Oxford University Press's Blog, page 516

April 27, 2016

Etymology gleanings for April 2016

Responses to my plea for suggestions concerning spelling reform were very few. I think we can expect a flood of letters of support and protest only if at least part of the much-hoped-for change reaches the stage of implementation. I received one letter telling me to stop bothering about nonsense and to begin doing something sensible. This I think is good advice, even though in my case it came a bit too late. The problem is that one man’s meat (business) is another man’s poison (nonsense). (Meat here means “food,” as in meat and drink, sweetmeats, and elsewhere.) Our other correspondent may be right that the reform had to be launched a hundred or so years ago and that, given our computerized spelling programs, it has no chance of success. However, the computer is unable to distinguish between its and it’s, use to and used to, principle and principal, and even lead and led, to give the best-known examples. In principle, the reform is less about such small fry than about a major effort to make English spelling “user-friendly” (sorry for the cliché). The Society should, in my opinion, go on with the congress, make it as efficient and inexpensive as possible, give up the idea of a huge crowd of participants, solicit the endorsement of a few famous journalists and politicians, and put forward a reasonable (that is, non-radical and attractive) proposal, stressing the benefits of the change for both native learners and millions of foreigners who use English as their main language in communicating with the outside world.

Postscript on “breast”

However close in out intuition breast and burst may be, the words are not related. Time and again experience with “things” changes the meaning and usage of “words” (the quotes refer to the fruitful line of research, known as “Words and Things,” from German “Wörter und Sachen”). Now, a note on the grammatical form of the Germanic word for “breast.” This discussion has the risk of becoming too technical, so that I’ll say as little as possible about the details. An old noun (not only in Germanic but everywhere in Indo-European) usually consisted of three parts: the root, the so-called theme (a vowel or a consonant following the root), and the ending. The theme determined the type of declension. That is why the grammars of Old English, Old Saxon, Old Norse, and so forth speak about the a-declension, the i-declension, the r-declension, and the like. If the theme was a consonant, grammars use the term consonantal declension. With relatively few exceptions, this classification makes little sense to a student of Germanic, because by the time our earliest texts were recorded themes had either disappeared or turned into endings. Only Gothic, saved for us by Bishop Wulfila’s fourth-century translation of the Bible, retained a semi-obliterated system of those themes.

The nominative of the word for “breast” was, apparently, brusts in Gothic. This noun occurred only once in the feminine plural, but the ending shows that it belonged to the same consonantal declension as, for example, baurgs “town,” whose forms have been attested very well (in the singular (nominative, genitive, dative, accusative): baurgs, baurgs, baurg, baurg; in the plural: baurgs, baurge, baurgim, baurgs; naturally, the vocative “o town!” did not turn up, because no one apostrophized any town in the New Testament). No doubt, the reconstructed forms given on the Internet and cited by our correspondent were inspired by the Gothic paradigm.

The reconstructed type of the Germanic declension and my statement that Old Engl. brēost and Gothic-German brust(s) have the vowel on different grades of ablaut are fully compatible, that is, they neither contradict nor depend on each other. Ablaut refers to the regular alternation of vowels, as in Engl. bind—bound, take—took, or choose—chose. Those alternations resembled railway tracks: in most cases, vowels were allowed to move only along such prescribed tracks (exceptions seem to exist and are always hard to account for). One such route, to cite Old English, was ēo—ēa—u—o (typically represented by verbs like choose, from cēosan). One can see that ēo and u belonged together. Consequently, the coexistence of brēost in one language and brust in another, being reflexes of the same root, need not cause surprise.

Parallel tracks. This is how ablaut works.

Parallel tracks. This is how ablaut works.More than ten years ago, the first editor of this blog told me that I did not have to be ruthlessly “popular” and could, if necessary, wade through the more intricate aspects of etymology. However, I try to avoid even such mild asides as would bore most of our readers to death. By way of excuse, I may say that the speakers of Old Germanic (at least of Old Norse) considered the breast the abode of the mind, so that I hope I’ll be forgiven for this rare digression. Besides, my comment was inspired by a question, and questions exist to be answered.

Blunt “money”

The question, in connection with my old post on blunt, was whether I know the obsolete slang word blunt “money” and, if I do, what is its origin? Yes I know the word and am aware of three suggestions about its etymology, those mentioned in Farmer and Henley’s Slang and its Analogues.

From blond “sandy or golden color”;

in allusion to the blunt rim of coins; and

from Mr. John Blunt, Chairman of the South Sea Company.

The Internet gives enough information about the South Sea Bubble, which spares me the necessity of going into detail. Quite possibly, all three etymologies are wrong, but, if one has to choose among them, the third looks more realistic. In my database, there is nothing on this word.

The statement is blunt: beware of blunt.

The statement is blunt: beware of blunt.In praise of antedating: slowcoaches and their passengers

In 1890, while working on the letter C, James A. H. Murray sent out one of his letters asking for earlier and later examples of very many words. It is instructive to compare some of the dates he had with those now available. This comparison tells us how slow the progress in the game of antedating sometimes is. For instance, coach “carriage” moved from 1561 only to 1556 and coach “tutor” from 1854 to 1849 or rather 1850. Coarse (said about language), coastguard, and coax remained frozen at 1633, 1833, and 1589 respectively. By contrast, (carry, send) coals to Newcastle is now dated to 1614, while Murray had 1813. Murray’s earliest citation for coat of arms had the date 1601. Now we know that Caxton used this phrase in 1490, but (amazingly!) there is not a single occurrence of it between 1490 and 1601. Sometimes an earlier date allows us to modify the old views on the word’s origin (Murray succeeded in rejecting numerous conjectures that were, to use his phrase, at odds with chronology). Quite as often antedating gives the researcher an insight into the history of a cultural phenomenon (for instance, coalition as a political term surfaced not in 1642 but already in 16O5), and occasionally all we obtain is a fact of minor importance (take coach: whether it made its way into print in 1556 or 1561 is almost irrelevant). But one cannot expect a revolution at every step. The game is worth more than a candle.

A coach: it makes haste slowly; so does the procedure of antedating.

A coach: it makes haste slowly; so does the procedure of antedating.Image credits: (1) Railway tracks. CC0 via Pixabay. (2) Tree caricature from South Sea Bubble cards, 1720. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Carriage Drawn by a Horse by Vincent Van Gogh. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Etymology gleanings for April 2016 appeared first on OUPblog.

Bioinformatics: Breaking the bottleneck for cancer research

In recent years, biological sciences have witnessed a surge in the generation of data. This trend is set to continue, heralding an increased need for bioinformatics research. By 2018, sequencing of patient genomes will likely produce one quintillion bytes of data annually – that is a million times a million times a million bytes of data. Much of this data will derive from studies of patients with cancer. Indeed, already under The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), comprehensive molecular analysis, including exome sequencing and expression profiling, has been performed on more than 10,000 patients.

Given this veritable flood of data, the bottleneck in cancer research is now how to analyse this data to provide insights into cancer biology and inform treatment.

The fruits of cancer bioinformatics research are in fact already making their mark on our understanding of cancer. To date, more than 1,000 studies have been published based on TCGA-collected data alone and these important studies, and others, provide a roadmap for the future of cancer bioinformatics.

Patterns of gene expression, Figure 7 from Integrative Analysis of Response to Tamoxifen Treatment in ER-Positive Breast Cancer Using GWAS Information and Transcription Profiling by Libertas Academica. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

Patterns of gene expression, Figure 7 from Integrative Analysis of Response to Tamoxifen Treatment in ER-Positive Breast Cancer Using GWAS Information and Transcription Profiling by Libertas Academica. CC BY 2.0 via FlickrClinical relevance of the catalogue of drivers and mutational processes

A first step to understanding the mechanisms of tumour emergence, evolution, and drug resistance is to understand the driver events and mutational processes in cancer. Sequencing data has seen an explosion in tools to perform such analysis, shedding light on novel driver events, and the mutational process occurring during tumour evolution. However, these studies have also revealed that neither the catalogue of drivers nor our understanding of the processes that mould cancer genomes is close to complete. Moreover, in general, most studies have only focused on the coding part of the genome.

From a clinical perspective, a key question relates to the clinical relevance of these events and how they can guide clinical decision-making. A recent large-scale computational analysis found that although less than six percent of tumours are tractable by approved agents following clinical guidelines, up to 40.2% could benefit from different repurposing options, and over 70% could benefit when considering treatments currently under clinical investigation. As has been previously discussed, the scale of evidence for genomic events to guide precision medicine needs to be further established.

Cancer genome evolution

To fully understand cancer, we need not only to understand the events, but also when they occur during tumour evolution and how they may facilitate cancer drug resistance. Recent years have seen the development of a plethora of bioinformatics tools to dissect cancer genome evolution and intra-tumour heterogeneity, and these have been used to shed light on the complex clonal architecture of tumours, revealing clonal driver events present in the founding cancer cell, as well as later mutations in cancer genes present only in a subset of cancer cells. These studies highlight the need not only to consider whether a mutation is present or absent, but whether it is present in all or only a subset of tumour cells, which may have major implications for targeted there therapies.

A crucial next step will be to attempt to write the rulebook for cancer genome evolution and how cancer therapy influences tumour evolution.

Cancer immunology

‘Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a T lymphocyte’ by NIAID. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

‘Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a T lymphocyte’ by NIAID. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.One of the exciting breakthroughs in cancer research over the last years has come from work in immunology. The recognition of the importance of tumour-specific neoantigens that may act as targets for immune responses has increased interest in personalized vaccines and strategies to accentuate anti-tumour immune responses, including immune-checkpoint blockade, which seek to unleash a patient’s own T cells to destroy the tumour.

Recent work has begun to reveal the genomic underpinning of when immunotherapy succeeds or fails, and the next steps in extending this work will necessarily require a bioinformatic foundation. In particular, we need to improve the tools to identify neoantigens and also extend our understanding of how the cancer genome shapes and is shaped by anti-tumour immunity.

Taken together, this exciting work provides a platform for future bioinformatics research, both from a methods and an analysis perspective. As the flood of cancer genomic data continues, the need for bioinformatics is more pressing than ever.

Featured image credit: DNA by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Bioinformatics: Breaking the bottleneck for cancer research appeared first on OUPblog.

The Poetic Edda, Game of Thrones, and Ragnarök

Season Six of Game of Thrones is about to air. One of the great pleasures of watching the show is the way in which George R. R. Martin, the author of the A Song of Ice and Fire series, and the show-producers, David Benioff and Dan Weiss, build their imagined world from the real and imagined structures of medieval history and literature. I don’t know whether they have ever read the Poetic Edda, but it’s clear that the series’ conception of the North borrows many themes and motifs from Norse myth.

At the end of Season 4, Bran and his companions had finally located the Three-Eyed Raven, a frightening figure sitting in a dark cave far north of the Wall. His body is twined about with the roots of a tree; through his connection to this tangle he can see all that transpires through the sacred weirwoods of the North. The Raven is one-eyed; this, along with his connection with ravens and crows, and the tree system into which he is incorporated, link him suggestively with Odin.

Just as ravens, with their ‘dark wings’ bring ‘dark words’ throughout Westeros, so Odin gathers knowledge through his two ravens:

“Hugin and Munin fly every day

over the vast-stretching world;

I fear for Hugin that he will not come back,

yet I tremble more for Munin.” Grimnir’s Sayings, v. 20

Like the Three-Eyed Raven, Odin becomes one with the great world-tree Yggdrasill, on which he hangs himself as a sacrifice:

“I know that I hung on a windswept tree

nine long nights,

wounded with a spear, dedicated to Odin,

myself to myself,

on that tree of which no man knows where its roots run.” Sayings of the High One, v. 138

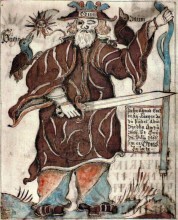

Odin in an eighteenth-century 18th century Icelandic manuscript of the Prose Edda (NKS 1867 4to) via Wikimedia Commons.

Odin in an eighteenth-century 18th century Icelandic manuscript of the Prose Edda (NKS 1867 4to) via Wikimedia Commons.Thus Odin wins knowledge of the past, the present and of the future too. Although he and the other gods will perish at ragnarök (the end of the world), he also knows that his dead son Baldr will return in the new world. ‘All evil will be healed; Baldr will come’, says the Seeress’s Prophecy (v. 59). Does Odin also know of the return of the treacherously slain Jon Snow? I think so.

In Norse myth, wolves are dangerous beasts. So too are the direwolves of the world of Game of Thrones, except with the Stark children to whom they were given as pups; the direwolves become loyal pets. Nevertheless, when, as Theon notes, ‘there’s not been a direwolf sighted south of the Wall in two hundred years’, their appearance is a portent of the many disasters to come.

In the Poetic Edda, two cosmic wolves pursue the sun and moon through the sky, the offspring of the enormous wolf Fenrir who lies chained up until ragnarök. The gods challenged him to see if he could break the slender-looking bonds they brought to him. Smelling deception, Fenrir demanded that someone should place his hand as a pledge in the wolf’s great jaws. The gods hesitated – until Tyr stepped up. As the magic fetter tightened around the wolf’s mighty paws, the gods laughed in triumph. All except Tyr, whose hand was snapped off. Loki, Fenrir’s father, later taunts Tyr with his lack of even-handedness:

“Be silent, Tyr, you could never

deal straight between two people;

your right hand, I must point out,

is the one which Fenrir tore from you.” Loki’s Quarrel, v. 38

Týr and Fenrir (1911) by John Bauer, from Our Fathers’ Godsaga by Viktor Rydberg. Wikimedia Commons

Týr and Fenrir (1911) by John Bauer, from Our Fathers’ Godsaga by Viktor Rydberg. Wikimedia CommonsIt’s easier to function as a one-handed god than a one-handed warrior though, as Jaime Lannister knows to his cost.

At ragnarök, the pursuing wolves will finally catch up with the heavenly bodies; the sun and moon will vanish from the sky:

“In the east sat the old woman in Iron-wood

and gave birth there to Fenrir’s offspring;

one of them in trollish shape

shall be snatcher of the moon.” Seeress’s Prophecy, v. 39

So too, the world in which Game of Thrones is set is heading for apocalypse. The White Walkers are on the march: ‘Cold winds are rising and the dead rise with them’, the Commander of the Night’s Watch reports to the Small Council in King’s Landing. The White Walkers with their powers of regenerating the dead are strongly allied to the forces of winter; their icy touch shatters metal and their faces are rimed with hoar-frost. Norse frost-giants are equally chilly beings: ‘the icicles tinkled when he came in: the old man’s cheek-forest [beard] was frozen’, we’re told in Hymir’s Poem (v. 10).

At the final battle, Loki, in alliance with frost-giants and Surtr the fire-giant, will advance upon Asgard, the home of the gods, and the world will sink beneath into the sea. There are still two seasons – or maybe more – of Game of Thrones to come, so it’s unlikely that ragnarök, the expected showdown between the dragons and the White Walkers, the forces of fire and ice, will occur this year. But the Seeress’s Prophecy gives us a foretaste of what it might be like. And in the meantime there’s all the intriguing ways in which the Poetic Edda’s distinctive world is reimagined in the show. From the Valhalla-like hall of the Iron-Born’s Drowned God, to the warging (shape-shifting) of the Stark children, from Valyrian steel swords to the Free Folk’s spear-wives and shield-maidens, the legendary North is always present.

Featured Image: Game of Thrones – Influencer Outreach Box by C. C. Chapman via Flickr

The post The Poetic Edda, Game of Thrones, and Ragnarök appeared first on OUPblog.

Austerity and the slow recovery of European city-regions

The 2008 global economic crisis has been the most severe recession since the Great Depression. Notwithstanding its dramatic effects, cross-country analyses on its heterogeneous impacts and its potential causes are still scarce. By analysing the geography of the 2008 crisis, policy-relevant lessons can be learned on how cities and regions react to economic shocks in order to design adequate responses.

Focussing on key economic performance indicators for European city-regions in particular, it is possible to explore the links between post-2008 economic performance and pre-crisis factors (including macro-economic conditions) that may have exacerbated (or mitigated) the short-term contraction of the various regional economies.

The figure below depicts the geographies of the crisis across the European Union. The post-2008 regional economic trends show a core continental area, where the impact of the crisis on unemployment have been low or moderately low. This revolves around Germany, most of Poland, and partly stretches to neighbouring regions (such as most regions of Slovakia, and the Czech Republic). This ‘core’ is surrounded by a ring of more peripheral areas where the impact has been high or very high, and which include most of the regions of Ireland, Spain, parts of Italy, Greece, Cyprus, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia.

Average regional unemployment rate during 2004/2007 (left), and average annual variation of unemployment rates during 2008-2012 (right) by Crescenzi, Luca, and Milio 2016 on Eurostat data. Used with permission.

Average regional unemployment rate during 2004/2007 (left), and average annual variation of unemployment rates during 2008-2012 (right) by Crescenzi, Luca, and Milio 2016 on Eurostat data. Used with permission.When these spatially diverse post-crisis trends are linked to the characteristics of the corresponding regions, a significant divide between the regions of the ‘old’ Europe and the new EU member states becomes apparent. In the ‘new’ member states – and in particular in the regions of Poland, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic – the positive post-2008 economic performance seems to be driven by a process of structural and technological catching-up, while still benefiting from the relatively recent integration into the European Union. Such processes seem to be able to ‘balance’ the generalised downturn.

The key question then becomes, how are these regional level dynamics linked to the national macro-economic factors that take centre stage in the debate on the ways to react to crises and ‘shelter’ the EU economy from future shocks?

The link between the post-2008 regional economic performance and pre-crisis national macroeconomic factors highlights the importance of national trade patterns and government expenditure. A healthy current account surplus is associated with a stronger economic performance and better regional employment levels during the post-2008 recession. Conversely, regions belonging to countries with a higher initial government debt did not experience poor economic performance in the short-run, both in terms of economic output and employment. Of course, these are suggestive correlations with no causal interpretation, and they do not necessarily suggest a sustainable long-term pattern. Yet, they provide preliminary evidence on the importance of active government policies before the crisis in mitigating the short-term impacts of subsequent recessionary shocks.

What can regional governments and mayors do to increase the resistance of their cities and regions to global economic shocks?

When examining regional resistance factors, human capital emerged as the single most important regional factor associated with a better resistance to economic shocks. What matters is the capability of the regions to identify short-term innovative solutions to a changing (and more challenging) external environment. This capability does not necessarily derive from technology-driven processes supported by Research & Development (R&D) investments, but is more likely to be boosted by a skilled labour force that enhances rapid processes and organisational innovation. While over the 2000s the European Union has invested conspicuous resources in trying to raise R&D expenditure to 3% of GDP in all countries and regions, an increasing body of evidence has now shown that local R&D investments have a weak association with regional innovation and growth, while human capital is a stronger predictor of that in the long term. Such contrast is magnified when looking at short-term cyclical reactions to the economic crisis; human capital is also key to short-term resistance, while regions with high investments in R&D are not necessarily in the best position to face the crisis. In Europe, it is possible to identify several cases of ‘cathedrals in the desert’ where large (often publicly funded) research infrastructure remain completely disconnected from the needs of the local economic environment.

More academic research is definitely needed in order to answer the many questions raised by this simple discussion of the key facts and figures of the regional consequences of the crisis. In order to identify the regional resistance factors that will be able to positively influence recovery, it will be necessary to wait for more updated data on economic performance, and employ more sophisticated statistical techniques. Research in this area — at the intersection between macro-level dynamics and regional and city-level outcomes — is of paramount importance in order to provide European, national, and regional policy makers with insights on the capabilities of their cities and regions to react to economic shocks and design adequate responses.

A 360-degree public debate on how to re-launch local growth and employment beyond austerity measures is now a priority. The resistance of European cities and regions to economic shocks, and their capacity to find a pattern of sustainable economic growth are premised on a combination of enabling macro-economic environments and balanced regional and urban policies. Whether current EU and national policies (from the macro to the regional level) can provide Europe with adequate answers to these challenges remains to be seen.

Featured image credit: world europe map connections by TheAndrasBarta. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Austerity and the slow recovery of European city-regions appeared first on OUPblog.

April 26, 2016

A prickly pair: Helmut Schmidt and Jimmy Carter

Helmut Schmidt and Jimmy Carter never got on. Theirs was, in fact, one of the most explosive relationships in postwar, transatlantic history and it strained to the limit the bond between West Germany and America. The problems all started before Carter became president, when the German chancellor unwisely chose to meddle in American electoral politics.

Schmidt had developed a close personal rapport with President Gerald Ford (1974-6) and the two of them agreed on many policy issues – building up the G7 summit meetings to stabilize Western capitalism in the face of world economic crisis, and successfully concluding the Helsinki Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe.

The chancellor spoke openly about their relationship to Newsweek in October 1976, three weeks before Americans went to the polls. “I have to abstain from any interference in your campaign,” he stressed, “but I really like your President, and I think he has done quite a bit of help in these past two years. I have been taking advice from him. This has been a two-way affair. But on the other hand, I am not going to say anything about Mr. Carter, neither positive nor negative, I have met him for one hour only”.

The headline “I like Ford” went around the world. Schmidt’s staff were obliged to send apologies to the Carter team, blaming the faux pas on an interview given very early in the morning when the chancellor wasn’t particularly careful about his words. In reality, however, Schmidt’s remarks reflected his true feelings. Speaking to British Prime Minister James Callaghan in May 1976 he had aired his “uncertainty” about how America would cope in superpower relations if “a very much unknown farmer governor” took over the White House.

Unfortunately for Schmidt, he did. And this compounded the diplomatic embarrassment. The new president never forgave Schmidt’s snub — nor did the chancellor change his opinions about the peanut farmer from Georgia.

After this disastrous start, the Schmidt-Carter relationship only went from bad to worse. One might have expected an American Democrat and German Social Democrat to have a similar view of the world but in fact, they clashed on almost every policy issue. Their disagreements were made worse by their temperaments: each being a perfectionist, obsessed with detail, and convinced that he knew best.

In the face of the world economic crisis, Schmidt was irritated by Carter’s obsession in 1977 with economic stimulus packages. The chancellor championed a policy of stability, on the German model (Modell Deutschland), favoring a neo-monetarist approach that promoted sustainable growth and reduced unemployment without fueling already rampant inflation.

On nuclear arms control, Schmidt was appalled that Carter tore up the Ford-Brezhnev agreements at Vladivostok (1974), pressing instead for “deep cuts”. This the Soviets flatly rejected in March 1977, forcing the superpowers to start negotiations again from scratch.

Close up of Jimmy Carter and German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, July 1977. Public domain via The US National Archives.

Close up of Jimmy Carter and German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, July 1977. Public domain via The US National Archives.Friction was exacerbated by Carter’s Baptist passion for an idealist foreign policy, privileging human rights. This was at odds with Schmidt’s focus on realpolitik and the balance of power. Der Spiegel stated bluntly that Schmidt considered Carter “an unpredictable dilettante who tries to convert his private morality into world politics but is in reality incapable of fulfilling the role of leader of the West.” This became evident to the chancellor over what he considered Carter’s flip-flops and eventual cop-out in 1978 on whether to produce and deploy the so-called neutron bomb.

Their personal and policy differences came to a head in an amazing confrontation on the margins of the Venice G7 summit in June 1980. After the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan on Christmas 1979, Schmidt had gone along with Carter’s boycott of the Moscow Olympics but didn’t support economic sanctions against the USSR and wanted to keep open superpower arms control negotiations. He also insisted on sticking to his planned visit to the Kremlin in July. Carter’s anger with what he considered the chancellor’s double-dealing was expressed in a private letter that the White House then leaked to the press.

When the two leaders met in Venice, Schmidt blew his top. Together with their aides they faced off in a cramped, hot, little hotel room – knees almost touching. Carter called it an “unbelievable meeting” with Schmidt “ranting and raving” about the letter and about being treated like “the 51st state”. The chancellor was so incensed that he went over the whole history of their relationship. At one point he even exclaimed “Well, I don’t mind a fight”, to which Carter’s pugnacious national security advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski retorted, “if a fight is necessary I am quite prepared not to shrink from a fight.”

The pyrotechnics helped clear the air a bit. But ultimately the chancellor could never entirely conceal his irritation with the president. American journalist Elizabeth Pond noted shortly after Venice that Schmidt, who “had kept his famous lip buttoned for well over a year on the subject of Jimmy Carter, pointed out that he had been used to thinking for himself and expressing his opinion for thirty years and that he didn’t propose to be instructed now by any newcomer with a lot less political experience.”

The Schmidt-Carter non-relationship was the great aberration from the chancellor’s modus operandi in international politics, which privileged the importance of reliable “political friendships.” His rapport with French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing was the classic example, but his relations with Gerald Ford and Henry Kissinger were equally cordial and productive.

In the end, however, Schmidt and Carter did manage to transcend their personal differences. Both men believed firmly in the transatlantic partnership. And Schmidt had no doubt that Germany’s fate in the Cold War depended on America as its protector power (Schutzmacht). The NATO “dual-track” decision in December 1979 – making an arms control offer to the Soviets under the threat of deploying new Cruise and Pershing II missiles in Europe – helped keep the Atlantic alliance together at a crucial moment. Hammering out this agreement, in which the two leaders played a central role, was a truly significant achievement.

All the same, in 2016, the Schmidt-Carter story is perhaps a reminder that a foreigner, even an ally, should keep their mouth shut during a US presidential election campaign.

Featured image credit: “President Jimmy Carter at his desk in the Oval Office: nlc00251 Carter bl&wh” by Children’s Bureau Centennial. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A prickly pair: Helmut Schmidt and Jimmy Carter appeared first on OUPblog.

Why hasn’t the rise of new media transformed refugee status determination?

Information now moves at a much greater speed than migrants. In earlier eras, the arrival of refugees in flight was often the first indication that grave human rights abuses were underway in distant parts of the world. Since the advent of the Arab Spring in 2011, the role of new and social media as agents of transformation has become a staple of global assumptions about the power of technology to diversify political expression and facilitate networks for social change. The events of that year also triggered a heightened awareness of the promise of technology to bear witness to human rights violations.

By arming ‘citizen journalists’ with so called ‘liberation technology’ there is now capacity to document human rights abuses on an unprecedented scale. Given the need for better and more individualized evidence of rapidly evolving situations in refugee-producing states, what has been the impact of e-evidence on refugee status determination (RSD)?

New media are conduits for better and more accessible country of origin information. Over the past decade, the production and consumption of human rights documentation in refugee-producing countries has in theory been universalized by new technologies. Diminished costs and rising access have pluralized, if not fully democratized, the use of technology and information, and have increased and diversified the range of actors involved in the communications revolution. Paradoxically, for the many asylum seekers who claim a well-founded fear arising from events that are off the ‘radar’ of mainstream human rights reporting, this creates considerable challenges in terms of establishing the credibility of their claims. A framework for human rights reporting that still leaves much unreported has consequences in a world that presumes the reverse, given the overflow of information through the Internet. In the context of country of origin conditions, immigration lawyer Colin Yeo argues that this overflow ‘imbues us with dangerously false omniscience’.

Emerging technologies have, in principle, radically expanded the sources of country of origin information accessible to asylum seekers and decision makers, and narrowed the time in which information is received. Their potential, however, is significantly under-realized. The process of identifying country of origin information from new media sources is proving to be cumbersome, demanding expertise, time, and resources that are beyond the capabilities of officials and claimants alike.

Notwithstanding this, RSD authorities increasingly expect that sufficient information will be available that can meet the standards of evidence required to corroborate testimony in genuine asylum applications. In the United States, the RSD process increasingly relies upon the provision of expert reports and corroborating documentation to supplement the core of a claimant’s testimony. Yet underlying the expectation of corroboration is the presumption that such information will be available in the first place, given the resources accessible, with a few clicks of a mouse. Many asylum seekers are ill-equipped to provide this evidence, and when it is presented in the form of new media, decision-makers are disinclined to assess it. When addressed by the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) in its guidelines on processing country of origin information, new media was identified as a ‘dubious’ evidence source. Within RSD, the potential of the Internet and new technology is compromised by the fact that they fail to satisfy two of the core criteria for evidence required with respect to country of origin information: traceability and reliability of the source. It is not surprising that EASO’s perspective is shared widely by national decision-making authorities.

The tools of documentation include not only the Internet and new media, but a wide range of new communications and digital technology, including smartphones. These new technologies allow for real-time collection of human rights evidence as events unfold and abuses are committed, changing the way we witness and document human rights violations. Real-time human rights reporting in the cybersphere should, in principle, make it more difficult for country of origin information to acquire what Guy Goodwin-Gill and Jane McAdam have described as the ‘artificial quality of freezing time’, whereby decision makers accord single events a distorted significance. External sources of information from the Internet reflect the fluid nature of human rights situations and extend beyond traditional reports of media, NGOs, and civil society. The consequent volume of material is overwhelming. Roughly 30,000 new information items are added to UNHCR Refworld and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin Information (ACCORD) each year. This implies access to more than 300,000 documents covering country of origin information and refugee-related legal and policy instruments, cases, and materials.

The potential of this abundant country of origin information and corroborative evidence depends on whether it can be accessed effectively, and if it can be authenticated and found to be reliable. E-evidence that asylum seekers can use to corroborate their oral testimony includes: official documents; digitally generated images and encoded audio and video recordings; ‘born-digital’ format files such as text and word processing files; crowd-sourced information such as web pages, blogs, Twitter posts, and other social media; networked communications such as email and text messages; and content recorded on mobile phones. As O’Neill et al note in their comprehensive examination of the complexities that attach to the use of e-evidence in criminal prosecutions, each type of e-evidence has different technical indicators of authenticity and reliability. In international human rights fora, the methods used to assess e-evidence are determined on a case-by-case basis in the absence of rules that address the categorical distinctions between sources of technology. Given the propensity for technology to outpace directive guidelines, this discretionary approach towards e-evidence is largely adopted by domestic courts and by administrative regimes responsible for asylum. Consequently, there is no standard protocol on e-evidence to guide RSD.

The power of e-evidence is linked to the capacity of individuals and organizations to satisfy the criteria required for effective authentication and reliability. The expertise required for this is not to be presumed, since it involves technical skills related to methods of collection and preservation, authentication practices, and chain of custody procedures. Organizations training NGOs in this field are strikingly few. For human rights evidence to be legally viable, there must be widespread grassroots awareness of the technical criteria that will be applied to e-evidence in legal fora, be they national or international criminal courts, human rights bodies, or RSD authorities. The challenge for the international human rights community is to construct an effective training framework to enhance the quality of e-evidence.

Headline image credit: Humanitarian Aid in Congo, November 2008, by Julien Harneis. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why hasn’t the rise of new media transformed refugee status determination? appeared first on OUPblog.

MOOCs and higher education: evolution or revolution?

Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) burst into the public consciousness in 2012 after feverish press reports about elite US universities offering free courses, through the Internet, to hundreds of thousands of people worldwide. A Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) course on Circuits and Electronics that had attracted 155,000 registrations was a typical example. Pundits proclaimed a revolution in higher education and numerous universities, and, fearful of being left behind, joined a rush to offer MOOCs.

Specialist organisations such as Coursera and edX provided the information technology (IT) platforms to support MOOCs, because managing electronic communication with hundreds of thousands of learners worldwide was beyond the IT capabilities of all but the largest open universities. Today MOOC platforms are available in countries across the world. The UK’s FutureLearn consortium, for example, has 80 partner universities and institutes, which offer hundreds of MOOCs to over 3 million people.

Four years after the MOOCs craze began, where are we today? MOOCs provide a good example of our tendency to overestimate the significance of innovations in the short term whilst underestimating their long-term impact. The early predictions of a revolution in higher education proved false, and the idea that MOOCs could be the answer to the capacity problems of universities in the developing world was especially silly. Nevertheless, MOOCs are a significant phenomenon. Over 4,000 MOOCs are available worldwide and register 35 million learners at any given time. As they have multiplied they have diversified, so that, as this cartoon implies, the meaning of every word in the acronym MOOC is now negotiable.

Although I deprecate wild assertions about the revolutionary impact of MOOCs, I am a regular MOOC learner myself, and have just registered for my 13th FutureLearn course. I much enjoy these courses, which are authoritative and well produced. I am also, however, a good illustration of why MOOCs have not sparked a revolution in higher learning. MOOCs are attractive to older people like me, who already have degrees and do not seek further qualifications, but who remain eager to acquire basic knowledge about an eclectic range of new topics. My own MOOCs have included: Writing Fiction, Challenging Wealth and Income Inequality, Childhood in the Digital Age, The Controversies of British Imperialism, Strategies for Successful Ageing, and Mindfulness.

The major role of MOOCs seems now to be evolving away from higher education. Instead they are becoming a major tool for development education in countries such as India, which is using MOOCs to improve the skills of millions of agricultural workers, and has created a nationwide assessment system to validate the knowledge that the learners have gained.

MOOCs are a significant phenomenon. Over 4,000 MOOCs are available worldwide and register 35 million learners at any given time.

So MOOCs themselves are not a revolution in higher education but they are having multiple knock-on effects in the way that it is offered. They have sparked a steady increase in the offering of all types of academic programmes online, stimulated trends towards shorter courses, and an expanded range of credentials.

With respect to online teaching, the offering of MOOCs by elite US institutions in 2012 suddenly made distance learning respectable. Although the many distance-teaching universities created worldwide on the model of the UK Open University from 1970 onwards gave access to higher learning to millions, they had little impact on the way that existing universities operated. Distance learning still suffered from the poor image of correspondence education. But once Harvard, MIT, and Stanford went online the established universities sat up and took notice. Online enrolments in regular programmes had been growing steadily since 2000 in a somewhat haphazard manner, but following the MOOCs frenzy in 2012 a survey in 2015 could declare that “online learning in higher education now mainstream.”

The wider impact of MOOCs on academic programmes and course formats has occurred as institutions try to address the two major weaknesses of MOOCs. The first weakness is that MOOCs do not provide the institutions offering them with a clear business model because they are offered free. The commonest ways of addressing this challenge are to use MOOCs as publicity for other courses that do charge fees and/or to offer certificates of participation. These documents sell surprisingly well despite lacking the credibility of the formal degree or diploma certificates that universities provide for their formal credit courses.

That is second weakness of MOOCs. They do not lead to formal credentials, which is why they are unattractive to regular undergraduate students. Early attempts to offer MOOCs to undergraduates in China flopped because the students were looking for marketable qualifications backed by their institutions.

The trends towards shorter courses and a greater variety of credentials are not solely due to MOOCs. For example, Open Badges, software that allows any organisation to certify the acquisition of skills and knowledge emerged at the same time as MOOCs. Nevertheless, the experience of offering MOOCs has undoubtedly made university teachers realise the value of shorter courses. Many have changed the way that they teach their regular courses as a result. This has made institutions more amenable to requests from employers for shorter courses related to workplace needs and credentials other than full degrees.

Featured image credit: Crowd by James Cridland. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post MOOCs and higher education: evolution or revolution? appeared first on OUPblog.

A new European Regulation on insolvency proceedings

In June 2015, EU Regulation 2015/848 of 20 May 2015 on insolvency proceedings entered into force. This Regulation reformed – or, to be more precise, recast – EC Regulation 1346/2000, in order to tackle in a much more modern way cross-border insolvency cases involving at least one Member State of the EU (except Denmark). Practitioners and academics had awaited this reform anxiously: first, because Regulation 1346/2000 was hardly the first attempt to regulate cross-border insolvencies at a European level; secondly, because the present socio-economic scenario is very different from that existing at the time of Regulation 1346/2000. The present-day scenario is characterized by a severe economic crisis and by a consequent new tendency in insolvency law towards rescuing distressed firms and discharging over-indebted individuals by means of an array of regulatory instruments. These sometimes involve courts at every stage of the procedure; sometimes they involve courts at only some stages; sometimes they do not involve them at all.

Like Regulation 1346/2000, Regulation 2015/848 does not aim at harmonizing national insolvency laws across Europe, but only at providing international private law rules. This implies that, like Regulation 1346/2000, Regulation 2015/848 contains for the most part rules of European uniform private international law concerning jurisdiction, applicable law, and the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments.

It is immediately apparent that Regulation 2015/848 is a significant improvement on Regulation 1346/2000.

The rules concerning jurisdiction are crucial. Consider the following example. Company A has its registered office in Germany; it runs its business mostly in Italy; and it has most of its assets in France. Let us suppose that this company becomes insolvent, and that it does not pay a creditor who is resident in Italy. Understandably, this creditor would prefer to apply to an Italian court for the opening of an Italian insolvency proceeding. But here an important question arises: may this creditor apply to a court in Italy? And, further, what happens if the company decides to prevent the opening of a bankruptcy proceeding and attempts to be rescued? Has this company the right to choose the jurisdiction which is most rescue-friendly?

The rules concerning the applicable law are also important. Regulation 2015/848 seeks to synchronize jurisdiction and applicable law, with the result that – as a general rule – the Italian court applies Italian law, the German court applies German law, and so on. Though this choice of policy seems to be the most reasonable, this is not always the case. Suppose that the court of Cologne has opened insolvency proceedings against a German company, and suppose again that a creditor of that company has secured its claim by means of an English floating charge. Which law will allow that creditor to enforce that security? Will it be German law, which does not “know” floating charges? Will it be English law, which has no connection with the German proceeding? Are they both applicable? And, if yes, how and to what extent?

Finally, Regulation 2015/848 contains some prescriptions concerning the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments. On this point, Regulation 2015/848 lays down a simple and effective rule which could be summarized as follows: any judgement opening insolvency proceedings in one Member State automatically produces the same effects in any other Member State. Regulation 2015/848 further supplements this prescription with a legal framework allowing the insolvency practitioners appointed in the insolvency proceedings which have been opened to enforce their rights abroad and, if necessary, to be assisted in performing this task by local authorities. Specific rules of enforcement are also provided for cases where secondary insolvency proceedings are opened.

It is immediately apparent that Regulation 2015/848 is a significant improvement on Regulation 1346/2000. Not only does Regulation 2015/848 contain almost twice as many articles as Regulation 1346/2000, plus eighty-nine recitals, and four annexes, it also elucidates many doubts concerning the application of Regulation 1346/2000 and regulates a number of issues which had not previously been addressed. For example, Regulation 2015/848 enlarges the scope of Regulation 1346/2000; it provides a detailed regime to ascertain the centre of main interests (COMI) and to challenge the decision of opening insolvency proceedings on the grounds that the court seised lacks jurisdiction; it introduces a regulation on the jurisdiction for the so-called “related actions”; it establishes a detailed regime on coordination and cooperation aimed at achieving a smoother interplay between the main and the secondary proceedings; it regulates the practice by which the insolvency practitioner in the main proceedings may “swap” a local creditor’s agreement not to request the opening of secondary proceedings with the insolvency practitioner’s promise that the distribution of the debtor’s local assets will be distributed in accordance with local national law; it provides an interconnection of insolvency registers across Europe; it standardises the procedures aiming at lodging claims; and last but not least, it regulates the insolvencies of multinational groups of companies – the first time that such a measure has been achieved anywhere in the world by means of a hard law instrument.

The date of entry into force of EU Regulation 2015/848 does not coincide with the date when it becomes applicable. In fact, Art 92 lays down that Regulation 2015/848 “shall apply from 26 June 2017”, with the exception of some articles which will become applicable from June 2016, June 2018 and June 2019, respectively. This system of vacation and staged applicability makes sense. It gives practitioners time to grasp the rationale of the new prescriptions and to interpret them systematically in the light of decisions made by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU); these still maintain their authoritative role – Regulation 2015/848 has technically recast, but not reformed, Regulation 1346/2000.

Featured image credit: Untitled, by Didlier Weemaels. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post A new European Regulation on insolvency proceedings appeared first on OUPblog.

April 25, 2016

Prince and “the other Eighties”

Prince died Thursday, and I am sad.

I’ve been asked to write about his death, but staring at the empty expanse beyond the flashing cursor, all I really know how to say is in the line above.

Plenty of writers, more ably than I could, have written and spoken movingly about Prince since his death. There’s Stephanie Dunn at NewBlackMan, Jes Skolnik at Medium, Carvell Wallace at MTV.com, Dodai Stewart at Fusion, Hua Hsu at The New Yorker, Marc Bernadin at the LA Times, Rob Sheffield at Rolling Stone, Peter Coviello at the LA Review of Books, Ann K. Powers at NPR, John Moe at The Current, Anil Dash on Twitter, Frank Ocean on Tumblr, among many, many, many more. I have listened to three separate Prince tribute podcasts today. Gawker (as it does) has already helpfully generated a Prince Thinkpiece Generator to chide the wave of post-mortems and retrospectives on the Purple One’s life and legacy. There are already listicles about the best Prince writing of the past two days, do you understand? I don’t want to offer you an inferior version of the pieces these talented and inspiring people have already written, and I’m not interested in participating in the process that requires the rendering of searing grief into “hot takes.” I don’t want to do any of that today.

Still.

Prince died on Thursday, and I am very sad. And chances are, if you are reading this, you are sad too.

I want to talk about our shared sadness, and about those who cannot share in it. Matt Thomas, a friend, scholar who has published on Prince, and a must-follow on Twitter, regularly plugs in topical news terms of the day to Twitter’s search function, adding the phrase “my professor.” His results today attest to the enduring cultural power Prince has, and the shock and distress caused by his passing.

But these results are also fascinating because of the reactions of the students, all at once puzzled and distressed, a mixture of pity and bemusement that stems from, I think, from a missing context that would help them understand why Prince is so important to so many of us today.

When my teacher found out Prince died pic.twitter.com/biNapKWJBU

— ✨ diamond ✨ (@shvrdae) April 21, 2016

What the students marveling at their teachers’ grief don’t–maybe can’t–understand is that Prince was more than just a guy who sold a lot of records and wore a lot of purple. For people left out of the 1980s neoconservative vision of what America should, he was a beacon, guiding us through this thing called life. Professionally, he was able to traverse the rigid boundaries of genre (is he funk? new wave? rock? pop?) and of labor (was he a pop star? a songwriter? a producer? a record promoter? a mogul?) constructed by the increasingly corporatized entertainment industry in a particularly risk-averse mood (post disco, post punk). He did so while simultaneously transcending, sometimes through his music and sometimes through sheer embodiment, his culture’s expectations of race, gender, and sexuality. He was, in so many ways, a sign o’ the times, a symbol of ecstatic difference in a culture that was busy selling itself a fantasy of homogeneous “family values,” and an anchor to hold onto for those who never bought in to the swindle. This is the Prince I wept for yesterday, and I am willing to bet I was not alone.

When colleagues in film and media studies found out that I was writing a book about the 1980s, the assumption was that my work would be all about corporatization and Reaganism. When my students talk to me about anti-racist movements, or the importance of queer representation in popular media, they’re often unaware of how those issues were part of the cultural conversation in the 1980s as much as they were in the 1960s, and as much as they are today. Popular memory, it seems, has reduced the 1980s to nothing more than a Gordon Gekko soundbyte, all corporate greed and neoconservative politics. But the 1980s had Prince, just like they had Spike Lee and John Waters and Joe Strummer and Joan Jett, just like they had ACT UP and marches for nuclear disarmament and divestment from apartheid South Africa. Prince is, in other words, an icon of “the other Eighties,” the one that is not chronicled on cable-television retro programming and reductive historical narratives. It’s important to remember, after all, that even in times of political retrenchment, people have always joyfully resisted restrictive and repressive forms of both politics and culture.

My apartment in Philadelphia is set above a fairly busy intersection. All evening, as I’ve sat on the patio writing this, I’ve smiled as automobiles have queued up at the traffic signal, with Prince songs blaring from their car stereos: “Why You Wanna Treat Me So Bad” and “When You Were Mine,” “Cream,” “Kiss” and “Head,” “Seven” and “Raspberry Beret,” “Musicology” and “Baltimore.” It’s been lovely, really. But part of my job as a scholar of media and cultural studies, I think, is not only to document what songs or films or musicians or actors are important, but also to convey how these pieces of public culture responded to, influenced, resisted and remade the culture that surrounded them. Prince died Thursday, and we are sad, but it is our privilege not just to celebrate and mourn him—though he definitely warrants plenty of both—but also to carry on his legacy of being a beacon to others.

Image credit: Prince at Coachella, 2008. Photo by Micahmedia at en.wikipedia. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Prince and “the other Eighties” appeared first on OUPblog.

The quest for a malaria vaccine continues

The 2016 World Malaria Report estimates that there were approximately 215 million cases of malaria and 438,000 deaths in 2015. The majority of deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa and among young children, and malaria remains endemic in around 100 countries with over three billion people at risk. Over the past 15 years there have been major gains in reducing the global burden of malaria; however, it continues to be a major cause of mortality and morbidity globally. The 25th of April marks World Malaria Day, highlighting key issues in the fight against this major disease. Plasmodium falciparum causes the bulk of malaria, with P. vivax being a second major cause. World Malaria Day 2016 highlights the need for innovation to develop effective vaccines, new drugs, and better diagnostics to ensure continued success towards malaria elimination.

An effective vaccine has long been a goal of the global community, and the tremendous benefits of low cost, safe, and highly effective vaccines have been demonstrated with other infectious pathogens. The WHO Malaria Technology Roadmap sets out the goals for malaria vaccine development with the aim of achieving a licensed vaccine with >75% efficacy by 2030 (vaccine efficacy is usually expressed as the proportion of malaria episodes prevented), and vaccines that reduce malaria transmission to facilitate malaria elimination. However, achieving highly efficacious vaccines has proved exceptionally challenging.

The most advanced vaccine, known as RTS,S, and the only malaria vaccine to have progressed through formal phase III trials, showed significant, but modest, efficacy of 26-36% among infants and young children even with a booster dose (efficacy varied by age group). RTS,S is based on using a single antigen of P. falciparum. One strategy to develop more efficacious malaria vaccines is to incorporate multiple antigens across different life stages of the parasite. The infection commences with the bite of an infected mosquito (Anopheles spp only), which inoculates the sporozoite stage; this is the stage targeted by the RTS,S vaccine. Sporozoites travel to the liver where they infect hepatocytes and replicate inside them for seven to ten days, before daughter parasites are released to enter the blood stream to commence the blood-stage of infection. It is during this stage that malaria disease develops as Plasmodium spp infect red blood cells and replicate inside them.

The majority of deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa and among young children, and malaria remains endemic in around 100 countries with over three billion people at risk.

Developing vaccines that target the merozoite to block infection of red blood cells is an attractive approach to preventing blood-stage replication and clinical disease. The merozoite is highly complex and the process of red blood cell infection involves multiple proteins and interactions. This complexity has proved challenging to our efforts to understand merozoite invasion and malaria immunity, as well as to developing merozoite antigens as malaria vaccines.

Over recent years, major progress has been made in understanding red blood cell invasion by merozoites, as well as the nature and targets of immune responses that block infection. This has enabled the identification of several promising vaccine candidates. A number of candidate vaccine antigens have shown significant promise in animal and in vitro models and a few have shown efficacy in clinical trials establishing a proof-of-concept for this strategy. Effective immunity appears to involve multiple different immune mechanisms, including the ability of antibodies produced by the immune system to directly block merozoite function, recruit complement proteins from the blood to kill or inactivate merozoites, and interact with leukocytes to clear infection. Through this expanding understanding of infection and immunity, developing vaccines that target both the merozoite and sporozoite forms might help achieve the goal of high efficacious vaccines in the future.

The persisting challenges faced in malaria control and elimination, including escalating drug resistance, insecticide resistance, and insufficient funding further strengthen the importance of the long term goal of developing highly effective malaria vaccines to protect humanity from one its greatest foes.

Featured image credit: ‘Mosquito’ by Tom. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The quest for a malaria vaccine continues appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers