Oxford University Press's Blog, page 260

April 24, 2018

From early photography to the Instagram age

In our contemporary moment, as our digital spaces are saturated with feeds and streams of images, it’s clearer than ever that photography is a medium poised between arresting singularity and ambiguous plurality. Art historians have conventionally focused on the singularity of the photograph and its instant of capture. But the digital turn has prompted many scholars—myself included—to reconsider photography in its many serialized incarnations.

Whether for artistic or scientific purposes, the photograph has always been enrolled in larger bodies of imagery. In the nineteenth century, for instance, families collaged together portraits of loved ones and famous figures in private albums. Meanwhile, the French criminologist Alphonse Bertillon pioneered the collation of police mugshots into vast archives, and inventors such as Eadweard Muybridge used chronophotography to trace the contours of human movement.

Image credit: Sitting down on chair and opening fan, ca. 1884–1887. By Eadweard J. Muybridge, From the series Animal Locomotion. Collotype. George Eastman Museum, gift of Ansco. Reproduced with permission from the George Eastman Museum.

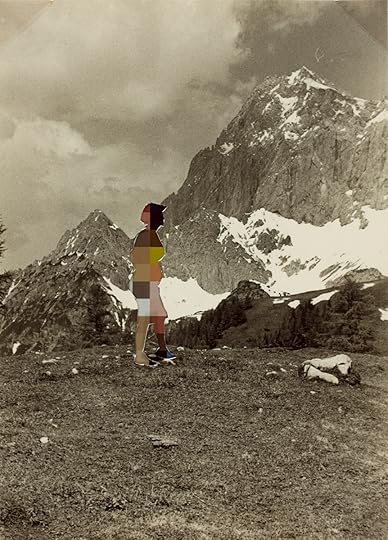

Image credit: Zeitreisende: f1vbg23ock.jpg, 2012. By Lilly Lulay. Photocollage (gelatin silver print and inkjet print). George Eastman Museum, gift of Joseph Cunningham in honor of Lisa Hostetler. Reproduced courtesy of the George Eastman Museum.

Image credit: Zeitreisende: f1vbg23ock.jpg, 2012. By Lilly Lulay. Photocollage (gelatin silver print and inkjet print). George Eastman Museum, gift of Joseph Cunningham in honor of Lisa Hostetler. Reproduced courtesy of the George Eastman Museum.Such practices only increased in the twentieth century, with the growth of mass media photography. In 1927, the cultural critic Siegfried Kracauer described his age in ways that speak uncannily to our own: “The world has taken on a photographic face,” he wrote. Everyday life was now subsumed beneath a “blizzard of photographs.”

Kracauer was worried that the visual culture of modern had (paradoxically) hidden the world from us. For him, the blizzard of photographs clouds our view, preventing us from seeing the social and historical realities behind the world’s photographic face.

Something of this same concern shapes Zeitreisende, a 2012 photographic series by Lilly Lulay that considers how modern-day hypervisibility can mean anonymity, an evacuation of human individuality and specificity. Zeitreisende means time traveler, and Lulay’s series envisages the modern woman as a pixelated figure making scenic pit stops along the feeds of contemporary media.

Lulay’s photographs parody the vacation shots we share on social media: the evidence of the self in specific temporal and geographical locations. But vacation shots, like Lulay’s traveling women, sit uneasily in time and space. They tell our friends and followers, “I am here” or “I am there”—but also, as the present tense of the photograph slips seamlessly into the past, “I was here,” “I was there.”

Lulay’s time travelers are anonymous and unidentifiable; they are assembled in and as visual data. What happens to the individual, Lulay seems to ask, in a world in which all private selves face, or might face, a mass audience? If nothing is private, can anyone really be individual?

In repurposing found photographs, Lulay draws from and works against the overproduction of images in our time. She also responds to the age of memes and selfies, in which the individual photograph is inserted into endless Instagram and Facebook feeds. In these guises—as with the many serialized forms of photography from the earliest days of the medium—the individual photograph comes to look less individual, less isolated than we might imagine it to be. It comes to look like a time traveler, always shifting from one sequenced context to another. Image credit: Zeitreisende: f0po1ab5gr9w.jpg, 2012. By Lilly Lulay. Photocollage (gelatin silver print and inkjet print). Reproduced courtesy of Lilly Lulay.

Image credit: Zeitreisende: f0po1ab5gr9w.jpg, 2012. By Lilly Lulay. Photocollage (gelatin silver print and inkjet print). Reproduced courtesy of Lilly Lulay.

Picturing women in postdigital space

To some extent, Lulay’s images can be seen to represent a common complaint about the image culture of the internet age: that it saps meaning and flattens individual difference, producing slick, superficial visions of too-perfect lives.

Perhaps the exemplar of this phenomenon is the Instagram influencer, usually, a young, thin, white woman employed by advertisers to hawk fashion or other products online—but always with a mask of authenticity, the crucial currency in the social media economy. The Instagram influencer—along with all selfie-snapping millennials—is the object of much of our culture’s anxieties about Internet-age narcissism and homogeneity.

Indeed, there’s no doubt that social media provides a context for the assertion and maintenance of gendered social norms. It’s hardly a coincidence that Instagram influencers tend to replicate the same conventionalized standards of beauty that Naomi Wolf railed against in The Beauty Myth almost thirty years ago.

Yet, scholarly literature on selfie culture is divided. Selfies are recognized as a mechanism of social control, one that reproduces the objectification of women’s bodies in the history of art and of popular culture. But selfie culture can also be seen to support empowering acts of self-expression, as is evident in #MyStory, a campaign launched a few years ago to expand the range of representations of women on Instagram.

Image credit: African American woman wearing white gloves, ca. 1855. By Unidentified maker. Daguerreotype with applied color. George Eastman Museum, gift of Eaton Lothrop. Reproduced courtesy of the George Eastman Museum.

Image credit: African American woman wearing white gloves, ca. 1855. By Unidentified maker. Daguerreotype with applied color. George Eastman Museum, gift of Eaton Lothrop. Reproduced courtesy of the George Eastman Museum.The long history of women in photography

Social media pushes us to exist in the moment; through its time stamps and reverse chronological design, it accelerates away from a sense of history or context. As our feeds constantly refresh with new content, we’re moored in a perpetual present of smashed-avocado brunches, fitsperational bodies, and cat videos.

But throughout the history of the photographic medium, the photograph in sequence—in predigital feeds, as it were—has not only served to occlude the underlying power structures of culture and society, as Kracauer once claimed. It has also served to unveil those structures.

For example, the growing archive of portrait photography in the nineteenth century made it possible to identify, in newly precise ways, the delimiting and codifying of femininity and masculinity as a series of visual cues connected to fashion, gesture, and gait. Apprehended as a tradition and a genre, portrait photography reveals how ideas about gender emerge through shifting social conventions.

So, in a new digital project, I’m using Instagram to test how this serialized medium might be used to create, not diminish, a sense of history in relation to representations of women. “Object Women” seeks to give a complex backstory to both high art representations, as in Lulay’s photography, and the vernacular self-portrayals published by women every minute on social media.

Just as Instagram functions simultaneously as a means for objectifying women and as a site for resisting objectification, so too the longer history of women under the camera’s gaze is configured through these two competing impulses. If depictions of women have long been central to photography’s feeds and streams, then postdigital platforms offer a unique opportunity to uncover how these depictions have—and haven’t—turned women into objects of sight.

Featured image credit: “Iphone photo” by Dariusz Sankowski. CC0 Creative Commons via Pixabay.

The post From early photography to the Instagram age appeared first on OUPblog.

WANTED: An alternative to Competency-Based Medical Education

Nicaragua (1984): In a hospital—or at least what was labelled as a hospital—a physician receives an elderly woman in a hypertensive crises. He administers the only anti-hypertensive medication available—Reserpine—a drug that is now rarely used because of its side effects. To his profound dismay the patient suffers a stroke and dies a few hours later. There are no morgues in such rural hospitals. There are no ‘funeral parlours’ in the villages. Families take their departed loved ones home for burial. In this instance, the family, owners of a pick-up truck, considers returning home with their mother in the back of the truck, laid out alongside bags of fertilizer. In a flash, they recognize it to be undignified: “Mom, after all, was still warm!” So, with the assistance and blessing of the physician they prop mother up in the cabin and off they drive! A dusty and dilapidated red Ford pick-up, with a cadaver sitting in the passenger seat, is seen making its way through vast expanses of sugar canes.

I was that physician in 1984. The events I describe above do not capture the dilemmas nor reflect the contexts in which the majority of medical practitioners work today, most assuredly not in resource-rich nations. However, all too familiar are such flashes of human dramas and plights, accompanied by an uncertainty, at times crippling, due to an inevitable lack of clear, tested, and validated scripts to guide the behaviours of patients, families, and doctors.

One of the obligations of medical schools is to graduate doctors who will be able to make humane and compassionate decisions—competently—within a framework of scientific knowledge. It is useful to dissect the claims expressed in this sentence.

With respect to “humanness and compassion:” whilst undeniably an enduring aspiration, medicine has not always been up to scratch and there are times in history when this core expectation has needed highlighting. This occurred, for example, in 1803 when Thomas Percival crafted a code—the first modern one—of medical ethics. A contemporary incarnation of guidelines for good ethical conduct has been the emphasis on professionalism.

Image credit: Image courtesy of the Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University. Do not reproduce without permission.

Image credit: Image courtesy of the Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University. Do not reproduce without permission.With respect to science: scientific methodologies became prominent in the discourses of medicine as well as medical education following WWII. This has culminated, spectacularly, in the munificence of numerous medical research establishments and the influential evidence-based medicine (EBM) movement. EBM has been a driver of medicine’s institutional functions and structures for the past 30 years. Few would question the importance of evidence, science, and objectivity, even though many have argued that scientism needs to be tempered and humanism given greater pride of place in the medical act.

What about the word “competently” in the middle of that sentence: What does it mean? Is this qualifier all “to the good”? Clearly, no one would want an incompetent doctor. However, the issue has been confused recently by the arrival of the term “competency.” The relationship of competency and competencies to competence and competent is under scrutiny. Many opinion leaders, although thankfully not all, subscribe to a framework called “Competency-Based Medical Education” (CBME) believing that it will ensure safe and competent doctors.

CBME is founded on the premise that identification of the key tasks or steps of a specific professional role or activity will permit educators to assess and certify learners on their mastery of that unit of work. The activity can be referred to as a competency. Competency is etymologically linked to competence but should not be conflated with competence.

The CBME approach revolves around the notion that a competency must be specified in behaviourally measureable terms. Achieving this is possible for some important medical activities, particularly for procedural or manual tasks. But, it is impossible for many clinical decisions and acts. One cannot provide a template for curious, creative, and courageous professional responses. One cannot reliably measure empathy, resilience, or the tolerance of uncertainty. One cannot prepare a student for every contingency—to know that a clinical situation requires entering a patient’s room with a light and easy step and reassuring smile rather than a deliberate gait and a questioning facial expression. As my brief anecdote demonstrates, medicine is not a rote activity and doctors cannot be reduced to assemblages of competencies—the implication in CBME. It would be unfair to consider CBME as ignis fatuus. It will surely make a useful contribution but it holds a potential to distract and misdirect. Viable alternatives are needed to guide and, critically important, to inspire medical educators. One is available.

The preeminent physician of the 20th century was William Osler. Osler is widely regarded as the complete physician. It is not widely known that he described an approach to pedagogy; he called it “the natural method for teaching medicine.” The natural method was an apprenticeship grounded in patient care. For Osler, the patient was the most important and precious source of knowledge for physicians and physicians-to-be. I am confident that Osler would have understood the importance of the doctor acting as a facilitator and counsellor for that Nicaraguan family.

Osler’s natural method needs to be re-examined, repurposed, and reimagined in the light of current day challenges. It can continue to serve contemporary medical schools and is ideally suited to provide a conceptual anchor for an authentic physicianship, by which I am referring to the attributes of physicians needed to fulfil the roles of the healer and professional.

Featured image credit: Find your path by Bobby Stevenson. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post WANTED: An alternative to Competency-Based Medical Education appeared first on OUPblog.

April 23, 2018

How will Billy Graham be remembered?

Billy Graham’s death on 21 February, 2018, unleashed a flood of commentary on his life and legacy, much of it positive, some of it sharply negative. Both the length of his career and the historical moment at which he died contributed to the complexity of this discussion.

If his life had ended a decade ago, praise would likely have dominated his obituaries. He ranked in the top 10 on the USA Today/Gallup list of Most Admired Men almost every year since the poll began in 1948. Generations of Americans regarded him as “America’s Pastor,” a unifying figure who befriended presidents from Dwight Eisenhower to Barack Obama, and who soothed the nation’s soul after crises such as the September 11 terrorist attacks. Graham’s fans included the millions who attended his evangelistic crusades and the millions more who watched them on TV. Perhaps they tuned into his long-running radio show Hour of Decision, took advice from his “My Answer” newspaper column, or read his bestselling books, from the runaway hit Angels: God’s Secret Agents (1975) to his last, The Reason for My Hope (2013). (A later book, Where I Am: Heaven, Eternity, and Our Life Beyond, almost certainly was not written by Graham himself). Positive press coverage burnished this image of the perpetually beloved preacher, as Graham and his team cultivated cordial relationships with reporters while avoiding the tawdry scandals that tripped up so many other revivalists.

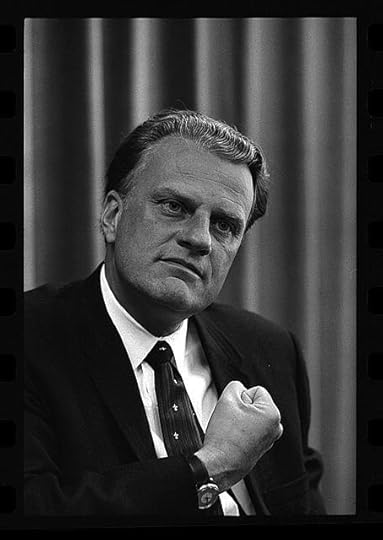

Billy Graham by Warren K. Leffler. Public Domain via the Library of Congress.

Billy Graham by Warren K. Leffler. Public Domain via the Library of Congress.Scholarship published in recent years has told more complicated narratives about the revered evangelist. For example, Darren Dochuk described Graham’s “middle-of-the-road average” approach to racial integration, which led him to partner with oilmen rather than Civil Rights activists. David King made a similar observation about Graham’s hesitant embrace of anti-poverty initiatives. Seth Dowland touched on ways that Graham’s model of evangelical manhood marginalized women. The specter of Graham’s alliance with Richard Nixon haunts many accounts of the evangelist’s career.

The fact that 81% of white evangelical Christians voted for Donald Trump has led many scholars in 2018 to turn an even more critical eye on Graham. Causes that Graham held at arms’ length (Civil Rights, welfare programs, and gender equality) were more vocally repudiated by Trump. Meanwhile, evangelical leaders in 2016 eagerly embraced the Republican candidate, something Graham had vowed not to do after Watergate. Was it Graham’s legacy to leave behind a religious tradition that amplified his flaws? Did the election prove that he had been “on the wrong side of history” all along, as Matthew Avery Sutton argued in The Guardian? Or did the rise of Trump-supporting “court evangelicals,” among them Graham’s son Franklin, mark a turn away from Graham’s essential moderation, winsomeness, and chastened patriotism? If Graham had not been sidelined by illness, could the last decade of American religion and politics have played out differently?

Graham was nearly 100 years old when he died. His views on many subjects, including nuclear proliferation, the environment, global humanitarianism, and women’s ordination, changed over time. Assessments of Graham over the next 100 years will evolve as well, as we move from our current, intensely polarized moment into eras that none of us can predict.

Featured Image credit: Billy Graham by National Archives of Norway. CC-BY-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post How will Billy Graham be remembered? appeared first on OUPblog.

The choppy waters of beach ownership: a case study

Martins Beach is a spectacular stretch of coastline south of Half Moon Bay in San Mateo County, California. It is a well-known fishing spot, a family picnic destination, and a very popular surfing venue. For nearly a century, the owners of the beach allowed visitors routinely to access the beach using the only available road. In 2008, billionaire Vinod Khosla bought Martins Beach and the surrounding property. After two years of complying with the county’s request to maintain access to the beach, Khosla permanently blocked public access. A California environmental organization filed suit against the property owner. In 2017, a California appellate court ruled in their favor, holding that a property owner cannot block access to the beach without permission from the California Coastal Commission, which exercises regulatory oversight over land use and public access in the California coastal zone. The court ruled that barring access constituted development, requiring a permit which Khosla failed to obtain.

The case is another instance of a conflict between beach owners and the public that has played out around the country. Beach owners rely on private ownership to assert their right to exclude the public, and members of the public claim a right to access and use the beach for recreation. The Martins Beach controversy was decided on the basis of California regulatory law, but elsewhere courts have relied on broader principles such as the public trust to decide that beach owners must allow “reasonable access” to and use of not only the wet sand area but also the dry sand portion of the beach.

Beach owners rely on private ownership to assert their right to exclude the public, and members of the public claim a right to access and use the beach for recreation.

Beach access is a contentious issue, partly because it so starkly poses the question just how broad the owner’s right to exclude is. The old adage that a man’s home is his castle may be true of a personal residence, but is it true of a private beach as well? At the other end of the spectrum from the right to exclude lies property that is subject to a right of access by the public in general, what in Roman law was called res publicae. Today the public’s right to use the beach for purposes including recreation extends to the wet-sand portion. Public right of access to the dry-sand portion of private beaches is the major point of contention in cases like Martins Beach and elsewhere.

The moral foundation of private property is human flourishing, and that good should define the scope of an owner’s right to exclude. Human flourishing requires that we develop certain capabilities, including health, autonomy, practical reasoning, and so on. The communities to which we belong help us develop these capabilities, so we owe ourselves obligations to help those communities themselves flourish. In the beach context this may require owners to permit public access across their beach. Recreation is not a luxury; it is a necessity. The contributions of recreation to physical and mental health are well-known, and access to means of recreation is essential. Recreation also provides a means for cultivating sociability, learning how to live with others, including strangers. Here, again, the beach is an important locus of capability development.

Of course, the owner’s essential capabilities of personal security and privacy may also be at stake. So, if the beach owner’s primary residence is a home on the beach, and public beach access would materially jeopardize the resident’s security or privacy, then other locations for public access should be found. Apparently that was not the case in Martins Beach, however.

By focusing on the capabilities at stake, this human flourishing theory provides a more morally satisfying analysis of property disputes such as access to beaches.

Featured image credit: sand by jahcordova. CC0 via pixabay .

The post The choppy waters of beach ownership: a case study appeared first on OUPblog.

April 22, 2018

Earth Day 2018: ending pollution [quiz]

Happy Earth Day! Celebrated across the world, this day was created to help raise awareness and encourage action around environmental protection. This year’s Earth Day focus is on ending plastic pollution. Plastic pollution is threatening the survival of our planet, and is especially harmful within marine environments. While litter is an ongoing issue in our oceans, marine litter is dominated by plastic items, and in 2010, it’s estimated that 4,8000,000-12,700,000 tonnes of plastic were released into the oceans. Plastic items are especially harmful to marine environments since they can take years to break-down once in the ecosystem. Curious to see just how many years plastic and non-plastic pollutants are estimated to break down in our oceans? Take our quiz to find out and learn how you can help reduce the amount of plastic litter in our oceans.

Featured image credit: Earth Planet World Globe Space Map Of The World by PIRO4D. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Earth Day 2018: ending pollution [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

The international community struggles to end civil wars. How can international organizations help?

At the recent Kuwait International Conference on Reconstruction of Iraq, countries and international organizations pledged US$30 billion to reconstruct Iraq after years of war. This number fell short of the US$80 billion estimated necessary by the Iraqi government as needed to rebuild the country. Iraq is only one example of the lasting damages caused by civil wars. Yet, international responses often seem more concerted after civil wars have ended, rather than during their initial phases.

Other current wars illustrate this unfortunate pattern. As of March 2018, the civil war in Syria has likely claimed over 500,000 lives and created severe and lasting damages to public health systems. Yemen has entered another year of large-scale violence, with little prospect for quick resolution, as a recent report documents. Violent armed conflicts elsewhere in the world have equally devastating consequences. Despite these dramatic developments, the international community faces a massive challenge of how to respond to emerging political violence in a decisive and effective manner.

Ample research documents the difficulties of ending violence once it starts. The UN engages in preventive diplomacy in some cases, but not in all violent conflicts. There is also evidence that UN peacekeepers can reduce casualties both among civilians and on the battlefield and can also reduce the risk of civil wars recurring once they have ended. Yet, new research suggests that the duration of civil wars has increased, with considerable human cost. Slow and ambiguous international responses to political violence have emboldened governments and rebels to use force to push for their demands. A lack of lasting engagement by external actors is often part of the explanation for why these conflicts continue to rage.

There are reasons for a more optimistic view of how the international community can help prevent civil wars in the first place, though. A specific subset of intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) that has the capacity and self-interest to engage in member states in a way that directly addresses commitment problems in pre-civil war bargaining. These highly structured IGOs include institutions such as the World Bank, Inter-American Development Bank, or the Economic Community of West African States. As multilateral bodies, these organizations have clearly defined, and often economic, mandates. While mediating political disputes lies beyond their mandates, civil wars in member countries would impede these organizations’ ability to carry out their tasks. This functional self-interest gives these organizations a powerful tool to establish incentives to avoid political violence in member countries.

This leverage of highly structured IGOs in member countries has a notable influence on the costs and benefits that governments and rebels face in early phases of political unrest and violence, before civil wars escalate. When highly structured IGOs are engaged in a country, both governments and rebels can expect clear costs from escalating violence: it will lead to a disengagement of highly structured IGOs and withdrawal of their staff, resources, and other benefits. Yet, highly structured IGOs also carry the promise of rewards for keeping the peace by providing substantial resources and benefits conditional on the absence of further violence.

Conflicts in countries with more connections to highly structured IGOs faced a considerably lower risk of escalation.

This puts highly structured IGOs into a unique position to credibly condition benefits on conflict prevention. Their self-interest in successful institutional performance requires them to avoid engagement in contexts of high fragility and violence. This means that when highly structured IGOs are engaged in a country, governments and rebels in pre-civil war bargaining are acutely aware of the high material costs of violence. In turn, this provides a crucial commitment device to settle conflicts before they escalate.

The evidence suggests that the engagement of highly structured IGOs in member countries is associated with a substantial decline of the risk that political conflicts escalate to civil wars. Since World War II, roughly one-third of more than 260 separate low-level armed conflicts have escalated to civil war. But conflicts in countries with more connections to highly structured IGOs faced a considerably lower risk of escalation, reduced by up to a half.

Representative of these broader trends, the history of East Timor illustrates how international organizations can successfully incentivize conflict parties to negotiate and resolve political disputes before they escalate. In Indonesia, a crisis originated when the East Timorese opposition demanded independence in the late 1990s. After an initially violent response of the Indonesian government, highly structured IGOs, most notably the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, threatened and imposed sanctions on the regime. The regime responded by yielding to the pressure from these IGOs and calls for East Timor’s independence. Both sides reached a settlement and avoided a full-scale civil war. As promised, highly structured IGOs then resumed old and begun new programs. Both Indonesia and East Timor have since made notable economic improvements, partially helped by resources coming from highly structured IGOs.

As a counterexample, highly structured IGOs did not have much leverage to set similar incentives for the conflict parties in Syria in 2011. In this case, the Syrian government was comparatively isolated from the international community, including highly structured IGOs. Without their leverage, there was little the international community could do to effectively curtail the government’s response to the opposition. Instead, the regime went on a major offensive. Seeing this, the opposition turned to defending itself and grew into a rebel force. Without much influence to resolve commitment problems, other international efforts to mediate and end the civil war have failed.

Studying the role of highly structured IGOs and the incentives they bring to political disputes in member states suggests one way through which international organizations can help limit the dramatic costs of violent conflicts, such as those in Syria and Yemen. Similar IGOs also can play a role in helping resolve disputes between countries. These IGOs have increasingly emphasized concerns about the detrimental impact of violence on their missions, as the examples of the World Bank, Inter-American Development Bank, and the Economic Community of West African States show. Coordinating these efforts may provide the international community with an additional effective conflict resolution tool.

Featured image credit: United Nations by xlibber. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr .

The post The international community struggles to end civil wars. How can international organizations help? appeared first on OUPblog.

Sustainable libraries: a community effort

Sustainability in the 21st century takes various—often inventive—forms. Several industries are making changes to the physical structures of their business in order to be more environmentally conscious. One such industry is quickly becoming a global leader in this initiative: libraries.

Some libraries are constructed entirely from recycled materials, such as the Microlibrary Bima in Indonesia, built with upcycled, used ice cream buckets. Others fit into the landscape itself, like the TU Delft Library in the Netherlands, almost vanishing into the lush greenery surrounding it. Many libraries work diligently to design LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certified environmentally sustainable spaces that not only use the renewable resources found in abundance around them, but also reflect the beauty and grandeur of the local landscape.

One such library that successfully pairs function and sustainability is the Vancouver Community Library in Vancouver, Washington. “Libraries for the last 10 or 20 years have been reinventing themselves to stay relevant in today’s communities”, says Jackie Spurlock, Branch Manager of the Vancouver Community Library. “This reinvention involves embedding ourselves in our communities and working with the community on its priorities and aspirations.”

One such aspiration of the community of Vancouver, Washington was to design a space where education, research, and leisure can flourish in harmony with the environment. Thus the idea for the Vancouver Community Library was born. The building opened on 17 July 2011, welcoming patrons to walk on the reclaimed walnut wood floors in the Vancouver Room, to read a book on the fifth floor terrace where the green roof captures and absorbs storm water, reducing run off, and to bask in the daylight streaming through the large glass windows.

“Deck” courtesy of the Vancouver Community Library. Used with permission.

“Deck” courtesy of the Vancouver Community Library. Used with permission.The library contains a long list of environmentally sustainable features, such as the raised access floor system. The plenum space created by this raised floor houses much of the wiring, plumbing, and network cabling used throughout most of the building, and enables easy access to the systems below, which cuts down on maintenance costs and provides for future flexibility should changes need to be made. Faucets and toilets in the bathrooms are hands-free, and low flow water saving fixtures powered by sensors that harvest the room’s existing light eliminate the need for electrical power. Over 20% of the materials used in the building contain recycled content. One of the most impressive features, however, has to be the daylighting.

“The daylighting is the most beneficial, most impactful part of building to both employees and patrons of the library”, explains Marla Young, Executive Assistant of the Vancouver Community Library. “Not only is it just a visually stunning architectural feature, but it also contributes to the wellbeing of the patrons and staff. Studies have shown that productivity is much higher in buildings with daylight views, there is higher employee retention, and employees take fewer sick days.”

Making the library a sustainable space and becoming LEED gold certified while doing so, however, is no easy task. Young explains that maintaining an environmentally sustainable building is often “more labor intensive and more expensive” than buildings that are not LEED certified, and the building team hit a few snags along the way. The cork floors in the Community Meeting Room are a renewable resource—cork being a bark that grows naturally on trees and is harvested without killing or damaging the existing tree—but the material is less durable than other non-renewable resources.

“It is a beautiful material and helps to maintain the sound control of the room”, says Young, “but it turned out to be a very soft product, so it’s been damaged in the years that it’s been installed.” Still, Young believes the positives of an environmentally sustainable building far outweigh the downsides.

“Exterior of the Vancouver Community Library” courtesy of the Vancouver Community Library. Used with permission.

“Exterior of the Vancouver Community Library” courtesy of the Vancouver Community Library. Used with permission.“It is more complicated to operate the building and to keep the green features compliant with certification”, says Young, “but the building’s longevity is classified as having a life span of 75-100 years.”

Despite any challenges, the community still sees the library as a vital part of their neighborhood, and worth the time and money spent to create it.

“I give tours of the building, and the one thing that always surprises me,” says Young, “is that the members of the community who are touring appreciate that we are good stewards not only of the environment, but also of their tax dollars.”

With an average of 1,500 people visiting the library daily, it is clear that the community is proud of the building and enjoys the benefits of the services it has to offer.

Much of the programming occurring within the library originates from the desires of the community members. The library staff has created maker spaces for patrons to experiment with technology, has spearheaded civic engagement programs where people come together to talk about issues pertaining to the community, and has started an early learning center for children to prepare them for school.

“The environmentally sustainable design of this building is the reflection of the consciousness of the community,” says Young. “Their input was key in its creation and maintaining this is a reflection of the community and the priorities they hold.”

The libraries of today are working to be a resource for both the patrons and the environment in which they live, serving patrons in many aspects of their lives, and preparing them for a successful and sustainable future.

Featured image credit: hands world map global earth by stokpic. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Sustainable libraries: a community effort appeared first on OUPblog.

April 21, 2018

The promising strategy of rewilding

Since the 1950s there has been dramatic increase in threats to the world’s plants and wildlife. Scientists around the world agree that we are in the midst of the sixth mass extinction. In response, numerous laws have been enacted—like the US Endangered Species Act of 1973—in order to halt or slow down this rate of extinction. Scientists and conservationists have teamed up and developed new methods in the field of conservation biology to combat this issue.

But what are these methods? How do they work? Below, we explore these questions and consider the paths ahead.

The sixth mass extinction

In the 20th century in North America, there were significant amounts of forest regeneration due to the abandonment of marginal farm land and monumental legal strides made by the environmental movements of the 1960s and 70s. Even though there now exists legal protection for threatened species and their habitats, we are still experiencing what is considered to be the greatest mass extinction of species since the extinction of dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

Despite the progress made by conservation initiatives, scientists report that most recovering species have not yet reached the level that would ensure self-sustaining populations. Reports show that the population sizes of vertebrate species have dropped by almost 60% in little more than 40 years, and are likely to reach 67% by the end of the decade. Effective action must be taken before it’s too late.

What is the cause?

While it is common to think that the current extinction crisis began in the Age of Discovery, it in fact started ca. 13,000 BP. And despite not being able to pinpoint one exact cause, current research has focused on two predominant sources: climate change and human endeavors. One of the hypotheses currently being tested is known as the Anthropocene, the notion that humans have significantly impacted the environment. It is hardly contested, though, that human inventions, such as aerosol, have affected the Earth’s climate.

What can be done

Since World War II, steps have been taken to pass significant laws in order to change our course. Zoos—once thought of as menageries of wild animals and entertainment for families—have transformed into programs that focus on conservation breeding. Nevertheless, zoos have limited space. Even if they dedicated half their space to conservation programs, they still would not be able to accommodate more than 800 of the 7,000+ threatened species of vertebrates.

Rewilding has been hailed as the most exciting and promising conservation strategy. Rewilding aims at maintaining or even increasing biodiversity through the restoration of ecological and evolutionary processes using extant keystone species or ecological replacements of extinct keystone species that drive these processes. Whereas traditional restoration typically focuses on the recovery of plants communities, rewilding focuses on animals, particularly large carnivores and large herbivores. Moreover, restoration tries to return an ecosystem back to some previous condition, rewilding is forward-looking: rewilders learn from the past how to activate and maintain the natural processes that are crucial for biodiversity conservation. Rewilding implements a variety of techniques to re-establish these natural processes.

Besides the familiar method of reintroducing animals in areas where populations have decreased dramatically or even gone extinct, rewilders also employ some more controversial methods. Back breeding aims at restoring wild traits in domesticated species. Taxon substitution replaces extinct species by closely related species with similar roles within an ecosystem. De-extinction attempts to bring extinct species back to life again using advanced biotechnological technologies such as cloning and gene editing.

Considerations

There is not a universal consensus on what the best method for rewilding is. Although rewilding has good intentions, there are economic, ecological, and even ethical concerns. The acquisition of land, the translocation and monitoring of animals, and the fencing of large areas will require considerable financial resources. It is feared that, given these high costs, in combination with the comparatively high salaries of North American managers and scientists, attention and funding will be diverted from more traditional conservation strategies in Asia and Africa. Some methods, such as the de-extinction project and taxon substitution, have raised many ethical questions. What happens if these new species wreak havoc on our environment? Shouldn’t we be spending our resources on extant endangered species?

As ambitious as the scope of the project is, rewilding represents a positive shift in conservation strategy. Rather than passively protecting and conserving existing nature reserves, it aims at creating new, rich landscapes that support wildlife.

Featured image credit: 1 Elephant beside on Baby elephant by Pixabay. Public Domain via Pexels.

The post The promising strategy of rewilding appeared first on OUPblog.

April 20, 2018

What can brain research offer people who stutter?

There’s something compelling about watching a person who stutters find a way to experience fluent speech. British TV viewers witnessed such a moment on Educating Yorkshire, back in 2013. When teenager Musharaf Asghar listened to music through headphones during preparations for a speaking exam, he found that his words began to flow. Singers, like Mark Asari who is currently competing on The Voice UK, also demonstrate how using the voice in song, rather than speech, can result in striking fluency.

In fact, a range of techniques can temporarily enhance how fluently a person who stutters can speak. Changing auditory feedback by delaying it, or “drowning” it out with music, or altering habitual speaking patterns by singing, or speaking in time with a metronome, often results in an immediate increase in fluency. However, the effect disappears as soon these alterations are removed. Although the underlying mechanism isn’t completely understood, these effects indicate that people who stutter may show brain differences in how the signals guiding speech movements are integrated with feedback on the sound and feel of speech.

Brain imaging studies of adults who stutter do reveal differences in both the structure and the function of the circuits involved in speech production. For example, a number of studies show that the bundle of nerve fibers connecting the sensory and motor brain areas involved in speech production is less organized in people who stutter. This could affect communication between these brain areas, causing speech disfluency. There are also differences in the patterns of brain activity we see when people who stutter speak in the MRI scanner. An area in the left frontal part of the brain – an important hub in the circuit that plans and executes speech – is less active in people who stutter than in people who don’t. The equivalent area on the right side is often more active in people who stutter. We think this pattern of increased activity on the right could make up for the lack of activity on the left, but it might also reflect the stuttering process itself.

So, how can information about the brain differences in people who stutter be used? When discussing our research with people who stutter, and others with an interest in this area, it’s become clear that just knowing about these findings can help. The cause of stuttering has been debated for many years, and a “nervous personality” has erroneously been offered as a likely explanation. Another unhelpful belief is that it’s possible to “grow” or “snap” out of this way of speaking. So, being able to point to a neurological difference located in brain regions controlling speech, can be a welcome reassurance that such myths have no basis.

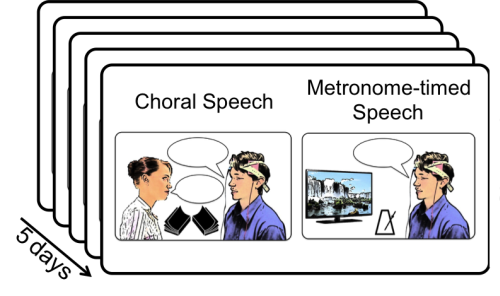

Image credit: An intervention session of the tDCS randomized controlled trial. Used with permission.

Image credit: An intervention session of the tDCS randomized controlled trial. Used with permission. Advances in neuroscience mean that brain imaging findings can now inform non-invasive brain stimulation studies aimed at increasing speech fluency. As speech therapy outcomes for adults who stutter can be limited, our team recently completed the first randomized controlled trial investigating whether transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) could be usefully applied in therapy. TDCS involves passing a very weak electrical current across two surface electrodes placed on the scalp, and through the underlying brain tissue. This changes the excitability of the targeted brain area. When it’s paired with a task, the change in brain excitability from the tDCS can interact with task-related brain activity, resulting in improved performance and learning. The parameters for safe, painless application of tDCS have been established from large body of research studies, and the equipment is portable, and relatively affordable. For these reasons tDCS has attracted interest as a therapeutic tool for conditions that affect how the brain functions.

We used two temporary fluency-enhancing techniques: reading along with another person, and speaking in time with a metronome. In combination with this, we applied tDCS over the left inferior frontal cortex – the key area for planning and executing speech movements which is relatively less active in people who stutter. We were interested in whether pairing tDCS with the tasks, practiced in 5 daily sessions, would increase speech fluency after the intervention was completed. Thirty adult men who stutter were randomly assigned to real tDCS or an indistinguishable “sham,” or placebo, tDCS. The group receiving real tDCS showed persistent improvement in their speech fluency six weeks following the intervention, compared to the group receiving sham. TDCS reduced stuttering symptoms by around 25%.

Our results show that tDCS is certainly a promising approach for fluency intervention, and we are continuing to study it’s use. However, the relationship between the fluency of our speech and our perception of ourselves as speakers is far from straight-forward. For this reason, increasing speech fluency may not necessarily give a person who stutters a useful therapy outcome. In fact sometimes feeling you are “chasing fluency” can be a particularly negative experience. For example, living with a covert stutter involves avoiding any possibility of stuttering, with the constant fear that a moment of disfluency might slip through. Overtly, speech appears completely fluent, but the burden to the person who stutters to maintain this illusion is huge. Speech and Language Therapy in the United Kingdom for adults who stutter is varied so that all experiences of stuttering can be addressed. Therapy may include approaches to increase fluency, to stutter with less struggle, or to build more positive thoughts and beliefs about living with a stutter. Some combination of these approaches often yields the best outcome for any one person.

Image credit: Design of the tDCS randomized controlled trial intervention. Used with permission.

Image credit: Design of the tDCS randomized controlled trial intervention. Used with permission. Of course, some people who stutter choose no therapy at all. An approach that is universally beneficial for educating us all about stuttering, and supporting those of us who have this condition, is to acknowledge the strength, resilience, and considerable talents of people who stutter. Five years on from the first airing of Educating Yorkshire, Musharaf Asghar is now a motivational speaker. He is an inspiration, not because his stutter has disappeared from his speech (it hasn’t), but because he speaks with confidence about his experiences of living with a stutter, as one facet of who he is.

Understanding the brain differences that are associated with stuttering, and using this knowledge to shape and improve interventions, is one of the many ways that we can support people who stutter to live the life they choose. If a person who stutters chooses to work on their speech fluency, non-invasive brain stimulation could allow us to give them the best possible outcomes.

Featured image credit: Brain by GR_Image. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post What can brain research offer people who stutter? appeared first on OUPblog.

Learning to live in the age of humans

A new “great force of nature” is so rapidly and profoundly transforming our planet that many scientists now believe that Earth has entered a new chapter in its history. That force of nature is us, and that new chapter is called the Anthropocene epoch.

In reshaping Earth to sustain our societies, we humans have altered Earth’s climate, polluted her atmosphere, oceans, freshwater, and soils, driven thousands of species extinct, and spread weeds, pests, and diseases around the world. Even as human populations continue to grow and develop, more than three quarters of Earth’s land is already covered by farms, pastures, cities and other human infrastructure, or fragmented into smaller parcels in the lands in between. While most humans are living longer, healthier lives and eating higher on the food chain, the rest of life on Earth is being pushed into the margins. More than 90% of Earth’s mammal biomass is now composed of humans, livestock, and pets. Should plastic pollution continue at current rates, there will be more plastic than fish in the sea by 2050. It is not hard to see why so many consider the Anthropocene to be an unmitigated disaster.

Can human societies change these trends and bend Earth’s trajectory towards a better future? Will the Anthropocene become a story of awakening and redemption, or a story of senseless destruction? At this point in Earth history, the Anthropocene is still young and the jury is still out. But even at this early stage, there are already many diverging narratives explaining the emergence of the ‘age of humans’.

Some see the start of the Anthropocene as a clean break from an earlier time when human societies lived within the limits of a ‘natural’ Earth system – a time when natural environments shaped human history, and never the other way around. Others, including the stratigraphers of the Anthropocene Working Group, recognize the continuous nature of anthropogenic environmental change and its deep roots in prehistory, yet still choose to focus on defining a discrete time boundary for the Anthropocene in the middle of the 20th century. Others look deeper still, observing significant human transformations of Earth’s biosphere, atmosphere, and climate starting in prehistory as the result of megafauna extinctions, deforestation and land clearing using fire, the tillage and irrigation of agricultural soils, the domestication and transport of species around the world, and other increasingly globalized social-ecological transformations that continue to shape our planet at increasing scales into the present day.

Outside the sciences, arguments rage over the meanings and societal implications of a new age of humans. The politics of inequality, environmental ethics, and the challenges of responsible action under conditions of potentially catastrophic global change have all been connected with the proposal to recognize the Anthropocene. Is naming an age of Earth history after ourselves anything more than the ultimate act of hubris by a species that is rapidly driving Earth to ruin? Will recognizing a time in which the natural world is reshaped by humans cause people to give up on efforts to conserve nature? Who is causing the Anthropocene? Is global environmental change – and global climate change in particular – the product of ‘human activity’ in general, or the result of a capitalist conspiracy among rich elites and the producers of fossil fuels? Indeed, billions of Earth’s poorest use hardly any fossil fuels at all – and yet will suffer the most from their planetary consequences. It is not hard to understand why the Anthropocene has emerged as a flashpoint of discussions about nature of humanity, the role of humans in nature, and even what it means to be human.

One thing is sure. At this time in which we change the world as we know it, we must also change the way we know the world. The Anthropocene calls on us to think bigger than our individual lives, to imagine the operations of an entire planet and its changes over timescales longer than human societies, from start to finish.

The Anthropocene tells us that, together, humans are a force of nature. On the road ahead, better and worse anthropocenes exist. The story of the Anthropocene has only just begun. There is still time to shape a future in which both humans and non-human nature thrive together for millennia. There is still a chance for each of us to write a better future into the permanent rock records of Earth history.

Featured image credit: lego doll the per amphitheatre by eak_kkk. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post Learning to live in the age of humans appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers