Oxford University Press's Blog, page 523

April 12, 2016

Bittersweet melodies of Agustín Lara in Güeros

The story of four teenagers on a quest to locate their ailing musical idol requires a mix of nostalgia, myth, apathy, and disillusionment. Played out across the vast urban expanse that is the City of Mexico, Güeros is conceived in the alternative deadpan style of Jim Jarmusch’s early films or, perhaps, Wim Wenders’ mid-1970s road movie triology. Director Alonzo Ruizpalacios chose a self-consciously cosmopolitan yet at the same time distinctly Mexican sound to convey the journey — the songs of Agustín Lara (1897-1970). For the Spanish-speaking world, Lara’s music tends to inspire feelings of melancholic romance along with a fondness for a now distant past.

In Sombra, Santos, Tomás, and Ana’s journey in search of the older musician, brilliant use of Lara’s compositions create emotional and cultural depth in his main characters, effectively revealing disappointment and loss with a deeper longing for love and personal meaning as the brothers “come of age.” In particular, Lara’s “Azul” and “Palmera,” evoke a tropical, mid-twentieth century feeling closely associated with the eastern port city. Other songs such as “Palmera,” “Imposible,” “Tus pupilas,” “Farolito,” and “Veracruz” similarly establish a romantic tone during certain scenes in Güeros.

As the film unfolds, Tomás leaves his mother and home in Veracruz (with guitar in hand) to go live with Sombra in Mexico City. During this transition sequence, the song “Azul” plays, sung by the popular composer’s most beloved female interpreter (Veracruz native) Toña la Negra. In portions of this section, the soundtrack features a heavy echoing of Toña la Negra’s recording that reflects the anxiety Tomás is feeling as he first arrives in the capital.

Shortly thereafter, a version of “Veracruz”–this time with Lara playing and singing–is heard as the boys sit idly outside their apartment complex, smoking cigarettes and talking. Interestingly, the tune features lyrics that fondly remember the port town with its faraway “palm trees,” “beaches” and “star filled nights.” In the song, the singer pledges to “return one day.”

Big city adventure calls, however, and the next moment, Sombra notices Tomás listening to music on his portable cassette player in a parked car. He looks at the tape case and sees the name “Epigmenio Cruz.” “You still listening to this?” he asks his younger brother. Tomás nods, “Yes.” Shortly thereafter, the two brothers and their friend Santos are seen sharing the headphones, dreamily listing to Cruz. Their mission is now set.

As they make their way through among the tall glass buildings of the city’s southwestern sector, a verse of Lara’s “Imposible” as sung by Toña la Negra is heard. Their quest may be a difficult one but they are determined despite a deep sense of alienation.

Night falls and the boys come to the gates of the National University where the student strike is in full flower. They enter the main auditorium where organizer Ana is giving a passionate speech. As the three make their way, an innocent, childlike rendering of Lara’s “Azul” (now performed by contemporary singer songwriter Natalia Lafourcade) is playing. Ingeniously, Lafourcade’s version (she is from the Veracruz town of Coatepec) is mixed with the older, classic recording by Toña la Negra, thus blending Mexican musical past and present.

Ana then meets up with Somba, Santos and Tomás as they once again pile back into the car. The opening bars of Agustín Lara’s lighthearted classic “Farolito” (or “Little Light”-as in street light) plays as young Tomás watches Ana freshen up in the front passenger seat. The camera closes in on Ana’s eyes and lips as she applies her make up. Older brother Sombra also watches her with affection. Appropriately, “Farolito” continues to be heard in the background as our adventurers cruise the central city late at night. Street performers, drunks and garbage collectors move amidst the shadows.

Tomás, Sombra, Santos and Ana briefly attend a party celebrating the debut of a film. “Farolito” is still heard, now mixed with surreal electronics and conversation. Not long for the gathering, the four are soon back outside. Toña la Negra’s rendering of Lara’s tropical song “Palmera” plays in the open air as Ana playfully pushes Sombra in a nearby pool. The others quickly join in, frolicking in the water until a security guard comes and asks them to leave.

Ever persistent in tracking down the fabled musician Cruz, the boys and Ana eventually find Epigmenio in a cantina in Texcoco—to the east of the central city. Disappointingly, a sour-faced Cruz rejects the young man’s request. In Tomás’ defense, Sombra steps forward, informing the musician that the cassette was once their father’s. Shortly thereafter, the film ends as Lara’s tune “Veracruz” is heard one final time. They boys no doubt are disappointed in their musical idol but are nonetheless reunited as brothers, friends, and (in the case of Ana and Sombra) perhaps even lovers.

The ever-romantic Agustín Lara has long been associated with Mexican cinema. Now, with Güeros added to an already impressive filmography, one can imagine the composer would be pleased to learn his songs continue to inspire both artists and audiences worldwide.

Featured image: publicity still from Güeros, courtesty of Catanoia Films.

The post Bittersweet melodies of Agustín Lara in Güeros appeared first on OUPblog.

Brexit and employment law: a bonfire of red tape?

If you’ve been following the Brexit debate in the media, you no doubt will have noticed how European employment laws are frequently bandied around as the sort of laws that Britain could do without, thank you very much. As welcome as a giant cheesecake at the Weight Watchers Annual Convention, the European Working Time Directive is never far away from the lips of Brexiters, and is routinely cited as the one of the worst kinds of “red tape” laws coming out of Brussels. But have you ever stopped to think about the assumption that underpins such statements? That is the notion that all employment laws, including those that are designed to protect workers from excessive working hours, are in fact a barrier to economic growth. Cast as drivers of inefficient intrusions into management time, such employment protection measures are deemed to be unnecessary pieces of social regulation, which must be stripped back. By doing so, employers would be rendered free to co-ordinate their labour force as they see fit, thus retaining flexibility in their internal labour markets, and increasing employment rates and overall economic growth.

In this blog, I aim to probe the received notion that employment laws are inefficient. A slew of justifications for this claim will be examined, before moving on to focus on the counterclaims made by economists who argue instead that employment laws promote economic efficiency. Ultimately, as lawyers, and not economists, this is not an issue for us to resolve, but a flavour of the economic arguments in favour of and against the introduction and preservation of employment laws in a countries’ legal order is a useful thing to understand. Whenever proposals for reform of employment law are suggested by government, it is particularly eyebrow-raising how frequently some of the claims and counterclaims we are about to examine are in fact versed as part of the relevant debate.

As welcome as a giant cheesecake at the Weight Watchers Annual Convention, the European Working Time Directive is never far away from the lips of Brexiters, and is routinely cited as the one of the worst kinds of “red tape” laws coming out of Brussels.

Turning first to the claim that employment laws are inefficient, it is contended that countries with policies encouraging flexible labour markets and less rigid employment laws will have companies that generate higher stock market returns: since the likelihood of being fired is greater in the absence of job security protections such as unfair dismissal laws, employees will invest greater effort to succeed. They will do so in order to minimise the scope for them to be discharged, and as such, will achieve greater satisfaction in their jobs. This increased satisfaction rate translates into higher firm productivity and stock market prices. For the same reason, there is evidence to suggest that one consequence of increased employment protection legislation is a reduction in worker effort in their jobs, together with higher staff absences in comparison with workers with more limited employment protection laws, such as casual workers, temporary workers, and other atypical workers. In essence, countries who choose to introduce rigid employment laws are acting as surrogate regulators of the terms and conditions of the contracts of employment of employees and employers in their jurisdiction. By over-riding the independent judgments of workers and employers in favour of the collective and social interests of certain sections of society, efficiency is reduced. Although equity in the workplace might be increased via redistributive employment laws – although this point is not conceded by adherents of this view – efficiency is clearly impeded.

This view is countered by those who support employment laws. The principal rejoinder is that such laws act as positive factors contributing to an increase in the productive output of workers. The suggestion being made here is that an alignment between equity and efficiency is not impossible. For example, those in favour of employment laws will point towards the evidence that suggests protective employment laws do not have any negative effects on equality, productivity or unemployment, and that they may have a positive impact on innovation and productivity. The positive impacts suggested here may be attributable to the “efficiency wage” theory. This is the idea that better-paid and happier employees enjoying higher contractual benefits and treated well and appreciated by their employers in the workplace equates to higher productivity and firm value.

Whatever the outcome of the Brexit debate may be, one thing is for sure, and that is that the status of European employment laws will not be far off the agenda. By emphasizing the market-enhancing effects of European employment laws, the Remain campaign will try to highlight the positive effects of economic integration. On the other hand, the Out campaign will point to the adverse economic consequences of European legislation in the field of social and labour market policy that is “imposed” by the EU on the UK. Ultimately, the decision whether to stay or go will be left to the voters, but what does seem to be clear is that the claim regarding the role of employment laws in stifling economic growth is inconclusive, with as much published research providing evidence for the view that such laws may have positive implications for aggregate market rates of productivity, employment, and innovation.

Featured image credit: Paper tape table dispenser, by Lilly M. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Brexit and employment law: a bonfire of red tape? appeared first on OUPblog.

April 11, 2016

Lift the congressional ban on CDC firearm-related deaths and injuries research

Imagine that there is a disease that claims more than 30,000 lives in the United States each year. Imagine that countless more people survive this disease, and that many of them have long-lasting effects. Imagine that there are various methods for preventing the disease, but there are social, political, and other barriers to implementing these preventive measures. And then imagine that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is restricted from, or not funded for, performing research on the disease or how it can be prevented.

Unimaginable. But all this describes firearm deaths and injuries in the United States and the congressional ban on CDC performing research on gun-related morbidity and mortality.

Each year, about 33,000 people in the United States die of gunshot wounds. The US firearm-related mortality rate is more than five times higher than in Canada, 10 times higher than in Germany, and 40 times higher than in the United Kingdom. Those who survive gunshot wounds often face physical and psychological problems for the rest of their lives.

Although more scientific research is needed, we know that restricting access to firearms would reduce gun-related deaths and injuries. But for more than two decades, the CDC has been restricted from performing research on firearm-related deaths and injuries. This restriction is a result of the gun lobby’s profound influence on Congress.

The CDC performs its own research and funds much research at many academic institutions on many diseases and injuries of public health importance – from HIV/AIDS to Ebola, from influenza to hospital-acquired infections, from motor-vehicle injuries to tobacco-related diseases. Much of this research is epidemiological, examining the distribution (by time, place, person, and circumstances) and determinants (causes) of disease and injury in populations. Much of this research evaluates alternative approaches to preventing a disease or injury and minimizing its consequences by various forms of intervention.

Houston gun show at the George R. Brown Convention Center. Photo by M&R Glasgow. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Houston gun show at the George R. Brown Convention Center. Photo by M&R Glasgow. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.When it comes to gun-related injuries and deaths, however, the CDC is not permitted to perform research. This is outrageous in 2016 in the richest country, which has, by far, the highest rate of gun-related deaths among industrialized countries. It is as outlandish as the American Hospital Association hypothetically preventing CDC research on hospital-acquired infections, or automobile manufacturers preventing CDC research on motor-vehicle deaths and injuries, or cigarette manufacturers preventing CDC research on tobacco-related diseases.

Gun-related deaths will not disappear if we, as a nation, continue to keep our heads in the ground.

There are many common-sense measures that could be implemented to reduce gun-related deaths and nonfatal injuries. These measures include preventing people with mental illness from acquiring guns, banning civilian access to military ordnance, and mandating trigger locks and other forms of gun safety. We are much smarter preventing unauthorized use of smart phones than we are in preventing unauthorized use of firearms. Variants of all of these and other measures are being implemented in other countries that have far-lower rates of gun-related morbidity and mortality. None of these measures represent attempts by the government to make possession of guns illegal.

A cornerstone of public health is prevention. Another cornerstone is evaluation of the effectiveness of therapeutic and preventive interventions. Much needs to be done to prevent gun-related deaths and injuries in the United States. At the same time, research needs to be done to identify populations that are especially vulnerable and to assess the effectiveness of various preventive interventions.

CDC is the nation’s prevention agency. Preventing gun-related morbidity and mortality requires the active participation of CDC. But right now politics is being given priority over public health.

Imagine that this ban can – and will – be lifted. Then take action to ensure that this happens. Imagine how many deaths and injuries can – and will – be prevented.

Featured image credit: evidence by Benedict Benedict. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Lift the congressional ban on CDC firearm-related deaths and injuries research appeared first on OUPblog.

Addressing Japanese atrocities

After decades of tension over Japan’s failure to address atrocities that it perpetrated before and during World War II, the island nation’s relations with its regional neighbors, China and South Korea, are improving. Six weeks ago, for the first time in years, representatives of Japan’s Upper House resumed exchanges with Chinese parliamentarians. And in December, after the Japanese government long denied its coercive role in the abuse, the country’s prime minister, Shinzo Abe, apologized and offered financial compensation for Japan’s exploitation of tens of thousands of Korean “comfort women” (a euphemism referring to Japanese military sexual slaves during the country’s colonial rule of the Korean peninsula from 1910 to 1945).

Although these recent developments are welcome, Japan’s reconciliation with its neighbors and with its own dark past will remain incomplete and insincere unless and until it acknowledges a lesser known but no less grotesque category of its wartime offenses: human experimentation. Just as Europe would not countenance German refusal to own up to the Holocaust atrocities of Josef Mengele, so too should East Asia expect Japan to offer a full, genuine account of and apology for the “scientific” barbarities it perpetrated. Some of the human guinea pigs were American soldiers, so Washington should help lead the campaign to demand Japanese responsibility. The United States, however, must make amends of its own: prioritizing military development over justice, the government sought to cover up and benefit from these bio-experiments, and has never properly accounted for its shameful calculus.

This shocking episode is perhaps the most successful aspect of Japan’s whitewashing of history, even if we do know some details of what occurred. The Imperial Japanese Army’s Unit 731, led by Lieutenant General Shiro Ishii, conducted experiments on thousands of civilians and Allied soldiers during World War II. (Although no consensus exists about whether American prisoners of war were among the victims of Unit 731 specifically, they certainly were subjects of Japanese human experiments elsewhere.) These experiments, sometimes referred to as the “Asian Auschwitz,” included vivisections, dissections, weapons testing, starvation, dehydration, poisoning, extreme temperature and pressure testing, and deliberate infection with numerous deadly diseases (such as bubonic plague, cholera, anthrax, smallpox, gangrene, streptococcus bacteria, and syphilis). Had World War II continued, the Japanese planned to use biological weapons developed from these experiments to attack the US military in the Pacific Theatre and possibly even the West Coast of the United States itself.

Once the war had ended, the US government offered immunity and other incentives—including money, food, and entertainment—to over 3,600 Japanese government agents, physicians, and scientists involved in these experiments. Afterwards, some of these Japanese assumed prominent roles (including senior positions in the health ministry, academia, and the private sector) in postwar Japanese society, allegedly with the assistance or at least knowledge of the US government.

Some may argue that the US government bears no moral responsibility, as it did not directly participate in this human experimentation. But the United States declined to hold many of the perpetrators accountable, and benefited materially as well. US government officials were interested in the potential utility of the work of Ishii and other Japanese, however unethical, to the US military. Senior American officials felt that obtaining data from the experiments was more valuable than bringing those involved to justice, because the information could be used to advance the US government’s own weapons development program. American officials also were concerned about preventing other countries, particularly the Soviet Union, from obtaining the data. The incipient Cold War—and the superpowers’ attendant desire to secure competitive advantages and scientific advancements—thus chilled the US government’s enthusiasm for investigating and prosecuting Japanese human experimenters. American officials believed that their research would be useful in the arms race developing between the Soviet Union and the United States.

As with Japanese exploitation of comfort women, justice for Japanese human experimentation is long overdue. Illustrating that memorialization of these Japanese atrocities is an ongoing concern, just last August China opened a museum dedicated to researching and revealing this ghastly subject. Japan should, finally, now admit its wrongdoing, officially apologize, and offer meaningful, direct restitution to any surviving victims of the experiments. The United States, for its part, should apologize for offering amnesty to the atrocity perpetrators. Both Japan and the United States should declassify and release relevant records of the number, nationalities, and names of victims as well as deals struck between the two countries.

The fact that Japan has not fully acknowledged its wartime atrocities creates uncertainty about its true intentions and likely behavior, particularly as the country pursues a military resurgence and seeks to present a more unified front against North Korea’s increasing aggression. Japan’s horrific history will never be forgiven until it thoroughly and genuinely atones for all of its heinous crimes during World War II. Only then will Japan be more fully embraced by its neighbors and others in the international community as a sincere partner in establishing an honest account of the past and a more humane approach to the future.

Featured image: Lake Toya, Hokkaido. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Addressing Japanese atrocities appeared first on OUPblog.

April 10, 2016

Shakespeare’s linguistic legacy

William Shakespeare died four hundred years ago this month and my local library is celebrating the anniversary. It sounds a bit macabre when you put it that way, of course, so they are billing it as a celebration of Shakespeare’s legacy. I took this celebratory occasion to talk with my students about Shakespeare’s linguistic legacy. Often, we hear that legacy stated in terms of the vastness of his vocabulary and the number of words he contributed to the English language.

In the middle of twentieth century, Alfred Hart, then a leading authority on Shakespeare’s vocabulary, wrote that Shakespeare is … “credited by the compilers of the Oxford English Dictionary with being the first user of about 3,200 words.”

Sometimes, people take this to mean that Shakespeare actually made up 3,200 words, perhaps because it’s easier to say “Shakespeare coined thousands of new words” than “Shakespeare is credited by the compilers of the Oxford English Dictionary with being the first user of thousands of new words.”

But, as one student asked in my class, “If Shakespeare used so many new words, how did anyone understand him?”

Indeed.

It turns out that the 3,200 number suggested by Alfred Hart was a bit high. Shakespeare’s canon became so well-known and accessible that for a long time his was the earlier citation that could readily be found. As more texts have become available and searchable by computers and as OED lexicographers have revisited word histories, the number of first citations has dropped to about 1,600. That’s about the same amount as were created in the television series Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) in Helmolt, H.F., ed. History of the World. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1902. Author unknown, but the portrait has several centuries – from the Perry-Castañeda Library, University of Texas at Austin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) in Helmolt, H.F., ed. History of the World. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1902. Author unknown, but the portrait has several centuries – from the Perry-Castañeda Library, University of Texas at Austin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.You can do your own Shakespeare research, incidentally, by using the Advanced Search feature in the OED online. If you type “Shakespeare” in the search box and select “First Quotation” in the accompanying drop down menu, you’ll get the entries for which Shakespeare has the earliest citation (my search retrieved 1,614 citations). You can also search by individual plays if you want to get really specific.

It also turns out that Shakespeare was not alone in the practice of coining words, so audiences may have been used to a certain amount of verbal innovation and flexibility. Neology was quite the fashion in the late Renaissance period. Scholars estimate that during the years Shakespeare was writing, roughly 1588-1612, nearly 8,000 new words came into the language. (Vivian Salmon and Edwina Burness, drawing on The Chronological English Dictionary, give a figure of 7,968).

Many of the first citations from Shakespeare’s works were novel uses of existing prefixes and suffixes, like un– or –er, as in uneducated and swaggerer. It would be relatively easy—one might say it would be undifficult—to figure out their meaning.

Another way that Shakespeare created new words was by turning nouns into verbs, as in Measure for Measure, (Act iii, scene 2) where the Lucio tells the Duke (who is incognito, disguised as a friar), that Lord Angelo is strictly upholding the law in the Duke’s absence. Lucio explains that “Lord Angelo dukes it well in his absence.” Shakespeare packs a lot of meaning in the word duke. Try to rephrase the line without that verbed noun.

Shakespeare also used many adjective compounds, like hot-blooded, cold-blooded, green-eyed, bare-faced, dog-weary, ill-got, lack-lustre, and crop-ear, which would also be fairly transparent in context.

So, people could understand Shakespeare because many of his novelties words were grammatically and culturally transparent and there were really not all that many of them. If the average play had 3,000 lines, then less than only 1.5% of Shakespeare’s lines had a first-cited word.

Four centuries into Shakespeare’s legacy, perhaps the more important question is whether we can still understand Shakespeare’s words today. Not all of his new words are transparent today. Consider the compound fancy-free, which we know today from the expression “footloose and fancy-free,” meaning free of responsibilities. Shakespeare used the word differently though.

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Act ii, Scene 1), Oberon, the king of the fairies, recounts how Cupid’s arrow missed a young maiden (hitting instead a white flower that would then be used to create a love-potion):

Sir Joseph Noel Paton – The Quarrel of Oberon and Titania – Google Art Project 2. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Sir Joseph Noel Paton – The Quarrel of Oberon and Titania – Google Art Project 2. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.“But I might see young Cupid’s fiery shaft

Quench’d in the chaste beams of the watery moon,

And the imperial votaress passéd on

In maiden meditation, fancy-free.”

Shakespeare is using fancy-free here to mean “unaffected by love.” It’s the use of fancy that we still find in the expression “to fancy someone.”

Here’s another example, from Coriolanus, the tragedy about the Roman General Caius Marcius. In Act V. Scene 3, the title character affirms his love for his wife Virgilia, with an oath to Juno, the goddess of marriage:

“Now, by the jealous queen of heaven, that kiss I carried from thee, dear; and my true lip Hath virgin’d it e’er since.”

Shakespeare makes a verb out of the noun virgin, meaning that Coriolanus would hold the kiss dear and treasure it.

Words like fancy-free and to virgin challenge us and sometimes confuse us. They send us to the dictionary and to context in the plays. They force us to listen and read slowly, again and again. They make us ponder language. This is the part of Shakespeare’s linguistic legacy that I like to celebrate. It makes me think about his words, perhaps even to virgin them. Fancy that.

Featured Image Credit: “Procession of Characters from Shakespeare’s Plays” by Unknown artist (manner of Thomas Stothard). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Shakespeare’s linguistic legacy appeared first on OUPblog.

Chills, thrills and surprises: ten years of freedom of information in the UK

The Freedom of Information (FOI) Act has been in the news again, when the controversial Independent Commission, much to the surprise of many, concluded the Act was ‘generally working well’, had ‘enhanced openness and transparency… there is no evidence that the Act needs to be radically altered’.

How can this be squared with the claims of Tony Blair, who passed the Freedom of Information Act back in 2000, that the law is one of his greatest regrets? Blair spent some time in his memoirs bemoaning how terrible and counter-productive FOI was:

The truth is that the FOI Act isn’t used, for the most part, by ‘the people’. It’s used by journalists. For political leaders, it’s like saying to someone who is hitting you over the head with a stick, ‘Hey, try this instead’, and handing them a mallet. The information is neither sought because the journalist is curious to know, nor given to bestow knowledge on ‘the people’. It’s used as a weapon.

He’s not the only politician who has fallen out of love with transparency. David Cameron began his time in office with a ringing commitment to make his government the most transparent ever and initiate a revolution in openness. In 2012 he was a little less enthusiastic, speaking of how FOI can ‘occasionally fur up the arteries of government’ and by 2015 he was referring to it as just another ‘buggeration factor’ alongside judicial review and Health and Safety laws. The Leader of the House of Commons Chris Grayling also complained that FOI was being abused by journalists (though the Daily Mail pointed out that he was quite a fan of FOI in opposition).

So why do politicians dislike it so much?

In part the unhappiness is due to a politician’s natural dislike of “surprises.” FOI is the antidote to “spin,” amid a growing emphasis on “spin.” FOI can often cause embarrassments and scandal, digging up stories and delving into forgotten corners. Imagine being a politician and think of the effect of seeing stories such as MPs’ expenses, councils’ use of credit cards or an online list of which politicians supported what controversial decisions. You can also glance over this fascinating list of snooping councils, inappropriate use of social media and escaped convicts revealed by FOI. Spare a thought also for the parish of Walberwick where the council resigned on masse over a combination of cover ups and Christmas trees exposed by FOI requests.

Image credit: blair 2 by Matthew Yglesias. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: blair 2 by Matthew Yglesias. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Another claim made is that FOI stops everyone writing things down, the so-called chilling effect. Despite endless discussion and Cabinet Secretary Gus O’Donnell’s rather creative warning that officials are ‘working on Brexit plans in their head’ to avoid FOI, we found the chilling effect to be a myth (as did a Parliamentary committee). The quality of official advice or government records is no worse and emails and “sofa government” have led to far more change than FOI. Despite this lack of evidence, it is still being talked about and the danger is it can becomes a self-confirming myth.

A final reason for their unhappiness has to do with how politicians meet FOI: senior politicians and officials only ever see a few requests, often the most sensitive or most potentially damaging, and often from journalists. They get a very narrow, and negative, view of what requests are received and are prone to view FOI as a ‘problem’ and see it as ‘abused’ by the media. Rather than Iraq, Tony Blair was upset with how FOI revealed who had visited him at chequers (and who gave him an iPod). This also plays into claims that FOI is an alleged resource burden as [some] local councils and police forces have claimed.

So, politicians easily go off FOI, through a mixture of unpleasant surprises, (imagined) chills, and bad memories. However, here hangs a paradox. FOI needs support from politicians to flourish and those very politicians most at risk from exposure need to get behind it or at least tolerate it. FOI will still be around in another 10 years but so will the complaints.

Featured image credit: p1090090 by generalising. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Chills, thrills and surprises: ten years of freedom of information in the UK appeared first on OUPblog.

China’s smoldering volcano

China’s phenomenal economic growth has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty in recent decades. It has also produced massive social change, dislocation, resentment, and hostility. China’s leaders point to a growing gap between rich and poor as the primary source for unrest. Martin Whyte, a Harvard sociologist, argues that income inequality is not the real problem. Based on a series of national surveys, he believes the main reasons for popular anger are “abuses of power, official corruption, bureaucrats who fail to protect the public from harm, mistreatment by those in authority, and inability to obtain redress when mistreated.” China, says Whyte, is sitting on an “active social volcano.”

Tens of thousands of urban and rural protests take place every year over lost wages, unemployment, land seizures, environmental pollution, the household registration system, crackdowns on religion, discrimination against migrants and minorities, and other issues. These widespread incidents can be attributed to resentment over inequalities in power rather than in income. The targets of popular rage are not the super rich but authority figures, usually at the local level.

A Touch of Sin, a 2013 movie directed by Jia Zhangke, vividly depicts this bleak view of Chinese society. Based on true events, the film presents four separate stories of rage and revenge replete with shocking murders and the suicide of a young migrant worker. In each case, ordinary people have so profoundly disaffected that they decide to take their destinies into their own hands. The men and women who commit crimes are not apprehended by the police, who are nowhere to be seen. This is an arbitrary society operating in a moral vacuum. Jia says his film is about how we tolerate injustice.” As for the title, “More than anything I think silence is a sin.”

A Touch of Sin has not been been shown in China.

Image: World Class Traffic Jam by joiseyshowaa, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Image: World Class Traffic Jam by joiseyshowaa, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

President Xi Jinping, who took office in 2012, clearly understands the threat that social injustice poses for the nation and for the Chinese Communist Party. His unprecedented anti-corruption campaign has been welcomed by Chinese citizens. But a concurrent effort to control information and to suppress opposition to the Party suggests that the problem is so deeply rooted that removing even a large number of bad officials—which already has been done, creating insecurity and opposition within the bureaucracy and military—does not go far enough. Corruption is a symptom pointing to the need for fundamental, structural reforms that would bring much greater transparency and accountability to government. But as Whyte notes, such reforms “would threaten very powerful vested interests among the political elite devoted to the preservation of the status quo.” Meanwhile, a slowing economy is producing more unrest as workers lose their jobs.

Distrust, alienation, anger, and violence are familiar themes for Americans who are experiencing the fallout from globalization, the disruption of new technologies, and are struggling with the injustices of racism. The United States is far from perfect. But China still lacks an independent legal system, adequate protection of human and labor rights, genuine freedom of expression, and predictable means to address grievances. Until such reforms can be accepted in Beijing, resentment will continue to rise and China’s smoldering volcano may eventually erupt.

Featured Image Credit: “Forbidden City” by IQRemix CC BY SA-2.0 via Flickr

The post China’s smoldering volcano appeared first on OUPblog.

Could a tax on animal-based foods improve diet sustainability?

The global food system is estimated to contribute 30% of total Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In this context, the EU has committed to reducing GHG emissions by 40% relative to 1990 levels by 2030 and by 80% by 2050. Apart from the necessary policies of citizen information and production regulation, could a consumer tax on the most Greenhouse gas-emitting foods be a relevant tool to improve diet sustainability? Could it combine greener and healthier diets with a limited social cost?

Fiscal policies are commonly used in the energy sector to enhance more sustainable options (through a carbon tax in some Nordic countries) or in nutrition to limit the consumption of unhealthy foods . Animal-based products, and in particular livestock, are the highest GHG emitters, and reducing their consumption could bring associated benefits in environment and nutrition. Indeed, red and cooked meat are primary sources of saturated fats, which are related to an increased risk of obesity and cardiovascular disease. Reducing meat consumption also raises a health inequality issue since these risks place a higher burden on lower socioeconomic populations.

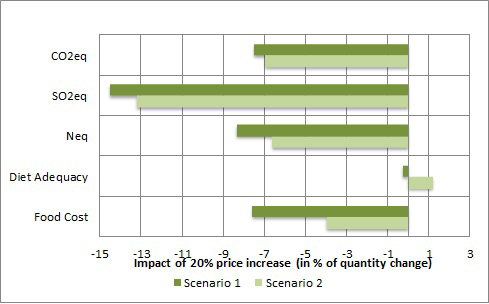

To address these questions, we have drawn two hypothetical environmental fiscal policies, one including and one excluding nutritional concerns. The first step consists of relating the food basket purchased to its GHG emitting potential and to a nutritional score expressing its “degree of healthiness”, (see Figure 1.) The second step consists of conducting an econometric study on food-at-home purchase choices. Changes in food purchased were used to compute the implied changes in environmental (i.e. CO2 for climate change, SO2 for air acidification, N for eutrophication) and nutritional indicators, as well as in food cost. The last step relates to measuring, for two tax scenarios, the impact of changes over four income and four age classes, thus considering equity concerns.

Figure 1 by France Caillavet, Adélaïde Fadhuile, and Véronique Nichèle, used with permission.

Figure 1 by France Caillavet, Adélaïde Fadhuile, and Véronique Nichèle, used with permission.We used a French nationally representative survey at the household level to analyse food-at-home purchases from 1998 to 2010. Our work shows that consumers are sensitive to the price of animal products and that a 20% price increase induces them to restrict their consumption, therefore reducing GHG emissions. However the content of the diet in some essential nutrients linked to animal products is also affected. A first scenario taxing all animal products (meats, fish, animal fats, cheese, other dairy products) reduces emissions by 7.5% for CO2, 14.5% for SO2 and 8.4% for N, but simultaneously degenerates diet quality (-0.3%) (see Figure 2.) In a second tax scenario, the diet adequacy score changes are favourable (+1.2%) when fish and dairy products other than cheese are not affected by the price increase. This second scenario still induces a 7.0% CO2 decrease, as well as 13.2% SO2 and 6.6% N reduction. The carbon reduction represents 99kg CO2 eq/year per household, which is close to the emissions produced by a 700km run with a Renault Clio. Therefore, beneficial synergies between environment and nutrition goals may be achieved through the design of a tax.

Figure 2 by France Caillavet, Adélaïde Fadhuile, and Véronique Nichèle, used with permission.

Figure 2 by France Caillavet, Adélaïde Fadhuile, and Véronique Nichèle, used with permission.The main counter argument of a tax is its social cost. The second scenario, which improves the quality of the diet, induces a loss of 4% in the budget for food-at-home consumption, i.e. 61 euros/year per household. This relative impact is smaller than the impact on emissions. However, social equity is also affected; such a tax is regressive. For example, we observe that this tax generates higher losses for the two lower-income groups, particularly for households with middle-aged heads. In a cost-benefit analysis, a higher monetary cost of food for some population groups could be acceptable if it were compensated by higher nutritional effects, but this is not the case; the reduction in nutritional inequalities across households is very limited.

Sustainability is a multidimensional concept and taking into account the environment, nutrition, and social equity dimensions leads to the necessity of trade-offs, as illustrated here in the case of a taxation policy applied to animal-based foods. Some environmental benefits must be exchanged for securing nutritional goals, and there will be some extra cost for the consumer. Therefore, a tax scenario needs to involve a compensatory mechanism. Our results raise two further policy issues. First, the trade-off between environment and nutrition could be improved by using proportional tax rates on both levels of emissions and nutritional contents, on the basis of combined healthy and sustainable guidelines. Second, the loss in purchasing power could be compensated by using the revenue of the tax. A fiscal policy combining subsidies with taxes could address differing nutrient needs and purchasing behaviours among households, as well as equity issues. A price policy is among the more persuasive signals to be addressed to consumers to modify their diet, and can fulfil simultaneously environmental, nutritional and equity goals.

Headline image credit: Meat products sausage cutlets by Counselling. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Could a tax on animal-based foods improve diet sustainability? appeared first on OUPblog.

What would Shakespeare do?

We’ve heard a lot lately about what Shakespeare would do. He’d be kind to migrants, for instance, because of this passage from the unpublished collaborative play ‘Sir Thomas More’ often attributed to him:

Imagine that you see the wretched stranger

Their babies at their backs, with their poor luggage,

Plodding to th’ports and coasts for transportation (Scene 6: 84-6)

He could offer Republican candidates some advice on how to take down a threatening tyrant; one topical commentator urged Marco Rubio to play Brutus to Donald Trump’s Caesar (although we all know what happened to Brutus), while another addressed Hillary Clinton as ‘Lady Macbeth of Little Rock’ (I’m guessing that means she shouldn’t be President). David Cameron put the laboured into Labour in a string of Shakespeare title puns at a recent Prime Minister’s Question Time, suggesting that the opposition reshuffle was ‘a Comedy of Errors, perhaps Much Ado About Nothing?’. Shakespeare is even interested in climate change, even if his view (in A Midsummer Night’s Dream) that climate change is caused by fairies fighting, is a little off-message:

The spring, the summer,

The childing autumn, angry winter, change

Their wonted liveries, and the mazèd world

By their increase now knows not which is which (2.1.114-7)

It surely can’t be long before Shakespeare makes an appearance in the EU referendum debates, not least because Boris Johnson is to publish a book on the playwright during this anniversary year.

So What Would Shakespeare Do? (WWSD?) about the current Shakespeare excitements for the 400th anniversary of his own death? Does he have anything to comfort a world weary with books, exhibitions, film festivals, television programming, and other anniversary paraphernalia?

Let’s look to his reflections on his own vocation. Shakespeare’s own depiction of the poet tends towards the sardonic. At the beginning of Timon of Athens a Poet is one of the hangers-on at Timon’s generous table. But the Poet is not an admirable figure. Rather, he is mocked for his overblown and circumlocutory language:

You see this confluence, this great flood of visitors.

I have in this rough work

Shaped out a man

Whom this beneath world doth embrace and hug

With amplest entertainment. My free drift

Halts not particularly but moves itself

In a wide sea of wax. No leveled malice

Infects one comma in the course I hold,

But flies an eagle flight, bold and forth on,

Leaving no tract behind.

Shakespeare statue in Lincoln Park, Chicago by Scott Rettberg. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Shakespeare statue in Lincoln Park, Chicago by Scott Rettberg. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.In case we do not realize that this is pompous and incomprehensible, his fellow beneficiary, the Painter asks ‘How shall I understand you?’. The Poet presents his poem to a busy Timon, has an argument with Apemantus about whether poetry is all lies, and seems to get little benefit for his pains. At the end of the play he returns to Timon, who treats him with scabrous contempt and drives him away. So much for the Poet’s role in praising, comforting, or even earning himself a living; on every count this Poet fails, and the overall effect is to puncture the claims he, or we, might make for his art. Timon suggests that poets’ claims for their own importance are unearned and narcissistic.

The problem – or perhaps the joy – of WWSD? is that it’s always possible to find an alternative or contradictory viewpoint across the works. Take Europe: Shakespeare may be the great spokesman for either the leave or the remain EU campaigns, depending on whether we go with ‘Naught shall make us rue / If England to itself do rest but true’ (the closing lines of King John) or with the King of France’s wish for ‘neighbourhood and Christian-like accord / In the[…] sweet bosoms’ of England and France. In general, the answer to WWSD? is almost always: he’d do just what I’m already planning to do myself (support migrants, oppose Trump, vote for Brexit, or whatever), but with the verbal magic to make it sound so much better. Perhaps we read Shakespeare rather as we read our chosen newspaper: to have our own opinions and perspectives confirmed rather than challenged. Interpretation and enjoyment is bound up with a kind of confirmation bias.

This intrinsic ambiguity is true for Shakespeare’s own views on poetry. If the Poet in Timon of Athens is a parasite on the emotional and material fortunes of others – and the Poet in Julius Caesar is torn to pieces for his ‘bad verses’ – the poet figure of the Sonnets has a quite different status:

Not marble, nor the gilded monuments

Of princes, shall outlive this powerful rhyme (Sonnet 55)

This poet would be worthy of recognition and celebration, even four hundred years after ‘death and all-oblivious enmity’. In the face of our own inevitable extinction, what remains is poetry. We only know Shakespeare died 400 years ago because of the words. Across his plays and poetry, he has amply enacted the memorial premise of the sonnets. So perhaps the answer to WWSD? on the question of his own anniversary celebrations is, he’d accept the honour proudly. Perhaps he would share it with his fellow actors with whom he worked collaboratively for almost two decades (imagine Shakespeare’s Oscar speech). I like to imagine him hugging to himself the secret glee that he had outlived his audacious contemporary Christopher Marlowe so decisively. But above all, he would accept as his due the confirmation of his own bold claim, that his ‘powerful rhyme’ had indeed outlived almost everything else.

The post What would Shakespeare do? appeared first on OUPblog.

Note to Pope Francis: sex is more than just sex

Pope Francis is boldly liberalizing Catholic teaching on sexual matters. Or so it is commonly believed.

Whether it is just or unjust, accurate or inaccurate—and perhaps my note will turn out to be less a reminder to the pontiff than to those who hear and read him inaccurately—Pope Francis is enthusiastically applauded by a broad and admiring audience for bringing the Roman Catholic Church up to date on matters of sexuality, primarily by putting them into a proper perspective. In earlier ages of the Christian Church, both East and West, its canons and its teachings always understood human sexuality as having a very powerful effect upon the human soul, and hence much deserving of pastoral counsel to safeguard its salutary employment. Now, however, this view has become unfashionable and many believe the Pope is helping the Church to finally realize (as the nineties’ refrain echoed, from the dismissal of Bill Clinton’s amorous adventures to the glib laugh-line on Sex and the City) that sex is “just sex,” not really a big deal at all, and certainly nowhere near the center of the moral or spiritual life.

But what if, to the contrary, this view—reflected in the title of the 1998 gay-oriented film, Relax… It’s Just Sex—is profoundly mistaken? (And of course, if sex is just sex, what’s so important about ‘coming out’?) Rather, I believe that this source of the most ancient and enduring prohibitions and exhortations is psychologically, morally, and spiritually a very “big deal” indeed. And if this is the case, then the ascendancy of sexual laissez-faire in the West—from the glib and ubiquitous employment of internet porn among young people, to the hook-up culture that serves as its less disembodied corollary, to the perceived imperative to normalize carte blanche every conceivable mode of sexual activity— is likely to have powerful and unforeseeable consequences.

It was not, after all, some wizened ascetic, but the great critic of asceticism, Friedrich Nietzsche, who wrote: “The degree and kind of a man’s sexuality reach up into the ultimate pinnacle of his spirit.” And his older contemporary, Søren Kierkegaard, from the time of his first publication, made sexuality and the erotic central to his understanding of the human condition, with the first half of Either/Or focusing upon the erotic, the aesthetic pleasures of seduction, and the question of “the aesthetic validity of marriage.” Both figures anticipated the appraisal of Freud and the psychoanalytic movement concerning the inestimable importance of libido. Nor is this merely a modern view, as witnessed by Plato’s preoccupation with eros and sexuality not only in the two dialogues devoted to these topics, the Symposium and the Phaedrus, but in many of his other writings. The quintessentially modern Marquis de Sade, whose deliberately outrageous writings invariably return to ethical and political matters, and who was elected to the revolutionary Convention nationale, argued stridently that the liberation of humanity cannot be complete until all sexual norms are systematically subverted, a task that requires not placid atheism but systematic blasphemy to level all hierarchies—thereby positing sexual libertinism as the sine qua non of human freedom. Modern neuroscience, for its part, has shown the far-reaching effects on body and soul of sexually related hormones and biochemicals.

But perhaps the most significant evidence that sex, and the erotic in general, is centrally important to human existence comes from Jewish and Christian scriptures and theologians. The unabashedly erotic and often overtly sexual “Song of Songs” has long been understood as an allegory of the relation between God and his people. And throughout the Old Testament, idolatry (the pursuit of many gods) is linked to prostitution and infidelity (the pursuit of many sexual partners) and even called “spiritual fornication.” (Wisdom: XIV: 12) In the New Testament, and in the liturgies that explicate it, the relation between Christ and the Church is seen as analogous to that between bride and bridegroom, with more than a few references to the bridal chamber where the marriage is consummated. But if there are absolutely no norms for the wedding night, let alone what precedes or follows it, what does this imply for our relation to the divine? This theme is discussed with great eloquence by the Byzantine philosopher and theologian, St Maximus the Confessor, embraced by both Catholic and Orthodox confessions. For Maximus, in the words of contemporary Greek theologian Metropolitan Hierotheos Vlachos, God “is both eros and the object of eros,” for “as eros He moves toward man, and as the object of eros He attracts to Himself those receptive to His eros.” And in the words of Maximus himself: “God stimulates and allures in order to bring about an erotic union in the Spirit; that is to say, He is the go-between in this union, the one who brings the parties together, in order that He may be desired and loved by His creatures.”

All of this has been obscured in the West, in no small part due to the fundamentally misguided work Eros and Agape by the Swedish theologian Anders Nygren. This book argued that eros is a pagan and selfish kind of love, in contrast to the purified, properly Protestant love the author believes is called agapē. And of course, given this belief, sexuality would not necessarily possess any spiritual dimensions, apart from its conformity to certain seemingly arbitrary, externally imposed regulations. But the Early Church never made that distinction, saw the two modes of love as interwoven and interrelated, and embraced eros as not only central to the spiritual life, but situated at its very heart. And if this is the case, disordered sexuality would have profound implications for our relation to God and one another, just as was understood in the ancient Jewish perception of a link between infidelity and idolatry, with the latter not uncommonly entailing sexual licentiousness and (as with the worship of Moloch or Baal) the ritual sacrifice of children.

Within a secular milieu that takes the belief in God as holding no more than marginal appeal—as no longer a “living options,” in the words of William James—the link between sexual eros, religious eros, and the inner core of the human person will seem like a curious remnant of an archaic past, while even Nietzsche’s reference to “spirit” (Geist) will seem merely retrograde. But if there is a deity who resembles the God portrayed in the Jewish and Christian traditions, and moreover if the life of the spirit is what is most essential about the human condition, then sex is not just sex at all, but a matter of great importance, a mirror for understanding our relation to the other, a decisive clue to unlocking the cipher of who we each are, a powerful force for good or for evil, i.e. a “very big deal” indeed.

Featured image credit: Bed, by Nik Lanús. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Note to Pope Francis: sex is more than just sex appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers