Oxford University Press's Blog, page 530

March 26, 2016

Word in the news: Mastermind

In a speech made after the November terrorist attacks in Paris, President Obama criticized the media’s use of the word mastermind to describe Abdelhamid Abaaoud. “He’s not a mastermind,” he stated. “He found a few other vicious people, got hands on some fairly conventional weapons, and sadly, it turns out that if you’re willing to die you can kill a lot of people.”

Why did Obama single out this particular word? What in its history and current use make it a problematic term?

The first masterminds

To find out, we need to go back to the 17th century. Currently, the first citation for mastermind in the Oxford English Dictionary is John Dryden’s play Cleomenes, of 1692: “A Soul, not conscious to it self of Ill, Undaunted Courage, and a Master-mind.” Here, and for nearly 200 years to follow, the term was solely a positive one, used to describe “a person with an outstanding intellect.” In 1720, in his translation of the Illiad, Alexander Pope chose it to describe Vulcan’s creation of the Shield of Achilles, reflecting the noble, godlike associations of the word, and tying it to the concept of creative genius: “There shone the image of the master-mind./There earth, there heaven, there ocean he design’d.”

It is not until 1872 that the word is recorded with any negative connotations. In Anthony Trollope’s novel The Eustace Diamonds, Lord George de Bruce Carruthers complains that “up to this week past every man in the police thought that I had been the mastermind among the thieves,” giving the term its first whiff of criminality. A new meaning was established, namely: “a person who plans and directs an ingenious and complex scheme or enterprise” – and came to be strongly associated with wrongdoing.

This new meaning did not eclipse the “outstanding intellect” sense, however, with both uses well evidenced throughout the 20th century. Today, the term continues to be used in positive, admiring contexts, including the long-running British quiz show Mastermind (1972-present). Our language databases show numerous modern examples where it describes creative genius, such as the filmmaker who “is a mastermind, and only does something if its better or different than his last piece”; the musician who is “the creative mastermind behind this album”; and the writer of a successful TV series who is described as “the mastermind behind this masterwork of a show.”

Positive or negative?

One of the problems Obama was referring to with this word, therefore, is its continued positive associations – it is used to describe exceptional people, who have produced great creative works, and is therefore – he suggests – not appropriate to describe a terrorist. Despite this positive sheen, the term has become strongly linked to criminality. The Oxford English Corpus shows that the words most associated with mastermind are a felonious group – criminal, terrorist, and evil are among the most common types of mastermind in our databases, and they are most usually found attacking, plotting, and bombing. Alleged and suspected masterminds are also extremely common, demonstrating that the word is a favourite of news reports. Indeed, the term could be described as part of the shorthand of journalese – and it comes as no surprise that it appears more than twice as often in news reports as it does in any other type of writing.

The other realm in which mastermind is commonly found is that of film. The diabolical mastermind (another common collocation on the Oxford English Corpus) is a caricature familiar from hundreds of spy and action movies. That we choose this word to describe people who commit acts of terror in the real world is both unsurprising and unsettling. Most people are only able to process acts of extreme violence in terms of what they have seen on the screen – it is common, in the wake of attacks or disasters, to hear the people involved describe what has occurred as “like something from a film.” In the same way, the people responsible for such acts of violence – the terrorists – are associated with Hollywood supervillains. It is easier to frame these people as fictional, one-dimensional, “evil” characters, than to see them as mere humans, and attempt to understand their actions on that basis. The world of films is clearer cut, more black and white, less troubled by moral ambiguity.

This association with Hollywood also gives mastermind a kind of glamour, a certain desirability. Two other phrases commonly seen in the Oxford English Corpus are self-proclaimed mastermind and self-described mastermind. Clearly, this is a label that certain people wish to attach to themselves, despite – or, perhaps in some cases, because of – its association with notorious terrorist acts. It glorifies the people behind these acts, placing them on a pedestal alongside the invincible criminal geniuses of fiction and film.

Which word to use instead?

So what are the alternatives? Ringleader has been suggested, and has been seen in several recent newspaper reports of terrorist activities. Defined as “a person who initiates or leads an illicit or illegal activity,” this is more transparently negative, and is rarely used as a “self-proclaimed” label in the way that mastermind is. Commander is another alternative, though this word’s associations with organized military leadership may raise objections to its use to describe terrorists. A more neutral alternative is organizer, which the Oxford English Corpus shows is used in a range of contexts, from festivals and conferences to protests and raves.

Of course, there is no perfect choice. No words are truly neutral (if neutrality is even what we are seeking) or, for that matter, wholly positive or negative. Words are fluid: they do not exist in isolation, but gain their meaning from the contexts in which they are used, and the associations they gain from them. Those associations have the power to make us feel a certain way – fear or courage, unity or discord. And that power is ours, in the words we choose to describe and explain the often incomprehensible events around us.

A version of this post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Featured Image: “Ambassade de France US – Barack Obama – Condoléances Charlie Hebdo” by the White House. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Word in the news: Mastermind appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know 21st-century Shakespeare? [quiz]

You may know Christopher Marlowe and Richard Burbage, The Globe Theatre and The Swan, perhaps even The Lord Chamberlain’s Men and The Admirals’ Men. But what do you know of modern Shakespeare: new productions, new performances, and ongoing research in the late 20th and 21st centuries? Shakespeare has, in many ways, remained the same, but actors, directors, designers, and other artists have adapted his work to suit the needs of the world and audiences today. From digitization to globalization, how much do you know about contemporary Shakespeare?

Featured Image: “House Seats” by Canon in 2D. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

The post How well do you know 21st-century Shakespeare? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know David Hume? [quiz]

This January, the OUP Philosophy team has chosen David Hume as their Philosopher of the Month. Born in Edinburgh, Hume is considered a founding figure of empiricism and the most significant philosopher of the Scottish Enlightenment. With its strong critique of contemporary metaphysics, Hume’s Treatise of Human Nature cleared the way for a genuinely empirical account of human understanding. His work is still influential today.

But how much do you know about this famous Scottish philosopher? Test your knowledge of David Hume in the quiz below.

Quiz image credit: Portrait of David Hume, by Allan Ramsay, 1766. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: Nature photo by hilk. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post How well do you know David Hume? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

March 25, 2016

What is cancer drug resistance? Q&A with Dr Maurizio D’Incalci

One of the biggest obstacles in treating cancer is drug resistance. There are still many unanswered questions about the genomic features of this resistance, including different patient responses to therapy, the role drug resistance plays in the relapse of tumours, and how cancer treatments in the future will combat drug resistance. One doctor at the forefront of ovarian cancer research is Dr Maurizio D’Incalci, who answered some of the important questions for us about this serious issue in oncology.

What is chemotherapy drug resistance?

Antineoplastic resistance, or chemotherapy resistance, is the ability of cancer cells to survive and continue to grow despite being treated with anti-cancer therapies.

How does this drug resistance develop?

Chemotherapy kills the drug-sensitive cells within the tumour, but leaves a proportion of drug-resistant cells behind – meaning that when the tumour begins to grow again, chemotherapy may fail because the cells are now resistant.

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is one example of a cancer type which experiences drug resistance. EOC is generally sensitive to platinum-based chemotherapy, and the vast majority of patients respond to platinum-based therapy after debulking surgery, a process in which part of the malignant tumour is removed. Unfortunately, more than 80% of these patients relapse with a progressively resistant disease, and tend to die within five years of diagnosis.

Why is it important that we understand more about the genetic make-up of tumours?

The relationships between molecular characteristics of tumours, patient outcome, and patient responses to therapy are still unknown. Studies performed so far in large cohorts of patients, at both the genetic and epigenetic level, have failed to provide reliable biomarkers, or specific genes, which can help us to improve patient classification. We also cannot identify the genomic alterations which are critical for the development of a targeted approach against EOC and other types of cancer.

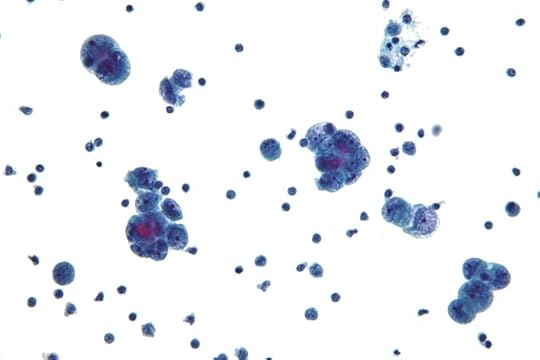

“Micrograph of serous carcinoma, a type of ovarian cancer, diagnosed in peritoneal fluid” by Nephron. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Micrograph of serous carcinoma, a type of ovarian cancer, diagnosed in peritoneal fluid” by Nephron. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.In addition, there is currently no molecular information available on tumour biology at relapse, as secondary debulking surgery for epithelial ovarian cancer is only performed in a small fraction of patients who relapse. Therefore, we do not know whether the molecular scenario connected with tumour relapse mirrors the initial tumour tissues.

What were the key findings in your study on profiling cancer gene mutations?

Our study took advantage of a unique tumour tissue collection of more than 1,700 frozen tumour biopsies collected over the last 20 years. In this biobank there were a few cases in which biopsies were taken both before any therapy or after some lines of chemotherapy when the recurrent disease was less sensitive to treatment. The study shows two key findings to be taken away. There is a less than 2% concordance between the primary tumour and the recurrent disease – demonstrating the wide variations between initial occurrence of the cancer, and the subsequent regrowth. Secondly, the genetic make-up of the relapsed disease is less diverse than the primary disease. Alterations in the initial tumours do not accurately reflect those that are present at relapse, and this has potential implications for prognosis and treatment.

How are cancer treatments going to develop in the future to combat drug resistance?

Understanding the relationship between the initial tumour and the relapsed tumour is an important step in the solution to chemotherapy drug resistance. Until now, important choices regarding treatment have been made by looking at the initial tumour, when in fact the relapsing disease, which is resistant to the chosen therapy, may have evolved in a completely different direction. This is initial proof that longitudinal biopsies – the continual observation of the same patients over a period of time – could be useful for the clinical management of epithelial ovarian cancer.

Featured image credit: ‘Granulosa Cell Tumour of the Ovary, CEA Immunostain’ by Ed Uthman. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What is cancer drug resistance? Q&A with Dr Maurizio D’Incalci appeared first on OUPblog.

When’s Easter?

The phrase “moveable feast,” while popularized by Ernest Hemingway’s memoir, refers primarily to the holidays surrounding Passover and Easter. Although “Easter” is not a biblical word, Passover is a major holiday in the Jewish calendar. The origins of the festival, while disputed among scholars, are narrated in the biblical texts in Exodus 12–13, describing the Israelites who are anxious to escape slavery in Egypt, preparing a special meal on the night the “destroyer” slays the first-born of the Egyptians. (The theological implications of this, naturally, weren’t lost on early Christians.) So, when did this happen?

Without delving into the sticky issues of historicity, Judaism eventually fixed the date of Passover on Nisan 15 and here’s where it starts getting fun. The ancient calendar of Judaism isn’t fully understood. The Bible doesn’t lay it out in detail (presumably people of the time knew their own time-keeping) and the debate still continues. Generally the biblical calendar gets classified as lunisolar—lunar with elements of solar, or perhaps vice-versa. The date of Passover depends on the full moon, more precisely it begins on the first full moon after the vernal equinox. Easter, in the Christian adaptation, is the first Sunday following the full moon following the vernal equinox. Follow?

As a result of this calendrical conflation, Easter may fall as early as March 22 or as late as April 25. But wait—this is according to the calendar used by the Roman Catholic and most Protestant Churches. Eastern Orthodox Christians base the date of Easter on the Julian calendar, not the Gregorian calendar used by Western Christians. So, when is Easter?

This question lies behind a recent initiative raised by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby. As the head of the Anglican Communion, Archbishop Welby has engaged in talks with Pope Francis, Bartholomew I, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, and Pope Tawadros II, leader of the Coptic Church in Alexandria, in an attempt to set a fixed date for Easter. The moveable feast would finally be as predictable as Christmas.

A story on BBC News earlier this year outlines Archbishop Welby’s lead on the issue. The Vatican has, in principle, agreed to have a fixed date for Easter. However, challenges may lie further east, as the Orthodox Church is ran under an autocephalous status with no single leader of “Orthodox Christianity.” Issues revolving around the choice of calendar have deep roots. Such issues are often tied to religious identity. If the Orthodox Church doesn’t join in, the attempt to fix a date can meet only partial success.

Even more complicated are the implications for Protestants. Some estimates put the number of distinct Protestant groups into the tens of thousands. Although times change, the early breaks between Roman Catholicism and, particularly reformed traditions, fell along rather strong party lines. Would all major Protestant groups be willing to shift their calendars? Should Rome, Canterbury, Constantinople, and Alexandria agree? Right now most Protestants follow Rome for the date of Easter.

What about those beyond the church? After all, not only are religious celebrations impacted, but many school calendars and business interests as well. If the date’s going to change, a lot of people have to be on board.

A culture of convenience, however, may ease the issue, should the major liturgical traditions agree. Wouldn’t it be easier to make spring-time plans if the date of Easter could be fixed? Not to worry that we don’t know the date of Jesus’ crucifixion—we don’t know the day he was born either. Ironically, history is perhaps the least determining factor in such discussions.

Undoubtedly a permanent date for Easter would be a much easier discussion if the Bible stood behind Easter as a holiday. Like the argument that “the King James Bible was good enough for Jesus and Paul,” the date of Easter going back to the time of Jesus is anachronistic. Evidence for a full celebration of Pascha, the early name for Easter, dates to at least a century after the event it commemorates. Complicating matters even further is the fact that Passover and Easter fall into the very old and very pagan set of equinox celebrations. Easter isn’t just a Christian idea; scholars suggest Passover may go back predating biblical traditions as well.

The Bible has its share of holidays, Passover among them; while the New Testament provides no authoritative dates for events surrounding the life of Jesus of Nazareth. The date of Christmas wasn’t established until the fourth century. Even 17 centuries later we continue to ask, “When’s Easter this year?”

Cover image: Easter Procession, 1893 by Illarion Pryanishnikov. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post When’s Easter? appeared first on OUPblog.

Three Cuts

Songs leave unique imprints on people and places. In India, especially, songs from films offer a multitude of trajectories for anyone who is more than deferentially familiar with them, contained in or limited by larger prospective areas of film study material. Film songs form a major portion of its popular culture; hence, they are etched into individual and collective memories weaving unique tapestries of such imprints. As there are growing studies of Indian song production and consumption, I see myself having travelled across these trajectories, my memories of them intersecting my local, national, and global journeys. Songs and singers have a great capacity to intrigue and enervate you, charm and choke you, with their virtuosity and subtle (and sometimes loud) communication. The following three cuts are a reflection of such subjective encounters, many of which have long stayed buried without articulation. Here they are hoped to take one on a short journey of three very different experiences linked to three songs in Hindi, Telugu, and Bengali languages. Their evocative and perhaps provocative potential, as linked, montaged yet aggregated experience of an aural cinema, is a good starting point to learn more about Indian film songs.

First Cut

A rare Lata Mangeshkar song. That’s what it was. I had never heard it before.

But, when my father played it on a Sony multi-player on a late evening, it became a discovery — one of the many songs of the great singer of the subcontinent. It was a lullaby. A few weeks prior to this event, it was played on Chaya Git (10 p.m.) (or Aap ki Farmayish at 10.30 p.m.), a programme that broadcast Hindi film songs – often, the old ones — on Vividh Bharti, to which my father listens avidly. And, on his first encounter with the song, he was in near tears.

His Geminian curiosity put him on a quest for the song; as a retired employee of All India Radio, it wasn’t tough for him to talk to his (retired) colleagues at Vivid Bharti and track the song through their friends to Mumbai’s station. So, soon, there it was, a CD arriving at his doorstep. He clung to it dearly and played it many times, one of which was my visit to him.

I had never heard anything more magical. It was a song composed by Brij Bhushan (Kabra) for the film Pathan (1962), the Hindi lyrics penned by B K Puri. That day, listening to the song I again wondered what that ‘Lata-Mangeshkar-quality’ in Hindi popular film music was all about. Mesmerising. It is something that one is so accustomed to, feel comfortable with; it’s like taking sanctuary under a thick mango tree on a summer day. Even then, you never know what is in store for you until ‘it’ finds you, throws you off guard and makes you carry an imprint of it to the end of all experiences. It is just an experience of, somehow, coming home.

Second Cut

If you lived on the east coast of North America, you’d know how blizzards hit you. And if you passed through one, or just reached home in time only to wake up the next morning to let in a pile of powdery snow through the threshold, then you knew you had it for the day. But, the fun part is when you play old Indian film songs on the system, cooking rice or parathas, and wondering what you’re doing with your life in snow there, you end up singing the song that’s playing on the system. How frequently you sing such songs, and how many, is a different story. You’re perhaps not thinking about songs but about mending those thick, unmusical boots to wear for work the next day. That’s the life of a person straddling two landscapes and two cultures.

On one such occasion, a group of us travelled from Toronto (I was doing my MFA at York University in Toronto) to New York, and to Boston, around the start of the new millennium. There was a big blizzard awaiting our arrival, but we drove through Boston listening to some old Telugu film songs. And what fun it was! Neither the faces outside nor the words of the song had anything to do with each other. We shopped for Indian vegetables somewhere close to Cambridge, cooked an elaborate Indian meal, ate, drank, and finally agreed, along with a television channel, that Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” was the best and most popular number of the previous century as we chimed our destinies into the new millennium. Pop music? In India? I cannot decide who the best singer can be when I think about it. But I know one thing. That almost all singers sang at least one ‘English song-like number’ — something that had a waltz tempo, and some tune that had an everlasting appeal. You don’t need to know the words to listen to them. So on a blizzard afternoon, you can listen to an English song in your mother tongue like this one. (Well, you can listen to it even when there is no blizzard).

http://www.surasa.net/music/lalita-gitalu/rbs_films/mallepulu.mp3

The song was from a 1954 Telugu film Raji naa Pranam (Raji, My Life), sung by R Balasaraswati to a tune composed by S. Hanumantha Rao, whose filmic output is very small. Perhaps this was the only film he scored music for. I’m not sure.

Third Cut

Indian film songs are the most mobile these days. Imagine what life would be without the Internet, and if you cannot play a “Thriller”, a Telugu, Bengali, or Hindi film song of rarity to ‘just listen to it once’. Technology too brings blizzards. Perhaps it brings so many of them, there is so little time to appreciate all…

The only one I remember, sitting in India, on a warm afternoon in Bangalore, is the one of the turn-of-the-millennium. That blizzard is somehow about identifying “Thriller”, and through it, remembering so many other songs that have no connection to Michael Jackson. This summery afternoon brings to my mind, as I write this, a beautiful Bengali song of Sandhya Mukherji that Salil Chowdhury so effortlessly composed. Ask any Bengali friend for its meaning.

The world remembers the best numbers in a certain way; you can remember your songs by playing on YouTube reverentially without consigning them to the crushing feet of time, especially those little gems tucked away in beautiful voices unknown to many who have neither the means nor the inclination to judge.

Featured image: Brigade Road in Bangalore. Photo by Ryan. CC BY 2.0 via ryanready Flickr.

The post Three Cuts appeared first on OUPblog.

Music and what it means to be human

Music is a human construct. While sound may exist as an objective reality, for that sound to be defined as music requires human beings to acknowledge it as such. What is acknowledged as ‘music’ varies between cultures, groups, and individuals. The Igbo of Nigeria have no specific term for music: the term nkwa denotes ‘singing, playing instruments and dancing.’ A definition in Oxford Dictionaries is ‘vocal or instrumental sounds (or both) combined in such a way as to produce beauty of form, harmony, and expression of emotion.’ To define music in these terms depends on subjective judgements of what constitutes beauty of form and expression of emotion, which of course vary from individual to individual. Indeed, some may argue that what constitutes ‘music’ for them is neither beautiful nor expressive of emotion. Their definition of ‘music’ may be based on different criteria. The proliferation of musical genres in western cultures in recent years, and group identification with them, has led to challenges and questions about what really constitutes music.

Music is universal and found in all cultures. Some have suggested that it is at the very essence of humanity, like language, distinguishing us from other species. Some have argued that music exemplifies many of the classic criteria for a complex human evolutionary adaptation, with evidence for the existence of music tens of thousands of years ago. The earliest musical instrument so far discovered, a bone flute, is estimated to be about 50,000 years old. Even this may have been predated by singing. Music may have a role in relation to mate selection, social cohesion, group effort, perceptual and motor skill development, conflict reduction, safe time passing, and trans-generational communication. However, not all authors agree that music has an evolutionary purpose. Some suggest that music, along with the other arts, has no evolutionary significance and no practical function.

Prehistoric music: Aurignacian flute made from an animal bone, Geissenklösterle (Swabia); José-Manuel Benito Álvarez, CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Prehistoric music: Aurignacian flute made from an animal bone, Geissenklösterle (Swabia); José-Manuel Benito Álvarez, CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia CommonsIn societies today, music has a multiplicity of functions which operate at several levels, from the individual, through to the social group, and society in general. At the individual level music can be a vehicle for emotional expression. Ideas and emotions that might be difficult to convey in ordinary verbal interchanges – love, jealousy, grief – can be expressed through music. Music elicits physical responses, aiding relaxation or stimulating activity, and is particularly effective in changing our moods. Involvement in music provides opportunities for individuals to experience aesthetic enjoyment and be entertained.

At the group level music can be viewed as a means of communication. Music can serve to provide shared experiences and understandings that help to bind together social groups and shape their identity. Used in work contexts, music can facilitate an appropriate level of stimulation for mental or physical activity. Emotional expression can also be important at the group level, for instance, in protest songs. It provides a means of expressing feelings towards subjects that are taboo or where there are inhibitions regarding the expression of emotions like love, whether that’s romantic love or love of God, country, school or institution.

In society as a whole, music provides a means of symbolic representation for ideas and behaviours – whether the state, patriotism, religion, bravery, heroism, or rebellion. Music also contributes towards the continuity and stability of culture and perhaps most importantly to the integration of society. Songs, for example, can encourage conformity to social norms and play a major part in indicating appropriate behaviour and providing warnings to others. Music may also play a major role in inciting challenges to those social norms and can define groups in conflict. It provides validation of social institutions and religious rituals and plays a major part in all major ceremonial occasions, from weddings and funerals to military functions and the Olympics. In a more sinister turn, we can also see the power of music in attempts by states to exert control over it, from mass rallies in Nazi Germany to the censure of the music of Shostakovich by the Soviet government. During the Cultural Revolution in China, western music was denounced as decadent and forbidden.

And so as psychologists, we must keep these shifting definitions in mind when examining music in the context of the origins and functions of music; music perception, responses to music; music and the brain; musical development; learning musical skills; musical performance; composition and improvisation; the role of music in everyday life; and music therapy.

Featured image: ‘the audience is shaking’. Photo by Martin Fisch. CC BY-SA 2.0 via marfis75 Flickr

The post Music and what it means to be human appeared first on OUPblog.

10 facts you should know about moons

Proving to be both varied and fascinating, moons are far more common than planets in our Solar System. Our own moon has had a profound influence on Earth, not only through tidal effects, but even on the behaviour of some marine animals. But how much do we really know about moons? Watch David Rothery, author of Moons: A Very Short Introduction tell us what he thinks are the top ten things we should know about moons. Do you have a fact about moons you think should be added to the list? Let us know in the comments below!

Our moon is the only moon that doesn’t have its own name.

It’s not just the moon that causes tides in the Earth’s oceans.

Pieces of the moon sometimes fall to earth.

Contrary to belief, there is no dark side of the moon.

It was the discovery of the moons of Jupiter that first demonstrated that not all motion in the universe goes around the Earth.

It’s not just planets that can have moons.

Most moons orbit in the same direction that their planet is spinning.

Jupiter’s moon Io is the most volcanically active body in the solar system.

Some moons are so cold; the ice on the surface behaves just like rock.

Moons such as Jupiter’s Europa are some of the more likely places where alien life could be found.

Featured image credit: ‘Full Moon’, by Mhy. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post 10 facts you should know about moons appeared first on OUPblog.

March 24, 2016

A Trollopian reviews the Doctor Thorne TV adaptation

Like all true Trollopians I carry in my mind a vivid picture of Barsetshire and its people. For me it is a landscape of rolling countryside with ancient churches and great houses, with Barchester a compact cathedral city of great elegance, as if Peterborough cathedral had been miraculously transported ten miles into Stamford. In Trollope’s novels, the characters are so convincing they seem like people you know. They appear to do what they do because of who they are. Essentially the novels probe the psychological depths, moral dilemmas and inconsistencies of the characters in a way that would not be seen again until well into the 20th century. As P. G. Wodehouse wrote to an American friend from Paris in 1945 on reading Trollope for the first time, ‘it is rather like listening to somebody who is a little long winded telling you a story about real people.’

So how did the TV adaptation of Doctor Thorne stack up? When I first see a favourite novel transferred to screen I am usually struck first by the production and whether I feel transported into the world of the book. The adaptation was unexpected at first: there was the rolling countryside and stunning National Trust houses of course. But the sun was always shining during outdoor scenes and the candles cast an equally warm glow inside. There was also a pace and freshness to the action quite unlike previous small-screen Trollope adaptations which tended to present the Victorian world as stiff and frankly rather colourless. Surely the costumes in Doctor Thorne were too colourful and the ladies’ hairstyles involved too many flowers? Frank and Mary couldn’t have flirted so openly? Or could they? I rapidly became engrossed in this new take on a familiar world. But what about the story? Could Lord Fellowes succeed in turning this bitter-sweet novel of moral choice, alcoholism, money and love into compelling Sunday night TV drama for the post-Downton Abbey viewer? I think it was a success, though I am sure not all Trollopians will agree. Trollope is a personal thing as you may have realised by now.

Trollope begins chapter one of Doctor Thorne with a somewhat dreary description of Barsetshire, the houses and the characters. Fellowes began episode one with a gritty scene of Barchester some 20 years before the main action of the story begins. We learn from the outset the events that drive the plot. Scatcherd – enraged that his unwed sister had been impregnated by Dr Thorne’s dissolute brother Henry – murders him in a fit of anger. The sister emigrates leaving Dr Thorne to bring up the child Mary as his own. We soon learn that Mary’s mysterious parentage and lack of a dowry could limit her options in the marriage market, especially when her suitor Frank Gresham ‘must marry money’ because the entailed family estate is on its last legs and mortgaged to Scatcherd – who is by now – an ennobled and seriously wealthy construction magnate.

Frankly, it doesn’t take us long to work out Mary will inherit Scatcherd’s wealth and so be able to marry Frank and save his estate, but Fellowes’s screenplay kept me entertained to the end, for the most part because of the well-crafted writing of the supporting scenes and of course, the fine cast. The election episode is a standard in many Trollope novels (the author himself stood unsuccessfully for a seat in Beverley) and Fellowes couldn’t resist giving this a lively treatment complete with a rowdy hustings scene featuring rustic ‘downstairs’ folk and their livestock alongside the wealthy candidates Moffat and Scatcherd.

Ian McShane as Sir Roger Scatcherd and Tom Hollander as Dr Thorne. Image courtesy of Hatrick Productions and ITV.

Ian McShane as Sir Roger Scatcherd and Tom Hollander as Dr Thorne. Image courtesy of Hatrick Productions and ITV.Fellowes seemed to make ample use of Trollope’s own words, giving a lively recreation of many of the book’s amusing passages. Lady Arabella Gresham’s frustration with her husband’s financial mismanagement, and her desire for her son Frank to ‘marry money’ were well portrayed, as were her scheming encounters with her better off and supremely snobbish sister Lady De Courcy.

Other amusing scenes come from the flirtatious yet chaste friendship between Frank and Miss Dunstable. Strangely this thirty-something patent medicine heiress became American in the TV adaptation, perhaps as homage to Lady Cora of Downton Abbey fame? Trollope did, after all, introduce several American women characters into some of his novels, usually to provide commentary on ‘Englishness’ or as economically desirable marriage prospects.

Fellowes took few liberties with the plot. For the most part scenes mirrored the novel with just a smattering of additional explanations to make the plot flow. Sneakily, though, he couldn’t resist hinting to the viewers that Dr Thorne himself would find love, and with none other than the wealthy Miss Dunstable, something that readers won’t discover until the later novel Framley Parsonage!

Featured image: Stefanie Martini as Mary Thorne, Tom Hollander as Dr. Thorne, Harry Richardson as Frank Gresham and Rebecca Front as Lady Arabella Gresham. Image courtesy of Hatrick Productions and ITV.

The post A Trollopian reviews the Doctor Thorne TV adaptation appeared first on OUPblog.

Is name studies a discipline in its own right?

Name studies have been around for a long time. In Ancient Greece, philosophers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle saw names as central to the understanding of language, providing key insights into human communication and thought. Still, to the present day, questions such as ‘Are names nouns?’ and ‘Do names have meaning?’ are still hotly debated by scholars within both linguistics and name studies, often in connection with the related question ‘How are names used?’ This is not an issue of theoretical interest alone, but one with important implications for neuroscience. Psychologists have long been aware that names are more difficult to recall than words. A better understanding of their linguistic properties should help to explain why they are processed differently in the brain, which in turn will contribute towards the treatment of brain disorders.

In the meantime, different approaches to the study of names have also been developed. For much of the twentieth century, the field was dominated by the question ‘Where do names come from?’ Particularly influential was the English Place-Name Survey, founded in the 1920s by historians and philologists whose primary interests were in evidence for settlement patterns and language history in the Dark Ages. By tracing the origins of the names of ancient settlements and major landscape features, they were able to throw light on population movement during the migration period, settlement patterns during the Early Middle Ages, and lost or partly lost languages. In course of the work, it became apparent that the names of subsequent settlements and smaller landscape features held similar potential for later periods, so the remit of this and other national place-name surveys was gradually extended through the Later Middle Ages to the Early Modern era and beyond.

Image credit: No Name Road by NatalieMaynor CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: No Name Road by NatalieMaynor CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.The names of people also originate in different languages and time periods, but whereas surnames, like place-names, are usually descriptive, personal names in most parts of the Western world are not. Here, then, the major questions are ‘Why are names chosen?’ and ‘How do names reflect society?’ Since personal names are bestowed afresh on each generation, there is more scope for deliberate choice, so the personal name stock can function as an index of changing values on a societal level. So too do the names of commercial products, one of the various types of names to be regulated by law. In a move away from an exclusive focus on etymology, similar questions are now being asked of place-names. Language varieties within the namescapes of multi-lingual urban environments are used to explore community identity, while the Glasgow-based Cognitive Toponymy project takes the relationship between descriptive names and human cognition as a starting-point to investigate how people conceptualize place in Western Europe.

These various approaches are based partly on the analysis of individual names, and partly on the comparison of large groups of names, from which significant patterns emerge. Name studies have thus been transformed by the technological advances that allow huge datasets to be rapidly and efficiently interrogated. Nowhere is this demonstrated more compellingly than in the study of names in literature. Once characterised by fragmented analyses of selected names from individual texts, this field has now been placed on a much more rigorous footing, with an expectation that each name will be considered against the backdrop of the wider corpus of names within the work or even genre to which it belongs. The question is no longer ‘How should this name be interpreted?’ but ‘How should this name be interpreted in its literary and onomastic context?’

It should be clear by now that there are many branches of name studies, including name theory, place-name studies, personal name studies, names in literature, and names in society, and that the field itself is interdisciplinary, relating closely to such disciplines as archaeology, geography, history, linguistics, literature, philology, philosophy, psychology and social science. One question remains. Is name studies a discipline in its own right? A growing number of universities in various countries offer courses on name studies, but I know of no degree programme on the topic. It is possible to study names as part of a degree, but not to be awarded a degree in name studies. Is it time for that to change?

Featured image credit: Enough with the names already by James Cridland. CC-BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers