Oxford University Press's Blog, page 514

May 2, 2016

The Thatcherism of state-sponsored private sector retirement programs

With surprising speed, state-sponsored private sector retirement programs have assumed an important place in the nation’s public policy agenda. California, a pioneer in many trends, was a pioneer in this area also. The California Secure Choice Retirement Savings Trust Act, adopted in 2012, was the first law authorizing a state-sponsored retirement program for private sector employers, though the California act must be confirmed again by the Golden State’s legislature to take effect.

Illinois has also enacted its version of a state retirement plan for private sector employers. In the meanwhile, the US Department of Labor has proposed regulations encouraging such plans while other states follow California’s and Illinois’ leads. Recently, New York City Mayor Bill DeBlasio proposed that the Big Apple become the first municipality to sponsor a private sector retirement plan.

As debate about state-sponsored retirement plans has unfolded, that discussion has occurred along predictable lines. Advocates of such plans bemoan the low retirement savings rates of employees who work for smaller employers. Many small employers do not sponsor 401(k) or other retirement savings arrangements. These advocates contend that state-sponsored programs will encourage the (often low income) employees of small firms to save for retirement.

Opponents of state-sponsored retirement plans for private sector employers characterize such plans as an undesirable regulatory burden on small employers. Employers who do not maintain their own retirement savings plans will be required to enroll employees in the state-maintained plan and to give employees information about the state plan. Other critics argue that state-sponsored programs constitute unfair competition against commercial providers of retirement savings services.

Were Margaret Thatcher alive, she might have offered a different perspective from either of these. She might have welcomed state-sponsored retirement plans as encouraging low income individuals to invest in the stock market.

Margaret Thatcher would likely have been uncomfortable with a legally-imposed mandate requiring private sector employers to participate in a state-run pension plan. It is also likely that she would have preferred that the state not compete with commercial pension providers – though she might have been mollified by the prospect that part or all of these state programs will be outsourced to private firms.

However, Margaret Thatcher would probably have viewed state-sponsored private sector retirement plans as stimulating stock ownership by low income employees. This she would have strongly supported.

Among her most important achievements during her eleven years as Prime Minister was the devolution of important industries from government ownership. Among the iconic firms shifted to private ownership during Mrs. Thatcher’s tenure as Prime Minister were British Airways, Jaguar, and Rolls-Royce.

These firms, previously owned by the British government, were sold to the public, thereby transforming many British citizens into stock market investors. That transformation was a critical component of the Thatcher revolution which almost quadrupled the percentage of Britain’s adult population who were stockholders in traded firms.

Consider in this context the Illinois private sector retirement plan. As I recently noted in the Illinois Law Review, the Illinois program will establish a Roth IRA for each employee participating in the program. Each such IRA will be invested by the employee among several funds: “a conservative principal protection fund,” “a growth fund,” “a secure return fund,” and “an annuity fund.” If an Illinois employee does not select one or more of these funds for her IRA, “the default investment option” will be “a life-cycle fund with a target date based upon the age of the enrollee.” Such life-cycle funds invest heavily in common stocks when the employee is younger and become more conservative as the employee moves closer to retirement.

It is likely that many participants in the Illinois plan will be relatively low income individuals working for smaller employers. Through the Illinois retirement savings plan, many of these individuals will make their first entry into the stock market, either because they elect to invest their retirement savings in the “growth fund” or because they (deliberately or through inertia) invest in life-cycle funds oriented toward stock ownership.

Owning stock through an IRA or through an investment fund is not quite the same as holding directly the stock of a particular firm. Nevertheless, a state-sponsored retirement plan like the Illinois program will introduce many low-income employees to the stock market.

Margaret Thatcher would have approved this expansion of the “ownership society.”

Featured image: Retirement. (c) Olivier Le Moal via iStock.

The post The Thatcherism of state-sponsored private sector retirement programs appeared first on OUPblog.

Justice delayed, deferred, denied: Injustice at the Hague in the Karadžić and Šešelj verdicts

At the end of March–more than two decades after their crimes–the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) found Radovan Karadžić, chief political leader of the Bosnian Serb nationalists during the wars and genocide of 1992-1995, guilty of war crimes and sentenced him to 40 years. It could be said that justice was delayed and deferred, if not outright denied. While the 70-year-old Karadžić will probably never leave the (surprisingly comfortable) confines of The Hague’s UN Detention Unit, the verdict concluded that his forces had committed genocide in only one case: the July 2015 massacre of more than 8,000 Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) males in Srebrenica. The ICTY’s denial of genocide in other cases was greeted with dismay and indignation by Bosnians and others throughout the globe.

The following week, on 31 March, the ICTY’s reputation descended further, acquitting Vojislav Šešelj on three counts of crimes against humanity and six counts of war crimes. Šešelj was the leader of another ultra-right Bosnian Serb party, and like Karadžić, held various political offices and collaborated with military commanders such as Ratko Mladic to create a “Greater Serbia” at the expense of Bosniak and Croat populations. This map indicates the extent of their ambitions.

In an act of cultural genocide, Bosnian Serb forces directed led by Karadžić destroyed Sarajevo’s National and University Library (aka Vijećnica) during the 1425-day Siege of Sarajevo. The cello player in this 1992 photograph is Vedran Smailović, a Sarajevan who often performed at funerals during the lengthy siege. (Local musician Vedran Smailović plays in the partially destroyed Bosnia National Library during the war in 1992 in Sarajevo. Photo by Mikhail Evstafiev. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.)

In an act of cultural genocide, Bosnian Serb forces directed led by Karadžić destroyed Sarajevo’s National and University Library (aka Vijećnica) during the 1425-day Siege of Sarajevo. The cello player in this 1992 photograph is Vedran Smailović, a Sarajevan who often performed at funerals during the lengthy siege. (Local musician Vedran Smailović plays in the partially destroyed Bosnia National Library during the war in 1992 in Sarajevo. Photo by Mikhail Evstafiev. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.)UN secretary general Ban Ki-moon praised the Karadžić conviction as a “historic day” for international criminal justice. In a scathing commentary published two days later, British journalist Ed Vulliamy wrote, “I do not share this triumphalism, and take my cue from the survivors of Karadžić’s violence.” During the war, Vulliamy managed to cajole Karadžić into allowing him into the infamous Omarska camp, one of the more notorious and brutish of the hundreds of camps established by Serb forces. Vulliamy recalled the sight of “men, some skeletal, drilled across a Tarmac yard into a canteen where they gulped watery soup like famished dogs. The escorts bundled us out at gunpoint when we asked to enter the dark door from whence they had come – which turned out to be a factory of murder, torture and mutilation. Above the canteen, women were kept for systematic violation.” (Many Serb camps were established specifically for the purpose of systematic, mass rape.) Vulliamy bitterly observed that the ICTY’s verdict amounted to genocide-denial:

What happened in Višegrad on the river Drina, where thousands were butchered on a bridge, locked in houses and burned alive or kept in a rape camp was not genocide. What happened in the town of Foça where all Muslims were killed or expelled and another rape camp established was not genocide. What happened to the razed towns of Vlasenica, Bijeljina, Kljuć, Sanski Most, Brcko–I could go on–was not genocide. The total and systematic erasure of mosques, libraries, cultural and religious monuments across Bosnia was not genocide.

My city, Charlotte, is home to about 3,000 Bosniaks, and I have had the honor of working closely with this community. Mirsad Hadzikadic, Director of our university’s Complex Systems Institute, told me:

Giving a sentence of 40 years in prison to someone who participated in the development, overseeing, and brutal implementation of the idea of genocide will only come back to haunt those who influenced the reduction of the sentence from “life” to “40 years.” Subordinating moral values to practical, mundane, cynical politics will eventually undermine the societies that opted for such “pragmatization” of values. The corrosive effect of such moral compromises leaves societies defenseless against the barbarity of force.

Hamdija Custovic, Immediate Past President of the Congress of North American Bosniaks, asserted that, “when you talk about thousands of innocent civilians who were murdered and raped as a result of his command and orders,” 40 years is inadequate, regardless of Karadžić’s age. Custovic also pointed out that the travesties at The Hague are only one aspect of the betrayal of Bosnia and Herzegovina by “the West” from the early 1990s to the present:

It is also disappointing that he was not convicted of genocide in municipalities other than Srebrenica. At the same time, it is significant that he was convicted of 10 out of 11 charges, including the Srebrenica Genocide and Crimes against Humanity. The Hague Tribunal’s conclusion that the genocide in Srebrenica was orchestrated by the highest level of the so-called Republika Srpska government means that the legacy of what is now the RS entity in Bosnia and Herzegovina should be considered illegal and abolished.

The Republika Srpska or “Serb Republic” was carved out of Bosnia and given to Serb nationalists by the terms of the terms of the 1995 Dayton Agreements, thereby rewarding “ethnic cleansing.” The RS consumes half the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina; Karadžić served as its first president.

“This verdict,” concluded Custovic, “is an opportunity to make the case for abolishment of this modern day apartheid establishment in Bosnia and Herzegovina.” My friend was sadly unsurprised by the latest betrayals of Bosnia by the “international community.” As we approach the 21st anniversary of Srebrenica, it is worth remembering that this most infamous massacre was not inevitable, nor did the Yugoslav wars result from “age old hatreds” and intractable ethnic strife, as US news media ceaselessly argued at the time. Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist David Rohde summarized the betrayal by NATO and the UN of the people of Srebrenica:

The international community partially disarmed thousands of men, promised them they would be safeguarded and then delivered them to their sworn enemies…. The actions of the international community encouraged, aided, and emboldened the executioners. … The fall of Srebrenica did not have to happen. There is no need for thousands of skeletons to be strewn across eastern Bosnia. There is no need for thousands of Muslim children to be raised on stories of their fathers, grandfathers, uncles and brothers slaughtered by Serbs. (David Rohde, Endgame: The Betrayal and Fall of Srebrenica (New York: Penguin, 2012), 351, 353.)

July 11, 2010: New graves being dug on the fifteenth anniversary of the Srebrenica massacre. Not all the remains of the victims have yet been discovered. (Photo by Paul Katzenberger, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

July 11, 2010: New graves being dug on the fifteenth anniversary of the Srebrenica massacre. Not all the remains of the victims have yet been discovered. (Photo by Paul Katzenberger, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia CommonsThe post Justice delayed, deferred, denied: Injustice at the Hague in the Karadžić and Šešelj verdicts appeared first on OUPblog.

Between research and activism: The role of ‘organic intellectuals’

Once an activist, always an activist. This maxim seems to prevail even when one enters the world of research and academia, marked by its ostensible “objectivity” and “neutrality”. I started as an activist and ended up – for now at least – in academia. However, in my research experience, both through field visits as well as in the theoretical component of my current work, I don’t seem to let go of the activist constituent in me; that drive towards making a difference, even if it is on a small scale.

I have pondered many times whether and how the two worlds can merge in praxis exactly, if at all. Not only because in academia we are taught about the principles of “objectivity”, but more importantly because academia, inevitably, has a tendency to push one towards becoming an “armchair” researcher. This, at times, has instigated a feeling of being stripped away from the actual world one is trying to understand, analyze, and ultimately change, which in turn has led, occasionally, to a sense of skepticism not experienced during my years as an activist. Are the two spheres really so different from one another? Or do the theoretical and empirical components merge to form a praxis that is intended to improve the surrounding conditions?

Such reflections have led me to question the role of researchers as intellectuals, in particular during my field visits to Kabul, Afghanistan. Once in the field, many aspects I had read in methodology books to orient my research seemed to have become rather irrelevant. This is not to question the importance of a sound methodological design. But when one conducts research in a conflict/post-conflict context where, above all else, security concerns become the dominant paradigm, all that seems to matter is the safest way to get to a location where interviewees can be approached, questions can be asked, and answers can be obtained. Despite being a native researcher, equipped with a cultural, socio-political, and environmental compass, I nevertheless found it difficult to find my own position in all this. Where do I stand in relation to those I interview?

I have been researching transitional justice and war victims since 2008. I took a deep interest in this topic because of my own background. Like most Afghans, over decades of conflict I have lost close family members, and before coming to academia in 2005, I served as a full time activist to advocate for human rights and women’s rights in particular. This background has obviously left a deep mark on my engagement with academia, including on my own relationship with the war victims that I’ve been studying. Many questions have come up in relation to this, such as: What exactly is my role as a researcher, who knows the empirical reality of my case study so well? Is there a place for me to represent the victims I interview, and if so, through which means? Does the question of representation even matter in academia or is it something to be left only to the realm of activism? How do victims perceive me as someone who, on the one hand, shares and understands their pain and suffering, and, on the other, as a researcher ought to keep a distance, thus becoming the “other”? Such questions have been whirling in my head ever since I started my research, particularly as a PhD scholar.

What seems, however, to lend itself as a valuable lens through which to reconcile such incongruities is the Gramscian concept of “organic intellectual”. Gramsci, in one of his essays in the Prison Notebooks (written between 1929-1935), discusses the process of the formation of intellectuals and their roles in society. He defines traditional intellectuals as those who see themselves as autonomous and independent from the ruling social group, believing to stand for truth and reason. Organic intellectuals, on the other hand, emerge from and are tied to a social class within an economic structure. As such, they speak for the interests of a specific class or social group.

Gramsci’s proposition challenges the supposed “objectivity” and “neutrality” claimed to exist in academic work, and the argument to fit within the traditional model of intellectual activity. As we know, the academic world is predominantly Western ruled, often serving a particular social group or class. It is perhaps more candid to adopt Gramsci’s notion of the organic intellectual in our academic work, as has, arguably, been pursued by great thinkers such as Noam Chomsky, Edward Said, Mahmood Mamdani, Stanley Cohen, and many others who have challenged the dominant, traditional pattern. This approach, perhaps, can also bridge the gap between activism and academia. It provides a venue where scholars, like me, can engage with research in contexts and with people who have predominantly been studied and written upon by outsiders. This way, I see research as a commitment as well as a tool to challenge and change the status quo, as opposed to merely engaging with idealist notions in abstract.

Headline image credit: Kabul by Huma Saeed, used with permission.

The post Between research and activism: The role of ‘organic intellectuals’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Bookselling and the feminist past

The ‘disappearance’ of booksellers from Hong Kong in recent months reminds us that the free circulation of print can be very directly challenging to the powerful. Within social movements ranging across civil rights, disability, anti-apartheid, socialism, and anti-colonial nationalisms, books, print presses, and bookshops have been central to the movements’ intellectual development and comradeship. The women’s movement has had a similarly close relationship to print; bookshops, periodicals, and presses were a thriving presence within Edwardian women’s suffrage circles.

Bookshops took on a particularly significant role in the women’s liberation movement in the 1970s. The deliberately decentralised, anti-leader ethos of the movement could make it impersonal, or only open to those ‘in the know.’ The visible, accessible spaces provided by bookshops helped hold the movement together. Crucially, bookshops helped make feminism present to those outside the countercultural circles of communes and squats, or the privileged spaces of universities. Any woman could come and browse – and for those who feared the fierce radicalism of women’s centres and consciousness raising groups, this made feminism accessible.

Nonetheless, booksellers have not always been particularly well disposed towards women and feminism. I visited one particularly quirky bookshop recently that divided its stock bluntly into ‘women’ and ‘men’ – though it was unclear whether the category referred to author or reader. In Britain, even those bookshops that saw themselves as radical or ‘alternative’ had a tendency towards gender conservatism. Radical bookshop owners of the 1960s and 70s did not disguise their belief that women customers made frivolous requests, rather than displayed ‘serious’ political or intellectual concerns. Many bookshops were not welcoming to women with children. The countercultural bookshops such as Camden’s Compendium stocked pornography, despite protests from feminists. Where they did stock books on feminism, they tended to have a few token best sellers – Germaine Greer and Erica Jong – and even these were often displayed in the basement. Feminist theory, lesbian novels, and women-only periodicals were not found on their shelves.

Frustration with the book trade led to revolutionary strategies – women-only managing cooperatives staged takeovers of existing radical bookshops. Other women founded their own autonomous bookshops, including Sisterwrite in Islington (1978), Womanzone in Edinburgh (1983), and Silver Moon Women’s Bookshop on London’s Charing Cross Road (1984). At these bookshops, specialist and imported feminist and lesbian books shared the shelves with Virago novels, and books of feminist publishers such Onlywomen Press and The Women’s Press. Feminist bookshops brought new readerships and communities into being, and in doing so, shaped the women’s movement.

Image credit: Alternative cover to Susie Orbach’s ‘Fat is a Feminist Issue’, after feminist booksellers objected to the depiction of a woman on the original cover, from the collections of the Working Class Movement Library, Salford. Used with permission.

Image credit: Alternative cover to Susie Orbach’s ‘Fat is a Feminist Issue’, after feminist booksellers objected to the depiction of a woman on the original cover, from the collections of the Working Class Movement Library, Salford. Used with permission.Social and political networking within bookshops was as important as the books. Noticeboards offered news about gigs, meetings, and flatshares. Both Sisterwrite and Silver Moon provided women-only cafes, though somewhat bizarrely, Silver Moon were refused an alcohol licence for their café because of their lack of men’s toilets. The principle of women-only spaces was always contentious and hard to sustain. But the bookshops proved active in many additional ways, including refusing to stock books with sexist titles and covers, or selling such books with angry stickers or inserts. Feminist bookshops did not just serve an existing market – they challenged all aspects of their environment. Booksellers pioneered experiments with women-only spaces and developed activist techniques. Difficult decisions over which books to stock meant that booksellers were plunged into controversies over pornography, sado-masochistic practices, black feminism, and relations with men.

The flourishing of feminist bookshops was made possible by some factors unique to the 1970s and 80s. Public funding was available to buy stock and make rents affordable. Local government and Arts Council funds were key to the foundation of many of the radical and independent bookshops. Education and library budgets kept them financially afloat. The radical booksellers were also in contact with each other through the Federation of Radical Booksellers, which offered advice and support. When bookshops faced attacks, the Federation supported their legal battles. The attacks were varied – from arson and broken windows by far right and racist groups, to police raids and confiscation of stock. Gay and lesbian bookshops were particularly hard hit in the 1980s, when Customs and Excise mounted a campaign against books they regarded as indecent. From 1988, Section 28 of the Local Government Act prevented libraries and schools from buying books that ‘promoted homosexuality’, and budgets were withdrawn. Black bookshops were regularly firebombed. Feminist booksellers suffered abusive comments and violence from angry men. Radical bookselling was a stressful and low paid job, undertaken out of political commitment and in the teeth of substantial opposition.

It was not, however, the political opposition that destroyed most of the radical bookshops by the end of the 1990s. The growth of women’s sections in mainstream bookshops suggests a growing readership for feminist books. Instead, the transformation of bookselling away from independent booksellers was caused by the aggressive market strategies of the chain-owned bookshops, and the rising costs of retail rents and rates. Retail moved away from high streets, to out of town shopping malls. Most radical booksellers had always felt ambivalence towards the need to be profitable, and couldn’t or wouldn’t move. The nail in the coffin was the collapse of the Net Book Agreement in 1997. Books could now be sold at discounted prices. Supermarkets and American-owned chains such as Borders entered the market, and independent booksellers rapidly closed.

Today, some radical British bookshops such as Housmans, Bookmarks, Gays the Word and News from Nowhere survive. The last time I browsed in News from Nowhere, the fabulous women-run radical bookshop in central Liverpool, I chatted with the woman behind the till, tried on a t-shirt and bought a pamphlet on a whim. Radical bookselling can still enchant us. Yet despite the resurgence of interest in feminism and other radical politics in recent years, the distinctive world of feminist bookselling is largely over. The last dedicated feminist bookshop, Silver Moon, closed in 2001. Blogs and twitter accounts such as the F-Word and Everyday Sexism capture the vibrancy of feminist ideas and exchanges. But they offer no space for physical encounters, chance friendships, book recommendations, and for putting faces and a community to abstractions of feminist theory. Feminism came alive in bookshop spaces – and we are impoverished by the loss of feminist bookselling from British towns and cities.

Featured image credit: Silver Moon Women’s Bookshop by Jane Cholmeley, used with permission.

The post Bookselling and the feminist past appeared first on OUPblog.

Brexit and the World Trade Organization

As the debates regarding the UK’s referendum on membership of the European Union heat up, attention has turned to the possible consequences of Brexit. There are even consequences from a World Trade Organization (WTO) perspective, flagging up implications for UK sovereignty. The point made here is simple: contrary to the prevailing view, remaining in the WTO post-Brexit could entail a greater threat to UK sovereignty than is currently the case.

The ideological driver behind Brexit is a particular understanding of sovereignty, viewed in terms of ‘self-rule’ (implicitly or explicitly through Parliament). In the UK we are accustomed to thinking of sovereignty debates as relating to the EU or the ECHR. Were Brexit to go ahead, we may well end up replacing one of these concerns (the EU) with another, the WTO.

In the case of Brexit, until a new deal with the EU were negotiated, UK access to the single market would depend on membership of the WTO (though there is uncertainty on the detail) as both the EU and the UK are members in their own right.

What then does the WTO offer? At its heart, the WTO seeks to encourage non-discriminatory trade amongst its 162 members by regulating a panoply of potentially trade-restrictive practices. While these obligations are less onerous than those under EU law, it is important not to underestimate their effect. The WTO has found against support for the development of new large civil aircraft, ruled against measures seeking to protect sea turtles and restrictions on hormone-treated beef and genetically-modified organisms. Even a cursory glance at the history of WTO disputes demonstrates its wide reach. Indeed, the government’s proposed new sugar tax raises questions of WTO law as it may indirectly advantage domestic producers of sugary products.

If the UK were to conclude a new trade deal with the EU, or replace those the EU has already concluded across the globe (and to which the UK would no longer have access), WTO law also has a say. The sorts of trade deals that might be concluded must comply with WTO law, requiring liberalisation of ‘substantially all the trade’ between the participants (ie not only in those areas of interest to the UK). If the UK is to negotiate new agreements (and as quickly and widely as has been suggested) the concessions given would have to be considerable to make them appealing to trade partners as well as to ensure compliance with WTO law.

The scope of WTO law may be wide but its intrusion into the UK legal system is certainly less than that of EU law. Unlike EU law, WTO law is not automatically incorporated into UK law, does not grant individuals rights, and does not ‘trump’ UK law. This has its advantages: Parliament’s sovereign will cannot be overridden by the decision of a ‘foreign’ court or legislature. Should Parliament choose to, the UK could face down a decision of the WTO (as was suggested during the prisoner voting fiasco vis-à-vis the ECHR).

If we set aside the desirability of the UK being seen to violate international law, there is a more practical challenge. Where a member is found to have violated WTO rules, if they do not comply, they can be targeted with trade sanctions. These customarily take the form of increased tariffs which can have a serious impact on local businesses and industry exporting to that market.

There are instances where WTO members have taken exactly the decision mooted here – yet large WTO members like the EU can weather sanctions from, say, the United States exactly because the impact of the sanctions can be buffered by virtue of their size. The question we have to ask is – would the UK be in a position to tolerate sanctions from our much larger trading partners, such as the EU, China, or the United States? Within the EU we can take the hit, outside of it, the cost-benefit analysis may swing the other way.

It is telling that a parallel of our own EU sovereignty debate is commonplace in the United States. Each time the United States loses a case or does not offer protection to domestic industry, the WTO is identified as the source of this erosion of sovereignty. Even now, it is a hot topic in the current US elections. Nor are sovereignty debates limited to the WTO; NAFTA, the future EU-US Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, and the larger Trans Pacific Partnership, all spark similar concerns. Note that such agreements are comparable to the type of trade deal we would expect the UK to conclude with the EU.

Trade agreements necessarily imply a restriction on the regulatory autonomy of the State. States agree to limit their freedom to act so as to benefit from the advantages that non-discriminatory trade gives. The EU implies a great imposition on the regulatory freedom of the UK, yet it is within a framework that permits the amplification of UK interests globally. All trade agreements, whether bilateral, regional, or multilateral will entail a ‘loss of sovereignty’ in crude terms, though extremely few permit unified representation on the global stage or engagement with the rule-making. Taking into account the WTO framework which is ultimately the bedrock of world trade relations, and the implication it has for both sanctions and the possibility of concluding new trade deals, we might seriously question whether the ability to project our influence globally is not preferable to the sort of sovereignty enjoyed by pariah States that are incapable of engaging meaningfully in global affairs.

Featured image: Houses of Parliament by Petr Kratochvil. CCO 1.0 Universal via Public Domain Pictures.

The post Brexit and the World Trade Organization appeared first on OUPblog.

May 1, 2016

The Dismal Debate: would a “Brexit” mean more power for the UK?

“Money, money money. Must be funny. In a rich man’s world.” As an academic I’m highly unlikely to ever have either “money, money, money” or live in a “rich man’s world.” But as a long-time student of politics I’ve been struck by how the debate in the UK about the forthcoming referendum on membership of the European Union has been framed around just two issues – money and power. The political calculation being peddled in the UK is therefore embarrassingly simple: leaving the EU would mean that the UK had more money and more power.

This really has been a dismal debate. Those in favour of “Brexit” or “Bremain” have both engaged in an almost hysterical game of chasing shadows and creating phantoms. Shadows in the sense of making largely spurious claims about the impact of leaving the EU (i.e. “It would be very very bad!” or “It would be very very good”) when the truth of the matter is that no one really knows what would happen if the UK left the Union. Predictions must try to grapple with so many variables and uncertainties that the only way anyone would ever really know what would happen would be by the UK actually leaving. And yet part of this rather childish playground-like debate has been an automatic default to simplistic zero-sum games that are of little value in the real world. Would the UK really save any money if it stopped paying in to the EU budget? Well at a simplistic level it would but at a more sophisticated level it may not because the UK would then no longer receive funding back from the EU or have a seat at the table in major decisions concerning large infrastructure projects.

Would the UK really have more power, and the EU therefore “less” power, if the UK walked away? There seems to be no understanding of either positive-sum conceptions of power (i.e. by pooling some powers with other actors we overall actually gain more power and influence in some policy areas than we could ever have on our own) or the real world of global governance or international affairs. Does the UK really think that a small island just nine hundred miles long off the coast of continental Europe really still remains a global heavyweight with the capacity to “go it alone?” The seas of contemporary international politics rage like a storm: there is great value in setting sail in flotillas rather than in single small boats, and far better to have safe and secure anchorage points in the middle of a tornado. (And recent years have sent us political and economic storms, tornadoes and hurricanes that really should make the UK think twice.)

In this context, President Obama’s recent intervention was a beautiful mixture of charm laced with menace. The UK, was for him, taking a huge step into the unknown and caution was being urged. But Obama’s intervention also raised two issues that have simply not received the attention they deserve, issues that could transform a dismal debate into something quite different. The first is a shift away from a simplistic focus on power and money and back to a more basic focus on war and terror. To make such a point is not to engage in ‘the politics of fearmongering’ that is ripe in the UK at the moment but to make the simple point that the EU was from its very inception framed around the need to ensure peace through collective efforts. From the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951 the underpinning ideal of the EU knew the value of international co-operation and not just its price. In terms of fostering peace and co-operation across an ever-larger union of countries the EU can only be seen as a success.

This leads me to the second (‘Obama-esque’) issue: national confidence. I can’t help wondering if what is actually driving the Brexit campaign in the UK is a lack of confidence and national belief. This might seem odd in light of the desire to ‘go-it-alone’ but there is a lot of huff and puff behind the UK’s constant position as an “awkward partner” within the EU. The missing component – the political ‘X-Factor’ – of the current debate about the UK and the EU is not about leaving but about recommitting to the ideals and vision of the EU in a different but positive way. This is not the same as adopting a federal vision or embracing ‘ever closure union’ but it is about adopting a more positive ‘Yes We Can!’ attitude to re-shaping the EU with the UK at its core and not dragging its feet like a recalcitrant teenager on its periphery. Now wouldn’t that make for a more refreshing debate?

Image credit: London Eye Nightscape by Aero Pixels, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The Dismal Debate: would a “Brexit” mean more power for the UK? appeared first on OUPblog.

Book of the century: “The Subjection of Women”

In a dynamic demonstration of the motivating power of the written word, a ladies’ literary discussion group read The Subjection of Women in 1883. As soon as they had closed the book, they set up the Finnish Women’s Association to campaign for women in public life. It is not coincidental that in 1906 Finland became the first European country where women had the vote.

J.S.Mill’s book is, with Marx’s Capital, one of the two most important political books written in Britain in the nineteenth century. In it Mill argues ‘The legal subordination of one sex to another is wrong in itself and one of the chief hindrances to human improvement.’

Mill had believed in gender equality, he said, ‘from the very earliest period’ and revealed his commitment at the age of 18 in 1824 in his first published article in the Westminster Gazette.

In adult life Mill’s ideas were developed with Harriet Taylor, who became his wife. He said ‘all that is most striking and profound’ in The Subjection of Women was contributed by Harriet. Opinion is still divided on how much each contributed, but it is undoubted that his relationship with her was, as he said, ‘the honour and chief blessing of my existence’ and her early death from tuberculosis in 1858 was a blow from which he never recovered. ‘The spring of my life is broken,’ he said.

He published The Subjection of Women in 1869. No one could make definitive statements about the nature of men and women, he said, because equality had not yet been tried: ‘I deny that any one knows or can know, the nature of the two sexes, as long as they have only been seen in their present relation to one another. Until conditions of equality exist, no one can possibly assess the natural differences between women and men, distorted as they have been. What is natural to the two sexes can only be found out by allowing both to develop and use their faculties freely.’

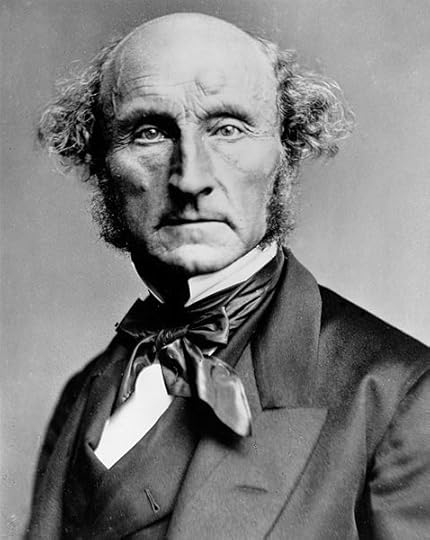

Image credit: John Stuart Mill 1870 by London Stereoscopic Company. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: John Stuart Mill 1870 by London Stereoscopic Company. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.In subsequent decades the book was widely translated and distributed. New Zealand legislators repeatedly referred to his ideas as they edged their country to becoming the first in the world to enfranchise women in 1893. Mill was sometimes said to have been responsible for the enfranchisement of women in New Zealand and Australia, but that was an exaggeration. Local factors and local campaigns were the most important causes, but their arguments needed the intellectual underpinning that Mill gave.

Norwegian journalist Ella Anker said women came together at that time to discuss this book, ‘how they cried over it, and dreamt over it, as if a new age was dawning.’ The Danish Women’s Association was similarly influenced by the book which was translated by the leading radical Georg Brandes. The most prominent Dutch feminist Aletta Jacobs became committed to women’s suffrage as a child when her father, who was in the habit of reading aloud to the family, read them a Dutch translation of The Subjection of Women.

The galvanising effect of the book had its limitations, however. The founder of the women’s movement in Italy, Anna Maria Mozzoni, translated it into Italian, but she was to grow old and die with no suggestion of votes for women in her country which came late to women’s enfranchisement, in 1945.

Marx famously said philosophers had previously sought to interpret the world where the point was to change it. Mill certainly felt that having political ideas was insufficient, and he worked to promote the feminist cause by standing for parliament.

Mill stood successfully for election in the Westminster constituency in 1865. He was able to move an amendment to Disraeli’s Electoral Reform Bill in 1867 to enfranchise women. Though the amendment was lost, more than a third of those voting gave support, which qualifies the assumption that the House of Commons, was as a body, opposed to votes for women and had to be brought round.

Among other arguments from human rights principles, Mill disparaged those who argued that votes for women would make a revolutionary change. He said, ‘The majority of the women of any class are not likely to differ in political opinion from the majority of the men of the same class.’ In other words, expanding the franchise to women was not going to change the balance of power, as women were not likely to vote on gender grounds, but according to their class or party loyalty. This prescient observation was overlooked by campaigners for the next fifty years who argued (as did their opponents) that the enfranchisement of women would bring about major political changes.

This made it more difficult for conservative societies to grant women the vote until experience showed that Mill was correct: it was only right and just that women should have the vote; and it was also a request that should easily be granted as it would make no difference to the political system.

Featured image credit: Voters outside a polling place, Brisbane, Queensland, 1907 by The Queenslander. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Book of the century: “The Subjection of Women” appeared first on OUPblog.

Mourning, memory, and performance

There is a wonderful Christopher Rush novel, Will (2007), in which Shakespeare says that what he does best is death: “I do deaths you see. And I can do the deaths of children. Their lips were four red roses on a stalk… – that sort of thing.” From the death of young Rutland in 2 Henry VI to the unexpected death of Mamillius in The Winter’s Tale, Shakespeare’s plays are full of loss.

If Shakespeare was interested in death, he was also interested in its corollaries for the survivors: grief and mourning. These are topics which belong to the area of study we now know as History of the Emotions. Critics trace a shift in attitudes to death about 1600. The shift was from consolation (there was no need to grieve because the dead were now in a better place) to condolence (from the Latin verb con-dolere: to sorrow with someone). If you sorrow with someone you acknowledge that they have reasons for sorrow. This shift in both attitude and terminology is very marked in Elizabethan poetry — G. W. Pigman pinpoints the shift quite precisely, to about 1600. That shift doesn’t map on to drama as easily as it does to poetry but it can’t be a coincidence that Hamlet was written in 1600-01 and is very preoccupied with how one grieves.

Part of the preoccupation is because of Hamlet’s preoccupation with acting and with sincerity. How does one perform sincerity? Isn’t that a contradiction in terms? In As You Like It, written just before Hamlet, one character says “the truest poetry is the most feigning.” Artifice/craftsmanship in poetry — like performance in grief — can actually be not insincere but an expression of sincerity.

It is the performative, of course, which Hamlet initially mistrusts: inky cloaks, sighs, tears, “dejected… visage, / Together with all Formes, Moods, shewes of Griefe … These … are actions that a man might play” (1.2.81–84). Hamlet draws a distinction here between the outward trappings of grief as displayed by the court – sighs, tears — and his own interior suffering.

‘Ophelia’ by Alexandre Cabanel. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

‘Ophelia’ by Alexandre Cabanel. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The relations among memory of loss, grief, and theatrical simulation reappear in the scene with the players in 2.2 where a narrative of loss (the fall of Troy) is performed. Hamlet asks the Player for “a passionate speech” and specifies “Aeneas Tale to Dido, and thereabout of it especially, where he speaks of Priams slaughter.” Far from appearing insincere, the Player’s performance is emotionally moving for both the actor and spectator. The actor’s performance is no different from the mourner’s performance–the tears, distraction, and broken voice of the mourner and the player are described identically by Hamlet in 1.2 and 2.2. What Hamlet distrusts in court behaviour, he admires in the theatre. When in Act 5 Yorick’s skull prompts the prince to dispense prosaic memento mori wisdom, Hamlet’s grief, although calmer, is not less sincere. It is just less performative.

The Reformation swept away many of the performative aspects of mourning which had characterized Catholic ritual. The rituals of mourning which should surround death and comfort the living are consistently maimed in Hamlet. The mourning period for Hamlet Sr is terminated incongruously by Gertrude’s remarriage; Polonius has an “obscure buriall; / No Trophee, Sword, nor Hatchment o’re his bones, / No noble rite, nor formall ostentation”; Ophelia is denied full Christian burial. Hamlet, Ophelia, and Laertes wander through the play suffering a grief that is denied the mediated outlet of full mourning. The prince’s infamous middle-acts stasis does not constitute delay so much as a comment on the unavailability of official forms of mourning, an unavailability reinforced by the cold indifference of the elegiac world of pastoral: the royal orchard harbours a serpent and hosts a murder; Denmark is an “unweeded garden”; Ophelia drowns amidst flowers and weeds; and all that “country” can provide in this play is the material for crude sexual innuendo. For Hamlet and Laertes, revenge takes the place of mourning; for Ophelia, madness. Revenge and madness can both be performed when mourning cannot.

If mourning is maimed, so is its associated entity, theatre. The Mousetrap is as truncated as the play’s funeral rites. Drama, like grief, requires performance: an interrupted play is as emotionally destabilizing as an incomplete mourning. The theatrical nature of the vocabulary in 5.2, as Hamlet and Horatio gaze at the court “Mutes or audience to this act,” leads to instructions for staging Hamlet’s funeral: “let this same be presently perform’d /…Lest more mischance / On plots and errors happen. … Beare Hamlet like a Soldier to the Stage” (my emphasis). The first complete performance in the play is about to take place; mourning and theatre finally coalesce.

The post Mourning, memory, and performance appeared first on OUPblog.

What is really behind Descartes’ famous doubt?

Introductory university courses in philosophy often cover Rene Descartes (1596-1650). Descartes’ enduring popularity stems in part from his openness about the reality of disagreement and his struggles to resolve it. “Philosophy,” he once wrote, “has been pursued for many centuries by the best minds, and yet everything in it is still disputed and hence doubtful” (Discourse on Method). Young people often encounter serious intellectual diversity and disagreement for the first time on their college campuses, so they easily relate to Descartes’ struggles.

In his master work Meditations on First Philosophy, Descartes focuses not on disagreements between people, but on the ways in which he disagrees with himself. Descartes is capable to taking up more than one perspective on things, and these perspectives seem to conflict. When he thinks about something that he “clearly and distinctly” perceives — such as “2+3=5” or “I must exist since I am thinking” — he can’t imagine how such a thing could be false. But when he views himself from a theological perspective and thinks about the power of God, he can imagine how these things could be false: God could build him to feel utterly convinced by false claims.

In his Third Mediation, Descartes tries to overcome this clash of perspectives, and the self-doubt it provokes, by proving that God cannot be a deceiver. But this introduces a new clash between theology and experience: a good God would not cause him to make mistakes, and yet he knows for certain that he has often gone wrong. In the Fourth Meditation, Descartes resolves this conflict by appealing to free will. God has given him perfect cognitive equipment. If he uses it correctly, he won’t go wrong. But how he uses it is up him, and he often uses it incorrectly. Instead of waiting for clear and distinct evidence to come in, he goes ahead and believes things that are uncertain. No wonder he is often wrong.

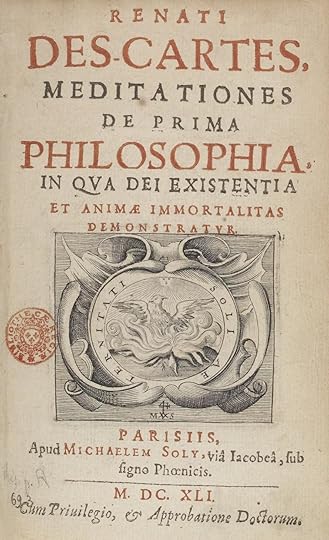

Meditationes de prima philosophia, 1641. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Meditationes de prima philosophia, 1641. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.This solution raises lots of questions. Can we really decide whether to believe something? And what does Descartes mean by “free will”? This last question is especially pressing, because Descartes says some very puzzling, seemingly contradictory things about freedom. He says that believing freely means having “two-way” ability: we can go ahead and believe, or we can wait for more evidence to come in. But he also says that when we perceive something clearly and distinctly, we can’t help but believe it — and nevertheless believe it freely!

It might seem that Descartes has a self-contradictory notion of freedom. But he really doesn’t. Descartes is working with a perfectly plausible notion of freedom. He thinks that freedom is the ability to do the right thing. When he perceives the truth of a claim with utmost clarity, he must believe it, and that is the right thing for him to do. But when a claim is sort of obscure, when there is evidence both for and against it, Descartes can either believe it, or not. The right thing is to wait for more evidence, and since he can do it, he is free. But he often is impatient and does the wrong thing.

The real trouble for Descartes’ escape from self-doubt is not his notion of freedom, but his belief in divine providence. Descartes thinks that every choice we make fulfills a divine plan established from before creation. Things must go according to God’s plan. Therefore, it seems that when we make wrong choices, we weren’t really able to do the right thing after all, and so aren’t free (as Descartes defines freedom). Descartes “solution” to this problem is an appeal to mystery: somehow, God can leave our bad free choices undetermined, even though it is certain that we will make them. In effect, Descartes tells us that we simply have to live with a clash between theology and experience: when we think of God, we realize God must be in control of everything, but when we think of ourselves, we know that we are often free. Somehow, both claims must be true despite the clash.

Insofar as Descartes’ philosophical project is an attempt to overcome self-doubt, it does not seem successful. His original reason for self-doubt was a clash between theology and experience. It is hard to see why, if this clash gave him good reason to doubt himself, the clash between providence and freedom would not do so as well. In the end, he seems to disagree with himself about the ultimate lessons to learn from disagreement!

Featured image credit: Portrait of Rene Descartes, by Frans Hals. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What is really behind Descartes’ famous doubt? appeared first on OUPblog.

April 30, 2016

How brothers became buddies and bros

The Oxford English Dictionary’s (OED) latest update includes more than 1,800 fully revised entries, including the entry for brother and many words relating to it. During the revision process, entries undergo new research, and evidence is analyzed to determine whether additional meanings and formations are needed. Sometimes, this process results in a much larger entry. Such is the case with the entries for buddy and bro, both of which ultimately trace their roots back to brother.

These two words were first covered in the 1972 Supplement of the OED with modest entries of just a single noun sense; in the revised entries bro has eight senses and one compound and buddy has five senses and five compounds. The length of the entries is vastly expanded: buddy is now more than eight times longer than it was in 1972, while bro is more than 14 times longer.

What happened to buddy and bro between 1972 and 2016? Some of the increased length merely reflects the increase in electronic resources and decrease in space constraints in the present-day OED, but it also reflects the increased prominence and diversifying use of the words since the mid-20th century. OED editors compiled and published additional draft material for both entries in the intervening decades, but it is now brought together in complete entries for the first time, enabling us to make apples-to-apples comparisons between these words and many others formed in a similar way.

When does a pronunciation become a new word?

The English lexicon expands in innumerable ways. For instance, new words can be borrowed from other languages (café), arise through imitation of a sound (like oink or boom), and be formed from existing English words by combining two words (cupcake), blending parts of two words together (as in brunch), adding prefixes or suffixes (nationalize or unfriend), or through various types of alteration (like the respelling of phat). One way in which existing words are altered is by spelling them to represent a particular pronunciation. This might be an exaggerated pronunciation (as in puh-leeze), or a regional or colloquial one (like pardner); when these become entrenched, they sometimes cease to be the equivalents of the words they derived from, and begin to take on new meanings.

The word brother has generated a whole passel of such derivations. The OED now records at least ten distinct words based wholly or in part on regional or colloquial pronunciations of brother: bra (often spelled brah in the United States), bredda, Brer, bro, bruh, bruv, bruvver, bud, buddy, and Buh. Although they share little in common besides their first letter, all of these spellings are in some way attempts to reflect the way brother was pronounced in a particular type of speech. (Bro and buddy have slightly more complex stories, in that the former was used as a straightforward graphical abbreviation before it came to represent a regional pronunciation, and the latter may be influenced by other dialect words and by the suffix -y.) These ten words all have a connection to brother but they have developed in different ways, not all of which overlap with the meanings of the word brother itself.

Semantic evolution

The chart below shows the main senses covered in the revised OED entries for the ten words derived at least partly from regional pronunciations of brother. These are the meanings that were most fully evidenced in the historical record for each word. Almost all of these meanings can be traced back to similar usages of brother, but buddy and bro—the two most commonly used words—have also developed unique meanings for which there is no equivalent in brother.

The earliest use of any of the words is the simple use of bro. as a graphic abbreviation of brother, meaning that it would have been pronounced as the full word. The revised entry finds evidence more than a century earlier than previously known, in the scholar Thomas Lupset’s A Treatise of Charitie, published posthumously in 1533. The abbreviation eventually came to be pronounced as it was spelled in the meaning ‘a male sibling’, for humorous effect, but that development seems to have happened separately from, and later than, the use of the word to represent a regional pronunciation.

The next usage to arise was as a means of addressing a man directly. This is the most common meaning, appearing in eight of the ten words, and appears first in buddy, as part of a depiction of ‘negro’ speech by the composer Charles Dibdin from 1788. Similar use of bredda, bra, and bud is attested in the 19th century, and of bro, bruvver, and bruv in the 20th. Below is a selection of characteristic examples:

Ah how you do buddy. (1788, Charles Dibdin, Musical Tour)

Bra, da whi side unoo da go? (1869, H.G. Murray, Tom Kittle’s Wake)

‘Marning sister’; ‘Marning bredder’. (1894, Daily Gleaner (Kingston, Jamaica))

‘Thanks, bro,’ the driver said. (1957, Herbert Simmons, Corner Boy)

‘Hey, bruh,’ I called. ‘You callin’ me?’ (1967, Piri Thomas, Down these Mean Streets)

Let me put you out of your misery, bruvva. (1988, Times)

I know it looks bad right now bruv, but you mustn’t give up. (1997, EastEnders)

Look brah, this game right here’s going to be your breakout game. (2014, Y. Post)

Another common strand of meaning, appearing in six of the entries, is use as a title preceding a man’s name (“Bro’ Bill”). This is associated especially with Caribbean and southern African-American use, and much of the evidence is preceding the names of animal characters from folklore: Brer Rabbit, Bro Fox, Bredda Toad, etc. Bra is first recorded in this way in Caribbean use, but since the mid-20th century it has been associated more often with South African English as a respectful title preceding a man’s first name; this usage seems to have emerged independently.

Interestingly, although “male sibling” is the most common and familiar use of brother in contemporary English, it doesn’t occur earliest or most often among these derivatives. However, it does turn up in a variety of different regional contexts, from Cockney bruvver to Jamaican bredda to American regional bud.

Forgive us all, ‘specially Helun, for bein’ so cross ter her little bruvver. (1867, Arthur’s Home Magazine)

‘My bud’s in the Marines on Guadal,’ a girl will say. (1945 in American Speech)

We know what our ‘Arold and ‘is bruvvers think of us. (1966, ‘Simon Harvester’, Treacherous Road)

Nowadays, you cyaan trust some buddy an sissy never mind them come-out pon one mumma-belly. (1992, Rooplall Monar, High House & Radio)

She was buried de next aftahnoon. By de next day, her breddah was also gone. (2006, Carolita Blythe, Cricket’s Serenade)

The root word brother has been used from its earliest days to indicate a notion of fellowship, and to apply to various non-blood relationships between men. Both of these strands of development carry over into some of our derivatives. For instance, brother’s use to indicate a fellow member of a particular group, (a comrade in arms, for example, or a fellow black person) is echoed by similar senses of bro, bredda, and bra, which are sometimes extended to a more generalized meaning akin to ‘guy’ or ‘dude’. Brother can also be used of a particularly close friend, a brother in all but blood (or more snappily, a brother from another mother, attested from 1989 in the entry added to the OED in this update). This meaning is echoed in half of our brother-derived words, but is associated particularly with buddy and, more recently, bro.

Buddies and bros

Buddy and bro are unquestionably the most well-established of these brother-derived words, and the 20th century saw both of them increase in frequency and develop new meanings.

A Navy buddy diver team checking their gauges together. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Kori L. Melvin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A Navy buddy diver team checking their gauges together. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Kori L. Melvin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.By the late 19th century, buddy had begun to acquire the special connotation which remains unique to it today—a person who is responsible for ensuring the safety or well-being of another, typically in a reciprocal pairing (as in buddy system). This grew out of a use of buddy to refer to either member of a pair of miners working in the same area of a mine. Another strand of meaning arose from this nuance during the AIDS crisis of the 1980s, referring to a person providing emotional support for a patient with AIDS, or (later) other incapacitating diseases.

Buddy’s usage began to rise precipitously between 1910 and 1920. As a term of address, it came to be associated particularly with American English, sometimes with sarcastic or aggressive overtones (“outta my way, buddy!”). Over the course of the 20thcentury, buddy also took on special uses related to different communication media. First, it was adopted in the language of Citizen’s Band radio (“10-4 good buddy!”). Later, it became conventional to refer to a film focusing on a close friendship (typically between men) as a buddy film or buddy comedy. And in the 1990s, when America Online (AOL) was on the cutting edge of computer communications, the term buddy list was introduced to refer to a display featuring a list of the user’s contacts in a messaging application.

Bro, on the other hand, did not see a significant increase in usage until the late 20thcentury. Buddy remains a much more common word in English, but corpus evidence suggests that bro is beginning to gain ground, probably due in part to its most recent meaning, defined in full in the newly revised OED entry as:

Orig. and chiefly US young man characterized as someone who addresses his friends and associates as ‘bro’; esp. one belonging to and socializing with a close-knit group of male peers, typically participating in activities perceived as male-oriented or unintellectual, and sometimes displaying boisterous or rowdy behaviour. Frequently somewhat depreciative.

As I’ve discussed in a previous post on the history of bro, this usage has become exceptionally productive in producing further new words by compounding (like bro hug (2001), first added to the OED in this update) and blending into so-called “portmanbros” (like bromance (2001), first added to the OED in 2013). In our present decade, each day seems to bring a new bro formation, from brogrammer to Bernie bro; many of these may never qualify for inclusion in the dictionary, but it seems likely that we will be tracking many more such words in the coming years.

Although ultimately derived from brother, bro and buddy have by now developed completely independent identities, effacing their original meaning. Their brethren, the other words discussed here, represent many different stages in the life cycle of words. Buh and Brer seem to be calcified in their folklore use, and are relatively rare, even moribund. In contrast, bra, bruv, and bruh are on the rise—they may go on to develop their own unique meanings, to be covered in future updates of the OED.

A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords Blog.

Featured Image: “best friends” by John D. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

The post How brothers became buddies and bros appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers