Oxford University Press's Blog, page 511

May 10, 2016

Freedom of information lives on

The Freedom of Information Act is here to stay. At any rate for the time being. That is the good news implicit in the statement on 1 March 2016 by Matt Hancock, the UK Cabinet Office Minister, that, “this government is committed to making government more transparent”.

Mr. Hancock was welcoming the report of the influential Independent Commission on Freedom of Information, which included Jack Straw and Michael Howard among its members. The Minister’s statement and the report itself came as an enormous relief to users of the Freedom of Information Act who had feared that the freedom of information was as much in the Government’s sights as the beleaguered Human Rights Act.

The Government has accepted two key points made by the Commission. First there should be no upfront fee for requesting information. This is very important for, as the Minister said, the introduction of a new fee would have led to a reduction in the ability of those requesting information to make use of the Act. The second point relates to the ministerial veto on the disclosure of information. Both the Minister and the Commission agree that the Act intended the executive to have the final say as to whether information should be released. One of the questions the Commission considered was when a veto should be exercised. Could it be exercised after the courts had considered the matter?

Office workspace, by FirmBee. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Office workspace, by FirmBee. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.This question has to be considered against the scheme under the Act for appealing decisions on the release of information. If a request is refused the applicant can appeal to the Information Commissioner. There is a further general right of appeal to the First-tier Tribunal and from there a further right of appeal with permission on a point of law to the Upper Tribunal, the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court. The Government now accepts, in line with the Commission’s thinking, that it will only deploy the Ministerial veto on the disclosure of information after a decision by the Information Commissioner on whether the disclosure is in the public interest. The Commission was clear that the most appropriate veto was one that applied at the Information Commissioner stage. If this is right it means in practice that the Government has a choice, if it thinks the Commissioner has got it wrong, it can either appeal against the Information Commissioner’s decision or veto the disclosure of the information. If the veto is used it can only be challenged by way of judicial review.

The Government’s new approach is in line with the decision of the Supreme Court in the case about the disclosure of letters written by the Prince of Wales to Ministers. In that case the Court, which allowed the letters to be disclosed, also pointed out that there is no room for a veto under the parallel rules which apply to the disclosure of environmental information.

Campaigners for Freedom of Information cannot however afford to relax. The Government has not revealed its hand in respect of some other recommendations which the Commission made.

One of the questions put to the Commission was whether public authorities have the necessary space to think in private without falling foul of a freedom of information request. One of the exemptions to the right to information is in respect of government policy (section 35 of the Act). Did this give government enough protection? The Commission said: “yes, the exemption has afforded a significant degree of protection for sensitive information held by central government”. The Commission also thought, that the exemption could be improved by adopting the wording of a similar exception in the rules relating to the disclosure of environmental information. Many in Whitehall still think that freedom of information has a chilling effect on the discussion of the development of government policy. It would not be a surprise if in the future the Government returned to the question of what is a safe space for developing policy.

The Government has also said nothing about the Commission’s proposal to remove the right of appeal to the First-tier Tribunal against decisions of the Information Commissioner made in respect of the Act. This would simplify the appeal process and is what happens under the Scottish Act, but the removal of the right of appeal should be resisted. The Information Commissioner sometimes gets the facts wrong. There should be an opportunity to put this right.

Still the government is now on record as being “committed to supporting the Freedom of Information Act”. The optimistic view is that it will perhaps also have second thoughts about replacing the Human Rights Act with a British Bill of Rights. The European Convention on Human Rights is a “British Bill of Rights”. The drafting of the convention was overseen by the Conservative Sir David Maxwell Fyfe. It is based on rights which have long been recognized and upheld by the common law in contradistinction to the right of freedom of information which is new statutory right. Which of these long established human rights can safely be thrown away? A British Bill of Rights is a good sound bite. Perhaps that is its proper role.

Featured image credit: How to make a baby (out of paper), by moppet65535. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Freedom of information lives on appeared first on OUPblog.

May 9, 2016

Émile Zola and the Rougon-Macquart

Listen to, and read a transcript of an interview from Nicola Barranger for Oxford World’s Classics with Valerie Minogue, translator of Money by Émile Zola, part of the Rougon-Macquart cycle. In the interview, she introduces the Rougon-Macquart, Zola’s epic cycle of twenty novels.

Nicola Barranger: Why did Zola write the Rougon-Macquart series?

Valerie Minogue: Zola’s intention really was to do something like Balzac had done in ‘La Comédie humaine’. While Balzac had taken a sort of horizontal view of French society, and given a very broad panorama of that society, whereas Zola wanted to do it – if you like – in vertical terms going from one generation to another. Above all because he was tremendously interested in the effects of heredity, race, environment and moment in time. So you see history playing a large part in it and indeed historical events playing a large part and heredity yes, but you also see that heredity can also produce very different results

NB: There is a huge cast of characters for these twenty novels

VM: Huge, yes

NB: Was it always his intention to write quite so many novels when he started?

VM: I think he started off thinking that he would write about ten, but then the whole thing grew, and grew, and grew so he ended up with twenty novels. The reason why it is Les Rougon-Macquart is that there are two sides of this family. This is very much relevant to the whole question of heredity because you have the Macquart which are the illegitimate side of the family, which are the mostly rather poor, working class and all that. Then you have on the other hand the Rougon, who are the go-getters, the ambitious, mostly middle class even ministerial as in Eugène Rougon. So you have quite a divide really, on the Macquart side you get people like Gervaise in L’Assommoir, the laundress, which is the most wonderful novel, which tells her very sad life. And again her daughter Nana

NB: The very famous novel Nana,

VM: Yes so, on the other hand the Rougon you have Saccard, Eugène Rougon and Pascal Rougon.

NB: Was there a feeling that the social ills of the period that Zola was writing about, should be studied as much as the scientists would study hereditary disease?

VM: Absolutely, and Zola’s view was that however disgusting or even obscene, you must look at it closely, describe it accurately. It was important as if you were a doctor investigating a disease and the growth of the disease and all the symptoms of the disease. And then if you showed that properly, his view was that if you managed to show this effectively then somebody would do something about it, I mean the government, the people, would create a sort of grand swell if you like, of feeling. And indeed and quite to some extent he succeeded in that.

Featured image: Arbre généalogique des Rougon-Macquart annoté by Émile Zola CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Émile Zola and the Rougon-Macquart appeared first on OUPblog.

Sykes-Picot: the treaty that carved up the Middle East

The 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement has long been regarded as a watershed – a pivotal episode in the history of the Middle East with far-reaching implications for international law and politics. A product of intense diplomacy between Britain and France at the height of the First World War, this secret agreement was intended to pave the way for the final dissolution of Ottoman power in the region.

For centuries the Ottoman Empire had controlled most of southwestern Asia. To some extent, this was due to the dexterity of its diplomats and the temerity of its administrators. However, during the empire’s last decades, it was mainly due to the fact that Europe’s great powers typically regarded a weak but relatively stable Ottoman state as expedient – either to further their own interests or to bolster the continental balance of power.

By late 1915, roughly a year after Istanbul’s entry into the war as a Central Power, it had become clear to many in the West that the Great War had made the Ottoman Empire’s preservation all but impossible, at least in the far-flung and overstretched form in which it continued to exist. An agreement prepared by Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot in early 1916 was to settle the matter once and for all.

Pursuant to the text of the agreement, as well as the map that accompanied it, Britain was to exercise a considerable degree of formal authority over the areas around Baghdad, Basra, and Kuwait, as well as Haifa, Acre, and additional territory on the Persian Gulf. Other areas that would eventually find their way into Iraq and Saudi Arabia, as well as large swathes of what is now Jordan, would also fall within Britain’s sphere of influence. For its part, France was to enjoy formal authority over Lebanon, modern Syria’s Mediterranean coast, and vast tracts of what ultimately became southern, eastern, and southeastern Turkey. It would also project significant influence over the remainder of Syria and present-day Iraqi Kurdistan. Interestingly, an “international administration” was to be established for Palestine. Other clauses in the agreement concerned customs tariffs, the construction, ownership, and operation of railways, and the status of Haifa and Alexandretta (today’s Iskenderun) as “free ports” for France and Britain respectively.

Since the agreement spoke of “an independent Arab state or a confederation of Arab states” for areas not under formal British or French authority in addition to specifying areas in which London and Paris would “establish such direct or indirect administration or control as they desire,” the agreement has sometimes been deemed to be in nominal conformity with previous (and subsequent) pledges of autonomy and sovereignty to the Arab peoples of the Ottoman Empire. In reality, though, it was always understood that such “independence”, should it ever truly be granted, would be tightly circumscribed, and that much of the actual work of administration would be placed in the hands of European “advisors” and “functionaries.” After all, not only was the agreement prepared clandestinely, with no direct involvement on the part of Arab or other “local” officials, but it ran counter to promises of independence that had been made to Sharif Hussein bin Ali in return for Arab support of the Allied war effort against the Ottomans.

The agreement had been made with the knowledge and acquiescence of Russia, which, as a kind of incidental party, had also been promised power in Armenia and portions of northern Kurdistan. When the Bolsheviks overthrew the tsarist regime in late 1917, one of their first significant international acts was to publish the text of the agreement in Pravda and Izvestia. This went a long way to delegitimating the agreement. However, much of the underlying logic – placing predominantly Arab and Kurdish territories detached from the Ottoman Empire under British and French control – found expression in the League of Nations Mandates System. As Susan Pedersen has recently reminded us, the Mandates System blurred the (always porous) line between formal and informal domination, ensuring that most of the territories Sykes and Picot had discussed would be governed through a combination of foreign administration (Britain would administer Palestine, Mesopotamia, and Transjordan, while France would administer Syria and Lebanon) and international supervision (the League’s Permanent Mandates Commission would do most of the heavy lifting in this regard).

The deal that was struck in 1916 between Sykes and Picot – two men whose lives and careers are emblematic of a period in which European imperialism was undergoing significant internationalization and institutionalization – has been subject to extensive examination over the course of the past century. Indeed, arguably no other instrument prepared with a view to reconfiguring the law and politics of the Middle East has been ascribed the same kind of symbolic power.

For advocates of pan-Arabism, the agreement has always been an illustration of the hypocrisy of European policymaking – a sad reminder of the unity and prosperity that might have characterized the Arab world had the British and French kept their word and not had recourse to their usual divide-and-conquer tactics. If it wasn’t clear already, many now argue, the Syrian Civil War has made it all too apparent that some Arab states are little more than products of a colonialist imagination that knew remarkably little (and cared even less) about the forces and dynamics it sought to manipulate.

For many Palestinians, the 1917 Balfour Declaration, with its promise of a “national home” for the Jewish people, is the best possible evidence that whatever limited benefits may (or may not) have followed from “international administration” of the territory would never have precluded British support for Zionism. (Interestingly, Sykes appears to have been involved in fashioning the policy behind the Balfour Declaration.) More generally, willingness to partition the Middle East in accordance with fundamentally European concerns is viewed as a key reason for the creation of the State of Israel, the concomitant displacement of Palestinians, and the decades of conflict and occupation that have followed.

For Kurdish nationalists in Iraq, Turkey, Syria, and Iran, the agreement is one in a long series of legal instruments that have betrayed their national and international aspirations. Interestingly, it has also sometimes been understood to embody the sort of “statist” rationality against which Kurdish transnational movements, with their insistence upon complex confederal arrangements that criss-cross the Middle East’s artificial boundaries, have made a point of mobilizing.

For Islamists of various stripes, the “nation-states” that the Sykes-Picot Agreement eventually made possible, even inevitable, pose a direct and significant threat to the integrity and ideological primacy of the ummah, or “community of believers”. The so-called “Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant”, for instance, regularly denounces the agreement in line with its goal to redraw the map of the Middle East in one fell swoop – a goal that it seeks to realize through a combination of war, pillage, genocide, mass rape, and forced conversion.

The world today is to a significant degree the product of the fantasies and ambitions of Sykes, Picot, and countless other agents of empire. It is also the product of innumerable groups and individuals who have invoked the Sykes-Picot Agreement in order to secure recognition for their own projects. Far from being “dead”, as so many now claim, the agreement is more “alive” than ever. Zombie-like, it refuses to leave our midst, its grip on reality becoming more tenuous and surreal with every passing moment, the map it continues to offer us corresponding less and less adequately to the territory it was originally designed to reshape and represent.

Headline image credit: MPK1-426 Sykes Picot Agreement Map signed 8 May 1916 by Royal Geographical Society. UK National Archives. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Sykes-Picot: the treaty that carved up the Middle East appeared first on OUPblog.

State responses to cross-border displacement in South Asia

European countries are now experiencing an unprecedented influx of refugees from Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya. Europeans are trying to find out the causes of population displacement and measures to deal with the crises. Much can be learnt from the South Asian experience in dealing with the refugees. Over the last six decades cross-border displacement in this region has involved a dazzling array of different groups, from Assamese Muslims to Sindhi Hindus, from Tibetans to Burmese, from Sri Lankan Tamils to Afghans, and from Nepalis in Bhutan to Kashmiris in Nepal. Today, every South Asian metropolis is home to large communities of displaced people. For example, in Karachi, communities of Mohajirs (Partition immigrants from India) live side by side with later arrivals, mostly illegal, such as Burmese Rohingyas, Afghani Pashthuns, and Bihari Muslims. In Delhi, besides displaced Punjabis from Pakistan one can find Afghanis, Bangladeshis, Burmese, and Tibetans. Refugees and hosts are sharing the same urban space.

Mass exodus of refugees in the Indian subcontinent began at the time of Partition in 1947. Both Pakistan and India became prominent countries involved in sending and receiving refugees. Some 7 to 8 million Hindus and Sikhs arrived from West Pakistan to India and a little over 8 million displaced persons from East Pakistan sought asylum in eastern India between 1947 and 1971. The influx of Partition refugees in eastern India continued for a little over two decades. The crisis took a new turn when in 1971, some 10 million Bangladesh Liberation War refugees reached West Bengal, Tripura and Assam. Since then the flow has not stopped. In 1983, refugee crisis resurfaced, this time in the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu which became a sanctuary for displaced Tamils from Sri Lanka.

Three points merit attention in a study on refugees in India. First, the Partition of the country or the fragmentation of India’s colonial state structure at the moment of decolonization triggered large population movements. As the new states of Pakistan and India came into being out of the rubble of what had been British India and 500-odd princely states, millions of cross-border migrants were on the move. In some areas, for instance, Punjab, there was a swift, bloody and almost complete exchange of people. In other areas, for example, Bengal, displacement was a long-drawn process that stretched over decades and is still going on. Partition looms large over the study of displaced people in India. This is not only because of the unprecedented numbers involved but also because state formation and cross-border migration took place simultaneously.

The humanitarian approach in dealing with refugees in South Asia has set examples for the rest of the world.

Definitions of citizenship developed gradually and remained contested. This was particularly clear in the east, where the provinces of Bengal and Assam were bisected to form the new entities of West Bengal and Assam (India), and East Bengal (Pakistan). Here, it remained possible for years to define citizenship in terms of either religious community or territorial location. It was not until five years after decolonization that efforts were made to pin down people’s citizenship unequivocally. Passports and visas were introduced in 1952, giving territoriality the upper hand. But in this region of South Asia, citizenship continues to be negotiable to an unusual degree, as was demonstrated by the Indira-Mujib Pact of 1972 and the current discussions on ‘indigeneity’ in Assam.

Second, India is not a signatory to the major international agreements on displaced people, the United Nations Convention (1951) and the Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees (1967). By not signing these international agreements, India has retained certain autonomy in dealing with refugees. The state deals with the refugees on a case by case basis, by using certain provisions in the Indian Foreigner’s Act of 1946. As a result, the study of cross-border displacement in this part of the world is full of conceptual pitfalls. Definitions vary; while some groups of people who cross the border are welcomed as citizens joining the nation, others receive only state (and UNHCR) support as refugees, and yet others are treated as migrants without official residence or citizenship. Many stay as undesirable ‘illegal immigrants’ or ‘infiltrators’. The freedom that a non-signatory state enjoys in choosing a label that appears most convenient at the time of arrival not only landed displaced people in administrative quagmires but also hampered serious comparative research into cross-border displacement.

Finally, the treatment meted out to refugees in India has not been consistent. As the study shows, state responses to cross-border displacement have varied, both regarding different groups of displaced people and the same group over time. Many displaced people were ignored by the states in whose territory they found themselves, others remained on the receiving end of policies which covered the entire range from an occasional handout to rigorous institutionalization. Newcomers were often put into camps which might have been short-lived or of long duration. This study explains how the voices of the marginalized sections of the society, for example, the outcastes, tribes and urban poor, were muted in different ways, once they arrived in the country as refugees. But this is just one side of the story. On some occasions the Indian state upheld the principles of humanitarianism.

The humanitarian approach in dealing with refugees in South Asia has set examples for the rest of the world. Humanitarianism means an obligation on the part of the state to assist refugees, give asylum and look after relief and rehabilitation at any cost. The principal concern is to save human lives. As soon as the influx of refugees from East Pakistan began in April 1971, the Indian state offered assistance to refugees on humanitarian grounds. With the use of diplomacy along with humanitarian ideals, the state resolved an unprecedented crisis. India succeeded in conveying the message to the signatory states of UN Convention and Protocol that broader ideals of humanitarianism can be more effective in dealing with the refugees.

Featured image credit: UNHCR refugee hut, by Abel Kavanagh. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post State responses to cross-border displacement in South Asia appeared first on OUPblog.

May 8, 2016

Apology Round-Up: 2016 Presidential Race (so far)

It’s an election year and that means we get to think about the language of politicians—their vocabularies, vocal timbre, gestures, accents, metaphors, style, mistakes, and recoveries. I’m always on the lookout for interesting apologies, and the 2016 election has not been a disappointment.

Here’s a round-up of some apologies in the news from political figures running for president:

First, the Republican candidates:

In late February, after dropping out of the race, Jeb Bush told his financial backers in a conference call: “I’m sorry that it didn’t turn out the way that I intended.” His comments were reported as an apology, but it was really more of a lament. He’s sorry it didn’t work out, but he’s not apologizing.

Also in February, Marco Rubio was characterized as apologizing to his supporters for his weak debate and poor performance in the New Hampshire primary. Rubio said, “Our disappointment tonight is not on you — it’s on me.” Rubio takes responsibility here with the colloquial “It’s on me.” He added, “I did not do well on Saturday night. So listen to this: that will never happen again.” He’s taking responsibility and promising to do better, but not apologizing. And later, just before his home-state Florida primary, Rubio said he regretted his debate comments about the size of Donald Trump’s hands: “My kids were embarrassed by it, and if I had to do it again, I wouldn’t.” This too was characterized as an apology, but it is just a confession of bad behavior.

“Donald Trump” by Gage Skidmore, CC BY-SA 3.0 via WikiCommons

“Donald Trump” by Gage Skidmore, CC BY-SA 3.0 via WikiCommonsIn the same month, Ohio Governor John Kasich walked back comments he made about one of his early campaigns in the 1970s. He had told a crowd in Fairfax, Virginia that many women “left their kitchens to go out and go door-to-door and to put yard signs up for me.” When women supporters asked “WHAT!?,” Kasich first conceded that his comments were not made “artfully” and later offered this statement:

“I’m more than happy to say, ‘I’m sorry’ if I offended somebody out there, but it wasn’t intended to be offensive.”

Kasich is not apologizing; he’s just offering an insincere conditional.

Ted Cruz apologized for the action of misspeaking (but not for the claim itself) to then fellow candidate Ben Carson in February after a Cruz campaign surrogate had reported (on the evening of the Iowa caucuses) that Carson had dropped out. After being declared the Iowa winner, Cruz issued a statement saying “This was a mistake from our end, and for that I apologize to Dr. Carson.” As with Hillary Clinton’s apology, the first step is to characterize the offense (“a mistake”) and then add on “for that, I apologize.”

Cruz was less successful with his earlier apology to New Yorkers in January. After saying that Donald Trump represented New York values and that “everyone in the country knows exactly what New York values are,” Cruz was called on to apologize. Instead, he used the grammar of an apology to deliver an insult:

“Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton and Andrew Cuomo and Bill de Blasio have all demanded an apology, and I’m happy to apologize. I apologize to the millions of New Yorkers who have been let down by the liberal politicians in that state.”

As for Donald Trump, he seems to avoid apologizing more than any politician since Dick Cheney. Instead, he frequently demands apologies from others (from Ted Cruz, from FOX News, from Vincente Fox, from Hillary Clinton, from Megyn Kelly, from the New York Times). The closest he has come to an apology for anything is this statement, which he made some time after tweeting an unflattering picture of Cruz’s wife:

“If I had it to do again, I probably wouldn’t have sent it. I didn’t think it was particularly bad, but I probably wouldn’t have sent it.”

It’s more a casual afterthought than a real apology. The message seems to be denial: I didn’t do anything wrong, and I won’t do it again, maybe.

Now to some apologies by Democratic candidates:

In late 2015, Senator Bernie Sanders found himself needing to apologize for his campaign’s behavior when staffers were found to have accessed Hillary Clinton’s donor data. During the third Democratic debate last December, Sanders was asked by a journalist if he owed Clinton an apology. He said: “Yes, I apologize. Not only do I apologize, I want to apologize to my supporters. This is not the kind of campaign that we run.” The debate moderator had already framed what was being apologized for, so Sanders was able to be non-specific about the offense and use the apology to transcend the problem by asserting “This is not the kind of campaign we want to run.”

Transcending is one strategy; efficiency is another. In March, Hillary Clinton apologized after referring to Nancy Reagan as an advocate for AIDS research, angering AIDS activists and others. Clinton said:

“While the Reagans were strong advocates for stem cell research and finding a cure for Alzheimer’s disease, I misspoke about their record on HIV and AIDS. For that, I’m sorry.”

She first characterizes the offense (as misspeaking) and then uses the pronoun that to deemphasize the action and apologize: “For that, I’m sorry.” She used the same approach in her Facebook statement in September of 2015, apologizing for using her personal email for State department work:

“Yes, I should have used two email addresses, one for personal matters and one for my work at the State Department. Not doing so was a mistake. I’m sorry about it, and I take full responsibility.”

And that is how politicians apologize. Some laments, some responsibility taking, some regrets, some transcendence, some efficiency, an apology-as-insult, and a denial.

As your mother probably told you, in a good apology, you should name what you did wrong, apologize clearly and directly, take responsibility, and try to repair the harm.

Then there is real life, which often falls short.

Feature Image Credit: “Bernie Sanders for President” by Phil Roeder, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Apology Round-Up: 2016 Presidential Race (so far) appeared first on OUPblog.

Evangelicals, politics, and theocracy: a lesson from the English revolution

The current cycle of primary elections has re-ignited old debates about the place of religion in American political life. Those candidates identified as evangelicals, such as Ted Cruz, are often represented as proposing a top-down reconstruction of American society, encouraging a “moral minority” to take power in order to impose its expectations upon the culture at large. To the extent to which this is true – and the assumption can be contested – these candidates are developing some of the most controversial themes in modern evangelical thought.

This ambition to reform American culture shows the extent to which evangelical political thinking has changed. For much of the twentieth century, American evangelicals tended to disavow active political engagement, while praying for cultural reform. This political passivity began to change in the mid-1970s, when both candidates for the White House identified themselves as evangelicals, and especially after the early 1980s, when evangelical leaders began to build the ecumenical coalition that would drive conservative politics into the next decade. This change was informed by the publications and activities of a number of key figures, especially Frances Schaeffer, whose name is well known in histories of the Christian Right, and his less famous, but more controversial, fellow-traveler, R. J. Rushdoony.

The voluminous and demanding publications of Rushdoony did most to underwrite the new culture of evangelical engagement. In such publications as his massive Institutes of Biblical Law (1973), Rushdoony proposed a radical platform for political change. Developing themes latent in his Reformed and Presbyterian tradition, he denied the existence of natural law and argued instead that all government had to be reshaped according to biblical norms. At times that could sound innocuous. “God’s goal is a debt-free society which is also poverty-free,” he suggested. And he argued for lower tax, on the basis that governments should not claim a greater share of their citizen’s property than the tithe demanded by God. But Rushdoony understood that the godly society he imagined would only be made possible by a legal revolution.

Rushdoony argued that crimes – and their punishments – were to be defined by the Bible. That’s why he could consider alternatives to incarceration. Drawing on case law in the Pentateuch, he argued that crimes involving property should be resolved through restitution rather than imprisonment, but breaches of the first seven of the Ten Commandments – including idolatry, blasphemy, murder, adultery, and dishonoring one’s parents – should be punished by death. These positions may seem to be so extreme as to be irrelevant to the contemporary political climate, and Rushdoony’s name has not often been cited in this cycle of primaries, but when candidates propose a flat tax of 10%, or punishment for women who have undergone abortions, they are echoing his ideas. Whatever their similar goals, nevertheless, those evangelicals pursuing the top-down reformation of American society are overlooking Rushdoony’s warning about how these goals should be achieved.

Rushdoony’s hesitation about top-down reform is warranted by the results of a similar experiment in godly society that was attempted almost 400 years ago. In 1649, after a decade of civil war that began in Scotland before engulfing Ireland and England, a radical party of puritans and republicans within the Westminster parliament tried the king, Charles I, for treason. With the support of the army, they sought to re-form England, then Ireland and Scotland, into godly commonwealths. A raft of new legislation highlighted the kind of communities they sought to create: Christmas was banned, while adultery and other forms of sexual deviance were heavily penalized. The reformation was driven by new legislation and its effective implementation. And, by and large, it worked: the number of illegitimate births dropped to its lowest recorded value in English history. But this reformation, made possible by heavy-handed government, could not be sustained.

In 1660, after five hundred Sundays of compulsory church attendance, and too many years of taxation to support an increasingly unpopular military government, the fledgling puritan republic began to fall apart. As the political institutions of the republic crumbled, and as divisions appeared within its leadership, the army that had made the revolution possible brought it to an end. Charles II returned to London, and set about restoring the apparatus of his court. The old revolutionaries were hunted down, many of them suffering horrific and public deaths. When the remaining puritan clergy were ejected from the Church of England, in August 1662, very few of their parishioners went with them. John Owen, one of the most influential religious leaders of the period, had given much of his life to realize the world that the godly had imagined, but understood that the revolution had failed because its reforms had not been internalized: the revolution failed because too few people had been born again.

The end of the English revolution reminds evangelical political leaders to be alert to the limitations of top-down reform. Rushdoony understood that “the key to social renewal is individual regeneration,” for “man must be remade if the world itself is to be saved.” Human beings are not changed by politics alone. Perhaps, as the cycle of primaries continues, the most influential modern theorist of the requirements of biblical law may also become the most telling voice against its imposition.

Featured image credit: ‘Ted Cruz’ by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Evangelicals, politics, and theocracy: a lesson from the English revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

Should old-age social insurance be means-tested?

Almost everyone faces some risk of ending up old, sick, alone, and poor. The lengths of our lives are uncertain. Aging comes with increased chances of needing costly medical care. The loss of a spouse, often preceded by large medical bills, may leave one alone late in life. Absent a spouse or other family member to provide informal care, an expensive protracted stay in a nursing home may be needed due to dementia or disability. Women are particularly exposed to this risk. The picture below illustrates this point using data from the U.S. Health and Retirement Study. It shows how the distribution of retirees across health status, marital status, and gender changes with age. Notice that the two largest groups of 65-year-olds are healthy, married men and healthy, married women. However, the largest group of 95-year-olds is unhealthy, single women.

Demographic Structure of Elderly Population in the US by By Anton Braun, Karen A. Kopecky, and Tatyana Koreshkova. Used with permission.

Demographic Structure of Elderly Population in the US by By Anton Braun, Karen A. Kopecky, and Tatyana Koreshkova. Used with permission.This reality is one that all societies must face — how to deal with old, sick, and poor individuals who are alone and unable to improve their prospects by returning to work. Is there a role for governments to provide for these people? If yes, what does a good social insurance program look like?

The primary government insurance program for the elderly in the US and other OECD countries is usually a universal Social Security program. It is universal in that benefit eligibility does not depend on a person’s financial status. Many of these programs, such as US Social Security (formally known as the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Program) and the US Medicare health insurance program, are pay-as-you-go, meaning that benefits paid to current retirees are financed by taxes on current workers. Economists have struggled to show that such programs improve people’s welfare. Since these programs pay out benefits to all retirees, regardless of need, they tend to be large in size. US Social Security was 4.9% of US gross domestic product in 2013. They also tend to have large distortionary effects on incentives to save and work. The costs of these distortions in terms of reduced savings and labor are often so large that they outweigh the benefits from insurance the programs provide. In other words, the economics literature has, for the most part, found that people would prefer to live in a society without these programs.

It would be a mistake to conclude from these findings that there is no role for the government to provide social insurance for the elderly. US means-tested social insurance programs for retirees seem to be highly valued. Means-tested social insurance programs, in contrast to universal social insurance programs, are programs whose benefit eligibility depends on an individual’s financial situation. The largest means-tested social insurance program for US retirees is Medicaid. It pays for medical expenses that are not covered by Medicare. Medicaid is a particularly important program for US retirees in that it is the largest public funder of long-term care, including nursing home stays. Even though benefits are only provided to the poor, these programs are also valued by highly educated and more affluent households.

Why are means-tested programs for the elderly highly valued? They provide benefits to the people who need them most, when they need them most. For example, retirees can obtain Medicaid benefits if they either have low income and wealth or if they incur large, impoverishing medical expenses. These are exactly the situations in which such benefits are most valuable. Moreover, because they only provide benefits to those people most in need, these programs tend to be much smaller in size than universal social insurance programs, such as Social Security.

What does this mean for the future? The US and many other countries are starting to experience large and persistent increases in their old-age dependency ratios due to aging of the baby-boomers, increases in life-expectancy, and lower fertility rates. Higher old-age dependency ratios threaten the sustainability of pay-as-you-go social insurance programs because they place a large burden on workers. Ultimately, programs like US Social Security and Medicare will have to be reformed, and making these programs means-tested may help to improve welfare.

Featured image credit: hands aged elderly by Gaertringen. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Should old-age social insurance be means-tested? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 7, 2016

Tolstoy in art and on film

The portrait of Tolstoy currently on view at London’s National Portrait Gallery as part of the ‘Russia and the Arts: The Age of Tolstoy and Tchaikovsky‘ exhibition shows the writer sitting at his desk, pen in hand, head bowed. Only six years after Anna Karenina was first published as a complete novel, Tolstoy had already cast aside his career as a professional writer in favour of proselytizing his ethics-based brand of Christianity. Ge’s 1884 portrait is an act of religious devotion by one of the writer’s first acolytes. He portrays the Tolstoy dressed in black, his brow furrowed with concentration as he writes his first major tract, What I Believe, his mind clearly above such earthly and egotistical matters as posing and writing novels for commercial gain. Despite his new ascetic habits, Tolstoy never did quite become an anchorite. Another half dozen portraits would be completed over the course of the following three decades, including several by Ilya Repin, who reverently depicted his friend at the plough, in prayer, writing in spartan conditions, and sitting in lofty contemplation, like an Old Testament prophet.

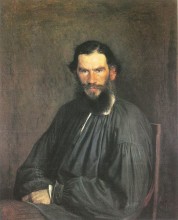

Ge’s canvas of 1884 provides a stark contrast to Kramskoy’s more famous portrait of 1873, painted when Tolstoy had just begun Anna Karenina. In that portrait, in which Count Tolstoy looks out at us imperiously in his peasant shirt, he is every bit the ‘great writer of the Russian land’, as Turgenev would later define him. As an aristocrat also prone to snobbery, Tolstoy had initially refused point blank to have his portrait painted for Pavel Tretyakov’s gallery (Tretyakov’s merchant class status explicitly denoted his involvement with money), but he gave in when the wily Kramskoy approached him personally at home in Yasnaya Polyana. And in the end Tolstoy was so stimulated by their ensuing conversations during the sittings that he created the character of the artist Mikhailov in Anna Karenina. This enabled him to introduce overt discussions in the novel about art, portraiture and the role of the artist, and, a more subliminal level explore the depiction, or rather objectification, of women. The portrait which Mikhailov paints of Anna is one of three separate paintings of her mentioned in the course of the novel, in which Tolstoy in compelling prose creates vivid portraits of diverse women from different walks of life to illustrate his exposition of their predicament in late nineteenth-century educated society.

Portrait of Leo Tolstoy by Ivan Nikolaevich Kramskoi. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Leo Tolstoy by Ivan Nikolaevich Kramskoi. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.In many ways, the directors who adapt works of literature for the screen are like portrait painters, in that they seek to present a coherent vision of a work of fiction in the concentrated space of a few hours’ viewing.From the beginning, pioneer film-makers wasted no time making screen versions of Tolstoy’s famous novels: cinematography was still in its infancy when the first adaptation of Anna Karenina was shown in 1911, only a year after Tolstoy’s death. Despite his calls for people to go back to a simple life of tilling the soil, Tolstoy was fascinated by technology, and was himself immortalized on celluloid on the occasion of his eightieth birthday in 1908 (although he was so famous by that time that many Russians remained convinced they were seeing an actor playing the great sage of Yasnaya Polyana). All the same, he would probably have taken a dim view of the twenty odd screen adaptations of Anna Karenina, not to mention the half dozen versions of War and Peace, which have followed.

Sergei Bondarchuk’s epic film of War and Peace (1966-1967) notwithstanding, it is the television adaptations of Tolstoy’s novels which have been the most successful, their more leisurely approach allowing for more chiaroscuro. There are many who still retain a great affection for the twenty-part series of War and Peace made by the BBC in 1972, but no doubt many more who share the view that the triumphant 2016 six-part BBC adaptation should have been much longer. The problem with cinematic adaptations of Tolstoy’s complex and richly-layered novels is that they run the risk of caricature. Feature films of Anna Karenina in particular have inevitably concentrated on Anna and Vronsky’s romance, at the expense of all the accompanying chapters designed to make us question the nature of relationships between men and women, while characters like the artist Mikhailov rarely even make it on to the drawing board. There is much to admire in Joe Wright’s spirited 2012 film, starring Keira Knightly and Jude Law, for example, but the very ambition to embrace so much of the novel produces mixed results.

Benedict Samuel and Sarah Snook in ‘The Beautiful Lie’. Image – ABCTV

Benedict Samuel and Sarah Snook in ‘The Beautiful Lie’. Image – ABCTVThe very best adaptations of Tolstoy’s fiction, whether for small or large screen, are those where the director has transposed the work into a quite different setting and time period. This is the case with Balabanov’s superlative 1996 film Prisoner of the Caucasus, in which Tolstoy’s 1870 short story of imperial Russian conquest is updated to the current-day war in Chechnya. It is the case with Bernard Rose’s film Ivans xtc (2000), which updates The Death of Ivan Ilych by recasting the central character (a searing performance by Danny Huston) as a Hollywood agent diagnosed with terminal cancer. And it is spectacularly the case with The Beautiful Lie, a six-part television adaption of Anna Karenina made by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation in 2015, directed by Glendyn Ivin and Peter Salmon. The brilliance of Alice Bell and Jonathan Gavin’s screenplay, which effortlessly transfers the complexities of marital dysfunction in aristocratic late imperial Russia to modern-day Melbourne, transforming Anna and Karenin into tennis celebrities, Vronsky into an indie record producer, Levin into a country vet, and his brother into an alcoholic, is matched by the sensitive acting of a peerless cast (including Sarah Snook, Benedict Samuel, Rodger Corser, Celia Pacquola, Sophie Lowe, Daniel Henhsall and Alexander England), and enhanced by a moving score. A typically heartwrenching scene has the tongue-tied Levin communicating his love for Kitty not with chalk on a card table, but with magnetic letters on a fridge. There are many other such deft touches as well as uncomfortable moments of truth which make us think continually of the novel, for once not in irritation at the liberties taken with Tolstoy’s text, but in wonder at the ingenious and perceptive ways in which it has been re-imagined, reinforcing its relevance to all our lives.

Featured image: Anna Karenina film poster. From the 2012 film starring Keira Knightly and directed by Joe Wright.

The post Tolstoy in art and on film appeared first on OUPblog.

Disguises and ‘bed-tricks’: Shakespeare’s love of deception [quiz]

Although Shakespeare employed disguises in many of his plays for the sake of comedic effect — take Sir Falstaff dressed as the obese aunt of Mistress Ford’s maid, for example — many more of his characters are entangled in other serious, deceptive plots. The majority of disguises are assumed with the sole purpose of concealing the individual’s true identity, many times for the assurance of his or her safety. In fact, most of Shakespeare’s plays address the concept of identity in one way or another. His comedies include great instances of disguise, mistaken identities, tricks, and revelations, which allows yet more characters’ identities to be restored and, ultimately, more lighthearted and amusing stories. However, his tragedies and histories involve more cases of banishment and disownment, where characters are stripped of their former identities. Whether dancing in masques or impersonating another, try out our quiz below to see if you recognize some of the disguises and deceptive plots from Shakespeare’s plays.

Featured Image: “Illustrations to Shakespeare – small rectangle series” by John Massey Wright. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Folger Shakespeare Library

The post Disguises and ‘bed-tricks’: Shakespeare’s love of deception [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the month: Thomas Hobbes

This May, the OUP Philosophy team honors Thomas Hobbes (April 5, 1588 – December 4, 1679) as their Philosopher of the Month. Hobbes is remembered as the author of one of the greatest of books on political philosophy ever written, Leviathan, in which he argued with a precision reached by few other thinkers. He was famously a cynic, holding that human action was motivated entirely by selfish concerns, notably fear of death.

Hobbes studied at Oxford and devoted his long life to private tutoring and study. In early life he traveled abroad as tutor to the Cavendish family, and in 1604, aware of signs of the impending English civil war, Hobbes moved to Paris where he could return to his writings in some security. After eleven years, Hobbes returned to England in late 1651, when his most famous book, Leviathan, had been published a few months earlier and was beginning to cause debate and to make enemies for its author.

Whatever the many merits of Hobbes’s other works, there is no doubt that Leviathan is his work of genius which guarantees his place as one of the intellectual giants of European philosophy. It is also one of the great works of English prose. In it Hobbes gives a highly original account of the nature of human beings and their psychology, and the nature and justification for government. According to Hobbes, there is no naturally given hierarchy among human beings, and therefore a perceived natural right to everything. In the absence of a controlling power, conflict will arise between human beings all seeking the best for themselves. It is only by voluntarily accepting articles of peace that humanity may be drawn to agreement. Each person must renounce their right to everything, and pass that right to a sovereign whose duty it is to use the common power of the community to enforce the law of nature for the benefit of all. It is this voluntary and rational renunciation that constitutes the contract of the people to accept one person as sovereign which creates the state.

There would be no restriction on the power exercised by the head of state, hence the name Leviathan, because to do so would imply that there was some other law by which his actions could be assessed, and this would imply another law-giver with power to enforce that other law. It is the function of the sovereign to rule in such a way as to maximize the amount of liberty that every person has, compatible with the security of the state. Despite debate over Hobbes’s view of human nature and the formation of a social contract when trust is at a minimum, Leviathan changed political philosophy in a fundamental way. There have been many interpretations of his work but few, if any, clear refutations of his analysis. Hobbes’s reputation as high today as it has ever been.

Featured image credit: Leviathan, by Thomas Hobbes; engraving by Abraham Bosse. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Philosopher of the month: Thomas Hobbes appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers