Oxford University Press's Blog, page 261

April 19, 2018

Rome: the Paradise, the grave, the city, the wilderness

The following is an abridged extract from The Rome We Have Lost by John Pemble and discusses how Rome, the eternal city, the centre of Europe and, in many ways, the world evolved into a city no longer central and unique, but marginal and very similar in its problems and its solutions to other modern cities with a heavy burden of “heritage.” These arguments illuminate the historical significance of Rome’s transformation and the crisis that Europe is now confronting as it struggles to re-invent without its ancestral centre—the city that had made Europe what it was, and defined what it meant to be European.

Rome has long featured in Western thinking as the threshold of a transfigured existence. Poets had been going there since 1341, when Petrarch travelled from Avignon to be immortalised by being crowned laureate on the Capitol, and an unending procession of painters, sculptors, architects, composers, philosophers, historians, antiquarians, connoisseurs, and sentimental tourists had followed, lured by the poetic promise of apotheosis. By the early seventeenth century, no education was deemed complete that had not encompassed Rome, the central shrine and academy of civilisation, and an assurance of rebirth both historical and metaphysical. In Rome, a mystic marriage of the sacred and the profane had made humanity divine, and the divine human.

In 1863 historians still spoke of two Romes. The English, Italian, and French adjectives ‘ancient’, ‘antica’, and ‘ancienne’ had been linked to the first of these Romes in the early sixteenth century. By then it had become necessary to distinguish between the Rome of the Caesars and the sumptuous Rome that the popes, by demolishing its buildings and recycling the marble, were creating in its place. This second city was referred to as ‘New Rome’ (Nova Urbs) in a descriptive guide of 1510, and the designation served until the end of the nineteenth century. By 1952 two had become three; Rome had been transformed to a degree unmatched by any other major city in that age of urban demolition and development. ‘New Rome’ was then transferred to the third city on the site: a modern megalopolis that lived for its own purposes, proclaimed its own values, and built its own monuments. The second city now became ‘Old Rome’. Each of these Romes was perceived very differently from the others, because each had its distinctive cultural signature and historical tempo.

The cultural signature of ancient Rome was epic. It was in poems of immense length, dramas with hugely magnified characters, films with casts of thousands, histories in multiple volumes. Its story moved slowly but inexorably through a millenarian chronology from heroic beginnings to a world-shaking end, from brick to marble and from marble to ruin: a saga of rise, decline, and fall that had for centuries served as an exemplar for all republics and a warning to all empires.

Old Rome was measured on a more human scale, in the poetry of Byron and Shelley, the novels of Germaine de Stael, Nathanial Hawthorne, and the portraits and landscapes that were brought back from the Grand Tour. Everything about Old Rome was old, and only its ruins were older than its ruling dynasty of sovereign pontiffs. To go to Old Rome was to be afflicted by the wreckage of empire and by grim intimations of mortality; yet at the same time it was to be consoled by sights, sounds, and silences that transcended the havoc of circumstance and time. Its existence was periodically threatened by momentous events – invasion, revolution, war; but then everything would again be much the same, and history would seem to have passed by and left Old Rome in its haunted interlude between the nevermore and the not yet.

New Rome’s cultural significance was in journalism, fashion, films, and football. Its pulse raced in stations, airports, and arterial roads. It lived by growing, and it grew almost to suffocate in its own excess.

New Rome’s cultural significance was in journalism, fashion, films, and football. Its pulse raced in stations, airports, and arterial roads. It lived by growing, and it grew almost to suffocate in its own excess. Rome fed its voracious appetite for land by devouring the rural Campagna, the classical landscape of Latium that had surrounded Old Rome with Arcadia and malaria. It was now girdled by a fifty-kilometre ring road intersected at thirty-three junctions by converging radial motorways. It was cleaned, paved, drained, tram lined, and tunnelled for a metro. It curbed the unruly Tiber with embankments and conduits, transformed its ragged shores into boulevards, and threw ten bridges across its yellow stream. It delivered drinking water to fifth-floor taps, and the blaze of its nocturnal illumination cast an artificial twilight on the clouds. But it was blighted by congestion, corruption, crime, and noise and its air was so polluted that it made historic stonework crumble and crack. New Rome made no trysts with foreign poets and sentimental travellers. Visitors to Old Rome had recalled the Colosseum as a moonlit ruin in solitude; visitors to New Rome recalled it, if they recalled it at all, as a floodlit monument on a traffic island. To those who remembered the starry darkness of Old Rome—but forgot its medieval smells and alleys ankle-deep in filth – New Rome was a vortex with emptiness at its heart.

Yet despite all this evidence of plurality and variation, the idea of immutability had always been inseparable from Rome. Proverbially, Rome was ‘eternal’ and ‘immortal’. These designations derived from its sacramental status in pagan and Christian culture, and from its will to survive by recycling the ruins of its own past. They denoted a mystic trinity: a city that was three cities in one. Each Rome, in each of its configurations – republican, imperial, medieval, Renaissance, Baroque, Fascist, post-war – had always subsumed what came before and prefigured what came after. A sensitive ear heard always in the music of Rome the same theme in different keys.

By 1952, Old Rome no longer existed and much of Europe was rubble and ashes. Modernity, endlessly and fretfully unstable, had cherished Old Rome in order to destroy it. But in the postmodern view Old Rome was not a victim, it was a culprit. It had been the centre of the modern world, and it had been modernity’s accomplice and example in its cosmic intellectual enterprise – an enterprise that postmoderns incriminated as the author of Europe’s catastrophe.

The Romano-centric world, with its mantras of reason, progress, and syntax, with its absolute values and its universal truths had, they argued, provided an endorsement for intolerance and a template for tyranny. Then, towards the end of the twentieth century, their verdict was in its turn being challenged, and a reversal of roles and reputations was bringing the story of Old Rome full circle. The accusers were now themselves accused – of deluding themselves that they had escaped from modernity, of falsifying history, of conducting an intolerant, totalitarian intellectual enterprise of their own. At the same time, the culprit was again becoming a victim. The Romano-centric world was being rediscovered as a benefactor of mankind, and Old Rome attained apotheosis as the Rome we have lost—a fleeting triumph over ruin and disorder.

Featured image credit: Panorama by sosinda. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post Rome: the Paradise, the grave, the city, the wilderness appeared first on OUPblog.

Learning about the First World War through German eyes

Thanks to the ongoing centenary commemorations, interest in the First World War has never been higher. Whether it be through visiting the poppies at the Tower, touring the battlefields of Belgium and France, tracking grandad’s war or digging in local archives to uncover community stories – unprecedented numbers of people have come face to face with their history in new and exciting ways. There are a few aspects missing from the commemorations held so far, however. For instance, there’s so much about the dead that we forget the sacrifices made by those soldiers who survived (nearly 90% of them) as well as by those who stayed at home. Equally, we tend to focus narrowly on the Western Front, when this was, after all, called a ‘world war’ for good reason. In this article, though, I want to concentrate on another aspect I think we have too often missed during the centenary. It would be easy, observing the commemorations of the past four years, to think that this was a British-only event. The fact that British soldiers fought alongside allies, most obviously the French, and against human enemies, most notably the Germans, is often skipped over, and we tend to look at the war from an exclusively British perspective. If, however, we see the war, not through that familiar lens, but through German eyes, we can learn a lot and challenge some hoary old myths. Here are five examples:

1) The German Army

Myth: The German army was a superb tactical instrument, a true meritocracy with a very flexible system of command which enabled fast responses and great flexibility. It learnt and adapted to the challenges of the new warfare with speed and skill, developing ‘stormtroop’ tactics in the attack, and elastic ‘defence in depth’ tactics when under threat, both of which underpin modern tactics even today.

Reality: The weaknesses within the German army contributed greatly to its defeat. The officer corps was riven with cliques and patronage. Senior commanders interfered all the time in the operations of their subordinates. It was overtaken in the race to innovate by the British and French, who created new ways of fighting by 1918 to which the Germans could find no answer.

2) Arrogance

Just like the British in Blair’s Wars, the German military’s confidence in its ability to solve problems outran its capability. If the German army hadn’t presented the Schlieffen Plan as a workable military solution to Germany’s political problems, the war might never have started. Once war broke out and the Schlieffen Plan had failed, the high command continued to believe that it could find tactical answers to the impossible strategic situation Germany had created for herself, and so refused to consider any kind of climb-down. The army’s failure to be honest with itself, or with its politicians, cost Germany dearly. Arrogance loses wars.

“The army’s failure to be honest with itself, or with its politicians, cost Germany dearly. Arrogance loses wars.”

3) The French…

…were seen as more of a threat by the Germans than the British. Not only did the French carry the main brunt of the fighting on the Western Front for at least the first two years of the war, but right to the end of the war the Germans saw them as more skilled fighters than the British. The troops of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) were seen as brave but clumsily handled in battle, poor at coordinating attacks and exploiting success. On the other hand, politically, London was seen as the centre of gravity of the Entente. In March 1918, the German army launched its final desperate attempt to win the war with an attack on the BEF: partly because it felt the British were a softer target, and partly because they felt that knocking the British out of the war could cause the French to fold.

4) Learning and adaptation

Myth: the war was a static, sterile stalemate where everyone just kept bashing away in the same unimaginative and futile manner.

Reality: it was a cockpit of furious innovation. Every time one side came up with some tactic or measure to give it an edge, the other raced to counter it. Brand new technologies such as the aeroplane and the tank were developed as weapons and built into radically different ways of fighting war which, by 1918, were almost unrecognisable to the soldiers of 1914. Learning and adaptation constituted another front in the war, one contested no less savagely than the physical fighting fronts.

5) Winners and losers

Myth: This was the war no one won. Little changed, and nothing was solved. Domestic social and political change remained glacial. In international relations, it took a second, even more terrible, war, to resolve the German question.

Reality: Domestically, it is true, not much changed in Britain. There were no homes for heroes, and certainly few jobs. Some women got the vote, but they would probably have got it anyway. Politics went on much as before. In much of Europe, however, everything changed. Revolutions brought down the empires of Russia, Austria-Hungary, the Ottomans, and of Germany herself. They swept away monarchies and ruling classes which had endured for centuries. The tragedy, for Germany and the world, was that the Weimar republic which took over from the Kaiser was too weak to withstand the ravages of the Great Depression and the demonic force represented by Hitler and the Nazis.

It’s not always easy to see wars from all sides. Language can be a barrier, records can take digging to find, and everything takes time and money. But now, a hundred years on from the horrors of the First World War, surely we can start to make the effort to do so.

Feature image credit: The Emperor presents the Iron Cross to the Heroes of Nowo-Georgiewsk. Paining by Ernst Zimmer, 1915/16. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Learning about the First World War through German eyes appeared first on OUPblog.

April 18, 2018

Next lane please: the etymology of “street”

As long as there were no towns, people did not need the word street. Yet in our oldest Germanic texts, streets are mentioned. It is no wonder that we are not sure what exactly was meant and where the relevant words came from. Quite obviously, if a word’s meaning is unknown, its derivation will also remain unknown. Paths existed, and so did roads. Surprisingly, the etymology of both words (path and road) is debatable. This holds even for road, which looks perfectly transparent (isn’t a road a place meant for riding? See the post for 20 August 2014). Path is even more obscure (see the post for 4 November 2015). As could be expected, there is no native Common Germanic word for “street.”

Today’s definition of street is less straightforward than one can expect (the pun, though unintentional, was too apt to sacrifice). I am quoting The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology: “… paved road, highway (surviving in names of ancient roads such as Watling Street); road in a town or village.” Engl. street, like its cognates in Dutch and German (straat, Straße), goes back to Latin strata, a feminine adjective, part of the phrase via strata “straight way.” Italian strada and Spanish estrada are derived from the same source.

Watling Street, famous, among other things, for a bloody battle. Image credit: A map of Watling Street overlaid on the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica map of Roman Britain by Llywelynll. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

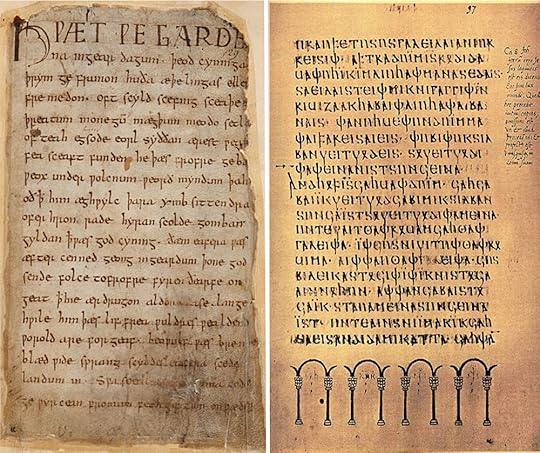

Watling Street, famous, among other things, for a bloody battle. Image credit: A map of Watling Street overlaid on the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica map of Roman Britain by Llywelynll. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.In English, the word is old and occurs, among others sources, in Beowulf. Even though the date of the poem is a matter of contention, there is, I think, enough reason to believe that the text was composed in the eighth century and reflects the realities of that time (the manuscript is two centuries later, and the action seems to be set in the early 700’s).The poet informs us that the “street” (strǣt) Beowulf and his companions rode to the king’s palace was stānfāh, that is, embellished with stones, most likely, paved. In any case, it was not lined with houses. In the same poem, the word strǣt occurs as the second element of two compound nouns designating “way across the sea.” It follows that the strǣt did not have to be “straight.”

From the fourth century CE we have part of the New Testament translated into Gothic, a Germanic language, now dead. In the extant part of the text, the translator (Bishop Wulfila) needed the word for “street” twice. Here are the relevant passages from the Authorized Version. Luke XIV: 21: “Get out quickly into streets and lanes of the city….”; and M VI: 5: “…for they love to pray standing in the synagogues and in the corners of the streets….” Wulfila used different words for “street,” though in the Greek text, the word was the same, namely plateîa, a feminine adjective, like Latin strata, with the noun following it (hodós) implied. In Classical Greek, hodós meant “way,” while “street” was only one of the word’s senses. Engl. hodology, if you are interested, means “study of pathways.” (For “lanes” older Biblical Greek has hrúmas, approximately, “narrow streets”; the Gothic gloss for it is staigos “paths.”)

These are pages from two great monuments: the Old English Beowulf and the Gothic Bible. Image credits: (Left) The first folio of the heroic epic poem Beowulf via the British Library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (Right) Polski: John 8 by unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

These are pages from two great monuments: the Old English Beowulf and the Gothic Bible. Image credits: (Left) The first folio of the heroic epic poem Beowulf via the British Library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (Right) Polski: John 8 by unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.In the first passage, Gothic has gatwo, and in the second, plapjo. Wulfila was a translator of great talent, and his choice of words was remarkable. Obviously, he did not equate “streets and lanes” with the “corners of the streets.” He seems to have needed a derogatory term for those corners, but no one knows anything about his plapjo. A place where people’s tongues went “plap-plap,” that is, where passers-by “blabbered”? A sound-symbolic or sound-imitative piece of Gothic slang? We will leave hypocrites to their own devices, let them pray at the crossroads, in the hedges, or wherever they wish, and turn to gatwo. Despite some phonetic difficulties, which I’ll pass by, gatwo is probably a cognate of (Old) Icelandic gata, known to many from Modern Swedish, Norwegian, and Danish gata ~ gate ~ gade.

This brings us to Engl. gate. There are two words, spelled and pronounced as gate. One means “street,” again surviving in place names. It also meant “journey” and “manner of going,” familiar to us from gait (which is another spelling of the same word; no connection with gaiters!). This gate appeared only in Middle English and is, almost certainly, a borrowing of Scandinavian gata. Even if we assume that gata and Gothic gatwo are related, we will still know next to nothing about their etymology. However, the Gothic word held enough appeal to its neighbors to be taken over into the Baltic languages. In Latvian, it exists almost in its primordial form (gatwa); the Lithuanian form is nearly the same.

Sometimes the impression is that with gata, gatwo, and the rest the situation is the same as with path. It is as though we are dealing with a migratory Eurasian word. First, there is another and much more familiar Engl. gate “a hinged barrier” (the family names Yeats and Yates go back to this word). Its cognates usually mean “gap, hole, opening; anus.” More important, in Sanskrit and Avesta, gātù– designated “way, path,” seemingly from “path across a swamp,” and in Slavic, gat’ and other forms like it mean “dam, dyke; rubble; brushwood, etc.” All of them refer not so much to impassable places as to the means of crossing them. Engl. gat1 and gat2 are believed to be unrelated.

Via strata. Sic transit…. Image credit: Casserole Breakfast Dinner Meal Dish Eating Fresh by nastogadka. CC0 via Pixabay.

Via strata. Sic transit…. Image credit: Casserole Breakfast Dinner Meal Dish Eating Fresh by nastogadka. CC0 via Pixabay.Numerous ingenious attempts have been made to explain the origin of gatwo. Perhaps ga– is a prefix (such a prefix existed; German ge– in genug and e- in its English congener enough are the relics of ga– ~ ge-). Or –two may have something to do with the numeral two (“a passage between two sides”?). Conversely, ga– may be a stub of the word for “go.” Those are the most attractive of the many hypotheses offered in the past. Modern dictionaries only say mournfully: “An obscure word” or “Origin unknown.”

In all probability, the Germanic word for “street” (gatwo and its look-alikes) referred to some passage. German has the expected word Straße “street” and Gasse, a cognate of Engl. gate “street,” and it means “a small street; lane.” But Wulfila used staigos for the “lanes” of the Authorized Version. If he were writing Modern German, he would probably have said: “Straßen und Gassen.” It would be good to get some help from the etymology of the word lane. This word is old and has cognates in Old Frisian, Dutch (both Middle and Modern), and Scandinavian. Characteristically, in Old Icelandic, it meant “barn; great heap; row of houses,” and “street.” Once again we have to conclude that “street” is not the word’s original meaning, but one wonders what “barn” and “heap” have to do with a row of houses. The Icelandic house was made up of several sections; one was meant for the sheep that warmed the place in winter by their breath. Hence “row of houses” and “heap”? In Old English, lane sounded as lane (two syllables!) and lanu, and this is all we know about it. The suggested etymologies are uninspiring, to say the least.

It must have been hard to be streetwise in the Germanic-speaking world two thousand years ago and some time later. One is left with the conclusion that, except for street, which is a borrowing, we have no clue to the words so important for the history of medieval material culture.

Featured Image Credit: This is an Icelandic house. Is the way from it to our street straight? Image credit: Turf roof of Glaumbaer, Iceland by TommyBee. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Next lane please: the etymology of “street” appeared first on OUPblog.

Paris in Translation: Eugène Briffault’s Paris à Table [excerpt]

“When Paris sits down at the table, the entire world stirs….” Eugène Briffault’s Paris à Table captures the manners and customs of Parisian dining in 1845. He gives a panoramic view of the conception of a dish (as detailed as the amount of coal used in stoves) to gastronomy throughout the city—leaving no bread roll unturned as he investigates how Paris eats.

The below excerpt from Paris à Table (translated into English by J. Weintraub) provides statistics to capture the magnitude of the Parisian way of life.

What a people eats, then, is known; but nothing is known of those private customs and manners that show their true character under a picturesque and lively appearance, constantly in motion. That is what we are trying to do for Paris.

Homer’s heroes and the children of Master François’ imagination are dwarfs whose pygmy proportions cannot compare with the grandeur of our city. To feed it every day, thousands of individuals devoted to the service of its gullet voluntarily condemn themselves to continual labor. For Paris, in the year 1844, five slaughterhouses killed and carved up: 76,481 steers, 16,374 cows, 77,881 calves, 437,385 sheep, 90,000 hogs. Such is its appetite!

The small bites, pâtés, terrines, preserved meats, crawfish and lobster, delicacies that Paris eats for its pleasure as horsd’oeuvres, to add charm to its leisure and sharpen its appetite, constitute a weight of 112,000 kilograms. The local meats, small gifts that come from the surrounding area, contribute only 821,000 kilograms to its diet; sausages and cold cuts play a more important role there, Paris consuming some 3,418,000 kilograms, sufficiently warranting the burning thirst by which it is constantly tormented. There are also the extremities and the offal; these are the leftovers from the butchering that reaches just about 1,240,779 kilograms. Such are the principal elements of the animal part of its nutritional diet.

The other amenities of its table are not any less than those of which we have just spoken.

The poultry and game, the butter, the oysters, the seafood, the eggs, the cheese consumed annually by Paris are worth twenty-five million francs: ten million for the poultry and game alone, eight million for the fish and the oysters, five to six million for the eggs, close to one and a half million for the cheeses.

In 1845 Paris consumed more than a million hectoliters of wine; about 115 liters for each resident. This quantity is for real wine, introduced legally into Paris; but who will say how much it was extended by fraud and processing. The committee for viniculture estimates water sold for wine at 500,000 hectoliters. This is still only a probable figure.

Image credit: Illustration by Bertall (Charles Albert d’Arnoux) featured in Paris à Table. Please do not reuse without permission.

Image credit: Illustration by Bertall (Charles Albert d’Arnoux) featured in Paris à Table. Please do not reuse without permission.In addition, Paris drank 119 hectoliters of beer and 14,000 liters of apple and pear cider. Alcoholic spirits contributed to its consumption 36,000 hectoliters, which include, admittedly, liqueurs and fruit brandies, perfumed waters, alcoholic varnishes, and pure alcohol in barrels. We think that four-fifths of this quantity should be allocated to consumption down the gullet.

Recalling that grapes alone account for 623,962 kilograms will give some idea of the fruit eaten here. Let us not forget to mention that every year Paris puts into its salads 18,000 hectoliters of vinegar and therefore three times as much oil.

The provinces surrounding it supply its vegetables, coming from more than two hundred kilometers all around: it enlists the entire French countryside. Provence is its greenhouse; Touraine its garden; Normandy raises and fattens its cattle; the flocks of sheep destined for its table graze in the robust meadows salted by the ocean’s waters and along the aromatic crests of the Ardennes; it fishes in three seas; like no other, it is rich in rivers, streams, lakes, and ponds; it holds within its waters the fish most in demand; in its torrents, the ponds of its mountains, it sees trout multiply; at the mouths of its rivers, it finds salmon, sturgeon, and those hybrid species, whose time in fresh water, close to the sea, endows them with such delicate flavors. Its forests and woods do not let it lack for game; those bands of riflemen, those panting hounds, those stallions and hunters surge forth for Paris; the horns sound out for Paris. It counts among its purveyors the most illustrious of names: there have been kings, and there are still princes who kill game for it.

Who will count the number of people who put something in the oven and take it out every day for Paris: cooks, grill men, bakers of pastry and bread, cupbearers, confectioners, cheese and dairymen, ice-cream makers; those who watch over the saucepans, the kitchens, the spits, the service, the ovens, the cellars and liquor cabinets, and those who preside over the fruits and buffets; who then will undertake the census for all this?

The Paris kitchen requires the use of more than 2,773,000 hectoliters of charcoal, not including 98,000 hectoliters of coal dust, separate from the coal itself used more and more for this purpose. Today more than two million hectoliters of that last fuel are consumed.

In every corner of the world, Paris has people mindful of its tastes, its fantasies, its desires, its whims; if its appetites languish, they work to revive them, they think about generating new ones in place of those that have gone away; imagination, art, and industry are united in this competitive rivalry to win the good graces of the master. Paris has thus become the only place where the magical power of gold has been applied to its fullest extent: with gold, Paris knows nothing is impossible.

Elsewhere, greater pomp and greater magnificence can be deployed; but nowhere can the exquisite delicacy of taste and elegance be satisfied as well as in Paris; Parisian comfort does not have the refinements of egoism; but it has the understanding of a life that blends the delights of the mind with the satisfactions of the sensual. This charming secret, whose tendencies are on full display and which retains the natural graciousness of its customary manners, is, for all measures of its existence, an inexhaustible source of attractions, and a privilege belonging to Paris alone; it is envied, it is copied; but it cannot be stolen away.

At the table is where Paris loves to assemble those riches that shape its pride and its happiness.

Featured image credit: Illustration by Bertall (Charles Albert d’Arnoux) featured in Paris à Table. Please do not reuse without permission.

The post Paris in Translation: Eugène Briffault’s Paris à Table [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

April 17, 2018

2019, the year of the periodic table

The periodic table turns 150 next year. Given that all scientific concepts are eventually refuted, the durability of the periodic table would suggest an almost transcendent quality that deserves greater scrutiny, especially as the United Nations has nominated 2019 as the year of the Periodic Table.

These days it seems that physics gives a fundamental explanation of the periodic table, although historically speaking it was the periodic table that gave rise to parts of atomic physics and quantum theory. I am thinking of Bohr’s 1913 model of the hydrogen atom and his extension of these ideas to the entire periodic table. The Bohr model can only cope quantitatively with one-electron systems, and yet using a mixture of chemical and spectroscopic intuition, Bohr succeeded in stating the electronic configurations of many different atoms.

Soon afterwards, Pauli postulated that electrons possessed a “classically non-describable two valuedness,” which at the hands of others became misleadingly known as “spin.” The electron does not really spin, but has an intrinsic magnetism that is not attributable to any mechanical motion whatsoever.

Remaining for a further moment on the physics of the periodic table, one should also mention Schrödinger, and the wave-nature of the electron. It is a remarkable fact that by solving his wave equation for the hydrogen atom, Schrödinger found that three quantum numbers were required to specify the possible solutions. When Pauli’s fourth quantum number was added to these three it became possible to explain the overall structure of the periodic table. As is well-known, the possible lengths of the periods in the table—namely 2, 8, 18 and 32—come from the possible ways to combine the four quantum numbers for each of the electrons in an atom. This in turn suggests a further vindication of Prout’s hypothesis, postulated over 100 years earlier, that all the atoms are composites of the hydrogen atom.

Now let me now turn to chemistry and pick up the story. A little after Prout proposed his simple idea, Döbereiner discovered the first few examples of triads of elements whereby one of a group of the three elements has the average atomic weight among the three. This suggested an underlying regularity that connected completely different atoms.

The very existence of triads rests on nothing but chemical periodicity, the notion that approximate repetitions occur after regular intervals in an ordered sequence of elements. For example, the reason why chlorine, bromine, and iodine form a triad is the fact that there are an equal number of elements situated between chlorine and bromine as there are between bromine and iodine. It could almost be said that Döbereiner discovered periodicity 50 or so years before Mendeleev.

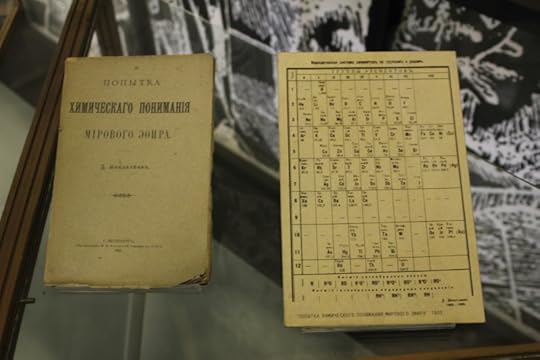

Many questions continue to be debated concerning Mendeleev’s 1869 discovery of the chemical periodicity, including whether he was the only discoverer. My personal view is that discoveries occur in a gradual evolutionary fashion and that they frequently occur in many places almost at once. The periodic table was independently discovered by at least six individuals over a period of seven years between De Chancourtois’ telluric screw of 1862 and Mendeleev’s mature periodic table of 1869.

Image credit: “D. Mendeleev’s Periodic table from his book” by Newnoname. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: “D. Mendeleev’s Periodic table from his book” by Newnoname. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons.A surprising feature of the periodic table is the extent to which many aspects of it are still unresolved. There is little agreement as to what its optimal form should be, or indeed whether an optimal form even exists. The almost ubiquitous version is the 18-column wide table that displays the f-block elements as a kind of disconnected footnote. Some of us believe that the f-block is better shown incorporated into the main body of what now becomes a 32-column table.

A more radical alternative consists of the left-step table as first proposed in the 1920s by the French engineer Charles Janet. In this table, helium is relocated to the top of the alkaline earth elements on the basis of its having two electrons and so being analogous to elements that possess two outer-shell electrons. A second modification consists in moving the entire s-block, including helium, to the right hand edge of the table. This left-step table now shows every single period length as repeated, by contrast with the more traditional tables in which the first very short period of two elements appears just once. The new sequence of period lengths in the Janet table becomes, 2, 2, 8, 8, 18, 18, 32,32, a more mathematically regular sequence that is also more consistent with the Madelung rule that summarizes the order of orbital filling.

But the Madelung rule itself is a matter of some controversy since, for any given element, the rule only provides the order of filling for the s-block elements. On the other hand, the Madelung rule does genuinely yield the order of orbital filling as one moves through the periodic table, barring 20 or so anomalies starting with the atoms of chromium and copper.

The periodic table has endured many challenges in the course of its development. The first major crisis took place when the noble gases were first discovered at the turn of the 19th century. It first seemed as though there were no places to house these unexpected elements. Similarly, the sudden proliferation of isotopes seemed to pose a major problem for the periodic table. Both of these problems were successfully resolved. The noble gases were housed in a new column that is placed at the right hand edge of the table, at least in the conventional formats. In the case of isotopes, it was realized that the identity of elements was captured by the number of protons in the nuclei of their atoms or their atomic number. Separate isotopes of any particular element did not have to be separately displayed on the periodic table given that they share the same atomic number.

However, not all is well in the world of the periodic table. First, it is incomplete in a literal sense that new elements are continually being synthesized and taking their place at the table. Secondly, nobody knows where the periodic table will end. Some predict it will end with element 127 on the basis of a simple argument from relativity theory, while other more sophisticated calculations point to a higher value of 172 or perhaps 173.

Thirdly, and perhaps most serious of all, there is the looming threat of modifications to the behavior of atoms due to relativistic effects which cause some elements not to behave in the way that one might predict from the group that they fall in. If this trouble persists it may yet destroy the central tenet of the periodic table, namely the approximate repetition in chemical properties after regular intervals.

Featured image credit: “Air Force photo” by Margo Wright. Labeled for reuse with modification via Tinker Air Force Base.

The post 2019, the year of the periodic table appeared first on OUPblog.

Reverse-mullet pedagogy: valuing horror fiction in the classroom

Are you familiar with the mullet? It’s a distinctive hairstyle—peculiarly popular in continental Europe in the 1980s—in which the hair is cut short on the top and sides but left long at the back. Whatever the aesthetic gravity of the mullet, it comes with a philosophy. The philosophy of the mullet is this: “Business in the front, party in the back.” I’ll argue that the reverse holds true for the horror genre, didactically speaking.

Horror fiction is sexy. Horror has zombies. It has ghosts and vampires. It has Hannibal Lecter and Jigsaw, Michael Myers and Jason Voorhees, Freddy Krueger and Leatherface. It has cannibal hillbillies and crazed college kids. The genre brims with iconic content. Even folks who have never seen a horror film will have a distinct impression of the genre’s iconography. That’s because horror is uniquely suited for capturing our attention and sparking our imagination—we’re prey animals, keenly attuned to dangers in our environments, including our imaginative environments. The elements of horror simply hijack our minds, and that makes the genre well-suited for educational purposes—because it’s more than vampires and slasher villains and cannibal hillbillies.

For horror fiction as subject matter in higher education, the maxim is this: “Party in the front, business in the back.” The genre captures students’ attention, but underneath its bloody and monstrous (and often ridiculously far-fetched) exterior it brims with significance. A work of horror is a portal into reflections on, and scholarly discussions about, substantial topics within aesthetics, philosophy, psychology, history, theology, linguistics, politics, and the list goes on. It’s like a didactic Trojan horse. Students think they’re having fun with slasher killers and vampire apocalypses—and they are, but they’re also engaging with real topics, real theory, real substance. Let me illustrate the idea with some examples from one of my favorite horror novels, Richard Matheson’s vampire story I Am Legend from 1954.

For horror fiction as subject matter in higher education, the maxim is this: “Party in the front, business in the back.” The genre captures students’ attention, but underneath its bloody and monstrous exterior it brims with significance.

In I Am Legend, we follow the lone survivor of a vampire pandemic, Robert Neville. Neville has fortified his house against vampire attack and spends his time not only trying to survive, but to find meaning in a bleak world that seems to be stripped of meaning. As he muses, he is “a weird Robinson Crusoe, imprisoned on an island of night surrounded by oceans of death.” Eventually, he meets another survivor, Ruth, but she turns out to be a carrier of a mutated vampire germ, sent to spy on him by a new, violent society of infected who keep the germ at bay with drugs. Neville is captured and scheduled for execution, but he takes his own life. There is no place for him in the new society. That’s the basic plot. Sounds pretty exciting, right? There’s an apocalyptic pandemic and violent confrontations with the undead, there’s survival and horror, despair and hope. More than that, though, the story is about the quest for meaning in a radically disenchanted world. It’s about what makes us human. The short novel extrapolates on existential anxiety in the modern world and prompts us to confront tough questions: Why are we here? What’s our place in society? Which norms should we follow, and why?

Neville’s plight engages us because it resonates with basic evolved motives—the motive for survival in a hostile world, and the motive for establishing and maintaining meaningful, reciprocal social networks. Neville is preyed upon, and he is all alone. At one point, visiting his wife’s grave, he wonders about the point of going on: “Still alive, he thought, heart beating senselessly, veins running without point, bones and muscles and tissue all alive and functioning with no purpose at all.” If we’re biological mechanisms dropped into an indifferent world, “bones and muscles and tissue,” then what’s it all about? It’s about social connection, it’s about family. The human central nervous system evolved to connect with other human nervous systems, the brain evolved to connect with other brains. At another point in the novel, Neville visits an abandoned library in search of science books (he’s trying to figure out the cause of the vampire outbreak). He envisions a “maiden librarian” setting the library in order for the very last time:

“To die, he thought, never knowing the fierce joy and attendant comfort of a loved one’s embrace. To sink into that hideous [vampire] coma, to sink then into death and, perhaps, return to sterile, awful wanderings. All without knowing what it was to love and be loved. That was a tragedy more terrible than becoming a vampire.”

The novel only ends when Neville realizes that there can never be a place for him in the new society. No meaningful social connections, no family. That’s when he ends his life, realizing that at least he, ironically, lives on as a terrifying legend in the mind of the infected.

I’ve taught I Am Legend many times, and in my experience, students really like the novel. They’re drawn in by its high premise, by the drama and the vivid depictions of horror. They’re taken with its stylistic elegance, moved by its penetrating portrait of its tortured protagonist. They are fascinated with the vampires and the post-apocalyptic scenery. But they also resonate to its meaning, its connotations. The novel allows students to engage in discussions about literary meaning, about contextual analysis—the novel is very much a product of its time, with the existentialist anxiety and the Cold War terror of global destruction—and about morality and psychology. We discuss genre—is it horror or sci-fi, or both?—and literary form; for instance, how Matheson builds empathy through free indirect discourse, which gives the reader crucial access to Neville’s thoughts and emotions. We talk about the meaning of it all, life and horror and literature. That is party in the front and business in the back.

Featured image credit: Hands by simonwijers. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Reverse-mullet pedagogy: valuing horror fiction in the classroom appeared first on OUPblog.

The life of an activist-musician: Japanese rapper ECD

When the family of the Japanese rap pioneer and activist ECD aka Ishida Yoshinori announced on 24 January 2018 that he had passed away, the music and activist worlds let out a collective sigh of mourning. Zeebra, Japan’s most commercially successful rapper, cried audibly while honoring him on his radio show. Meanwhile, political theorist Ikuo Gonoi credited his constant presence in demonstrations with creating a “liberal moment” mixing culture and politics. But who was ECD, and what were his contributions to Japanese culture?

Hip-hop pioneer

One of Japan’s earliest rappers, ECD performed in the late 1980s as an opening act for Public Enemy, Jungle Brothers, and others when they toured Japan. He released some socially critical songs, like “Pico Curie” (1989, about radioactive fallout from Chernobyl), “Racist,” (1993, about racism), and “Lonely Girl” (1997, ft. K Dub Shine), about young women who date older men for money to buy luxury-brand goods (enjō kōsai).

But he was most remembered for organizing Thumping Camp, the first large-scale hip-hop festival in Japan, on July 7, 1996. It was a showcase for underground hip-hop, as opposed to the idol-pop-inspired J-Rap that was climbing the charts.

Sound demos against the Iraq War, 2003–2004

The Japanese held many street protests in 2003 against the American War in Iraq. ECD was on the organizing committee of Against Street Control (ASC), a group that put together a series of “sound demos” or street demonstrations featuring trucks with sound equipment, upon which DJs and bands performed. At one sound demo on 19 July 2003, the police arrested several protesters—a big deal in Japan as the police can hold people for 23 days without an indictment. ECD overheard a protester yell, “We’re not the kind of guys who’ll do what they’re told.”

ECD made a song out of this retort, “Yūkoto kikuyō na yatsura ja naizo” (2003), with a backing track based on Japanese singer Shuri Eiko’s “Ie ie” (1967). He describes the riotous atmosphere of the sound demonstration, beating “oil cans . . . for three hours,” and the violence of the police, “hooligans with a bad attitude.” The song became the anthem of the anti-war movement and would resurface a decade later.

[ECD] contributed to the formation of a new style of call-and-response in protests, whereby rappers rapped calls in rhythm over musical tracks, and the beats encouraged the protesters to chant them back.

Anti-nuclear protests after Fukushima accident, 2011–2016

The frightening images of the hydrogen explosions at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant and the lack of credible information caused many Japanese, particularly parents, to worry about health risks from radiation. ECD lent his booming rapper’s voice to lead calls in the weekly (and still ongoing) anti-nuclear protests in front of the prime minister’s office. He contributed to the formation of a new style of call-and-response in protests, whereby rappers rapped calls in rhythm over musical tracks, and the beats encouraged the protesters to chant them back. One such performance was at an anti-nuclear demonstration on July 29, 2012, which attracted over 200,000 protesters. During this demonstration, ECD chanted a twist on his 2003 anthem: “Yūkoto kikaseru ban da, oretachi ga” (It’s our turn to make them listen to what we say).

This line is from “Straight Outta 138” (2012). The rapper Dengaryū had invited ECD to do a guest verse on his song because he liked the hook from ECD’s 2003 song. ECD explained that the political situation had changed. In 2003, the protesters created mayhem to oppose the geopolitical hegemonic order that allowed the Iraq War to happen. The anti-nuclear issue called for a change in domestic policy; one had to act as a citizen and convince lawmakers to act. He therefore transformed his line to be more fitting with the times:

2003: Yūkoto kikuyōna yatsura ja naizo We’re not the type who’ll listen [to authority]

2012: Yūkoto kikaseru ban da, oretachi ga It’s our turn to make them listen to us

In his verse, ECD makes an urgent appeal for citizens to speak up (“If we stay silent, we’ll be killed”), and calls for citizens to “sign petitions, vote, demonstrate.”

Protests against the Abe administration’s policies

The passage of the Secrecy Law in 2013 (which the Japan Federation of Bar Associations and others believed could endanger freedom of the press) and the Abe Cabinet’s reinterpretation of Japan’s peace constitution in 2014 (to allow Japanese troops to be sent overseas) brought an infusion of student leadership into demonstrations. Students Against the Secret Protection Law (SASPL) began holding demonstrations with a sound truck, on which the group’s members rapped call-and-response patterns to hip-hop beats. ECD was a constant presence, leading calls or helping to deal with the police.

SEALD’s rapper Ushida Yoshimasa, known as UCD, liked ECD’s expression of political agency for citizens in the line, “Yūkoto kikaseru ban da, oretachi ga.” UCD morphed the line into “Yūkoto kikaseru ban da, kokumin ga” (It’s time to make them listen to the nation’s people). This captured the fact that the majority of voters opposed reinterpreting or revising the peace constitution.

ECD’s song “Lucky Man” (2015) captures the spirit of the times with its line, “I hurl my protests in front of the prime minister.” It also suggests someone who has come to terms with the ups and downs of his life, with optimism (“the 21st century has only just begun”).

Rest in power

ECD was diagnosed with cancer in September 2016. Even in his weakened state, he still attended demonstrations, crawling out of his hospital bed to sit by the side of the road and cheer on protesters.

ECD was neither the biggest star nor a movement leader, but his presence had a great impact on both fields. He raised underground hip-hop to commercial viability with Thumpin’ Camp. He was on the front lines of social movements, writing protest anthems, inspiring calls, and performing at protests. He inspired younger rappers to be politically engaged. Most of all, his constant and reliable presence at demonstrations—rare among Japanese recording artists—was inspiring and reassuring to many protesters.

A longer version of this article appears in The Asia-Pacific Journal .

Featured image credit: “DJ” by Mark Vletter. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The life of an activist-musician: Japanese rapper ECD appeared first on OUPblog.

April 16, 2018

We can predict rain but can’t yet predict chronic pain

Accurate weather forecasts allow us to prepare for rain, snow, and temperature changes. We can avoid driving on icy roads, pack an umbrella, or purchase sunblock, depending on what is predicted. Forecasting also generates information trustworthy enough to evacuate a city at risk from a category 4 hurricane. Meteorology has come a long way; today satellite data inform sophisticated computer weather models. Unfortunately, the same can’t be said for forecasting chronic pain. In most cases, health care providers can’t anticipate early or accurately enough which patients might develop long-lasting pain.

Does this come as a surprise to you? Surely people with the most severe injury are the same people to develop chronic pain, right? Not so much. Study after study shows this isn’t the case. Chronic pain can result from simple procedures or from minor injuries. Conversely, people can be completely pain-free after a severe accident or major surgery. This paradox is the reason why learning more about acute-to-chronic pain transitions is of such high priority for future research.

Articles recently published in Physical Therapy (PTJ) shed some light on the problem. The influence of fear, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and catastrophizing on pain has been well documented, but Linton et al share new theories on how these psychological factors interact to lead to chronic pain. They sharea fascinating observation: coping strategies that are helpful in the short term continue to be used even when, ironically, these very same strategies maintain the problem in the long term. Their article gives compelling theoretical information that will inspire updated measurement methods and encourage innovation in patient management.

Beneciuk et al investigated the development of persistent pain after seeking physical therapy. This study included measures across multiple domains to predict whether study participants met a standard criterion for having persistent pain at 12 months. These data confirm other research showing that higher levels of pain and pain-associated distress were predictors of persistent pain—but the findings also indicate that the number of other chronic health conditions and having symptoms in other body systems were predictive, too. These findings provide direction for additional research on how an individual’s overall health status may affect his or her vulnerability for developing chronic pain.

Image credit: Photo by American Physical Therapy Association. Used with permission.

Image credit: Photo by American Physical Therapy Association. Used with permission. Predicting chronic pain is a complex task, as highlighted by these articles in PTJ; and, as highlighted by an article in Pain Medicine, there is a role for epigenetics in understanding the transition to chronic pain. These and other articles indicate that future research will need to challenge existing paradigms before we will be able to effectively deliver personalized care for preventing the development of chronic pain. For many years, emphasis was placed on diagnostic testing. Research to date, however, clearly indicates that diagnosis alone does not determine whether chronic pain develops. Instead, it appears that improved prediction of the transition to chronic pain will come from considering a wide variety of factors.

Ongoing research will determine how a chronic pain forecast can be customized through the evaluation of factors such as variability in gene expression, individual pain sensitivity, psychological distress, presence of other health conditions, and socioeconomic status. When all these components are combined and verified to create an accurate forecast, that information could potentially be invaluable to the development of individualized pain management plans.

Knowing an individual’s chronic pain forecast might help avoid overutilization of higher-risk treatments. For example, a long-term forecast indicating that there is low likelihood of chronic low back pain would mean exercise is a better treatment option than opioids or surgery. This long-term forecast would be especially beneficial if the short-term responses to exercise are not favorable and if there is an option to escalate care to include opioids or surgery. An individual could choose to continue with the exercise treatment longer knowing that the back pain is not likely to become chronic.

Conversely, a long-term forecast indicating a high likelihood of chronic low back pain might trigger the delivery of interdisciplinary treatment. Typically, interdisciplinary treatment is an option used only after different individual treatments have failed. However, with individualized predictions, interdisciplinary treatment could be offered much earlier than currently usual, possibly improving the outcomes from this approach.

Accurate weather forecasting has saved countless lives by allowing adequate preparation for severe weather; accurate prediction of the transition to chronic pain will help better direct treatment that improves quality of life—and could even save lives by avoiding the perils of opioid addiction.

Featured image credit: Photo by American Physical Therapy Association. Used with permission.

The post We can predict rain but can’t yet predict chronic pain appeared first on OUPblog.

Impunity for international criminals: business as usual?

The shocking images capturing the atrocities of armed conflicts in Syria have so shocked the world that, in March 2011, the UN General Assembly set up the International Impartial and Independent Mechanism (IIIM) to assist in the investigation and prosecution of those responsible for the most serious crimes under international law committed in Syria. The most serious crimes under international law are generally understood to be acts of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. The international support for the IIIM gained traction after the reported confirmation that chemical weapons had been used in Syria. However, when there was some hope for achieving the all-inclusive political solution for Syria, bringing individual criminal responsibility to account seems to lose its impetus and priority in the eyes of the countries participating in the diplomatic negotiation who fear that prosecution might derail the peace process and perpetuate the ongoing situation in Syria.

Besides, why should the perpetrators of atrocities in Syria be deterred by the prospect of being punished for their crimes? After all, those sought for prosecution before the International Criminal Court (ICC) for similar sins in Darfur, Sudan, have yet to be apprehended. The ICC does not have jurisdiction over Syria unless the UN Security Council refer it to the ICC, and such referral is impossible without the unanimous agreement of the five Permanent Members of the Council, some of whom will certainly veto any proposed referral. Setting up an ad hoc international criminal tribunal, like the one for the former Yugoslavia or for Rwanda, is not a realistic option in the light of such veto in the Security Council.

Nation States can resort to existing international agreements binding on them to either extradite to another party to the agreements persons accused of any offence covered by the respective agreements or prosecute the persons in their own domestic courts. Most of these agreements concern acts of international terrorism; the others are related to acts of torture, enforced disappearances, and the most serious war crimes known as “grave breaches” committed during international armed conflicts. The existing agreements do not cover acts of genocide, most crimes against humanity, or most war crimes, however.

The most serious crimes under international law are generally understood to be acts of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes.

To curb the impunity loopholes mentioned above, a group of countries led by Argentina, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Slovenia have initiated efforts to supplement supranational justice with the adoption of a new international agreement on mutual legal assistance and extradition concerning the effective national investigation and prosecution of perpetrators of all the major international crimes. It will take several years for the agreement to be concluded and come into effect, if at all. All hope is not lost though; there is evidence of practice by nation States accompanied by their sense of binding legal obligations to substantiate the existence or at least crystallization of a rule of customary international law binding upon all of them to extradite or prosecute perpetrators of the most serious international crimes.

Two considerations may impede bringing wanted criminals to criminal justice. First, incumbent heads of State, heads of Government, and foreign ministers have immunity from prosecution in foreign domestic courts so long as they remain in office; when they have left office they have no such immunity for acts done in their private capacity or, arguably, crimes of international concern committed by them. Therefore, these office holders are usually motivated to “fight to the death” rather than peacefully cede power unless a deal is struck to grant them a blanket amnesty for their past wrongs. Second, a nation may opt for national reconciliation instead of mass prosecution of hundreds of thousands who have committed atrocious acts against their fellow compatriots—as in the case of post-apartheid South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Truth commissions are normally entrusted with investigating and documenting atrocities, identifying the perpetrators of atrocities and involving them in a process of public assumption of their individual responsibilities, providing redress to victims of mass atrocities, and making recommendations for reform and establishing a mechanism to ensure accountability for future atrocities. Yet, the work of some truth commissions, such as the ones in Argentina, Chile, and Peru, facilitated national prosecution of perpetrators of crimes. The Integral System of Truth, Reparations, Justice, and Non- repetition under the 2016 peace accord to end several decades of internal armed conflicts in Colombia includes a truth commission entrusted with examining the broader truth of what happened in the armed conflict, and why, beyond the facts and responsibilities of particular crimes. There will be no amnesty for crimes against humanity, war crimes, genocide, or serious international human rights crimes such as extrajudicial executions, forced disappearances, torture, sexual violence, forced displacements, and recruiting or using child soldiers. While an amnesty may be granted for rebellion and related political crimes as well as other crimes inherent in the act of armed rebellion, this is without prejudice to the victims’ right for any damages caused by those crimes.

The Colombian approach seems to be fairly balanced and should be emulated elsewhere. Above all, there can be no “impunity” as usual for perpetrators of international crimes, especially those in the leadership position.

Featured image credit: “The Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands, which is the seat of the International Court of Justice” by Yeu Ninje. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Impunity for international criminals: business as usual? appeared first on OUPblog.

April 15, 2018

Women artists in conversation: Zoe Buckman [Q&A]

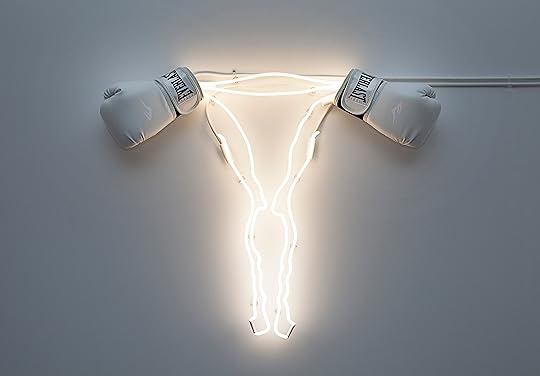

Zoe Buckman is a young artist and activist whose work in sculpture, photography, embroidery, and installation explores issues of feminism, mortality, and equality. She was born in London in 1985 and lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. Buckman was a featured artist at Pulse Projects New York 2014 and Miami 2016, and was included in the curated Soundscape Park at Art Basel Miami Beach 2016. Her new public work, Champ, produced in collaboration with the Art Production Fund, is located on the corner of Sunset Boulevard and Sweetzer Avenue in front of The Standard in West Hollywood. Standing 43’ tall and 9’ in diameter, the installation features a glowing white neon outline of an abstracted uterus with fiberglass boxing gloves in place of ovaries. The kinetic sculpture slowly rotates, serving as a symbol of female empowerment, and will be on view until February 2019. Buckman also recently opened “Let Her Rave,” a solo show of her work at Gavlak Gallery in LA.

In an interview with Kathy Battista, Editor in Chief of the Benezit Dictionary of Art, Buckman discusses her work, her passion for health care rights for all women, and her new public art project.

Kathy: Feminism has recently become fashionable again after a few decades where it had a bad reputation. In the past decade we’ve seen feminist art take central stage in exhibitions such as WACK!, Global Feminisms and Radical Women . We also see feminist iconography and messaging in popular culture and fast fashion slogan t-shirts. Can you comment on the recent pervasiveness of feminism? Does this intersect with your work?

Zoe: Because both of my parents are feminists, and because my mum, in particular, is an activist—I feel gender inequality has always been a part of my dialogue. It has been really amazing to witness how feminism has become part of our social landscape, and like many of us, I just hope we’re not in the midst of fad.

“Champion“ from the exhibition Mostly It’s Just Uncomfortable, neon light and boxing gloves, 2015 by Zoe Buckman. Image courtesy of the artist.

“Champion“ from the exhibition Mostly It’s Just Uncomfortable, neon light and boxing gloves, 2015 by Zoe Buckman. Image courtesy of the artist.K: You are about to launch a new public installation at The Standard in Los Angeles. Tell us about Champ : how does it relate to its site at a hotel and in such a prominent location?

Z: This will be my first large-scale public sculpture! One of the most exciting things about this project is the visibility. The piece will be up for a year on one of the city’s most heavily trafficked Boulevards. What I find most moving about this opportunity is when I think about how it will have the chance to transcend the exclusivity of the art world and will be seen by many: from children to bus drivers, Hollywood execs, to the hotel staff.

K: You made Mostly It’s Just Uncomfortable (2015) in response to the US government’s current agenda to curb funding for Planned Parenthood. You come from a country that offers health care to all its citizens and residents. Can you say something about your interest in health care for all and how this is of particular importance to women?

Z: I was raised to believe that access to health care is a basic human right and that the country one lives in should provide this service for free. It’s been really difficult for me as a Londoner to adjust to the systems in place in the US. I’ve lived in New York for over a decade. In the run-up to all three elections I’ve witnessed, male politicians start making statements about abortion and choice, which almost always leads to a discussion about rape. The UK has its problems, but no one discusses abortion there anymore. It’s legal and free and women are offered free counselling on the NHS should they opt to terminate a pregnancy… because the country recognizes that that decision is always a difficult one to arrive at for any woman, and that women deserve support through that process. Not only does the perpetuation of these judgmental and backwards statements bother me, but women’s rights are constantly in flux here. The laws concerning women’s sexual health seem to be ever-changing state-by-state and constantly threatened.

“Head Gear” from the exhibition Mostly It’s Just Uncomfortable, speculums and powder coated metal, 2017 by Zoe Buckman. Image courtesy of the artist.

“Head Gear” from the exhibition Mostly It’s Just Uncomfortable, speculums and powder coated metal, 2017 by Zoe Buckman. Image courtesy of the artist.K: I’m interested in Every Curve , where vintage garments typically associated with the feminine—bras, stockings, knickers—are hand embroidered with hip-hop lyrics. As a feminist and a lover of hip hop, I’m often asked about the treatment of women in certain artists’ lyrics, so this work speaks volumes to me. Can you talk about how you selected the lyrics by Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G. and the garments, and why you were drawn to antique pieces in particular?

Z: I wanted to put the lyrics of these two murdered rappers and their statements about women (both the empowering and degrading) into the context of the history of objectification and sex. In order to really look at the how ideas about the female form have developed throughout history, I decided to look at lingerie because it is intimate and personal by nature, but also speaks to the male gaze. I wanted to invoke the female form without explicitly using it (because it’s over-used in art!) so embroidery on under garments felt right for this series.

K: Your use of wedding dresses as artistic material, combined with boxing gloves, calls to mind the strategies and themes of second wave feminist artists including Judy Chicago and Kate Walker, as well as earlier artists such as Frida Kahlo . Can you tell us why you chose to use wedding dresses?

Z: The series Let Her Rave is a response to a line in a Keats poem, but is also a comment on marriage as a social construct that keeps women hemmed in… even if we are complicit in this. I wanted to look at ideas of chastity, purity, and perfection, and how these are shackling concepts. Nothing says “perfection” with more weight than a wedding dress, so acquiring used wedding dresses and cloyingly imprisoning boxing gloves with them was the way I wanted to speak to these issues.

“10 Months in this Gut” from the exhibition Every Curve, embroidery on vintage lingerie, 2015 by Zoe Buckman. Image courtesy of the artist.

“10 Months in this Gut” from the exhibition Every Curve, embroidery on vintage lingerie, 2015 by Zoe Buckman. Image courtesy of the artist.K: Do you see fashion as a feminist statement?

Z: For me, Feminism is all about choice. Can I choose who I love? If I want to have children? If I want to work? How I want to dress? If women want to embrace fashion then, yes: their clothing choices are part of their feminist statement. If dressing is merely a means to an end for a woman and she cares little about “fashion,” then that is wonderful too. I personally really enjoy the aesthetic quality to clothing and so fashion is one of the ways I choose to express myself.

K: Do you have plans to continue to work as both a feminist artist and activist? Are there any projects on the horizon?

Z: Yes to all! My next project will be to spend more time in London with my Mum, because I am being made to realize how precious my time is. Activism and service will come into everything I do, and on the work front I’m excited to develop my first museum installation with ICP Museum. That will hopefully be shared in the fall or next year.

Featured image credit: “Champ” by Zoe Buckman (2018). Photo by Veli-Matti Hoikka, courtesy of Art Production Fund. Used with permission.

The post Women artists in conversation: Zoe Buckman [Q&A] appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers