Oxford University Press's Blog, page 512

May 6, 2016

So long and thanks for all the tweets

Today is my last day editing the OUPblog. Back in January 2012, I took over as blog editor without so much as a handover (an early maternity leave prevented one). I promptly screwed up multiple things in the first few weeks, causing great annoyance to my colleagues. Then I gradually began steering the blog on a different course. By 2015, I could no longer read every blog post before it published, its success had outgrown the number of hours in my day. I’d like recount some of my highlights of my time here in the form of a gif essay:

We began drawing more heavily on authors and editors from journals, reference, monographs, professional titles, higher education, sheet music, and distribution clients — not just our trade titles.

We began editorial meetings to plan ahead, marking anniversaries or awareness days, or to discuss what’s in the news.

We wrote a lot about Word of the Year.

We lost one developer and gained a new one.

We oversaw a major redesign.

We faced down Chinese botnet attacks.

We welcomed six new columnists.

We celebrated our 10th anniversary.

We grew our traffic by 1000% (I know that sounds like a lie but I triple-checked).

My work at Oxford University Press has been wide-ranging, but the OUPblog has always been at the heart of it. Our tagline is “Academic Insights for the Thinking World”. I hope in my time here I have upheld that promise, whether with insightful essays on the Middle East, interviews with prominent cardiologists, or quizzes on “Which mythological character are you?”

Thank you to my predecessors Becca Ford and Lauren Appelwick who had such a fantastic vision for its future so many years ago and built the foundations that allowed me to grow it to what it is today.

Thank you to Kirsty Doole and Nicola Burton, the UK blog editors who helped guide and support me.

Thank you to all my deputy editors Julia Callaway, Dan Parker, Sonia Tsuruoka, Yasmin Coonjah, Elizabeth Furey, and Priscilla Yu.

Thank you to all our authors and contributors without whom we could not provide such phenomenal insight. Ed Zelinsky, Gordon Thompson, Mike Alvarez, Troy Reeves, Caitlin Tyler-Richards, Andrew Shaffer, Mark Peters, Melissa Mohr: it’s been a pleasure to work with you. Anatoly Liberman: I’m at a loss for words for my favorite etymologist.

And most of all, thank you to all the readers who have discovered us and returned throughout the years. I’ll be one in future.

Image Credits: (1) Longmont. by Jeremy Thomas. CC0 via Pixabay. (2) GIFs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, embedded via Giphy.

The post So long and thanks for all the tweets appeared first on OUPblog.

Skin cancer: What are the risks?

With bursts of sunshine starting to break through the relentless spring showers, the world is gearing up for summer. For a lot of us, that means getting away for a few weeks, and enjoying the glorious sunshine that the warmer weather brings. Unfortunately, basking in the summer sunshine isn’t without its risks. With Skin Cancer Awareness Month in full swing, we are focusing on the dangers associated with the most common type of cancer in the UK, the facts, current research – and crucially, ways you can prevent it.

The Facts

There is more than one type of skin cancer, but the skin cancer caused by the sun’s harmful UV rays is known as “malignant melanoma.” In fact, exposure to sunlight is the main environmental cause of melanoma. It is for this reason that melanomas are more likely to develop in sun exposed areas, such as the shoulders, back, and arms.

How do you know if you are at risk of developing skin cancer?

Some factors can increase your risk, for example, if you spent a lot of time in the sun as a child without UV protection, then you are more likely to develop melanoma later in life. In addition, histories of severe sunburn, exposure to UV radiation, or intense intermittent UV exposure are all associated with a risk of melanoma, which is why sunbeds and other artificial exposure to UV-A radiation should be avoided.

Image Credit: ‘Relax, Sunshine, Holidays’ by Unsplash. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Image Credit: ‘Relax, Sunshine, Holidays’ by Unsplash. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.There is also a genetic risk involved with melanoma. In fact, approximately 10% of cases will have a strong family history of melanoma. Darker moles, or benign pigmented naevi (to use the technical term), may be precursors and there is a general increased risk for individuals with these darker moles. Finally, your gender may mean an increased risk – in the UK, more women than men are diagnosed with malignant melanoma but death is more common in men.

Even when we know the facts, some self-proclaimed sun worshippers still put themselves at risk. Some don’t use sun screen, sunbathe at the height of the day, and take trips to the sunbed – all for the sake of that golden glow, made famous by the likes of bronzed beauties Jennifer Aniston and Gigi Hadid.

Screening

While curative treatment remains possible if melanoma is diagnosed early, prevention is always better than the cure. In a previous article, Ian Olver, author of The Cancer Prevention Manual, told us how we can avoid getting cancer, and, no surprises – taking precautions when in the sun was high on his list. In addition to avoiding the sun’s harmful rays, it is important to ensure you get checked and go for a screening, especially if you are at a high risk of developing skin cancer. As with other types of cancer, skin cancer can come back. In fact, up to 10% of patients diagnosed with melanoma will develop a second melanoma within five years of diagnosis.

You can also keep an eye out yourself, for any changes in your moles and marks – following the simple “ABCDE” method:

Asymmetry—one half different to the other

Borders—uneven, blurred, or scalloped

Colour—variety in the shade or colour

Diameter—usually, but not exclusively, >6mm

Image Credit: ‘Malignant Melanoma’, author unknown. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: ‘Malignant Melanoma’, author unknown. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Evolving—any change, sudden or continuous

Education, prevention, and further research

Initiatives to educate the public on skin cancer prevention have been wide and far reaching, the most well-known being the “slip, slop, slap” campaign, made famous by an Australian singing seagull from the 1980s. Australia has the highest incidence of skin cancer in the world and numbers are set to double, decade on decade. The Australian Cancer Council believes however, that its campaign played a key role in the dramatic shift in sun protection attitudes and behaviour over the past two decades.

Today, there are many alternative ways to get a suntan, rather than sunbathing and sunbeds. The increased popularity of the “fake bake”, and the wide range of products available, has encouraged people to use artificial tanning products in order to achieve that aforementioned “golden glow.”

In addition to education and prevention initiatives, cancer research is an ever evolving area, with new discoveries reported regularly. A promising new study, known as CheckMate, has found that a cocktail of drugs can eradicate traces of melanoma, even if the cancer has spread to other parts of the body. Though this combination of drugs has yet to be approved in the UK, these new findings are encouraging for oncologists and patients alike.

When you’re out in the sunshine this summer, remember to stay protected, and make sure you know the facts to reduce the risks.

Featured Image Credit: ‘Sand, Beach, Water’ by Unsplash. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Skin cancer: What are the risks? appeared first on OUPblog.

How the euro divides the union: economic adjustment and support for democracy in Europe

When the heads of European governments signed the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992, they laid the ground for Europe’s economic and monetary union (EMU) and, eventually, the introduction of the euro. Far from being merely an economic project, the common currency, so they hoped, would help pave the way towards a shared European identity. Today—almost a quarter century after Maastricht—that goal remains a distant prospect. On the contrary, during the economic crisis, European citizens in many respects seemed to have drifted apart.

In several Eurozone countries, the share of the population that is becoming ‘detached’ from its democratic political system (which we define as being unsatisfied with the way democracy works both domestically and in the European Union at large) has increased considerably between 2007 and 2013: from 27 to 74% in Greece, from 14 to 64% in Spain, and from 39 to 58% in Italy (according to Eurobarometer survey data). By contrast, the degree of democratic detachment has remained relatively stable in core Eurozone countries such as Germany.

Is there some causal connection between this cross-country divergence in support for democracy and the crisis of the common currency? To get to the bottom of this question, we need to study the causes of the crisis as well as the remaining policy options EMU governments have at their disposal when it comes to crisis response and resolution.

While the financial crisis of 2007/2008 had its epicentre in the United States, it soon affected Europe under the label of a “sovereign debt crisis.” Several analysts argue, however, that structural characteristics of the EMU provide a more accurate explanation of the crisis in Europe than a narrow focus on banking crises or public debt (pre-crisis debt ratios were low in Spain and Ireland, among others). They interpret the euro crisis as the outcome of national economies that were institutionally too heterogeneous, with very different wage and price dynamics, joined together in a monetary union that was clearly not an optimal currency area. In particular, monetary and fiscal policy instruments at the European level were insufficient to prevent and correct the sizeable competitiveness, and thus the balance-of-payments imbalances that had gradually accumulated during the first decade of the euro and now lay at the heart of the crisis.

Which options, then, remain for Eurozone countries struggling with recession, mass unemployment, and balance-of-payments deficits? Historically, the most common response to such situations has been currency devaluation. For the members of the Eurozone now sharing a common currency, however, this solution is no longer feasible. Additionally, traditional macroeconomic policy instruments, such as an accommodative fiscal or monetary policy, or an outright monetization of public debt, are either prohibited by the restrictive criteria enshrined in the Stability and Growth Pact – highly ineffective given the Eurozone’s fragmented capital markets – or simply lack political support.

The only remaining option for the crisis countries in the Eurozone’s periphery is to engineer an internal devaluation, i.e. to reduce sticky domestic wages and prices in order to re-gain international competitiveness and rekindle more export-led economic growth. This recessionary policy package, however, combining sizable fiscal consolidation programs with harsh welfare cutbacks and ambitious neoliberal reforms, carries considerable social costs (in the short- to medium-term at least). The acceptance of economic adjustment programmes among the general public is reduced further as a result of these policies being externally imposed on countries without leaving them a choice of feasible alternatives. The policies of internal devaluation therefore not only lack output legitimacy (in the sense of Lincoln’s government for the people), but input legitimacy (as government by and through the people) as well.

Arguably, this simultaneous loss of output and input legitimacy triggers the considerable rise in democratic detachment that we have seen. This explains why, in response to the imposition of economic adjustment programmes, satisfaction with democracy virtually collapsed in deficit countries such as Greece, Portugal, Spain, Ireland, Cyprus, and Italy, but remained relatively stable in the UK (which could resort to currency devaluation) or, despite some of the harshest consolidation measures seen in the crisis, Latvia (which abstained from currency devaluation and implemented an internal devaluation program voluntarily). Likewise, democratic support barely budged in countries such as Germany, Sweden, or Poland, where the economic crisis did not have any lasting negative impact.

The euro has not only driven the Eurozone apart economically during the first decade since its inception, but, more crucially, it also deprives countries of their most potent policy instruments for crisis response and resolution. Instead, it forces upon them a common response: the countries hit hardest by the crisis have no choice but to implement an extremely painful policy package of internal devaluation, combined with rigid austerity measures and far-reaching supply-side reforms. This has severe political consequences. Support for democracy has literally collapsed in the countries of the Eurozone periphery. It is the euro itself that divides the peoples of Europe in terms of their support for democratic politics.

A version of this article originally appeared on DeFacto.

Headline image credit: Euro sign frankfurt hesse germany by ArcCan CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post How the euro divides the union: economic adjustment and support for democracy in Europe appeared first on OUPblog.

It takes a whole child to raise a village

“When we get our story wrong, we get our future wrong,” David Korten wrote in Change the Story, Change the Future. If children are indeed our future, then the stories we use to educate and help them come of age are the most important stories to get right.

What was the story behind the proverb “It takes a whole village to raise a child”? There is an abundance of literature that strongly suggests that a whole village was probably performing rites of passage to collectively raise their children. Rites of passage were their shared story.

Today, rites of passage are often associated with mysterious, secret acts undertaken by drunken college students, gangs, secret societies, or other groups to welcome or “initiate” a member. Media reinforce this concept with headlines like “Bullying is not a rite of passage”; “Teens and Drugs: Rite of Passage or Recipe for Addiction?”; and “Fighting in Panama: The Implications; War: Bush’s Presidential Rite of Passage”. These rites focus on the individual and relate to perceptions of inclusion or exclusion from a group.

But there is another side to the story. Before rites of passage were ever construed as initiation of individuals, they were, in fact, community-organizing processes that villages engaged in for the purpose of community resiliency, adaptation, and survival. After all, community survival is contingent on children knowing and committing themselves to the values and practices that have allowed their village to exist across multiple generations.

So when we say, “it takes a whole village to raise a child,” I invite you to consider that it means it is the essential responsibility of the village to educate the young in the community lore that will allow successful continuity into the future. Collectively raising children strengthens community connections and social capital. Planning for our children focuses attention on future generations and the long-term consequences of our values and actions.

Raising children in ways that ensure the survival of our species for generations into the future is our most important work. We knew this eons ago and therefore did not simply leave it in the hands of individual parents and hope for the best. Instructing children through a rite of passage uses meaningful rituals that reinforce the shared values and beliefs of a community. This strengthens the community’s resiliency and ability to adapt, and renews its commitment to life-affirming values and behaviors.

When we get our story rite, we get our future right. Indeed, rites of passage have always been our shared story of community survival, yet this is a story we as a society seem to be forgetting. For over forty-five years I have explored and practiced this story of rites of passage as a community-organizing process. This ecological process that acknowledges and exploits the reciprocity between the individual and community facilitates youth and community development through rites of passage. This story includes guiding principles for organizing groups in ways that strengthen their commitment to collaborate in order to mutually solve problems and raise their children. It is a unifying story, built on a vision of hope rather than fear that can emerge from the creative imagination of a community and offer a bridge between western science and traditional wisdom.

The celebration of a rite of passage is renewing for the entire community. A child’s public expression of and commitment to a community’s values and beliefs reinforces expectations for behaviors for the survival of the entire community and health and well-being of all our relations. A child’s coming of age presents an opportunity for the whole community to examine, adapt, and re-commit themselves to their social and cultural heritage. In this light, it takes a whole child to raise a village.

Featured image credit: “Leaf” by Magnus Hagdorn, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post It takes a whole child to raise a village appeared first on OUPblog.

What exactly is ‘agriculture’?

Where I live, in the west of England, the lambs begin to appear in the fields in March and April. It’s a classic pastoral scene that must have been repeated across this landscape for at least the last thousand years, and in all probability for much longer. The only difference is that some of my local lambs and their mothers now have numbers sprayed on in blue paint, so that the farmer knows that lamb number 20 was born to ewe number 20, or that ewe number 68 had twins. I wonder if that spoils the pastoral image, which identifies the lamb as the embodiment of innocence and the shepherd’s life as the most enviable. ‘How sweet is the Shepherd’s sweet lot!’, wrote William Blake in 1789, in a pastoral tradition that could be traced back to classical Greece and still finds an echo in James Rebanks’s current best-selling The Shepherd’s Life.

In February, when the local ewes were heavy with their lambs, the newspapers carried an article about a Japanese company called Spread, based in Kyoto. In a fully-automated operation covering just over an acre the company plans to be producing 30,000 heads of lettuce per day by 2017, and more than ten times that number within five years. The company’s website calls it a ‘vegetable factory’; the Guardian (2 February 2016) called it ‘the world’s first fully automated farm’, pointing out that the seed planting will be done by people but everything else from watering to harvesting will be done by robots. So which is it, farm or factory? Where do we draw the line between farms and factories, or where do we set the boundaries of agriculture?

This isn’t a new question. Ruth Harrison raised it in 1964, when she published Animal Machines: the new factory farming industry, in which she expressed concern not only for the animals that were treated like machines within factory-like buildings, but also for the impact of those buildings on the rural landscape. In the half century since then agricultural technology has moved on, although you might not guess it from a cursory glance out of the train window. The fields are still green in the spring, or yellow with waving corn in the summer. But look more closely. You will not see many farms with a few pigs and chickens wandering around the farmyard, because they tend to be kept in bigger numbers, and often indoors. With the introduction of robot milking machines, the dairy cow may be the next animal to disappear from the fields, followed by the tractor driver, as computer-controlled tractors become more common. Agricultural technology does not stand still, and despite its image as a repository of traditional thinking and practice, farming has changed as rapidly as other economic activities in the developed countries, and more rapidly than many.

From time to time, from your train window, you will see several south-facing fields covered in photo-voltaic panels, generating electricity to feed into the grid. A recent edition of the oldest-established farm management pocketbook used by farmers and advisers has data not only for crops and livestock but also for five other forms of electricity generation, from anaerobic digesters to wind turbines. It also lists a wide variety of other activities carried out on farms, from fishing and clay pigeon shooting to horse riding, camping, motor sports and farm shops. Nearly a quarter of farms are letting out farm buildings to other businesses or cottages to tourists, and a DEFRA survey in 2008/9 found that just over half of farms in the UK were operating a ‘non-agricultural’ activity.

Which brings us back to the question: just what is an agricultural activity, and how does it differ from a non-agricultural activity? Is it about food production? In that case, the lettuce factory in Kyoto is a farm. Does it involve extensive land use? If so, producing chicken meat in sheds on just a few acres of concrete isn’t farming, while producing electricity from photo-voltaic panels or wind spread over fifty acres is. I’m fairly sure that most of us would agree about the sheep and their lambs safely grazing, blue numbers or not, being farming; beyond that … it’s worth thinking about.

Featured image credit: ‘Nature-landscape-field-agriculture’, by wobogre. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post What exactly is ‘agriculture’? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 5, 2016

Counterterrorism – Episode 34 – The Oxford Comment

What is counterterrorism? Although many studies have focused on terrorism and its causes, research on counterterrorism is less prevalent. This may be because the definition of terrorism itself has been heavily disputed, thus blurring the lines of what and who the targets of counterterrorism efforts should be. This brings us to a few questions: how has terrorism evolved and how has counterterrorism developed as a response?

In this month’s episode of the Oxford Comment, Sara Levine chats with Brian Lai, associate editor for Foreign Policy Analysis; Dr. Anthony Richards, author of Conceptualizing Terrorism; Richard English, author of Illusions of Terrorism and Counterterrorism; Erica Chenoweth, associate editor for Journal of Global Security Studies. Together, they explore the meaning of terrorism, whether terrorism can be used for more than just a political motive, and the effectiveness of violence versus non-violent counterterrorism tactics.

Featured image credit: Under the eyes of Marines and Iwakuni local officials, Yamaguchi Prefecture riot specialists board a vessel in search of armed terrorists as part of an annual bilateral training exercise at the Iwakuni Port Nov. 28. Image released by the United States Marine Corps with the ID 071129-M-1013R-001. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Counterterrorism – Episode 34 – The Oxford Comment appeared first on OUPblog.

Achieving the $1 trillion partnership: what does TPP mean for the US-India relationship?

Although India is not a signatory of the Trans Pacific Partnership agreement of 2015 (TPP), it should look at the document as a blueprint for the future of US-India relations. It includes all of the components that will drive the relationship – greater imports and exports, innovation, technology and more common regulations and policies.

TPP was a remarkably ambitious agreement. It estimates that, upon full implementation of TPP by all participating nations, 40% of the world’s economy will function more smoothly. And nearly 18,000 taxes and tariffs will be eliminated on products from technology to life sciences and manufacturing.

I believe that the United States and India can achieve a bilateral economic relationship that reaches $1 trillion by 2030. To do this, India will need to build the capabilities of its institutions in the private, civil and government sectors to achieve greater scale, create jobs and integrate better with the world economy. In addition, it will need innovation across sectors and business models to solve societal challenges and build Indian companies.

The TPP’s biggest impact is in these areas of innovation, intellectual property and new industries – exactly where the United States and India are headed for greatest collaboration – and competition. As a result, the two nations should look at TPP as the blueprint from which to negotiate bilateral agreements in the future.

The sector where TPP may most benefit innovators and entrepreneurs is clean energy and the environment. The agreement eliminates tariffs on environmentally-beneficial products and technologies, such as solar panels, wind turbines, wastewater treatment products, air pollution control mechanisms, as well as air and water quality monitors. Many of the TPP member’s countries had tariffs and other barriers in places in these sectors in the hopes of developing a domestic industry. With this agreement, the emphasis changes towards innovation and rapid adoption of clean technologies.

Intellectual property is the area where TPP has received the most scrutiny. It requires every member nation to crack down on counterfeit products – a boon to IP-dependent companies in technology, life sciences, manufacturing and energy. In addition, patents will, theoretically, proceed in multiple jurisdictions simultaneously – thus reducing the cost, time and uncertainty around patenting and IP recognition. These steps will greatly benefit startups based in the United States who are worried about IP protection and the costs of the patent process.

In the area of medicine, pharmaceuticals and public health, the agreement continues to be controversial. According to the White House, TPP “eliminates tariffs on medicines and medical devices, helping lower costs for hospitals, clinics, aid organizations, and consumers.” Medicines like amoxicillin, penicillin, and anti-malarial medicine, which are critical in the developing world, will remain available at lower cost, but perhaps only by the company holding its patent. TPP recognizes the Doha Declaration on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) and Public Health, which affirms the rights of countries to take measures to protect public health.

In other words, pharmaceutical companies and biotech startups will benefit from the recognition of common intellectual property norms. But if a nation, such as Vietnam, determines that a major local health concern requires the rapid distribution of low-cost, generic versions of medications, it maintains the right to do so. What remains unclear is whether or not it can source those medications from generic products, or must negotiate deals with the patent-holding pharmaceutical manufacturer. For startups developing orphan drugs or diagnostics for the developing world, this point will be critical to their success or failure. India will probably require similar safeguards in any IP policy.

One just needs to go back to 2014 to see that these two issues were, at the time, defining the US-India relationship. India’s policy to support local solar energy providers, and its intellectual property regime had put much of the US business community at odds with the Singh government.

The willingness of Vietnam, Peru, Brunei and Malaysia to join TPP also highlights a strategic change in how countries position themselves economically. By joining TPP, each country forfeits some of the benefits of being a low-wage, manufacturing economy. The agreement places strict limits on currency manipulation, protects collective bargaining for labor unions, requires acceptable labor laws around wages and working conditions, and protections for the environment. A particular emphasis was placed on the reduction of illegal logging, fishing or wildlife trafficking.

These countries are willing to lose their labor cost arbitrage advantage because of the much bigger advantages of being viewed as being a stable place to do business by the private sector. According to experts, the Vietnamese and others believe that the legal and operational familiarity bred by participation in the TPP will encourage more long-term investment than would have come through labor cost arbitrage. The desire of other emerging markets to join the TPP, including Thailand, Philippines and Indonesia, in the near future speaks to change in mindset.

And this is what I would expect to see from India. Over the next 10-15 years, as Indian industry matures, the two nations will have to negotiate bilateral agreements to address the exact same issues as TPP has done for economies that were already fairly integrated with each other. To expect India to jump in today is unfair. But to expect both nations to use the TPP as a blue print to get to a broader bilateral trade and investment treaty, is common sense.

Image credit: “Go Fisherman go – Gokarna India 2011” by Andreas Lehner, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Achieving the $1 trillion partnership: what does TPP mean for the US-India relationship? appeared first on OUPblog.

Reflecting on notable female historians, in celebration of Mother’s Day

A 2010 report by the American Historical Association showed that women comprised 35% of all history faculty, mirroring similar trends in gender disparity across academia. While the academic history field has traditionally been male-dominated, Mother’s Day serves as a day to celebrate significant women in our lives. In tribute to this year’s Mother’s Day, we wish to acknowledge and celebrate the many contributions by women to the field. Several OUP authors shared their thoughts on the female historians that have inspired them and shaped the field. Some are mentors and advisors that have supported careers, while others are admired for their work from afar. All are noteworthy for their contributions to the history field.

“My academic life changed in the fall of 2005. I had just started my PhD work at UC Davis when my advisor Kathy Olmsted–a brilliant historian in her own right–handed me a copy of Mary Dudziak’s Cold War Civil Rights and asked if I had read it. “Not yet.” I devoured it on the train ride home, amazed at the brilliant argument and the clean, beautiful writing. When Dudziak asserted that US government officials both embraced (and occasionally limited) civil rights reforms because of their concern over America’s image during the Cold War, I was amazed. Were there other times when domestic incidents during the Cold War impacted how other countries viewed the United States? The question led me to Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and productive research that led to my first book. I might not have asked the question if it hadn’t been for the thought-provoking work of the extraordinary Mary Dudziak.”—Lori Clune, author of Executing the Rosebergs: Death and Diplomacy in a Cold War World

“While she is rightfully known for her groundbreaking scholarship, Eileen Boris deserves equal recognition for her dedicated mentorship and commitment to forwarding conversations about US women’s and gender history and feminist studies at every possible turn. I was fortunate to find myself within Boris’s orbit during my graduate studies and I was quickly awed of her ability to balance dedicated activism, a prodigious scholarly output, and ample time for her students. Almost twenty years later, I still don’t know how Boris does it. But I do know that I am joined by many others who benefit from her close reading of work, incisive comments at conferences, ability to answer almost any question about the state of the field, and amiable company at the end of the day.” – Kristin Celello, co-editor of Domestic Tensions, National Anxieties: Global Perspectives on Marriage, Crisis, and Nation

“I am so lucky to count four female historians as my inspiration, including Eleanor Zelliot, Emily Rosenberg, Linda Gordon, and Elaine Tyler May. Given the tightness of space, I will highlight Eleanor Zelliot, the historian who got me started. Eleanor is a scholar of modern South Asia, with a special focus on pluralistic religious traditions in Maharashtra, as well as the Dalit movement. Eleanor’s scholarship excavates the spiritual and political lives of subaltern communities through interdisciplinary sources, including devotional songs, poetry, theater, and religious pilgrimages. The clarity and power of her writing pushes me to be accessible to a wide audience. On a personal note, Eleanor enthusiastically encouraged me to pursue a career as a historian—supporting my path at every turn, including my three-year hiatus between my undergraduate and graduate education as a flight attendant. She mentored me through a difficult entrée into graduate school when my initial advisor told me that it was “wonderful” that I was pursuing a Ph.D. in History because “as a wife and mother, you can write an article periodically while staying home and raising children.” A year later, Eleanor supported my move to American social and cultural history. When I was hired at UT-Austin as a newly minted Ph.D. with two babies in tow, Eleanor immediately got in touch with her friends there and told them to take care of me. And they did.”—Janet M. Davis, author of The Gospel of Kindness: Animal Welfare and the Making of Modern America

“I am inspired by Jill Lepore because of her smart, elegantly written essays and books. I was first fascinated by her 2006 New Yorker essay, “Plymouth Rocked: Of Pilgrims, Puritans, and Professors,” a layered examination of Samuel Eliot Morison’s career at Harvard, a brief history of the early years of the Plymouth plantation settlement, and an explanation of how journalists and historians approach their projects differently. This general approach is what makes all of Lepore’s work so interesting and vital—the way she presents the narrative intertwined with a meditation on how historians practice their craft. In 2013, I couldn’t put down her Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin, a creative biography that explores what written records do and do not reveal. Lepore’s most recent book, The Secret History of Wonder Woman traces the development of titular comic book character through the history of feminism while it explains how a historians tracks down and uses sources. Both books recover a hidden corner of history and present the work of a historian as every bit as exciting as a detective.”—Theresa Kaminski, author of Angels of the Underground: The American Women who Resisted the Japanese in the Philippines in World War II

“How to single out one female historian from such an endless and distinguished roster? Rather than turning to one that influenced me early in my career, let me note one more recently on the scene, writing with verve, researching with fervor, and taking chances. Ruth Scurr first caught my attention with her book, Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution (2006). Here was Robespierre rendered vivid and complex. Then, in 2015, Scurr published John Aubrey: My Own Life. The delicious irony is that Aubrey never published his own life or diary. What Scurr has achieved, with deft handling of many materials, is to capture Aubrey’s rhythm, voice, and knowledge. Scurr writes that the French Revolution “teems with life and burns with human, historical, intellectual, and literary interest.” The same may be said of her first two books.”—George Cotkin, author of Feast of Excess: A Cultural History of the New Sensibility

“Gerda Lerner. Her Creation of Patriarchy (1986) greatly influenced my thinking about the history of American librarianship, which has been dominated by women since the late 19th century. Shortly after the book was published I invited Gerda to give the Library History Round Table’s annual lecture at the American Library Association conference. As I rose to introduce her, I handed my copy of Patriarchy to my wife Shirl, seated immediately to Gerda’s left. “Would you like me to sign that?” Gerda asked. “Sure!” Shirl said, and handed her the copy. “To Shirley – for women’s emancipation,” Gerda wrote. Shirl still has the book.”—Wayne A. Wiegand, author of Part of Our Lives: A People’s History of the American Public Library

“UW-Madison history professor Gerda Lerner” by UW-Madison Archives via Wikipedia Creative Commons

“UW-Madison history professor Gerda Lerner” by UW-Madison Archives via Wikipedia Creative Commons“Amy Dru Stanley, professor of history at the University of Chicago and author of the now classic From Bondage to Contract: Wage Labor, Marriage, and the Market in the Age of Slave Emancipation, is an enduring source of inspiration. I regularly return to her penetrating scholarship on the moral conundrums spurred by slave emancipation and the rise of industrial capitalism for its deep historical insights as well as its compelling methodology. Ideas come first for Stanley, but her approach to intellectual history is neither top down nor bottom up. Rather, she works from the middle out, showing how ideas—richly debated and often fraught with paradox—connected former slaves, industrial workers, and other ordinary men and women with policymakers, high intellectuals, and other elites. This approach reflects Stanley’s abiding pragmatic historicism as well as her own ethical commitments to social democracy. To me, it shines as a model of how to explore the history of American democracy true to its varied participants and attentive to its manifold contradictions.”—Kyle G. Volk, author of Moral Minorities and the Making of American Democracy

“Kathleen Brown, my graduate advisor and professor of history at University of Pennsylvania, is the female historian who has inspired me the most. Kathy’s scholarship has been enormously important in early American and gender history. Perhaps more important for me than her scholarship, however, is her mentorship. She appreciates her students as whole people, not just academics. I feel incredibly fortunate to have had a scholar who so well combines a sharp intellect with warmth and compassion guide my academic journey and continue as my mentor.”—Cassandra A. Good, author of Founding Friendships: Friendships between Men and Women in the Early American Republic

“On the occasion of Mother’s Day, I can think of no better female historian to honor than my own Ph.D. advisor, Estelle Freedman. Imagining doctoral mentorship in genealogical terms is a commonplace, but Freedman is part of a pioneering generation of women scholars and scholars of women who challenged the notion that the male “Doktorvater” and his proverbial sons were the sole worthy holders of intellectual authority. Interestingly, given the occasion for this post, Freedman’s scholarship has been so powerful in part because she explores women as more than mothers: as sexual agents, as reformers, as political actors. Similarly, Freedman’s influence on the profession not only legitimized women’s history as a field, but within a generation also helped make that very designation feel narrow, as she has produced and inspired work on gender, feminism, and sexuality much more broadly. My generation of historians owes many intellectual and activist debts to Freedman and her colleagues, one of which is seeing blog posts like this both as progressive in highlighting the contributions of women and as problematic in that the term “female historian” (like “lady astronaut” and “girlboss”) assumes a normative male.”—Natalia Mehlman Petrzela, author of Classroom Wars: Language, Sex, and the Making of Modern Political Culture

“Three of my favorite historians are captivating writers and inspiring mentors – and great mothers. Their published works, their dedicated teaching, their service to the discipline and their outreach are models of what academic engagement with the world can and should be. They have served as role models for me personally and professionally. They each have wide, interdisciplinary interests, a good sense of humor and a gift for international friendship. Gabrielle Spiegel, Krieger-Eisenhower University Professor of History, Johns Hopkins University and former president of the American Historical Association writes on critical theory and the linguistic turn. Much of her work is highly specialized, but the questions she addresses and her humane approach are relevant far beyond the field. Olga Litvak, professor of History at Clark University and the author of Haskalah: The Romantic Movement in Judaism (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2012) is an invigorating and challenging interlocutor of eastern Europe and Modern Jewish history who asks me to think differently about things we all thought we knew. Miri Rubin, Professor of Medieval and Early Modern History at Queen Mary, University of London is a celebrated author with a wide popular following. Most recently she has published a translation from the Latin of Thomas of Monmouth’s Life and Passion of William of Norwich. This is the major source underlying my The Murder of William of Norwich: The Origins of the Blood Libel in Medieval Europe (OUP 2015). It is a pleasure to recommend her translation be read alongside my work to see what was said in the Middle Ages and then how it was interpreted.”—E.M. Rose, author of, The Murder of William Norwich: The Origins of the Blood Libel in Medieval Europe

“Mother’s Day—any day, really—is a perfect occasion to acknowledge and celebrate the work of women historians. Two of extraordinary accomplishment who deserve attention (and applause) are Barbara Tuchman and Margaret MacMillan. Both wrote books that expanded readers’ understanding of the origins and agonies of the Great War. Tuchman’s The Guns of August and The Proud Tower: A Portrait of the World Before the War, 1890-1944 helped stake out the territory back in the 1960s, and MacMillan’s more recent study, The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914, took the subject of the war’s beginning to previously unexplored regions of inquiry. In her case, she also produced a masterful account of the critical events that followed the fighting: Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World. Yet neither Tuchman nor MacMillan is a narrow specialist, confined to a single subject or period. Both have admirable range and tackle an array of topics and times. Tuchman, for instance, examined Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911-45; A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century; The March of Folly: From Troy to Vietnam, and The First Salute: A View of the American Revolution. In MacMillan’s case, she has published Women of the Raj, Nixon and Mao: The Week That Changed the World, and, most recently, History’s People: Personalities and the Past. Each, too, has stepped back from her specific historical studies at the moment to assess more general questions of their profession, with Tuchman collecting several of her essays in Practicing History and MacMillan developing a series of lectures into Dangerous Games: The Uses and Abuses of History. Besides their admirable scope, Tuchman and MacMillan are superb stylists who compose prose that animates people, events, and ideas in original and compelling ways. In their hands and through their words, the past vividly mirrors the times they’re describing and dramatizing. To say that future historians will learn lessons about their craft by closely reading Barbara Tuchman and Margaret MacMillan borders on understatement. Their work enhances the field and makes us see how we arrived where we are today.”—Robert Schmuhl, author of Ireland’s Exiled Children: America and the Easter Rising

Featured image credit: “Lisboa #05” by Nelson L. No known copyright restrictions. Via Flickr Creative Commons.

The post Reflecting on notable female historians, in celebration of Mother’s Day appeared first on OUPblog.

Yeats, Kipling, and ‘fin-de-siècle malaise’

‘I don’t like disparagement of the Nineties,’ W.B. Yeats told the Oxford classicist Maurice Bowra towards the end of his life. ‘People have built up an impression of a decadent period by remembering only, when they speak of the Nineties, a few writers who had tragic careers. They do this because those writers were confined within the period.’ But, as Yeats explained, those who survived the decade and ‘lived to maturity’ were the principal authors today. ‘The Nineties was in reality a period of very great vigour,’ he concluded, ‘thought and passion were breaking free from tradition.’

Among the ‘principal writers’ of whom he speaks, Yeats himself was probably the single most remarkable talent to have emerged from that creative interregnum when, as the suffragist Evelyn Sharp later remarked, every individual artist—male and female—was seeking to ride the crest of a great wave sweeping away the idols of a departing century. But for all his vindication of that formative decade, this statement was also yet another way for Yeats to subtly distance himself from the ‘lesser’ poets of his youth, the poets who wouldn’t get down from their stilts and walk open-eyed into the twentieth century—or who fell abruptly from those stilts, never to rise again. Arthur Symons, Lionel Johnson, John Davidson, the Rhymers’ Club. And not just these celebrated figures, but many more—journalists, activists, occultists, politicians—who briefly swam into Yeats’s constellation, or with whom he forged temporary alliances, before the two drifted, or broke, away. Though the 1890s has often been understood in terms of reaction, it is more useful I think to see it a period of fluid relations, a moment of pause and continuity: the turn of the century, upon which careers pivot and trends converge and ramify. There is much that might, with slight variation in circumstance, have turned out differently.

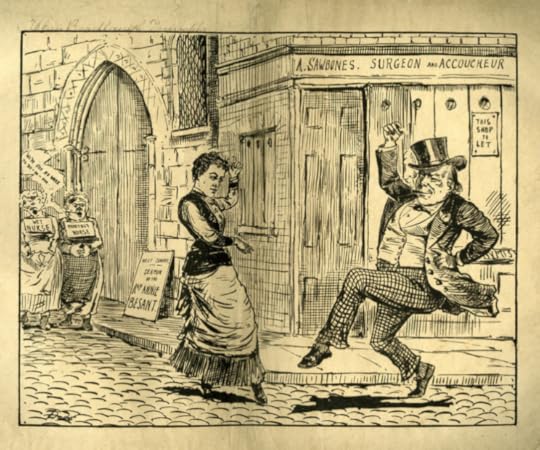

It’s this provisional and experimental nature of relations that I find particularly attractive. Politically the fin de siècle was a time of stagnant ferment, when strikes raged in the absence of a credible party of labour, when Irish Home Rule was held back by changes of government and energetic factionalism, and when two Indian MPs sat at Westminster (Dadabhai Naorojee and M.M. Bhownagree), but on opposite sides of the House. In the literary world, the horizon was filled by assorted cliques, communes, brotherhoods, and reviewing-mafias. No acknowledged laureate reigned, but many upcoming writers vied for the mantles of the recently-deceased Arnold, Browning, and Tennyson.

Image credit: An illustration of the era’s fluid relations: Annie Besant jigs mischievously alongside Charles Bradlaugh in 1888, with whom she campaigned for abortion rights. A mere two years later she had drifted away from the famous atheist–and the Fabian Society–in favour of a celebrated conversion to Theosophy. Courtesy Lilly Library, University of Indiana, Bloomington, Indiana. Used with permission.

Image credit: An illustration of the era’s fluid relations: Annie Besant jigs mischievously alongside Charles Bradlaugh in 1888, with whom she campaigned for abortion rights. A mere two years later she had drifted away from the famous atheist–and the Fabian Society–in favour of a celebrated conversion to Theosophy. Courtesy Lilly Library, University of Indiana, Bloomington, Indiana. Used with permission.And contrary to many accounts, factional boundaries were porous, with the more consummate networkers moving comfortably between the Rhymers’ Club, the Yellow Book group, and W.E. Henley’s “Regatta.” Reading habits too were notably catholic. A mixture of unfinished taste and craving for novelty gave rise to, among other phenomena that have interested me, the translations of Hafiz put out by the Irish MP Justin Huntly McCarthy, the fantasy stories of George Macdonald and Lord Dunsany, and the comparative study of global religions and mythologies carried on in such different quarters as James Frazer’s study and the Folklore Society. Moreover, in defiance of rather too binary readings of how gender and masculinity operated during ‘the Decadence’, there is a strong measure of overlap between aestheticist, and imperialist, postures. “Have you read Wee Willie Winkie?”, the quintessential Decadent Ernest Dowson wrote to a friend in 1890, the morning after a punishing absinthe binge, “I am going through a course of Kipling directly.” A “course of Kipling”: as though the Indian writer—cynical, amoral, insolent, and above all a strong voice against “the mob”, were strong medicine for some fin-de-siècle malaise.

2015 marked a number of 150th anniversaries. Such different writers as Arthur Symons and Sven Hedin were born in 1865, Kipling, Bernard Berenson, and above all Yeats, with H.G. Wells, Romain Rolland, Richard Le Gallienne, and Beatrix Potter following in 1866. In The Archaeology of Knowledge, Michel Foucault lends a conceptual clarity to such diverse groupings as these, proposing how our understandings might profit from the confusion and heterodoxy of a period, rather than prompting us to organize it into strands and subdivisions.

…so many authors who know or do not know one another, criticize one another, invalidate one another, pillage one another, meet without knowing it, and obstinately intersect their unique discourses in a web of which they are not the masters, of which they cannot see the whole.

This generation of writers seems to me particularly fitted to that sometimes overused Foucauldian term ‘constellation’: floating momentarily into creative alignment, before drifting apart again; inexplicably never meeting at all; some occasionally colliding with spectacular results—but more often impinging on one another obliquely, exercising the force of literary influence as one astral body agitates another through the distant tug of gravity. The fin de siècle continues to suggest new approaches, in various branches of cultural or historical study—wherever scholars feel a persistent, but creative, awkwardness as to what label or map to draw for a period that obsessively felt itself the fin of something, but knew not what, among many possible sequels, was then gathering its power to be born.

Featured image credit: Victorian Blackheath village London SE3 by Lloyd Rich. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Yeats, Kipling, and ‘fin-de-siècle malaise’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten facts about the sousaphone

Any American can recognize the opening notes of “Stars and Stripes Forever” and that most essential instrument of the American marching band — the sousaphone. How did this 30 pound beauty come to be? Despite its relative youth, the sousaphone has an extensive (and sometimes controversial) history.

The sousaphone is named after John Philip Sousa (1854-1932), who had early sousaphones made according to his specifications in the late nineteenth century.

Both the J.W. Pepper and C.G. Conn companies took credit for building the first sousaphone; while C.G. Conn claimed to have invented the instrument in 1898, Sousa recalled going to J.W. Pepper to create the first prototype in 1893.

Despite Pepper’s claim to the invention, it was the Conn sousaphone that eventually became the more commercially successful of the two, and even Sousa preferred it.

The sousaphone is similar to the tuba in many respects, but can be differentiated by its wide, flared bell and shape, encircling the player. Early sousaphones were built with bells pointed upright.

Upright sousaphones, called “rain-catchers”, never really gained popularity beyond Sousa’s use. Bell-forward sousaphones have been the college and marching band favorite since at least the 1920s.

Although primarily designed as a marching band instrument, the sousaphone also made a popular entry into jazz music in the 1920s.

Sousaphones are non-transposing brass instruments, most with three valves.

In order to make them lighter, Conn and the Selmer Co. began building sousaphones with fiberglass bodies, fittings and brass valves in the 1960s. In addition to being easier to carry, sousaphones are now harder to dent.

Similarly to upright band tubas, the sousaphone is pitched in E♭ and B♭. Some, however, have a fourth valve which lowers the pitch by a 4th.

The sousaphone was originally created for marching bands, but has recently become a popular instrument for street bands in Asia and Europe.

The above are only ten facts from the extensive entries in Grove Music Online. Did we leave out any fun facts about the sousaphone?

Featured image: “Sousafoon”. Photo by FaceMePLS. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Ten facts about the sousaphone appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers