Oxford University Press's Blog, page 522

April 14, 2016

Revitalising Cambodian traditional performing arts for social change

I am recently returned home (Australia) from six months on a music research project in Cambodia. There were, of course, the practical challenges of the type I quite expected. In the monsoonal downpours, getting around in central Phnom Penh meant wading through knee-deep, dead-rat kind of drain-water. In the thatched huts of the provinces, malarial critters droned their way under my net by night. Gastro and heat exhaustion laid me flat.

Some challenges lay deeper. I learnt of the land grabs, abysmal garment factory conditions, one of the highest suicide rates in the world, child sex trafficking, orphanage scams, rampant domestic violence. I witnessed the abject poverty, and the political absurdities. At the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, I listened to a man recount in depth his experience of Pol Pot’s genocidal regime, including the murder of his wife and a dozen other family members.

But over the course of my stay, I came to believe there’s hope for Cambodia despite the challenges – and that the performing arts can play a unique and driving role in social change.

Revitalising endangered music traditions

Traditional music in Cambodia was silenced during the years of genocide and civil war. Up to 90% of all musicians and other artists lost their lives, and an estimated half of all traditional genres were lost.

Since at least the mid-1990s, strenuous efforts have been made to revitalise traditional performing arts. With the assistance of non-government organisations like Cambodian Living Arts, there has been significant progress, though much remains to be done. Elderly master-musicians, aware of the urgency of the task, are striving to pass on their skills to the younger generations while they still can.

The only remaining actively teaching master-musician of the traditional music genre kantaomming, Seng Norn (right), teaches his students. Photo by the author, Siem Riep province, 6 July 2014.

The only remaining actively teaching master-musician of the traditional music genre kantaomming, Seng Norn (right), teaches his students. Photo by the author, Siem Riep province, 6 July 2014.For their part, those young people with an interest in the intangible cultural heritage of their country are taking up the challenge with fervent commitment.

They understand the importance of their time-honoured cultural traditions for their individual and collective identity. But increasingly, there is also awareness that traditional arts can act as a tool for social change.

Pich Sarath is one case in point. He is a passionate young man spearheading the revitalization of chapei, one of many Cambodian music instruments and traditions nearly annihilated during the genocide. The genre is currently under consideration for inscription on UNESCO’s List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding.

If Sarath has one eye on ensuring the future of Cambodia’s beautiful endangered cultural heritage, the other is squarely on issues of social justice.

A couple of months ago, Sarath travelled to one of the rural provinces to support villagers in their protests against deforestation, which is stripping their land and their livelihoods bare. Recent demonstrations have only incited the ire of local officials and military police, and put the villagers at risk of harm. “But if we play and sing Chapei about it,” Sarath shook an earnest finger at me, “it’s harder for them to get angry.”

Pich Sarath plays and sings traditional instrument/genre “chapei” on a rural village tour of the “Khmer Magic Music Bus”, 28 October 2015. Photo by the author.

Pich Sarath plays and sings traditional instrument/genre “chapei” on a rural village tour of the “Khmer Magic Music Bus”, 28 October 2015. Photo by the author.The New Cambodian Artists are another example, an energetic group of female dancers aged 18 to 25 who are exploring Khmer classical music and dance in contemporary ways. In a country where gender disparity and gender-based violence are rife, the group both advocates for, and embodies, female empowerment. By profiling the traditional performing arts in new ways, the boundaries these young women are pushing are not only artistic, but decidedly social and political too.

New Cambodian Artists in rehearsal. Siem Riep, Cambodia. Left to right: Son Srey Nith, Khon Srey Nuch, Kong Seng Va. Photo: Matthew Harper, June 27, 2015. Used with permission.

New Cambodian Artists in rehearsal. Siem Riep, Cambodia. Left to right: Son Srey Nith, Khon Srey Nuch, Kong Seng Va. Photo: Matthew Harper, June 27, 2015. Used with permission.And then there are the young performers (mostly in their late teens and 20s) of the opera-like tradition “yike”, who present the traditional tale of Mak Therng to local and tourist audiences at the National Museum in Phnom Penh. In the story, Therng is a good-hearted farmer whose beloved wife is abducted by the king’s son. Deciding he must try to reclaim her, Therng daringly takes his grievance to the king.

In a country where corruption is rife and democracy a fluid concept, the work’s themes of power, authority, fairness, and justice are sensitive ones.

Mak Therng mourns the abduction of his wife. Scene from the Yike opera Mak Therng. National Museum of Cambodia, Phnom Penh. Photo by the author, 26 June 2015.

Mak Therng mourns the abduction of his wife. Scene from the Yike opera Mak Therng. National Museum of Cambodia, Phnom Penh. Photo by the author, 26 June 2015.In the original version of this old folk tale, the king defends the actions of his son. But in the present-day iteration, director Uy Ladavan chooses to discard the time-honoured ending. In her new version, the king sides with the farmer in his quest for justice.

Artistically, the difference is minor.

Socially, it is momentous: it offers a new vision for Cambodia, a vision wherein the vulnerable and disadvantaged feel able to stand up for their rights, and those with power assume fair responsibility for their actions.

In search of incredible

The raw tragedy of Cambodia seems everywhere. One day I saw it in the frayed rope tying a toddler to a garbage cart, to keep him close as his mother collected empty cans in the searing heat. Another day, it was thick in the air as I passed by the small group of women yet again protesting their land rights, David-and-Goliath-style, outside the Phnom Penh World Bank office.

And on a sultry afternoon, as I cycled through the heat, I saw it writ large on the old torn T-shirt of a young father sitting idle on the steps of his dilapidated rural hut, cigarette dangling, naked children playing in the dirt nearby. “In Search of Incredible”, read the T-shirt slogan. It made me swallow hard.

But that change is afoot.

Youth, the under 30s, make up two-thirds of the Cambodian population. They are socially aware, and curious, and earnest. They recognise that the country’s potential is at least as great as its challenges.

And increasingly, they are exploring socially and culturally relevant, creative, non-confrontational tools like traditional music to drive change.

In spite of all its heartrending challenges, I left Cambodia with the sense that it really is in search of incredible. And the traditional performing arts are proving a formidable tool in that search.

Featured image: A scene from the Yike opera Mak Therng, produced by Cambodian Living Arts. National Museum of Cambodia, Phnom Penh. Photo by the author, 26 June 2015.

The post Revitalising Cambodian traditional performing arts for social change appeared first on OUPblog.

What is the most important word in historical scholarship today?

SoulCycle. Juicing. The Making of a Murderer. Just as culture is beset by trends, so too is academia. For historians, trends can come in many forms, from growing fields of inquiry to new methods of analyzing well-trod scholarship. For example, while the Civil War is one hundred and fifty years behind us, scholars continue to unravel new findings by applying unique perspectives to issues long thought buried. To get a sense of where the field was going, we wanted see through the lens that historians are now using to evaluate the past. We asked historians to name one important word in historical scholarship today.

[View the story “What is one important word in historical scholarship today?” on Storify]

Featured image credit: Providence Skyline, by boliyou. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What is the most important word in historical scholarship today? appeared first on OUPblog.

April 13, 2016

Bosom, breast, chest, thorax… Part 1

In the recent post on bosom, I wrote that one day I would perhaps also deal with breast. There is nothing new I can say about it, but perhaps not all of our readers know the details of the word’s history and the controversy about its origin.

Breast has related forms in all the Germanic languages. At one time, it belonged to a declension with shifting stress. Consequently, the root vowel occurred in two different forms: stressed and unstressed. To understand the situation, compare the highlighted vowels in Engl. native and valid versus nativity and validity; in both cases, a fully-articulated vowel alternates with schwa. Or compare mortal and mortality. Later, Germanic stress was fixed on the first syllable, and the languages generalized either the full or the reduced grade of the vowel. Therefore, Old English had brēost, with a long diphthong, while Gothic (a Germanic language recorded in the fourth century) had brusts: u continues Proto-Germanic schwa. Modern German also has Brust. The choice was probably arbitrary.

An indispensable image of the dual.

An indispensable image of the dual.The most conspicuous features of the word for “breast” in the various old languages are its predominant use in the plural and its occurrence in all three grammatical genders. In Gothic and German, it was feminine. In Old Icelandic, it was neuter, while Old Engl. brēost has been recorded in all three genders. As early as 1882, Friedrich Kluge, the famous German scholar whose name still graces the title page of the main etymological dictionary of German (now in its 25th revised edition), explained the word’s attraction to the plural by the fact that at one time it had been a dual. Today we distinguish between the singular and the plural, but in the past the dual was their equal partner. For example, different forms existed for we and you, depending on whether the two of us or all of us, the two of you or “y’all” were meant. Some nouns most often occurred only in the dual. Predictably, this usage affected the objects that are more often spoken about in pairs, such as eyes and ears. In Old Germanic, the dual went over to the plural, and only some pronouns and endings sporadically retained the ancient category.

Kluge’s suggestion found immediate support and is now commonplace, but one wonders why breast had to be dual. The most obvious answer seems to be that at one time the word referred to a woman’s breast (it will be remembered that a similar conjecture was also made and rejected about bosom), but no evidence substantiates this idea. As a matter of fact, the little we know about the early history of breast points in the opposite direction. Also, two nipples on a man’s breast are as visible as two female breasts, even though much less useful. In any case, when our word began to be used in the singular and plural, it could choose its grammatical gender in a somewhat unpredictable way.

Not every breast needs a breastplate.

Not every breast needs a breastplate.The initial form must have been the neuter dual (later plural). The way from the neuter plural to the feminine singular is short, for those forms tended to coincide (hence the situation in Gothic and German). However, the neuter plural could as painlessly yield the neuter singular (this is what happened in Old Icelandic). Only occasional occurrences of Old Engl. brēost in the masculine arouse surprise, but language and logic are often at cross-purposes, or, to put it differently, language develops according to the logic that often escapes us. Very much in its history depends on chance rather than choice. Byrne “armor, hauberk” was called brynja by the marauding Vikings, and the Old Norse word must have been known only too well in Anglo-Saxon England (readers of English chivalric romances will of course remember byrnie). One sign of the popularity of the Scandinavian word is its use in Russian (bronia— stress on the second syllable—“armor”). Brynja and breast are, to use the vague formula of the etymological jargon, are distantly related (possibly, but not certainly, through Celtic; the names of weapons and other terms related to warfare are typical migratory words). In any case, hauberks were worn on men’s breast. This circumstance might have suggested to the speakers of Old English the masculine gender of brēost. Mere guessing, as Skeat liked to say.

The origin of breast poses many problems; yet the verdict would be not “unknown” but “controversial” or “disputed.” The Gothic Bible is a translation from Greek. In it brusts is used for two words in the original: one does mean “breast” (stēthos), but the other means “entrails, pluck” (splagkhna). Both are recognizable to English speakers from stethoscope and partly from spleen. Perhaps “belly” can be substituted for “entrails.” This lack of uniformity in the text, which is otherwise a model of care and linguistic acumen, need not bother anyone. A look at the words employed for human anatomy shows that the division of the body into limbs and “sections” varies from language to language. The anthologized examples are Germanic words for “arm/hand” and “leg/foot” and different terms for “finger” and “toe.” Outside Germanic, people do very well without such subtleties, just as outside English they manage to tell time without distinguishing between “watch” and “clock.” (While thinking about such idiosyncrasies of usage, I once decided to look up toe in Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current English and was informed that toe is a finger on the foot. Other dictionaries go out of the way to avoid such a funny definition and speak about “digits” or “terminal members,” which is even funnier. By the way, both finger and toe are words of almost impenetrable etymology.)

Byrnie: uncomfortable but masculine and safe.

Byrnie: uncomfortable but masculine and safe.We can assume that the Goths had one word for the entire front part of the trunk. “Belly” (or its inside), merging in Gothic with “breast” has a parallel in Slavic. Long ago, it was suggested (and later accepted) that cognates of Germanic brusts, as in Gothic, are Russian briukho “belly” (stress on the first syllable; similar forms occur in other Slavic languages) and quite probably Old Irish bruinne “breast,” from brusnio-. One notices at once that bruinne sounds very much like Old Icelandic brynja (the Gothic word was brunjo). Whatever one may say about “mere guessing,” brusts and brunjo are close! The second protects the first.

Given so many related forms in Germanic, Celtic, and Slavic, we can perhaps try to discover the etymology of the word breast. Here our authorities offer various solutions. Only one feature unites them: no one is quite sure where the word came from. Several reconstructed roots compete, and next week I’ll offer a short survey of the opinions known to me. But, and here I am returning to the beginning of this post, etymology is not all about the discovery of the prehistoric root. It is at least equally important to understand what happened to our word or words after they assumed the forms recorded in written and printed documents. Why does English have two very old words: breast and bosom? What made people borrow chest? This luxury, reminiscent of the existence of watch and clock, finger and toe, is sometimes not easier to explain than the origin of the most ancient roots.

To be continued.

Image credits: (1) Ancient Egyptian hoe and plough. Image from page 242 of “Anthropology; an introduction to the study of man and civilization” (1896). Internet Archive Book Images. No known copyright restrictions via Flickr. (2) West African chimpanzee. Image from page 62 of “Animal Life and the World of Nature; A magazine of Natural History” (1902). Internet Archive Book Images. No known copyright restrictions via Flickr. (3) “Ye Knight”. Detroit : The Calvert Lith. Co., c1874. Public domain. Library of Congress.

The post Bosom, breast, chest, thorax… Part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

Unwholly bound: Mother Teresa’s battles with depression

A psychiatrist’s couch is no place to debate the existence of God. Yet spiritual health is an inseparable part of mental or psychological health: something no psychiatrist should regard with clinical indifference. But what does spiritual or religious health involve? This can’t just include normalized versions of monistic theism – but the entire set of human dispositions that may be thought of in spiritual terms. This is too big a question to answer here, of course, but perhaps a step in the right direction may come from addressing another question:

What does spiritual health not involve?

Here are three things not to say about spiritual health:

The first thing not to say is that there is a single capacity or ‘mental faculty’ for spirituality in the human mind. Nothing could be further from the truth – there is no single spiritual capacity. Consider the numerous and heterogeneous mix of concepts that are considered spiritual or religious. Some concepts refer to supernatural agents (like spirits, gods, or God); others do not. Some concern afterlife beliefs, others ritualistic practices, still others involve sacred objects and holy persons. Some spiritual concepts are elements of our regular cognition, religion or no religion. Things like moral concepts (fairness and proportionality for example) are present in young children, long before they believe in a god.

Image Credit: “Take Back Your Health Conference 2015 Los Angeles” by Take Back Your Health Conference. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Image Credit: “Take Back Your Health Conference 2015 Los Angeles” by Take Back Your Health Conference. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.The second and related thing not to say, is that spiritual health is the same general condition for each and every ‘healthy’ person. Again, it is not. There is wide variation in the particular character of people’s spiritual health. For some, belief in God contributes to spiritual health. For others it does not. For certain individuals, membership in a religious community contributes to spiritual health – for others, it can even raise psychological issues!

The third and last thing not to say is that spiritual health is unbounded, unconstrained by human limitations of personality, culture, and circumstance. In the cognitive science of human decision making and reasoning, investigators write of something called ‘bounded rationality’. This concept recognizes situational constraints and personal limits on human decision making. No person is a perfect or Olympian reasoner. We get confused, we may be uninformed, and we make mistakes. Time is often not on our side.

Here, ‘bounded’ spiritual health should be at the center of the issue. A spiritually healthy person is not immune to forms of superstitious anxiety or ritualistic obsession. If spiritual health was perfectionist, spiritually unwelcome attitudes would not abide in people we class as ‘healthy’. The land of spiritual health has a cratered and uneven surface. It possesses peaks of spiritual sense and sensibility. The peaks, however, do not stand alone – they possess ragged edges and ravines…

To illustrate this point, I’d like to take a brief look at someone who, although iconic in her religiosity, may not have been spiritually healthy.

Consider Mother Teresa of Calcutta. She died in 1997. After her death, a book entitled Come Be My Light: The Private Writings of the Saint of Calcutta appeared. It holds a selection of her letters and diary entries, and was edited by Brian Kolodiejchuk, a priest.

Image Credit: ‘Mother Teresa Collage’ by @Peta_de_Aztlan. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Image Credit: ‘Mother Teresa Collage’ by @Peta_de_Aztlan. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.The book drew a lot of attention. The main reason? Many of the letters and entries consist of Mother Teresa’s descriptions of her suffering from a decades-long and disabling depression, or chronic form of emotional darkness. Depression, she reports:

Surrounds me on all sides – I can’t lift my soul to God – no light or inspiration enters my soul . . . Heaven, what emptiness – not a single thought of Heaven enters my mind – for there is no hope. . . The place of God in my soul is blank.

Chronic depression steals away whoever a person is. Mother Teresa desired to feel close to her God. Depression was a thief. It took the possibility of feeling close to God away from her. She reports that when she was in prayer in a public place: “People say they are drawn closer to God – seeing my faith. Is this not deceiving people? Every time I have wanted to tell the truth – that I have no faith.”

Prayer for many people is crucial to their presumed relationship with God. It helps to make him seem more real, more available. It did not do so for Teresa.

As Mother Teresa aged, she became more circumspect in her writing. However, her thirst for intimacy with God was never satisfied. Was her strife and emotional darkness compatible with spiritual health – bounded, and humanly constrained?

Reports from the Vatican indicate that Mother Teresa will soon be canonized. Alas, the future saint may have suffered needlessly due to an absence of psychiatric medical treatment. Apparently, the Church never considered that option for her. Mother Teresa received pastoral counseling, but it was cloaked in a somber and discouraging theology. Suffering from a felt absence of God, some of her counselors urged, was God’s way of drawing her close to him. This reading of her state of mind understandably did not reduce her misery. Perhaps she would have rejected secularized psychiatric attention, but unfortunately, we will never know.

Mother Teresa’s depression hung on her like an “unwholly weight” – making its full impact felt on a person who spent decades mired in conditions of abject poverty, illness, and death. As an important lesson to remember, it’s far from clear that this saint in Calcutta was spiritually healthy. Bound, or unbound.

Featured Image Credit: Stained Glass window by Louis Comfort Tiffany (1890), Yale University. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Unwholly bound: Mother Teresa’s battles with depression appeared first on OUPblog.

Technology, project management, and coffee yogurt: a day in the life of a librarian

There is one week each year when it is completely acceptable to fawn over libraries and librarians and all that they do for communities, institutions, and the world in general. Of course, you may find yourself doing that every week of the year, anyway, but we have great news for library fans — right now is National Library Week in the US. Follow along with the hashtag #NLW16 across social media to see how everyone is celebrating. To get a bit of insider information on the world of libraries, we talked to Eleanor Cook, Assistant Director for Discovery & Technology Services at East Carolina University, to find out how why she became a librarian, and what she gets up to every day.

What’s your first memory of a library?

When I was a child, my parents took me to our town’s public library regularly. We would spend an hour or more browsing the shelves and picking out books to check out – we would fill up an entire bag of books! Both my parents were veracious readers, and I obviously picked up this gene too.

What made you want to become a librarian?

As an undergraduate student, I was somewhat undecided about my future career direction and as I approached my senior year, I started considering different options. I landed a student job at the main library of my university, and fell in love. I worked as a student, then a graduate assistant and then as a staff member in the acquisitions department for almost 5 years before committing to obtaining my MLS. I never regretted this career choice; it has been an incredibly fulfilling career!

What’s the first thing you do when you arrive at the library?

Check my e-mail. And eat my coffee-flavored yogurt. I am famous for my obsession with this one particular yogurt.

What projects are you currently working on?

We are continuing to develop more User Experience projects – just completed a complete redesign of our database list page. Currently working on a complete review of staffing levels and future resource needs, with an eye of how digital is overtaking print and how that impacts the services we offer and the way we deliver them. I am also the co-chair of our campus women’s advocacy group which keeps me very busy.

What’s the best or most rewarding part of your job?

Having recently shifted my focus and responsibilities to the administration of library technology activities, I am learning all the time about new things I never dreamed I would be in charge of.

What part of your job do you think people would find the most surprising?

You might be surprised that it is possible for someone like me (never having been a programmer or a web designer or anything techie, really) to be able to successfully manage a group of people who are. Fortunately, my cataloguing and technical services background gives me an appreciation for the critical need for detail oriented projects and project management. I am incredibly fortunate to work with an outstanding cast of highly motivated and talented people.

What has been your proudest moment as a librarian?

I cannot not think of just one thing, but there are a few particular highlights:

Having the experience of working at a university library where the staff got to plan and oversee the conception, design, building and moving into a brand new building. Obviously the architects and contractors did the actual design and building, but we had input all along the way and I was heavily involved in supervising the moving of the bound periodicals stacks.

My other moments in the sun were serving as NASIG President in 2003 and receiving the Harrassowitz Leadership in Acquisitions Award from ALA ALCTS in 2011.

What are your hobbies outside of work?

Following indie rock groups and musicians, gardening, cooking, traveling, and being human caretaker to 3 rescue dogs and a cat.

Image credit: Books by Lubos Houska, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Technology, project management, and coffee yogurt: a day in the life of a librarian appeared first on OUPblog.

The wrong stuff: Why we don’t trust economic policy

In the 1983 movie The Right Stuff, during a test of wills between the Mercury Seven astronauts and the German scientists who designed the spacecraft, the actor playing astronaut Gordon Cooper asks: “Do you boys know what makes this bird fly?” Before the hapless engineer can reply with a long-winded scientific explanation, Cooper answers: “Funding!”

If an economist were asked, “Do you know what makes this economy fly?” the answer, in one word, would be “trust.”

Trust in economic policy—and economic policymakers—has been shattered in recent years: governments have failed to protect citizens from the worst effects of the financial crisis, regulators have failed to guarantee the integrity of the financial system, and governments around the world have straight out lied about the state of their economies. And American presidential candidates violate our trust by promising to be fiscally responsible while at the same time advocating plans that will blow up the debt and deficit.

Yet those candidates with the most outrageous policy proposals are at the very same time topping the polls and drawing huge crowds to their rallies. What’s feeding the public’s enthusiasm for them? In part, a feeling that the public’s trust has been violated. Trust that the economic system will protect the poor and middle class as well as it protects the rich. In the wake of the subprime mortgage crisis, many less well-off people lost homes and jobs, while well-heeled bankers who were responsible for the crash escaped largely unscathed, and certainly unpunished by the law. Shouldn’t the poor and middle class resent a system that is stacked against them?

A loss of trust is not unique to this country. Around the world, trust that regulators will ensure the fairness of financial markets has been lost. The Libor scandal—and, more recently, a foreign exchange scandal—saw a small cadre of London-based bankers manipulate key benchmark rates in order to turn a profit at the expense of non-insiders. Regulators on both sides of the Atlantic knew about Libor manipulation, but did nothing to intervene. Why should anyone trust their savings to a market that they know is rigged—and not in their favor?

And in some parts of the world, trust that the government will be truthful about the state of the economy is gone. China’s GDP figures for the last six quarters have shown virtually no variation and are almost identical to the government’s official target. Argentina’s government statistics office spent an entire decade issuing misleading statistics that supported the agenda of then-president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. The fraud was so great that the newly elected president declared a “national statistics emergency” and suspended the release of new data for the rest of 2016 while they clean up the mess.

Image credit: Bernie Sanders by Gage Skidmore. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Bernie Sanders by Gage Skidmore. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.Lest we think that the accuracy of macroeconomic statistics are of interest only to pointy headed economists like me, it is worth recalling that the European sovereign debt crisis erupted in October 2009 when Greece’s new government revealed that the actual budget deficit was twice as large as had been reported by the previous government.

The lack of trust in economic policy and policymakers has brought about the rise of anti-establishment parties in a number of countries. In Greece, the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party has been elected to Parliament in four successive elections since 2012. It is not inconceivable that this racist and xenophobic party could hold the balance of power if Greece’s next election ends in a hung parliament. Last September Britain’s Labour Party selected Jeremy Corbyn as its leader, one of the party’s the most left-wing members, who is so far outside of the mainstream that he is given virtually no chance of ever becoming Prime Minister.

The electorate in the United States is in a similarly bad mood and has, so far, supported insurgent, anti-establishment candidates in both the Republican and Democratic presidential primaries. What is surprising is that disaffected voters who feel that their trust has been violated are lining up behind candidates who promise to deliver more of the same.

The Brookings Institution-Urban Institute analyses of the tax plans of “fiscal conservatives” Ted Cruz and Donald Trump show that they would triple the federal government deficit to more than $1.5 trillion by the end of their first term in office. Their estimate of the increases under ex-candidates Marco Rubio and Jeb Bush were only slightly less. It may be that the Republicans are dispensing with candidates in reverse order of the sanity of their economic plans.

On the left, Bernie Sanders has been promising…..well, pretty much everything: free college tuition, higher social security and Medicare benefits, and huge infrastructure spending, all to be paid for with higher taxes. Analyses of the Sanders plan by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget and the Tax Foundation suggest that it would lead to an explosion of the federal government’s debt and a substantial reduction in economic growth over the next decade.

Much of the electorate has lost trust in our elected leaders, and not without reason. Nominating or, even worse, electing someone who will abuse our trust further is not the right answer.

Featured image credit: chart shares dax dow jones by markusspiske. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The wrong stuff: Why we don’t trust economic policy appeared first on OUPblog.

Homer: inspiration and controversy [Infographic]

The Iliad and The Odyssey loom large in European literary history and the tradition of epic poetry. Readers in both the ancient and modern worlds have been fascinated by the heroic exploits of Achilles and Odysseus and the idealized past the epics portray. Heinrich Schliemann was so taken by the events relayed in these Homeric epics that he sought to excavate the site of the Trojan War (Hisarlik, Turkey) that had been identified in 1822.

Although a man named “Homer” was accepted in antiquity as the author of the poems, there is no evidence supporting the existence of such an author. By the late 1700s, careful dissection of the Iliad and Odyssey raised doubts about their composition by a single poet. Since then, scholars have used literary and archaeological evidence to address the “Homeric question,” which involves debates about the identity of Homer, authorship of the Homeric epics, and the historicity of the society depicted in them. Though aspects of this question remain hotly contested today, most scholars now accept that the poems are the product of a gradual process of oral dissemination.

Explore more about the “Homeric question” and the influence of these epics in the infographic below. To discover more about Homer, the Iliad, and the Odyssey, check out the digital edition of the Oxford Classical Dictionary, which is now available for subscription.

Download the infographic as a JPEG or PDF.

Featured image credit: Homer, by Rufus46 (Own work). CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Homer: inspiration and controversy [Infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

April 12, 2016

How legal history shapes the present

The field of “legal history” studies the relationship that “law” and legal institutions have to the society that surrounds them. “Law” means everything from local regulations and rules promulgated by administrative agencies, to statutes and court decisions. Legal history is interested in how “law” and legal institutions operate and how they change over time in reaction to changing economic, social, and political conditions. It looks at people who are “governed” by law, as well as how those people try to influence law and legal actors. Thus, the field covers such diverse topics as the Roman law of wills, the social and economic conditions that brought down feudalism, the legal ideas motivating the American Revolution, the way that slave patrols kept the slave system in place, the legal regulation of business in the early 20th century, right up through the Black Power movement’s critique of the US criminal justice system.

The field has many subjects of study and many focal points, drawing on (and engaging with) studies of economics, religion, society, and culture. For a deeper understanding on the history of law, we asked Professor Alfred L. Brophy, one of the Editors of the American Journal of Legal History, to give us some insight into the past, present, and future of law’s relationship to culture over time.

How did you get into the field?

My first interest in legal history that I can remember came when I read Jerold Auerbach’s Unequal Justice in a class on modern American history. It’s a really exciting study of lawyers from the Progressive era to about World War II. It looks to the bar’s attempts to keep out Jews and others and how that had important effects on how justice was administered. And then things went from there. A lot of my interest in college was in quantitative methods of studying history; it was in law school that I really learned to love intellectual history.

How has it changed in the last 25 years?

The field has changed so dramatically over the past 25 years (basically the time since I graduated from law school), it’s hard to get a good grip on this. For instance, in 1990, legal history was largely about legal doctrine, often focused on judges and great writers. Now we are much more focused on the litigants and “objects” of law – people whose lives are led under the threat of prosecution, for instance. And we are paying so much attention to how those outsiders challenged and remade law. We are getting a lesson on this now in the United States with the “Black Lives Matter” movement.

What was your first published paper in the field of legal history about?

The first article I published after I started teaching was in AJLH—it was a quantitative assessment of litigation in a county in late 17th century. And it unfolded into some other cool work on the first law book written in British North America. Even before that article, when I was in graduate school, I submitted an article on southern constitutional arguments about the suppression of abolitionist literature. AJLH didn’t take that one. So AJLH gave me one of my first rejections, as well as one of my first publications! Given my personal experience with the journal – now about two decades ago – one of the things that I hope we will do a lot is promoting newer scholars.

What is your vision for the American Journal of Legal History?

I have incredibly high hopes and expectations for the AJLH under OUP’s leadership. I hope we’ll build on the legacy of the journal and that we’ll push the boundaries of legal history. I want us to publish work that cuts across nations and legal systems, that employs methodologies from the social sciences, that studies the role of all participants in the legal system, that links law to culture, that delves deeply into doctrine. I hope we’ll connect to contemporary movements that are asking about how legal reform happens. I hope we’ll be an important outlet for studies of the role of gender and race in the legal system. I hope we’ll do it all.

What role did legal history play in some of the recent high profile Supreme Court rulings?

Legal decisions are deeply connected to the past – often it’s the fairly recent past. But sometimes, especially in US Supreme Court decisions, judges take a longer view of history and how it informs the present. One place we saw this recently was Chief Justice Roberts’ opinion in the Affordable Care Act. He cited a number of opinions of Chief Justice John Marshall, to frame the rights of the federal government over issues of commerce. Decisions about the Second amendment, which deals with gun regulation, frequently turn to questions about what was permitted in the eighteenth century to gauge the amendment’s scope now.

What have you found particularly surprising in the field as it has evolved?

I think the thing that is most noticeable to me is how much legal historians have expanded the subjects of study. We now ask, for instance, what enslaved people thought about law and how they mobilized to change law. When I was in law school, the field was much more focused on what the “great” judge said. Now we care more, it seems, about what the almost anonymous person thought about law and how she took action on those ideas. The quality of the work is outstanding now. I’m always astonished at how sophisticated work is now. Part of this is the result of the growth of the field – but I think part is also due to the explosion of electronic databases, which make data much more easily available and have heightened the importance of interpretation.

Why is legal history relevant?

Legal history tells us about central questions of how we organize our society; it’s a terrific guide to all sorts of questions of morality and duty. It helps us understand and shape our government. I am always astonished at how often we hear arguments about history – particularly legal history – thrown around in public debate. And we need people to develop that knowledge and to guard against misuse of data.

If you had a time machine and could transport yourself to one point in the last 100 years which has made a huge impact on legal history, where would you go, and why?

It’s hard to pick only one moment – there are so many I’d like to see. It’s hard to beat the argument and decision of Brown v. Board of Education but maybe that’s too clichéd an answer. Karl Lewellyn is a real hero of mine and I’d like to meet him. Legal realism looms so large over basically everything we do in law in the United States. For personal and professional reasons, because the Selma to Montgomery march is so important in the US journey towards civil rights, I’d love to be there on a certain Sunday in March 1965. Those brave souls crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge to an uncertain future. And then, a few weeks later, they crossed the bridge again and went all the way to Montgomery, and the voting rights act of 1965 shortly thereafter.

Pick one or two salient points in the history of legal history that have changed the world as we know it.

There are some huge turning points in US history, for sure – I think of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Reconstruction era amendments to the Constitution, and the constellation of civil rights decisions and legislation that ran from just before Brown to the Fair Housing Act of 1968. Does it sound too jingoistic to say that the Declaration set us on the road to equality and we’ve been working out the promises of the Declaration ever since? A lot of recent writing on legal history focuses on the places where the United States has fallen short – far short – of that promise. But a lot of writing is about how we have moved towards that promise, too.

If a student was unsure about studying legal history, how would you convince them?

Students – particularly law students – should study legal history because so much of contemporary law relies on arguments from history. You learn a lot about what arguments are effective. Legal history, like law and economics, is a method that’s useful to lawyers and it’s a critical part of the profession. Studying legal history, we see how lawyers today are part of a very long tradition and it inspires us to carry on and improve on that tradition. Even those who are not going to be lawyers will benefit from studying legal history because arguments about the Constitution come up constantly in contemporary politics. As I’m writing this we are hearing about Donald Trump’s proposals about immigration; we have seen these issues before and legal historians have a lot to say that is relevant to Mr. Trump. Probably by the time you’re reading this, everyone will be talking about another constitutional controversy that is informed by legal history.

Featured image credit: The Obamas and the Bushes continue across the bridge. Official White House Photo by Lawrence Jackson. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How legal history shapes the present appeared first on OUPblog.

Why everyone loves I Love Dick

If, like most people these days, you take as much notice (perhaps more) of the books you don’t have time to read as the ones you are reading, you’ve probably heard of Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick. The book, a slow-burning cult classic since its first publication in 1997, has recently been the focus of renewed attention. In 2015, the novel was republished in a hardback edition, and had its first release in the UK. This sparked reviews and op-eds in The Guardian. Kraus—who writes lovingly of the New York scene of the 1980s—also finally received attention from The New Yorker last year. And it was just announced that the producer behind the hit-TV show Transparent will be adapting the book into a comedy series for Amazon Prime. (Good news for those who don’t have time to read everything.) How is it that a novel about a 39 year-old failed filmmaker in a sexless marriage has come to have such enduring influence and interest?

This recent recognition of Kraus’s unique voice is confirmation of something some of us have long known: Kraus writes powerfully about the experience of being a creative woman, and depicts with unflinching clarity the cruel patriarchal logic that has long worked to minimise the intellectual vivacity and originality of female artists and thinkers. I Love Dick’s enduring success and influence is due in part to the way it explains—to female and male readers—the positive and negative terminals of a woman’s creative life: the invigorating positive charge of inspiration, and the equally powerful negative charge of one’s place in the social order being apparently predetermined.

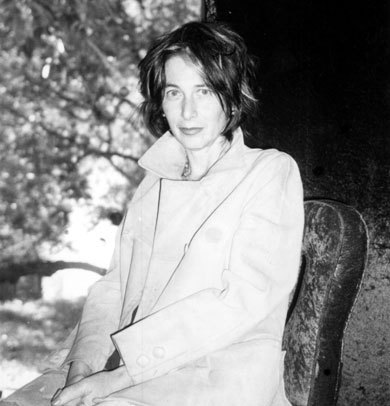

When I Love Dick was first released it was (infamously) reviewed in Art Forum as “a book not so much written as secreted.” In seeking to put Kraus in her place, the reviewer revealed his allegiance to the approach to women’s creativity explicated in the novel. As generations of feminist thinkers have demonstrated, the association of women with the private, the personal, the particular, and the corporeal (as opposed to the public, the objective, the universal, and the cognitive) has been a core element of the patriarchal logic that limits the cultural and political impact of women’s writing. This association has been strengthened by a tendency to read women’s writing as confessional, a genre which, despite its early promise, has long been thought to have a deleterious effect on society and culture. I Love Dick confronts and engages these logics head on. By taking the female central character’s crush on an influential male thinker as the engine for the plot, Kraus ingeniously locates her novel at the point where the tectonic plates of gender ideology and ideas about creativity meet. (The strategy is strengthened by Kraus’s use of the epistolary form: a genre associated with both the personal and the feminine.) Image credit: Photograph of author Chris Kraus by Semiotext(e). CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikipedia.

Image credit: Photograph of author Chris Kraus by Semiotext(e). CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikipedia.

While the novel’s central character, Chris, mines and explores the inspiration generated by her male muse (the ‘Dick’ of the title), she must also contend with the long history of the minimisation of women’s experience and their creative endeavours. She writes into a world she knows has little interest in what a woman has to say. Chris’s life (as it is told in the novel) is the humble edifice that unwittingly straddles these two underlying structures of contemporary culture; her marriage, her ambitions, her understanding of how culture is made and received, all start to shake when her creativity kicks into life after meeting Dick. The tremors soon connect Chris’s experiences with those of other artists and thinkers, such as the feminist artists of the 1970s (including Hannah Wilke), the author David Rattray, and lawyer and human rights activist Jennifer Harbury. The novel’s power comes from how it channels the seismic energy of inspiration and feminist critique: the creative and intellectual energy generated in Chris by the meeting with Dick is turned towards an unflinching exploration of why that energy will be minimised and dismissed: “Dear Dick,” Chris writes around the halfway point in the novel, “I’m wondering why every act that narrated female lived experience in the 70s has been read only as ‘collaborative’ and ‘feminist.’ The Zurich Dadaists worked together too but they were geniuses and they had names.”

While the novel explores the fraught reality of being female, it would be a serious error to think that I Love Dick is intellectual chick-lit. Kraus’s treatment of failure is pivotal. When the novel begins, Chris is in the post-production phase for her feature-length film Gravity & Grace. While receiving regular updates from the post-production crew in New Zealand, Chris is collecting rejection slips (in the forms of faxes, it is the mid-1990s after all) from the major and minor film festivals to which she has submitted the film. Before it is even completed, she is aware that the film is going nowhere because it will not be screened. In its treatment of failure, I Love Dick achieves that rare alchemy of great writing: a negative experience is depicted with such clarity, fullness, and ingenuity that one’s view on the subject is transformed. In an era when we are all expected to manage our lives and identities like brands, I Love Dick offers an unflinching but ultimately revelatory examination of what failure is and can do.

It is for this reason that I don’t share Eve Peyser’s concern that the adaptation of the novel “must tread carefully” because the work is “too rooted in Kraus’s interior life.” Such a reading redirects the energy of the novel back into the established circuit of viewing women’s writing as being, fundamentally, about the experience of an individual woman (the writer). If done sensitively, the adaptation may succeed in bringing much of Kraus’s biting humour and Chris’s wilful questioning to the screen. In doing so, a whole new audience might find the work as galvanising as generations of readers have over the last 19 years.

Headline image credit: Oxford Journals End-User Marketing team really do love I Love Dick by Alex Beaumont. Used with permission.

The post Why everyone loves I Love Dick appeared first on OUPblog.

Does climate change spell the end of fine wine?

Fine wine is an agricultural product with characteristics that make it especially sensitive to a changing climate. The quality and quantity of wine, and thus prices and revenues, are extremely sensitive to the weather where the grapes were grown. Depending on weather conditions, the prices for wines produced by the same winemaker from fruit grown on the same plot of land can vary by a factor of 20 or more from year to year. Similarly, prices for wines from the same grape type vary enormously, with wines from more conducive climates fetching a much higher price.

There is growing economic literature on viticulture and climate change. Numerous studies examine the relationship between weather and economic outcomes — such as wine prices and quality, prices for vineyard land, and winery revenue and profits for various wine growing regions and cultivars. Surprising to some, the evidence indicates that rising season temperatures can be either beneficial or detrimental to viticulture. This means there will be winners and losers from climate change. In general, the evidence suggests that wine growing regions located near the northern frontier of professional viticulture (e.g., Germany) — or the southern frontier in the southern hemisphere (e.g., Tasmania) — will benefit from further warming. Regions that are located closer to the equator (e.g., Spain or Greece) will be adversely affected.

Despite the progress that has been made in assessing the economic effects of climate change on wine and viticulture, there is still much to learn. First, many studies examine the effect of temperature changes, but do not account for the affect that future rainfall levels may have on grape growing. There is uncertainty about how rainfall levels affect grape growing. And there is also uncertainty about what changes in rainfall are likely to be associated with climate change.

However, the biggest problem with many analyses is that they do not consider the possibility of farmer adaptations to adverse climates. Instead many analysts assume a “dumb farmer” scenario. However, grape growers and winemakers have shown their adaptability to changing climatic and economic environments for thousands of years. As this photo of the Pundericher Marienberg Vineyard shows, German grape growers have adapted over the decades to cool climates by planting grapes to take advantage of the solar energy a properly designed panel can provide.

Image credit: Grape grower Clemens Busch works this steeply sloped Marienburg Vineyard despite the hazards because it’s solar-panel-like shape produces riper fruit and better wines. Courtesy of Weingut Clemens Busch, Pünderich/Mosel, Germany. Used with permission.

Image credit: Grape grower Clemens Busch works this steeply sloped Marienburg Vineyard despite the hazards because it’s solar-panel-like shape produces riper fruit and better wines. Courtesy of Weingut Clemens Busch, Pünderich/Mosel, Germany. Used with permission.In addition, earlier harvest dates, the rapidly increasing vineyard area in Canada and England, and the increasing plantings of red warm-climate varietals such as Merlot or Cabernet Sauvignon may be just three examples of current adaptations to a warming climate. Ignoring farmer adjustments, even if they are only partial, will overestimate the long-term costs of climate change.

Finally, climate change is likely to disproportionally affect grape growers and winemakers in European countries, such as France, that emphasize their location in their marketing rather than the grape varieties they grow, which inhibits various adaptations. Neither varietal nor regional substitutions can be easily achieved in these countries and in some cases are prohibited. This suggests that the notion of terroir wines, where a grape variety is expressed in terms of certain land and weather characteristics, may be too inflexible to allow for adaptations to a changing climate. Thus, unless the appellation rules in Europe are loosened and planting rights are abolished, this region will is likely to be one of the losers from climate change.

Featured image credit: purple grapes vineyard by jill111. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Does climate change spell the end of fine wine? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers