Oxford University Press's Blog, page 519

April 21, 2016

The ingenious gentleman from Don Quixote

This extract is taken from Don Quixote de la Mancha, to celebrate the life of Cervantes, who died on 22 April, 1616 – four hundred years ago.

In a village of La Mancha,* the name of which I purposely omit, there lived not long ago, one of those gentlemen, who usually keep a lance upon a rack, an old target, a lean horse, and a greyhound for coursing. A dish of boiled meat, consisting of somewhat more beef than mutton, the fragments served up cold on most nights, an omelet* on Saturdays, lentils on Fridays, and a small pigeon by way of addition on Sundays, consumed three-fourths of his income. The rest was laid out in a surtout of fine black cloth, a pair of velvet breeches for holidays, with slippers of the same; and on week-days he prided himself in the very best of his own homespun cloth. His family consisted of a housekeeper somewhat above forty, a niece not quite twenty, and a lad for the field and the market, who both saddled the horse and handled the pruning-hook. The age of our gentleman bordered upon fifty years. He was of a robust constitution, sparebodied, of a meagre visage; a very early riser, and a keen sportsman. It is said his surname was Quixada, or Quesada (for in this there is some difference among the authors who have written upon this subject), though by probable conjectures it may be gathered that he was called Quixana.* But this is of little importance to our story; let it suffice that in relating we do not swerve a jot from the truth.

You must know then, that this gentleman aforesaid, at times when he was idle, which was most part of the year, gave himself up to the reading of books of chivalry, with so much attachment and relish, that he almost forgot all the sports of the field, and even the management of his domestic affairs; and his curiosity and extravagant fondness herein arrived to that pitch, that he sold many acres of arable land to purchase books of knight-errantry, and carried home all he could lay hands on of that kind. But, among them all, none pleased him so much as those composed by the famous Feliciano de Silva: for the glaringness of his prose, and the intricacy of his style, seemed to him so many pearls; and especially when he came to peruse those love-speeches and challenges, wherein in several places he found written: ‘The reason of the unreasonable treatment of my reason enfeebles my reason in such wise, that with reason I complain of your beauty’:* and also when he read—’The high heavens that with your divinity divinely fortify you with the stars, making you meritorious of the merit merited by your greatness’.

With this kind of language the poor gentleman lost his wits, and distracted himself to comprehend and unravel their meaning; which was more than Aristotle himself could do, were he to rise again from the dead for that purpose alone. He had some doubt as to the dreadful wounds which Don Belianis* gave and received; for he imagined, that notwithstanding the most expert surgeons had cured him, his face and whole body must still be full of seams and scars. Nevertheless he commended in his author the concluding his book with a promise of that unfinishable adventure: and he often had it in his thoughts to take pen in hand, and finish it himself, precisely as it is there promised: which he had certainly performed, and successfully too, if other greater and continual cogitations had not diverted him.

He had frequent disputes with the priest of his village (who was a learned person, and had taken his degrees in Sigiienza*) which of the two was the better knight, Palmerin of England,* or Amadis de Gaul.* But master Nicholas, barber-surgeon of the same town, affirmed, that none ever came up to the Knight of the Sun,* and that if any one could be compared to him, it was Don Galaor, brother of Amadis de Gaul; for he was of a disposition fit for everything, no finical gentleman, nor such a whimperer as his brother; and as to courage, he was by no means inferior to him. In short, he so bewildered himself in this kind of study, that he passed the nights in reading from sunset to sunrise, and the days from sunrise to sunset: and thus, through little sleep and much reading, his brain was dried up in such a manner, that he came at last to lose his wits. His imagination was full of all that he read in his books, to wit, enchantments, battles, single combats, challenges, wounds, courtships, amours, tempests, and impossible absurdities. And so firmly was he persuaded that the whole system of chimeras he read of was true, that he thought no history in the world was more to-be depended upon. The Cid Ruy Diaz,* he was wont to say, was a very good knight, but not comparable to the Knight of the Burning Sword,* who with a single back-stroke cleft asunder two fierce and monstrous giants. He was better pleased with Bernardo del Carpio for putting Orlando the Enchanted to death in Roncesvalles, by means of the same stratagem which Hercules used, when he suffocated Anteus, son of the Earth, by squeezing him between his arms.* He spoke mighty well of the giant Morgante;* for, though he was of that monstrous brood who are always proud and insolent, he alone was affable and well-bred: but, above all, he was charmed with Reynaldos de Montalvan,* especially when he saw him sallying out of his castle and plundering all he met; and when abroad he seized that image of Mahomet, which was all of massive gold, as his history records. He would have given his housekeeper, and niece to boot, for a fair opportunity of handsomely kicking the traitor Galalon.*

Feature Image: Don Quixote by Gustave Doré. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post The ingenious gentleman from Don Quixote appeared first on OUPblog.

Shifting commemorations, the 1916 Easter Rising

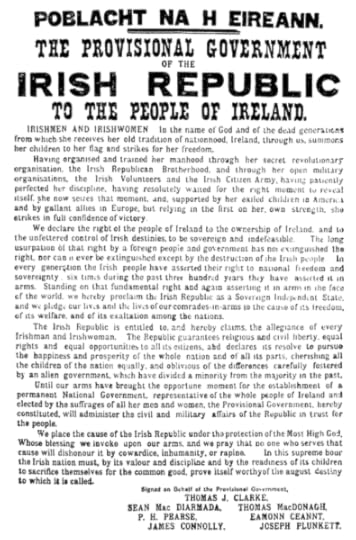

This Easter, Dublin experienced the culmination of the commemorative activities planned for the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising. There was the traditional reading of the Proclamation in front of the General Post Office (GPO), the military parade, and a series of talks and seminars, held at various locations of historical and national significance. These celebrations form the latest culmination of a shifting attitude to the Rising’s commemoration in Ireland, born out of complex interactions of party politics, Irish nationalism, and wider events.

The current round of celebrations actually started in 2012, and has been partly or wholly sponsored by the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. It is interesting to see how this government agency has approached the issue, encouraging the emergence of a more inclusive national narrative – one which incorporates the heroes and great deeds of ‘the other side’, as well as those that helped create the Republic. Thus, the commemorative cycle opened with the centenary of the 1912 Ulster Solemn League and Covenant, despite it being traditionally perceived as the nemesis of nationalism, the event that made Partition inevitable and ensured the defeat of the revolution in the North.

Such an approach is one of the outcomes of the political and cultural changes that have completely transformed the two Irelands since 1990, including not only the Peace Process in the North, but also the impact of the Mary Robinson and Mary McAleese presidencies in the South. Together, the two leaders spearheaded the emergence of a pluralist vision of the nation, championing minorities and diversity against the old nationalist mono-culturalism. This had an effect on the question of commemoration, which increasingly involved a public acceptance of the Unionist heritage. For example, under McAleese, celebrating ‘the Twelfth’ (the 12th of July, the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne) became an annual event at the Áras an Uachtaráin, with a reception for representatives of the Orange Order and historical reenactments of the battle. Then, the Queen’s visit to the Republic in 2011 had a momentous impact, which further encouraged a more ecumenical approach to the past. While official attitudes relaxed, there was also a parallel groundswell of local initiatives, driven by groups or private individuals aiming to reclaim the First World War as an ‘Irish’ war. It came with a sense of pride in the military record of the regiments disbanded in 1922, such as the Connaught Rangers or the Royal Munster Fusiliers (often represented by associations devoted to preserving and honoring the memory of these units).

Image credit: The Easter Proclamation of 1916 by Jtdirl. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: The Easter Proclamation of 1916 by Jtdirl. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.In this context, the meaning of 1916 was bound to change. However, it had been steadily changing almost continuously since the Rising itself. In the 1920s, the commemoration consisted primarily of a Catholic Mass celebrated on Easter Sunday (rather than on the actual date of the Rising, the 24th of April) and attended by the survivors of the rebellion and their families and friends. For years it was a smaller-scale affair than Remembrance Day, which attracted large crowds throughout the 32 counties.

One of the reasons was that the Easter Rising presented difficulties for both main Southern political parties and their leaders. Though Eamon De Valera was a 1916 veteran, from the end of the Civil War (1923) he had moved away from revolutionary violence, and in 1926 established Fianna Fail as a constitutional republican party, increasingly ill-at-ease with the still-active IRA. The latter used the commemoration to assert the continuing legitimacy of armed struggle, something that De Valera could no longer contemplate. Therefore, from 1935 he started to reclaim the Rising for the state, with a GPO ceremony and an Irish Army parade, a military display whose aim was to seize the physical and political space hitherto occupied by the IRA. It was the first step towards a systematic and ruthless suppression of the group in the 26 counties, an operation completed by the early 1940s.

For the same reasons – a concern for the stability of democracy and state power against paramilitary activism – about thirty years later, another Fianna Fail government discontinued the military parade, as the government wanted to express their rejection of military answers to the Northern Irish question.

Equally complex was the attitude to commemoration displayed by Fine Gael, the other major political party. For decades neither the party founder, the 1916 veteran W.T.Cosgrave, nor his successors attended the annual GPO ceremony. They started to do so only in 1965, one year before the 50th anniversary of the Rising and in the context of thawing relations with Northern Ireland, which made violence look reassuringly obsolete. However within three years the onset of the Northern Irish Troubles again changed the approach to the commemorations, sparking off a series of strong Fine Gael reactions against militant nationalism because of its renewed relevance and popular appeal.

Fine Gael had to wait nearly fifty years before its moment to reinterpret the Rising finally came. This was in the aftermath of their victory in the 2011 election, which ensured that the party would be in office during the years leading up to centenary. However, what they did was in broad continuity with the line adopted by their Fine Fail predecessors. Rather than making a new start, the Fine Gael-Labour government further encouraged a pluralist approach to the event, a development facilitated by Enda Kenny’s choice of Heather Humphreys – who once described herself as ‘proudly Presbyterian and proudly Republican’ – as his Minister for Arts, Heritage, and the Gaeltacht.

Such a politically charged, but continuously changing tradition of government engagement with commemoration is fascinating for historians. In its practical effects, it has pitfalls, however it also has its advantages, particularly in the context of 2016. For a post-Catholic, increasingly multi-cultural Ireland makes it easier for historians to speak and write about the Irish Revolution through different frameworks of interpretation, from shifting the focus away from the anti-British dimensions of the revolution and towards its positive demands, to analyses that place the Rising within the context of rebellions and revolutions between 1917 and 1923. We could think of more examples, for both the Rising and the Irish Revolution deserve close scrutiny as an illustration of one of the most significant forces in the transformation of the era in which we live –one which, unlike state socialism, is not going to disappear soon – namely, the global rise of democratic nationalism.

Image credit: 1916 Commeration of the Easter Rising Wreath Laying at GPO by Irish Defence Forces. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Shifting commemorations, the 1916 Easter Rising appeared first on OUPblog.

Protecting the Earth for future generations

Earth Day is an annual celebration, championed by the Earth Day Network, which focuses on promoting environmental protection around the world. The Earth Day Network’s mission is to build a healthy, sustainable environment, address climate change, and protect the Earth for future generations. The theme for Earth Day 2016 is Trees for the Earth, raising awareness around protecting the Earth’s forests – with an aim to plant 7.8 billion trees by 2020. Taking place on 22 April, Earth Day has been celebrated since 1970, in over 192 countries.

To celebrate, we’re offering a selection of related content for you to explore and enjoy, including journal articles, special and virtual issues, blog posts, and much more. Join the discussion in the comment section below or by following the Twitter hashtag #EarthDay2016.

You can discover more about environmental protection by exploring our Earth Day 2016 collection page.

Featured image credit: Forest road, by valiunic. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Protecting the Earth for future generations appeared first on OUPblog.

April 20, 2016

Bosom, breast, chest, thorax… Part 2

To reconstruct an ancient root with a measure of verisimilitude is not too hard. However, it should be borne in mind that the roots are not the seeds from which words sprout, for we compare such words as are possibly related and deduce, or abstract their common part. Later we call this part “root,” tend to put the etymological cart before the horse, and get the false impression that that common part generates or produces words. The plant metaphor in linguistics (word roots, stems, trees, language branches, and so forth) has in general little to recommend it despite its venerable age and the clear message of its inner form. (The German noun Stammbaum appears even in English dictionaries.)

Language tree: A colorful but somewhat misleading metaphor.

Language tree: A colorful but somewhat misleading metaphor.So what is the “root” of the word breast? Among the words close to breast we find burst, from bersten, in which er owed its existence to metathesis (the transposition of e and r). As follows from the cognates elsewhere in Germanic, the verb’s protoform must have been brestan. The similarity between Old Engl. brēost and brestan is unmistakable, and nearly all the older dictionaries that feature this word connect breast with burst. The reservation (…that includes this word…) is not a tribute to pedantry. For example, Stephen Skinner (1671) and a later anonymous dictionary (Gazophylacium) skipped breast. Junius (1743, a posthumous edition) mentioned it but offered a fanciful etymology from Greek. The others, including Skeat (in the first edition of his great dictionary), stuck to burst.

But why should the breast burst? One could think of a human breast bursting with grief along the Byronic lines:

Or else this heavy heart will burst.

Or else this heavy heart will burst.“But bid the strain be wild and deep,

Nor let thy notes of joy be first:

I tell thee, Minstrel, I must weep

Or else this heavy heart will burst;

For it hath been by sorrow nurst,

And ached in sleepless silence long;

And now ‘tis doomed to know the worst,

And break at once—or yield to song”

(“My Soul Is Dark,” from his Hebrew Melodies)

In principle, a poetic word, ancient or modern, for “breast” as the seat of passion is quite possible: compare the specification of Engl. bosom, (to a certain extent) Greek kólpos, and Latin sinus. It even seems that the speakers of Germanic did have such a word, namely Gothic barms (which rendered Greek kólpos), Old High German barm, and Old Engl. bearm. The context of bearm of course does not point to a bosom ready to burst. It means “bosom, lap, breast; middle, inside,” “possessions” (in poetry), and, less clearly, “emotion, excitement” (in a psalter). “Middle, inside” are especially telling senses. Whether native or borrowed, Old Norse barmr continues into the modern Scandinavian languages (barm) as a word sometimes belonging to the elevated style or endowed with unmistakable poetic connotations. It can also mean “a woman’s breast.” Not improbably, barm goes back to the same root as the verb bear “to carry” (from beran), that is, it denotes a place where either objects or feelings (!) could be hidden.

The German verb erbarmen “to move to pity” is known to have the root arm, not barm, for it glossed Latin miserere “to have pity” (arm means “poor”), so that the original form was er-b-armen. A similar process happened in Old English, but I cannot get rid of the suspicion that at least in Old High German the existence of barm contributed to the verb’s meaning “to move to pity.” If Gothic barms and its cognates sometimes referred to the breast as the seat of emotions, breast must have had a different meaning. Skeat (1882; actually 1879, because his etymological dictionary appeared in installments) wrote: “The original sense is a bursting forth, as applied to the female breast in particular.” We have already witnessed the attempt to explain bosom in the same terms. The female breast poses a great temptation even to grey-haired historical linguists. But as with bosom, there is no evidence that in old days breast referred to a woman’s body. Neither did barm, despite such an application of it in Modern Norwegian. Etymology, as I have noted more than once, makes great progress: as times goes on, it becomes more and more careful. In the last edition of his dictionary (1910), Skeat dismissed breast as a word of unknown origin. Some authorities followed his example.

Is this the ultimate inspiration for the word breast? Unlikely.

Is this the ultimate inspiration for the word breast? Unlikely.Alongside burst (that is, brestan), verbs like Middle High German briezen “to bud, burgeon” (z = ss) have been proposed as supplying the clue to the origin of breast. The reference would be to the nipples on the breast, not necessarily of a woman. A similar conjecture also turned up in the works discussed in connection with bosom, which is not surprising: bosom and breast are close. Today most researchers share the idea that breast was named after its “buds.” In this light, the proto-Indo-European root had the form breu–s “to swell,” and again we find ourselves on familiar ground! It will be remembered that I tried to make a case for “swell” as the foundation of the word for bosom. No doubt, breast and bosom might have synonymous roots, mean more or less the same, and later acquire somewhat different meanings.

Facts, not opinions, matter in etymology, but what I am going to say is just that: an opinion. I believe that breast was not coined because a human breast has two nipples or two teats, though the ancient neuter dual might arise thanks to the clear division of the human breast into two sections. It probably emerged because it swells, rather than because of the sprouting “buds.” Last week I mentioned the fact that the word for “breast” was related to the Slavic name for “belly” (briukho). The not uncommon emphasis on what is inside the breast points away from the upper front surface of the body. If breast emerged as “a swelling, heaving organ,” only bosom perhaps referred specifically to the upper part of our anatomy, while breast was expected to cover the entire front, from neck to groin, not from neck to abdomen, and referred to the swelling of the belly as well, for, when we breathe, it also expands. Thus, in Russian, grud’ “breast” (with cognates elsewhere in Slavic) is related to Latin grandis “big, large, ample, great.” Aristoteles’s Greek thorax designated the whole “trunk”; “breast, chest; breastplate” are the word’s later senses. It is no wonder that, when bosom and breast collided, their meanings became more or less specialized.

The bosom is soft, while the breast makes one think of ribs. To clarify this meaning, languages have words and phrases like German Brustkorb, literally “breast basket,” and Russian grudnaia kletka [stress on na] “breast case.” Engl. chest is an old word. A borrowing of Latin cista, for a very old time it meant only “box, coffer” (compare a chest of drawers, tool chest, and simply chest “coffer”). Chest “thorax” first turned up in the sixteenth century. So now we have a pain in the chest, press a child to our breast, and let our bosom heave with uncontrollable sobs. A hairy chest is what many men live with, a hairy breast is a fact of life, but a hairy bosom is impossible. Yet in many cases, all three words are interchangeable. Only thorax, borrowed in the sixteenth century (just when chest acquired its new meaning), remains a special term.

Image credits: (1) Tree silhouette. CC0 via Pixabay. (2) Simplified language tree in Swedish by Ingwik. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Joshua 1:1 in the Aleppo Codex. 10th century. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons. (4) Lord Byron, a coloured engraving. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons. (5) Tivoli, Villa d’Este:fontana di Diana Efesina, detta dell’Abbondanza. Photo by Lalupa. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Bosom, breast, chest, thorax… Part 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

Science informed by affection and ethics

“We may, without knowing it, be writing a new definition of what science is for,” said Aldo Leopold to the Wildlife Society in 1940. A moderate but still crisp April breeze was playing in my hair as the sun worked to melt the last bits of frost in the silt. Shoots of prairie grasses were popping up through the mud, past shell skeletons of river mussels and clams. A Canada goose honked reprimands for our trespassing as other waterfowl passed overhead. We felt the freedom of adventure and excitement, as though we were exploring a newly washed world (despite the occasional years- or decades-old can or pieces of glass.) There were no human footprints but ours testing the flats to see which were quicksand-like muck and which were sand beds that could hold us.

Two years before, the big decision to remove the dam in Willow River State Park in Wisconsin resulted in the loss of the lake and a new river channel cutting its way through the bottomlands. This was part of the legacy of Luna Leopold, the great hydrologist. It was he who convinced water scientists and engineers, policymakers and communities to start asking questions about dams and their effects on the river communities upstream and down–both wild and human. Out of these questions arose a movement to remove some dams and set the rivers free.

That afternoon, I was supposed to give a talk on Luna’s father, Aldo Leopold, and Aldo’s multifaceted legacy, which included that of his children, students, scholars, organizations, and ideas. But when I asked myself, should I read up to prepare or visit the park, I thought, what would Aldo do? What would any of the Leopolds do? Go to the park!

Art project on the river beach in Willow River State Park by Marybeth Lorbiecki. Used with permission.

Art project on the river beach in Willow River State Park by Marybeth Lorbiecki. Used with permission.The Leopold story is all about the ripple effects of a man who lived dedicated to enjoying, studying, preserving, and conserving those things he deeply loved – “things natural, wild, and free.” It was Aldo who started the field of wildlife management and ecology, started the US National Forest wilderness system, wrote A Sand County Almanac and proposed the “land ethic,” among so many other contributions to conservation. But it was Luna who then applied that land ethic to the rivers, and it was Aldo’s eldest son, Aldo Starker Leopold, who applied it to wildlife in the national parks. Starker’s “Leopold Report,” which called for our parks to be a showcase of the original flora and fauna, brought bison and wolves back to Yellowstone. In our 2016 celebration of our national parks, we owe Starker some memory and gratitude.

Starker and Luna were just the two eldest siblings. Then came Nina, Carl, and Estella, each of whom made pioneering contributions to the field of conservation from a unique base of scientific expertise. The Leopolds have well-earned the distinction of placing more members of the National Academy than any other family. The Leopold siblings along with their students and Aldo’s students and Leopoldian scholars, ideas, and organizations have made such a difference to our world, by infusing science with love, affection, and an ethical framework. On 21 April 2016, the day before Earth Day, it will be 68 years since Aldo’s death. And yet we are still trying to put in place his observations, including that of what the purpose of science is, as he told the Wildlife Society in 1940:

We are not scientists. We disqualify ourselves at the onset by professing a loyalty to and affection for a thing: wildlife. A scientist in the old sense may have loyalties except to abstractions, no affections except for his own kind…

The definitions of science written by, let us say, the National Academy, deal almost exclusively with the creation and exercise of power. But what about the exercise of creation and wonder…

Featured image credit: Aldo Leopold in Rio Gavilan by USFS Region 5. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Science informed by affection and ethics appeared first on OUPblog.

Long-term causes of the Eurozone crisis

The European Union is undergoing multiple crises. The UK may vote in favour of leaving the Union in June. European Union member states are in deep disagreement on various crucial issues, not only on how to handle the stream of refugees from the Near East, but also on how to combat terrorism, and how to deal with Russia. And, in each election, Eurosceptic parties garner an increasing share of the vote.

Given the urgency of these issues, the Eurozone crisis has been relegated to the background of public debates. However, the crisis is still ongoing today. The gross domestic product of the Eurozone is still lower than it was in 2008, in marked contrast to the US and the UK. Unemployment in its Southern member states, including France, is very high, with youth unemployment of more than 50% in Greece and Spain, leading to a lost generation in terms of economic and social participation.

Discussions about the origins of the Eurozone crisis have mainly been conducted within economics. Most economists agree on a number of proximate causes for the crisis. On the one hand, it is a debt crisis, with a focus on public debt in Greece and Spain, and the more severe problem of private debt in Spain. On the other hand, it is a crisis of competitiveness. The competitiveness problem has both a product and a price dimension. As for the product dimension, a number of Eurozone economies have a medium-quality production structure that has increasingly encountered massive competition from emerging economies, most notably China. In terms of price competition, unit labour costs have increased much more strongly in these Southern European economies than in Germany.

However, these proximate causes only scratch the surface of the Eurozone problem. They do not explain where the high degree of indebtedness comes from. Neither do they explain why some Eurozone economies encounter persistent competitiveness problems and are not able to mimic the successful German model. In order to identify the deeper causes of the Eurozone crisis, we need to look elsewhere. The institutionalist Comparative Capitalism tradition in political economy can assist our search.

Comparative Capitalism scholarship assumes that different national institutional contexts make for different economic capacities. More specifically, it looks at institutions such as wage bargaining, innovation, and financial systems, as well as the cross-cutting general mechanisms linking these institutions. The European Union consists of economies that can be classified into four basic types with specific combinations of these institutional features, namely the coordinated economies of, for example, Germany and Austria, the dependent economies of Central Eastern Europe, the liberal economy of the UK, and the mixed economies of Southern Europe.

There is simply too much institutional heterogeneity for a common currency in Europe.

At the core of the Eurozone crisis is the problematic co-existence of coordinated and mixed economies within one currency union. The weakness of a system of coordinated wage bargaining in the Southern European economies is a major reason for their loss of cost competitiveness, in particular with regard to the highly coordinated German economy and its focus on wage restraint. The common currency does not allow for devaluations anymore, a formerly well-established Southern European strategy in order to recover competitiveness against Northern competitors.

Moreover, the German economy, with an elaborate innovation system conducible to a specialization in high-quality manufacturing, such as advanced machinery, has strongly benefitted from the rise of emerging economies. This is in marked contrast to the Southern European economies, as it has an innovation system focusing on highly price-sensible medium-quality goods, such as garments and furniture. A common currency with the highly successful German export economy has also led to a much higher exchange rate for the Euro, compared to an imaginary Southern European currency alone, thereby aggravating the competitiveness problem with regard to the emerging economies.

The establishment of the Euro as a common currency has led to a massive decrease of interest rates in Southern Europe. This has not only enabled the Greek government to temporarily compensate for the loss of economic competitiveness by strongly increasing public debt, but also caused a construction boom in Spain, thereby leading to an explosion of private debt – and a further loss of competitiveness.

The implications of these observations on a solution for the Eurozone crisis are very bleak. The economic-institutional requirements for a fundamental improvement of the situation are hardly feasible on political grounds. A solution would require a decade of over-proportional wage increases in Germany, which is deeply unpopular with German companies and work councils. A solution would also require massive fiscal transfers within Europe, in order to upgrade production structures in the South, as well as to provide debt relief for countries such as Greece and Portugal. However, pan-European solidarity is too limited for these kinds of measures.

From the perspective of Comparative Capitalism, the Eurozone features the choice between long-term stagnation and turbulent break-up. There is simply too much institutional heterogeneity for a common currency in Europe.

Headline image credit: Europe torn flag by PeterBe. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Long-term causes of the Eurozone crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

April 19, 2016

Whatever happened to the same-sex marriage crisis in the US?

Kim Davis, the Kentucky county clerk who refused to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples after the US Supreme Court handed down the Obergefell decision, enjoyed a certain degree of celebrity in 2015. The press eagerly documented Davis’s crusade in her jurisdiction as well as her audience with the Pope. Other headlines, however, soon drew attention to Davis’s own complicated familial past. Married four times (twice to the same man) and divorced three, she also was the mother of twins, born five months after divorcing her first husband. The children were, in fact, the biological children of her third husband, but were adopted by the second, who is also the fourth. For many supporters of same-sex marriage, Davis’s seeming lack of respect for the institution that she so vehemently insisted on defending was the epitome of hypocrisy. But her story is compelling, too, for an entirely different reason. However unwittingly, Davis’s personal history reflects a current messiness–for lack of a better word–in many facets of American family life that played a key role in very decision she opposed.

At the dawn of the twenty-first century, same-sex marriage seemed destined to be a great and prolonged marriage crisis, as many Americans believed that such unions represented an assault on “family values.” Arguments in the 1990s and early 2000s against same-sex marriage repeated a number of key themes: insisting that marriage across time, place, and cultures had “always” been between “one man and one woman;” arguing that allowing same-sex couples to marry would open the floodgates to other “alternative” marriage arrangements, like polygamy and incest; and claiming that permitting same-sex marriage would do irreparable harm to heterosexual marriage. This opposition had widespread political ramifications, from the 1996 passage of the “Defense of Marriage Act” to the placement of referenda about same-sex unions on various state ballots during the hotly contested Presidential election in 2004.

“Wedding Ring” by andessurvivor. Creative Commons via Flickr

“Wedding Ring” by andessurvivor. Creative Commons via FlickrBut the same-sex marriage crisis has not had the legs that many commentators predicted it would have. By the time the Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell, survey results suggested that public support for same-sex marriage was on the rise, although significant pockets of opposition do remain, seen just last month in Missouri. (Furthermore, legal discrimination against the LGBTQ community in other arenas is still a pressing social problem.) Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion did address — and dismiss — each of the usual objections to same-sex marriage. He took aim, in particular, at the notion that same-sex marriage could hurt heterosexual marriage. He celebrated a vision of “marriage” (without any qualifiers) that assumed the superiority and normativity of the nuclear family. Highlighting “the transcendent importance of marriage,” Kennedy argued: “it is the enduring importance of marriage that underlies the petitioners’ contentions.” He held that all marriage “embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family.” Kennedy also claimed that the inability to marry had a negative effect on the offspring of same-sex couples, contending: “Without the recognition, stability, and predictability marriage offers, their children suffer the stigma of knowing their families are somehow lesser.”

Why did Kennedy focus so intently on the esteem that same-sex couples have for marriage, as well as the damage that living with unmarried parents could allegedly do to their children? It is possible that from his white, elite perspective, a different “crisis” in American marriage trumped the one posed by same sex-marriage. The enemies in this new crisis here are ones that the family values crowd would have paired with same-sex marriage in the past: cohabitation, infidelity, divorce, and out-of-wedlock pregnancies, to name a few. Marriage, while always a dynamic institution, has witnessed particularly significant changes in recent decades. Most important, various statistics suggest that marriage has declined in importance for many Americans. Indeed, historian Stephanie Coontz has gone so far as to observe in the New York Times: “Marriage is no longer the central institution that organizes people’s lives.” Census data released in 2014 suggested that there were fewer married Americans in 2012 that at any previous point in the nation’s history (from a peak of 72% in 1960 to a low of 50.5% in 2012). Well-educated Americans are increasingly more likely to be married than the less educated. And a significant number of American children, especially in the African-American community, live in single-parent households.

The Obergefell opinion, in other words, effectively works to supplant one marriage crisis with another. It suggests that same-sex marriage is not the problem of American family life in the twenty-first century. Not enough marriage, of the lifelong, monogamous variety, is. Rather than dealing with the complexities of American families as they exist in the twenty-first century (exemplified, ironically, by Kim Davis), the opinion forwards a vision of marriage that does not fully reflect reality, especially factoring in class and racial divides. Contemporary American history has been marked by heated debates over how to define, value, and defend marriage and the family. The Obergefull decision should be understood as part of this longer conversation. Furthermore, we should continue to question and interrogate the sources and meanings of declarations of marriage crisis, no matter the source.

Image credit: “Manchester Pride 2012” by Emma, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Whatever happened to the same-sex marriage crisis in the US? appeared first on OUPblog.

The evolution of evolution

How did it come to this? How was evolution transformed from a scientific principle of human-as-animal to a contentious policy battle concerning children’s education? From the mid-19th century to today, evolution has been in a huge tug-of-war as to what it meant and who, politically speaking, got to claim it. The early nineteenth-century establishment rejection of material thinking (French and revolutionary) laid the stage.

In the mid-1800s the powerful Anglican church underwent a generational shift and a certain adjustment relative to social organizing. Suffice to say that evolution was tamed and hitched to the wagon of British imperial power and to the progressives and radicals within that general cultural shadow as well. Evolutionary vocabulary concerning progress into ever-higher forms was embraced into the soft-religious, politically-empowered general society.

The most important book for content actually wasn’t Darwin’s but a fascinating volume called Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation by Robert Chambers. In 1859 and the 1860s, Darwin got folded into it via Huxley’s argument with Wilberforce, launching his name, title, and face into the symbolic leadership, specifically as an -ism for which multiple different worldviews and political priorities competed. The central figure in this process is Herbert Spencer, whose review of the Origin of Species was the primary reading (rather than the text itself), and whose terminology was vague and glowy enough to be appropriated. Today’s common view of him as a Social Darwinist obscures the history that during his time, his views were most often cited and lauded by progressives (Judson Minot Savage, Francis Power Cobbe, Auguste Comte) and have remained solidly present in that culture (in addition to the more familiar and later appropriation of his “survival of the fittest” by American industrialists). Just about everything currently called “Darwinist” in popular culture, positive or negative, is blatantly Spencerist.

Portrait of Herbert Spencer. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Herbert Spencer. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.By the 1880s, evolutionary vocabulary was massaged into various forms for a wide variety of British and American social positions and aims. When US policy attached itself to that imperial power in the 1880s, this ideology adopted evolution into American education in a muted, inspiring, glossy way, with much of its content obscured. It included safe little conundrums to wrestle over within the mainstream, not violating that larger imperial context, the most obvious being whether evolution was “for”/”about” progressive social enlightenment or capitalized profiteering.

In the mid-late 1800s, evangelical Christianity across what Colin Woodard calls Greater Appalachia was decentralized and extremely various. Its local units were split about 50-50 concerning whether evolution was the Devil or God’s work. In the 1890s, this changed dramatically with the Populist movement, when various leaders needed a unified fear-based, defiant rhetoric as an organizing device across multiple regions. Evolution served nicely toward that end–particularly regarding local vs. federal education. In the decades following the Civil War when federal schooling was instituted, including construction, teachers, and curricula, many of the regions in question saw federal policy as foreign invasion and cultural disruption. Evolution became an enemy symbol at the moment of Christian fundamentalism’s failure to exert political force. By 1900, if your evangelical church didn’t denounce it, you weren’t in the game anymore. The primary text of this movement, The Fundamentals, was written after this intellectual/political coup, in the 1910s.

Darwin’s, Huxley’s, or anyone else’s actual scientific work hardly meant a thing to this larger dialogue–the battle over whose societal plans got to be science-y and modern, and especially to claim to represent evolution-in-action. It’s a battle to exert control over what evolution, broadly speaking, means, and Darwin’s name is the figurehead for such control. Crucially, in what appeared to be mainstream “acceptance” of evolutionary theory, serious work on humans as animals was quelled. Darwin the scientist was a pioneer of studying cognition in non-humans and considering the evolutionary history of humans but that work is rarely taught. Physiological and medical work was the human priority and evolutionary content was permitted or valued only insofar as it fed into that. Everything else about being human was split across multiple topics, with evolution present in muted terms at most.

How scientists have framed evolutionary thinking in terms of meaning, or perhaps themes or motifs.

How scientists have framed evolutionary thinking in terms of meaning, or perhaps themes or motifs.The New Synthesis view of natural selection and ecology (commonly found in textbooks) is more-or-less directly from Wallace, emphasizing environmental niche as the primary driver and the beauty of “matching” of form to habitat. It formally begins with the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (resolving a perceived Darwin-Mendel contradiction), continues through clinical applications like sickle-cell, is underpinned and “crowned” by the discovery of the double helix, and includes the explanation of speciation as adaptive radiation.

The historical problem with the New Synthesis is its distortion into a simplistic, dogmatic (if elegant) view of evolutionary change. It treats evolution as a sideline or specialty rather than a founding concept for biology. Therefore the major evolutionary disciplines (systematics and ecology) became arcane and isolated even within biology throughout the New Synthesis period, which is also when our current introductory curricula and textbooks were produced. Evolution was reduced to talking-points (“the fittest survive,” “species evolve to gain advantage in their environments”) among biologists and the general populace. New Synthesis unfortunately cemented an ostensible unity, coherence, and completeness into educational dogma rather than generated new questions. Today, the body of work called evolutionary theory is more disjointed than it should be, with ideas and terms hanging around unconsidered, or invoked in ways that hold more content than they should.

Meanwhile, throughout the 20th century, evangelical Christians became a marginalized and culturally alienated sector of American society–war-fodder, factory labor, debt serfs, and a radically pro-military and pro-business voting bloc. Views spread with migrations to Southern California, the foundation of the John Birch Society, the new political alliance between the Deep South and Greater Appalachia, and uneasy relations between black and white Baptist activism. Segments became militarized or paramilitarized by the 1930s and folded into various (and often rebellious) aspects of imperial policy by the 1970s. By the 1970s, fierce anti-evolutionary rhetoric, although practically devoid of content or even relevance, became infused with the force of anti-communism and patriotism, as well as real money from televangelism and church-centered community organizing and was now feared and courted as a genuine political force. The language of anti-establishment defiance has become patriotic, while retaining complete rejection of evolution as an atheist and immoral creed.

The content of evolutionary theory and even anything resembling theology are now completely out of the picture, providing only cherry-picked catch-phrases. These rhetorical battles over how to use the terms “evolution,” “Darwinism,” and “natural selection” are embedded semiotics for specific and concrete policy battles, and policies concerning whose kids get educated by whom. This is a classic example of religion providing the rhetoric and organizing mechanisms (including community identification) for a policy issue. There’s no need for “belief” or “faith” to be brought into the discussion at all.

The real issue at hand is the refusal to look at the human animal–the contention that is kept most silent of all. Both mainstream “tamed” evolution and radical/rural Christian activism deny talking bluntly about humans, such that the last time anyone really did so was Thomas Huxley’s Evolution and Ethics in the early 1890s. This doesn’t go back to Charles Darwin in 1859; it goes back to Linnaeus putting humans right into the Systema Naturae in 1740, smack into the primates, long before “evolution” was a glint in Erasmus Darwin’s eye. Whether it was the Anglican Church having a hairy cow over Lawrence or Chambers or Essays and Reviews, or the distortions into social progressivism or imperial profiteering, or the later appropriation-for-an-enemy by the Populist organizers, that’s the crux, the draw–the puncher: humans being animals. Mainstream and marginalized/radical alike, whether they claim to embrace evolution or claim to combat and defy it (with even less), they never address the questions that Linnaeus, La Mettrie, Lawrence, Darwin, and Huxley almost uniquely brought into the light.

If you mix it up in these policy battles, don’t overlook the fact that you’re acceding the framework of the argument to your opponent–and keep ourselves as humans in the closet.

A version of this article originally appeared on author Ronald Edward’s blog.

Featured image credit: Six editions of On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin by Wellcome Images. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The evolution of evolution appeared first on OUPblog.

10 facts about the “king of instruments”

The organ is a complex, powerful instrument. Its history is involved and wide-ranging, and throughout the years it has commanded respect as it leaves its listeners in awe. To celebrate the organ, we compiled a list of 10 facts you may or may not know about this magnificent instrument:

Mozart once famously praised the organ, writing, “in my eyes and ears… the king of instruments.”

There are three main parts to the construction of an organ: the wind-raising device, the windchest (also called soundboard) with its pipes, and the (keyboard and valve) mechanism admitting wind to the pipes.

The organ is one of the most complex of all mechanical instruments developed before the Industrial Revolution.

The cinema organ, or theater organ, is a type of pipe organ built between 1911 and 1940 specifically for the accompaniment of silent films and the performance of popular music. It can be differentiated from those of traditional design by the use of a strongly fluctuating wind supply which caused the pipes to speak with an exaggerated vibrato. Cinema organs were provided with numerous percussion stops such as drums, cymbals, and xylophones, as well as such various sound effects (‘traps’) as bird chirping, police sirens, train whistles, ocean waves, and crashing sounds.

The colour organ is an instrument designed to relate the aural sensation of music to the visual sensation of colour. The first known attempt to build a colour organ was by the Jesuit Louis-Bertrand Castel, whose clavecin pour les yeux, proposed as early as 1725, had 60 coloured, illuminated glass panes mounted in a frame over a harpsichord, each pane covered by a shade that opened when a key was pressed.

Organ console of the Convention Hall in Atlantic City (New Jersey). CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Organ console of the Convention Hall in Atlantic City (New Jersey). CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.An organ is the emblem of St Cecilia, patron saint of music.

There are several classes of organ pipes, the two oldest and most integral to the development of the organ being flue pipes and reed pipes. More common, though not necessarily more varied, are flue pipes. Both types operate on the coupled-air system of sound production common to flutes, recorders, oboes, clarinets, etc.

The earliest, simplest organs consisted of one set of pipes, each pipe corresponding to one key of the keyboard. Beginning in the 15th century organs could include many sets of pipes of different pitches and tone-colors, and multiple keyboards. Modern organs are found in all sizes, from one-manual instruments with two or three sets of pipes, to ones with four or more manuals and several thousand pipes.

The first organs in the Americas were brought from Spain to Central America by Franciscan and Dominican missionaries in the mid-16th century. During the 17th century the use of organs—both imported and locally built—was widespread throughout Spanish colonial America; 17 small organs are reported as being in use in 1630 in what is now New Mexico, and one is later recorded in present-day Florida.

The invention of the organ is attributed to Ctesibius of Alexandria in about 300 BCE. His hydraulis had the basic elements that define an organ: a row of pipes, one for each note, with a key for each to admit the air, which was supplied by bellows.

Headline image credit: Davis Concert Organ. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 10 facts about the “king of instruments” appeared first on OUPblog.

The UK Competition Regime and the CMA

On 5 February 2015, the National Audit Office (NAO) published a report entitled ‘The UK Competition Regime’. The report assesses the performance of the UK competition regulators, focusing on the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). It concludes that the CMA has inherited certain strengths, including a positive legacy of merger and market investigation work. However, it has also inherited problems in competition enforcement, which derive, according to the NAO, from a difficult legal environment, very low business awareness of the organisation and competition law more broadly, and reputational damage caused by a series of high profile losses in court.

The NAO report notes that businesses’ awareness of the CMA and competition law is low, which may harm compliance. According to the CMA’s 2014 survey of UK industry, less than 2% of businesses knew the CMA well or very well. Although only recently formed at the time of the survey, the CMA compared very unfavourably to the Financial Conduct Authority, which had only been created in 2013. In terms of competition law, only 23% of businesses felt they knew competition law well, while 20% had never heard of it at all and a further 25% did not feel they knew it well.

These statistics are fairly surprising. Clearly the CMA has a lot to do to increase awareness about competition law. Their current agenda indicates that this is an important priority for the CMA.

The NAO concludes that, using the current statistics, it is difficult to effectively capture the impact of the CMA’s work and its individual tools. In particular, it is unclear whether market investigation references which the CMA has been focusing on provide real value to markets and consumers. It is suggested that for these reasons it is difficult for the CMA to set its priorities. The NAO also notes that the CMA is hampered in its choice of tools and processes due to the legal criteria which affect its decision making, and recommends that the CMA does more work in calculating the impact of its work. The Report states that the Government should regularly report the full cost of the competition regime and keep its cost-effectiveness under review. In addition, the NAO recommends that the Government should develop indicators of the competitiveness of the markets, such as their profitability and the cost of entry and exit into the market.

In terms of competition law, only 23% of businesses felt they knew competition law well, while 20% had never heard of it at all

The Report notes that the CMA has improved the robustness of its investigation procedures, and that it has been successful in 15 of its last 19 civil court cases. However, the competition regime faces big challenges in increasing the number of enforcement decisions to date. Since 2012, the CMA has made on average four infringement decisions per year (16 in total). By contrast, in 2013 alone, the German competition authorities made 36 infringement decisions and their French counterparts made 23. This is replicated in the volume of fines levied. Between 2012 and 2014 the Office of Fair Trading and the CMA levied £65m of fines compared to almost £1.4bn in Germany. The NAO notes that there is a view among some stakeholders that because the UK is the best jurisdiction in which to contest an adverse finding, and because the CMA is more focussed on market studies and market investigation references, the CMA is reluctant to take enforcement action.

The CMA responded positively to the report and said it demonstrates that the CMA “has made significant progress in improving how the competition regime works”. However, it recognised that there is still more to be done in terms of increasing the number and speed of competition enforcement cases. It remains to be seen whether the increased case flow which the NAO has noted in its Report is a sign of things to come and whether it will result in an increased number of enforcement decisions.

In response to the worrying numbers relating to lack of competition law awareness, the CMA said it is delivering a multi-sector compliance programme to raise awareness amongst small and medium sized enterprises of competition law and the CMA’s role in enforcing it. If successfully rolled out, this training could have an impact on awareness within businesses, which in turn should have an impact on competition law compliance. Ultimately, however, some high profile, successful enforcement cases would go a long way to increasing awareness of and compliance with competition law.

Featured image credit: Panorama of the City of London from Michael Cliffe House by Alexander Kachkaev. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The UK Competition Regime and the CMA appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers