Oxford University Press's Blog, page 263

April 11, 2018

The real price of legitimate expectations

In early February 2018, the British Legal Aid Agency (LAA) agreed to provide funds to the families of people killed in the 1982 Hyde Park bombing as they pursue a civil lawsuit against the main suspect in the case, John Downey.

How did this situation come about, and why isn’t Downey being prosecuted under the criminal law? The answers lie back in 2014 when a criminal case against Downey at the Old Bailey collapsed and was dropped.

In the context of the Good Friday Agreement, the Police Service of Northern Ireland wrote to Downey—and other so-called “on the runs”—stating that it was not aware of any interest in him either by itself or by any other police force in the United Kingdom. In fact, this statement was incorrect: he was wanted by the Metropolitan Police in relation to the Hyde Park bombing.

During the Old Bailey trial, Mr Justice Sweeney reasoned that because of the “comfort letter” Downey received, he had legitimate expectations of not being arrested, not losing his freedom for a time, not having strict bail conditions, and not being put at risk of conviction for very serious offenses. So when the Metropolitan Police arrested Mr Downey at Gatwick Airport in May 2013, they frustrated these expectations. In the words of Mr Justice Sweeney, “the defendant was wholly misled.”

Such cases raise deep questions about the relationship between the state and citizens. But it is not just individual citizens whose legitimate expectations can be frustrated by government departments.

R (Luton Borough Council and others) v Secretary of State for Education, for example, centred on a decision taken by the then Secretary of State for Education, Michael Gove, to scrap the Building Schools for the Future (BSF) programme. Five local government councils sought judicial review of the decision. Mr Justice Holman ruled in favour of the councils on the question of whether or not Mr Gove’s decision had frustrated their procedural legitimate expectations; he characterized Gove’s decision-making process “as being so unfair as to amount to an abuse of power.”

When administrative agencies of government make promises or assurances to citizens or other non-governmental agents, should they always be held to those promises? What if the promises concern terrorist suspects? What if the promise concerns hundreds of thousands of pounds of funding for building projects?

I believe that administrative agencies of government need not always honour the legitimate expectations they are responsible for having created, because sometimes, doing so is not in the public interest.

Should decisions about the pursuit of retributive justice or urgent decisions about the use of public funds be bound by previous government promises?

Should the democratic will, insofar as it is expressed through the decisions of governmental administrative agencies, bend to the rule of law?

I believe that administrative agencies of government need not always honour the legitimate expectations they are responsible for having created, because sometimes, doing so is not in the public interest.

However, I also propose that, precisely because of their responsibility for having created legitimate expectations, the relevant agencies should at least pay compensation to agents whose expectations have been frustrated. I have in mind compensation that covers damage to reliance interests and associated losses caused by the frustration.

So Downey’s Old Bailey trial should not have been abandoned, but at the same time, he should have been able to claim compensation for any losses he suffered directly as a consequence of having been misled. Because he was routing through Gatwick airport to go on holiday when he was arrested, for example, he should have been allowed to claim for the costs of the holiday he could not take.

In that scenario, Downey could claim for reliance losses but the families would at least have the comfort of knowing that he would also face criminal justice.

What is more, I believe that a legal regime in which governmental administrative agencies have leeway to frustrate legitimate expectations in the name of the public weal, so long as they pay adequate compensation, can be grounded in norms and values we all have reason to care about.

Among these values are: good administration, trust-building, making credible commitments, minimizing the pain of frustration, the rule of law, and treating agents with equal concern and respect.

That the executive branch should not enjoy unfettered or absolute discretion to change policies is part and parcel of the ideal of constitutional democracy.

Featured image:”Old Bailey 2012″ by Tbmurray. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post The real price of legitimate expectations appeared first on OUPblog.

April 10, 2018

In defense of beating dead horses: probing a subtle universe

A February 2017 Workshop on Robustness, Reliability, and Reproducibility in Scientific Research was sponsored by the US National Science Foundation (NSF). The workshop was part of NSF’s response to growing concerns in Congress triggered by increasing media coverage of an apparent lack of reproducibility among findings, especially in clinical sciences. The participants, spanning diverse scientific subfields, were charged to assess the extent of any problems of reliability and reproducibility, and to formulate next steps toward solutions.

The breadth of expertise among participants afforded opportunities to learn, and explore prejudices, about each other’s subfields, while probing the nature of reproducibility problems in sub-disciplines at different maturity levels. Much of the time was spent in small groups to discuss aspects of the broader issue. One such group focused on the role of theory in guiding experimental research and identifying non-robust results. A prominent experimentalist in soft condensed matter physics broke the ice by opining that theory was largely irrelevant to his research. He was following his nose to discover breakthrough phenomena or new materials with potentially important applications. In that approach, what might appear as irreproducibility among experiments by different groups often just reflects variability arising from not-yet-recognized dependences on some experimental conditions. Attempts to resolve these discrepancies promote understanding of the conditions and dependences.

I pointed out that in nuclear and particle physics we were at a quite different stage, with well established, if not always complete, theories and an extensive experimental database to build upon. Experiments to confirm or find flaws in those theories have the potential to unveil profound new physics. But experimenters who produce results that are real outliers from theoretical predictions or previous measurements have “a lot of ‘splainin to do” before the broader community will take the new result seriously. A prominent irreproducible result in these fields occurred in September 2011 when the OPERA Collaboration reported apparent evidence that neutrinos travel faster than light. That result would have violated the fundamental postulate of Special Relativity and seemed inconsistent with the earlier observation that neutrinos from supernova SN1987A were detected on Earth at nearly the same moment as the light from that stellar explosion. Widespread skepticism was validated when the OPERA experimenters later traced their spurious result to a faulty fiber optic cable in their setup. Identifying inadvertent mistakes is part of the self-correction embedded in the scientific method.

This example prompted a provocative question from my sparring partner:

“Why is anyone still interested in doing nuclear or particle physics? The answers already seem known. The Higgs boson discovery completed your Standard Model. Opportunities to discover real breakthrough phenomena seem slim. You folks spend inordinate amounts of time, energy and money redoing experiments that have already been done many times. Aren’t you beating dead horses?”

In response I explained that ours is a subtle Universe. The fact that there is any matter in it at all seems to rely on some mechanism that disrupted an exact early balance between quarks and antiquarks in the infant Universe by a part per billion. This mechanism violated fundamental symmetry principles in ways that our currently accepted theories cannot yet explain. The residual matter is able to produce the energy and the elements essential for life only because the down quark is just enough more massive than its up quark partner, a mass difference parametrized but not explained by current theories. The agglomeration of matter into galaxies and galaxy clusters seems to have relied on attractors comprising dark matter, whose existence we infer from indirect observation of its gravitational influences, but whose nature we do not understand. The Universe’s longevity and accelerating expansion appear to be assured by an unknown source of dark energy that would have been utterly negligible in comparison with radiation and matter in the infant Universe, and that is mind-bogglingly smaller in magnitude than theoretical expectations.

The horses of which he spoke aren’t dead. We’re using our shovels not to beat them, but to keep digging so they don’t get buried alive. Jim Cronin and Val Fitch won a Nobel Prize for discovering that so-called CP symmetry is broken at the 0.2% level in kaon decays, when a previous experiment had placed only an upper limit of 0.3% on that violation. It paid to keep digging. But this violation, now incorporated in the Standard Model, is still wholly inadequate to explain the matter-antimatter asymmetry in the Universe. So nuclear and particle physicists keep digging to unveil other sources of CP violation, for example, via tiny differences in behavior between neutrinos and anti-neutrinos or a tiny spatial separation between positive and negative electric charge inside the neutron, or in the virtual particle-antiparticle cloud surrounding an electron. Clever experimentalists, undaunted by 60 years of null results, continue to find innovative ways to improve the sensitivity of previous experiments by orders of magnitude.

Previous experiments have failed to observe even a single proton decaying, demonstrating that the proton’s lifetime is at least 23 orders of magnitude longer than the age of the Universe. But it’s still worth searching with improved sensitivity for this “forbidden” decay because theories predicting the unification of strong, weak and electromagnetic forces in the earliest instants of the Universe require protons to be not perfectly stable. Similarly quixotic searches under way for an exceedingly rare, exotic decay mode of some nuclei have the potential to establish that neutrinos are their own antiparticles, adding plausibility to speculative suggestions that as yet undiscovered very heavy neutrinos played essential roles in creating the Universe’s matter-antimatter asymmetry. Particle physicists are exploring many avenues to reveal the microscopic nature of dark matter and additional features of dark energy. We keep digging in order to understand the subtle mechanisms by which our Universe evolved.

Some of the profound open questions about our subtle Universe surround the Planck Survey map of tiny fluctuations in the temperature of the relic cosmic microwave background (CMB) arriving at Earth from different directions in the sky. From maps such as these we have gained much of our quantitative characterization of an early Universe we are still far from understanding. Credit for the CMB map: Planck Collaboration, Astronomy & Astrophysics 594, A1 (2016), reproduced with permission © ESO.

Some of the profound open questions about our subtle Universe surround the Planck Survey map of tiny fluctuations in the temperature of the relic cosmic microwave background (CMB) arriving at Earth from different directions in the sky. From maps such as these we have gained much of our quantitative characterization of an early Universe we are still far from understanding. Credit for the CMB map: Planck Collaboration, Astronomy & Astrophysics 594, A1 (2016), reproduced with permission © ESO.Science progresses with a wide spectrum of practitioners, from intrepid explorers who go only where there are no maps, to meticulous craftspeople who design exquisite experiments searching for tiny loose threads that, once pulled, may unravel large portions of what we think we already know.

Featured image credit: ‘The boy lost in the woods’ by Guillaume Jaillet. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post In defense of beating dead horses: probing a subtle universe appeared first on OUPblog.

What causes oral cancer and how can we prevent it?

We know that excessive consumption of alcohol is detrimental to oral health, but why? We know that tobacco smoking, alcohol, and poor oral hygiene cause increased acetaldehyde levels in saliva. Alcohol itself is not carcinogenic, but it is metabolised to acetaldehyde which has been strongly implicated in the development of oral cancer. The variation between people in how they metabolize alcohol might explain why some are at greater risk of cancer than others. It is not just the amount of alcohol that is consumed, though this is important, but the genetic factors that control the way that alcohol is metabolized in that individual.

The oral microflora is capable of producing toxic acetaldehyde in greater quantities than is present in the cells of the oral mucosa. At first, this might seem confusing because poor oral hygiene is a weak risk factor for oral cancer in the general population. Poor oral hygiene and the oral microbial production of acetaldehyde may have a much more significant carcinogenic role in those who drink alcohol excessively. Heavy drinking and smoking will increase the microbial acetaldehyde production and this may explain the synergistic effect of both factors in causing oral cancer.

How do we put this knowledge into practice?

Patients who are heavy drinkers and smokers need to receive preventive counselling. Healthcare professionals need to be vigilant to the early signs of oral cancer. In 2014, there were 7,603 cases of mouth cancer in the United Kingdom. You might expect that with increasing living standards and better health awareness, this figure would be falling over time. The opposite is true; in fact, the incidence of mouth cancer has increased over the last decade. Squamous cell carcinoma could be identified much earlier than at present. Earlier diagnosis would mean less disfiguring surgery and a dramatically improved chance of survival for patients affected. The delay happens with patients failing to seek professional help and then doctors and dentists failing to recognise this potentially fatal disease.

Cigarette, smoke by realworkhard. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

Cigarette, smoke by realworkhard. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.The diagnosis of oral carcinoma

Not every ulcer is cancerous, of course, and most ulcers can be treated successfully by removal of any obvious local cause. The dentist’s suspicion should be alerted, however, by finding an ulcer that is failing to heal after 2-3 weeks. This needs urgent referral to a specialist for further assessment and investigation. It is advised that every dental examination should include an examination of the extra-oral soft tissues, regional lymph nodes, and intraoral soft tissues.

Previously, normal mucosa can develop cancer but red or red and white patches of the oral mucosa have an increased risk of carcinoma or show severe dysplasia. The most commonly affected intra-oral sites are the side of the tongue and floor of the mouth. The lesion can feel indurated or fixed to deeper tissues. The cervical lymph nodes may be enlarged. Patients do not complain of pain in the early stages of disease.

Bone invasion

Successful treatment of oral squamous cell carcinoma involves removal of the primary tumour and lymph node metastases. Invasion of the jaw bone reduces the prognosis. However, the cancer cells do not directly resorb bone. There is a layer of fibrous stroma frequently present between the tumour and bone which produces a protein that induces the bone resorption. In many cases, cancer-associated fibroblasts are seen penetrating bone ahead of the tumour front, which implies that they are important in disease prognosis. A vicious circle ensues with growth factors released from the resorbing bone promoting further tumour growth. Future research will target the fibrous stroma cells as their role seems to be crucial in determining the rate of bone invasion.

“The best way to avoid oral cancer is to not smoke or chew tobacco products and to consume alcohol in moderation.”

Preventing oral cancer

The best way to avoid oral cancer is not to smoke or chew tobacco products and to consume alcohol in moderation. Maintaining good oral hygiene and regular visits to the dentist for a cancer screen are also important, but there may be other significant factors involved in some patients. Did you know that continuous exposure to strong sunlight can induce cancer of the lower lip? The incidence is higher in some professions, for example older male farmers, where they have been exposed to cumulatively high doses of ultraviolet light. The solar radiation, combined with a fair skin, causes DNA damage in the lip. The lower lip is more frequently affected than the upper lip due to its greater exposure to solar radiation. Patients can prevent cancer in the lower lip by using sunscreen, while dentists should be suspicious of lumps, changes in colour or non-healing ulcers on the lower lip.

In summary, the improvement of existing oral cancer treatments is dependent on unravelling the underlying causative mechanisms, such as aldehyde production from excessive consumption of alcohol and smoking. Healthcare professionals can do much to increase their patients’ awareness of cancer risk and can give brief advice to help patients reduce their smoking and use of alcohol. Early recognition of disease and treatment improves the prognosis. Radiotherapy is often considered with small, surgically inaccessible tumours (for instance, at the base of the tongue), as palliative treatment of the larger tumours or where a good functional outcome from reconstructive surgery is unlikely. The general dentist can do much to improve the quality of life of these patients by providing careful management.

Featured image credit: Bar, neon, sign by Alex Knight. CC0 public domain via Unsplash .

The post What causes oral cancer and how can we prevent it? appeared first on OUPblog.

Resisting doomsday: The American antinuclear movement

An aging TV personality occupies the White House. Representing the Republican Party, he denounces his predecessors for coddling the nation’s enemies. Not long after taking office, he begins rattling nuclear sabers with the country’s most dangerous nuclear rival, threatening complete destruction and promising victory in nuclear war. His rhetoric concerns people at home and abroad.

Just as this description applies to Donald Trump in 2017, it also characterizes Ronald Reagan in the early 1980s. A longtime critic of his predecessors’ détente policy, Reagan took a fierce stand toward the Soviet Union. He promised that the communists would end up on the “ash-heap of history,” while members of his administration boasted about the ability to win a nuclear war. Reagan himself refused to make any serious attempt at arms control and instead committed to an enormous buildup of nuclear weapons. Each side provoked the other: the Able Archer NATO exercises, the Soviet destruction of Korean Airlines flight 007, and other Cold War incidents led to the direst nuclear war scares since the Cuban Missile Crisis.

And yet in the face of nuclear doomsday, the American people did not wilt. They did not retreat into fear or powerlessness. Artists, writers, musicians, and filmmakers denounced nuclear weapons. Millions of protesters took to the streets, including Ground Zero Week and the Second UN Special Session on Disarmament, both in 1982. Dozens of states and cities passed resolutions calling for a freeze on nuclear weapons production. African Americans marched to show that nuclear weapons squandered money that could have funded urgent social needs.

Image Credit: 800 women strikers for peace on 47 St near the UN Building, World Telegram & Sun photo by Phil Stanziola via the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: 800 women strikers for peace on 47 St near the UN Building, World Telegram & Sun photo by Phil Stanziola via the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Women blockaded nuclear weapons depots and shaped congressional races. Scientists explained how nuclear war would destroy the global environment while physicians detailed how a nuclear blast would disintegrate the human body. Religious believers practiced civil disobedience while children deluged the White House with angry letters. This resistance movement told Reagan that if he used nuclear weapons, he would never be forgiven.

By 1984, Reagan had made an “about-face,” solemnly stating in that year’s State of the Union address that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.” Reagan’s transformation mimicked other presidential reversals on nuclear weapons. When Dwight Eisenhower said he considered nuclear weapons equivalent to bullets and tested H-bombs at a furious rate, groups such as the Committee for a SANE Nuclear Policy and the Committee for Non-Violent Action protested. By the end of his second term, Eisenhower had paused nuclear testing and pursued a permanent test ban. John F. Kennedy resumed nuclear testing, a move challenged by Women Strike for Peace, and soon he was signing a test ban treaty. Richard Nixon began his tenure by trying to convince North Vietnam he was a nuclear “madman,” but when he tried to deploy antiballistic missiles (ABMs), scientists and NIMBY protesters scotched the plan. In 1972 Nixon signed an ABM treaty with the Soviet Union in order to boost his re-election prospects. In each case, it fell to antinuclear protesters to demonstrate that the president’s initial view of nuclear weapons was morally unacceptable.

These shifts were not inevitable; they depended on ordinary people rising up to defy their leader. It helped that from the start nuclear weapons were stigmatized as morally worse than conventional bombs. Even Harry Truman, not known for sentimentality, recognized this when he halted atomic bombings after Nagasaki in order to stop the killing of, as he put it, “all those kids.”

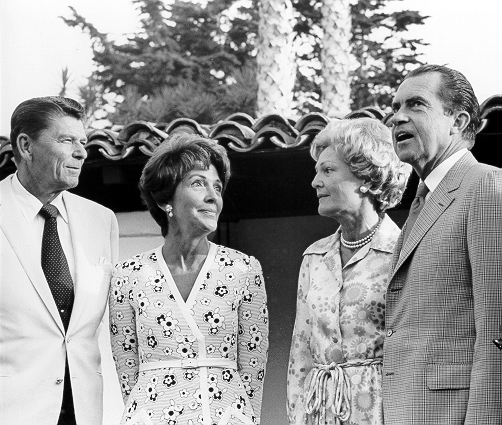

Image Credit: US President Richard Nixon and First Lady Pat Nixon meet with California Governor Ronald Reagan and his wife Nancy, July 1970 White House photo by Ollie Atkins. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: US President Richard Nixon and First Lady Pat Nixon meet with California Governor Ronald Reagan and his wife Nancy, July 1970 White House photo by Ollie Atkins. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.And now, in 2017, Trump has promised the complete destruction of North Korea. Will there be an about-face? As unlikely as that seems, it most certainly will not happen without an antinuclear movement. And antinuclear efforts do persist: This year’s Nobel Peace Prize went to the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons in recognition of the recent UN treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons. But we have not yet seen the wide coalition that confronted nuclear weapons throughout the Cold War, from Abolition 2000 and American Peace Test, to the War Resister’s League and Women’s Action for Nuclear Disarmament. And yet, so many Americans have already mobilized against Trump, including women and scientists, groups that have in the past opposed nuclear weapons as part of their agenda. Why not once again?

For all rhetoric, Trump’s nuclear weapons policy is, so far, in line with previous presidents. His reputation suggests Americans can do nothing but cross their fingers and prepare to duck and cover. But in the past, the American people have demanded cautious nuclear policies. Will Trump listen to public opinion? Will he recognize the stigma of nuclear weapons? If such a goal appears futile, it bears remembering that nuclear war has seemed all but certain in the past as well. And instead of succumbing to despair, apathy, or paralysis, millions of Americans chose inspiration and action instead.

Featured image credit: Nuclear Weapons Test by WikiImages. Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post Resisting doomsday: The American antinuclear movement appeared first on OUPblog.

The Quotable Guide to Punctuation Quiz Part Two

Quotations can be humorous and informative when drawn from the words of notable figures, from Shakespeare, Mark Twain, and Jerry Seinfeld to Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, Jennifer Lawrence, and many others. But can you spot which quote is punctuated correctly? Do you consider yourself a punctuation expert? Test your knowledge with this quiz.

For more explanations, guidelines, rules, and advice, see Stephen Spector’s The Quotable Guide to Punctuation.

Featured image: “Cursive” by A. Birkan ÇAGHAN. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The Quotable Guide to Punctuation Quiz Part Two appeared first on OUPblog.

April 9, 2018

Being Church as Christian hardcore punk

What is church? In the social sciences, church is ordinarily conceptualized as a physical gathering place where religious people go for worship and fellowship. Church is sacred; it is not secular. With this idea of church in mind, sociologists find that U.S. Christian youth (particularly young white men) are dropping out of church. Some are dropping out because they have lost faith in God. Others, however, are leaving church because they feel alienated from organized religion, not because they stopped being Christians. This rise in “unchurched believers” raises a question: how are Christian youth creating and expressing church beyond the confines of a religious institution?

In an effort to understand how Christians are doing church outside of established church walls, I turn to music. Protestant evangelical Christians believe that music is a powerful resource for making congregants feel God in the presence of others and for actualizing spiritual membership across difference. Yet despite the important role music plays in evangelical congregations and communities, few studies consider music as church. The studies that do, primarily examine the function of music in spaces that are explicitly religious, such as worship concerts or Christian rock festivals. What gets missed is how young people are enacting church through music in settings that are also secular.

I study how some evangelical youth are enacting church in an antagonistic music scene that takes a stand against religion and religious authority. My case: U.S. Christian Hardcore, a heavy metal-influenced form of punk rock comprised of Christian bands, show promoters, and subcultural ministry teams who mesh evangelical beliefs about sin and salvation with a music culture that values social nonconformity. In step with the hardcore idea that religious people are hypocrites, Hardcore Christians criticize the “mainstream church” for being insincere about the evangelical mission to reach out and bring society’s outcasts to Christ (i.e. other young white men involved in hardcore and metalcore music).

Church is not a place to go; church is a state of being that Christians can collectively express and mobilize in a range of social settings.

In an effort distance themselves from this religious mainstream, Hardcore Christians modify the popular phrase “spiritual but not religious,” calling themselves “Christian but not religious.” As one interviewee explained it, they are Christian but not religious because, “We follow Christ but we don’t act like Sunday Christians.” By not acting like Sunday Christians, these youths become, as the chart-topping Christian metalcore band For Today puts it, “Fearless” in their faith.

Christian Hardcore offers unique insights into how youths are using music to collectively reimagine church against mainstream Christian congregations and in spaces and practices that are also secular. Christian Hardcore youth are being church in ways that purposefully bring religious and nonreligious communities together. The Christian Hardcore act of being church takes shape in and through playing and moshing to hardcore music, making a Christian presence at hardcore shows, and getting to know non-Christians through music and tattoos. Through their music and at live shows, these youth underscore evangelical beliefs about personal salvation and evangelical witness to propose a new way to think about church: church is not a place to go; church is a state of being that Christians can collectively express and mobilize in a range of social settings.

By making these kinds of claims, Hardcore Christians accomplish what Gerardo Marti terms “religious institutional entrepreneurialism”—they work within the field of subcultural Christian ministries to carve out and legitimize a new understanding of church that is not confined to explicitly religious spaces. If music is church in religious institutions than music can also be church in social settings that are also secular.

Featured image credit: Photo by picjumbo. CC0 via Pexels.

The post Being Church as Christian hardcore punk appeared first on OUPblog.

April 8, 2018

Musician or entrepreneur? My journey began with popcorn

“Entrepreneurship.” It’s such a troublesome word, partly because it’s been overused and misapplied such that it’s become a buzz-word—which is never conducive to clarity of meaning or purpose. But it’s also a difficult word to get our hands around because it has many different meanings and can play out in so many ways. So what is it about entrepreneurship that I feel is so important for us in classical music to embrace?

I can remember quite clearly the moment when I began the path towards entrepreneurship: that moment when you realize you have to change the way you’ve been thinking about things and the way you’ve been approaching a problem. For me, that moment occurred when I was working at a concession stand at The University of Texas events center, scooping popcorn for patrons who hardly noticed me, much less cared about who I was or what my circumstances were. I was a food dispenser, and that was all.

The year was 2001, two months after 9/11. I was seven years out of my DMA in composition from Rice University, had already had my Concerto for Clarinet and Orchestra recorded by Richard Stoltzman and the Seattle Symphony, and had a chamber orchestra piece performed at Lincoln Center. I had been sure those milestones would soon open more doors, and I was confident my career was about to take off; it was only a matter of time before my name was gracing concert programs from coast to coast.

And then I hit a wall. The commissions dried up, the performances slowed to a trickle. I began to feel like I was losing my creative voice. A crisis ensued, one that was as much personal as it was professional. I didn’t realize at the time that what while I was a musician, I was not yet an entrepreneur.

By the time I had finished my degree program at Rice, I had decided that an academic career was not for me. My teachers were appalled: after all, what does one do with a doctorate in music composition if not become a college professor? But I was adamant that I was going to make my living as a working musician—composing and performing were to be my sole activities, undiluted by teaching or any other institutional distractions.

My mentor at Rice, Paul Cooper, was dubious. The day I came to his office to announce my decision felt momentous to me, as if I were announcing a break-up or sharing a dread diagnosis. I delivered my speech, well-rehearsed, and then the room was quiet for some time while he sat there in his leather chair, puffing away on his cigarette, his eyes reflecting deep thought. Finally, exhaling a cloud of smoke, he looked up at me and quietly said, “Well, Jeff, if anyone can do it you can.”

So what’s the missing piece? What we need is entrepreneurship.

So I jumped off the cliff—and seven years later here I was, scooping popcorn for basketball fans attending a game I couldn’t even watch.

And in that moment, I knew: something had to change. I could no longer tell myself that if I just continued to persevere that things would somehow turn around.

This story is hardly unique; I’m sure many readers will be able to relate to their own version of it. Sometimes it feels like we were set up: our education trained us to be the finest musicians we could be, but nothing else. Perhaps we were stars at our respective institutions, hailed by our teachers as one of the special talents who were destined for a prominent career, and this gave us a false sense of how easy it would be to win over the wider world. But once that initial post-graduation boost was spent, a cold reality hit: we had no idea what to do next. Faced with no other alternative, we take a day-job that eats up our time and saps our energy, making the whole enterprise of building a music career even more challenging. Many of us end up leaving music altogether.

Sound familiar? If so, you’re not alone.

So what’s the missing piece? What we need is entrepreneurship.

For starters, entrepreneurship is not, fundamentally, about making money. It’s based on the principle that the value of something resides in its benefit to someone else. If we want to unlock value for our work, we have to first understand the needs and sensibilities of our would-be customer (or our hoped-for audience) and then create a way to meet those needs through what we have to offer. Entrepreneurship is about enabling art’s deepest, most valuable purpose: connecting with people, creating community, challenging us to view the world from new and different perspectives, and stirring the soul. It’s about empowering artists with the tools they need to release the value of their work by connecting it with a market that desires it. And when it’s done well, entrepreneurial action exists harmoniously within the artist’s creative life, each side fueling creative insights for the other.

In the end, selling popcorn helped me through a rough patch in my life. But it was not an activity I wanted to keep as part of my career portfolio. Yet it shows just how entrenched we are when it comes to our career options and what it takes to develop them I had to find myself in the middle of every musician’s worst nightmare—doing something menial and completely divorced from one’s training and passion, just to survive—before I began to look at my artistic life through a new lens. Once I began to explore entrepreneurship, I discovered not only a more diverse palette of potential careers, I discovered that it could open up new creative possibilities as well.

Featured image credit: “Popcorn” by jayneandd. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr .

The post Musician or entrepreneur? My journey began with popcorn appeared first on OUPblog.

The art of microbiology

Sir Alexander Fleming famously wrote that “one sometimes finds what one is not looking for”. The story of Fleming’s serendipitous discovery of penicillin in the 1920s is familiar to most microbiologists. While the Scottish scientist and his family were on vacation, a fungal contaminant spread across – and subsequently killed – a lawn of bacteria growing on agar plates from one of his experiments. Fleming’s meticulous bookkeeping and astute observations of this chance event paved the way for the scientific exploration of antibiotics and revolutionized microbiology, having monumental effects on human health and longevity. Fleming seemed to be in the right place at the right time doing the right thing – but was the discovery a simple matter of good luck? What piqued Fleming’s curiosity toward this unexpected mould that most microbiologists would have overlooked as a commonplace laboratory annoyance?

Scholars believe his inquisitiveness was stimulated by his artistry: he was a self-taught watercolor painter.

Throughout his scientific career, Fleming entertained himself by fusing his painter’s techniques and his microbiology skills in the creation of agar art. In his lab, instead of using watercolors on canvas, he would paint with colored microbes on Petri dishes. The microbes would grow from a dilute invisible ink to vibrant pigment-expressing biofilms after a few days, creating living microbial masterpieces. His creativeness and visual acuity is thought to have driven his investigation of contamination he might have otherwise thrown out. Fleming later used a more controlled microbial painting technique – cross-streaking experiments (Figure 1) – to verify the lethality of penicillin against a variety of disease-causing bacteria. Subsequent researchers have used this same technique to search for other microbe-produced antibiotics (e.g. Selman Waksman’s discovery of streptomycin).

Figure 1. Copy of Fleming’s streak palette depicting a variety of bacterial pathogens “painted” onto agar next to a strip of penicillin, by Sarah Adkins. Used with permission.

Figure 1. Copy of Fleming’s streak palette depicting a variety of bacterial pathogens “painted” onto agar next to a strip of penicillin, by Sarah Adkins. Used with permission.For centuries, the intersection of science and art has fueled discoveries like Fleming’s and inspired some of the most far-reaching paradigm shifts in science and education. Since ancient times, the disciplines’ synergistic influence on each other has inspired scientific and technological progress as well as innovation in the arts. From Galileo (musician and astronomer) to John James Audubon (painter and ornithologist) to Niels Bohr (physicist and abstract art lover) and many others, we see the interplay of objective reason and aesthetic expression advancing both science and art.

Figure 2. Left, Neurons by Maria Peñil Cobo and Mehmet Berkmen, First place 2015. Right, Dancing Microbes by Ana Tsitsishvili, Third Place 2017. Used with permission.

Figure 2. Left, Neurons by Maria Peñil Cobo and Mehmet Berkmen, First place 2015. Right, Dancing Microbes by Ana Tsitsishvili, Third Place 2017. Used with permission.Which brings us to our current topic: the growing popularity of Sir Fleming’s pastime, agar art. Ever since the inception of the American Society for Microbiology’s annual Agar Art Contest in 2015, the scientific art contest has captivated both the attention of the general public and scientists from across the globe, with winning entrants from Hartford, Connecticut to Tbilisi, Georgia (Figure 2).

This international contest, reading about Fleming’s discovery, and the chance encounter of a newly-minted microbiology professor and a student double-majoring in studio art and biology at UAB, were some of the influencing factors in our decision to reform our Biology of Microorganisms class as a Course-based Undergraduate Research Experience (CURE) based around agar art (Figure 3). This curriculum uses students’ unique agar art, made with fresh soil isolates, to help students intuitively explore questions in microbial ecology. Like Fleming and agar artists across the globe, our students create their own microbial masterpieces from soil microbes. But this exercise isn’t just a fun, gimmicky activity – microbes, unlike paint, are subject to ecological pressures like antibiotic production and resistance, meaning that the intended painting is quite different from what students actually look at after a few days of growth. These varying plates prompt student questions: why are the plates different, and how are the microbes interacting with each other? Subsequently, students design and execute experiments on their microbes to scientifically explore these ecological questions, sometimes discovering novel results that may be of interest to the scientific community at large. The integration of art and science in the course works to give students more freedom and control in their education, as well as a sense of what it’s like to be part of genuine scientific discovery. These are key concepts in CURE courses, which have been shown to have a number of positive effects on student outcomes relative to traditional “cookbook” lab classes.

A UAB student and her agar art. As part of her introductory microbiology course, this student isolated two colorful soil microbes and used them to trace a “mandala” she designed. Image from Adkins, Rock, and Morris 2018. Used with permission.

A UAB student and her agar art. As part of her introductory microbiology course, this student isolated two colorful soil microbes and used them to trace a “mandala” she designed. Image from Adkins, Rock, and Morris 2018. Used with permission.It’s not all painting and playing in the dirt: compared to students from a standard cookbook lab, our students were more likely to give positive answers on a test of attitudes associated with pursuing STEM careers. “I’ve had to learn how to make my own process and my own methods and figure it out. That makes me feel more comfortable with being a scientist,” one of our students commented. Allowing students autonomy and creativity in how they pursue learning has been shown to not only increase mastery of material and ease in relating to scientists, but also retention in STEM programs. Integrating art and aesthetics into scientific inquiry, either on the lab bench or in the classroom, might help foster a new generation of creative scientists. After all, discoveries often happen when you find what you were not looking for.

Featured image credit: Beach scene with bacterial strains expressing different kinds of fluorescent protein, from the laboratory of the Nobel prize-winning biochemist Roger Tsien. Image by Nathan Shaner. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The art of microbiology appeared first on OUPblog.

The astronomer Johannes Stöffler and the reform of Easter

This year marks the fifth centenary of the publication of the Calendarium Romanum magnum, a carefully crafted ensemble of astronomical tables and detailed supplementary treatises that qualifies as one of the most impressive manifestations of the mathematical culture of the Northern Renaissance. Its author, the Swabian astronomer Johannes Stöffler (1452–1531), had spent several decades of his career as a parish priest before being appointed to the University of Tübingen’s newly established chair of mathematics in 1507. Besides teaching maths and astrology to illustrious sixteenth-century figures such as Philip Melanchthon, Johannes Schöner, and Sebastian Münster, Stöffler’s contemporary fame rested chiefly on his astrological prognostications and skills as an instrument maker, but also on the great success of his Almanach nova, first published in 1499 in collaboration with Jacob Pflaum, which recorded the daily positions of the planets for a period of 33 years.

Stöffler’s abilities as an astronomical calculator come to the fore very clearly in the 290-page Calendarium Romanum magnum (1518), which he dedicated to the astrology-enthused ruler of the Holy Roman Empire, Maximilian I. The scope of the Calendarium’s tables was more circumscribed than one’s average set of ephemerides, however, being restricted for the most part to the positions and syzygies (i.e. conjunctions and oppositions) of the Sun and Moon. Its introductory chapters demonstrated in great detail how the information contained in these tables could be harnessed for various purposes: keeping time, administering medical remedies, predicting eclipses, and, most important of all, calculating the dates of the mobile feast days.

Johannes Stöffler (1452–1531). Engraving by Theodor de Bry, published in Jean-Jacques Boissard, Icones virorum illustrium, pars II (Frankfurt/Main, 1598), p. 274. Source: Museum im Melanchthonhaus Bretten (Creative Commons license 3.0)

Johannes Stöffler (1452–1531). Engraving by Theodor de Bry, published in Jean-Jacques Boissard, Icones virorum illustrium, pars II (Frankfurt/Main, 1598), p. 274. Source: Museum im Melanchthonhaus Bretten (Creative Commons license 3.0)Stöffler was well aware that the latter topic had been the cause of ongoing controversy within the Roman Church. Only a few years prior to the publication of his Calendarium, the Fifth Lateran Council (1512–1517) had been busy making preparations for a reform of the dating of Easter Sunday. This project came at the tail end of four centuries of increasingly vehement complaints about the calendrical cycles used by the Church, which were no longer in tune with the courses of the Sun and Moon. This failure caused frequent violations of the rules governing the date of Easter Sunday, which was defined as the first Sunday after the first full moon to fall on or after the vernal equinox. Eager to put an end to this perceived scandal, the Lateran Council and its presiding pope (Leo X) set up a commission charged with solving the problem. Part of its mission was to solicit advice from the outside, by sending letters to rulers, bishops, universities, and scholars from all over Europe. The list of experts who wrote back to Rome with their suggestions includes Nicholas Copernicus, whose annotated personal copy of the Calendarium Romanum magnum is still extant and has even been used to sample the astronomer’s DNA.

Another contributor to this project was Stöffler himself, who submitted his report on the calendar problem in 1515. This report is lost, but its contents can be reconstructed from the Calendarium. In it, Stöffler expresses the usual set of worries about the scandalous state of the ecclesiastical calendar, which he and many of his contemporaries feared was liable to undermine the authority of the Church and expose it to the ridicule of unbelievers. Where he deviated from the mainstream were his plans for how to solve the problem. Rather than attempting to improve the existing calendrical cycles with a slight bit of nip and tuck, Stöffler declared it best to leave the whole business of calculating Easter to astronomers, who could use their own tables and algorithms to predict the time of the vernal equinox and the true full moon. For this solution to work, the Church and its astronomers had to base all relevant calculations on a common meridian, as this was the only way to ensure that Christians on the newly discovered West Indies would celebrate the feast on the same date as those in India or the Holy Land. Stöffler recommended placing this reference meridian in the city of Rome, the centre of Latin Christianity.

Eclipse predictions in Johannes Stöffler, Calendarium Romanum magnum (Oppenheim, 1518), sig. D1v. Source: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Rar 8909 q (Public Domain Mark 1.0)

It is no secret that the Roman Church never went along with Stöffler’s proposal, but instead opted for a fully cyclical computation of Easter in the guise of the Gregorian calendar. Introduced in October 1582 under the auspices of Pope Gregory XIII, the Gregorian calendar has found numerous admirers, but about as many critics over the past 436 years of its run. Complaints have targeted its bewilderingly complicated structure — the Gregorian dates of Easter Sunday return in the same order only after 5.7 million years! — but also the compromises its inventors made with regard to astronomical accuracy. In some parts of the Christian world, in particular the Orthodox East, the Gregorian reform of Easter reckoning has never been adopted and proposals of the sort voiced by Stöffler five centuries ago still remain relevant to the contemporary discussion. The possibility of a new reform that would lead to an ecumenical date of Easter was raised as recently as June 2015 by Pope Francis, who declared his Church’s willingness to give up the Gregorian calculation for the sake of Christian unity. Non-Catholic supporters of this plan include the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, who in January 2016 expressed his preference for an Easter fixed to the second or third Sunday in April. His solution would no doubt be welcomed by businesses, school administrations, and other institutions with an interest in stabilizing holiday schedules. It would not have been acceptable to Johannes Stöffler, however, whose work emphasized the historical-theological underpinnings that tie Easter to its Jewish precursor, Passover, and hence to the phases of the Moon. It remains to be seen whether such objections will continue to hold sway in the twenty-first century.

Featured image credit: time calendar saturday weekend by Basti93. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post The astronomer Johannes Stöffler and the reform of Easter appeared first on OUPblog.

April 7, 2018

National Volunteer Month: a reading list

On 20 April 1974, President Richard M. Nixon declared National Volunteer Week, to honor those Americans whose unpaid “efforts most frequently touch the lives of the poor, the young, the aged and the sick, but in the process the lives of all men and women are made richer.” Since that time, this commemoration has been extended to a full month to recognize the nearly one-in-four Americans, numbering nearly 63 million, who offer their time, energy, and skills to their communities. Volunteer activities are far-ranging and encompass activities like tutoring school children, beautifying run-down neighborhoods and littered highways, planting community gardens, giving tours of historical sites, ringing up purchases at a hospital gift shop, delivering meals to homebound older adults, performing music for nursing home residents, or offering one’s professional, managerial, or organizational skills to non-profit organizations.

While it might appear that older adults are the recipients of volunteer labor, they actually play a large and vital role in the volunteer work force. A recent study by the Corporation for National Community and Service documented that more than 21 million adults aged 55 and older contributed more than 3 billion hours of volunteer service to their communities in 2015, with these contributions valued at $77 billion.

Each April, National Volunteer Month provides a time to celebrate the contributions of volunteers young and old, raise awareness of the personal and societal benefits of volunteering, increase public support for this vast and often invisible unpaid workforce, and educate potential volunteers about the opportunities available to them. In honor of the 21 million older adult volunteers, we have created a reading list of articles from Gerontological Society of America journals that reveal new scientific insights into the benefits of volunteering for older adults and the people and communities they help.

“Does Becoming a Volunteer Attenuate Loneliness among Recently Widowed Older Adults?” by Carr et al.

The authors explore whether becoming a volunteer protects against older widows’ and widowers’ loneliness. Using data from the 2006-2014 waves of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), they find that widowed persons have significantly higher levels of loneliness than their married counterparts, yet volunteering 2+ hours a week attenuates loneliness to the point where widowed volunteers fare just as well as their married counterparts. Volunteering less frequently does not buffer against the strains of widowhood, however. The loss of a spouse is so profound and daily life changes so dramatic that more intense levels of social engagement may be necessary to protect against older widowed persons’ feelings of loneliness.

“The Relation of Volunteering and Subsequent Changes in Physical Disability in Older Adults” by Carr, Kail and Rowe (2018).

This study examines whether becoming a volunteer is linked with functional limitations and whether these effects are conditional on whether one volunteered more or less than two hours per week. Using data from Health and Retirement Survey (HRS), they find that starting a new volunteer role slows the progression of disability, at both high and low intensity volunteering levels for women, yet these benefits accrue for men only at the higher level of volunteering frequency. Low intensity volunteering may be less protective to men than women because men tend to be more physically active, such that adding an incremental set of volunteering tasks may not deliver substantial health benefits.

“Extracurricular Involvement in High School and Later-Life Participation in Voluntary Associations” by Greenfield and Moorman (2018).

Using more than 50 years of data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS), the authors examine whether the number of extracurricular activities one participated in during high school is linked with subsequent participation in voluntary associations like religious groups, unions, sports teams, or professional organizations. Participation in voluntary associations over the life course is consistently higher among those with greater extracurricular participation in high school. This study reveals clear patterns of continuity and change, where those who were “joiners” in high school continued this behavior throughout their lives although later-life transitions like retirement and the onset of physical health problems may discourage people from such engagement in later life.

“Longitudinal Associations between Formal Volunteering and Cognitive Functioning” by Proulx et al. (2018).

Using nine waves of data from the Health and Retirement Study, the authors find that formal volunteering is linked with higher levels of cognitive functioning over time, especially for working memory and processing. The positive impact of formal volunteering on memory weakened over time, yet the impact on working memory and processing intensified over time. The authors conclude that formal volunteering may enhance cognitive functioning by providing opportunities to learn or engage in new tasks, and to remain physically and socially active.

“Health Benefits Associated With Three Helping Behaviors: Evidence for Incident Cardiovascular Disease” by Burr et al. (2018)

Does volunteering affect specific disease outcomes? This study uses ten years of data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to explore the impact on cardiovascular disease (CVD) of three helping behaviors: formal volunteering, informal helping, and caregiving for a parent or spouse. Although caregiving was not linked to CVD risk, volunteering and providing informal help were linked with reduced risk of heart disease. Helping may enhance one’s health, especially if these prosocial behaviors are not particularly stressful or physically strenuous.

“Volunteering in the Community: Potential Benefits for Cognitive Aging” by Guiney et al. (2018).

This study reviewed 15 articles evaluating the association between volunteering and cognitive functioning. The authors found that volunteering has modest benefits for global cognitive functioning as well as some specific indicators such as attentional control, task switching, and both verbal and visual memory, with the magnitude of these associations varying based on whether the study used longitudinal versus cross-sectional data. They also delineated potential explanatory mechanisms, whereby volunteering promotes cognitive, social, and physical activity which provide neurological and mental health benefits that ultimately enhance cognitive functioning.

Featured image credit: “bonding” by rawpixel. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post National Volunteer Month: a reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers