stands on your shelf. English spelling has changed dramatically since the days of the early seventeenth century, but English culture has not suffered as a result.

Spelling reform has been implemented in several major European languages. Protest has always been vociferous, but there have been no casualties.

However, let me repeat: if the congress takes place, the focus should be on practical matters more than on the defence/defense of the reform, though some introduction on the predictable objections is naturally needed.

Finally, what do you think of the passage I have abstracted from a letter published by The Academy, July 17, 1915, p. 44, at the height of World War I?

“I want to see the grait and needless waste ov time and muny on teeching children to reed ended, and that speedily, espeshaly when there iz such an outcry for economy. Let us proov our sinserity in this crusade for thrift and carefulness by permitting teecherz to uze a sistem of speling which duz not waste time, duz not reezon at defians, nor disregard both history and etimolojy. Adults may spel, doutless will continue to spel, acording to the old fashon until the end ov the chapter. As Lord Haldane says—they ar too slugish to change, unles they wer taxt for every redundant letter emploid, the history, etimolojy, fashon, rithm, poetry ov wurds, wud fly to the windz. It is to the yung and the future, we need to giv attenshon.”

Smaller issues

These are crêpes. From an ad in a grocery store: “Crispy crust w/chewy, tasty insides.”

These are crêpes. From an ad in a grocery store: “Crispy crust w/chewy, tasty insides.”Mainly Romance

Where is d in French aventure, as opposed to Engl. adventure? It died. In Middle French, in a combination of two consonants, the first one was regularly lost.

Is the etymology of crêpe given in the OED correct? Yes, it is. The Old French adjective was crespe. In the groups of two consonants the first one was lost (see above), and in the stressed syllable the vowel was lengthened (so-called compensatory lengthening). The circumflex over ê is the reminder of the lengthening (obviously, today no one needs it, but spelling is needlessly archaic not only in English). The Latin etymon was crispus (cf. Engl. crisp). To prove the validity of this etymology, it is enough to observe that in Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese the word still sounds as crespo. Crêpe ~ crape “fabric” is an etymological doublet of crêpe “cake.” In Modern French, the two homonyms are grammatically distinct: the first is feminine, while the second is masculine.

There was a question about the etymology of conscience and awareness. Neither word poses problems. Conscience, a thirteenth-century borrowing from French, is clearly con + science, so it refers to one’s inner knowledge of things, one’s inmost thoughts. The present day sense is late. By contrast, aware is of Germanic origin (compare German gewahr, the same meaning, as well as Engl. beware and wary). Aware is related to neither war, which is of French origin, nor the root of awaken.

Can Engl. fox be related to Latin focus? Since both f and k coincide in the two words, fox cannot be a cognate of the Latin noun, while the borrowing of focus “hearth, fireplace,” with reference to the color of fire, as an animal name is quite improbable.

This is hubbub indeed.

This is hubbub indeed.Germanic and Celtic

Question: “I came across the following in Henry David Thoreau’s ‘A Plea for Captain Brown’: ‘Their great game is the game of straws, or rather that universal aboriginal game of the platter, at which the Indians cried hub, bub!’ Could the North American aboriginal expression be the origin of the word hubbub?” No. the English word was recorded in the sixteenth century, and its derivation from an Irish war cry is, most probably, correct. But the coincidence is not fortuitous: both exclamations are the product of the same impulse, and such words are sometimes universal.

A colleague called my attention to the fact that in my brief answer about the origin of OK, I should have mentioned the playful spelling oll korrect (1839), which is allegedly the true source of OK. The association with Old Kinderhook goes back to 1840, for only Van Buren’s 1840 presidential campaign made the word famous. Oll korrect has often been mentioned in the investigation of OK, and everything may have begun with this facetious misspelling. See Allan Metcalf’s book OK: The Improbable Story of America’s Greatest Word.

To conclude

The remarks about Latvian are apt! Most etymologists, unless they are specialists, cite words found in dictionaries and secondary sources. They rarely know the “non-major” languages to which they refer. This is also true of my recourse to Latvian. I can read linguistic literature in Lithuanian and, to a certain extent, in Latvian, but of course have no “feeling” for either.

Many thanks for pointing to Gąsirowski’s articles. I happen to know both (and many of his other works). My Bibliography of English Etymology features only one of them, but since its appearance the database has increased by about 4000 titles. With regard to books and articles, all advice is precious, for nothing is easier than to miss important publications on the subject in hand.

Image credits: (1) First Folio in the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC. Photo by Daderot. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Crêpes con la Nutella. Photo by Dawid Skalec. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Stags Fighting 3. Photo by MrT HK. CC BY 2.0 via mrthk Flickr.

The post Etymology gleanings for March 2016 appeared first on OUPblog.

Is it all in the brain? An inclusive approach to mental health

For many years, the prevailing view among both cognitive scientists and philosophers has been that the brain is sufficient for cognition, and that once we discover its secrets, we will be able to unravel the mysteries of the mind. Recently however, a growing number of thinkers have begun to challenge this prevailing view that mentality is a purely neural phenomenon. They emphasize, instead, that we are conscious in and through our living bodies. Mentality is not something that happens passively within our brains, but something that we do through dynamic bodily engagement with our surroundings. This shift in perspective has incredibly important implications for the way we treat mental health – and schizophrenia in particular.

In much of the Western world, and particularly in the United States, drugs are a primary mode of treatment for psychological disorders. This reflects the common assumption that mental illness results from faulty brain chemistry. Although it would be difficult to deny that medication can play an important role in treatment, this drug-based approach faces three major limitations:

It is doubtful whether disorders such as schizophrenia are caused by anything neurological (in the straightforward way that heart attacks are caused by arterial blockage). Indeed, many mental, emotional, and behavioural problems do not have clear-cut genetic or chemical causes, but instead result partly from difficult human experiences, stressful events, or other problems in their personal life. When minds “go wrong” it is not simply a matter of mechanical breakdown, and “fixing” neural wiring will not be sufficient to address the underlying causes of disorder.

Image Credit: ‘Stickney Brook Yoga’ by Matthew Ragain. CC BY SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: ‘Stickney Brook Yoga’ by Matthew Ragain. CC BY SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.There is evidence that antipsychotic medications are not sufficiently effective in managing the debilitating symptoms of schizophrenia, such as delusions and hallucinations. Many patients on medication continue to experience psychotic symptoms throughout their lifetimes. In addition, there is a worry that anti-psychotic drugs may cause negative side effects, such as apathy, muscle stiffness, weight gain, and tremors.

By focusing on just one organ of the body (i.e. the brain), drug-centred approaches overlook the role of bodily processes more broadly construed. Once we acknowledge that consciousness and cognition are fully embodied, this pushes us to move beyond narrowly defined, brain-based methods and to seek treatments that transform a subject’s overall neurobiological dynamics.

What can be done?

Interventions that target the subject’s whole body, and not just the brain, include yoga, dance-movement therapy, and music therapy – all of which have proven to help schizophrenic subjects re-inhabit their bodies and regain a coherent sense of self.

There is strong evidence that yoga therapy can reduce psychotic symptoms and improve the quality of life of adults with schizophrenia. Through the repeated execution of sequenced movements and postures, as well as enhanced sensory self-awareness, subjects are able to forge more of a felt connection with their bodies and also begin to feel more “at home” in their surroundings. Breathing exercises and meditation can help to make the make body feel more familiar, increase sensitivity to subtle bodily sensations, and minimize feelings of bodily alienation and hallucinations that are commonly found in schizophrenia.

Image Credit: ‘Contact Improvisation’ by Davidonet. CC BY SA 2.0-FR via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: ‘Contact Improvisation’ by Davidonet. CC BY SA 2.0-FR via Wikimedia Commons.Like yoga, dance/movement therapy centres on the use of movement to foster the integration of bodily sensations and emotions. Through exercises that aim to increase bodily self-awareness (such as sequential warm-ups, patting one’s own body, defining its outer limits, grounding, and reflecting on the movements of others), a sense of self is promoted. In addition, it provides opportunities for increased emotional expression and the controlled, cathartic release of emotions of joy, sorrow, rage, or frustration.

Last, but not least, music therapy may have great potential for treating schizophrenia. Subjects can be invited to play or sing, whether through improvisation or the reproduction of songs, or simply listen to recorded or live music. Like dance, music provides subjects with a nonverbal means of expression and can serve as a powerful therapeutic medium for those who are unable or too disturbed to rely on words. Improvising, playing, composing, and listening to music all are thoroughly embodied processes that address symptoms from the bottom-up, by engaging emotions and bodily feelings.

By tackling mental issues with this ‘bottom-up’ method, we are able to bring about changes in higher-level cognition and interpersonal functioning – by evoking emotion and tapping into bodily feelings. Such therapies have a fantastic potential to make subjects more attuned and sensitive to their surroundings, and to foster emotional resonance with others.

It is true that such treatments may take longer, and be more expensive than medication. However, such interventions may be our best hope for bringing about lasting improvements – focusing on the person as a whole, to treat a problem as a whole.

Featured Image Credit: “Contemporary Dance at its Finest,” by Nazareth College from Rochester, NY, USA – Bend and Snap Uploaded by Ekabhishek. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Is it all in the brain? An inclusive approach to mental health appeared first on OUPblog.

The IMF and global exchange rates: dissensus in Washington

In many scholarly and activist circles, the International Monetary Fund (IMF, or ‘the Fund’) has a reputation as a global bully. The phrase ‘Washington consensus’ has come to invoke a rigid orthodoxy of austerity and liberalization which the Fund, along with its cousins the World Bank and the US Treasury, imposes on developing countries. As an organization, the IMF is seemingly monolithic, drawing comparison to the Vatican even amongst its own staff.

Close observers of the global economy recognize that matters are considerably more complex, but even so there has been relatively little study of internal debates at this highly disciplined organization. For this reason, I was drawn to a curious area of dissensus and ambivalence on a critical issue of global financial governance. The area in question is the Fund’s policy regarding exchange rate regimes in developing countries. While seemingly obscure, exchange rates are critically important to the global economy. During the 1990s, a series of developing and post-Communist countries experienced financial crises that began with a collapse of their exchange rate regime. The IMF played a central role, prescribing policy solutions that drew substantial criticism. But while the Fund had clear prescriptions on issues like trade openness, privatization, financial liberalization, and budget balance, they didn’t have a policy to speak of on the exchange rate question. This is particularly perplexing because overseeing the international monetary system was precisely what the Fund was created to do.

A key question facing many developing countries is whether to ‘float’ their currencies (allow them to adjust to market forces) or ‘fix’ them to a major currency, such as the U.S. dollar. Examining recently declassified IMF documents, I found that this question had begun to cause substantial internal friction within the Fund by the early 1990s. In particular, while the United States government favored a policy of promoting currency flexibility, several European countries (most notably France) opposed this preference. In an effort to avoid antagonizing these constituencies, the Fund’s staff economists formulated an ambivalent and ad hoc policy that came perilously close to ‘anything goes.’

This ambivalence proved to be a liability in the latter part of the decade, as countries repeatedly fell to currency crises. In many of these cases, countries had adopted a ‘peg’ to the dollar (that is, the local currency remained roughly constant vis-à-vis the dollar as a matter of policy.) Many economists knew that these policies were inherently vulnerable, but the Fund did little to raise concerns. For example, less than a year before the collapse of the Mexican peso in 1994, the Fund’s Executive Board voiced support for the policy (at a time when prominent international economists were already raising concerns.)

Image credit: IMF Headquarters, Washington, DC by International Monetary Fund. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: IMF Headquarters, Washington, DC by International Monetary Fund. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.After a wave of crises in 1997 and 1998, IMF leaders realized they had a problem. The response was, finally, something that looked like a clear policy. Fund officials now promoted something called the ‘bipolar view’; according to this policy, most developing countries faced a stark choice between a fully ‘floating’ currency and so-called ‘hard pegs.’ The latter meant ‘locking in’ a fixed exchange rate, as Argentina did when it adopted a law that fixed its currency to the dollar, by law, at a one-to-one rate. The problem? Argentina’s financial system imploded in 2001, in large part because of this peculiar system. The IMF had gone from deep skepticism towards this kind of policy, to endorsing and even advocating these ‘hard pegs’. In both Russia and Brazil, Fund officials pushed national policy-makers to adopt this approach, something which (with the benefit of hindsight) would have been catastrophic.

In short, the IMF switched from an ambivalent and hands-off posture to the ill-fated ‘bipolar view’, which was clear but hardly sound advice. While this ‘bipolar’ policy had the support of senior Fund managers, it was eventually vetoed by the IMF’s senior body, the Executive Board. What is the explanation for this ‘Washington dissensus’?

I found two interrelated explanations. The first was that the economics profession, the source of the Fund’s legitimacy and expertise, was itself deeply divided. While some economists are ardent advocates of currency flexibility (such as free-market guru and Nobel Prize winner Milton Friedman), others (most notably the also Nobel Laureate Robert Mundell, sometimes referred to as ‘father of the Euro’) said the opposite. As a result, the Fund’s staff had very little ability to present the policies they advocated as backed by credible expertise. Second, the wealthy and powerful countries that ultimately control the Fund were themselves divided. European countries which make up a substantial percentage of the Fund’s Executive Board were in the midst of their own monetary experiment (the creation of the Euro), and tended to interpret the challenges facing developing countries in light of their own experience. Several countries, such as France, were strongly opposed to establishing a blanket preference in favor of currency flexibility, as the United States favored. This was a bit of international monetary rivalry that goes back decades to de Gaulle’s famous complaint that the international role of the dollar was an ‘exorbitant privilege.’

In short, in this critical area of governing the international monetary system, the IMF was in a stalemate: European countries could block the organization from taking the US-favored line (which was also closest to that of the Fund’s staff economists), but they couldn’t provide an alternative. When the Fund’s leaders attempted to forge a compromise, the result was a Jerry-rigged improvisation that pleased no one. The result was ambiguity, ambivalence, and inconsistency in an organization famed for its rigor and discipline.

So what’s the lesson in all this? Governing the international economy is a problem of coordinating individuals, organizations, and countries with diverse interests and ideas. Often crises result not from the actions of any particular group doing the ‘wrong thing’, but because everyone’s actions add up to a mutually inconsistent, contradictory whole. This is an important lesson to bear in mind as policy-makers around the world attempt to prepare for the next financial crisis – which is sure to come.

Headline image credit: Exchange Money Conversion to Foreign Currency by epSos.de. CC-BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The IMF and global exchange rates: dissensus in Washington appeared first on OUPblog.

Interviews with historians: An OAH video series

At the 2015 Organization of American Historians conference in St. Louis, we interviewed OUP authors and journal editors to understand their views on the history discipline. Gathering at the OUP booth, scholars – working in fields ranging from women’s history to racial history, cultural history to immigration history – discussed topics both professional and personal. As we gear up for this year’s conference in Providence, RI, we’re revisiting our conversations in the video series below, and we hope you’ll join the conversation online and at the OUP Booth.

What is the one word that all historians should be thinking about today?

What advice do you have for graduate students?

What role should historians play in conversations about contemporary issues?

How do you confront taboos in your scholarship?

How do historians get started on a new project?

What’s your position? Let us know in the comments or by tweeting @OUPAmhistory.

Featured image credit: The St. Louis Arch by Baylor98. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Interviews with historians: An OAH video series appeared first on OUPblog.

March 29, 2016

Hamilton the musical: America then told by America now

It was only after I finished writing The Founding Fathers: A Very Short Introduction that I got to see the off-Broadway version of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s “Hamilton: An American Musical” at New York City’s Public Theater. I was lucky enough to see the Broadway version (revised and expanded) last month.

Like many colleagues in early American history (the colonial period through the age of Andrew Jackson), I was entranced by the play. Miranda has pulled off something approaching a miracle — retelling the complicated and dramatic life of Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804) in a Broadway musical, drawing on genres of music and theater from classic show tunes to hip-hop, Britpop, and epic rap battles, delivered by an immensely talented, energetic, multiracial cast.

Beyond its theatrical success, Hamilton is having an astounding cultural impact at least equaling anything we know in the history of theater. My colleagues and I hear reports that students in elementary and middle schools know the words and the music, and perform numbers from the show at the drop of a hat. Catchphrases from Hamilton have entered modern dialogue, such as “I’m not throwing away my shot!” and “Immigrants: we get the job done.” And the show’s use of multicultural casting resonates in our current discussions of immigrants and the tangled racial and ethnic history of our nation and its politics.

Though some scholars quibble about historical details, I argue that Hamilton is “Shakespeare history” — historical dramatization remaining true to the substance of the past while condensing and shuffling chronology for dramatic effect. Three major things contribute to its success at presenting the substance of Hamilton’s life and the complex origins of the American nation.

First, the cast — both the people assembled and the principle of casting. Hamilton features a multiracial cast, with, for example, such figures as George Washington, the Marquis de Lafayette, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Aaron Burr, and Angelica Schuyler being portrayed by African-Americans and such figures as Hamilton himself, John Laurens, and Philip Hamilton being portrayed by Latino actors. It is also a nice touch that the only Anglo role is that of King George III. This method of casting presents the story in a form engaging the sympathies and interest of a modern American theater audience. Multiracial casting helps an audience of any racial makeup to connect with these historical figures as they contend with challenging political questions having relevance and bite today; they thus get beyond stale generalizations about “dead white men.” In fact, two of the most remarkable sequences in Hamilton present key decision points of the Washington administrations as heated rap battles between Hamilton and Jefferson.

Second, the show’s careful attention to the politics of the era. The rap battles mentioned above do a splendid job of plunging audience members into knotty issues of politics, diplomacy, and governance. Miranda has noted in many interviews that rap is an especially efficient means of giving an audience a great deal of information in easily-absorbed form. Rap also captures the rhetorical richness and virtuosity of the era and its people; these men and women were skilled in debate, and their words matter now as they did then.

Third, the show’s commitment to take politics and government seriously, and with respect. As teacher and librarian Danielle Lewis noted after seeing Hamilton, the show teaches us (without doing so in a heavy-handed way) that “the Constitution placed faith in the people, and that faith has not been misplaced — it is up to ‘we the people’ to make sure that that faith has not been misplaced.” Indeed, in a time when far too many Americans reflexively mistrust politicians and fear government, Hamilton tells a far different story, one that all Americans should hear and ponder. This story is that the founding fathers, including Hamilton, sought to order the nation’s political world with words by creating a form of government (set forth in the Constitution) that they hoped would respond to the nation’s problems effectively while protecting individual liberty. Those fortunate enough to see Hamilton will learn that that creation was not fore-ordained, and that the founding fathers were taking great chances, sometimes risking their lives in the service of their ideals and their political commitments.

Had I had the chance to include Hamilton in The Founding Fathers: A Very Short Introduction, I would have used it to illustrate the continuing power of the founding fathers over the American imagination — as Mr. Miranda has put it, America then told by America now.

In the late 1960s, the musical 1776 (which is returning to Broadway this spring) dramatized the creation of the US Declaration of Independence, with singing and dancing John and Abigail Adams, Thomas and Martha Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin. In the years since its debut, the musical has inspired many scholars — including the present writer — to study early American history, because 1776 made these historical personages seem real and human. Who knows how many young scholars will be drawn to the study of Hamilton and his contemporaries because of their exposure to Hamilton: An American Musical?

Headline Image: Quill & Ball. Photo by Delwin Steven Campbell. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Hamilton the musical: America then told by America now appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers