Oxford University Press's Blog, page 521

April 16, 2016

Five random facts about Shakespeare today

Certain facts surrounding Shakespeare, his work, and Elizabethan England have been easy to establish. But there is a wealth of Shakespeare knowledge only gained centuries after his time, across the globe, and far beyond the Anglophone realm. For example, new textual analysis has pointed to collaborations with other playwrights, while other evidence — that he may have smoked marijuana — may be less reliable (and point to some current preoccupations). Here’s a brief look at what distinguishes the Bard of the early 21st century to the one we knew before in five random facts.

Othello, a tragedy, may have been originally intended as a comedy. Researchers at the Folger Shakespeare Library used data-mining techniques to analyze the vocabulary and syntax of the First Folio. Their software analysis revealed that it is, linguistically, a comedy.

Up to 90,000 schoolchildren have participated in free, live Shakespeare “Schools’ Broadcasts” organized by the Royal Shakespeare Company. The broadcasts are free to all UK students and are accompanied by other interactive resources and activities. The next production will be The Merchant of Venice and it will be broadcast on 21 April 2016.

Over the past fifteen years, scholars have explored the idea of Shakespeare as a businessman as opposed to a Romantic artist in more depth. Bart Van Es (Shakespeare in Company) argues that Shakespeare’s role as both investor and playhouse shareholder shaped the production of his art.

Shakespeare is the most significant British cultural icon, according to international survey results released in a larger piece for the British Council in 2014. The survey was conducted on 5,000 young adults in India Brazil, Germany, China, and the United States, who were asked to name an individual they associate most with UK arts and culture. Queen Elizabeth and David Beckham were a close second and third, respectively.

Alexander Shurbanov’s translations of Hamlet (2006), Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth (2012) into the Bulgarian language are the latest academically and theatrically reliable versions. Translations of Shakespeare’s work into Bulgarian began in the 19th century, with the earliest versions of Julius Caesar and Cymbeline published in 1881. During and since the 1990s, multiple translations of his plays and sonnets have flourished, thus completing the Bulgarian canon.

Featured Image: “Statue of William Shakespeare at the centre of Leicester Square Gardens, London” by Elliott Brown. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

The post Five random facts about Shakespeare today appeared first on OUPblog.

Lost in the museum

You go to the museum. Stand in line for half an hour. Pay 20 bucks. And then, you’re there, looking at the exhibited artworks, but you get nothing out of it. You try hard. You read the little annoying labels next to the artworks. Even get the audio-guide. Still nothing. What do you do?

Maybe you’re just not into this specific artist. Or maybe you’re not that into paintings in general. Or art. But on other occasions you did enjoy looking at art. And even looking at paintings by this very artist. Maybe even the very same ones. Just today, for some reason, it’s not happening. Again, what do you do?

What I just described happens to us all the time. Maybe not in the museum, but in the concert hall or when trying to read a novel before going to sleep. Engagement with art is a fickle thing – it can go wrong easily. And if aesthetics as a discipline is a meaningful enterprise, it should really try to help us to make sense of situations like this.

Much of the standard apparatus of aesthetics will be hopelessly irrelevant here. The ontology of artwork is a fascinating topic, but how is that going to help you try to enjoy the exhibition you just paid a lot of money for? The same goes for other standard topics in aesthetics, like the relation between art and morality or the concept of beauty.

I don’t think the purpose of aesthetics is to provide self-help for troubled museum-goers. But the enjoyment of artworks can be a bumpy ride and aesthetics should say something about this process, how it can go wrong and how it can be immensely rewarding. And how the line between the two can be very thin.

Here I want to bring in the concept of attention. Depending on what you are attending to, your experience will be very different. A simple demonstration of this is the famous gorilla experiment about inattentional blindness: what you’re attending to has serious consequences for whether you spot a man in a gorilla costume dance in the middle of the screen.

Here is a more artsy example. Look at this landscape painting:

Landscape with the ‘Fall of Icarus’ by Pieter Bruegel de Oude (1526/1530 – 1569). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Landscape with the ‘Fall of Icarus’ by Pieter Bruegel de Oude (1526/1530 – 1569). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.You may or may not identify this as a 16th century Flemish landscape painting by Bruegel. In fact, half landscape, half seascape. It’s also, a nice diagonal composition, with the peasant at the centre. Now you read the title: The Fall of Icarus.

What? Where is Icarus? I don’t see anyone falling? Where? You feverishly scan the picture for some trace of Icarus and then you find him (or at least his legs): just below the large ship. Now look at the picture again, with this in mind.

My guess is that your experience is now very different. While the part of the canvas where Icarus’s legs are depicted was not a particularly salient feature of your experience of the picture before (perhaps you didn’t even notice it), now everything else in the picture seems to be somehow connected to it.

Attending to this feature can make an aesthetic difference: it can change your experience in an aesthetically significant way. Maybe you experienced the picture as disorganized before and attending to Icarus’s legs pulls the picture together. I’m introducing the jargon of ‘aesthetically relevant properties’ for properties (like Icarus’s legs) that are such that attending to them makes an aesthetic difference (whatever is meant by ‘aesthetic difference’).

Aesthetically relevant properties are very different from ‘aesthetic properties’ (like being beautiful or being balanced or being graceful); this concept that has dominated aesthetics and the philosophy of art in recent decades. A lot has been said about aesthetic properties. My point is that we should talk at least as much about aesthetically relevant properties – not deep and venerable concepts like beauty, but simple features like Icarus’s legs.

So we’ve got some jargon, some emphasis on attention, but how is this going to help us in the museum? The short answer is that if attending can influence our experience in general, it can also influence our experience of artworks. Attending to the irrelevant features of the artwork can seriously derail your experience.

How about the other way round? Does attending to the ‘right’ features guarantee a rewarding and meaningful, ‘aesthetic’ experience? If only! I’m not even sure that there are ‘right’ features of artworks, but a reasonable thing to do when you’re just not getting the artwork you’ve been staring at is to move your attention around – attend to various, thus far unexplored features of it. Let me give an example.

I look at this picture a lot – it’s in a museum that is just across the street from where I live:

The Annunciation, predella panel from the St. Lucy Altarpiece by Domenico Veneziano (1442-1445). Public domain via WikiArt.

The Annunciation, predella panel from the St. Lucy Altarpiece by Domenico Veneziano (1442-1445). Public domain via WikiArt.And while I have had strong and rewarding experiences (maybe even ‘frissons’) in front of it, this does not happen every day. Just yesterday, I went there knowing that I’ll have to spend the afternoon writing a difficult letter of recommendation and that somehow distracted me so much that I couldn’t enjoy it at all.

But here is something to try. The painter (Domenico Veneziano) had a little fun with the axes of symmetry: the symmetrical building is offcentre – it’s pushed to the left of the middle of the picture. And the ‘action’ is also off-centre – but it is pushed to the right, not to the left. Attending to the interplay between these three axes of symmetry (of the building, of the picture itself and of the axis halfway between Mary and the archangel) can make a huge aesthetic difference.

Now, does attending to this interplay of the axes of symmetry guarantee that you have an aesthetically rewarding experience? Alas, not. It didn’t work yesterday, for example. But it often does work. Also, attending to this ‘aesthetically relevant property’ may not work for everyone – but it may work for some. What art critics (and audio-guides) should do is to point out aesthetically relevant properties. Pointing out aesthetic properties like being graceful is not so helpful. Talking about which part of Italy the painter was born is not so helpful either. But pointing out an aesthetically relevant property can transform one’s experience from one moment to another.

In the museum, and also outside, it is worth paying attention to what we are attending.

Featured image credit: ‘The statement’, by Paulo Valdivieso. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Lost in the museum appeared first on OUPblog.

April 15, 2016

Summer school for oral historians

Both in the archives and out in the field, we’re pleased to highlight some of the important work that oral historians undertake. Last month Sarah Gould shared some of her experiences and questions about using oral history in a museum exhibit. Earlier this year, we talked to audio transcriptionist Teresa Bergen, who helped us see another side of the oral history process. This week, we hear from Shanna Farrell about UC Berkeley’s Advanced Oral History Summer Institute, and how former students are building on their experiences in the program. Summer training programs now exist in multiple places, and we’re excited about the possibilities they have for bringing even more people into the world of oral history.

When I joined UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center (OHC) in late 2013, I quickly began work designing, planning, and running the Advanced Oral History Summer Institute (SI), which is organized around the life cycle of the interview. Because leading the SI is one of my most important roles at the OHC, it’s hard for me to be objective about its value (I think our week is a robust resource and provides excellent formal training). While it’s easy for me to discuss the importance of seminars and workshops I took in graduate school, this is a tricky task now that I’m on the other side of educational programming. So, I decided to turn to two SI alums for their perspectives on our week-long institute. I spoke with Dan Royles, an Assistant Professor of History at Florida International University in Miami, Florida, and Antonella Vitale, a PhD candidate in the Department of History at the City University of New York in Manhattan.

Dan Royles was a PhD candidate at Temple University when he attended the SI in 2011. He was studying African-American AIDS activism and wanted oral history to play a big role in his research. He had completed a few informal interviews and a day-long workshop on oral history at Temple, but was hoping to learn more about the OHC’s methodology and process so that he could take a more considered approach to archiving. “The highlight of the Summer Institute was learning how to analyze and integrate oral sources into my work, and exploring critical issues of narrative and orality,” he says. He also cites interview practice, panels on the multiple aspects of interviews, and discussion sections as helpful in becoming more comfortable in interview settings. After the SI, he completed interviews with about thirty-five people and defended his dissertation in October 2015.

Antonella Vitale came to the SI in 2014 hoping to learn similar aspects of oral history. “At the time, I was planning on doing oral histories for my dissertation project,” she says. “I had never had any oral history training. I had read practical techniques, some books on oral history, and oral history theory, but I was really excited when I saw that [the OHC] was doing a Summer Institute so that I could learn more and become more comfortable.”

Vitale’s work explores the practice of fuitina in Sicily, Italy, which is a type of rape marriage. “A man can kidnap a women and raping her, with the purpose of marrying her. It’s also a practice in which young couples escape to marry and force their families to accept them being together. Often, families are against partnerships for various reasons. It’s got an ugly, but romantic side. This practice has never been explored in historical scholarship and my work seeks to define it and understand how it manifests in society and juxtapose it with meta-narratives that exist about it popular culture,” Vitale explains.

She says that the week allowed her to formulate better questions and hone the scope of her interviews. “The SI helped to reinforce the way in which people present themselves and tell their stories. It also gave me the confidence to push people a little harder and not back down when they were trying to brush off a question,” she says. She conducted twenty-eight interviews in Italy during the summer of 2015 and is now writing several chapters of her dissertation, which she hopes to defend next year.

Royles and Vitale had something else in common: they both now use oral history in their classroom. Royles teaches a graduate course dedicated to its practice and theory, and Vitale uses oral history in a semester-long interview project for her undergraduates. “The last few semesters I had the students pick a person to interview as their culminating project,” she says. “Throughout the semester I have various workshops on picking a subject, thinking of topics to explore, and how to do the pre-interview. A lot of the things that you taught us I’m teaching my students. We do a workshop on developing interview questions, bring in photos and do practice interviews, and work on outlines. They go off and do the interviews, transcribe them, and then we develop a narrative based on the transcript. They do peer reviews and a five-minute presentation. That’s been really fun and the students really love it as a project, as opposed to writing a research paper.”

Moreover, Royles said that having formal training in oral history gave him a competitive advantage when he was on the job market last year. It gave him traction, and his emphasis on this work, coupled with the passion that he developed for interviewing, helped him get three teaching offers when the market was the toughest it has been in years. He ultimately landed a tenure track faculty position.

It’s encouraging to hear that not only are scholars seeing the value in incorporating oral history into their work, but both they and their home institutions understand the importance of formal training.

For more, check out Dan Royles’ work on African American AIDS Activism Oral History Project, the project’s Omeka site, his work indexing interviews for the Staring Out to Sea oral history project, and his forthcoming article on teaching with OHMS in the Oral History Review. The Oral History Summer Institute is a one-week seminar on the methodology, theory, and practice of oral history. It will take place on the UC Berkeley campus from 15-19 August 2016. For more information about the institute, or to submit an application, visit them online. Chime into the discussion in the comments below, or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

Featured image: UC Berkeley. Photo by Charlie Nguyen. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Summer school for oral historians appeared first on OUPblog.

Randomized controlled trials: Read the “fine print”!

Most randomized controlled trials (RCTs) can appear deceptively simple. Study subjects are randomized to experimental therapy or placebo—simple as that. However, this apparent simplicity can mask how important subtle aspects of study design—from patient selection to selected outcomes to trial execution—can sometimes dramatically affect conclusions. Given how much influence large RCTs can have in medical practice, it is important for doctors to be familiar with the “fine print” of how the landmark studies in their specialties are conducted.

In neurology, one of the most prominent case studies of the impact of RCT “fine print” is the story of endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke patients. Ischemic stroke involving clots within the large vessels of the brain can be absolutely devastating for patients with regards to their ability to walk, talk, think, and eat. When experimental catheter-based procedures began emerging over the past two decades that made possible the direct removal or lysis of large vessel occlusions (with what appeared to be acceptable rates of complications), a controversy developed within the stroke community. How could quickly removing a clot with a relatively safe catheter ever be the wrong thing do to? Why even subject such patients to a randomized trial, especially if insurance companies seem willing to pay for the procedure to be done?

With this mentality, the stroke community struggled for years with enrollment of severe ischemic stroke patients into formal RCTs of endovascular therapy. Surprisingly, the pendulum of medical opinion swung wildly in 2013, when the New England Journal of Medicine published three large RCTs of endovascular therapy that were actually unable to prove any benefit of such catheter-based procedures for improving patient recovery from large-vessel strokes. The sheer scope of the three well-publicized, simultaneous studies was enough to reverse the question many doctors were asking in these situations from, “How could we possibly consider enrolling an endovascular candidate in a randomized clinical trial?” to “How can we even bring stroke patients to the endovascular suite, with three negative trials?”

However, as the stroke community became more familiar with the “fine print” of the three 2013 trials, it became clear that many of these details were absolutely critical in unpacking the trials’ negative results. The International Management of Stroke III Trial (IMS III), one of these three landmark trials, has now been dissected perhaps as much as any stroke trial in history. On the surface, the trial design seemed straightforward: 58 centers randomized patients who (1) presented early with severe stroke symptoms and (2) had already received intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (IV t-PA, an IV clot-busting agent, the accepted standard of care for acute stroke) to either endovascular therapy or conservative management. IMS III was stopped early for futility and found no difference between groups in terms of patients who were functionally independent at 90 days. Simple as that?

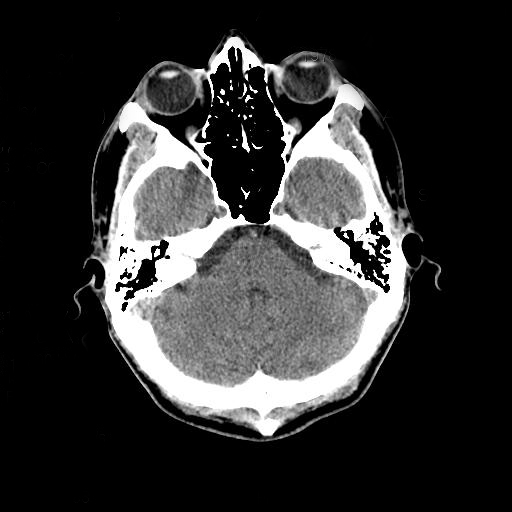

Image Credit: CT scan of a normal human brain by Andrew Ciscel. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: CT scan of a normal human brain by Andrew Ciscel. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The “fine print”: Less than half of the patients enrolled in IMS III underwent a CT angiogram prior to IV t-PA. A CT angiogram is the best test for non-invasively identifying a large vessel occlusion for an acute stroke patient, and thus it is possible that a large number of patients enrolled in the study didn’t have a large-vessel clot to remove. A substantial proportion of patients enrolled in IMS III already had evidence of significant stroke on the initial head CT scan, meaning that much of their brain had already suffered irreversible damage before they were even potentially randomized to a clot retrieval. Many patients who were good candidates for the study were likely kept out of the study by doctors who were uncomfortable with not guaranteeing endovascular therapy for them, a bias that could have disproportionately left poorer endovascular candidates as the patients who were randomized. The length of the IMS III trial resulted in the fact that, by the time the trial was completed, the technologies that it studied were essentially out of date and replaced by catheters that had a much higher success rate of clot removal.

These limitations of the IMS III trial and the other two negative trials published in 2013 ultimately paved the way for the current era of stroke treatment. A series of RCTs published in the past two years have since shown overwhelming clinical benefit for endovascular therapy in large vessel stroke—provided that patients are shown to have actual large vessel clots before the procedures, that their initial irreversible stroke burden is small, and that patients undergo procedures using cutting-edge catheter technology. Although it was a “failed” trial, IMS III has a large legacy in stroke and in neurology—simple aspects of study design of execution can make all the difference in your RCT results. It’s important for all clinicians to read the “fine print”!

Featured image credit: Bethesda Naval Medical Center by tpsdave. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Randomized controlled trials: Read the “fine print”! appeared first on OUPblog.

Rising to the challenge: innovations in child protective services

Protecting children from maltreatment is one of the most challenging responsibilities in social and health services. Most CPS investigations and resulting service delivery are helpful to children and families and occur without incident. However, the public at large is correctly concerned about the welfare of children living in potentially unsafe situations. Public dissatisfaction with services that are intended to assure children’s safety arise from many sources, including, most notably, the idea that it is possible to predict and prevent all child abuse or even all child deaths. Agencies do work to identify probabilities of future harm, but science has not progressed to the point that it is possible predict violence that will result in injury or fatal neglect. Gonzalez and colleagues provide one example of this problem with respect to physical abuse. Given this challenge by the public, agencies are left to struggle with often antiquated systems, minimal levels of staffing, and insufficient supports, in the context of a highly politicized environment. It is no wonder that there are many difficulties in fulfilling the mandate to protect children.

This unhappy state of child protective services need not be inevitable. There are pockets of excellent practice that represent some of the best service delivery possible in this difficult environment. Two counties often recognized for their excellence include Carver and Olmsted Counties in Minnesota. These counties are not without challenges but staff rise to meet them in a planful way, taking control of their own training, practice, and caseload management in their own unique fashion. While both counties employ well-known methods of decision making and practice, such as Structured Decision Making® and Signs of Safety®, they do so quite differently and add other models such as solution focused treatment resulting in their own unique county-specific approaches to practice. A history of their innovation and development over time is described by Wilder Research.

Higher quality child protective services not only protect more children more effectively, they also save money by keeping children from being unnecessarily placed out of their homes. For those children who are able to remain at home or with extended family, the trauma of placement, ensuing difficulties in school, or even with the law, can be avoided. In the U.S., Dr. Becky Antle’s studies on Solution Based Casework practice in child protection suggest good practice will lessen unnecessary placements and at the same time increase protection of those children who are at serious risk of harm.

The question is how to ensure that good practice is widely adopted and maintained over time. In reviewing practice at different high-functioning sites, it appears there are commonalities such as connecting with the family, focusing on the immediate problem, and supporting the workers in ongoing training, but there are many differences in how these practices are organized and supported, due to funding structures and local organization of services. There are many efforts to help support quality, such as the 2011 Child and Family Services Improvements and Innovations Act which made the use of federal funding more flexible, the work of the U. S. Children’s Bureau and research groups such as the National Implementation Research Network, but the many facets of practice, management, and local needs vigorously militate against innovation and change.

Discussions with those initiating the most successful changes yield common themes with respect to maintaining common goals, supporting and respecting workers, and constantly changing to meet new problems and demands. They recognize that the need to innovate is not a one-time occurrence; it is a constant never-ending way of life in complex organizations. In a recent study of innovation in child welfare services conducted by the Centre for the Study of Services to Children and Families in British Columbia and Minnesota, innovation as an enduring commitment, rather than a discrete occurrence, was thematic in conversations with child welfare the most successful leaders.

While a good deal of work has been done to guide agencies in adopting innovative practices, one of the most relevant developments in leading innovation comes out of the business community. Reporting on hundreds of hours of conversation with leaders and workers from diverse companies, Hill et al. cite Coughran of Google, saying “the role of a leader of innovation is not to set a vision and motivate others to follow it. It’s to create a community that is willing and able to generate new ideas.” According to Hill and colleagues, it occurs when teams have shared values, rules of engagement that focus on the quality of discourse, and supporting problem solving through encouraging debate, quickly testing and evaluating new ideas, and entertaining solutions that may combine disparate or seemingly opposed ideas. Establishing esprit de corps, encouraging debate about the optimal ways to achieve desired ends, and supporting some degree of trial and error in program design in governmental agencies is counter-intuitive and can be politically risky. Nevertheless, a firm commitment to supporting the development of such a creative agency appears to be the first step in supporting high quality practice. By establishing common goals for the entire team and agency, investing in workers and staff, supporting them in their work, and treating them as creative colleagues, collective genius, the ability of an organization to rise to challenges through collective effort and creative problem solving may indeed flourish.

Featured image credit: By Maxim Matveev, Public Domain via Pexels

The post Rising to the challenge: innovations in child protective services appeared first on OUPblog.

The invention of the information revolution

The idea that the US economy runs on information is so self-evident and commonly accepted today that it barely merits comment. There was an information revolution. America “stopped making stuff.” Computers changed everything. Everyone knows these things, because of an incessant stream of reinforcement from liberal intellectuals, corporate advertisers, and policymakers who take for granted that the US economy shifted toward an “knowledge-based” economy in the late twentieth century.

Indeed, the idea of the information revolution has gone beyond cliché to become something like conventional wisdom, or even a natural feature of the universe like the freezing point of water or the incalculable value of π. Yet this notion has a history of its own, rooted in a concerted effort by high-tech companies in the 1960s to inoculate the American public against fears that computing and automation would lead to widespread job loss. The information revolution did not spring from the skull of Athena or emerge organically from the mysterious workings of the economy. It was invented.

Let’s go back to the 1950s. A young journalist named Daniel Bell was working for Fortune magazine, at a time when magazines for rich people actually employed thoughtful, perceptive social critics. He was one of several observers who began to notice that a fundamental shift was sweeping the United States; its industrial base, the “arsenal of democracy” that won World War II against fascism, was shrinking relative to other sectors of the economy, at least as a portion of employment. Around the same time, economist Colin Clark hypothesized that there were different sectors of the economy: primary (meaning agricultural and extractive industries), secondary (manufacturing) and tertiary (everything else). Other economists came along and refined the concept to distinguish between different types of “services,” but it was clear that greater productivity in industry—gained from automating the process of production and, eventually, offshoring work to take advantage of cheaper labor in the developing world—meant that an increasing proportion of Americans worked in fields such as retail, healthcare, and education, relative to the manufacturing sector that had so defined the US economy in the early to mid-twentieth century.

Image credit: Student with vintage IBM computer. Technology by Brigham Young University – Idaho, David O McKay Library, Digital Asset Management. Public Domain via Digital Public Library of America

Image credit: Student with vintage IBM computer. Technology by Brigham Young University – Idaho, David O McKay Library, Digital Asset Management. Public Domain via Digital Public Library of AmericaIt was not just intellectuals such as Bell or Clark who realized this change was underway. The young radicals of the New Left recognized that the economy was undergoing a fundamental transformation, as pointed out in the seminal Port Huron Statement of 1962. The generation that was coming up in the universities realized that they would be taking charge of American life in offices and laboratories, as the real number of manufacturing workers had held steady relative to the growth of the rest of the economy since the late 1950s. They worried about a “remote control economy,” where workers and the unions that represented them were relatively diminished, and an incipient class of knowledge workers—a term that would not really gain currency until the 1970s—would hold a new sort of hegemonic power. In many ways, the New Left was the political expression of this class in its infancy.

But a new, postindustrial economy could have taken any number of forms. In fact, many commentators in the 1960s assumed that increasing automation would result in greater leisure and shorter working hours, since we could make more stuff with lesser work. It remained for high-tech firms such as IBM and RCA to set the terms for the way we understood the changing economy, and they did so with gusto. With the help of canny admen such as Marion Harper—who intoned in 1961, “to manage the future is to manage information”—they rolled out a public relations campaign that celebrated the “information revolution.” Computers would not kill jobs—they would create jobs. Computers would not result in a cold, impersonal, invasive new world, empowering governments and corporations at the expense of the little guy—they would make life more efficient and convenient.

Fears of technological unemployment were very real during the 1950s and 1960s. Few recall that unemployment rates in parts of the United States were as high as ten percent in the late 1950s, and Congressmen held hearings over the issue of jobs being displaced by new technology. At the same time, government—from the Post Office to the Pentagon—was the biggest buyer of computer technology by a wide margin. IBM needed government, and the US Census needed IBM to crunch its numbers. Hence, tech companies yearned to manage public opinion, and they enlisted the help of intellectuals such as media theorist Marshall McLuhan and anthropologist Margaret Mead to assuage anxieties about the implications of new technology. The latter contributed to a huge ad supplement taken out by the computer industry in the New York Times in 1965 called “The Information Revolution,” joining notables such as Secretary of Labor Willard Wirtz in an effort to explain that automation was not the enemy. IBM’s competitor RCA set up a major public exhibition in Manhattan’s Rockefeller Center in 1967 with the same theme.

In other words, the very concept of an “information revolution” was introduced and explicitly promoted by powerful tech firms at a time when Americans were worried about their jobs and new technology. Like Don Draper’s famous toasted tobacco, it came from Madison Avenue. They lent shape and direction to inchoate and confusing shift in the political economy of the United States, by dint of shrewd marketing. However, we might have interpreted things differently. The future, as seen from the 1960s, might not have depended on the prerogatives of Silicon Valley, Hollywood, and other progenitors of intellectual property, but we have by and large been convinced that the fate of the nation lies in the hands of scientists, screenwriters, engineers, and all the other people who make the coin of the realm: information. It is worth considering, though, that America once had to be persuaded to believe that information was the inevitable future toward which we are all inexorably heading. As left activists are fond of saying, another world is possible—and once was.

Featured image credit: ‘The Hypertext Editing System (HES) console in use at Brown University, circa October 1969 by Greg Lloyd’ by McZusatz. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The invention of the information revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

Looking for information: How to focus on quality, not quantity

Solving complex problems requires, among other things, gathering information, interpreting it, and drawing conclusions. Doing so, it is easy to tend to operate on the assumption that the more information, the better. However, we would be better advised to favor quality over quantity, leaving out peripheral information to focus on the critical one.

Our approach to information should be straightforward; after all, it feels that any data related to the problem that we are trying to solve should be beneficial. But, in practice, this isn’t the case. More information is not necessarily better. In fact, gathering more data is time consuming; it may provide you with unwarranted confidence (Oskamp, 1965), (Son & Kornell, 2010), (Bastardi & Shafir, 1998); and it dilutes the diagnosticity of other information items (Arkes & Kajdasz, 2011). More information is not necessarily better.

Adopt a top-down approach to gathering information.

That is, for the bulk of your effort, once you have clarified the question that you want to answer (or the hypothesis that you want to test), identify which information you need to obtain to help you answer it. Only then should you look for that information, obtain it, and process it. This information should have a high diagnosticity; that is, the likelihood of observing it will be significantly different depending on whether the hypothesis is right or wrong. This is only advisable to an extent, because if you follow this approach blindly, you might not see important information that you might encounter by chance during your analysis. Therefore, you should retain some flexibility in your approach and embrace serendipity.

Transcend “that’s interesting” by understanding the “so what?” of each item of information.

“That’s interesting,” by itself, isn’t really flattering. Isn’t it what you replied the last time a friend asked you your opinion about that painting of theirs that you didn’t really like? In the context of problem solving, forcing you to understand why you think something is interesting (or not) and formulating it, ideally in writing, forces you to analyze it in depth and be accountable for your thinking.

Create an environment where important data sticks out.

If you have managed to follow some of the recent political “debates” for the primaries of the US presidential elections, you have seen firsthand how to create an environment that doesn’tsupport the exchange and analysis of ideas: talk over one another, call each other names, deflect the conversation toward peripheral or non-critical aspects.

Contrast this with how members of the Manhattan Project team were working (as related by Physics Nobel Laureate Richard Feynman (1997)) when deciding how they were going to separate uranium to extract the fissionable isotope:

In these discussions one man would make a point. Then [Arthur] Compton, for example, would explain a different point of view. He would say it should be this way, and he would be perfectly right. Another guy would say, well, maybe, but there’s this other possibility we have to consider against it.

I’m jumping! Compton should say it again! So everybody is disagreeing, all around the table. Finally, at the end, [Richard] Tolman, who’s the chairman, would say, “Well, having heard all these arguments, I guess it’s true that Compton’s argument is the best of all, and now we have to go ahead.”

It was such a shock to me to see that a committee of men could present a whole lot of ideas, each one thinking of a new facet, while remembering what the other fellow said, so that, at the end, the decision is made as to which idea was the best—summing it all up without having to say it three times. So that was a shock. These were very great men indeed.

Integrating these ideas, evidence gathering requires you to continuously oscillate between analyzing minute aspects of your problem and stepping back to understand their implications on the big picture. That latter part can easily be lost in the details after weeks or months of diving deep into one aspect of your problem. Yet it remains a critical component of successful problem-solving and deserves your continuous attention.

Featured image credit: Supernova SN2014J (NASA, Chandra, 08/22/14), from NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center via Flickr.

The post Looking for information: How to focus on quality, not quantity appeared first on OUPblog.

Britain and the EU: going nowhere fast

A couple of years ago, I was asked to write a piece for the OUPblog about the consequences of David Cameron’s Bloomberg speech, where he set out his plans for a referendum on British membership of the EU. I was rather dubious about such a vote even happening, and even more so about the quality of the debate that would ensue.

As much as I was wrong about the former, the latter has been more than borne out by events so far.

In the three years since Bloomberg, we have not seen the articulation of a deep and broad public debate in the UK about its relationship with the EU, not even in the ten months that have followed Cameron’s unexpected general election win. As much as there are individuals and organisations trying to inform what debate there is – ‘The UK in a Changing Europe’ programme is a good example – they remain exceptional.

So what, you might ask? We don’t have a profound public debate each time we hold a general election. If voters choose not to be interested, then that’s not their fault or problem.

The difference is that general elections come around on a regular basis: if things go awry, then they can be picked over and revisited down the line. However, the EU referendum represents a one-off event, with a very large potential to shape our lives, both individually and collectively. Clichéd though it sounds, it is a decision that benefits careful consideration.

Unfortunately, this is an uphill struggle. There has never been a moment in the UK’s post-war history where there was fundamental reassessment of its role in the world: even the Suez crisis’ effect in the 1950s was more about limits to global power than it was about strategizing about the local neighbourhood. Successive British governments have preferred let the EU tick along in the background, with occasional excursions to contest some issue that had become a problem.

The European Union building in Brussels. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The European Union building in Brussels. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The result is a somewhat perverse situation, wherein the case against state policy is made much more than the case for it. And as the current referendum is showing, to rely on the weight of the status quo is to run a clear risk of coming unstuck.

The campaign that will run until 23 June is a moment where this might be addressed. It is a time to get questions answered, to propose ways forward from the vote and to create something at least a bit closer to a constructive and targeted policy towards the EU.

However, this means we have to be clear about the difference between the referendum itself and a public debate. The former simply needs to be won, as far as campaigners on both sides are concerned and they will do what it takes to achieve this. The latter, by contrast, has to recognise that this referendum is only one part of a long-term relationship, where decisions have consequences and short-term costs and gains have to be set against their long-term opposites.

Put differently, ‘winning’ the EU referendum will solve nothing in of itself. What will matter is how the UK proceeds from that decision. And that’s something that can only be done if we have a sense of what we hope to achieve, as a country, and as a community.

Featured image credit: Europe, by Chickenonline. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Britain and the EU: going nowhere fast appeared first on OUPblog.

April 14, 2016

The legacy of ancient Greek politics, from Antigone to Xenophon

What do the pamphlets of the English Civil War, imperial theorists of the eighteenth century, Nazi schoolteachers, and a left-wing American artist have in common? Correct! They all see themselves as in dialogue with classical antiquity, drawing on the political thought of ancient Greek writers. Nor are they alone in this; the idea that Western thought is a series of “footnotes to Plato,” as Alfred Whitehead suggested in 1929, is a memorable formulation of the extensive role of ancient Greece within modernity. Further reflection, however, will show that the West does not have an unbroken connection with ancient Greece, as knowledge of both language and culture declined in the medieval period – even the great Renaissance scholars sometimes struggled to master their ancient Greek grammar and syntax. Once the West does recover a relationship to ancient Greece, is its own role confined to writing “footnotes” under the transcendent authority of Plato? Perhaps we can reconstruct more varied forms of intellectual engagement.

One thing to remember is that the political thought of ancient Greek was not itself monolithic. The democratic experiment of classical Athens, the idealistic militarism of Sparta, the innovative imperialism of Alexander – such plurality of political forms gave rise to a wealth of commentary that ranged across the ideological spectrum. Moreover, texts that are not only political but have other identities too, like Athenian history or tragedy, also involve sustained reflection on the organisation of society and the workings of power. So the political writings of ancient Greece are not confined to Plato, or to Plato and Aristotle, and they offer a range of political positions.

Conversely, Western thought does not simply accept the authority of Greek texts, despite the huge cultural clout that the classical world undoubtedly wielded during much of European history. Instead, we can see later writers using the classical past as a partner in dialogue, to be variously embraced, rejected, modified, and sometimes transformed out of all recognition. For instance, recent research has shown how Xenophon has been understood as forerunner of Romantic exploration, American militarism, and Nazi ideology. From the opposite perspective, an appeal to the classical past has often shaped and altered the discourses of modernity, calling its basic assumptions into question. The study of this complex kind of engagement is currently undertaken by scholars in classical reception and The Legacy of Greek Political Thought Network enables classicists, historians, and political theorists to learn from each other how the classical past has been debated, interrogated, and contested in post-classical political writings.

Xenophon in Thomas Stanley’s History of Philosophy (1655). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Xenophon in Thomas Stanley’s History of Philosophy (1655). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The Network is interested particularly in studying the political work of ancient Greek writers other than Plato and Aristotle, and we also want to move away from debates about democracy to investigate how ancient writers have been deployed to pursue many other arguments. Topics studied recently range from the seventeenth century to the twentieth, taking in republicanism, colonialism, pedagogy, Aesop and Antigone. Pamphlets from the English Civil War include reflections on Sparta as ideal democracy, which challenge our current understanding of Spartan politics and imperial theorists of both Britain and France focus on Athens as paradigm of imperial power and decline, with considerably less interest in the city’s democratic identity. German pedagogues in the 1930s drew on Xenophon for characterisations of political leadership that they applied to the autocratic politics and culture developing in their own society, while Aesop provided a way of figuring radical politics for Hugo Gellert, an artist in 1930s New York. New readings of Antigone, via political philosophy as well as drama, enable further consideration of the relations between classical reception and political thought. The current political context presents challenges both relatively familiar and wholly surprising, but we can expect a dialogue with antiquity to continue.

Image: Plato’s Symposium – Anselm Feuerbach. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The legacy of ancient Greek politics, from Antigone to Xenophon appeared first on OUPblog.

Ancient Greek and Egyptian interactions

“You Greeks are children.” That’s what an Egyptian priest is supposed to have said to a visiting Greek in the 6th century BC. And in a sense he was right. We think of Ancient Greece as, well, “ancient”, and it is now known to go back to Mycenaean culture of the second half of the 2nd millennium BC. But Egyptian civilisation is much earlier than that: in the mid 2nd millennium BC it was at its height (the “New Kingdom”), but its origins go right into the 3rd millennium BC or even earlier.

Egyptians and Greeks are known to have been in contact already in the 2nd millennium BC, though we don’t know much about it. The picture becomes clearer from about 600BC, when the sea-faring Greeks were frequent visitors to Egypt. Some of it was for trade (there was a Greek trading-base at Naucratis in Egypt from about this time), some of it was about military services, and some of it was probably just sightseeing. By the 5th– 4th centuries BC Greek intellectuals had a pretty good idea of Egyptian culture. They knew it was ancient (in fact they greatly overestimated how old it was), and they saw it as a source of knowledge and esoteric wisdom. Some of them believed that Egypt had influenced Greece in the distant past; for the historian Herodotus, Greek religion was mostly an Egyptian import.

Flash forward to the Hellenistic period (late 4th– 1st centuries BC), when, following the conquests of Alexander the Great, Egypt was taken over by a Greco-Macedonian dynasty based in the new city of Alexandria. These Greek pharaohs communicated in Greek and the country itself became increasingly bilingual and bicultural, a process that continued into the Roman period. The most vivid symbol of the new Greco-Egyptian culture that developed is the popularity of Egyptian religion, particularly the goddess Isis, who had worshippers all over the Mediterranean by the 1st century BC.

One big thing Egypt and Greece had in common was their passion for literature. Greek literature was comparatively young, attested from about 700BC (Homer, Hesiod), although the Greeks probably had oral literature much earlier that that. Egypt has one of the earliest attested literary traditions in the world, going right back to the 3rd millennium BC.

Image credit: British Museum Egypt by Einsamer Schütze. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: British Museum Egypt by Einsamer Schütze. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Once Greeks were settled in Egypt, they must have encountered Egyptian literature. There was no shortage of Egyptian literature being written and performed in this period, most of it in the later form of the Egyptian language called “Demotic” (which has a really difficult script). We wouldn’t know anything about this today, but luckily some of the papyrus-manuscripts have survived, or at least pieces of them have. Tremendous advances have been made in identifying and deciphering these in the last few decades, and for the first time we can begin to see what Egyptian literature was like in the Hellenistic and Roman periods.

Some of it can be described as a literature of resistance. For most of the 1st millennium BC Egypt had been under the control of foreign powers, not just the Greeks, but the Persians in the 5th century and before them the Assyrians, and the popular literature imagines a world in which Egypt once had the upper hand, or will have again. A typical subject in Egyptian literature are the adventures of Egyptian pharaohs and other heroes battling against occupying enemies. A whole cycle of these stories centred around the pharaoh Inaros and his sons and their conflict with the Assyrians. Another national hero was the pharaoh Sesostris who was supposed to have once established an Egyptian empire larger than that of the Persians. There were also prophecies predicting a time in the future when the foreign occupiers would be gone. Besides this, there is also a lot of religious literature: for example, the so-called Story of Tefnut narrates how an angry goddess who has abandoned Egypt has to be persuaded to return; and the recently discovered Book of Thoth consists of esoteric writings related to priestly initiation.

We know the Greeks knew this literature because some of it was translated into ancient Greek (the Story of Tefnut, for example). In other cases, an Egyptian work or genre may have been adapted by Greek writers; for example, the “Book of Thoth” could have been a model for the Greek mystical literature known as the Hermetica, i.e the works associated with the god Hermes, the Thrice Great (Thoth and Hermes were always regarded as equivalents). This process could also have happened in the opposite direction, with the Egyptian texts being influenced by Greek models. For example, some of the narratives associated with Inaros may have been somehow influenced by the epic poems of Homer. Mutual influence of this sort probably happened mostly in Hellenistic and Roman periods, but it is likely that already in the 5th century BC, Greeks such as Herodotus, were encountering Egyptian literary traditions, albeit in oral form.

Headline image credit: Philae Temple HDR by Naguibco. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Ancient Greek and Egyptian interactions appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers