Oxford University Press's Blog, page 515

April 30, 2016

Nelson Rockefeller enters presidential race

On 30 April 1968 Nelson Rockefeller, the moderate Republican governor of New York, stepped before a podium in the state capitol of Albany and announced that he was throwing his hat in the ring for the Republican presidential nomination.

Rockefeller said he was disturbed by the “dramatic and unprecedented events of the past weeks,” namely the assassination of Martin Luther King on 4 April and the subsequent riots that rocked dozens of American cities.

The announcement, however, came a mere six weeks after Rockefeller had announced in midtown Manhattan, after a “realistic appraisal” of his standing within the Republican Party, that he would not be running for president in 1968.

In retrospect, Rockefeller’s vacillation should not have elicited much shock. After all, announcing whether he would or would not be running for president had become a quadrennial rite of passage — one accompanied by an uncanny ability to choose the wrong moment either to take the presidential plunge or stay on the sidelines.

Rockefeller’s back-and-forth in 1968 was the product, however, of a deeper and more enduring political obstacle. More than just some garden-variety, “me-too” moderate Republican— Rockefeller was a true believer. A technocrat and a reformer, he brimmed with ideas for how to use the power of the public purse to alleviate hardship and create opportunity. As governor of New York, he had transformed the state, investing billions in new government-led projects and initiatives. Nelson Rockefeller was a doer. Unfortunately for him, he sought to lead a political party ideologically opposed to doing.

Rockefeller’s role as the standard bearer of the moderate wing of the GOP was not supposed to have occurred in 1968. He had twice tried previously to win the Republican nomination. In 1960, he had first announced he was not running and then later changed his mind. His last minute agreement with the eventual nominee Richard Nixon to modify the party platform sparked howls of outrage from conservatives. Four years his ill-fated effort would be capped off by a tumultuous appearance at the Republican National Convention in which he was booed by supporters of Barry Goldwater for taking aim at rising extremism within the party.

By 1968 it seemed Rocky’s time had come and gone. Instead, Michigan Governor George Romney would take up the moderate mantle. Though his disastrous ’68 campaign is best remembered for his comment that he’d been brainwashed into initially supporting the war in Vietnam, in reality, Romney’s biggest problem was that like Rockefeller he was too liberal for the GOP’s increasing conservatism.

Only weeks before the New Hampshire primary – and with his poll numbers showing a likely catastrophic defeat – Romney threw in the towel. Most observers expected Rockefeller to jump in, but neither he nor his staff could figure out a way to make it work. Not only did he lack strong grassroots support and expected to get trounced in presidential primaries, many Republican leaders wanted him to run simply because they expected him to lose and thus give Nixon a boost on his way to the nomination.

For Rockefeller, who like most politicians of that era, loathed Nixon, that was a bridge too far.

Weeks later, with Johnson out of the race and Robert Kennedy looking to many like the possible Democratic nominee (and a more attractive national candidate) Rockefeller believed the political situation had moved in his favor. Eschewing the state primaries, Rockefeller would make his pitch directly to GOP convention delegates, namely that he was the candidate best able to help the party take back the White House.

Rockefeller’s entire campaign, in fact, would be predicated on his weak standing inside the party. An internal campaign memo from late May 1968 described Rockefeller’s dilemma in vivid detail: “While the current campaign obviously involves the Republican nomination and not a general election, the essential target of public policy is strength in the polls—and not the presumed preconceptions of GOP delegates.”

His spring campaign accentuated issues with more national than conservative appeal. He talked about “restructuring” and “streamlining” the “federal establishment” so that “the government is able to deliver on its major policy objective.” He called for a massive new federal commitment of $150 billion over ten years in new spending for America’s cities—$100 billion of which would come from an “aroused citizenry and a proud government.”

And he refused to back down from his long-standing pro-civil rights record. “This would insult not only my integrity, but your intelligence,” said Rockefeller at a speech in Atlanta.

Rockefeller’s move leftward became even more pronounced after Kennedy’s assassination. “I think the people who supported Bobby Kennedy are going to come to me now,” he confidently told his staff. Rockefeller’s speechwriter Joseph Persico would archly note, “No Kennedy supporters were going to be delegates to the Republican convention.”

Behind the scenes, Rockefeller tried to neutralize conservative opposition to his candidacy. A trip to South Carolina to woo the state’s convention delegates produced mixed results. GOP state chairman Harry Dent reported that those present realized Rockefeller was “without horns or a forked tail” but they also found that, “as far as the Democratic choice goes . . . he was the preferable choice.”

In fact, polls showed at the same time that Rockefeller was improving his standing among Democrats and independents; he was losing it among Republicans. “The closer he comes to demonstrating that he might be the one Republican to win in November,” wrote pollster Louis Harris, “the weaker he becomes in his own party.” That July in Miami Beach at the Republican National Convention, Rockefeller would lose to Nixon. But he’d also watch the ideological direction of the party move even more dramatically to the right, as the greatest threat to Nixon came not from the left but from the political right, in the short-lived campaign of California governor and conservative darling, Ronald Reagan.

Indeed, for GOP moderates, 1968 would represent a crucial turning point. Though they continued to play a leading role in the party for the next two decades, only with rare exception would the language of Republican liberalism, as championed by politicians like Rockefeller, feature prominently in the party’s presidential nomination battles.

In the years to come the Republican Party would be dominated by a new version of “me-too-ism”— namely, persistent competition among presidential hopefuls to move further and further toward the right. The trajectory of Republican politics that became more conservative in 1968 would gather speed in the years afterward—so much so that today moderate Republicanism is something read about in history books, not practiced by actual politicians.

Feature Image:White House Mansion by skeeze. Public Domain via Pixabay

The post Nelson Rockefeller enters presidential race appeared first on OUPblog.

Is word-of-mouth more powerful in China?

The sheer size and increasing wealth of the Chinese population makes China an attractive target market. There is no doubt that Chinese culture and history differs from the western world, but how do these differences translate into differences in Chinese buyer behaviour? And are there differences that should affect a brand’s growth strategy?

Given the importance of family, relationships, and social networks in the lives of the Chinese people, there is frequent speculation that WOM will have more influence on Chinese buyers. This can lead marketers to invest in more WOM-generation activities in China, at the expense of mass advertising. Two factors determine the usefulness of any media: reach and impact. WOM has limited reach, but might have more impact on those reached. We tackle the assumption that Chinese buyers are more affected by WOM than buyers in the United States.

Professor Robert East highlights that to determine the relative influence of any received brand advice, you need to know the starting point, i.e. how likely they were to buy the brand prior to receiving the WOM. Buyers vary in their brand purchase propensities—some get WOM about a brand they are already highly likely to buy, while others get WOM about a brand where they have little initial interest.

East and colleagues found WOM is more influential when it reaches people with less chance of buying the brand initially, and is less influential on those with a higher probability of buying a brand. This is important when researching WOM in China, and comparing results to other countries.

For example, when we compared the influence of WOM in the automobile market in China versus the United States we found that China has a less mature automobile market. This means more buyers have a lower benchmark probability of buying a brand of automobile before they receive any WOM, compared to a similar sample of car owners from the United States. Figure 1 illustrates that the majority of category buyers from China have a benchmark probability of 40–60%, and three times as many people from the United States have a benchmark probability of over 90%. These differences affect aggregate assessments of impact.

Figure 1: Benchmark probability of buying a car brand prior to receiving WOM. (Adapted from figures in Chapter 7: Word-of-Mouth Facts Worth Talking About, How Brands Grow: Part 2)

Figure 1: Benchmark probability of buying a car brand prior to receiving WOM. (Adapted from figures in Chapter 7: Word-of-Mouth Facts Worth Talking About, How Brands Grow: Part 2)One way to see if WOM really has a greater influence on Chinese buyers, compared to those in the United States, is to look at people who have a similar benchmark probability in the same category. So we compared buyers in each country with a benchmark probability of 50% chance of buying the brand. The result showed no evidence that WOM is more influential on the Chinese. So it would be misguided to invest a lot in WOM generation activities in China thinking that it would have a substantially higher impact. It might be that WOM has greater reach, or cut through, and these are possible reasons for investing in WOM (they of course need similar testing), but we don’t see any evidence of WOM’s higher impact.

So what of other established knowledge about China, such as loyalty, brand competition, brand associations, attitudes and cross media exposure. Our evidence is that much of the empirical knowledge from western markets also holds in China. When it comes to the laws of growth, China is a different country, not a different planet!

This doesn’t mean that important differences between China and western markets don’t exist. It’s just that we need to be careful to disentangle real differences in buyers from transient differences in factors such as category experience/maturity. Otherwise, you risk being caught out when the market does mature, as is happening in many packaged goods categories in China.

On a final note, just because the strategic path to growth might be similar in China, it doesn’t mean marketers can just roll out a ‘one size fits all’ marketing plan. China does have some major differences that will influence tactical choices, as do India, Indonesia, Brazil, and other emerging markets. Whether your global brand is just getting started or is well established and looking to fight off competitors, prioritise smartly and avoid the common pitfalls of assuming there are big differences rather than relying on the evidence.

A version of this article originally appeared on the OUPblog.

Featured image: Beijing Front Gate. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Is word-of-mouth more powerful in China? appeared first on OUPblog.

A dozen ways to die in Shakespeare’s tragedies [infographic]

In early modern England, social violence and recurring diseases ensured death was a constant presence, so it is only natural to find such a prominent theme in Shakespeare’s plays, especially his tragedies. His characters died at the hands of one another more often than from natural causes, whether stabbing, poisoning, or beheading (or a combination of the three!). But physical brutality is not only source of pain — which is worse: to die of shame, shock, or grief? And so in death, Shakespeare can explore the fragility of human nature and the precarious nature of our mortality.

Infographic courtesy of Caitlin Griffin and the National Theatre Bookshop. Used with permission.

Featured Image: “Ophelia” by John Everett Millais. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post A dozen ways to die in Shakespeare’s tragedies [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know Immanuel Kant? [quiz]

This April, the OUP Philosophy team honors Immanuel Kant (April 22, 1724 – February 12, 1804) as their Philosopher of the Month. A teacher and professor of logic and metaphysics, this Enlightenment philosopher is today considered one of the most significant thinkers of all time. His influence is so great, European philosophy is generally divided into pre-Kantian and post-Kantian schools of thought.

But how much do you really know about this philosopher? Test your knowledge of Kant with our quiz below.

Quiz image credit: Portrait of Immanuel Kant. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: Kant, portrait. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How well do you know Immanuel Kant? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

April 29, 2016

Queer history happens everywhere

With the summer issue of the Oral History Review just around the corner, we are bringing you a sneak peak of what’s to come. Issue 43.1 is our LGBTQ special issue, featuring oral history projects and stories from around the country. To dig more into the issue, we sat down with Scott Seyforth and Nichole Barnes to talk about their article, “‘In People’s Faces for Lesbian and Gay Rights’: Stories of Activism in Madison, Wisconsin, 1970 to 1990.” Drawing from the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s LGBTQ oral history archive, their article offers a rethinking of the common stories we tell about the trajectory of LGBTQ rights and activism, showcasing the important role of university towns and the Midwest in shaping queer history.

The archive contains over 200 hours of oral history interviews. In sitting down to actually write the article, how did you decide where to start?

Well, one thing that we really wanted to address is that a lot of the history of queer liberation hasn’t been told, especially in the Midwest. The queer liberation mass-movement happens everywhere, not just on the coasts. But from reading the history books, you’d think queer Midwesterners weren’t doing much. The article addresses some of these gaps, showing how queer politics evolved in Madison, from very early in the days of queer liberation. Drawing on the interviews we have done with many of the participants in this history, we’re able to let them speak back to history and highlight their accomplishments.

Another big thing we really wanted to do with the article was to highlight the varied holdings of the university that go so far beyond just institutional records. Many people would never expect the university archives to have such a broad collecting scope so we wanted to let people know that there’s more here for those who want to come and explore it. Really, in the article, you’re just getting a glimpse of what the archive has collected so far.

A big part of that problem goes straight back to the way that queer history is remembered. You would assume that New York or San Francisco would have great queer collections – and they certainly do – but there’s history here in the Midwest. Queer culture doesn’t come solely out of the coastal cities, but also from places like Madison, where people are making really interesting change in their communities. During the same time period as this article, the early 1970s, other Midwestern cities with university populations are producing really interesting change. Places like Champaign/Urbana, Ann Arbor, and the West Bank of the University of Minnesota await study, to name just a few.

Madison Lesbians marching in the International Women’s Day March in Madison, WI, March 1973

Madison Lesbians marching in the International Women’s Day March in Madison, WI, March 1973Having been active in the project for years, could you talk about some of the challenges you’ve come across, either in conducting the interviews or in writing up the article.

Some of the very first people interviewed for the oral history project were people who were politically involved. They were some of the most “out” and the most public. They didn’t mind telling their story; in fact they had been doing so for decades. They were also the most well-documented, in newspapers and other sources at the time. So, when we went to write the article, the history of local political involvement was one we could tell in a conventional manner using oral histories and traditional documentation. On the one hand, we are telling an unexamined history—and on the other hand, we are replicating the common problem of telling the history of the most privileged. The project is still collecting materials that will allow future researchers to illuminate diverse aspects of the local community, uncover hidden truths, and engage broadly in telling local stories.

Working on the article has offered an intimate portrait of the way history is constructed. Memories are so malleable, and getting to hear as the past is recreated in an interview has been incredibly instructive.

Many LGBTQ people grow up thinking they don’t matter, and their stories should be kept hidden, so I imagine this is a problem faced by other people doing similar projects. How have you been able to get people to participate?

“LGBTQ individuals oftentimes internalize society’s silencing of history. It can be validating to have someone come and interview you about your life, your activism, and your efforts toward equality.”

For so many of the people interviewed, just having somebody sit and listen for an hour or two is an absolute gift. LGBTQ individuals oftentimes internalize society’s silencing of history. It can be validating to have someone come and interview you about your life, your activism, and your efforts toward equality. At times, narrators weren’t prepared for the way that doing something seemingly so simple as an interview would interrupt the secrecy, denial, and omission of LGBTQ history for individuals.

It’s amazing how willing people are to share once you just offer them a space to talk. In the best oral histories, the interviewer fades quickly into the background, offering a really light touch when needed, but mostly just letting the interviewee share their life.

This might be a good place to pull back and talk about the future of the project, which you allude to in the article. How did the oral history project develop into the Madison LGBTQ Archive?

You know, the oral history project had this problem where we would interview somebody and at the end they would say, “Hey, I’ve got all this great stuff here! Why don’t you take it too?” And, of course, we absolutely wanted to hold onto it, but we simply didn’t know where to put it. We were talking earlier about how little LGBTQ history gets preserved, and here we were, early in the oral history project, seeing this problem in action. After a number of years racking our brains and asking around to different local archives and agencies to see who could house the materials, we finally decided it might make sense to start it at the university archives and have it be connected to the oral history project.

The oral history project has been really instrumental in establishing the LGBTQ archive. Many of our first collections came directly from the people we had interviewed. We could finally go back and say, “Remember that stuff you wanted to give us? Bring it over!” Additionally, the work we had done with the oral history project helped to secure funding, since we could point to those as proof that we were serious and that the funds wouldn’t be squandered. Having already built some relationships with members of the community, we were able to hit the ground running. We continue to try and build community involvement in the project, from the funding to the outreach, to the people involved in putting it all together. I guess we shouldn’t be surprised at how receptive many members of the community have been towards the project. People are excited to finally have a chance to tell their stories in this way.

The post Queer history happens everywhere appeared first on OUPblog.

Happiness can break your heart too

You may have heard of people suffering from a broken heart, but Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) or “Broken heart syndrome” is a very real condition. However, new research shows that happiness can break your heart too. TTS is characterised by a sudden temporary weakening of the heart muscles that cause the left ventricle of the heart to balloon out at the bottom while the neck remains narrow, creating a shape resembling a Japanese octopus trap, from which it gets its name.

Since this relatively rare condition was first described in 1990, evidence has suggested that it is typically triggered by episodes of severe emotional distress, such as grief, anger, or fear. Symptoms of Takotsubo syndrome can mimic those of heart attack. In both conditions, people can experience sudden onset of chest pain and/or shortness of breath. Laboratory findings such as troponin (a protein released from heart muscle cells) can be elevated in both conditions as well. Additionally, ECG characteristics, which provide more details on electrical pathways in the heart, can also be very similar between TTS and heart attack patients. Therefore, telling the conditions apart is very challenging. Much more than just an expression, this is a serious condition which can lead to rapid heart failure and even death. Unlike heart attacks, where angiography (a catheter is used to assess patency of coronary arteries) will reveal blocked arteries, TTS patients have normal blood flow in their coronary arteries. Therefore, stents (metallic devices to keep the artery open) are not the mainstay of therapy, unlike patients with heart attack. The treatment for TTS patients is supportive care and majority of patients with this condition will recover their heart function in weeks to months.

To date, there have been no studies linking positive emotional experiences to heart failure of this kind. However, new research suggests that happy events can also trigger the same condition. Systematically analysed data from the International Takotsubo Registry (the largest registry of patients diagnosed with TTS worldwide) found that 485 of the 1,750 registered patients had a definite emotional trigger. The exact mechanism of involved in processing intense emotions and subsequently their effect on heart function is not known. Nonetheless, we postulate the neurohormonal pathways activated in the brain by emotions can play a key role. Of the patients in our study, 20 (4%) had TTS that had followed happy and joyful events such as a birthday party, wedding, surprise farewell celebration, a favourite rugby team winning a game, or the birth of a grandchild; 465 (96%) had occurred after sad and stressful events, such as death of a spouse, child or parent, attending a funeral, an accident, worry about illness, or relationship problems and one occurred after an obese patient got stuck in the bath.

Munich by MoreLight. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Munich by MoreLight. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Interestingly, 95% of the patients were women in both the “broken hearts” and “happy hearts” groups, and the average age of patients was 65 among the “broken hearts” and 71 among the “happy hearts,” confirming that the majority of TTS cases occur in post-menopausal women.

These new findings should lead to a paradigm shift in clinical practice as they show that the triggers for TTS can be more varied than previously thought. A patient suffering from TTS is no longer the classic “broken hearted” patient, and the disease can be triggered by positive emotions too. Clinicians should be aware of this and also consider that patients who arrive in the emergency department with signs of heart attacks, such as chest pain and/or breathlessness, even after a happy event or emotion, could be suffering from TTS just as much as a patient presenting after a negative emotional event. The findings broaden the clinical spectrum of TTS and suggest that happy and sad life events may share similar emotional pathways that can ultimately cause TTS.

Perhaps extremes of the human emotional range, both positive and negative, are more closely related in impacting the cardiovascular system that previously thought. Understanding the pathways between the brain and the heart is not only fascinating as they unravel the pathophysiology of this particular syndrome, but also allows development of unique and innovative therapeutic ways to treat cardiovascular disease.

Featured image: Smile by Giuliamar. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Happiness can break your heart too appeared first on OUPblog.

Family of Innovators: The Rays’ quest for modernity

Virtually everybody has heard of the filmmaker, writer, graphic artist, and composer Satyajit Ray (1921-1992) but except for Bengalis, few know much about the exploits of his formidable ancestors and their kinsfolk. And yet, over years of versatile creative engagements, Upendrakishore Ray (1863-1915), his father-in-law Dwarakanath Ganguli (1844-1898), his brother-in-law Hemendramohan Bose (1864-1916), his son Sukumar (1887-1923), and daughter-in-law Suprabha (the parents of Satyajit) charted new paths in literature, art, religious reform, nationalism, business, advertising, and printing technology. Not simply a chronicle of one family’s extraordinary accomplishments, the history of the Rays and their collateral connections is also a history of some lesser-known facets of Indian modernity.

From Scribes to Professionals: The earliest known members of the Ray family belonged to the scribal classes of Mughal-era Bengal. After the coming of the British, the family made successful transitions into a variety of new roles and professions whilst avoiding white-collar office-work, law and medicine – the favoured option for most of their scribal peers. This unusual approach has been retained well into the present – unlike most Indians of the modern period, hardly any of the Rays have ever held an office job or been a lawyer or doctor.

From Zamindar to Artisan: Not all the transitions negotiated by the Rays were socio-economic. At least one was profoundly personal. One branch of the clan, who were wealthy landowners in Mymensingh in eastern Bengal, adopted Kamadaranjan Ray, the five-year-old son of a kinsman and installed him under the new name of Upendrakishore as the son and heir of the family. Shuttled between two different social identities from childhood, the artistically gifted Upendrakishore never fully embraced either. At odds with the mainstream Hindu faith of his adoptive as well as biological families and not keen on living as a rural landowner or a scribe, he moved to Calcutta, studied science, became an artisan (repairing musical instruments and then establishing himself as a photographer) and writer, converted to Brahmoism, and married Bidhumukhi, the daughter of one of the great Brahmo radicals of the age, Dwarakanath Ganguli.

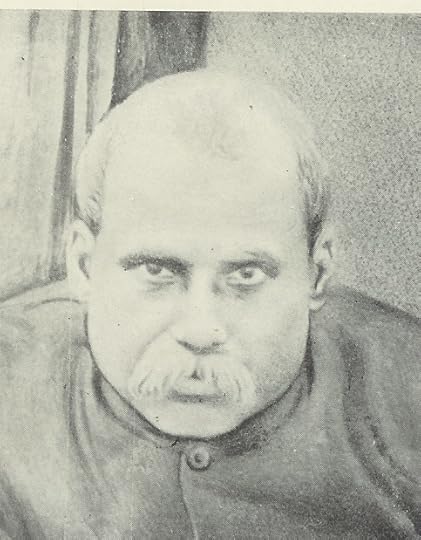

Dwarakanath Ganguli. Bethune School and College Centenary Volume 1949. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Dwarakanath Ganguli. Bethune School and College Centenary Volume 1949. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Brahmoism, Social Reform, and Modernity: A monotheistic variety of Hinduism influenced by Unitarian Christianity, the Brahmo faith never had too many adherents but its social reform initiatives were highly influential. One of the greatest Brahmo reformers was Upendrakishore’s father-in-law Dwarakanath Ganguli. The founder of one of the earliest Bengali journals for and about women, he and his associates established two boarding schools for girls, where Ganguli himself did most of the teaching and which were the very first girls’ schools to prepare their students for university.

The New Woman: One of Ganguli’s students, Kadambini Basu (c.1862-1923), eventually became one of the first two women graduates of Calcutta University, and as if that weren’t enough, went on to enroll in medical school, becoming one of the first women doctors in India. Just before commencing her medical studies, she raised many eyebrows by marrying her mentor Dwarakanath Ganguli, who was nearly twenty years her senior and a widower with two children. It turned out to be a very successful match, proving that the New Woman could excel in both professional and personal life.

Kadambini Basu Ganguli. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Kadambini Basu Ganguli. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The New Nation: Dwarakanath Ganguli’s reformism was not confined to the private, domestic sphere. Along with many of his Brahmo associates, he worked energetically to build up one of the earliest nationalist bodies in British India, the Indian Association. Founded in 1876, it predated the Indian National Congress by some ten years and one of its most striking initiatives was Dwarakanath Ganguli’s investigation of the ill-treatment of tea-garden labourers in Assam. Ganguli’s exposés appalled people across Bengal and India and triggered revisions of colonial labour laws.

The Very Image of the Modern: Whilst working as a photographer, Upendrakishore grew interested in the printing of photographs. The booming print culture of nineteenth-century Bengal could only offer woodcuts and Upendrakishore was the first Indian to master the new half-tone process that captured intermediate tones between black and white and, therefore, enabled a printed picture to retain the tonal variations of the original. Learning this complex craft entirely from books and instruments he procured from England, Upendrakishore soon become the premier blockmaker of Calcutta. Although he was never to step outside India, he also attained a global reputation with articles in the leading British journal on printing technology proposing improvements to the half-tone process. His highly-praised innovations reversed the logic of the colonial marketplace, in which the West was in charge of all innovation and the East merely a grateful purchaser.

Importing, Advertising and Selling the Modern: Upendrakishore was a businessman but it was research and innovation that lay closest to his heart. His brother-in-law Hemendramohan Bose (1864-1916) was very different. A very successful perfumer, Bose’s innovative advertising campaigns for his cosmetic products – especially the literary competition named after his hair oil Kuntaleen, which pioneered product placement in India – deserve a place in any history of modern advertising in South Asia. Bose was also among the first indigenous businessmen to sell phonographs, phonographic recordings (including of Rabindranath Tagore singing his patriotic songs), bicycles, and motor cars to the Calcutta gentry.

Edutainment and the Future Nation: Upendrakishore wrote and illustrated for children from his undergraduate days, contributing prolifically to the new children’s magazines emerging in nineteenth-century Bengal. Brahmos were prominent in this field too, and the project complemented their involvement with women’s education. The overarching aim was to create a true civil society in India, where men and women would participate equally (though not identically) and which would be constantly replenished by young people inculcated with the right values. Perhaps the most famous exemplar of this project was the magazine Sandesh, which Upendrakishore founded in 1913. Initially written and illustrated entirely by Upendrakishore and printed with his own blocks, Sandesh represented the culminating achievement of his career, combining his literary gifts, artistic abilities, technological wizardry, and artisanal insistence on doing everything with his own hands.

After Upendrakishore – New Identities and Old Values: Upendrakishore’s eldest son Sukumar (1887-1923) was a worthy successor to his father. His nonsense writings extended the family’s hegemony over children’s literature and despite being clearly inspired by Carroll and Lear, were Indian and Bengali to the core. Charismatic and gregarious, he was also a leading young activist of the Brahmo Samaj and engaged in many a battle with its elders. His wife Suprabha combined tradition and modernity in a different way. After her husband’s tragically early death and the bankruptcy of the family business, she and her son Satyajit – delivered by the aging Dr Kadambini Ganguli – faced a calamitous situation, from which they were saved by a combination of old values and new identities. The widow and her son, not even three years old at the time, found a home with Suprabha’s brother and the future filmmaker grew up in the kind of large and traditional joint family that unimaginative Bengali modernists considered stifling. His mother, meanwhile, took up a job, which was uncommon even amongst the Brahmo women of the time, taught her son at home (he was sent to school only when he was eight), sculpted (often selling her work for good money), and took charge of the kitchen (her cooking was supposed to be superlative) for her brother’s large household. Meanwhile, her son, although not yet displaying much talent, was silently assimilating the values, priorities, and, inevitably, the limitations of the entire tradition that his mother represented with such consummate skill. Satyajit Ray’s cinematic odyssey would be dazzlingly original but it was also, in many ways, a continuation of his family’s long quest for a modernity that was authentically Indian and confidently global.

Sukumar Ray with his wife Suprabha Ray in a studio (1914). Calcutta State Archive. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Sukumar Ray with his wife Suprabha Ray in a studio (1914). Calcutta State Archive. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: Street Scene, probably Calcutta (1865). Museum of Photographic Arts. Accession Number: 1993.033.008. No known copyright restrictions via Flickr.

The post Family of Innovators: The Rays’ quest for modernity appeared first on OUPblog.

Defining resilience

Consider the following scenario: Two women both lost a son in a war. One returns to work immediately and starts volunteering at an organization helping families of fallen soldiers. The other is unable to leave home, spends most of her days crying and sitting in front of her son’s belongings that were left untouched. Who is more resilient? The answer largely depends on how one defines resilience. Some might argue the first woman is more resilient because she has resumed functioning and maybe even found a deeper purpose in life by giving to others. However, others might argue the second woman is actually more resilient as she is allowing herself to mourn whereas the first woman may be avoiding dealing with her son’s death.

Numerous attempts have been made in defining resilience. The term actually originated from the field of physics and was used to define the ability of metals to absorb energy and return to their normal state after the energy was unloaded. As such, resilience can be viewed as a temporary change from which a person recovers. Thus was born the traditional psychological definition of resilience as the ability to bounce back.

However is this sufficient? What about those individuals who seem to get by in life without much effort—are they considered resilient? Or should resilience be found in the process of coping rather than in the end result? And bounce back from what? Is resilience to stress the same as resilience to trauma? Should resilience be viewed only in the face of adversity?

The bottom line is that resilience is hard to define because it is dynamic and multidimensional. It’s possible for an individual to be resilient in one domain yet not another. Take for example the child who is a quiet, obedient student that gets good grades. By all appearances we might assume that this child is resilient, however knowing that he has no friends or is throwing tantrums at home might change our minds. Thus, it is important to examine resilience within multiple contexts. Culture may influence what is considered resilient. Some cultures place more emphasis on physical rather than emotional symptoms. Some value stoicism over emotional expressiveness. Furthermore, resilience changes depending on developmental stage. A child who was successfully treated for sexual abuse at age six and live normally for several years, might have issues arise in adolescence as he starts dating. To further complicate matters, an individual who appears resilient may still be approaching the stress threshold. Thus, what is true resilience?

Although resilience is a difficult construct to define and measure, the good news is that there are things we can do to enhance it. In the same way that stressful experiences can impair neurobiological systems, the brain has the ability to form new neurons and connections in response to novel experiences. Thus, the more a skill is rehearsed the more the brain will rewire. Psychotherapeutic interventions aim to do this through teaching of skills such as affect expression and regulation, cognitive restructuring, and coping/relaxation strategies. Early intervention is important as the brain is most malleable in childhood. There is the idea of stress inoculation, exposing an individual to some level of stress but not too much or too little. However, experiences of minor stress do not necessarily equip a person to be able to handle greater stress. It seems that it is more about whether a person has the desire to overcome. A specific temperamental factor may not be necessary but a key feature of resilient individuals appears to be cognitive flexibility, the ability to adapt to the situation. It is important to keep in mind that the majority of the population, about two thirds, is resilient. Therefore, preventative interventions become crucial in bolstering developmental assets such as problem-solving, motivation, self-esteem, and social competence. Most important, however, may be empowering individuals to draw on their own innate strengths to become their own agents of change. Resilience is not something you either have or don’t, everyone has the ability to become resilient.

Featured image credit: Neuron. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Defining resilience appeared first on OUPblog.

Sikhs and mistaken identity

American basketball star, Darsh Singh, a turbaned, bearded Sikh, featured this April in a Guardian Weekend piece on cyberbullying. He recalled how his online picture had been circulated with Islamophobic captions. Long before that, he’d had to get used to people yelling ‘things like “‘towelhead’, ‘terrorist’, and lots of references to Osama Bin Laden”.

Since 9/11 Sikhs haven’t just been verbally insulted but have suffered ‘reprisal attacks’. Over three hundred attacks were estimated in the USA in the first month alone. Balbir Singh Sodhi, a gas-station owner in Arizona, was killed only four days later. Attackers connect beards and turbans with Islam and terrorism. In 2012 in Wisconsin, a white supremacist killed six people in Oak Creek gurdwara (place of worship) and wounded three others. As I write, a deliberate explosion at a gurdwara in Essen, Germany, during the Vaisakhi festival, is being investigated. This time, however, it is ‘Islamist’ teenagers who have been arrested.

Sikhs commemorate the Vaisakhi festival of 1699 which is regarded as the birthday of the Khalsa. The Khalsa means Sikhs – men and women – who commit themselves to a daily discipline, as their tenth Guru, Guru Gobind Singh, exhorted them to do on that day. Sikh families worldwide celebrate Vaisakhi in April, with larger than usual congregations and impressive street processions. These are headed by the enthroned volume of scripture, attended by five men, usually dressed identically in orange and white. They are the “five beloved ones”, a reminder of the first five men who volunteered their lives for their Guru on Vaisakhi day 1699.

In April each year, very early on Vaisakhi day, candidates continue to be initiated into the Khalsa, into a way of life that involves following rules of conduct and a pattern of daily devotion, and also having on their person five indicators of their commitment (these are known as the ‘Five Ks). One of the Ks, the kesh (hair), involves keeping one’s God-given form intact by not shortening or removing hair from any part of the body. Indeed, not only initiated Khalsa Sikhs, but also many Sikhs who have not made this formal commitment, keep their hair and beard uncut.

For male Sikhs their turban is the crown which – together with their kesh – symbolises their faith, inseparable from their identity. (In Asia the turban had for centuries been a respected head-dress for men.) Many initiated women too, nowadays express the Sikh emphasis on equality by wearing a turban.

Sikhs celebrate their history of distinctiveness from Hindus and Muslims, coupled with their self-sacrificial solidarity with humanity as a whole. They know they have been called to stand out from the crowd and to be “saint-soldiers”, always ready to protect people who are suffering injustice. It is an ironic twist that their intentionally distinctive appearance attracts not only racism, but more specifically, Islamphobia, in an escalation of cases of mistaken identity.

In basketball star Darsh Singh’s case, the #belikeDarsh hashtag reminds us that social media can be a force for good.

Sikh history is full of ironies: the British recruited Sikhs enthusiastically into the British Indian Army, regarding them as a “martial race”. Not only that, they required their Sikh regiment to be initiated, to maintain the five Ks and to wear the turban. In the two world wars, over 80,000 turban-wearing Sikh soldiers were killed in combat and over 109,000 were injured. Then in 1947, when India was partitioned, Sikhs’ homeland, Punjab, was bisected and hundreds of thousands of Sikhs had to leave their homes to flee east of the new border.

By the 1950s many Sikhs (as well as Hindus) were migrating from the Indian state of Punjab to Britain to fill vacancies in factories, foundries and transport services. Far from their turbans being generally welcomed, Sikhs faced prejudice and discrimination and felt obliged to cut their hair, remove their turbans, and shave. When bus companies in Manchester and, later, Wolverhampton refused employment to turban-wearing Sikhs, the first of a succession of high-profile protest campaigns got underway. UK Sikhs won the right, in turn, to wear turbans as bus conductors, as motorcyclists, as pupils in school, on construction sites, and in all places of work. In other countries too Sikhs have struggled, sometimes successfully, for their turbans to be allowed. Canada’s Mounties now include turban-wearing Sikhs.

Sikhs have responded in a characteristically positive way to the post-9/11 “mistaken identity” assaults. In the USA they formed the Sikh Coalition, a voluntary educational organisation which works for human rights and in particular, “a world where Sikhs may freely practice and enjoy their faith while fostering strong relations with their local community wherever they may be”.

In basketball star Darsh Singh’s case, the #belikeDarsh hashtag reminds us that social media can be a force for good. Darsh asks us to “continue to educate yourself on traditions and practices different from your own” and “serve those in need”. “Sikhs believe everyone and everything has the potential to embody Divine love.”

Feature Image: Front view of Gurudwara Bangla Sahib, Delhi, by Ken Wieland. CC BY SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Sikhs and mistaken identity appeared first on OUPblog.

April 28, 2016

A timeline of the dinosaurs [infographic]

Dinosaurs – literally, the ‘terrible lizards‘ – were first recognized by science, and named by Sir Richard Owen (who preferred the translation ‘fearfully great’), in the 1840’s. In the intervening 170 years our knowledge of dinosaurs, including whether they all really died out 65 million years ago, has changed dramatically.

From drilling into the crater which was made by a giant meteorite that killed the dinosaurs, to reconstructing feathered dinosaurs who scientists now believe are directly linked to today’s birds (our very own living dinosaurs), scientists are constantly discovering things we didn’t know about these ‘terrible lizards’ that first started to evolve over 250 million years ago. We’re even realizing some things we thought we knew were wrong – and some things we thought had been disproved were ‘right again‘.

But in order to understand these new things we’re learning, we need to revisit the basics that we might have forgotten. Have you ever been reading an article about recent discoveries, and thought that you needed a refresher on your dinosaur knowledge? What were they, again? When were they alive and how did they evolve over time? What was happening to the earth around them?

Take a crash course on the history of the dinosaurs and find out the answers to all these questions, plus discover what types of dinosaurs were roaming in the three key periods (Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous), with our infographic below.

Download the infographic as a PDF or JPG.

All facts in this blog post were correct at the time of publishing – we can’t predict what scientists will discover next, but we’re excited to find out.

Featured image credit: Tyrannosaurus Rex, by LoneWombatMedia. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post A timeline of the dinosaurs [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers