Oxford University Press's Blog, page 264

April 7, 2018

National Volunteer Month: a reading list

On 20 April 1974, President Richard M. Nixon declared National Volunteer Week, to honor those Americans whose unpaid “efforts most frequently touch the lives of the poor, the young, the aged and the sick, but in the process the lives of all men and women are made richer.” Since that time, this commemoration has been extended to a full month to recognize the nearly one-in-four Americans, numbering nearly 63 million, who offer their time, energy, and skills to their communities. Volunteer activities are far-ranging and encompass activities like tutoring school children, beautifying run-down neighborhoods and littered highways, planting community gardens, giving tours of historical sites, ringing up purchases at a hospital gift shop, delivering meals to homebound older adults, performing music for nursing home residents, or offering one’s professional, managerial, or organizational skills to non-profit organizations.

While it might appear that older adults are the recipients of volunteer labor, they actually play a large and vital role in the volunteer work force. A recent study by the Corporation for National Community and Service documented that more than 21 million adults aged 55 and older contributed more than 3 billion hours of volunteer service to their communities in 2015, with these contributions valued at $77 billion.

Each April, National Volunteer Month provides a time to celebrate the contributions of volunteers young and old, raise awareness of the personal and societal benefits of volunteering, increase public support for this vast and often invisible unpaid workforce, and educate potential volunteers about the opportunities available to them. In honor of the 21 million older adult volunteers, we have created a reading list of articles from Gerontological Society of America journals that reveal new scientific insights into the benefits of volunteering for older adults and the people and communities they help.

“Does Becoming a Volunteer Attenuate Loneliness among Recently Widowed Older Adults?” by Carr et al.

The authors explore whether becoming a volunteer protects against older widows’ and widowers’ loneliness. Using data from the 2006-2014 waves of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), they find that widowed persons have significantly higher levels of loneliness than their married counterparts, yet volunteering 2+ hours a week attenuates loneliness to the point where widowed volunteers fare just as well as their married counterparts. Volunteering less frequently does not buffer against the strains of widowhood, however. The loss of a spouse is so profound and daily life changes so dramatic that more intense levels of social engagement may be necessary to protect against older widowed persons’ feelings of loneliness.

“The Relation of Volunteering and Subsequent Changes in Physical Disability in Older Adults” by Carr, Kail and Rowe (2018).

This study examines whether becoming a volunteer is linked with functional limitations and whether these effects are conditional on whether one volunteered more or less than two hours per week. Using data from Health and Retirement Survey (HRS), they find that starting a new volunteer role slows the progression of disability, at both high and low intensity volunteering levels for women, yet these benefits accrue for men only at the higher level of volunteering frequency. Low intensity volunteering may be less protective to men than women because men tend to be more physically active, such that adding an incremental set of volunteering tasks may not deliver substantial health benefits.

“Extracurricular Involvement in High School and Later-Life Participation in Voluntary Associations” by Greenfield and Moorman (2018).

Using more than 50 years of data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS), the authors examine whether the number of extracurricular activities one participated in during high school is linked with subsequent participation in voluntary associations like religious groups, unions, sports teams, or professional organizations. Participation in voluntary associations over the life course is consistently higher among those with greater extracurricular participation in high school. This study reveals clear patterns of continuity and change, where those who were “joiners” in high school continued this behavior throughout their lives although later-life transitions like retirement and the onset of physical health problems may discourage people from such engagement in later life.

“Longitudinal Associations between Formal Volunteering and Cognitive Functioning” by Proulx et al. (2018).

Using nine waves of data from the Health and Retirement Study, the authors find that formal volunteering is linked with higher levels of cognitive functioning over time, especially for working memory and processing. The positive impact of formal volunteering on memory weakened over time, yet the impact on working memory and processing intensified over time. The authors conclude that formal volunteering may enhance cognitive functioning by providing opportunities to learn or engage in new tasks, and to remain physically and socially active.

“Health Benefits Associated With Three Helping Behaviors: Evidence for Incident Cardiovascular Disease” by Burr et al. (2018)

Does volunteering affect specific disease outcomes? This study uses ten years of data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to explore the impact on cardiovascular disease (CVD) of three helping behaviors: formal volunteering, informal helping, and caregiving for a parent or spouse. Although caregiving was not linked to CVD risk, volunteering and providing informal help were linked with reduced risk of heart disease. Helping may enhance one’s health, especially if these prosocial behaviors are not particularly stressful or physically strenuous.

“Volunteering in the Community: Potential Benefits for Cognitive Aging” by Guiney et al. (2018).

This study reviewed 15 articles evaluating the association between volunteering and cognitive functioning. The authors found that volunteering has modest benefits for global cognitive functioning as well as some specific indicators such as attentional control, task switching, and both verbal and visual memory, with the magnitude of these associations varying based on whether the study used longitudinal versus cross-sectional data. They also delineated potential explanatory mechanisms, whereby volunteering promotes cognitive, social, and physical activity which provide neurological and mental health benefits that ultimately enhance cognitive functioning.

Featured image credit: “bonding” by rawpixel. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post National Volunteer Month: a reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

American Renaissance: the Light & the Dark

The American Renaissance—perhaps the richest literary period in American history, critics argue—produced lettered giants Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Emily Dickinson. Much like the social and historical setting in which it was birthed, this period was full of paradoxes that were uniquely American. Literary historians traditionally distinguish between the light authors (Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman) and the dark ones (Poe, Hawthorne, and Melville). Dickinson, like daybreak, ionically bonds both the dark and the light.

The optimistic ones delved into themes of nature’s beauty, spiritual truths, the primacy of poetic imagination, and the potential divinity of each individual. The gloomier set, however, explored paradoxes, haunted minds, perverse or criminal impulses, and ambiguity.

Using the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature we rounded up the prominent figures and the themes they popularized during this period:

The Light

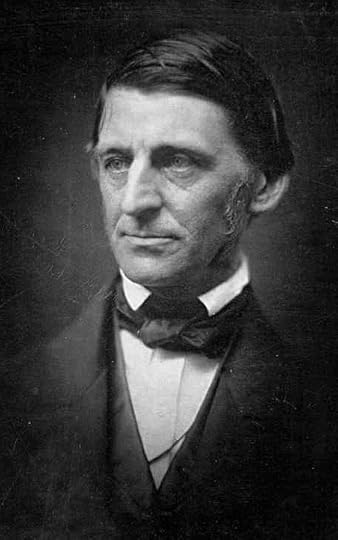

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803 – April 27, 1882): Historians customarily say that the American Renaissance started with the New England philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson. He set out to forge a literary that was distinctively American: fresh, vigorous, adventurous. He admired the brash individualism he saw in frontier legends Daniel Boone and David Crockett. In his literature he pushed for concepts like self-reliance, nonconformity, the primacy of the imagination, an appreciation of nature for both physical beauty and spiritual resonance. These ideas spread to the intellectual life in Massachusetts and elsewhere.

Image credit: Ralph Waldo Emerson by User:Scewing. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Ralph Waldo Emerson by User:Scewing. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817 – May 6, 1862): In his senior year at Harvard, fellow Massachusetts native Henry David Thoreau read Emerson’s Nature and was inspired. Key Emersonian concepts can be found in the central themes of Thoreau’s Walden. It is a testament to Thoreau’s impact on political and philosophical ideas that while in jail Mohandas Ghandi read Civil Disobedience. Through the mid-twentieth century, Thoreau’s reputation as a critically important writer and thinker on many fronts continued to grow.

Walt Whitman (May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892): After discovering Emerson’s work in the 1850s, Walt Whitman wrote, “I was simmering, simmering, simmering; Emerson brought me to a boil.” The New Englander philosopher’s influence can be seen in Whitman’s Leaves of Grass: his flowing, prose-line poems threading Emerson’s idea about organic styles that followed the rhythms of nature. Though the Poet of Democracy—as he is also called—is a central and influential poet in the American canon, he was still stubbornly ignored by the literary establishment of his time. The objections, which lasted until the 1940s, were that his style was written in slang and obscene in content because of its references to sex and parts of the body. Now, his fame as America’s seminal poet is secure.

The Dark

Edgar Allan Poe (January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849): When Edgar Allan Poe died, some critics predicted that his works would be forgotten. Writers such as Conan Arthur Doyle, Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, and Stephen King answered them with a resounding “Never.” In stark contrast to the optimistic writers of the American Renaissance, Poe wrote tales that teemed with bizarre or macabre images: murder, necrophilia, live burial. He did not approve of senseless gore or sensationalism, which he found cheapened many of the literature that was common in the “Penny papers.” His attention to psychology, logic, and methodology influenced generations of sci-fi and detective novelists.

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864): Sometimes called a ‘dark romantic,’ no other major American author of this period expressed greater doubts about the fundamental premises of the Light group than Nathaniel Hawthorne. He was confounded by and explored the contrasting strain in American culture, associated with darkness, violence, and piety. The Scarlett Letter grappled with America’s seamy, Puritanical past. Hawthorne followed popular sensational novelists who used subversive characters to attack pious contradictions. However, Hawthorne bestowed these stereotypical characters with new resonance and depth. By incorporating these 19th-century characters into Puritan era, his masterpiece exudes irony, symbolism, and psychological complexity.

Image credit: Daguerrotype of Emily Dickinson, c. early 1847. It is presently located in Amherst College Archives & Special Collections. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Daguerrotype of Emily Dickinson, c. early 1847. It is presently located in Amherst College Archives & Special Collections. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Herman Melville (August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891): Paradoxes are at the heart of America: how does a country built upon the principles of liberty and freedom practice slavery? Herman Melville compresses paradox into his body of work. In the towering novel Moby-Dick; or, The Whale, Melville mixes an array of uniquely rich and paradoxical characters: the irreverent yet likable Ishmael; the savage but humane cannibal Queequeg; and Captain Ahab, who is described paradoxically as “a grand, ungodly, god-like man,” on a mad yet justified vengeful quest.

Daybreak

Emily Dickinson (December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886): The shy, home-centered Emily Dickinson was fascinated with the sensational newspapers of the time. The war years (1861-1865) opened up complex and existential questions for Dickinson, which led to her most prolific period: of her nearly 1,800 poems, approximately half were written during those years. Skepticism and musings on death and the afterlife permeated her work. Yet, she refused to tie herself solely to melancholy. In many ways, themes that the previous writers explored culminated in her poetry. Her skepticism, discussion of mental illness, and unmasking of false appearances evoke the works of Poe, Hawthorne, and Melville. There were moments that matched the brightest passages in Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman. There is one area, however, in which Dickinson stands apart from the others: her unusually flexible treatment of womanhood. Dickinson could satirize female gentility or the cult of domesticity and elsewhere play the strong woman defending her “Master” or the devoted lover.

Featured image: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post American Renaissance: the Light & the Dark appeared first on OUPblog.

April 6, 2018

The strange case of Colonel Cyril Wilson and the Jihadists

The aftermath of the Arab Revolt of 1916-18 and the settlement in the Middle East after the First World War still resonates, world-wide, after a century. It is not only the jihadists of the so-called Islamic State and other groups who rail against the Sykes-Picot Agreement—the secret arrangement between Britain, France, and Russia that carved up much of the territory of the Ottoman Empire. Many moderate Muslims have a rankling feeling of betrayal, being aware that Sykes-Picot contradicted the British promise—albeit a vague one—of a large independent territory for Sherif Hussein of Mecca, the leader of the Arab Revolt, if he would rise up against the Ottomans, Britain’s wartime enemies.

Yet jihadists are not a new phenomenon. On 14 November 1914, encouraged by German intelligence, the Ottoman sultan and caliph declared jihad, or holy war, against the Allies. The British were anxious about the threat: there were about seventy million Muslims in British India, a fifth of its entire population, and anti-British plotters had been active amongst them for many years. The British nightmare was that this small minority could be swelled by a huge number of newly fired-up Muslim jihadists. They were also concerned at the prospect of a rebellion by the Muslims of Egypt, a British protectorate: this could threaten the Suez Canal, Britain’s vital life-line to India. The British clung to the hope that given their support for Sherif Hussein, a direct descendant of the prophet Mohammed, their own Muslim citizens in India and elsewhere would find it difficult to rise up against them.

As if these threats were not enough, the British had another headache. In Jeddah (captured from the Ottomans in the early stages of the revolt) their representative, Colonel Cyril Wilson, knew that pan-Islamic jihadist agitators were amongst the hundreds of British Indian Muslims who lived in the town and also in Mecca. These men were organised in underground societies, and were scheming against Hussein for daring to throw in his lot with the infidels. They resented Hussein’s rebellion because they saw the Ottoman sultan and caliph as the bedrock and heart of their religion.

“Arrival of the Holy Carpet at Jeddah during the Muslim Hajj or pilgrimage.” Used with permission of Anthea Gray.

“Arrival of the Holy Carpet at Jeddah during the Muslim Hajj or pilgrimage.” Used with permission of Anthea Gray.The threat came to a head in autumn 1916. Wilson had a vital diplomatic and intelligence role, but his official job title was “Pilgrimage Officer,” a fiction to allay Arab sensitivity to British soldiers based near the Holy Places of Mecca and Medina. Wilson was supposed to be solely in charge of the smooth passage of the two thousand or so British Muslim pilgrims, who came mainly from India, after they disembarked at Jeddah and went on the yearly Hajj to Mecca. Jihadists amongst them, as well as those already in Jeddah and Mecca, wanted to obstruct the pilgrimage, discredit the British in Arabia, and spread anti-British subversion back in India. The stakes were high because Wilson knew that if the pilgrimage were to be disrupted, it would hand a propaganda coup to the Turks and to the jihadists, who would shout from the rooftops that the British could never be trusted with the pilgrimage and were not true friends of Muslims. Sherif Hussein would have lost face and the blow to the revolt could have been terminal.

Cyril Wilson brought in a top Indian Army intelligence officer, Captain Norman Bray, aided by the Persian spy Hussein Ruhi, who discovered that some powerful Arab plotters apparently intended to seize Sherif Hussein and hand him over to the Ottomans. Intrigue was endemic within the Hejaz, Hussein’s territory in what later became the eastern part of Saudi Arabia. In addition the leading jihadist, Mahmud Hassan, who lived in Mecca, planned to return to India after his campaign of subversion and disinformation in the Hejaz. In India he intended to vilify and discredit Hussein in the eyes of Muslims, and try to encourage mutiny among the men of the Indian Army. Bray and Ruhi gathered intelligence from their agents, outmaneuvered Mahmud and had him arrested and deported to a prison camp in Malta. Their secret work neutralised a serious threat to the revolt.

Where the wider threat from jihadism was concerned, it seems, with hindsight, that the Ottomans and Germany over-rated the power of pan-Islam, just as Britain over-rated the appeal of Arab nationalism to gain the support of Ottoman Arabs for Hussein’s revolt. Yet even though the British nightmare about revolution in their jewel in the crown, India, was perhaps overstated at times, it had a dark and powerful hold over their psyche.

The often forgotten diplomatic and intelligence efforts of Cyril Wilson and his small band of comrades kept the Arab Revolt on track, both during the pilgrimage and on a number of later occasions too, when a wavering Hussein threatened to throw in the towel. But perhaps inevitably, the success of the revolt was hollow, and Hussein’s territorial ambitions were dashed. He had visions of becoming caliph of a huge area, but the sophisticated town-dwellers of Syria and Mesopotamia would never have accepted that, and neither would Hussein’s great rival in central Arabia, Ibn Saud. Ultimately, what really counted were British and French imperial interests: they overrode everything else, as they would always do. The legacy of the revolt lives on in the increasingly tangled affairs of the Middle East and beyond.

Featured image credit: Bedouin fighters at the port of Wejh. Used with permission of Anthea Gray.

The post The strange case of Colonel Cyril Wilson and the Jihadists appeared first on OUPblog.

The four principles of medicine as a human experience

The standard in medicine has historically favoured an illness- and doctor-centered approach. Today, however, we’re seeing a shift from this methodology towards patient-centered care for several reasons. In the edited excerpt below, taken from Patient-Centered Medicine, David H. Rosen and Uyen Hoang explore four core principles that underlie the foundation of this clinical approach.

Acceptance

Acceptance is a trait that we believe is fundamental to all truly effective patient care. It is important to be clear what we mean by this simple word. Certainly acceptance has many commonplace meanings: acceptance of responsibility, obligation, assignments, and tasks. Of course, we mean all of these, but we also mean something much more specific. In its most fundamental sense, acceptance means the doctor takes the patient—the person as he is—into her mind, her heart, and her conscience. It is not an action, but an encompassing attitude. Furthermore, this attitude is not “mystical.” Rather, it is embedded in what is most basic to the human being. The doctor who fails to perceive this will never understand the essence of patient care and healing.

Why is this concept important? What does it have to do with modern medicine? The answer, we believe, lies in its intrinsic emphasis on receptivity rather than on action. Progressively, medicine has grown more action oriented, yet acceptance reminds us that, at the deepest level, humans need to be received, embraced, taken in, incorporated—all far more quiet and receptive modes of relatedness than those to which we are usually accustomed.

Empathy

The importance of empathy has been widely stressed along with its dimensions, described by many writers concerned with the doctor–patient relationship. It has been defined variously, with most of the definitions attempting to connote an emotional stance that avoids extremes of over identification on the one hand and excessive emotional detachment on the other. A useful definition describes empathy as the ability to understand and share in another’s feelings fully, coupled with the ability to know those feelings are not identical to one’s own.

Defining empathy may be difficult, but achieving it is even harder. Most students find that they tend to oscillate between periods of over identification with patients and periods of excessive detachment. The notion of striking a balance is obviously appealing but not simple to effect. In truth, accurate and consistent empathy with patients is an exacting skill—one that requires years of experience and effort to develop fully.

Empathy is one of the hardest skills to perfect. It is also one of our most effective tools. Nothing is fool proof, of course, but most situations that go awry do so from lack of empathy. Even enormously explosive situations can often be defused with accurate empathy. Obviously, the uses of empathy are not limited to understanding patients. One can also use empathy better to understand the complex and sometimes painful interactions that occur among various hospital personnel, including ourselves.

Doctor, patient, hospital by skeeze. CC0 public Domain via Pixabay.

Doctor, patient, hospital by skeeze. CC0 public Domain via Pixabay.Conceptualization

The conceptual basis for patient-centred medicine is derived from George Engel’s biopsychosocial model. Essentially, Engel’s thesis holds that no change can occur within one component of a system without eventually making an impact on other components of that system. Further, each system (e.g., a molecule, a human being, a family) holds a lower or higher place in relation to other systems in a hierarchy of systems. Approaching patient care from this perspective requires a shift in thinking away from a simplistic disease orientation toward the more complex and more effective stance that we describe here as patient-centred medicine. To be a good doctor, a truly complete one, physicians must understand molecules and cells, organelles and organs, but they must also understand the complex, ineffable miracle we call “the person.” Even this will not suffice, however; people relate primarily in twos but live in still larger systems—families, communities, and the biosphere itself.

Once upon a time, being a doctor must have seemed easier. Now it is more challenging than ever before. The onslaught of new information at all levels of the systems hierarchy has accelerated at an astonishing rate. These are not trivial advances, but major new trends, fundamental and far-reaching discoveries doctors must integrate and understand.

Competence

Ultimately, knowledge and intellect alone are not sufficient to make one a good doctor, but neither are compassion and empathy alone. We are dealing with live patients, real people who place themselves in our hands. What we do or do not do can make the difference between life and death, recovery and degeneration, health and illness. Even if we do not cause disability or death to a patient through gross incompetence, ultimately it is our competence that determines the quality of our patients’ lives on countless levels.

We cannot possibly be all things for all patients. We cannot even be all things for one patient. Yet competence does demand that we do many things. Above all, competence requires one to see the big picture. Finally, when doctors reach a patient they do something special. Perhaps it is just a touch or a look of understanding. One less tiny cut in the patient’s life. A small wound that heals instead of festering. That is competence.

Featured image credit: ‘lone star’ by Amy Humphries. Public Doman via Unsplash.

The post The four principles of medicine as a human experience appeared first on OUPblog.

April 5, 2018

The return of opiophobia

Opiophobia (literally, a fear of opioids or their side effects, especially respiratory suppression) has been around for a long time. Nowadays it’s primarily prompted by the opioid epidemic that has caused a five-fold increase in overdose deaths over the past two decades. With opioids implicated in over 40,000 deaths in the United States each year, interventions such as daily milligram limits, short-term prescribing, and “risk evaluation and mitigation strategies” are important public health measures.

In addition to responding to the epidemic, we also need to identify what caused it. One contributing factor was the short-sighted extrapolation of the well-documented benefits of opioids in end-of-life care to chronic, non-malignant conditions. Opioids represent an invaluable (and largely irreplaceable) treatment for extreme pain at the end of life, whereas long-term prescribing can often lead to addiction, diversion, and long-term side effects.

But just as it was wrong to assume that opioids would benefit chronically ill patients in the same fashion as dying patients, it is equally misguided to attribute the risks of opioids for non-malignant conditions to end-of-life situations. While limiting opioid prescribing for chronic conditions makes good sense, blanket restrictions on opioid prescribing could lead to inadequate treatment of pain and dyspnea at life’s end.

Even before the epidemic, opiophobia was a profound concern for physicians. Studies showed that concern for opioids causing a patient to stop breathing (especially at high doses) led many patients to endure significant pain at the end of life. In response, the Rule of Double Effect (RDE) was used to reassure physicians that judicious pain management at the end of life did not constitute euthanasia. Based on the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas, the RDE helps to determine whether an action that has two effects—one good and one bad—is morally permissible. The RDE has four basic components:

1. The act itself must be, at worst, morally neutral.

2. The bad effect cannot be the means to the good effect.

3. The good effect must outweigh the bad effect (principle of proportionality).

4. The agent must only intend the good effect, although the bad effect may be foreseen.

Opioids that are used to relieve severe pain (the good effect) but end up suppressing a patient’s respiratory drive (the bad effect) meet all four conditions:

1. Administering an FDA-approved medication for a condition it is indicated for is not morally bad.

2. Pain is relieved through direct action of the medication, not through the patient’s death.

3. In cases where the pain is severe and the patient’s prognosis is poor, the benefit of analgesia can outweigh the harm of hastened death.

4. In appropriately titrating the opioids, the physician’s intention is to treat pain, with the foreknowledge—though not the intention—that death might be hastened.

Image Credit: “Pills Prescription Bottle” by nosheep. CC0 via Pixabay.

Image Credit: “Pills Prescription Bottle” by nosheep. CC0 via Pixabay.While providing reassurance to some, the RDE has been criticized by others. Specific criticisms include its historical roots within a particular religious tradition, the complexity of physician intention, the responsibility for what occurs as a foreseeable result of someone’s actions (and not just what someone intended to happen), and the potential overemphasis on a physician’s intention (as opposed to the patient’s welfare).

While some have attempted to defend the RDE, others have questioned whether the RDE is really necessary to justify intensive opioid treatment at the end of life. The RDE, after all, is designed to justify actions that have two inevitable effects, one good and one bad. In the case of opioid treatment, however, respiratory suppression is far from inevitable. In point of fact, this side effect is actually rather rare when opioids are used appropriately.

In this respect, symptomatic treatment at the end of life is no different than nearly every other medical treatment, which involves a balancing of the hoped-for benefit with the possible complications or side effects. And while the bad effect in this case is indeed serious, death is also a risk of many other medical procedures. Far from necessarily hastening death, opioids often extend life in a patient who is dying. Opioids have been shown to prolong survival after ventilator withdrawal, likely by decreasing oxygen demand. Indeed, a large study of hospice patients found that opioid use was directly—rather than inversely—correlated with duration of life for terminally ill patients. Thus Fohr concludes: “In the case of medication to relieve pain in the dying patient, the RDE should be rejected not on ethical grounds, but for a lack of medical reality.”

Far from necessarily hastening death, opioids often extend life in a patient who is dying

Not only is the RDE unnecessary and often misapplied, appealing to it can actually be counterproductive as this risks perpetuating the misperception that opioids will certainly (or even likely) hasten death. Ironically, what was intended to empower physicians to optimally treat suffering—by assuaging concerns about euthanasia—could ultimately discourage them from achieving this goal by inextricably linking two effects: one noble, intended, and inevitable; the other frightening, unintended, and unlikely.

By attempting to reassure those who fear stepping over the line into euthanasia that they are not doing anything wrong, a great many others may be led to believe that hastened death is inevitable, rather than rare. Ethicists may bear some responsibility for this perception. A recent study of medical school ethics educators found that one-third believed that opioids were “likely to cause significant respiratory depression that could hasten death.” Understandably, these educators routinely appealed to the RDE as justification for such intensive pain management.

Given the uncertain—or even unlikely—correlation between opioid treatment at the end of life and hastened death, the RDE should not provide the sole justification of the former. Of course, some of the elements of the RDE would naturally factor into one’s analysis, such as whether the benefits of the treatment outweigh the risks. And to those with heightened concern about the ethicality of potentially hastened death, the RDE could provide valuable reassurance, especially given its roots in a religious tradition that might have prompted that very concern.

But for most physicians, all four components of the RDE need not necessarily be satisfied to justify a treatment with only potential complications. Otherwise, overreliance on the RDE could actually perpetuate the very injustice it was designed to prevent. As Angell notes, “I can’t think of any other area in medicine in which such an extravagant concern for side effects so drastically limits treatment.”

Featured Image Credit: “Focus on the hand of a patient in hospital ward” by Thaiview. Via Shutterstock .

The post The return of opiophobia appeared first on OUPblog.

What to do about tinnitus?

Tinnitus (i.e., ear or head noises not caused by external sounds) is common among the general population across the world. Tinnitus can be experienced as a “ringing in the ears.” It can also sound like a hissing, sizzling, or roaring noise. It can be rhythmic or pulsating. Tinnitus can be a non-stop, constant sound or an intermittent sound that disappears and returns without a pattern. It can occur in one or both ears.

Tinnitus may be caused by trauma to the head (e.g., blast exposure, such as bombs or other explosive devices, or injuries to the head. such as traumatic brain injuries). It also can be caused by acoustical trauma (e.g., loud noises from earsplitting concerts, listening to music too loud). While tinnitus is different than hearing loss, individuals may have to deal with both conditions.

Tinnitus is a symptom of neural damage and thus reflects that an injury occurred. As a “phantom sensation” or subjective symptom, it indicates neural damage. Currently, there is no cure for subjective tinnitus. Objective tinnitus differs than the more commonly experienced subjective tinnitus; objective tinnitus can be attributed to an internal sound source, such as a pulsating blood vessel that is adjacent to the auditory nerve. Thus, surgery may improve objective tinnitus, but not subjective tinnitus.

“Scientists may find a cure for subjective tinnitus someday.”

Scientists may find a cure for subjective tinnitus someday. Until a cure is found, extreme caution should be taken about internet promises about pills or techniques to cure tinnitus. We know from decades of research and clinical trials that there are some things that can help reduce suffering while having tinnitus. The following three steps can help you self-manage your tinnitus until a cure is found.

The first step that a person should take when experiencing tinnitus is to get a screening of the outer and inner ear and of one’s medical history by a physician or ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist to make sure there are no underlying medical issues that need to be treated (e.g., auditory lesions or vascular tumors).

A second step to take if you have tinnitus is undergo an audiological assessment. If you have a hearing impairment and tinnitus, using hearing aids can help in several ways. Hearings aids can amplify sounds from the environment, which help people pay less attention to the ‘internal noise’ created by tinnitus. Modern hearing aids also offer features of providing ‘white noise’ or other sounds that helps people pay less attention to their tinnitus. In general, it is helpful for people to add to their ‘sound environments’ because they will pay more attention to their tinnitus in quiet environments. This includes turning on a radio, listening to music or a podcast, turning on a fan, or using a sound generator when trying to fall asleep at night or when trying to concentrate, such as during work or school tasks.

A third step to take when having tinnitus is to learn stress-management techniques. Tinnitus can be incredibly annoying, frustrating, and for some people, scary when it first occurs. Psychologically-based approaches, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction and other approaches such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), help individuals manage the stress created by experiencing tinnitus. These can be learned from a counselor or psychologist, a tinnitus specialist, or from a variety of books and internet resources. For some people, stress may be a trigger for a reoccurrence of tinnitus. For others, high levels of stress can reduce their patience and increase their frustration with conditions like tinnitus. Programs like Coping Effectiveness Training (CET) teach people how to identify changeable and unchangeable stressors and how to match coping strategies with the type of stressor. For unchangeable conditions like tinnitus, people are taught that while they cannot ‘solve’ or get rid of the problem of tinnitus (given the current state of tinnitus research), they have control over their reactions to tinnitus. When people are less angry and reactive to tinnitus, they have more mental and cognitive space for the things that give them pleasure and satisfaction in life, like focusing on the goals that they want to accomplish or interacting with and helping others.

While subjective tinnitus can be annoying, distressing, and irritating, it is not life-threatening. Our brains will pay less attention to tinnitus when we embed ourselves in rich sound environments and get involved in tasks and events that capture our interest. Further, individuals can learn how to use numerous self-management techniques to increase their quality of life with subjective tinnitus until a cure is found.

Featured image: Buddhist Bells by Igor Ovsyannykov. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post What to do about tinnitus? appeared first on OUPblog.

Crime and the media in America

The modern media landscape is filled with reports on crime, from dedicated sections in local newspapers to docu-series on Netflix. According to a 1992 study, mass media serves as the primary source of information about crime for up to 95% of the general public. Moreover, findings report that up to 50% of news coverage is devoted solely to stories about crime.

The academic analysis of crime in popular culture and mass media has been concerned with the effects on the viewers; the manner in which these stories are presented and how that can have an impact on our perceptions about crime. How can these images shape our views, attitudes, and actions?

Using the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice, we looked at how crime is covered in the media and its ramifications.

Newspaper

Nowhere is the abundance of crime news coverage more evident than in the newspaper medium, which often faces fewer constraints with respect to space and time compared to other formats (television), thereby enabling more stories to be generated. Despite the fact that certain crimes are considerably more common (e.g., property crimes), violent crimes are covered much more frequently. Even still, not all violent crimes receive equal coverage. In fact, stories that are deemed sensational are not reported on the same across the board. A study examining the media coverage of mass murders between 1976 and 1996 found that newsworthiness of cases varied across space—that is, while nearly all mass killings were covered by local sources, a much smaller proportion of cases were successful in garnering national attention.

One of the many contributing factors that determine whether or not a case receives media attention is the newsworthiness of its victims. According to the researchers, these individuals were “[w]hite, in the youngest and oldest age groups, women, of high socioeconomic status, [and] killed by strangers.” Further studies have also demonstrated intersections of race, class, and gender as indicators of “worthiness.”

Research shows that with high levels of television news consumption and newspapers readership, increased fear of victimization and crime was present. Even more, local news was found to have a more significant impact on the fear of crime.

TV

In the United States in the 1970s, local “action news” formats, driven by enhanced live broadcast technologies and consultant recommendations designed to improve ratings, changed the nature of television news: a shift from public affairs journalism about politics, issues, and government toward an emphasis on profitable live, breaking news from the scene of the crime. The crime rate was falling, but most Americans didn’t perceive it that way. From 1993 to 1996, the national murder rate dropped by 20%. During the same period, stories about murders on the ABC, NBC, and CBS network newscasts rose by 721%.

At the same time, TV networks invested in crime shows. Fox’s big hit was the reality show Cops, which blended crime news and entertainment. A 1995 study of audiences for the TV show Cops revealed that viewers regarded the show as more realistic than other types of policing shows. Other studies show that viewers see reality shows as providing information, rather than entertainment. Audiences interpret crime-based reality programming as similar to the news.

Documentaries and beyond

With the success of Netflix’s Making a Murderer we have seen a public interest in criminal documentaries. Why? Within the criminal justice system, they are important not only because of the public fascination with crime and punishment, but also because the everyday workings of the criminal justice system often remain outside of the direct experience or sight of most people. This can have an impact on our notions of crime and the criminal justice system. Because popular culture is saturated with images of crime and punishment, the public relies to a greater extent on media representation to form their image of imprisonment, policing, and the criminal justice system more broadly.

Indeed, this crime “genre” has found popularity even in the newest of media formats. The popular podcast Serial presented in its first season an investigative journey into a local murder case from Baltimore County, Maryland in 1999.

In the 1960s a term was popularized to describe our society’s fascination with violence and crime as a public spectacle called “wound culture.” It is this odd pull towards the abject that has been at the heart of American media. As the future of media looks to integrate social media and news information more and more, there are serious questions to consider. Will algorithms designed to feed us content we “like” lead to even more consumption of crime news? How will that skew our perception of crime in America? Will an illusion of a crime infested America affect our politics?

Featured image credit: Watch tv by Broadmark. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Crime and the media in America appeared first on OUPblog.

How Atari and Amiga computers shaped the design of rave culture

I can still recall the trip to Bournemouth to get the Atari ST “Discovery Pack.” The Atari ST was a major leap forward from our previous computer, the ZX Spectrum, offering superior graphics and sound capabilities. It also had a floppy disk drive, which meant it was no-longer necessary to listen to extended sequences of noise and coloured bars while the game loaded (this was an exercise in patience at the time, though retrospectively these loading sequences seem more interesting due to the similarities with experimental noise music!) Whereas the uses of today’s modern computers often seem very prescriptive, at least at a surface level, the Atari ST “Discovery Pack” not only came with pre-packaged games, but also included programming tools—opening up a world of possibility. My older brother was soon programming games, which I would assist by creating pixel art in NEOchrome. With the addition of Stereo Master, which included a cartridge with audio line-in, we were soon able to experiment with recording and manipulating digital audio samples, while trackers could be used to sequence music. Later on, I also got to experiment with other graphical packages like GFA Raytrace and Jeff Minter’s Trip-a-Tron light synth.

Of course, we were not the only ones who enjoyed this period of creative experimentation and excitement at the possibilities of computing. Around this time there was something of a golden age, with many innovative software houses and bedroom coders creating games and demoscene disks that have since gained legendary status. Even the cracked Pompey Pirates or Automation menu disks were exciting, with their colourful graphics, music, and irreverent streams of scrolling text. What is also interesting is that the futuristic excitement about computers in this period also spread out into other areas of music and culture. Computers provided the tools for low-cost music production, with trackers (a type of music sequencing software) such as OctaMED on the Amiga, and the first version of Cubase on the Atari, which also included an in-built MIDI port.

For the burgeoning rave scenes of the late 1980s and 1990s, these computers—together with drum machines, synthesizers, digital samplers and workstations—provided inexpensive solutions that were adopted by many underground music producers. For example, Urban Shakedown/Aphrodite, Omni Trio, DJ Zinc, and Bizzy B were among those who used OctaMED. As a result, the design and aesthetics of a great deal of rave music from this period such as breakbeat hardcore, jungle, and drum and bass, can be associated with these computers and the tracker interface. Indeed, in the case of jungle—a style of dance music that revolves around the intricate slicing and rearranging of funk breakbeats—tracker sequencers have remained enormously popular to the present day, with producers such as Bizzy B and Venetian Snares continuing to favour modern versions such as Renoise.

“While the music and graphics from this period remain interesting in their own right, recently we have also seen new artistic movements that mine these aesthetics and reconfigure them in new ways.”

Yet it was not only the sonic design of rave culture that bore the mark of home computers—so did the visual design. As explored in the 1999 documentary Better Living Through Circuitry, graphic design packages provided the means to create event fliers, record sleeves, and VJ mixes. Just as hardcore rave tracks sampled and remixed mainstream culture—turning children’s TV themes into allusions to drug-fuelled raving—graphics packages enabled similarly subversive détournements of corporate logos. Meanwhile, software such as NewTek’s Lightwave 3D and the Video Toaster, a video production expansion for the Amiga, allowed designers to construct psychedelic fantasias that depicted ecstatic virtual rave utopias. Tools such as these allowed the production of Studio !K7s classic X-Mix series of VJ mixes; The Future Sound of London’s stunning Lifeforms visuals; and Alien Dreamtime by Spacetime Continuum with Terence McKenna, the latter of whom was one of the key counter-culture philosophers of the 1990s.

In no small way then, computers such as the Atari, the Amiga, and their successors, were vital forces in shaping large sections of 1990s rave culture. While the music and graphics from this period remain interesting in their own right, recently we have also seen new artistic movements that mine these aesthetics and reconfigure them in new ways. For instance, vaporwave constructs audio-visual experiences of surrealistic nostalgia for the synthetic utopias of 1990s computer graphics. Vaporwave and its The Simpsons-themed offshoot, simpsonswave, are like spaced-out, melancholy dreams of the 1990s, recorded on a VHS player with bad tracking. These genres are both narcoleptic hymns to a lost age of techno-utopianism, and psychedelic video fodder for America’s double cup (purple drank) codeine subculture. Elsewhere, the retro computer aesthetics of rave culture are also being revisited in street-wear, as can be seen through the designs and promotional media of Kenzo, Palace skateboards and Fun Time (to name but three). Through these various post-millennial permutations, we see not only how 1990s computers such as the Atari and Amiga shaped a golden era of rave culture, but also how those subcultural aesthetics have had enduring popularity, as subsequent generations seek the unattainable ecstasies of bygone techno utopias.

Featured image: Digital artwork “Vaporwave Island” by Jon Weinel, 2018. Image used with permission.

The post How Atari and Amiga computers shaped the design of rave culture appeared first on OUPblog.

April 4, 2018

Etymology gleanings for March 2018: Part 2

Thanks to all of our readers who have commented on the previous posts and who have written me privately. Some remarks do not need my answer. This is especially true of the suggestions concerning parallels in the languages I don’t know or those that I can read but have never studied professionally. Like every etymologist, I am obliged to cite words and forms borrowed from dictionaries, and in many cases depend on the opinions I cannot check. This holds for the Baltic group and any non-Indo-European language. But I am always grateful for thoughts about them; they come from native speakers and can therefore be trusted. Other than that, I do have a few things to add to the March gleanings.

So long

No doubt, sail on would be an ideal source of so long, but, as we cannot prove its existence, this hypothesis has no potential. Scandinavian så lenge ~ så længe has often been proposed as the etymon of the English phrase. Here we encounter a familiar problem: where could the Swedes or Norwegians, or Danes have picked up this greeting, or is it their own invention? Let me repeat the main points: the phrase was recorded relatively late and some facts indicate its American (“coastal”) origin.

Now the Malayan connection. In my post for 7 March 2018, I mentioned a 2004 article on this subject. Its author is Alan S. Kaye, an expert in Semitic (and several other) languages. He wrote his article in response to L. M. Boyd’s trivia column, and this is what he says: “In his column for February 23, 2004… Boyd asserts that the common colloquial or slang phrase so long derives from the speech of British soldiers in Malay Peninsula, who heard Malay saying salong, which they in turn, being Muslim, borrowed from the well-known Arabic greeting salaam….” Kaye consulted a reliable dictionary with the following result: “I did not locate any Malay word salong used to mean ‘farewell’…. I also found salam ‘greeting…. [and] became suspicious of Boyd, thinking that he had succumbed to folk etymology…. One thing still bothers me, though. Since I cannot locate the etymological connection to Malay and British soldiers, I am left wondering where Boyd read this.” I share his wonder. Other than that, knowing nothing about Malay, I can only sell his conclusion for what I bought it, as they say in Russian.

This is Malaysia, so far, so long…. Image credit: Location of Malaysia via Vardion. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

This is Malaysia, so far, so long…. Image credit: Location of Malaysia via Vardion. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.How old is Old English?

I did not mean to return to the ever-recurring comments on English versus Greek, because what I could say about this matter I have said at least twice, but one point may be worth mentioning. The age of no language can be determined. Only Old English texts are late. English is a member of the Germanic group, and Germanic means that we are dealing with an Indo-European language after it underwent the First Consonant Shift, developed a system of weak verbs, and acquired a few other well-known features. To put it differently, as long as phonetics is concerned, Germanic is Indo-European with an accent, just as German is Germanic with an accent (because of the Second Consonant Shift and some other changes). In our theory, all languages are coeval; only individual phenomena succumb to chronology. Therefore, neither Sanskrit, Greek nor Latin enjoys seniority when it comes to etymology. Assuming that the Indo-European hypothesis has some reality behind it (despite the fact that we don’t know who the oldest Indo-Europeans were, where they lived, etc.), words belonging to this family are called related only if they can be shown to be related. Greek phrēn and Engl. brain are incompatible, because neither their vowels nor their consonants match. To put it differently, we are unable to reconstruct the protoform from which the two words acquired the shape known to us. Borrowing brain from Greek is out of the question. If phrēn had existed in the speech of Germanic speakers centuries or millennia before it surfaced in texts, it would not have become brægen. At least we are unaware of any reasons why it should have changed in this direction. Besides, the English word is local, with cognates only in German and Dutch. Most probably, it was coined in that speaking area, and the etymologist’s task is to try to explain how it came up.

I am a bear of very little brain, and long words bother me. Image credit: Winnie The Pooh by Darrell Taylor. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

I am a bear of very little brain, and long words bother me. Image credit: Winnie The Pooh by Darrell Taylor. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.The l ~ d variation (Latin lacrima ~ dacrima) in connection with the word for “tear from the eye”

Yes, indeed, the variation is dialectal, but this fact does not explain anything. Reference to other languages shows that l can indeed be substituted for d, but that we knew before we launched our query. The nature of the variation (word-initially!) also has to be explained. The number of words affected by d ~ l in Indo-European is vanishingly small. In Classical Greek, d was certainly a stop, not a th-like spirant, while l must have been close to Modern Greek l. It does not seem that Greek distinguished between two sense-differentiating l’s (hard and soft, as in Russian, or “thin” and “thick,” as in some Norwegian dialects), so the riddle remains unsolved.

Think global, etymologize local. Image credit: A chimpanzee brain at the Science Museum London by Gaetan Lee. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Think global, etymologize local. Image credit: A chimpanzee brain at the Science Museum London by Gaetan Lee. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.A short disquisition on vowel length in English and especially German

I would not have returned to this thorny question, but for a long comment. Those who learn German from books are told that some German vowels are short, while others are long. The parade example is bieten “to offer” versus bitten “to ask for something.” This distinction is obvious in so-called open syllables (that is, in syllables with no consonant following the vowel), and especially in dissyllables, as in the words cited above, but, if you ask an unschooled native speaker of German whether the vowel is long in words like Fluss “river” or Fuß “foot,” the response does not come at once. The situation in English is much worse. Hardly anyone defines the difference between bit and beat in terms of vowel length. Very long ago, the great German scholar Eduard Sievers defined the difference between such vowels in terms of “extendible” versus “non-extendible.” In German, this opposition works well. Even more efficient (as I know from my teaching experience) is the request to stop in the middle of the word: in Engl. beater, a pause after bea– is possible (the vowel is “long”), while in bitter a stop is impossible (the vowel is “short”). The situation is analogous in German bieten versus bitten. That is why I wrote that making people (in German) ponder the vowel length is sometimes a rather hard task. This discussion came up in connection with the relatively recent German spelling reform. It would be interesting to hear what our German colleagues think about such things.

A lachrymose situation: Is that book called Lorna Doone of Dorna Loone? Image credit: “Poses Female Education Posing Caucasian What” by NDE. CC0 via Pixabay.

A lachrymose situation: Is that book called Lorna Doone of Dorna Loone? Image credit: “Poses Female Education Posing Caucasian What” by NDE. CC0 via Pixabay.Separate words

♦Yes, liver, the alleged source of emotions and passions, would be a good cognate of the verb to live, but the desired connection cannot be made out. My reference to fast livers was a joke: I had never discussed those words.

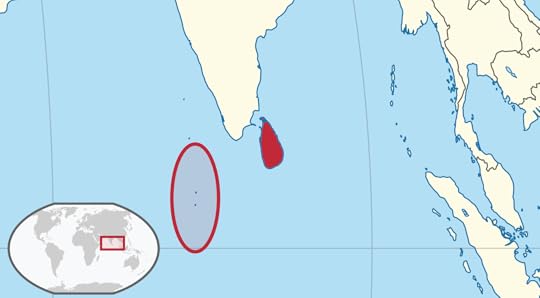

♦In one of the comments, a suggestion was made that the etymon of path should be sought in Tamil, rather than Sanskrit (see the post for 4 November 2015). This may be true, but, as told in the post, the origin of path is obscure. The Indo-European form cannot be reconstructed (initial p– should go back to non-Germanic b-, but outside sound-imitative and sound-symbolic words, b– was practically nonexistent in the reconstructed Indo-European). Prehistoric contacts with Indo-Iranian speakers make one think of Scythians. Yet their ancient language has not come down to us.

Tamil is spoken here. Any road from these parts to the English word path? Image credit: Sri Lanka in its region by TUBS. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Tamil is spoken here. Any road from these parts to the English word path? Image credit: Sri Lanka in its region by TUBS. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.♦Are carouse, carousel and German Grusel– “horror” related? See the post for 5 April 2017 (carousal). No, they are not. Carouse goes back to German gar aus “no heel taps!” (as explained in the post referred to above). Grusel-, which is akin to Grauen and Grausen (approximately the same meaning), is a Germanic word (compare Engl. gruesome), while carousel is Romance (Italian). For some interesting information see Friedrich Fried’s 1964 book A Pictorial History of Carousel.

♦♦A query from our reader. “I read a lot of ‘sceptical’ material online and wondered recently about the source of the word woo, used derogatorily to refer to the uncanny, the mystical, etc. I found that it is generally believed that the usage is from something like ‘woo-oo-oo’ in imitation of the eerie background music of films.” Any ideas about this piece of voodoo etymology? I have some but will keep them to myself (for the time being).

Featured image: Grandfather, father, and son. This is not an image of any three Indo-European languages. Image credit: “Family Generations Great-Grandparents Son Father” by brfcs. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Etymology gleanings for March 2018: Part 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

Wonder, love, and praise

T.S. Eliot admired the way seventeenth-century poets could bring diverse materials together into harmony, and for whom thought and feeling were combined in a unified sensibility. However, he famously described a kind of dissociated sensibility that set in at the end of the century with the advent of mechanical philosophy and materialist science. This made it more difficult to hold together the spiritual with the material. What, after all, is the response of a unified sensibility (of thought, feeling, and religious devotion) to particulate matter in void space obeying abstract mathematical laws?

When the evangelical movement emerged in the eighteenth century, it was among the first generation to accept the basic postulates of Newtonian science. For example, the young Jonathan Edwards came across the new science during his years as a student at Yale College. Newton himself contributed a copy of his Principia and Opticks to the collection of volumes given to establish the library at the infant college, and these books were taken out of their crates in 1718 (in the middle of Edwards’s undergraduate education). Newtonian physics quite literally arrived on his doorstep. Edwards was soon keeping his own science notebooks about “Things to be Considered and Fully Written About.”

Evidently there were a lot: why thunder a great way off sounds “grum” but nearer sounds very sharp; how arterial blood descends and venal blood ascends according to the laws of hydrostatics; why the fixed stars twinkle, but not the planets; why we need not think the soul is in the fingers just because we have feeling in our fingers; why the sea is salty; and the list goes on. There seemed no end to Edwards’s intellectual curiosity about the natural world.

On the other side of the Atlantic, John Wesley also tracked developments in science in multiple editions of his Survey of the Wisdom of God in the Creation (1763). But his preface to each edition ended the same way. He hoped that his account would serve to “warm our hearts, and to fill our mouths with wonder, love, and praise!”

This note of devotion in response to the world described by science suggests there were still religious people seeking after the kind of unified sensibility that Eliot found in earlier poets. It seems piety itself did a kind of metaphysical work above its pay grade as a number of evangelical poets, scientists, artists, and theologians came to see the natural world as radiant with the presence of God.

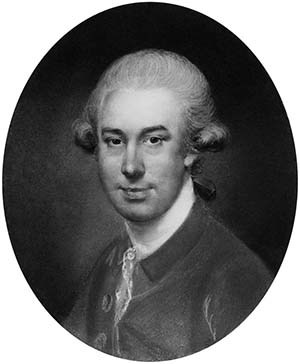

John Russell, self-portrait c. 1780 by John Russell. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

John Russell, self-portrait c. 1780 by John Russell. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. For Wesley, conversion changed everything. Renewed by the Spirit of God, the human person could be conscious of God’s presence everywhere in the material world: “They see Him in the height above, and in the depth beneath; they see him filling all in all. The pure in heart see all things full of God.” This was now directly counter to any metaphysical naturalism: “We are to see the Creator in the glass of every creature … look upon nothing as separate from God, which indeed is a kind of practical atheism.” Wesley even drew upon the language of an earlier age, saying that God holds all things together as the anima mundi, for he “pervades and actuates the whole created frame, and is in a true sense the soul of the universe.”

The figure among the early evangelicals who best captures this unified sensibility in the age of science is the artist John Russell (1745-1806). A member of the Royal Academy and the foremost pastellist of his generation, he showed more than 300 pictures in the Academy’s exhibitions and could fetch the same price for a portrait as its president Joshua Reynolds. For all his artistic success, though, he was an ardent and outspoken evangelical believer who would hold his aristocratic sitters captive “to have the opportunity of speaking about Jesus.” His passions extended beyond art and religious devotion too. For more than two decades, he made detailed lunar observations for some six hours a night with his telescope, typically staying up until two or three in the morning. The Museum of the History of Science in Oxford has a collection of 180 of his studies, and an exquisite monumental pastel from 1795 of a gibbous moon hanging in empty space.

The Face of the Moon by John Russell. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Face of the Moon by John Russell. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Since he first saw the moon through a telescope and it took his breath away Russell was especially observant of the “effect” of different conditions of light and darkness on the features of the moon. His artistic training meant he was concerned with representing well the aesthetic qualities of what he called simply “this beautiful Object,” and it was this very mode of attention that also enabled him also to see things others had missed. Not yet, then, was there the suggestion of two kinds of truth, the publicly-accredited truths of hard science, and the softer, more subjective truths of art.

There is one detail in Russell’s lunar studies that offers an especially delightful illustration of his union of art and science. The Promontorium Heraclides on the moon’s surface juts out into the Mare Imbrium and had been noticed under a certain light to look like the outline of a woman’s head in profile. Between 1787 and 1789, Russell did his own sketches of the “maiden in the moon.” The beauty and grace of these studies may be placed side by side with specimens of the detailed cartographic calculations he made with his homemade micrometer, showing his exact measurements of the features on the moon. Close observation was put in the service of both truth and beauty. There was a combination of art and science, grace, and precision, in all his lunar observations. And perhaps devotion, too.

With its delicately feathered wings, Russell’s “moon maiden” seems to merge into the figure of an angel. Although this may have been simply an element of fancy, it would not be beyond the unified sensibility and religious devotion of an artist who was lost in “wonder, love, and praise.”

Featured Image: “Full Moon photograph taken 10-22-2010 from Madison, Alabama, USA” by Gregory H. Revera. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Wonder, love, and praise appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers