Oxford University Press's Blog, page 510

May 12, 2016

A brief history of corpuscular discoveries [timeline]

Philosophers of science are in the business of explaining the special features of science, like the unifying power of scientific explanation and the wonderful sense of understanding it produces. We try to explain the amazing success of modern scientific theories, the structure of inductive inference in the science, and extract systematic positions – like realism, constructivism, and empiricism – from the evidence of theoretical success. One source of theoretical success I trace comes from the history of corpuscular alchemy and chemistry, which provided what we would now call atomic and molecular views of unobserved reality. Even the biological discoveries depicted here, like DNA and penicillin, rested on assumptions about molecular, and so corpuscular, structures. The vision of a world made up of atoms or corpuscles goes back at least as far as Democritus. Until the late 1500s, through Al-Kindi and Paracelsus and Gassendi that vision was heavily laden with magical incantation, spiritual fantasy, and errant theorizing. For most of that time, theorists wandered in darkness.

All that changed when practitioners in the late 1500s, on the cusp of modern materialism, ascribed accurate characterizations to a few of the most important dimensions of the corpuscles (their shape, their impact, etc.), so that unifying principles like Boyle’s law could be seen to apply to them. At least 80 years before Newton’s contributions, these trained practitioners in techniques of alchemy combined dissolving and reconstitution. This led them to the view that invisible particles were responsible for the change. Together with Galileo’s view, expressed in the Assayer, that most phenomena are produced by “matter in motion”, corpuscular alchemy and its progeny powered the steep ascent of science.

I have focused on theoretical advances – not merely instrumental or engineering improvements – in the areas of chemistry and physics, where evidence of an unobservable corpuscular world had real bite. There are lots of interesting and in some ways fruitful theoretical views that preceded atomic or corpuscular theories, those of Paracelsus, or the Islamic scientists, for example. But their theories were too inaccurate to drive sustained advances. Once thinkers got the right corpuscular hunch around the time of van Helmont, Sennert, and Boyle, chemistry and physics alike could take off. Lots of figures were atomists, but few of them until van Helmont, Sennert, and Boyle had distinctive experimental evidence for it. But it all arose from a contingent leap from late alchemy. The competing, and widely repeated story that science ascended from the scientific method may be comforting, but it is false.

Many philosophers, historians, and sociologists of science don’t like timelines, because they think timelines label early discoveries as primitive, and later discoveries as closer to our current, “elevated” state. These scholars often note that every epoch holds its views out as incontrovertible, or the highest state of accumulated wisdom, only to be proven false. Yet, it should also be noted that all of them are gratified that their doctors rely on chemistry rather than alchemy. Of course all of our current theoretical views fall short of the truth, but in accuracy and integration they differ from ancient and medieval theories on a scale that is orders of magnitude superior to predecessors. It is my goal to bring fresh resources to the defense of scientific realism, to document good explanations that we don’t understand, and to display the role of contingency in the history of science that allows a feeble view like corpuscular alchemy, by a series of unlikely events, lift a languishing or misguided field to a science worthy of the name. The timeline below is just a thin wedge of evidence showing that, in science, there is no substitute for being right, and that no amount of methodological effort can compensate for a bad theory. Instead, theoretical success occurred when contingent but truth-tracking events intervened.

Featured image credit: Large Hadron Collider. View of the LHC tunnel sector 3-4 by Maximilien Brice (CERN). CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A brief history of corpuscular discoveries [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

Come Together: Communities and divisions at Eurovision 2016

This week, the 61st Eurovision Song Contest, more affectionately Eurovision, will be broadcast to a global audience (including for the first-time a live telecast in the United States) with 42 countries competing in a series of semi-finals before the final, live show on 14 May. Established in 1956 as part of the then-fledgling European Broadcast Union, the contest has continued to grow in popularity and some would argue in cultural significance (Eurovision is the object of numerous scholarly works on spectacle, European identity, the nation-state, globalization – you name it). The contest has been rife with controversy in many years, often of a political nature, so much so that voting rules for this year’s contest has changed to reduce the influence of national “alliances” in favor of juries. Even with these changes, there are still some looming events that hang over this year’s broadcast, whose theme – “Come Together” –emphasizes the need for community.

Certainly, the attacks in Paris and Brussels, especially the former’s primary location being a concert, brought a sense of global solidarity in their wake and reinforced the notion of cultural solidarity in the face of terrorism. This year’s French entry – Amir’s “J’ai Cherche” – speaks to this notion of solidarity, as Amir himself grew up in the infamous French suburb Sarcelles in a Tunisian-Moroccan Jewish family. His song is a combination of French and English, the two official languages of the contest, and the words of this love song speak to the healing power of togetherness. Amir’s story and song symbolize the unity that Eurovision represents in many ways, and France is one of the favorites to win this year, which would be its first win since 1977, perhaps bolstered by sentiment.

France’s stiffest competition comes from Russia, which has excelled at the contest in recent years, including a victory in 2008. In the past few years, however, the contest has become a method of critiquing Russian domestic and foreign policies, most notably in 2014 when the Tolmachevy Sisters were booed. The Russian entry for 2016, Sergey, is currently another favorite to win Eurovision, but attention is being drawn to Ukraine’s entry, Jamala’s “1944.” The song chronicles the deportation of the Crimean Tartars during the Second World War and draws further attention to Russia’s recent Crimean adventure. Despite some critiques from Russian and Crimean politicians about the song, Eurovision asserted that the song does not constitute political speech and is within competition rules. Predictions have Jamala as a top-ten finisher but reception of the song will likely reflect to the continued contention concerning politics in the contest and how Eurovision attempts to define pop songs in a distinctive, commercial way.

Lastly, the British referendum on 23 June that will allow Britons to vote on whether to leave the European Union and the political and economic anxieties that the potential “Brexit” has engendered may play out in the contest. The British have long had an uneasy relationship with Eurovision characterized by a hostility that Karen Fricker has noted harmonizes with the broader Euroskepticism that defines elements of populist British politics. The UK most recently won in 1997 with an entry by Katrina and the Waves, whose biggest commercial success came 12 years earlier with “Walking on Sunshine”. Since then, the British have has several last place finishes but nevertheless continue to compete as part of the “Big Five” nations who automatically reach the Eurovision final. The broadcast of Eurovision in the UK was long accompanied by the commentary of Terry Wogan, whose wry and ironic take characterized a humorous and often distained reading of Eurovision as reflecting the very different values of Europe from the UK. This year’s UK attempt, Joe and Jake (two former contestants on the television show the Voice, which has become a place to find Eurovision contestants throughout the continent), were selected through a BBC show that allowed viewers to participate in the nominating process. The duo is projected to finish in the middle of the pack but will larger fears about a British exit generate sympathy points to convince the Brits to stay? The 2003 nul vote against the British influenced by the UK’s support of the Iraq War suggests that Eurovision viewers do have a political approach to the allegedly apolitical contest.

Even as the UK decides on its future relationship with the EU, its cultural influence continues to resonate in the Eurovision, as several of this year’s acts model their musical style on successful British artists such as Adele, Sam Smith, and Amy Winehouse in their quest for the Eurovision prize. Indeed, the English language has become in essence the lingua franca of Eurovision (even France’s entry capitulated a bit with its English-language chorus). Eurovision cannot imagine a Europe without Britain, but will the UK take Eurovision seriously to consider its place in the “New” Europe? If the spirit of inclusion that has become part of the pageantry of the song competition cannot convince its members to remain a part of it (NB: a country does not have to part of the European Union to compete), what “Europe” does Eurovision then symbolize?

Featured image credit: Eurovision Song Contest’s Greatest Hits, used with attribution to Thomas Hanses (EBU), Guy Levy / © BBC 2015

The post Come Together: Communities and divisions at Eurovision 2016 appeared first on OUPblog.

What makes your breakthrough useful?

News of amazing breakthroughs that can – maybe – help solve pressing societal problems in healthcare, energy, economic development, and other areas arrives daily. Yet problems persist, because breakthroughs become useful only if they are integrated with other aspects of the situation.

We hype physical breakthroughs in science and technology while ignoring the grunt work of bringing them into use. History puts making physical breakthroughs useful into perspective. In the late 19th century, modern industrial society arose around major physical breakthroughs in steam power, electricity, steel and chemicals, transportation, and mass production. But historians point out that it took major breakthroughs in social technologies to make these physical technologies useful according to Chandler in The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business (1977) and Pisano in “The Evolution of Science-Based Business: Innovating How We Innovate”, Industrial and Corporate Change (2010). Societies collectively developed new social technologies for figuring out entire operation systems, breaking these systems down into separate parts to be optimized separately, and scaling it all up. Societies also developed new social technologies for control with top down hierarchies of precise roles for legions of workers, defining clear goals, and identifying the most efficient means to achieve them. Clock-time social technologies like schedules and time and motion studies coordinated entire systems.

Economic problems in the early 21st century again require major breakthroughs in social technologies to put new physical technologies to use. According to Nelson in Technology Institutions and Economic Growth (2005):

Today, some of our most difficult problems involve developing the social technologies needed to make new physical technologies effective. Arguably the lion’s share of the strains in our health care systems are the result of advances in physical and medicinal technologies that societies have not yet learned how to manage or pay for.

However, nineteenth century social technologies can’t make 21st century physical breakthroughs useful. Current societal problems are complex, so innovators must discover all the parts and, more importantly, create the possible system that might integrate the parts to generate actual value. Managers cannot rely on top-down command and control or short term schedules, because possible solutions emerge unpredictably. Instead, managers must establish directions and boundaries to shape action, but continually tune the process based on emergent outcomes as these unfold.

Image credit: Windmills at the windmill farm Middelgrunden by Andreas Klinke Johannsen. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Windmills at the windmill farm Middelgrunden by Andreas Klinke Johannsen. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.I will outline three aspects of the 21st century social technologies that can make breakthroughs useful.

First, figure out what your breakthrough depends on to accomplish its potential. Twenty-first century problems do not come pre-packaged as a complete system that you plug your breakthrough into. You need to help create that new package. What other elements are central to your part’s functioning, how will your breakthrough interact with them to generate value, what might be the consequences, and how will you work with others to figure out these interdependencies? Inventors and scientists need not figure out the entire solution. But they can figure out some essential connections that would enable others to weave in their set of connections. Don’t push fragments, push workable sets. Public agencies, regional associations, and industry groups can enable the interweaving of various subsets.

Second, build on abductive reasoning. Nineteenth century deductive reasoning to confirm ideas presumes that theory is already fully developed, which is not the case for complex problems. Abductive reasoning formulates novel hypotheses about a complex problem, evaluates them, and reframes them in ongoing cycles of scientific discovery. People working on breakthroughs leverage the collective wisdom in their field by jointly hypothesizing configurations of interdependencies among elements of their problem that they think would lead to a resolution, empirically evaluating the hypothesized configurations to see what works and not, explore how and why, and reframing hypotheses through deliberation and reflection to accumulate learning.

Third, look more deeply and richly into the future. Imagine a variety of value creating opportunities that build on your breakthrough and others like it, and project the emergence of these various possibilities out a decade or more. Use this imagined portfolio as a guide to action (i.e., a strategy) as you cycle through the abductive learning routines for formulating, evaluating, and reframing configurations of interdependencies that would bring your breakthroughs into productive use. Mapping the future of, for example, curing cancer or building renewable energy systems requires that many agents and agencies participate. Together they generate a portfolio of value creating opportunities that provide stepping stones into the future. Intermediary results cycle back into abductive reasoning which helps to define core interdependencies for new breakthroughs.

Headline image credit: Open ideas by opensourceway. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What makes your breakthrough useful? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 11, 2016

Not a dog’s chance, or one more impenetrable etymology

Unlike tyke, bitch can boast of respectable ancestors, because its Old English form (bicce) has been recorded. The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology notes that bicce is obscurely related to Old Icelandic bikkja (the same meaning). The OED online never uses the phrase obscurely related, and this is a good thing, for this verbal formula, which so often occurred in the past, is itself obscure. As regards bitch, it must have meant that the complexes bicc-e and bikkj-a do not correspond to each other sound by sound (bicce has no j). However, let the presence of j in bikkja and its absence in bicce be the smallest of our worries. The English word’s shadowy congeners are also German Petze “bitch” and French biche, from Old French bisse “doe, hind.”

A hind and a bitch. Not related.

A hind and a bitch. Not related.Petze certainly resembles bitch. The sounds, designated by (t)ch in English and tz in German, are called affricates. In native words, they develop from simple stops: (t)ch usually goes back to k, and ts to t, so that once more we have an imperfect match, this time bik– versus pet-. The first consonant need not bother us: in German dialects, b and p alternate freely for the reasons that are of no consequence here. The i ~ e variation is common in the words of this type. But bisse should, most probably, be disregarded. According to the opinion of most modern Romance etymologists (and in this respect they differ from their predecessors), bisse goes back to Latin bēstia “animal” or rather its later popular form bīstia and has no ties to Germanic. I will assume that they know better, disregard the controversial moments, and only note that in dialects the French word sometimes means “grasshopper” (!), while in Old French it might perhaps also mean “snake.” The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology also mentions Saami pittja “bitch,” and “of bikkja there is a synonym grey/baka.” In greybaka it is of course baka that interests us. Bikke, bikkja, –baka and pittja are a poorly assorted pack, but, as we’ll see, it (not the pack but the impersonal it) will go from bad to worse.

This is the ash heap of history. Many old etymologies belong here.

This is the ash heap of history. Many old etymologies belong here.The old attempts to derive bitch from bite or from some Hebrew word can be relegated to what journalists call the ash heap of history. It is only worth observing that the story of bitch resembles that of tyke, the word discussed last week. We have seen that the same sound complex often designates “tyke” and “female goat” (German Ziege and others). Apparently, the meaning of the etymon, whatever its ultimate origin, was “female animal,” or “small animal,” with the concrete reference varying from dialect to dialect and from language to language. A look at the dialectal map of Germany shows that the meanings of Petze also vary along the familiar lines. Words like Bätzel (-el is a diminutive suffix) designate “lamb” and “calf.” Whether they have anything to do with Old Engl. bicce is unclear. A common German dialectal noun Batzen means “lump.” Not improbably, Bätzel “lamb, calf” developed from the meaning “something soft.” In English, the word for “animal” (such as German Tier) acquired the sense deer, for deer were the most often hunted animals. Is this why bēstia “beast” yielded French biche ~ bisse “doe”? But then there are “snake” and “grasshopper,” and this is most unusual.

We have pet– ~ bät– (that is, bet-) ~ bic-, as the basis of “bitch,” “calf,” and “lamb” (add to them bak-, the second element of greybaka) and then look around and discover that Dutch big means “pig.” The origin of both pig and big is “unknown,” though the safest dictionaries state with perhaps undue severity that big and pig are not related (no phonetic law will justify the variation b ~ p between Dutch and English). They never ask whether the English adjective big has anything to do with the animal name big ~ pig. Late Old Icelandic píka means “girl” and is supposedly a borrowing of Finnish piika, via Old Swedish, and of course we have not forgotten Saami pittja “bitch.” Some may wonder whether the eternal questions about the relations between Swedish pojke and Finnish pojke “boy” and their strong resemblance to Engl. boy has anything to do with our story. Indeed they do.

I have on many occasions mentioned the fact that the sound complex bag ~ bug ~ pak ~ puk, with endlessly varying consonants travel over half of Eurasia and turn up in such English words as puddle, pudding, bag, bug, bogey, Puck, bog, pig, Russian buka “bogeyman,” its synonym biaka (now a baby word), and dozens of others. They denote puffy, swollen objects, as well as objects capable of swelling and instilling fear. (Incidentally, in Native American languages, words like bi’ku “bitch,” with different vowels and b alternating with p, have also been recorded.) That many names for “small child” and “small animal” belong here can hardly be disputed. Female animals and their young are close neighbors. Is bitch a member of this fluid group? Perhaps. We suspect affinity but cannot prove it. As soon as we leave the Platonian shelter of the wall, that is, regular sound correspondences, we are thrown back to the age of medieval speculation.

While dealing with bitch, –baka, the second element of greybaka, is especially interesting. In bicce, the long consonant (cc) is typical of emphatic words, terms of endearment, nicknames, and pet names, so that bic (that is, bik-) and bak- are compatible in the same vague sense in which bag and bug are. I realize how crazy my next suggestion is, but does Russian sobaka “dog” (stress on the second syllable) contain the element –baka? Sobaka, a word little known in Slavic outside Russian, is a feminine noun, but it is the animal’s generic name. Russian words for “male dog” and “female dog” exist: kobel’ (stress on the second syllable) and suka, both of unknown or, let us say, disputable origin. Could sobaka be a blend of suka and the migratory baka, with su– becoming so-, under the influence of the extremely common prefix so- (as in the internationally known words so-iuz, so-viet, etc.)? Serious people will laugh me to scorn, and I’ll be the first to join in the laughter. But the origin of the obviously non-native sobaka has been searched far and wide, with practically no results. Why not shoot an arrow into the air?

It arouses astonishment that just bitch has become one of the most offensive words in the language; English is not an exception. All over the world, bitch means “whore,” and the phrase son of a bitch is universal. I’ll briefly touch on this question in my post on dog. But before that I have to say something about cubs. Here I would like to add only two small things. Swedish has the word årbigga “cantankerous woman.” Many sources state the –bigga is related to bitch and Icelandic bikkja. An excellent paper, written on this word a century ago, called this conclusion into question and did an excellent job of it. Finally, the English verb bicker is, most probably, not related to bitch. To bicker is distinct from to bitch. I mentioned this fact in my post on the history of bigot.

Featured Image: Dog by Savanna de los Santos, Public Domain via Pixabay. Images in text: (1) “She has a message!” by smerikal, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr. (2) “Doe grazing” by Alex Ristea, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr (3) “Čeština: Zbytek dřeva na ohništi” by Dezidor, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Not a dog’s chance, or one more impenetrable etymology appeared first on OUPblog.

The wellbeing of the nursing workforce

In an op-ed published in the New York Times titled “Why You Hate Work”, Schwartz and Porath highlighted Gallup data that revealed that only 30% of employees in the US and 13% across 142 countries feel engaged at work. Noting the high rate of burnout, they declared that for most of us, work is a depleting, dispiriting experience that is getting worse.

Within health care, stress and burnout are very significant issues. In an article published by the Journal of Organizational Behavior, Maslach et al. associate burnout, with a loss of enthusiasm for work, feelings of cynicism, and a low sense of personal accomplishment. Burnout is associated with early retirement, alcohol use, and suicidal ideation. A 2014 survey found that 68% of family physicians and 73% of internists would not chose the same specialty if they could start their careers anew. While the rate of burnout in nursing is not as high as in medicine, it is still significant. McHugh et al. found that 34% of hospital nurses and 37% of nursing home nurses report burnout.

Compassion fatigue, a related but distinct phenomenon, has recently emerged as a growing concern, particularly among nurses. Defined as the emotional residue or strain when exposed to suffering and repeated traumatic events, compassion fatigue has been linked to beliefs of the unfairness of life, feeling saturated by emotions, an inability to disconnect from work, and inability to accept support. While often accompanied by burnout, compassion fatigue emerges more suddenly and appears to affect a much greater proportion of nurses who bear witness to trauma on a daily basis without an opportunity for adequate resolution. Current literature suggests more than 80% of nursing staff will experience some degree of compassion fatigue during their career. Compassion fatigue has been associated with low morale, physical and emotional exhaustion, impaired job performance, absenteeism, and turnover. Some nurses who have left the profession prematurely described their departure as the only viable means to escape this unremitting stress.

As health care scrambles to respond to patient needs and fiscal realities, the concept of the triple aim has been introduced as a way to optimize performance. The focus of the triple aim is on improving the health of the population, improving patient experience, and reducing costs. Bodenheimer and Sinsky have proposed that the triple aim be expanded to a quadruple aim, adding the goal of improving the work life of health care providers, including clinicians and staff. Their point–care of the patient requires care of the provider. They make a strong case that chronic stress among the health care workforce threatens patient care and that organizations should be focusing on care team wellbeing.

Nurse administering a blood pressure exam. Public Domain via FreeStockPhotos.biz.

Nurse administering a blood pressure exam. Public Domain via FreeStockPhotos.biz.Nursing requires the delivery of humane, empathetic, culturally sensitive, proficient, and moral care in working environments with limited resources and increasing responsibilities. When nurses experience burnout or compassion fatigue, it impacts their personal wellbeing as well as the quality and efficacy of patient care. Nurses experiencing ongoing stress are more likely to eat poorly, smoke cigarettes, and abuse alcohol and drugs. Lack of self-care is a pervasive issue that adversely impacts personal health and wellbeing, patient care and the organization as a whole.

We believe that integrative nursing provides a set of principles and practices that focus on whole person and whole system care and healing that is transforming care across clinical settings and patient populations globally. Integrative nursing is relationship-based, person-centered, and focuses on improving the health and wellbeing of caregivers as well as those they serve. The principles of integrative nursing offer clear and specific guidance that can shape and impact patient care in all clinical settings and improve the health and wellbeing of nurses.

Human beings are whole systems inseparable from their environments.

Human beings have the capacity for health and wellbeing across all dimensions (body, mind, spirit).

Nature has healing and restorative properties that contribute to health and wellbeing.

Integrative nursing is patient-centered and relationship-based.

Integrative nursing is informed by evidence and uses the full range of therapeutic modalities, moving from least intensive and invasive to more, depending on the need.

Integrative nursing focuses on the health and wellbeing of caregivers as well as those they serve.

Recognizing the toll that chronic, unresolved stress and burnout has on nurses and the adverse impact on patient care, we are seeing more and more organizations looking for ways to increase the health, wellbeing, and resiliency of the staff. From respite rooms to stress reduction programs and wellbeing retreats, healthcare organizations are engaging nurses, physicians, therapists, and others to proactively identify and then address early symptoms that signal compassion fatigue and burnout. The American Nurses Association has recently launched the “Healthy Nurse, Healthy Workplace,” providing tips, tools, and techniques that support wellbeing and self-care across our profession.

As we celebrate Nursing Week, we invite you to take the time to invest in your own wellbeing, the most precious resource in health care today. As Janet Quinn reminds us, the journey to wellbeing begins with one degree of change. Ask yourself, “what is the one-degree change that I can make today that would bring me into a better relationships with myself?”

Featured Image: Nurse administering a vaccination. Public Domain via FreeStockPhotos.biz.

The post The wellbeing of the nursing workforce appeared first on OUPblog.

Why the EU would benefit from Brexit

The discussions about Brexit have centered around the question of whether it is in the national interest of the United Kingdom to remain in the EU or to leave it. It appears today that the British public is split about this question, so that the outcome of the referendum remains highly uncertain.

The question of whether it is in the interest of the EU that the UK remains a member of the union has been discussed much less intensely. The conventional wisdom in Brussels is that the answer to that question is positive. The UK should remain a member of the EU. A Brexit would be very harmful for the future of the European Union. But is that so?

I used to think that, indeed, it would be good for the EU if the UK remained a member. I have now come around and think that it would be better for the EU that the UK leaves the union.

There is a deep-seated hostility of the British media and large parts of the political elite against the European Union. This hostility has found its political expression in the Brexit movement. The proponents of Brexit cannot accept that the UK has lost sovereignty in many areas in which the EU has competences. They abhor the fact that Britain has to accept decisions taken in Brussels, even if it has opposed these. For the Brexit-camp there is only one ultimate objective: to return full sovereignty to Westminster.

Those who believe that a referendum will finally settle the issue have it wrong. Let us suppose that the Brexit-camp is defeated and the UK remains in the EU. That will not stop the hostility of those who have lost the referendum. It will not reduce their desire to bring back full sovereignty to the United Kingdom.

Having found out that they cannot leave the EU, the Brexit-camp will shift its strategy to achieve the objective of bringing back power to Westminster. It will be a Trojan horse strategy. This will imply working from within to undermine the union. It will be a strategy aiming at shrinking the area of decision making with majority rule and replacing it with an intergovernmental approach. The purpose of the British enemies of the EU will be a slow deconstruction of the union so as to achieve the objective of returning power to Westminster.

One may argue that having lost the referendum, the Brexit-camp will lose influence. That is far from certain. The agreement achieved by Cameron with the rest of the EU has not transferred a shred of sovereignty back to Westminster. This will be seen by the Brexit-camp as a huge failure, leading them to intensify their deconstruction strategy.

It is not in the interest of the EU to keep a country in the union that will continue to be hostile to “l’acquis communautaire”, and that will follow a strategy to further undermine it.

I therefore conclude that it will be better for the European Union that the Brexit-camp wins the referendum. When Britain is kept out of the EU it will no longer be able to undermine the EU’s construction. The EU will come out stronger.

I am not implying that without the UK the EU will find it easy to maintain cohesion. There are strong forces of disintegration at work in the Union mainly as a result of the Eurozone crisis and the more recent migration crisis. What I am arguing is that when the UK remains in the EU, its policy agenda, which consists of reducing the power of Brussels, will make it more difficult to overcome these challenges.

If Britain decides for Brexit it will be weakened, and will have to knock at the door of the EU to start negotiating a trade agreement. In the process it will have lost its bargaining chips. The EU will be able to impose a trade deal that will not be much different from what the UK has today as a member of the EU. At the same time it will have reduced the power of a country whose interest it is to undermine the cohesion of the union.

Featured image credit: Victoria Pier Flags (Hull) by Sheffield Tiger. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Why the EU would benefit from Brexit appeared first on OUPblog.

Mindful exercise and meditation for the aging

Global population is aging rapidly. Over the next four decades the number of individuals aged 60 years and older will nearly triple to more than 2 billion in 2050 (UN, 2013). With the aging of the population, the burden and cost of chronic disease will escalate worldwide. In order to ensure healthy and successful aging and reduce the cost of care for this huge increase, building resilience and wellbeing among the aging becomes a top priority for individuals, families, and society at large. Complementary and integrative medicine (CIM) is well positioned to offer interventions leading to prevention of major mental and physical diseases of aging and improve the quality of life for aging individuals and their families.

CIM therapies are defined by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) as “a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not generally considered a part of conventional medicine” (NCCIH-NIH, 2015). The most recent comprehensive assessment of CIM use in the United States found that roughly 40% of US adults had used at least one CIM therapy within the past year (2007), spending billions of dollars out-of-pocket on these therapies. The use of CIM for treatment of mood and anxiety disorders includes acupuncture, deep breathing exercises, massage therapy, meditation, naturopathy, and yoga. The most commonly used CIM health techniques in general population include prayer for health and the use of multivitamin supplementation. Given widespread use of integrative or mind-body medicine among our patients, there is an urgent need for greater awareness of the applications and outcomes of the commonly used mind-body interventions.

Mind-body medicine encompasses a number of techniques collectively known as mindful exercise (e.g. yoga, Qigong and Tai Chi), or meditation. Mindful physical exercise has become an increasingly utilized approach for improving psychological well-being and is defined as “physical exercise executed with a profound inwardly directed contemplative focus.” In general, mindful physical exercise contains the following key elements: (1) a non-competitive, non-judgmental meditative component, (2) mental focus on muscular movement and movement awareness combined with a low to moderate level of muscular activity, (3) centered breathing, (4) a focus on anatomic alignment (i.e., spine, trunk, and pelvis) and proper physical form, (5) energy-centric awareness of individual flow of intrinsic body energy, otherwise known as life force, prana, Chi, or Kundalini. The mindful exercise has been shown to provide an immediate source of relaxation and mental quiescence. Scientific evidence has shown that medical conditions such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance, depression, and anxiety disorders respond favorably to the mindful exercises.

‘Person Meditating’, by Spirit Fire. CC BY-2.0 via Flickr.

‘Person Meditating’, by Spirit Fire. CC BY-2.0 via Flickr.There is a growing database of the physiological effects of mindful exercise and meditation. Tai Chi and Qi Gong have been shown to promote relaxation and decrease sympathetic output, and to benefit anxiety, depression, blood pressure, and recovery from immune-mediated diseases. Both have been shown to improve immune function and vaccine-response. These practices have also been shown to increase blood levels of endorphins and baroreflex sensitivity, and to reduce levels of inflammatory markers (CRP), adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH), and cortisol, implicating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis as a mediator of stress and anxiety reduction.

Studies of meditation also report decreased sympathetic nervous activity and increased parasympathetic activity associated with decreased heart rate and blood pressure, decreased respiratory rate, and decreased oxygen metabolism. In our recently published study of Kundalini yoga compared to memory training in older adults with subjective memory complaints, we found that the yoga group demonstrated a significant improvement in depression and visuospatial memory compared to the memory training group. Both interventions improved verbal memory performance. Improved verbal memory performance was associated with increased connectivity between the language processing brain network. These findings point at the potential of using yoga to offset and delay cognitive decline, improve mood and coping with stress, and enhance brain plasticity.

Given the noninvasive nature of mindful exercise and meditation, recommending these exercises to all those interested in stress reduction and to patients with mental disorders generally seems an appropriate option for consumers and clinicians, particularly for conditions that have been studied in controlled studies. Some of these preventive techniques will include stress reduction that will enhance resilience to stress, and can improve cognition. Many of these techniques can be learned outside of the medical system and include exercise, lifestyle changes, mindfulness and mindful exercise, and the use of any joyful activities that can enhance the quality of life of older adults and their families. Ethical considerations should be taken into account when practicing or recommending spiritual interventions by healthcare professionals to respect patients’ beliefs in choosing mind-body interventions.

Featured image credit: Group of people practicing yoga, by Eli Christman. CC BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Mindful exercise and meditation for the aging appeared first on OUPblog.

May 10, 2016

Your new OUPblog editor

Alice Northover has been a phenomenal editor of the OUPblog ever since she took over in January 2012. She has overseen a major redesign, navigated us through a series of Chinese botnet attacks, and grown our traffic by more than 1000%. I have some very big shoes to fill.

The OUPblog celebrated its tenth anniversary last summer and has gone from strength to strength over the course of the last decade. In order to help the blog continue to flourish, our focus will be on expanding our community and growing our discipline specific content. Most of all, we will endeavor to inform and entertain you, the regular reader, as you are what makes the OUPblog so special.

I have been deputy editor of the OUPblog since 2014. Before becoming an editor, I was involved with the blog as both an avid reader and regular contributor from the Publicity department at Oxford University Press. Writing about children’s literature, tennis, and zombies was always a fun way to spend a Friday afternoon. My favourite thing about the OUPblog, both as an editor and a reader, is the diversity of content we publish. I can learn a new philosophical concept, a fact from American history, and a new word all in the same day. This is perfect for anyone who, like me, wants to sound like they know more about something than they actually do!

If you wanted to discover how to curry favour with me, or what I think about book-to-movie adaptations, you certainly can do. It won’t just be me looking after the articles on the OUPblog though. We still have Yasmin, Elizabeth, and Priscilla as our immensely talented deputy editors.

The OUPblog editorial team are going to miss Alice and we wish her every success for the future. We also appreciate the excellent work that Becca Ford, Lauren Appelwick, Kirsty Doole, and Nicola Burton did in getting the blog off the ground. Without Alice and the founding editors, the OUPblog would not be able to consistently deliver “academic insights for the thinking world”.

Featured image credit: Sun and leaves, by TMDaub. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Your new OUPblog editor appeared first on OUPblog.

Elderly addiction

Addiction is not a condition that springs to mind when we think of afflictions of the elderly, and yet it probably should be. Until now, alcohol or substance abuse among older patients has received relatively little attention, either as a clinical focus or as a research initiative. But we can no longer afford to neglect this growing cohort of affected individuals. Over the next decade, the number of individuals age 65 or older in the United States will swell from 40 million in 2010 to 55 million in 2020. By 2030, about a quarter of the population will be over the age of 60. This growth is due to increases in life expectancy and the aging of the baby-boomer generation, those born between 1946 and 1964. This cohort has had an unprecedented exposure to drugs and alcohol in their youth, due to cultural shifts in attitudes about substance use. As the baby-boomers age, they’re continuing to use these drugs at higher rates than previous cohorts did. Nearly one quarter of American older adults report using at least one psychoactive medication, and there will be an estimated 100% increase in medication misuse between 2001 and 2020 in this population.

There are many reasons why alcohol and substance use disorders (SUDs) in older individuals are generally misidentified and undertreated. To begin with, older individuals have historically been excluded from clinical trials, so recognizing signs of alcohol or substance abuse in this population relies upon extrapolating from patterns observed in younger cohorts. In addition, social stereotypes we hold about elders promote the false assumption that older adults do not suffer from SUDs. These beliefs serve to decrease suspicion by healthcare providers, who – even if they employ screening measures for alcohol and nicotine use – often neglect to screen for other substance use disorders. As family members and as providers, we carry unexamined biases that older adults do not use illicit drugs, or that they should be allowed to engage in whatever behaviors they choose at their age. Another challenge to accurate diagnosis is that older individuals, because of their reduced social responsibilities and retirement, show fewer of the behavioral disturbances or social “red flags” typically found in younger adults with addictions. In fact, DSM-5 criteria are difficult to apply to this population, as they lack sensitivity for older adults. Presentations may be atypical and resemble other medical or psychiatric disorders – and, indeed, older adults with alcohol or substance use disorders have high rates of concurrent medical and psychiatric disorders, with prevalence of up to 66% in some studies.

Photo credit: A nurse giving a middle-aged man a vaccination shot by CDC/Judy Schmidt acquired from Public Health Image Library. Public Domain via Freestockphotos.biz

Photo credit: A nurse giving a middle-aged man a vaccination shot by CDC/Judy Schmidt acquired from Public Health Image Library. Public Domain via Freestockphotos.bizWhat substances are older patients using and misusing? Alcohol and psychoactive medications are the classes of drugs most often implicated in substance use disorders in older individuals, and age-related metabolic changes increase their susceptibility to toxicity. Benzodiazepines are the most frequently prescribed drugs in the elderly for both insomnia and anxiety. Yet studies have shown that older patients disproportionately experience adverse events with benzodiazepines, such as falls and cognitive deficits. Similarly, opiate use in the elderly is rarely hidden, as these medications are generally obtained legally through physician prescriptions. While smoking rates tend to be lower in adults aged 65+ years than in the general population, this is unfortunately thought to be due to premature deaths from smoking-related causes. Approximately 14% of adults aged 65 years and older report using tobacco in the last 12 months. While legal substances such as alcohol and prescribed drugs are the drugs of choice for most older adults with addiction, cannabis is the most commonly used illicit drug in this population – and the number of older adults using cannabis is increasing.

Emerging research supports the benefits of developing and implementing elder-specific alcohol and substance treatment centers or tracks within general treatment programs. Such treatment interventions tailored to the needs of older individuals may include behavioral programs with a focus on the biological, psychological, and social aspects of aging; adjusting medications due to metabolic differences; or consideration of drug–drug interactions in light of the high prevalence of multiple medications (“polypharmacy”). Particularly relevant to older patients are cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) skills that take into account issues of memory impairment common in later life, as these may reduce patients’ ability to acquire positive coping skills. Recent research has found that motivational interviewing (MI) can be an effective treatment in older adults. Another important strategy for addressing late-life addiction is family therapy tailored to the needs of older adults (e.g., including adult children, spouses, or siblings). And finally, practitioners working with older adults may need to overcome specific treatment barriers such as medical comorbidity, ageism (i.e. addiction in an older patient may not inspire a sense of urgency to treat), reduced mobility, and transportation issues. When treatment is undertaken, it is important to integrate other relevant therapeutic issues such as loss, grief, isolation, or concerns about poor health.

More research needs to be done regarding evidence-based practices in recommended levels of use, identification, and treatment of hazardous and harmful alcohol use in older individuals. Age-related factors such as concomitant illness, changes in organ functioning, and medication interactions require specific considerations for appropriate prescribing of pharmacotherapy. Pharmacodynamics changes also mean that standard detoxification regimens may not be appropriate for older patients; they may need slower and longer tapers over weeks rather than days, to minimize rebound symptoms, withdrawal, and possible relapse. Above all, assessing and tailoring treatment to the patient’s individual risk factors in a nonjudgmental and collaborative way is the most important step in preventing harm from alcohol use in this population. We also need to better understand the risk factors and potential markers for addiction in later life. A number of risk factors for developing sedative misuse have been identified in older adults: social isolation, advanced age, female gender, receiving many prescriptions, and concurrent physical and mental illness. Older women appear particularly susceptible to late-onset SUDs because of genetic vulnerability or environmental stress, but they also tend to have better treatment outcomes than older men. Future research in the identification and management of addiction in later life should be a strong priority; it is “high time” we offered specific guidance on treatment interventions for clinicians working with older populations.

Featured Image: Temazepam 10mg tablets-1 by Adam from UK. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Elderly addiction appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten things you didn’t know about Argentine tango music

Tango is a multidimensional art form including music, dance, and poetry. It grew out of the confluence of cultures in the Río de la Plata region in South America and has since had over a century-long history. Here are ten things that you might not know about Argentine tango music.

1. A tango musician is a called a tanguero/a. Many tangueros/as are multifaceted musicians who compose, arrange, and/or perform tango music. In contrast, a tango dancer is called a milonguero/a, one who frequents the milongas (places where people dance tango).

Tangueros Lautaro Greco and Leopoldo Federico (left to right) playing the bandoneón at the 2011 Tango Festival, Buenos Aires, AR, photo taken by authors.

Tangueros Lautaro Greco and Leopoldo Federico (left to right) playing the bandoneón at the 2011 Tango Festival, Buenos Aires, AR, photo taken by authors.2. The bandoneón is tango’s signature instrument. It is a free-reed concertina that originated in Germany in the mid-nineteenth century as a portable organ in parish churches. It probably landed in Argentina on an immigrant ship around the turn of the twentieth century. Fiendishly difficult to play, the bandoneón has four rather illogically organized keyboard layouts. Each button creates a different pitch with opening and closing of the bellows. Listen here to the sounds of the legendary bandoneonist Aníbal Troilo (1914–1975) playing “Pa’ que bailen los muchachos” (“So That the Boys Dance”) in a 1962 recording with guitarist Roberto Grela.

3. The standard tango ensemble is the sexteto típico (typical/standard sextet). Early tango ensembles of the turn of the twentieth century often included flute, guitar, violin and bandoneón. In the 1920s, Julio De Caro (1899–1980) and his school established the standard sextet of two violins, two bandoneones, piano, and double bass. Listen here to a 1928 recording of the Sextet of Julio De Caro playing “Boedo” (referencing the neighborhood on the south side of Buenos Aires). From the 1930s to the 1950s, the standard sextet expanded to include an entire string section and a fila (line) of four more bandoenones. After the 1950s, tango ensembles reduced in size and often returned to new configurations inspired by the sexteto típico.

Julio De Caro Sextet, c. 1926–1928. Clockwise from left: Emilio De Caro, violin; Armando Blasco, bandoneón; Vicente Sciaretta, bass; Francisco De Caro, piano; Julio De Caro, violin-cornet; and Pedro Laurenz, bandoneón. Undated photo from the Archivo General de la Nación, Dpto. Doc. Fotográficos, Buenos Aires, Argentina, #71339_A. Used by permission.

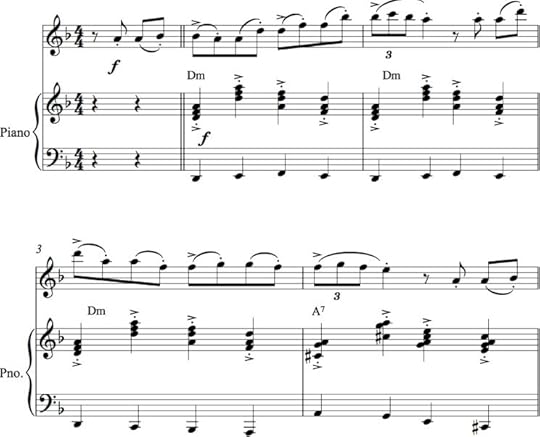

Julio De Caro Sextet, c. 1926–1928. Clockwise from left: Emilio De Caro, violin; Armando Blasco, bandoneón; Vicente Sciaretta, bass; Francisco De Caro, piano; Julio De Caro, violin-cornet; and Pedro Laurenz, bandoneón. Undated photo from the Archivo General de la Nación, Dpto. Doc. Fotográficos, Buenos Aires, Argentina, #71339_A. Used by permission.4. Tango has two distinct accompanimental rhythms: marcato and síncopa. The most basic marcato in four literally marks the beat. Síncopa is an off-beat pattern that includes a number of variations. See the notated examples of marcato and síncopa below.

“El choclo” by Ángel Villoldo (1861–1919), mm. 1-4, with marcato piano accompaniment arrangement.“El choclo” by Ángel Villoldo (1861–1919), mm. 1-4, with marcato piano accompaniment arrangement.

“El choclo” by Ángel Villoldo (1861–1919), mm. 1-4, with marcato piano accompaniment arrangement.“El choclo” by Ángel Villoldo (1861–1919), mm. 1-4, with marcato piano accompaniment arrangement.

Síncopa accompanimental rhythms.

Síncopa accompanimental rhythms.5. When playing tango melodies, tangueros often employ a technique called fraseo. Similar to “swing” in jazz, this flexible rhythmic interpretation of a tango melody often corresponds to the elastic ebb and flow of tango lyrics. Here Bolotin plays the melody “Tres esquinas” (“Three Corners”) by Ángel D’Agostino and Alfredo Attadía/Enrique Cadícamo first as notated, and then employing fraseo.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/03_45-Cantando-Fraseo_Bolotin.mp4

6. Tango yeites are perhaps the most elusive aspect of performing tango. Colloquially translated as “licks,” these extended techniques provide percussive effects to accentuate the rhythm. The Introduction to Damian Bolotin’s “Soniada” presents a veritable encyclopedia of string yeites.

7.Tangos frequently end with a flourish commonly called “chan-chan.” This cadential tag uses a V–I chord progression with scale steps 5–1 in the top line. The example below from the end of “Tres esquinas” illustrates this typical tango flourish.

“Tres esquinas,” arr. Stazo, ed. Wendland, mm. 79-82 with final cadence and “chan-chan.” Music: Ángel D’Agostino/Alfredo Attadía and Lyrics: Enrique Cadícamo © 1941 Ediciones Musicales Pampa (Warner/Chappell Music). Used by permission.

“Tres esquinas,” arr. Stazo, ed. Wendland, mm. 79-82 with final cadence and “chan-chan.” Music: Ángel D’Agostino/Alfredo Attadía and Lyrics: Enrique Cadícamo © 1941 Ediciones Musicales Pampa (Warner/Chappell Music). Used by permission.8. Pianist and bandleader Osvaldo Pugliese (1905–1995) ran a cooperative orchestra in the Golden Age. In this famous tanguero’s orchestra, each member contributed to the composing, arranging and performing of the works, and each member was paid accordingly. Here is an example of Pugliese and his 1952 orchestra playing his famous “La yumba” (named for the composers characteristic yumba rhythmic technique).

9. Bandoneonist and bandleader Astor Piazzolla (1921–1992) was not the only great post-Golden Age tanguero. Most people outside of Argentina cite Piazzolla’s name if asked to name a tango composer or musician. Yet, equally dynamic and innovative tangueros built on tango’s legacy and sustained long careers. Three such prominent tangueros include bandoneonist Leopoldo Federico (1927–2014), pianist and bandoneonist Julián Plaza (1928–2003), and pianist Horacio Salgán (b. 1916). Examples of Piazzolla’s works as well as those of Federico, Plaza, and Salgán include:

“Michelangelo 70” (named for the nightclub in San Telmo), Piazzolla, 1969

“Éramos tan jóvenes” (“We Were So Young”), Federico, 1986, performed by his quartet, 2010

“Danzarín” (“Dancer”), Plaza, 1958

“A fuego lento” (“On a Low Flame”), Salgán, 1951

10. Tango today is a living art form in Argentina. Some tangueros celebrate the past with renditions of tango standards like Villoldo’s “El choclo” and Gerardo Matos Rodríguez’s “La cumparsita.” Others push the art form into the future with new compositions, like Bolotin’s “Soniada,” Navarro’s “Contra todos los que rayen,” and Possetti’s “Dalo por hecho.” Here are links to these five tangos:

“El choclo” (“The Corn”), Villoldo, 1905, performed by Plaza’s Orchestra 1996

“La cumparsita” (“The Little Carnival March”), Matos Rodríguez, 1916, performed by Federico’s Orchestra, 1996

“Soniada” (play-on words from “soñar” [dreaming] and “Sonia” [the composers wife and musical partner]), Bolotin, performed by Cuerdas Pop-Temporaneas, 2006

“Contratodos los que rayen” (“Challenging everyone to defeat [him] on the double bass”) Navarro, 2013.

“Dalo por hecho” (“Consider It Done” or “It’s a Deal”), Possetti, 201

Featured image: “Juan Pablo Navarro and his orchestra at Almagro Tango Club, July 2014, Buenos Aires, AR”. Photo taken by authors.

The post Ten things you didn’t know about Argentine tango music appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers