Oxford University Press's Blog, page 513

May 5, 2016

The hardest question for scientists

It shouldn’t be a question at all. But it often is. And how many scientists ask it? How many can answer with a clear conscience? Ideally, all.

The word conscience is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as: “Senses involving consciousness of morality or what is considered right.” The word conscience even has the word ‘science’ in it, from the word scīre meaning “to know”, or knowledge.

But this question of conscience goes beyond science.

There is one clear axis along which we are all asked to act in life – in favour of ‘self’ or ‘society’.

Do we always do what is best when it comes to deciding the balance?

In all pursuits there is an innate tension between the interests of self and society. This tension has existed as long as we’ve had human society of any complexity.

Do hunters share their catch with the rest of the tribe or eat it themselves? Do mothers feed themselves or their children first? Do officials take bribes that will put their kids through college or accept the risk of rejecting corruption, with all its dangers? Do scientists share their data with colleagues or hide it away so only they benefit from the value?

Science is one of the noblest of human activities and scientific activities undoubtedly have immense positive impacts on society – but can also be put to misuse in the wrong hands.

The beauty of science is that it is a knowledge beyond human invention. It is the pursuit of a higher reality, ‘truth’. Science is a process by which we gain human understanding of the physical laws that run the Universe. Science, is by definition objective, repeatable and self-correcting. Old ideas cave under the pressure of new evidence.

Yet, even science is not immune to breaches of conduct – because its practitioners aren’t.

The highest profile examples involve faked data and claims of ‘sell out scientists’ who are the shills of commercial ventures that harm society – for example, smoking.

Scientist and his microscope. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Scientist and his microscope. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.While such cases are hopefully the exceptions, underneath these headlines lie smaller self-serving actions – some of which would not be amiss on a soap opera.

Daily academic life is rife with examples of offences against the ‘higher purpose’ of science to accrue human knowledge without bias.

Obstacles can include the rejection of new evidence, battles of egos, silo-ing of data, or sitting too long on a theory that is patently wrong, just because it is yours, as in the epic battle for acceptance of the theory of continental drift and plate tectonics.

When C should best stand for collaboration, it often stands for competition. Antagonists have it in their powers to secretly squelch grants, subvert peer-review of paper and invite only insiders to conferences, all to stay ahead of the game. Or worse, commit the ultimate scientific sin of refusing to collaborate if it weakens one’s position or strengthens a colleague’s.

Given this, the hardest question every scientist has to ask is “Am I doing this for self or society?”

In an ideal situation both self and society wins. The individual gets proper credit, esteem and personal satisfaction for advancing human knowledge. Science is advanced without hindrance. That is a win-win and there is nothing wrong with rewarding self. When it doesn’t harm society, that is.

It has been suggested that scientists swear the equivalent of the Hippocratic Oath, or a “universal code of ethics for scientists”, just as doctors have for millennia and promise never to harm and only to act in favour of public good.

While few scientists in academia ever breach dangerous ethical boundaries, more might be vulnerable to institutionalized pressures to favour self in intensely competitive research environments.

Currently, features of academic life are stacked in ways that encourage scientists to put self first.

Showing ones worth often puts a scientist in direct conflict with duty to society. Scientists keep their jobs, and advance, based on esteem factors that are based on self-promotion. Key merit promotion factors include things like the number of papers you write, where they are published and whether you are the lead author. All promote the work of self. This is understandable but can put scientists, as people like everyone else, in conflicted roles.

Many scientists would love to change this landscape.

We should reward actions in science that help progress human knowledge and science – even over self.

To all scientists out there – how to do you answer the question?

To everyone – how do we best make an environment that fosters scientific activities that best benefit society?

Featured image credit: Bacteria, by geralt. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post The hardest question for scientists appeared first on OUPblog.

May 4, 2016

Not a dog’s chance, or one more impenetrable etymology

The word dog is the bête noire of English etymology. Without obvious cognates anywhere (the languages that have dog are said to have borrowed it from English), it had a shadowy life in Old English but managed to hound from its respectable position the ancient name of man’s best friend, the name it has retained in the rest of Germanic. Before formulating even a preliminary hypothesis of where dog came from, it will pay off to study the larger picture, that is, to inquire about some other known names for “dog” and also for various dog breeds.

A few such names are self-explanatory: for instance, spaniel and Bolognese (Spain, Bologna). Some easily give away their Romance roots: terrier is such (terra “earth”); others, like beagle and mastiff, are considerably less transparent. Poodle, from German, seems to designate a creature fond of splashing in puddles. Talbot apparently derives from the personal name Talbot: the figure of a greyhound was borne in the coat of arms of the Talbot family. Collie, we are told, is related to coal because the earliest breed was black. The words for “dog” and its breeds sometimes go back to epithets like “fierce,” “tame,” “swift,” “loud,” and even “musical” (the latter two describe the animal’s bark) or the predominant color (collie is not the only example). Hound may be akin to Latin canis “dog,” but the vowels match badly and final -d has never been explained. The origin of the Latin noun is also obscure despite numerous conjectures on its origin. The idea of the affinity between hound and the Gothic verb meaning “catch” (hinþan; þ = th) was given up long ago, even though this approach is rather attractive and originated with no less a figure than Jacob Grimm. Also, hunt is not a cognate.

The real bête noire of English etymology.

The real bête noire of English etymology.One more circumstance should be considered: the generic word for “dog” sometimes develops from the sense “female dog, bitch” or “whelp, cur.” To realize the odds facing the etymologist, we may follow the history of the noun tyke. Its source could have been Middle Low (= northern) German tike (disyllabic, of course; the same meaning) or Old Norse tík “vixen.” Although tyke usually means “dog” and especially “cur; mongrel” (let alone “child; toddler” and “an unpleasant, coarse man”—those are figurative senses), it occasionally denotes “horse” (so also in rather old texts) and “otter” (rarely). In my series on the fox (“Vulpes, vulpes”), I observed that the same word is often used for the fox and the wolf (compare Old Norse tík, above); the dog should be added to those two. But “otter” and especially “horse” look strange. Even if tike ~ tyke ever meant “cub” or “the young of any beast,” “whelp” and “colt” are hardly compatible.

In our search, we encounter many similar sounding words, with vowels and consonants alternating almost at random. Old High German zoha “bitch” (the modern form is Zohe), from toha, resembles Icelandic tóa “vixen.” Toha acquired the diminutive suffix and yielded Töle. Alongside Zohe ~ Töle, German dialects have tiffe, tifte, tēwe, tispe, tipse, ziwwe, zibbe, zeische, and tache or toche. Zibbe is especially instructive, for in different localities it designates “female hare” (the most common sense), “ewe,” “bitch,” and “female lamb.” Against this background, even the English trio tyke “dog—otter—horse” stops looking exotic. Our belief in the unity of the animal kingdom is further shattered when we remember that German tike resembles German Ziege “she-goat, nanny goat,” along with Zicke (the same meaning, and a few figurative senses) and Zicklein “kid,” the latter being a cognate of Old Engl. ticcen; Classical Greek (dialectal) ziga “goat” is a close neighbor.

Did Mary have a little tsibbe?

Did Mary have a little tsibbe?Several of the forms listed above (ziwwe, zibbe, tēwe, tiffe, tifte, and the like) are clearly phonetic variants of the same etymon, but zoha ~ toha ~ tóa cannot be reduced to it. Tiffe reminds us of Dutch teef “bitch,” while tipse resembles Norwegian dialectal tiksa “bitch; ewe.” Dictionaries state unanimously that all those words are of unknown origin. This verdict presupposes that there is a certain meaning behind tyke ~ tike, zoha, zibbe, and the rest, something like “black, swift, etc.” but we don’t know it. However, the variety of senses (“bitch,” “ewe,” “she-goat,” “horse,” “otter”) defies the efforts to find such a basic meaning. Even though among our animal names we find a Classical Greek word, it does not follow that we have to look for an impressive-looking Indo-European root. We seem to be dealing with some extremely vague general sense “young animal” or “female animal,” most probably domesticated. “Otter” looks like a late and aberrant extension of the primordial sense. At one time, tyke was derived from German Dachs “badger” or from Danish tyk “thick; heavy”; neither conjecture has any value. Equally unconvincing have been the attempts to find a Celtic etymon for tyke.

Jan de Vries (1890-1964), an active and successful etymologist, suggested that the words of the type discussed here go back to calls to animals; hence, according to him, the great variety in their phonetic shape. Unbeknownst to him, Hensleigh Wedgwood had a somewhat similar idea as early as 1856. Tyke, he wrote, was “originally a young dog, then an affectionate expansion for the animal independent of age.” He believed that the complex tik was more or less universal, and in support of his reconstruction cited the look-alikes from Icelandic and Saami; he did not know that the Saami word was a borrowing from Germanic. This line of thought is reasonable. The onomatopoeic factor must also have played a role in forming such words. No one would try to find a profound etymology for the sound-imitative bow–wow, arf–arf, or woof-woof. So why not have a noun like woofy or arfy “dog”? Don’t we have puss-puss and pussy? All this may (or may not) go a long way toward solving the origin of dog.

I have a personal stake in this hypothesis. Russian dogs go gav-gav (this is a loud bark) or tiaf-tiaf (a high-pitched impotent bark), and tiaf-tiaf is amazingly close to tiffe and teef, featured above. Also, in the version of the story of three little pigs I read when I was a child, the brothers’ names were Niff-Niff, Nuff-Nuff, and Naff-Naff. (Forget the Urban Dictionary, especially nifff.) In the later editions I have consulted the pigs were usually nameless, and my students have never heard about Niff-Niff, Nuff-Nuff, and Naff-Naff. Years later I discovered that Swedish pigs say nöff-nöff and began to wonder whether the famous English story has Scandinavian roots.

A lovable Yorkshire tyke.

A lovable Yorkshire tyke.It now remains for me to add a few lines about the nickname Yorkshire tyke. Those interested in the origin of the phrase should read a detailed article by J. Fairfax-Blakeborough on it in Notes and Queries, vol. 154, 1928: 439-40. A term of abuse, it has long since lost its offensive connotations. “None of the earlier dictionary makers connect the word [tyke] with Yorkshiremen, and, prior to about mid-eighteenth century, county and other literature has no reference to the word as meaning anything but a dog.” Tyke did have a few other meanings, but with regard to Yorkshire tyke, the author was right.

Image credits: (1) ‘Please play with me!’ by John Adams. CC BY-SA 2.0 via theadams Flickr. (2) Mary had a little lamb. Illustration by William Wallace Denslow (1902). Project Gutenberg EBook of Denslow’s Mother Goose. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Mural by the Savile Town Branch of the Calder and Hebble Navigation. Photo by Tim Green. CC BY 2.0 via atoach Flickr.

The post Not a dog’s chance, or one more impenetrable etymology appeared first on OUPblog.

War and Peace on screen

I’m 15 years old and I have just thrown up in the lavatory at the movie theater. Shaking too hard to reach the paper towels, I need to hide out there for the entire intermission of the third installment of Sergei Bondarchuk’s epic 1967 film adaptation of War and Peace. In its uncut version, the film is almost 9 hours long, requiring four separate screenings of almost 3 hours each, shown on two consecutive weekends of two nights each.

This is the first war film I have ever seen depicting in vivid colour and graphic close-ups, the chaos and brutality of the battlefield. I had grown up on Hollywood’s war with The Great Escape and Von Ryan’s Express. Despite the passage of almost 50 years, Bondarchuk’s “Battle of Borodino” episode still holds every record it broke in war film production. According to The Guinness Book of World Records, 12,000 men and 800 horses were used, the total cast of extras reaching 15,000. The aerial swooping cameras, swerving and dipping drone-like over interminable killing fields, were a cinematic innovation in 1968. The only thing comparable in my young viewing experience (and in the references of the film critics) was the camera pan over the Georgia-sun-baked and blood-soaked plaza, overlaid with miles of wounded begging for water and tugging at Scarlett O’Hara’s apron as she sought for the doctor to attend her cousin’s childbirth. But Gone with the Wind, in best Hollywood style, spared its pre-World War II audience: the camera panned backwards and away from the too painful vision of the wounded men as recognizable individuals, the bloody rags were minimally gory and moans were muted. Bondarchuk’s aerial investigation dove in for close-ups of every death and bloody encounter, forcing the audience to see each combat story in graphic detail, as Homer’s Iliad demands of its audience with every spear-thrust through the eye. We must recognize the destruction of a human being in every death, one after another through the chaos of hundreds and thousands killing and being killed, relentlessly, endlessly, ceaselessly. In the entire sequence, there is barely any dialogue. The Bondarchuk “Battle of Borodino” installment in its uncut version lasted 84 minutes, the equivalent of a feature length film.

In its spectacular display of the Red Army and the Red Cavalry, the episode was interpreted as one enormous cannon salvo fired at the height of the Cold War to vaunt the USSR’s military prowess. “It was a disgrace,” Bondarchuk complained, that “our national masterpiece” existed on film only in the Hollywood version by King Vidor. Highly acclaimed at the time, the 1956 American-Italian production was a valiant Cinema Luxe attempt, but necessarily did a hatchet job on the story lines to compress them into movie-house format. The low production values of the 1972 20-episode BBC adaptation, with a strangely Dostoevskian Anthony Hopkins as Pierre, lacked the budget for spectacular visuals.

Film still from Sergei Bondarchuk’s War and Peace, 1967.

Film still from Sergei Bondarchuk’s War and Peace, 1967.CGI and other technological breakthroughs have advanced possibilities for the small screen, facilitating some of the stunning effects of the current BBC production, but its cinematographers remain deeply indebted to the Bondarchuk version, from Prince Andrei’s whirling gnarled oak tree to the aerial camera work on the battlefields. In the 1960s, making great masterpieces “relevant” was the industry mandate; currently, making them accessible to contemporary audiences is the BBC gold standard. Andrew Davies, once described as the “serial sexer-up” of costume drama, is true to form here in taking screen time to render explicit what was only a brief rumour of incest, or going full frontal in an effort to shock and recruit his audience. So in terms of sex and death, this most recent adaptation delivers. But does it get Tolstoy right?

Bondarchuk demanded of his film collective that, “first and foremost, we must enter into Tolstoy’s world,” “we must become Tolstoy’s comrades.” At the same time, the demands of Soviet Realism meant that Bondarchuk had to make Prince Andrei “our contemporary”– the New Soviet Hero. Although the filmmaker had more freedom during the Thaw and under Brezhnev than he might have done five years before, he still necessarily suppressed most of Tolstoy’s philosophical reflections on war and peasant uprisings. As a result, his scenario skimmed over Nikolai Rostov’s rescue of the mourning Princess Maria from rebellious peasants — a risky narrative in a culture that preferred to celebrate Tolstoy as the father of the Revolution.

Nikolai Rostov as played by Jack Lowden in the BBC adaptation 2016.

Nikolai Rostov as played by Jack Lowden in the BBC adaptation 2016.The new BBC production arguably achieves something very strong by allowing Nikolai and Maria’s story to unfold completely. Usually submarined in film and television adaptations because his story “does not advance the action,” Nikolai Rostov has nonetheless been proposed by leading critics to be the real hero of War and Peace.

Readers of the work will appreciate what Davies has done to stage Tolstoy’s imagined version of his parents’ romance. These episodes have at last received a sustained cinematographic treatment in a beautifully filmed series of understated scenes played with simplicity and power. There is no one like Tolstoy for revealing the inner monologue of a man and a woman in a romantic encounter. The author tells us Nikolai and Maria are drawn to each other precisely because their every word and action instinctively displays restraint and sensitivity. Translating this kind of understatement to the screen is a challenge for the director and the players. And to Davies’ credit, Tolstoy’s theme of fate and individual freedom manifests here as well: never has Nikolai asserted his autonomy more forcefully than in resisting his mother’s pressure to marry an heiress, yet nowhere else in his narrative does apparently random chance effect such a momentous change in a character’s trajectory.

Davies has given us much to appreciate in his fidelity to Tolstoy’s portrayal of Nikolai Rostov, and the delicacy of his scenes with Princess Maria reminds us that, just as the visual spectacle of war could barely comprehend the meaning of each individual soldier’s death, so a dramatic scenario can only depict the surfaces of the characters’ inner world. Beyond the ballrooms and battlefield spectacles with their iconic scenes of Andrei’s ‘brave death’, it is the inner world of Nikolai Rostov that tells us most about the soldier’s experience of war. We must turn to Tolstoy’s writing for that. Fortunately, there should be plenty of time to read this great literary masterpiece through before the next adaptation makes it to the big screen.

Featured image: Still from Sergei Bondarchuk’s 1967 film of War and Peace.

The post War and Peace on screen appeared first on OUPblog.

The overwhelming case against Brexit

On 23 June, British voters will go to the polls to decide whether the UK should remain in the European Union (EU) or leave it in a maneuver the press has termed “Brexit.” As of late April, public opinion polls showed the “remain” and “exit” sides running neck–and–neck, with a large share of the electorate still undecided.

The economic arguments for remaining in the EU are overwhelming. The fact that the polls are so close suggests that a substantial portion of the British electorate is being guided not by economic arguments, but by blind commitment to ideology. In this, the British are not so different from the many Americans who support the economy-killing presidential campaigns of Donald Trump, Ted Cruz, and Bernie Sanders.

The main economic argument for remaining within the European Union is trade. The 28–member states of the EU constitute a single market, with free movement of goods, services, capital, and people. According to the UK government’s latest statistical release, nearly half of UK exports go to EU countries. Hence, a crucial question is what sort of relationship the UK would have with the EU if it decides to leave.

Supporters of Brexit argue that if Britain leaves the EU, it will be able to negotiate some sort of trade deal with its EU trading partners that would preserve the benefits of the single market. One option would be for Britain to negotiate entry into the European Economic Area (EEA), a group of non-EU European countries (e.g., Norway), which have negotiated access to the single market. Another option would be for Britain to negotiate a bilateral trade treaty with the European Union, much like Switzerland has done.

Concluding such an agreement is certainly possible, but it is unlikely that the EU would make a deal on terms that Britain would find as advantageous as full EU membership. After all, making it painless to leave the EU would encourage others to leave as well.

The UK Treasury released a report in mid-April analyzing the long-term consequences of leaving the EU, considering three alternative trading arrangements: (1) membership in EEA; (2) a negotiated bilateral trade arrangement; and (3) no particular agreement, but operating under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules which currently govern trade between countries that do not have a trade treaty. The Treasury’s analysis indicates that after 15 years, these three scenarios would leave the average British household worse off by an estimated annual £2600 (EEA scenario), £4300 (bilateral arrangement), or £6200 (WTO rules).

The trade-based argument in favor of remaining within the EU is powerful, and explains why it commands such widespread support among policy savvy individuals. The list of supporters for continued membership in the EU includes Prime Minister David Cameron, who was reelected last year with an increased majority (his Conservative Party, by contrast is split on the issue), the major opposition parties, including Labour, the Liberal Democrats, the Scottish Nationalists, and virtually all the minor opposition parties.

The Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, has said that the threat of the UK leaving the EU is the “biggest domestic risk to financial stability.” And a Financial Times poll of 100-plus economists found that more than three quarters thought that leaving would hurt the British economy; only 8% thought it would help.

If Brexiters succeed in pushing the UK out of the EU, they will have shut an important door to the rest of the world and endangered Britain’s economic future.

Support for remaining in the EU comes from outside the UK as well. The leaders of Germany, France, Ireland, and Spain, among others, have strongly backed Britain’s continued membership. US President Barack Obama similarly encouraged a vote in favor of the EU during a late April visit to the UK, arguing that a separate UK– US bilateral trade deal (favored by the Brexiters) would take at least 10 years to negotiate and implement, leaving the UK out of the current US-EU free trade negotiations. And eight former US Treasury secretaries—Republicans and Democrats alike—warned that leaving the EU would lead to a “smaller, slower-growing British economy for years to come.”

What ammunition do the Brexiters have?

Surprisingly little.

Brexiters complain about the burden of EU regulations. However, if the UK were to negotiate a Norway-style trade relationship with the EU, it would have to maintain many of the most costly regulations associated with EU membership. Brexiters also complain about the magnitude of Britain’s contribution to the EU budget. However, Britain’s net contribution of £6.5 billion is equivalent to less than 0.9% of the UK’s budget.

The most popular objection to continued EU membership is that Britain will be flooded by EU and non-EU immigrants, especially refugees. Here too, the economic argument is weak. Although Britain saw substantial net immigration last year, much of it from EU countries, the Conservative government has limited EU immigrants’ access to economic assistance, reducing any burden that they might place on British taxpayers. Further, foreign-born individuals in Britain are far more likely to have a college education than native born Brits, and so, in fact, are probably on average more productive than natives. As to concerns about non-EU immigrants, because the UK is not part of Europe’s passport-free Schengen area, Britain retains the right to stem any inflow of non-EU immigrants at its borders.

Brexiters’ objections to immigration sound very much like the scare-mongering over the arrival of foreign people that characterizes the Trump and Cruz campaigns, and the scare-mongering over the arrival of foreign goods by the anti-trade Sanders campaign.

The US and UK economies are more prosperous when they are open to the rest of the world. If Brexiters succeed in pushing the UK out of the EU, they will have shut an important door to the rest of the world and endangered Britain’s economic future.

Featured image credit: European Union Flags 2 by Thijs ter Haar. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The overwhelming case against Brexit appeared first on OUPblog.

Which planet are you? [quiz]

What is a planet? As defined by Oxford Dictionaries it is ‘a celestial body moving in an elliptical orbit round a star’. In our own Solar System, it was traditionally thought that there were nine such planets: Mercury (the closest to the Sun), Venus (the slowest rotating planet in our Solar System), Earth (our home), Mars (which is slightly pear-shaped), Jupiter (which has over 60 moons), Saturn (encircled by bright equatorial rings), Uranus (which has a peculiar magnetic field), Neptune (a gas giant), and Pluto.

(I was taught to remember the order of the planets from the Sun by using the phrase: Many Vile Earthlings Munch Jam Sandwiches Under Newspaper Piles.)

However, in August 2006, Pluto was declassified as a true planet and is now known as a ‘dwarf planet‘ (meaning that my ‘vile earthlings’ sit under just a single newspaper). Then, ten years later in January 2016 a new planet potentially entered the scene: Planet Nine. Currently only hypothetical, some scientists have outlined what they think this planet might be like, and where it came from.

Whilst learning about the planets in our Solar System, and then hearing all that has befallen them in the news over the past decade, have you ever wondered which one you might best get on with? Or which planet you would be?

We certainly have, which is why we’ve created the quiz below, to help you find out. You don’t need to worry, we haven’t left Pluto out of this one.

Featured image credit: ‘Size planets comparison’, by Lsmpascal. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Quiz background image credit: ‘Montagem Sistema Solar’, by NASA. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Quiz outcome image credits: ‘Mercury as Never Seen Before’ by NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons; Venus (Computer Simulated Global View of the Northern Hemisphere)’ by NASA/JPL. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons; Image credit: ‘The Earth seen from Apollo 17’ by NASA/Apollo 17 crew. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons; Image credit: ‘Mars Valles Marineris’ by NASA / USGS. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons; ‘Jupiter family’ by NASA/JPL. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons; ‘Color Enhanced Image of Saturn’ by NASA/JPL. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons; ‘Uranus vg2’ by NASA/JPL. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons; Neptune storms’ by NASA/Voyager 2 Team. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons; ‘PIA19857: Pluto in True Color’ by NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons; Globular cluster’ by skeeze. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Which planet are you? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

May 3, 2016

Unraveling how obesity fuels cancer

“We are getting more and more precise about the different risk factors for the various subtypes of cancer,” said Stephen Hursting, PhD, MPH, professor in the department of nutrition at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. One established factor is obesity, now well linked to at least ten cancers, including pancreatic, colorectal, endometrial, and hormone receptor–positive, postmenopausal breast cancer. “The connections between [cancer and obesity] seem to be getting stronger in part because the quality and quantity of data has increased, particularly data from large, prospective, epidemiological studies,” Hursting said.

Cancer Research UK and the UK Health Forum recently issued a report, Tipping the Scales: Why Preventing Obesity Makes Economic Sense, that estimates 72% of adults in the United Kingdom are predicted to be overweight or obese by 2035—including 45% of those in the lowest-income quintile projected to become obese. The uptick in obesity is predicted to increase the number of new cancer cases in the next 20 years by 670,000 along with an increase in other chronic diseases. According to Nicola Smith, a senior health information officer at Cancer Research UK, if these numbers are reduced by 1% every year from the predicted trend, about 64,200 cancer cases could be avoided over the next 20 years.

The body’s fat deposit memories

Avoiding substantial weight gain while maintaining physical fitness is a likely way to avoid metabolic imbalances such as insulin resistance and high circulating levels of hormones. Avoiding such imbalances, in turn, can decrease risk of type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and endometrial, postmenopausal breast and colon cancer according to observational studies. Yet, whether losing weight can decrease one’s risk of obesity-related cancers is trickier to study in part because monitoring such individuals takes a long time and because of potentially confounding factors that may distinguish those who remain overweight from those who can achieve and maintain weight loss.

As a window into understanding whether some obesity-associated markers remain even after weight loss and how this may affect cancer development, Hursting’s lab induced mammary tumors—a model of basal-like breast cancer—in mice that were obese, normal weight, and formerly obese. Despite a normalization in weight (a 10% reduction) and a normalization of insulin and leptin levels, both the formerly obese mice and the obese mice had similar tumor growth and similar circulating inflammatory markers in the mammary tissue. DNA methylation in the mammary tissue of both groups of mice was similar and higher than the normal-weight control animals, suggesting an epigenetic memory of the obese state in the mice that were obese but lost weight. The work implies that weight loss alone may not be enough to overcome some of the negative effects of obesity.

Two mice; the mouse on the left has more fat stores than the mouse on the right from Human Genome wall for SC99 on ornl.gov. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Two mice; the mouse on the left has more fat stores than the mouse on the right from Human Genome wall for SC99 on ornl.gov. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Hursting is analyzing samples from formerly obese women to see whether the observations in mice also hold true in people. “From the mouse study, we think there is an epigenetic reprogramming that occurs with chronic obesity,” Hursting said. “We are also testing if the amount of weight loss, and how the weight is lost, such as diet alone, diet plus exercise, or bariatric surgery, impacts cancer risk,” he added.

A few human studies show dramatic weight loss to be beneficial for reducing the risk of obesity-related cancers. Some patients who undergo bariatric surgery can decrease the risk of certain tumors including breast and endometrial. In a retrospective observation study, Susan C. Modesitt, MD, a gynecological oncologist and researcher at the University of Virginia Health System in Charlottesville, and colleagues found that of 1,482 women who had bariatric surgery, 3.6% developed cancer—mostly breast, cervical, and endometrial—compared with 5.8% of the 3,495 morbidly obese women who had not had bariatric surgery. In another retrospective cohort analysis, bariatric surgery reduced relative risk for developing uterine cancer by 71% and by 81% if the patient maintained a normal weight after the surgery.

Which metabolic factors?

“The next question is, what changes with bariatric surgery in these patients?” said Modesitt, who is focusing on the metabolic factors that can fluctuate with weight loss.

“We’ve seen a big jump in the number of endometrial cancers in the last 25 years partly because of obesity, and the assumption in the past has been that the main link was the conversion of extra androgens to estrogens in fat tissue by the aromatase enzyme.”

Yet hormones alone are not likely enough to explain the link. “There are so many intertwining pathways of growth factors, insulin, inflammation, and hormones that makes this really difficult to sort out the attributable risk to any single factor,” Modesitt said.

Recently, Modesitt and colleagues measured the metabolite changes of 68 women at high risk for obesity-related cancer who had bariatric surgery, reducing their weight by an average of 45kg (or 99 pounds; about 34.5% of their weight). After surgery, the women had improved glucose, insulin, and free fatty acid levels as well as decreased inflammation. “We found, perhaps not surprisingly, that once women lost weight, their insulin and glucose homeostasis improved. But whether improvements will make the difference for no cancer versus cancer for these women in the future, we don’t know yet.”

To better tease out the metabolic factors that may be causally related to cancer, larger studies are needed. “In my ideal world, I would do a study of 5,000 obese women, of whom 50% undergo bariatric surgery, and then look at the differences in cancer rates and potential obesity related carcinogenic factors between the two groups. But that study, spanning a decade or two, would be difficult to fund because of the high cost,” Modesitt said.

Where

Besides the amount of fat, researchers have recognized that visceral obesity—the fat around the midsection that surrounds organs, including the pancreas and liver—is a risk factor for heart disease, type II diabetes, and some types of cancer. Visceral fat appears to secrete more hormones and other molecules that affect glucose metabolism and tends to have higher levels of inflammation, according to Rachel A. Murphy, PhD, of the School of Population and Public Health at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

In a study under review, Murphy’s lab has dissected the pathways that link specific adipose depots and metabolic deregulation. Her team looked for metabolites in the blood in relation to subcutaneous, visceral fat and to overall body mass index to try to identify causal metabolic factors.

One fat depot that has been carefully dissected is the white adipose tissue of the breast. Andrew Dannenberg, MD, associate director of cancer prevention at the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, and colleagues found that inflamed white adipose tissue of the breast occurs in most obese women with breast cancer and is associated with increased levels of aromatase, the rate-limiting enzyme for estrogen biosynthesis. That local effect of inflammation and aromatase expression in fat tissue is thought to promote cancer progression in women with breast cancer and may be a marker of breast cancer risk. “Aromatase is as well-vetted a target in breast cancer as one can imagine. Large trials have shown women at high risk of breast cancer who take an aromatase inhibitor have as much as a 50% reduction in risk,” Dannenberg said.

Systemic metabolic syndrome also has been linked to increased breast cancer risk, but “exactly why is unclear,” Dannenberg said. Tying the initial demonstration of local breast tissue inflammation to systemic metabolic factors, Dannenberg’s lab showed that about half of the 100 women with early-stage breast cancer who have white adipose inflammation in the breast also had elevated insulin, glucose, triglycerides, and other markers of metabolic syndrome. In a second cohort of 127 women, inflammation was associated with a worse course of disease for women who go on to develop metastatic breast cancer. “This leads us to postulate that inflammation may be critical for understanding the established link between metabolic syndrome and breast cancer risk,” Dannenberg said. “However, if inflammation has multiple effects including contributing to insulin resistance, then anti-inflammatory strategies to reduce risk may be more effective than simply targeting insulin.”

Because the cause of breast cancer in normal-sized women is uncertain, Dannenberg is investigating both adipose inflammation and aromatase levels in metabolically obese but normal-sized women because he believes occult breast adipose inflammation may be a key driver of breast cancer risk in those normal-sized women. His lab also has begun an effort to develop metabolic markers that could reflect both inflammation and aromatase levels to noninvasively gauge breast cancer risk.

Many others are following suit to find both markers of risk and ways to reduce that risk. “I think we have well established the connection between obesity and cancer. We are now moving away from proving the connection to asking, ‘How do we disconnect the link?’” Hursting said.

A version of this article originally appeared in the Journal of the Nation Cancer Institute.

Featured image credit: On the left an abdominal CT of a normal weight person. On the right the abdominal CT of an obese person. Photo by James Heilman, MD. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Unraveling how obesity fuels cancer appeared first on OUPblog.

Jane Jacobs, even better at 100

The fourth of May marks the centenary of the birth of Jane Jacobs, patron saint of contemporary urbanism, at least for most urban planners, architects and local political officials in the US and for many of us who live in cities as well. Both by her writing and her activism, Jacobs promoted livable cities—walkable, enjoyable, sociable places where communities provide distinctive experiences and locals have a say in determining what goes on.

Jacobs’s primary text is The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which was published in 1961. But her life—for at that time, she was a feisty New Yorker—provides a complementary text about the virtues of fighting the machine. With fellow community activists in Greenwich Village, Jacobs successfully challenged plans of the city’s urban renewal bureaucracy that would tear neighborhoods apart by building highways and massive public housing projects. Her main opponent was Robert Moses, a public sector development czar whose control of federal government funds allowed him to reshape infrastructure, including parks, bridges, and tunnels, cultural complexes, and public housing, from the Great Depression until Jacobs’s book came out.

Jacobs’s ideas reflect the time in which she wrote, when government still seemed all powerful in cities yet was unable to counter the suburban flight of the middle class and the growth of an urban working class that was poorer, less educated and largely African American and Hispanic. However, Death and Life is not concerned with the economics of a declining tax base or racial ghettos. Instead, Jacobs confronted the existential crisis of older cities by focusing on their physical fabric and the ways it can encourage social interactions.

She praises cities for their dense, complex physical environment, built more or less to human scale. She expounds on the experience of both density and diversity in crowded streets, short blocks, and distinctive neighborhoods. She enumerates the shopkeepers who own small businesses on her street, who create a lively sense of public space and also watch out for public safety. Thinking of her female neighbors who carried out informal surveillance by watching passers-by through their windows, Jacobs coined the term “eyes on the street.”

“Jane Jacobs” by orionpozo. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

“Jane Jacobs” by orionpozo. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Jacobs rejected state-led urban renewal, personified by Robert Moses; postwar architectural modernism, embodied by faceless “towers in the park” designed by Le Corbusier; and market-led mass suburbanization, symbolized by middle-class rejection of the city’s diversity and squalor. Unforeseen by Jacobs in the 1960s, these points became the touchstones of gentrification.

It’s not hard to see how Jacobs’s appreciation of urban authenticity was shared by a small but growing number of highly educated men and women who also rejected the “great blight of dullness” that the postwar growth machine imposed on both cities and suburbs. Whether they nurtured an anti-modernist romanticism or a third-generation yen for ethnic roots, people wanted to live in “historic” neighborhoods and buy in “local” shops. These tastes were expanded by the counter-culture of the late 1960s and 1970s, and gradually found resonance with artists, writers, and college professors who talked and wrote about the virtues of social diversity, neighborhood scale and historic context, all features of full-blown gentrification by the 1980s.

The tragedy is that the capital investment that followed the first wave of gentrification refused to follow Jacobs’s rule that a community should manage its own “unslumming.” First, individual gentrifiers founded their own communities based on social homogeneity and shared aesthetic tastes. They developed polarized landscapes, gradually displacing longtime residents and stores. Then, seeing the appeal of these gentrified neighborhoods, larger real estate developers entered the fray. They built new housing at higher rents and turned rental apartments into condos. Unslumming requires capital that longtime neighbors often lack.

In our era of market-led development, it is crucial to celebrate Jacobs for speaking truth to power. But it is also crucial to devise a more effective politics of controlling capital investment and enabling communities to stay in place.

Featured image: “Love Graffiti in Gramercy Park” by Jeffrey Zeldman, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Jane Jacobs, even better at 100 appeared first on OUPblog.

The Friendly Viruses, and how they can help with the looming antimicrobial resistance crisis

In these days of Zika, Chikungunya, Dengue, and Ebola pandemics, and with the devastating smallpox, influenza, and polio epidemics of the 20th century still fresh in our collective memories, it seems counterintuitive to consider the possibility that viruses will ever be regarded other than with fear and loathing. However, if trials currently underway in Europe, Australia, and the US prove successful, then we may eventually reach a point where certain viruses are viewed with approval and even a degree of affection.

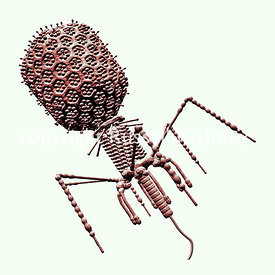

The viruses in question are bacteriophages (“phages”), a class of viruses that have evolved over three billion years as the natural predators of bacteria (hence the name phage = eat), operating as a kind of feedback system to control global bacterial numbers. We now know that phages are the most common biological entities on earth, outnumbering bacteria at least 10-100 fold, with an estimated total of 10 31 (think the number of stars in the sky!).

Phages were independently discovered by Frederick Twort (1915) and Felix d’Herelle (1917), but it was d’Herelle, a brilliant, self-taught French-Canadian who developed the field, naming the viruses, describing their life-cycle, and first applying them as powerful antibacterial agents in 1919, some 20 years before the discovery of the first antibiotics. All this without even seeing the individual bacteriophages, which were too small to be seen by the best light microscopes of the time.

They are split broadly into two types, lysogenic and lytic. Lytic phages are highly effective antibacterial agents that attach to and destroy their bacterial targets, and in the process replicate 50-200 times in roughly 15 minutes. In other words here we have a self-amplifying antibacterial which can increase its concentration (number) by a factor of two billion in just over two hours. Such agents should have huge potential in the post-antibiotic era. By selecting the right phages, those which are exclusively lytic, it is relatively straightforward to devise phage therapies that are very effective against pathogenic bacteria.

The fact is that we’re fast running out of antibiotics. It’s estimated that by 2050 antimicrobial resistance (AMR) will kill 10 million/year. Cancer kills 8 million/year. That’s right: this will be a bigger problem than cancer.

Two infective problems that are still with us, yet amenable to phage therapy, are typhoid fever and blood infection – bacteremia – with Staphylococcus aureus (SAB). Typhoid fever was much feared – it killed Abraham Lincoln’s son and Teddy Roosevelt’s mother- and it remains a scourge, with a global annual death toll of about 160,000. A highly effective phage therapy was developed by a group of doctors in Los Angeles in the 1940s. They intravenously (IV) infused phages against typhoid. Phages kill their target bacteria in a matter of minutes, and so too their patients often displayed what they described as a “truly startling bacteriologic and clinical recovery.” With just a little determination on the part of governments, this technology could readily be re-introduced.

The problem of SAB remains very serious, and is becoming more so with the immense ability of SAB to evade antibiotics. The 30-day death rate of SAB is around 20 -40%, yet there are many reports from the 1920s and 30s, from France and the US, of IV use of phages successfully treating SAB.

Image credit: Bacteriophage T4 Monochrome Shaded on White Sanguine by Russell Kightley, via Russell Kightley Premium Scientific Pictures. Used with permission.

Image credit: Bacteriophage T4 Monochrome Shaded on White Sanguine by Russell Kightley, via Russell Kightley Premium Scientific Pictures. Used with permission.In answer to the obvious question, phages are extremely safe. They only infect their target bacteria, so for example S. aureus phages only infect S. aureus. They are safer than antibiotics, which are now understood to cause collateral damage to our microbiomes. And our bodies are already awash with phages: the gut is full of them, and phages are the most common biological entities in our bodies. In contrast, some antibiotics, such as gentamycin, are highly toxic and demand extreme care in dosing. Clearly phage therapy needs to be revived on a large scale.

What can be done about the looming AMR threat? The first need is for serious money to be spent on the problem, and not just on phage therapy. There have been policy statements and hand-wringing from the highest levels, such as The White House and 10 Downing Street, but there’s precious little new money. New funds should be directed at research directly targeting the looming AMR threat.

Second, serious money should be earmarked for clinical trials. A critical bottleneck is in getting promising antimicrobial approaches – such as phages — into clinical trials. Big pharma doesn’t like taking risks, and these companies won’t invest in a new approach until it’s clinically proven to work. The high cost of clinical trials is often beyond the resources of start-ups.

Third, governments need to get serious about a whole range of other ways to better deal with the bad bugs. These could include strong support for antibiotic stewardship (using our current antibiotics more carefully, although this might only buy time), banning antibiotic use as growth promoters in agriculture, and better educating healthcare workers on hand-washing. Cancer is rightly attacked on many fronts. Governments and society spend large amounts on cancer research, and there are many charities aiming to help fund research into particular cancers, such as breast cancer, or cancers of children. We need to work just as hard if we are to stop antimicrobial resistance overtaking cancer as a global cause of death.

Featured image credit: Bacteriophage T4 Virus Group #2 by Russell Kightley, via Russell Kightley Premium Scientific Pictures. Used with permission.

The post The Friendly Viruses, and how they can help with the looming antimicrobial resistance crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

“Wood Street”: On the sound and Psalm 137 references of the Sacred Harp song

On every Saturday or Sunday of the year, if you know where to go, you will find people in the United States, Canada, even Europe singing from an oblong red-brown book called The Sacred Harp. Sometimes called shape note or fasola singing, Sacred Harp is a tradition of communal sacred singing that developed in New England after the American Revolution, migrated south and west, and was preserved for generations in Appalachia and the deep South, bringing communities together to sing four-part hymns and anthems. During a July heat wave I ventured to Kalamazoo, Michigan, where nearly two hundred singers have assembled for the annual Sacred Harp singing convention.

Mid-morning, a woman from Chicago named Judy Hauff walks into the steamy basement, running late. As serendipity would have it, the assembled singers are in the middle of singing one of Hauff’s own songs, “Granville.”

Judy Hauff is in unusual company in having three of her compositions in the latest edition of The Sacred Harp (1991), most of whose songs date back to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Even more unusual, she is the only one of the living composers whose songs have fully entered the mainstream of the canon. I’ve never been to a singing where at least one of them wasn’t called by a song leader. (Part of the Sacred Harp tradition is that everyone who attends the singing and wants to can choose and lead at least one song.) After the closing benediction, while the Kalamazoo people are moving chairs and packing up leftover food, we talk in a side room. I’m interested in a particular song of hers called “Wood Street,” which begins: “When we our wearied limbs to rest / Sat down by proud Euphrates’ stream,” one of many references to the famous Psalm 137 in the song.

The text is attributed to the Tate and Brady psalter of 1696, Hauff’s tune to 1986. The piece is memorable in several ways. It has a powerful rhythmic drive to it, a tangible groove, produced by the counterpoint of the voices in the chorus, with its repeated lines: And Zion was our mournful theme…. On willow trees that withered there. I mention this propulsive quality to her.

“Yes, I had heard that I could have put it in a duple time, but I thought no, I want that kind of relentless [Hauff makes rhythmic beating noises]. It just seemed to fit. It seemed to fit the words and the mood of—what do I want to say?—that their grief was unassuageable. It was something that they had to go through; they couldn’t go around it, they couldn’t skip it. They had to go through this step, this diaspora, this punishment for whatever reason it was. So there’s no stopping and breaking in the song, it just keeps going. I like that kind of inexorable feeling about it.”

“Photo of Original Sacred Harp” by Southflorida69. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

“Photo of Original Sacred Harp” by Southflorida69. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia CommonsThere’s also a strong modal sound to the song, I point out, something that sets it apart from most other songs in the collection.

“Oh yeah, I’m the big Dorian mode freak in The Sacred Harp; they’re like ‘Oh Judy, she’s gotta have the raised sixth.’ But I find that it makes a song so incredibly distinctive, it sounds like a different piece of music to me. Maybe not to other people—maybe they don’t even hear the difference—but I hear it strongly. It has a strong effect on me.

“And when I heard some of the older Southern singers doing it, naturally, they didn’t know they were doing it of course, but when I first went down in the mid-eighties and heard these older Southern people doing it I thought, Oh, my God. That book by George Pullen Jackson where he talks about it, and I thought, Really? And then I heard it first-hand, and I thought, Oh wow.

“Well, ‘Granville’ [another of her Sacred Harp songs] didn’t mean to have it, ‘Agatite’ does, and so does this. I just said, I’m gonna write it in. And I thought, if I don’t mark it all, the Yankees will flat it, and the Southerners will probably sing it correctly. But if I mark the accidental, I will force everybody north of the South to do it and I’ll just tell the Southerners not to pay any attention to the natural sign, just sing it. But I think everybody pretty much does it now with the raised sixth. I don’t know how to describe it, you know. I don’t know how it affects you, I just know how it affects me. It would sound terrible without it to me.”

I ask Hauff why she named the song “Wood Street.”

“All the tunes in the book are place names because the tunes are separate from the words in this literature. So, at the time I wrote this, there were like seven Sacred Harp singers in Chicago who lived on Wood Street. I myself live on Granville, and other friends of mine live on Agatite. So I thought, well, if you can name things ‘Wells,’ and ‘Abbeyville,’ and all these other place names, I’ll just, you know, I can’t name them ‘Chicago,’ but I can do different streets. So that was it. Ted Mercer [another venerable Chicago singer who also has a composition in The Sacred Harp] still lives on Wood Street.”

Why was she drawn to the text of Psalm 137?

“I was raised as a Roman Catholic so I really did not know a good history of the Jews. I just didn’t. I’m not a scholar at all! And being Roman Catholic I certainly never studied the Bible and learned verses, because they’re like, ‘We’ll teach you what that means!’ So I was comparatively ignorant next to all the other people that I’ve been singing with that grew up studying the Bible closely. So I was just borrowing from other tune books, you know, I’d just look through for texts that I liked. So sometime in my thirties or forties I just started in reading books about the history of the Jews, the Diaspora, and it just seemed a dreadful story, such a loss of glory, totally annihilated. So it struck me: the sense of loss they must have felt, certainly, expressed in these words.”

So was her interest in the psalm mainly historical, or was she interested how the psalm resonates with people today?

“Well, it was more historical. I thought, Gee, if I could go back in time and see what really happened…. I mean, obviously the Bible is tremendously slanted for sympathy to the Jewish people. It’s like: Oh, those Canaanites, they’re just a bunch of idol-worshippers, get ’em out of here, right? But the same thing is going on today: Oh, those Palestinians, get ’em out of here. It’s like they were depersonalized in the Bible, the Canaanites. They were nobody, they were nothing. They were not chosen people, certainly.

“And I wonder if it was kind of like it is today, where one group is trying to push the other out. In the old days, you know, We won. Our side won, the Jewish people won. Nowadays they are not having such luck, you know, they aren’t having the same kind of luck. So, I find those echoes very interesting: that really nothing’s been solved. Nothing’s been solved. The old enmities are there.”

I ask Hauff about how people have responded to “Wood Street.” She admits occasional misgivings over donating the song to The Sacred Harp rather than selling it to a publisher; she would have been receiving royalties from it for some twenty-five years.

“People love this song like I cannot tell you. I was stunned at the reaction to this song. I mean, I liked it, it satisfied me, but then, you know, there’s other things I have written that have satisfied me. But people came back to me—not the people in the South; they were not particularly interested in it, they could take it or leave it—but the people in the North, the new singers, the twenty-somethings, thirty-somethings, forty-somethings. People from Seattle to Maine to California and everybody in between just come swarming up to me: Sign my book. It’s my favorite song in the book. Favorite song in the book.

“I’m like, well, thanks—I’ve certainly hit a nerve with it. And I was very surprised and very pleased. I don’t exactly know what the nerve was, but it obviously.… That howling and misery, I think, reached people, and they thought: Yes, that’s the way it is. You know–something.”

This article is an adapted extract from Song of Exile: The Enduring Mystery of Psalm 137 by David W. Stowe.

Featured Image Credit: “Hymnal book” by jh146. CC0 via Pixabay

The post “Wood Street”: On the sound and Psalm 137 references of the Sacred Harp song appeared first on OUPblog.

Why whine about wining and dining?

Annual US expenditures on business entertainment likely exceed $40 billion. Such “wining and dining” is often viewed with suspicion, as a way for one entity to influence another’s decision makers improperly. Indeed, such concerns often lead governments and other organizations to limit what kinds of meals and other gifts employees can receive (consider, e.g., 5 Code of Federal Regulations Part 2635). Yet, at the same time many businesses encourage and permit their employees both to wine and dine and to be wined and dined. Why?

The rationale might, at first, seem obvious: firms expect to generate more business, better cooperation, or other profitable quid pro quo from those being wined and dined. But this begs two questions: first, why do firms let their own managers be the beneficiary of such largesse if its purpose is to induce their managers to pursue actions desired by other firms? And, second, if firms benefit from better cooperation and otherwise smoother business relations, why do they not directly provide their own managers with the necessary incentives to cooperate?

A rationalization for wining and dining can be offered in an environment in which there are (i) no tax advantages to the practice; (ii) firms, if they wished, could directly provide incentives to their managers that would induce the same level of inter-firm cooperation as wining and dining; and (iii) wining and dining may be subject to abuse (e.g., expense-account fraud). All that notwithstanding, wining and dining nevertheless proves a low-cost way for firms to provide incentives for inter-firm cooperation. Indeed, if there is no potential for abuse, firms can achieve a first-best outcome (i.e., maximum efficiency with the firms’ shareholders capturing all the benefits that come from doing so). Even when abuses can occur, firms still do better when they facilitate wining and dining than they would if they didn’t.

Why is this? The key insight is that although shareholders (the firms’ owners more generally) can provide direct incentives, those incentives are expensive because shareholders cannot directly observe whether their managers are behaving cooperatively. This asymmetry of information would permit managers to capture so-called information rents (remuneration strictly above that necessary to compensate them for the actions they take). In contrast, a manager directly observes whether her counter-party is being cooperative. Consequently, in the quid pro quo implicit contract between themselves, the managers can avoid paying information rents. In other words, the shareholders can take advantage of the managers’ ability to monitor each other to get around their inability to monitor the managers directly.

Does this mean we should never be concerned about wining and dining? Of course not

What about potential abuse? In the real world, there are at least two dangers: one, the firms’ managers could collude between themselves to wine and dine each other regardless of whether cooperation is immediately needed; two, managers could simply pocket funds allocated for wining and dining other firms’ managers (this is no ideal concern, 14.5% of embezzlement cases involve fraudulent expense reimbursement). If the first danger is present, but not the second, then shareholders remain better off permitting wining and dining if they value cross-firm cooperation highly enough (specifically, would wish to induce cooperation via direct incentives in the absence of wining and dining). Intuitively, even if the managers collude to wine and dine regardless of the need to facilitate cooperation at a given point in time, over time they will still find themselves needing to cooperate. The fact that there is wining and dining means the information rent attached to such cooperation is less than it would be absent wining and dining, which means the shareholders are better off.

Likewise if the second danger, possible embezzlement, is present, but not the first, then shareholders are also better off permitting wining and dining (despite the potential for embezzlement) if they value cross-firm cooperation highly enough. Basically, the shareholders of one firm can utilize the manager of the other to help them police against embezzlement: the other firm’s manager, because she would not be wined and dined when she should based on her cooperation, has an incentive effectively to blow the whistle on embezzlement by withholding future cooperation, to the detriment of the embezzling manager.

What if both dangers are present? That is, what if managers are freely able to collude and there is zero direct deterrence of embezzlement (firms can never catch embezzlers)? In that case, wining and dining ceases to be of benefit. Yet, it doesn’t cost firms either: in this scenario, funds for wining and dining effectively represent an increase in managers’ base salary, so firms can reduce the base salaries by that amount. In other words, wining and dining simply becomes an alternative form of compensation (moreover, if tax advantaged, it could be a cheaper form of compensation).

Does this mean we should never be concerned about wining and dining? Of course not, but what this article reveals is that suspicion need not be the only reaction nor that letting one’s employees be wined and dined is without benefit.

Additionally, just as ‘The Market for “Lemons”’ by George Akerlof isn’t simply about used cars, this analysis isn’t solely about wining and dining. Rather, it has a more general message about how principals (e.g., shareholders) induce their agents (e.g., managers) to cooperate when such cooperation is personally costly for agents to provide, but beneficial to the principals. The key insight is the principals can leverage the agents’ better ability to monitor each other to obtain outcomes that are more profitable to them.

Featured image credit: ‘Restaurant’, by Skitterphoto. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Why whine about wining and dining? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers