Oxford University Press's Blog, page 262

April 15, 2018

“The American People”: current and historical meanings

The People, sir, are a great beast.”

–Alexander Hamilton

Virtually all US politicians are fond of “The American People.” Indeed, as the ultimate fallback stance for any candidate or incumbent, no other quaint phrase can seem so purposeful. Interesting too, is this banal reference’s stark contrast to its original meaning.

That historic meaning was entirely negative.

Unequivocally, America’s political founding expresses general disdain for any truly serious notions of popular rule. For Edmund Randolph, the evils from which the new country was suffering originated in the “turbulence and follies of democracy.” Elbridge Gerry spoke of democracy as “the worst of all political evils,” and Roger Sherman hoped that “the people…have as little to do as may be about the government.” Hamilton, the likeable subject of today’s most popular musical on Broadway, charged that the “turbulent and changing” masses “seldom judge or determine right,” and diligently sought a “permanent” authority to “check the imprudence of democracy.”

For Hamilton, such imprudence was inherent and irremediable.

For Hamilton, the American People represented a “great beast.”

In a similar vein, George Washington soberly urged convention delegates not to produce a document solely “to please the people.” For him, as well, any search for public approval was anathema.

Today, Americans casually neglect that the country’s founders had a conspicuously deep distrust of democratic governance. Accordingly, warned the young Governeur Morris, “The mob begin to think and reason, poor reptiles . . . They bask in the sun, and ere noon they will bite, depend on it.”

Furthermore, President George Washington, in his first annual message to the Congress, revealed similarly compelling apprehensions about any genuine public participation in government. The American people, he sternly warned, “… must learn to distinguish between oppression, and the necessary exercise of lawful authority . . .”

Much as Americans might not care to admit it, the country’s founding fathers were largely correct in their expressed reservations, but probably for the wrong reasons. In the United States, “We the people” have displayed a more-or-less consistent capacity for deference to “lawful authority.” Still, this “people” has also demonstrated a more-or-less persistent unwillingness to care for themselves as authentic individuals; that is, as as meaningfully recognizable “good citizens.”

Now it is time for candor, especially in the Trump Era. A “mob” does effectively defile any presumed American “greatness,” but it is not the same mob once feared by Hamilton, Sherman, and Morris.

It remains a dangerous mob nonetheless.

Who actually belongs to the dangerous American mob? In essence, they are rich and poor, black and white, easterner and westerner, southerner and mid-westerner, educated and uneducated, young and old, male and female, Jew, Christian, and Muslim, Hindu and Buddhist and atheist. It is, in some respects, precisely as the founding fathers had earlier feared, a democratic mob. Yet, its most distinguishing features are not poverty or any lack of formal education. Rather, they concern the absence of any decent regard for genuine learning.

More than anything else, as should be readily apparent from social media, America is all about “fitting in,” about resisting personal estrangement from the mass at absolutely all costs.

In Donald Trump’s America, we have gone from “bad to worse.” The overriding goal for literally millions has become painfully obvious. This goal is a presumptively comforting presidential dispensation to chant pure nonsense, endlessly, as ritualistic cheerleaders, in chorus. Comforted by such rhythmic and repetitive primal chanting (one should think here of the marooned English schoolboys in William Golding’s Lord of the Flies), citizens freely abandon any more meaningful responsibilities to really understand what is being cheered.

“We’ll build a beautiful wall, with a beautiful door, and Americans will be safe.” Of course, the very country that is being blamed for America’s own ills will obligingly pay for this “beautiful wall.”

In significantly large measure, the American People now fulfill early Roman appraisals of the plebs; that is, of an unambitious mob, one wishing to learn only what is “practical,” a commoditized mass roughly equivalent to the ancient Greek hoi polloi a usefully malleable “herd” (think both Nietzsche and Freud, who preferred “herd” to “mass”) that viscerally celebrates the demeaning sovereignty of unqualified persons.

A summation of such fulfillment was already known to America’s founding fathers, primarily by way of Livy: “Nothing is so valueless,” said Livy, “as the minds of the multitude.” Recalling this ancient Latin author, America’s core enemy is today an insistent intellectual docility, a grimly uninquiring national spirit that not only knows nothing of truth, but also wants to know nothing of truth.

In his Notes on Virginia, Thomas Jefferson once proposed an improved plan of elementary schooling in which “twenty of the best geniuses will be raked from the rubbish annually.” Today, of course, it is simply inconceivable that any president or presidential aspirant could refer to his fellow Americans as “rubbish.” Yet, this openly crude analogy expressed the unvarnished sentiment of America’s most famous early “populist,” the founder and future president who drafted the Declaration of Independence.

Going forward, the “American People” have only one overriding obligation; that is, to disprove both Alexander Hamilton and Donald Trump by somehow embracing a new national political ethos, one inspired not by a perpetual fear of severance from the warmly-submissive American mass, but by a much more intentional cultivation of personal intellect and public responsibility. Plainly, this indispensable embrace will take time – arguably, perhaps, even more time than is still actually available (One should be reminded here of Bertrand Russell’s trenchant observation in Principles of Social Reconstruction (1916): “Men fear thought more than they fear anything else on earth – more than ruin, more even than death.”) — but there is no alternative. For The American People, this eleventh-hour embrace may effectively represent its last graspable chance for personal and collective survival.

Featured image credit: American flag and sparkle by Trent Yarnell. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post “The American People”: current and historical meanings appeared first on OUPblog.

April 14, 2018

What’s the deal with genetically modified (GM) foods?

It’s complicated; but here is a quick summary of what the controversy over genetically modified foods is all about.

GM engineering involves reconfiguring the genes in crop plants or adding new genes that have been created in the laboratory.

Scientific modification of plants is not something new. Since time began, nature has been modifying plants and animals through natural evolution, meaning that the plants and animals that adapt best to the changing environment survive and pass their genes on to their offspring. Those that are least fit do not survive. Farmers, too, have been helping nature improve crops for generations by saving the seeds of the best tomatoes and apples to use for next year’s crop. This is a kind of genetic selection—the most favorable plants succeed.

Seed companies have been contributing to this genetic strengthening, too. Today’s seed catalogs show traditional genetic selection at its finest, promising flowers with bigger blooms, tomatoes that ripen early, and new varieties of old species. Genetic selection has always been cultivated, first by nature and later with help from flower growers and farmers. It’s nature at its best.

But here’s the problem—today’s genetic tinkering is not being undertaken by farmers. It is being driven by chemical (i.e., pesticide) manufacturers and plant geneticists, and it is proceeding on a macro scale. The chemical manufacturers’ goal is not to produce a tastier apple, a juicier tomato, or more nourishing corn, but rather to modify food crops, such as corn and soybeans, so that the crops will be resistant to the pesticides that these same companies make. Then, when it comes time to weed vast tracts of planted corn or soybeans, the agro-business can spray the pesticide-resistant crops with the chemical company’s product to kill the weeds—rather than perform the tedious task of mechanical weeding. The weeds die, the crops live, and the pesticide company makes money. At first glance it appears to be an efficient way to weed a big field.

But those crops are our food. They go into the cereals, snacks, and processed products that we and our kids eat. Won’t crop plants absorb some of the pesticides that are sprayed on them while they’re growing—especially if more and stronger pesticides are being used on them? All pesticides and herbicides have potential to be toxic to humans, and especially to children.

And what happens when the “survival of the fittest” kicks in? Won’t some weeds figure out how to thwart the herbicides? Will this mean that the industrial farmer has to spray more and stronger herbicides to get the job done?

Despite promises by chemical manufacturers that weeds would not become resistant to Roundup (glyphosate, the herbicide most widely used in the United States on genetically modified food crops), resistant weeds are now rampant. It is reported that weeds resistant to Roundup cover more than 100 million acres across several dozen US states. According to the World Health Organization, Roundup is a probable human carcinogen a chemical judged probably capable of causing cancer in humans. To combat the spread of herbicide-resistant weeds, larger and larger quantities of this probable cancer- causing herbicide are now being used. Use of glyphosate has increased in the US by 2,500% over the past 25 years.

To combat the problem of glyphosate-resistant weeds, chemical companies are now engineering GM seeds to withstand not only to glyphosate, but also to be resistant to two additional, older herbicides: 2,4 D (a component of the notorious Agent Orange, used during the Vietnam War to defoliate jungles) and dicamba (a pesticide highly toxic to birds and other living things). These highly toxic chemicals are now beginning to be added into the chemical regimen sprayed on fields of corn, soybeans, and other commercial crops. In turn, US residents can expect that measurable levels of these toxic chemicals will carry over into the foods produced from these heavily treated crops—with additional chemicals added to pesticide protocols potentially still to come.

Chemical manufacturers have long portrayed the goal of GM foods as being the provision of more nutritious crops capable of feeding the world. But a 2016 New York Times report, “Uncertain Harvest,” contested this claim, reporting that GM foods crops have actually failed to increase food production or the robustness of crops being harvested. GM crops have also failed to reduce pesticide use, amounting to another undelivered promise made by pesticide manufacturers.

In sum, genetically modified foods are not inherently unhealthy in themselves. The problem is the company they keep—the additional layers of pesticides of ever-increasing toxicity—pesticides that farmers and growers are beholden to because their seeds are genetically modified to accommodate them. As this GM-industrial complex continues to proliferate, the world’s food supply grows increasingly dependent on GM seeds, which in turn increases dependence on chemical fertilizers and pesticides. These chemicals, as discussed at length, are toxic to humans.

Featured image credit: CC0 Public Domain via pxhere.

The post What’s the deal with genetically modified (GM) foods? appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know the US Supreme Court? [quiz]

The Supreme Court is at the heart of the United States of America’s judicial system. Created in the Constitution of 1787 but obscured by the other branches of government during the first few decades of its history, the Court grew to become a co-equal branch in the early 19th century. Its exercise of judicial review—the power that it claimed to determine the constitutionality of legislative acts—gave the Court a unique status as the final arbiter of the nation’s constitutional conflicts.

From the slavery question during the antebellum era to abortion and gay rights in more recent times, the Court has decided cases brought to it by individual litigants, and in doing so has shaped American constitutional and legal development.

But how well do you know the Supreme Court? Test your knowledge of the history of the US Supreme Court:

Featured image: Supreme Court. Public Domain via Unsplash.

Quiz Image: Supreme Court of the United States. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post How well do you know the US Supreme Court? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the month: Adam Smith [Timeline]

This April, the OUP Philosophy team honors Adam Smith (1723-1790) as their Philosopher of the Month. Smith was an eminent Scottish moral philosopher and the founder of modern economics, best-known for his book, The Wealth of Nations (1776) which was highly influential in the development of Western capitalism. In it, he outlined the theory of the division of labour and proposed the theory of laissez-faire. Hence instead of mercantilism, Smith saw that government should not interfere in economic affairs as free trade increased wealth. Smith also wrote the philosophical work The Theory of Moral Sentiment, in which he considered sympathy as the most important moral sentiment – the knowledge that one shares others’ feelings and our ability to understand the situation of the other person – and this fellow feeling we have with others help us to know whether our action or the action of another person is good or bad and conducive towards some good end.

Smith was more of an Epicurean rather than a Stoic. He shared David Hume’s views on morals and economics and inherited from his teacher Francis Hutcheson the spectator theory of virtue, a form of psychological naturalism which views moral good as a particular kind of pleasure, that of a spectator watching virtue at work.

For more on Adam Smith’s life and work, browse our interactive timeline below:

Featured Image: The painting of Edinburgh characters in the eighteenth century. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Philosopher of the month: Adam Smith [Timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

April 13, 2018

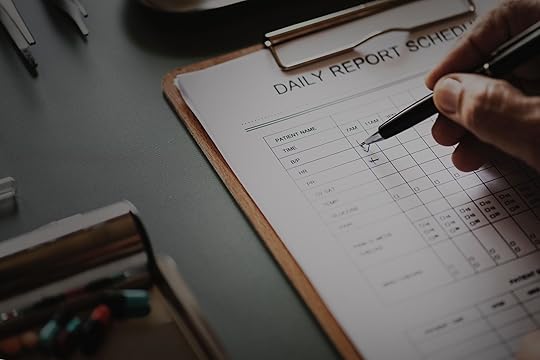

Better health care delivery: doing more with existing resources

The healthcare sector faces challenges which are constantly escalating. Populations are growing worldwide and so is the share of the elderly in society. There is a constant proliferation of new medications, diagnostic methods, medical procedures and equipment, and know-how. This huge progress greatly improves the quality of medical treatment but at the same time increases its costs. Governments and authorities are allocating ever growing budgets to healthcare systems but the increased budgets do not cover the increased costs of providing quality healthcare to the public. It is becoming clear that there is an urgent need for practical knowledge and effective tools for people in managerial as well as staff positions.

In response to this need, there are several methods and simple tools that can ease the challenges experienced by every health care organization in the modern day, which don’t have to cost more money. In fact, one can do much more with the same resources in terms of throughput, response time, and quality by using simple practical tools and techniques, all based on common sense. This is achieved through a system view that touches upon issues of performance measures, operations management, quality, cost-accounting, pricing, and above all, value creation and enhancement. Every manager, at every level, within a health care organization will be able to implement immediate actions resulting in relatively rapid improvement in most performance aspects of the organization. The focus is on reducing waste and avoiding non-value-adding activities.

This is the essence of the “Lean concept.” Lean is a philosophy: based upon tools that are simple, easy to comprehend and use, and have already achieved amazing results in many healthcare organizations. It is the use of the Theory of Constraints (TOC), a management paradigm, along with other focusing tools such as the Focusing Table, the Focusing Matrix, the Complete Kit concept, and Pareto analysis that provide the highly added-value for healthcare managers. This is especially critical in face of the problems with the Affordable Care Act and other emerging healthcare reforms.

Image Credit: Writing by rawpixel.com. CC0 via Unsplash.

Image Credit: Writing by rawpixel.com. CC0 via Unsplash.One of the most powerful tools to improve a hospital, laboratory, or clinic, is the small batch concept. People have been trained to use “economies of scale” to avoid possible costly turnovers, resulting in working with large batches. Reducing batch size can do wonders for processes and organizations. Using small batches, one can dramatically reduce response times (especially in laboratories and imaging services).

All the above mentioned tools help break the myth of the “input-output” model where you need more inputs. One can increase throughput, reduce response times, and increase quality, all with using existing resources.

It is difficult to dismiss the amazing achievements that many hospitals have made while using only existing resources. They have shown that an increase throughput in operating rooms by 10-20% and reduction of response times in places like emergency departments and clinics by 20-40% is a sustainable goal—realistic rather than aspirational. For example, in the operating room of the ophthalmology department in a public hospital, within only four months, the number of operations increased by 43%, waiting time for surgery decreased by 41%, all this with a significant improvement in quality. Further success stories will follow.

A clear example of the successful application of the Theory of Constraints can be seen in the below case study of a General Hospital in the United Kingdom.

The objectives were:

1. Discharge patients from the emergency arena in less than four hours

2. Reducing delayed admissions that exceeded 12 hours

The results within one year, following the application of TOC, were:

· 35% improvement in less than four hours throughput in the emergency arena from 68.0% to 92.2%

· No delayed admissions that exceeded 12 hours

· 91% reduction in delayed admissions that exceeded four hours

A large Private Hospital in Tel Aviv, Israel, saw impressive results that were achieved within just nine months using TOC:

· Number of operations increased by 20%

· Profits nearly doubled (fixed costs accounted for 80% of costs so additional operations were very profitable)

· Waiting times for operations decreased by 20%

· Queues for operations and imaging tests decreased by more than 20%

· Improved clinical quality and service quality

According to the CEO of the hospital, the three tools with the most impact were eliminating dummy constraints, using specific contribution, and working with complete kits. These tools are used in the OR as well as in the ED, internal medicine wards, laboratories, and imaging services, in large healthcare organizations as well as in small and medium size ones.

Managers of hospitals and clinics can do much more using only existing resources. The way to succeed in implementing changes and getting successful results lies in integrating several tools and philosophies, such as combining TOC and Lean together. TOC can achieve fast results by focusing on the few important points. On the other hand, Lean enables teams to analyze and improve processes. By combining both managerial philosophies, TOC can point out the areas to improve, as Lean can provide tools to get the work done.

Featured Image Credit: “A row of chairs in the hospital hallway” by hxdbzxy. Via Shutterstock .

The post Better health care delivery: doing more with existing resources appeared first on OUPblog.

April 12, 2018

Revered and reviled: George Washington’s relationship with Indian nations

During George Washington’s presidency, Indian delegates were regular visitors to the seat of government. Washington dined with Cherokees, Chickasaws, Creeks, Kaskaskias, Mahicans, Mohawks, Oneidas, and Senecas; in one week late in 1796, he had dinner with four different groups of Indians on four different days—and on such occasions the most powerful man in the United States followed the customs of his Indian visitors, smoked calumet pipes, exchanged wampum belts, and drank punch with them.

Washington knew what history has forgotten: Indian nations still dominated large areas of the North American continent, European nations courted their allegiance, and that the infant United States was still a precarious proposition. The presence, power, and foreign policies of Indian nations affected Washington’s life at key moments, shaped the course of American history during his lifetime, and posed a major challenge for the young republic and its first president. Washington’s primary goal as president was to secure the future of his young republic and build a nation on Indian land. In that, he succeeded. His second goal—and it was a distant second—was to establish just policies for dealings with Indian peoples.

Just months into his presidency, Washington declared that the “The Government of the United States are determined that their Administration of Indian Affairs shall be directed entirely by the great principles of Justice and humanity.” At the same time, Washington’s entire Indian policy and his vision for the nation depended on the acquisition of Indian lands. Washington and his Secretary of War Henry Knox agreed that the most honorable and least expensive way to get Indian land was to purchase it in a fair treaty. The Constitution gave the president treaty making authority and required that treaties be ratified by 2/3 majority vote in the Senate. Washington told the Senate that that included Indian treaties as well. Once ratified, Indian treaties became the law of the land. Offering tribes a fair price for their land and extending to them the benefits of American civilization, Washington hoped, would allow the United States to expand with minimal bloodshed and at the same time treat Indian peoples with justice.

“The father of the country was also, in many ways, the father of America’s tortuous, conflicted, and often hypocritical Indian policies.”

But if, as they often did, Indians refused the offer, the politicians felt there was no choice but to wage war against them. During the Revolution, Washington sent armies into Iroquois country that resulted in forty burned towns, orchards cut down, and 1600,000 bushels of corn destroyed. In this, as in so much else, the first president set precedent. The father of the country was also, in many ways, the father of America’s tortuous, conflicted, and often hypocritical Indian policies. After he dispatched armies to ravage their country during the Revolution, the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois called him “Town Destroyer.” In 1792, six months after returning from treaty negotiations in Philadelphia, the Cherokee chief Bloody Fellow declared “Congress are Liars [and] general Washington is a Liar.” Yet Washington also offered what he saw as a path to a better future for Indian people who made peace and adopted American ways of living, and many Cherokees followed that path. Looking back from the 1820s and ‘30s when the United States was riding roughshod over its treaties in a rush to relocate eastern Indian peoples west of the Mississippi, the Cherokee chief John Ross remembered with reverence the first president who had dealt justly with Indian nations; he named his son George Washington.

Washington aspired to a national Indian policy that might somehow reconcile taking Native resources with respecting Native rights even as the nation expanded across Indian homelands and ignored Indian treaty rights. In that, of course, he failed, and his failure has been America’s failure. In the end, Washington’s story in Indian country became an imperial narrative; it could hardly have been otherwise given the goals he set and the forces he helped set in motion. Assaults on Native resources and rights have continued from Washington’s day until today, but not all subsequent presidents have struggled as he did with the inherent contradictions of the nation’s Indian policies.

Featured image credit: “The life of George Washington (1848) (14754656546)” by Internet Archive Book Images. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Revered and reviled: George Washington’s relationship with Indian nations appeared first on OUPblog.

Animal of the Month: the lesser known penguins

Penguins have fascinated zoologists, explorers, and the general public for centuries. Their Latin name—Sphenisciformes—is a mixture of Latin and Greek derivatives, meaning ‘small wedge shaped’, after the distinctive form of their flightless wings. The genus of penguins comprises more than just the famous Emperors of the Antarctic, and while public awareness is growing, many of the seventeen extant members of this bird family, their habitats, and threats to their survival, remain relatively unknown.

This April, to celebrate our Animal of the Month, we explore four of the lesser known members of the penguin family tree.

Adélie Penguin

The Adélie Penguin is one of the most southerly venturing species’ outside of the tundra-dwelling Emperor Penguins. Their colonies are found all across the Antarctic coast, with one ‘super-colony’ of an estimated 1.5 million birds in the remote Danger Islands near South America, visible even from space.

The species was named after the wife of French explorer Jules Dumont d’Urville, the first European explorer to discover the penguins in the 19th Century. Since the 1970’s, the Adélie penguin has experienced a more than a 50% population decline in the vicinity of Anvers Islands, and are listed as a near threatened.

The behavioural ecology of Adélie Penguins is one of the most widely studied of all penguins, and many face the human interference of researchers handling adults, hatchlings, and eggs. Unfortunately, recent studies show that these birds do not become desensitised to the stress of human interaction over time, and that this can negatively impact on the numbers of chicks they reproduce each year.

Image credit: Adélie Penguin P1020537a by Nordsjern. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

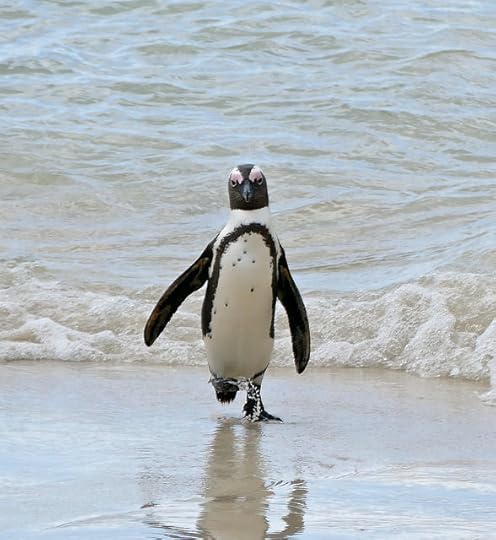

Image credit: Adélie Penguin P1020537a by Nordsjern. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.African penguin

Native to the sun-soaked islands between South Africa and Namibia, the African Penguin is sometimes known by its comical pseudonym, “The Jackass Penguin”, on account of its distinctive, throaty call resembling a braying donkey.

While penguins have colonized every continent of the Southern Hemisphere, today the Jackass Penguin is the only species to grace the shores of the African continent. However, a recent study suggests that before the evolution of archaic humans, African penguin diversity was substantially higher, with fossil records indicating the existence of at least four different species in South Africa.

Today, the modern African Penguin is threatened by near extinction, with around only 70,000 breeding pairs on the planet—less than 10% of the population that existed in 1900. This is caused mostly by human disruption of their coastal habitats, and intensive fishing for schoaling fish like anchovies and sardines, which form the majority of their diet.

Image credit: African Penguin (Spheniscus demersus) by Bernard DUPONT. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: African Penguin (Spheniscus demersus) by Bernard DUPONT. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Galápagos Penguin

As its name suggests, the Galápagos Penguin is the only species found in the rich biodiversity of the Galápagos Islands off the Ecuadorian coast, and the only to even venture north of the equator.

At around 20 inches long, the Galápagos Penguin is one of the smallest members of the bird family. They survive the warmer climate near to the equator by sheltering from sunlight on rocky beaches, and swimming in surrounding waters which are cooled by currents flowing from the southerly reaches of Latin America.

Like many penguin species’, the survival of the Galápagos Penguin is threatened by various human factors: overfishing reducing the availability of their diet; by-catching of penguins in fishing nets; oil spills and other pollutants; and the introduction of dogs, cats and rats to the delicate biodiversity of the Galápagos. As a result, the penguin is an endangered species, and the rarest variety of penguin in the world.

Image credit: galapagos penguins by ollie harridge. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: galapagos penguins by ollie harridge. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Little Blue Penguin

The aptly named Little Blue Penguin is the smallest living penguin species, standing at just 13 inches tall. Sometimes known as the “Fairy Penguin”, the blueish tinge to their feathers is unique amongst all penguin species’.

The non-migratory, nocturnal bird lives in colonies all along Australasian coastlines, remaining close to these homes throughout their lives. Despite their miniature stature, the resilient Little Penguin displays a powerful “site-fidelity”; research shows that they will continue to return to their breeding sites even after human urbanisation. As a result, they sometimes face being hit by jet skis and cars, disorientated by lights, or carried off by dogs in the attempt.

However, their desire to return to these sites shows remarkable ingenuity: in the 1980’s, when a coastal homeowner in Manly Point, Australia built a seawall along the edge of his property, the penguins were found burrowing through a drainage pipe, and even ascending steep stairs—no mean feat for a Little Blue Penguin—to reach their breeding grounds.

Like all animals, the survival of penguins is threatened by human activity. For some, like the Galápagos and African Penguins, this is a particularly imminent threat. But with greater understanding of the immense variations of the penguin family, conservation work stands a greater chance of preserving these remarkable, monochrome birds.

Image credit: Little Penguin (Eudyptula minor) family exiting burrow, Bruny Island, Tasmania, Australia by JJ Harrison. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Little Penguin (Eudyptula minor) family exiting burrow, Bruny Island, Tasmania, Australia by JJ Harrison. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Featured image credit: A pair of African penguins, Boulders Beach, South Africa by Paul Mannix. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Animal of the Month: the lesser known penguins appeared first on OUPblog.

Short History of the Third Reich [timeline]

Historians today continue raising questions about the Third Reich, especially because of the unprecedented nature of its crimes, and the military aggression it unleashed across Europe. Much of the inspiration for the catastrophic regime, lasting a mere twelve years, belongs to Adolf Hitler, a virtual non-entity in political circles before 1914. The timeline below, created from The Oxford Illustrated History of the Third Reich, charts a few key events, focusing particularly on the early foundation years of the Third Reich.

Feature image credit: Cathedral of Light at the Reichsparteitag in Nuremberg, 8. September 1936. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Short History of the Third Reich [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

April 11, 2018

Are you of my kidney?

It is perfectly all right if your answer to the question in the title is “no.” I am not partial. It was not my intention to continue with the origin of organs, but I received a question about the etymology of kidney and decided to answer it, though, as happened with liver (see the post for 21 March 2018), I have no original ideas on this subject.

Most likely, the people who gave kidneys their various names in so many languages had no clue to the function of those paired organs. Nor did their shape inspire them, for otherwise, they would have called kidneys beans. Yet such an idea did not occur to them. Even in Russian, in which the kidney is called pochka, a homonym of pochka “bud,” it is believed that pochka1 and pochka2 are not related. Perhaps the name of the organ pochka has the same root as Russian pechen’ “liver,” that is, pek- ~ pech’ “bake.” But what do the kidneys bake, or who bakes kidneys?

Engl. kidney is even less transparent. The word surfaced in texts only in the 14th century. It must have been preceded by some form like nēore; however, in the early period such a word never turned up, and we don’t know why a neologism superseded it. From late Middle English we have the singular kidnei and the plural kidneiren. The plural is suggestive, for eiren looks like the plural of the word for “egg” (compare Modern German Eiern “eggs”; Modern Engl. egg is a northern form). But what is kidn-? On the other hand, if we divide kid-neiren, everything looks fine at first sight, for Middle Engl. nere “kidney” has been attested.

Kid– poses no problems. Its probable cognates can be found without much difficulty. Cod is perhaps one of them. In Old English, it meant “husk”; today we recognize cod “scrotum,” because it is the first element of codpiece. Old Icelandic koddi meant “cushion,” while Norwegian kodd is both “testicle” and “scrotum.” The same word can rather naturally combine the senses “testicle” and “kidney” (“small glands”?). In close proximity is Old Engl. cwið “womb” (ð = th, as in Modern Engl. this), related to several similar words elsewhere in Germanic, including Gothic, but whether it is akin to cod cannot be decided. Here then is our dilemma: with the division kid-neiren we lose the precious reference to “egg,” while with the division kidn-eiren the tie to nere “kidney” disappears.

This is a codpiece, to protect and advertise. Image credit: Portrait of John Farnham by Steven van Herwijck. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This is a codpiece, to protect and advertise. Image credit: Portrait of John Farnham by Steven van Herwijck. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.According to the usual tentative conclusion, some mixture occurred in Middle English: two words formed a blend. We cannot afford sacrificing nere, because it is a word with easily recognizable congeners all over Germanic. The Modern German for “kidney” is Niere (from nioro). In Icelandic, nýra is akin to it. Only the Icelandic form sheds some dim light on the original meaning of this word, and it does so in a rather unexpected way. Among the Old Scandinavian gods we find Loki and Heimdall (properly Heimdallr). Loki was a mischief-maker, with a shady past (at one time, he must have been feared as a god of death guarding the Underworld: all this is of course a matter of reconstruction), while Heimdall, the possessor of a horn that would announce the end of the world (again death?), is otherwise obscure. In any case, the two were known as traditional antagonists. No full-fledged myth describing Heimdall’s deeds has come down to us, though the disjointed, ill-fitting episodes are numerous.

In a stanza of an old poem, Heimdall and Loki are said to be fighting in seal shape for a hafnýra, that is, haf-nýra. Haf is “sea,” and the object the gods are fighting for is a famous necklace of great value. Apparently, the nýra was made up of (bean-shaped?) gems or pearls. Snorri Sturluson, the great Old Icelandic historian, knew the myth, but he tells us nothing about the shape of the necklace.

This is a reconstruction of the famous hafnýra, an object worth fighting and dying for. A great goddess once slept with four dwarfs to possess it. Image credit: Amulet Freyja (copy of find from Hagebyhöga) by Gunnar Creutz. CC0 1.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

This is a reconstruction of the famous hafnýra, an object worth fighting and dying for. A great goddess once slept with four dwarfs to possess it. Image credit: Amulet Freyja (copy of find from Hagebyhöga) by Gunnar Creutz. CC0 1.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Middle Engl. nere and the forms related to it are akin to Greek nephrós “kidneys” (assuming we can account for the loss of the sound or sounds in the middle), and there are related Latin words, but it would be an exaggeration to say that we are dealing with a common Indo-European name of the kidney. Slavic, as we have seen, went its own way, and the Latin for “kidney” is rēn, the etymon of the corresponding words in the Modern Romance languages (the singular form was rare; usually rēnēs, plural, occurred). Unfortunately, those who have not studied Greek and Latin know many anatomic terms from the names of diseases: nephritis, renal infection, and so forth. It so happens that rēn is one of the most impenetrable Latin words. Nothing at all can be said about its origin. Rēn rhymes with phrēn “heart, mind, etc.” (as in phrenology, schizophrenia, oligophrenia, and others), which I discussed last week (the post for 4 April 2018) in connection with brain, but no conclusions follow from this fact.

When we confront such a situation, the question, naturally, arises: How can a word be so opaque? (Incidentally, a word related to nephrōs did exist in Latin.) I keep returning to this question every time we find ourselves in such an impasse. Although the distant meaning of the nere group is also unknown, we more or less expect the etymology of primordial words to be hidden. But rēn is a common Latin noun, rather than a reconstructed form whose beginnings are lost in prehistory. Once, in passing, I noted that the names of organs are often subject to taboo. Did the Romans decide to avoid the current word and, if so, did they invent a new one to ward off evil spirits? Such fantasies are tempting but fruitless.

Even with Engl. kidney we are on slippery ground. We have no reason to assume that the speakers of Middle English attempted to conceal the word from hostile forces and produced a blend. Why then replace a universally known name with a bulky compound, and why did they play this trick on the name of the kidney? A similar situation recurs again and again. For instance, the history of head is a nightmare. The same holds for bone. Less troublesome but far from simple is the etymology of eye. One can hardly believe that leg is a borrowing from Scandinavian (wasn’t the English word good enough?). Is rēn also a borrowing from some mysterious substrate or a term of witchcraft and sorcery? Words for physical defects (deaf, for instance) pose the same problem.

Kidneys or liver, Sir? —Both! Image credit: Big Brothers Big Sisters Celebrity Waiter by repmobrooks. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Kidneys or liver, Sir? —Both! Image credit: Big Brothers Big Sisters Celebrity Waiter by repmobrooks. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.As noted, our ancestors must have known very little about kidneys. Nowhere do we find a link from kidney to urine. Yet in the 16th century, about two hundred years after the emergence of kidney as an anatomical term, it acquired the sense “nature, temperament”; hence the idiom a man of my kidney. We remember that it was the liver that allegedly regulated emotions. Then why kidney? Etymology is a wonderfully interesting branch of study. The same can be said about medieval anatomy and medicine. Books on this subject are many, and they read like novels. In the original, some of them are among the toughest texts to decipher (horror novels, that is).

Featured image: Which is Loki and which is Heimdall? Image credit: Male Northern Elephant Seals fighting for territory and mates, Piedras Blancas, San Simeon, California (USA) by Mike Baird. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Are you of my kidney? appeared first on OUPblog.

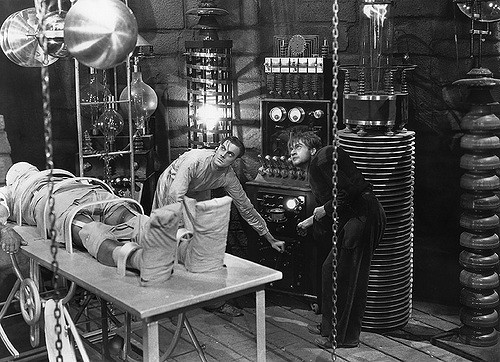

The modern Prometheus: the relevance of Frankenstein 200 years on

This year marks the 200th anniversary of the publication of Frankenstein, Mary Shelley’s acclaimed Gothic novel, written when she was just eighteen. The ghoulish tale of monsters—both human and inhuman—continues to captivate readers around the world, but two centuries after Shelley’s pitiably murderous monster was first brought to life, how does the tale speak to the modern age?

The answer is that the story remains strikingly relevant to a contemporary readership, through its exploration of scientific advancements and artificial intelligence.

Frankenstein has been described by many readers as the first work of science fiction. The titular Victor Frankenstein harnesses a mixture of alchemy, chemistry, and mathematics to gain an unprecedented insight into the secrets of animating sentient flesh. The green, metal-bolted creation of popular culture is a far cry from Shelley’s literary monster, whose translucent yellow skin and black lips are compared to the desiccated flesh of a mummy. The creature instantly repulses all who set eyes on him, including his creator.

Victor’s insatiable desire to complete his scientific feat are, like his creature, both captivating and repulsive. The monster is the product of his all-consuming need to gain the power of a god and conquer the laws of nature. When the process is complete, he is instantly horrified by the result of his efforts, but with the monster-genie out the bottle he cannot control the creature or prevent it from destroying all he holds dear.

The process reflects a mistrust of scientific discovery, which was commonplace in the works of the Romantics. From its beginnings, The Romantic Movement was concerned with regulating the unchecked pursuit of scientific or technological advancements via “natural philosophy,” or the sciences—a potential that was prized above all else by the Enlightenment.

Romanticism, whilst recognising the exciting potential of science, valued the importance of the natural order. In the generation who saw unprecedented technological feats, including the invention of the steam engine and indoor plumbing, this must have seemed a particularly pertinent issue to a young Shelley. The novelist conceived her literary creation in what she described as a “waking dream,” which she feverishly wrote during a summer spent holidaying with her husband in the home of Lord Byron.

Image credit: Frontispiece to Mary Shelley, Frankenstein published by Colburn and Bentley, London 1831 Steel engraving in book 93 x 71 mm by Theodor von Holst. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Frontispiece to Mary Shelley, Frankenstein published by Colburn and Bentley, London 1831 Steel engraving in book 93 x 71 mm by Theodor von Holst. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The combination of her interaction with these two prominent Romantics, and the vast scientific advancements of her generation, resulted in more of a “waking nightmare.” The tale, like contemporary fears of what mechanical developments could bring, was frightening. Both Frankenstein and his monster embody the dangers of unchecked scientific discovery, and the resulting destruction is a parable for regulating these advancements.

But the monster is more than just a hideous deformity: through secretly observing human interaction, he comes to understand language, to decipher writing, and to appreciatively read the works Paradise Lost, Plutarch’s Lives, and The Sorrows of Young Werther. By the time he is reunited with his maker, he passionately and eloquently expresses his desire to be accepted by another living soul, either human or of Frankenstein’s own making.

Shelley’s novel doesn’t present scientific and technological advancements as purely monstrous. Rather, it is the callousness of the creator, who cannot or will not anticipate the dangers of their invention, who is truly monstrous. Throughout the novel, the reader is invited to bear witness to this ironic parallel.

In the modern age of IVF and genetic engineering, Frankenstein’s alchemic studies and chemical apparatus are charmingly outdated as a means of generating life. But the pursuit of technical discovery, and the dangers this poses to the natural order, finds easy parallels in modern technological advancements, particularly surrounding artificial intelligence.

The modern day is fraught with fears of the implications of machine learning—both what it can create, and what this will mean for mankind’s global future. The 20th and 21st centuries have seen a proliferation of literature on this theme, including Phillip K. Dicks’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, Ridley Scott’s Terminator series, and Alex Garland’s Ex Machina. All these artistic works find their roots in the themes of Shelley’s 200-year-old novel: a “monster” of mankind’s own making.

Image credit: Colin Clive & Dwight Frye in “Frankenstein”, 1931 by Insomnia Cured Here. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Colin Clive & Dwight Frye in “Frankenstein”, 1931 by Insomnia Cured Here. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Shelley gave her novel the subheading “The modern Prometheus.” The Classical Titan, who stole fire from the gods and gifted it to man, was tortured eternally for his crimes. In a parallel fable, the prodigious Victor Frankenstein places the spark of life into a creature which he does not know how to control. The brilliance of his achievement is undeniable, but the unchecked flame eventually consumes his loved ones, himself, and even his creation. Like Prometheus, Frankenstein steals a gift from the realm of gods, which he cannot wield and is sorely punished for.

In the age of complex machine learning, Shelley’s reimagined Prometheus has never been more modern than he is today. As the lately departed Stephen Hawking stated when opening the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence:

“Success in creating AI could be the biggest event in the history of our civilisation. But it could also be the last—unless we learn how to avoid the risks.”

Featured image credit: Eery by maraisea. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post The modern Prometheus: the relevance of Frankenstein 200 years on appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers