Oxford University Press's Blog, page 256

May 9, 2018

Who put Native American sign language in the US mail?

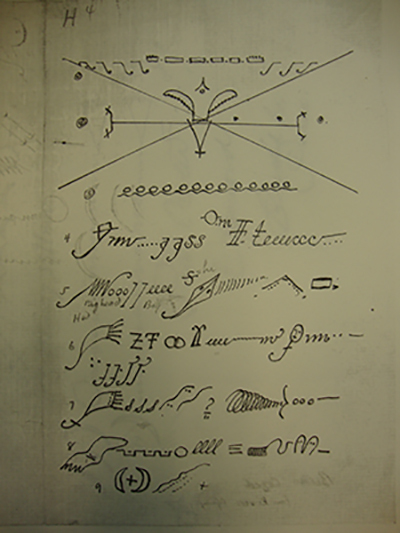

In 1890, a strange letter with “hieroglyphic script” arrived at Pennsylvania’s Carlisle Indian Industrial School. It was sent from a reservation in the Oklahoma Territory to a Kiowa student named Belo Cozad. Cozad, who did not read or write in English, was able to understand the letter’s contents—namely, its symbols that offered an update about his family. The letter provided news about relatives’ health and employment, as well as details about religious practice on the reservation.

Letter written using Kiowa sign language. Used by permission from Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

Letter written using Kiowa sign language. Used by permission from Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.A letter to Belo Cozad, a student at Carlisle Indian Industrial School, from his family on the Kiowa reservation. Used by permission from Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

While Belo Cozad understood the letter, Americans working at the school did not. Neither did reservation officials who saw the letter once Cozad returned to Oklahoma. Anthropologists working there sent a copy to the Smithsonian’s Bureau of Ethnology, where a staff member set out to understand it. Interviewed back on the reservation, Cozad provided “translations” of the letter. The anthropologists concluded that several Kiowas, though hardly all, knew this writing system. Although Cozad insisted that his parents and grandparents had long known the practice and taught it to him, the specialists concluded that it was of “recent origin.”

Letter written using Kiowa sign language. Used by permission from Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

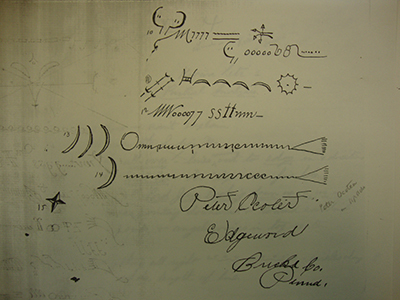

Letter written using Kiowa sign language. Used by permission from Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.The anthropologists were partly right. The system had only recently been put on paper. But the gestures and signs that inspired it, recently labeled by non-Natives as Plains Indian Sign Language, had been used by Kiowas for generations. Indeed, one of the Smithsonian workers likely recognized it from earlier work on Native signing systems. The marks on Cozad’s letter mimicked the signs for individual words. A circle followed by four loops signifies four brothers. Three horizontal lines stand for the number three. A box with vertical lines, followed by a swooping downward and then upward line, means that someone has been buried in a grave. Together, the signs tell Cozad that he no longer had four brothers, but only three. One had recently died and been buried.

Symbols relating the death and burial of Cozad’s brother. Used by permission from Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

Symbols relating the death and burial of Cozad’s brother. Used by permission from Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.With this letter, Cozad’s family took an old form, Plains Indian Sign Language, and adapted it for their new situation. With the hope of reaching their kin in boarding school, they had put signs onto paper and placed it in the US mail.

Kiowas displayed a similar capacity to adapt older forms from the realm of religious practice. Ritual gatherings, especially their version of the Plains Indian Sun Dance, were threatened by declining buffalo herds and, eventually, military supervision and criminalization. Even so, Kiowas found ways to adapt their Sun Dance rites to new conditions, including purchasing buffalo hides from Texas ranchers and choosing ceremony sites far away from government supervision.

They also experimented with new sources of sacred power. Between 1868 and the end of the century, some Kiowas borrowed peyote rites from neighboring indigenous peoples. Soon, Kiowas developed their own peyote songs and added peyote to the pantheon of beings and things imbued with power. Other Kiowas accepted the message of Wovoka, the Paiute leader of the movement that came to be known as the Ghost Dance. They danced with the expectation that relatives who had died and depleted buffalo herds would be restored. Still others considered Christian missionaries’ proclamation about Jesus as a powerful figure who provided healing in this life and heaven in the next.

Kiowa ritual life followed a pattern recognizable in the Cozad’s sign language letter, namely the adaptations of older forms for new and difficult situations. For generations, Kiowas had gathered to seek blessing, protection, healing, and empowerment from beings imbued with dwdw, or sacred power. At Sun Dances, these efforts focused on the sun and the buffalo. In other venues, Kiowas sought visions and healing that could be bestowed from powerful animals, plants, or places. Often, Kiowas presented offerings as they made supplications, or to signal their thankfulness when blessings were received.

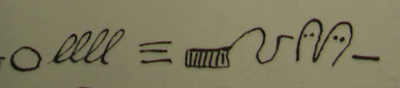

In their letters, Cozad’s family took the long-practiced gestures of sign language and sent them across the hundreds of miles that separated the reservation and boarding school. Kiowa religious life exhibited a similar pattern. For the sake of connecting family and maintaining land in a desperate colonial situation, Kiowas sought new ways to engage sacred power. Even as they looked to new sources, they maintained the postures of supplication, the same tokens of thanks. Cozad’s letter included references to these new practices. The writers tell Cozad, through signs, that Jesus is looking down over all the tipis and beyond in the four cardinal directions.

Symbols show Jesus looking over the Native Americans. Used by permission from Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

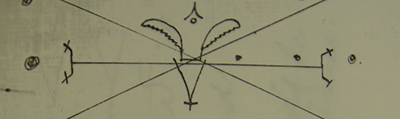

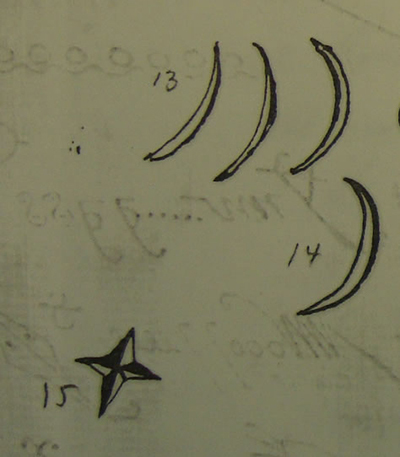

Symbols show Jesus looking over the Native Americans. Used by permission from Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.The relatives encourage Cozad to pray to Jesus. They also signal the diversity of religious forms among Kiowa people. At the letter’s end, through signs that stand for the moon and the morning star, the family relates that a fellow Kiowa has been out singing peyote songs.

Symbols relate how one Kiowa experimented with peyote rites. Used by permission from Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

Symbols relate how one Kiowa experimented with peyote rites. Used by permission from Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.In a period of unwelcome and devastating change, Kiowas did new things. They tried peyote rites and Christian prayer. They wrote letters and put them in the US mail. But all these things reflected older ways of being and doing. And all these things functioned to maintain family, kin, nation, and land in an increasingly perilous situation.

Featured Image: Old Pony Express Trail by dmtilley. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Who put Native American sign language in the US mail? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 8, 2018

Medical mycology: an introduction

The spectrum of fungal disease has evolved exponentially over the past four decades, and so has the emergence of fungal diseases as an increasingly important problem in global healthcare systems. If a medical mycologist who had retired in the 1970s returned to the discipline today, they would inevitably find it irrevocably changed—almost unrecognisable.

International travel, climate change, and antimicrobial drug resistance have all contributed to the endemic range of fungal pathogens and their toll on our health. However, despite a general agreement that the mycoses are becoming more important, our understanding of the true magnitude of the burden posed by these diseases and their socioeconomic impact remains largely incomplete.

In the video series below, Professor Neil A.R. Gow gives an overview of medical mycology as a specialty, and explains why a new generation of mycologists will face various important challenges in order to keep the spread of fungal disease at bay in the 21st century.

What is medical mycology?

What are the different types of fungi that cause disease in humans?

Fungal vaccines and disease prevention

The impact of anti-fungal drug resistance

The future of medical mycology

Featured Image credit: “Mold Growth Fungus Microorganism Mildew” by TheDigitalArtist. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Medical mycology: an introduction appeared first on OUPblog.

May 7, 2018

Section 4968 and broad-based endowment taxation

Congress added Section 4968 to the Internal Revenue Code in the comprehensive tax legislation adopted in December. Section 4968 imposes a tax on the investment incomes of some college and university endowments. Critics of Section 4968 disparage this new tax as selectively targeting what are widely perceived as wealthy, politically liberal institutions such as Harvard, Yale, Princeton, M.I.T., and Stanford.

As I have argued, there is a strong tax policy case for taxing the net investment incomes of all charitable endowments including donor-advised funds, community foundations, all educational endowments, and foundations supporting hospitals, museums, and other eleemosynary institutions. Like corporations and private foundations that currently pay revenue-generating income taxes, charitable endowments use public services and have capacity to pay tax. Such traditional tax policy criteria including equity and economic neutrality counsel that similar entities and persons should be taxed similarly. Just as corporations and private foundations pay income taxes to support federally-provided social overhead, by analogy, all charitable endowments, as similar entities, should pay similar taxes as well.

Section 4968 falls short of the goal of a comprehensive, revenue-generating tax on the universe of charitable endowments. Section 4968 is poorly designed to boot. Most anomalously, Section 4968 taxes some relatively small educational endowments while leaving other, much larger endowments untaxed. Section 4968 is best defended in political terms as an incremental step towards the kind of comprehensive tax on all charitable endowments suggested by conventional tax policy criteria.

In sum, the problem is not that Section 4968 goes too far but that it does not go far enough. For all relevant purposes, the charitable endowments not taxed today are similar to those that are taxed. By analogy, these currently untaxed endowments should also be taxed on their net investment incomes as these endowments use the same public services and have the same capacity to pay as the corporations, private foundations, and college and university endowments, which today are taxed.

In the final analysis, a tax on some or all charitable endowments raises the fundamental, politically-charged question which lies at the heart of most tax policy debates: Who should pay for public services? As long as the US levies a conventional corporate income tax and imposes revenue-raising taxes on private foundations, traditional tax policy criteria such as ability to pay, benefits received, economic neutrality, equity, revenue-generation, and administrability justify broad-based taxation of all charitable endowments. All such endowments utilize public services and have capacity to pay tax.

Section 4968 does not create such a broad-based endowment tax. It should be the harbinger of one.

Featured image credit: Yale university landscape by 12019. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Section 4968 and broad-based endowment taxation appeared first on OUPblog.

Learning on the job: The art of academic writing

Most academics don’t have formal training in writing but do it every day. The farther up the career ladder one goes, the more writing becomes a central activity. Most academic writing skills are learned ‘on the job’, especially by working with more experienced co-authors. Grants, papers, and even books are written to the best of the author’s ability and on the weight of the content.

This is changing though, as more universities are offering and often requiring academic writing courses. This can help significantly jump-start the process, but it is in writing up one’s own research that such skills are truly developed.

Many find the act of writing a first paper difficult, but it’s a task that gets easier with practice. How to prepare for this? The key to any solid paper in any field is solid research. There must be a story to tell; then it’s a matter of piecing together the ‘Big Picture’ with the details to build a narrative that fits venue and audience.

We continue to evolve as writers from childhood until our last words. From the start of your career to the end, these are the types of good habits that help make the writing process as ‘easy’ as possible:

Read, read, read, read and read as many publications on topics in your field as you can, as well as those that fall outside your area of expertise.

Seek out and work with experienced colleagues.

Talk to others about their paper writing and publication experiences – writing is only the beginning; you also have to navigate the publication landscape.

Ask questions and more questions – this is what science is about.

See if you can get practice reviewing papers (like for senior colleagues) – this is one of the best hands-on way to learn what makes a great paper and what doesn’t.

Look at and become familiar with the formats of different journals and understand why you’d want to publish in different venues.

Read yet more.

When it comes to writing up that first paper, the ease of the task will be proportional to the strength of the research. The importance lies not so much in whether it is aimed for a top tier or a more specialist journal, but whether it’s a ‘unit’ of research with a clear beginning and end and firm interpretation and conclusions. The best way to derail a paper writing attempt is to have too many conclusions that cloud the contents of the paper. That your work leads to many great follow-on questions is a strength.

Finally, regardless of whether you’re starting your first or your fifth paper, you can read about the art of writing. There are an increasing number of publications on writing good papers. One of the first I ever saw was by Phil Bourne. Now looking online brings up a larger variety of guides, for example on the principles of publication, tips to structuring papers from journal editors, and personal accounts of first-time experiences.

Whether or not you enjoy writing papers, it’s something that must be done in academia, and ideally as efficiently and effectively as possible. In the end, you want solid research that builds your ‘paper chain’ such that you become a known authority in your field. In the longer-term what counts is how that paper stands the test of time and how more research can be built on top of its findings.

Featured Image Credit: “Writing Write Person Paperwork Paper Notebook” by Free-Photos. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Learning on the job: The art of academic writing appeared first on OUPblog.

Towards a postcolonial nineteenth century

French and Francophone Studies is a vibrant and diverse field of study, in which research on nineteenth century literature, and research from the perspective of postcolonial theory, are thriving—and indeed represent particular areas of growth. What does it mean, then, to argue for a “postcolonial nineteenth century”? It would certainly be misleading to see the two areas as completely divorced or discordant. Postcolonial theory was, in part, born out of nineteenth-century studies and an interest in colonial discourse, with a comparative literary focus ranging across English- and French-language texts. This was, after all, among the principal specialisms of Edward Said, author of one of the founding texts of postcolonial studies, Orientalism, published forty years ago in 1978.

Much more recently, pioneering work has looked at colonialism in popular culture in the long nineteenth century, including phenomena such as the human zoos at World’s Fairs; other approaches have seen the republication and study of writing from and about France’s colonies. The French academic establishment, meanwhile, is now opening up to postcolonial approaches, thanks in part to the pioneering publications of Jean-Marc Moura and what may be a deeper politico-cultural shift in France itself. But there remain some important divergences of approach.

Nineteenth-century French studies as a disciplinary field defines itself primarily by its object of study, although this chronological emphasis is a flexible and expanding category. In contrast, postcolonialism (unlike “francophone literature”) defines itself not as a specific corpus but as an approach informed by a body of theory and driven by a concern with politics, ethics, and the rejection of imperialism. At times, distinct ideologies appear to shape the two disciplinary fields. Postcolonial reading of French texts tends to be an act of suspicion, informed by a conception of discourse as a product and perpetuator of a Foucauldian nexus of knowledge and power. On the nineteenth-century side, critical reading often seeks to reveal a text’s formal, generic, historical, or biographical dimensions. Much work in nineteenth-century studies has derived its energy from issues of literary form and genre, which (in France itself, arguably more than in the Anglo-American academy) has at times encouraged apolitical or universalist readings. Such approaches tend to see the work of art as having unquestioned value in itself, and pay less attention to the political context of its production.

Nineteenth-century French studies as a disciplinary field defines itself primarily by its object of study, although this chronological emphasis is a flexible and expanding category.

Postcolonial criticism, on the other hand, has tended to be wary of this concentration on literary form, which is seen as part of an elitist cultural capital and associated with stifling forms of canonicity. The divergences between the two approaches have in one respect tended to increase recently, with the rise of genetic criticism in France. The study of manuscripts, facilitated by new technical means, along with the “return of the subject,” has encouraged nineteenth-century studies to look at writing as an individual, idiosyncratic process rather than as part of a broader social discourse. This focus on authors stands in marked contrast to the approach by “area” that is more common in postcolonial criticism, which, after all, derives partly from wider approaches associated with “area studies.” Spatiality is, of course, itself an area explored by scholars of the nineteenth century, but the field remains, on the whole, implicitly structured in terms of authors or periods rather than spatiality.

There are, however, productive and exciting areas of crossover between these two fields. Cross-fertilization between the study of literary texts and visual, non-literary, or popular culture artefacts is one such area, as can be seen for example in the work over the past few decades of the Association connaissance de l’histoire de l’Afrique contemporaine (ACHAC). Long-standing areas of nineteenth-century studies, such as “orientalism” or “exoticism,” are increasingly being re-contextualized in terms of colonial discourse and practice. Travel writing and colonial-era literature require approaches that account for formal traits and individual idiosyncrasies, as well as deep-seated ideological tensions. And within postcolonial theory there have been new calls for an approach that would take into account the specificity of the literary, and formal, poetic or generic aspects. These conjunctions open up a dynamic, shifting, and highly enabling intersection between, on the one hand, the study of literary form, individual subjectivities, and the metropolitan socio-historical context, and, on the other, wider political contextualization in terms of colonial history and the postcolonial globalized world.

Featured image credit: Arab Horsemen by Eugene Fromentin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Towards a postcolonial nineteenth century appeared first on OUPblog.

What if your boss was an algorithm?

The world of work is going digital: an ever-growing number of start-ups are setting up online platforms and mobile “apps” to connect consumers, businesses, and workers—often for jobs lasting no longer than a few minutes. What started out as a small niche for digital “crowdwork” on platforms like UpWork and Amazon’s Mechanical Turk has grown into a global phenomenon. Some of the major players have quickly become household names: think “ride-sharing” companies Uber, Lyft, Didi, and Ola, delivery apps Deliveroo and Foodora, or casual task platforms Helpling and TaskRabbit.

New platforms are cropping up in industries from transportation to domestic care, from professional services to manual labour. They are at the vanguard of what is often called the “gig economy,” evoking the artist’s life in which each concert, or “gig,” is but a one-off task or transaction, without further commitments on either side. Its rise has been surrounded by intense public debate. Contradictions abound. To some, the “Uber economy” is merely the latest instantiation of runaway capitalism “screwing the workers”; to others, “collaborative consumption” is the foundation of fundamental improvements in our working lives.

Key to this business model are the powerful algorithms at the heart of platforms’ operations, designed to match consumers who need a task done with entrepreneurs in search of their next “gig.” The underlying quest is to remove as much “friction” as possible from each interaction. Beautifully designed apps with clever functionalities offer swift introductions, and make the gig economy fun and easy to use for both parties: drivers and passengers can see each other on their phones before a trip has begun; if you need help assembling new furniture, an algorithm will swiftly find the best—or cheapest—available handyperson.

This is the promise of a future of work in a digital world: clever algorithms will allow more and more of us to enjoy the thrills and rewards of life as a (micro-) entrepreneur. Instead of the tedium of 9-5 work in an office or factory under the ever-watchful eyes of a powerful boss, individuals can turn to a wide range of platforms to choose when, how, and where to work. This can be a real lifeline for groups traditionally excluded from the labour market, from homebound workers to those with criminal convictions. Anyone can easily find work through digital intermediary platforms such as Fiverr, where an online account is all that’s required to start earning money. Many stories are genuinely inspiring: the flexibility and additional income of gig work allow many to pursue their goals and fulfil long-held dreams.

Key to this business model are the powerful algorithms at the heart of platforms’ operations, designed to match consumers who need a task done with entrepreneurs in search of their next “gig.”

At the same time, however, a darker picture is also emerging: life as a “micro-entrepreneur” on many a platform is heavily conditioned by ever-watchful rating algorithms—a new “boss from hell” in the words of gig economy-critic Tom Slee. Instead of offering mere match-making services, many platform operators rely on constant algorithmic monitoring to ensure tight control over every aspect of work and service delivery. Additional elements—from compliance with platform policies to how quickly and often a worker accepts new tasks—are factored into the equation, with any deviation sanctioned in real time. Failure to comply can have drastic results—up to, and including, sudden, unexplained “deactivation.”

In many instances, algorithms will also assign work—and determine rates of pay. Depending on consumer demand, this means that the promised flexibility of on-demand work can quickly turn into economic insecurity, as gig income is highly unpredictable from week to week. The promise of freedom similarly rings hollow for many—not least because of carefully constructed contractual agreements, which ban some gig workers from taking platforms to court. Instead of enjoying the spoils of successful entrepreneurship, a significant proportion of on-demand workers find themselves trapped in precarious, low-paid work.

How should we respond? As regulators and courts around the world begin to grapple with these competing narratives of work in the gig economy, potential solutions abound: some insist that we ban the platforms in order to protect workers and consumers; others, that their development best be left alone lest innovative developments are stymied. In reality, however, neither of these extremes is likely to work: what we need instead is a level playing field on which new and existing businesses can compete. Employment law has a crucial role to play in this regard—even if the boss is an algorithm. This is not a question of enforcing burdensome rules to thwart innovation. Businesses can compete on an equal footing only if existing laws are equally applied and consistently enforced. Ensuring the full application of employment law is crucial if we want to realize the promise of the gig economy—without being exposed to its perils.

Featured image credit: Blogger by Free-Photos. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post What if your boss was an algorithm? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 6, 2018

Can electrical stimulation of the brain enhance mind?

It is almost philosophical to think that our mental representations, imagery, reasoning, and reflections are generated by electrical activity of interconnected brain cells. And even more so is to think that these abstract phenomena of the mind could be enhanced by passing electricity through specific cellular networks in the brain.

Yet, it turns out these tenets can be subjected to empirical experimentation. Groundbreaking discoveries made by Dr. Wilder Penfield with his patients undergoing open-brain surgeries to treat epilepsy opened a new field of brain research exploring physiological substrates of human memory. By applying electrical current in discrete regions of the brain’s cortex, Penfield induced a conscious experience of facts and events from the recent and distant past. For instance, one of his patients described re-living a childhood episode of a circus show with the vividness of detail associated with such a unique and captivating event. This phenomenal effect of electrical stimulation on memory experience was described in a series of patients stimulated in different brain regions.

In summary, the effect was found in defined areas of the cortex when electrical current was applied with optimal frequency and amplitude parameters for inducing the memory experiences. This led Penfield and colleagues to hypothesize that the stimulation worked by activating some specific physiological substrates storing memory traces of the remembered events. The idea is brilliantly simple. Stimulating networks of brain cells at a set of parameters, which match their physiological activity when memories are encoded, can reverberate a memory trace and result in its conscious experience. Waves of the applied electrical current would in a way entrain and re-activate groups of connected cells supporting specific mental representations. Around the time of these experiments, Polish neurophysiologist Dr. Jerzy Konorski and Canadian neuropsychologist Dr. Donald Hebb independently proposed a mechanism through which such connected groups of cells, aka neuronal assemblies, could form the physiological substrate for our mental constructs and their memory traces.

Since these initial ideas and findings, technological progress has been made to modulate these hypothetical substrates in attempt to enhance human memory performance. Several studies of individual cases or small groups of patients reported both positive and negative effects of electrical stimulation in a range of brain regions. The positive effect was manifested in improved reaction time or response accuracy in various tests probing spatial, semantic, and other forms of declarative memory for facts and events. Despite the mixed effects and other limitations in these pioneering studies, improving mental processes supporting memory performance with electrical stimulation became a tangible reality.

Stimulating networks of brain cells at a set of parameters, which match their physiological activity when memories are encoded, can reverberate a memory trace and result in its conscious experience.

This fascinating research can now be more robust and reproducible in the era of collaborative brain research projects. In our recent study, we used data collected from 22 patients stimulated in a range of brain regions during performance of a verbal memory task completed at multiple clinical centers. Four brain regions, which were previously implicated in declarative memory functions, were investigated for the effect of electrical stimulation on remembering lists of common words like “fish” or “rose.” We found that more words were remembered when one of the studied regions was stimulated (overlapping with the cortical area originally identified by Penfield). Electrical current passed through that region enabled the patients to recall more words as their abstract mental representation (or concepts, if you like) were generated. This time it was not the reaction time or response accuracy that was improved, but the memory for additional concepts of words when electrically entraining that brain region. And so was the subjective experience of one of the patients who reported that it was “easier to picture those words” in his mind.

Although this is still far from addressing the Konorski and Hebb models, we also observed a parallel effect of the stimulation on brain oscillations in the “high gamma” frequencies—a proposed indicator of neuronal assembly activity. We know that this activity is physiologically induced in response to word presentation for memory encoding. Electrical stimulation in the reported brain region enhanced the high gamma response, specifically on trials with words that ended up being forgotten (i.e. the poor encoding trials). This modulation of the gamma response reflected the behavioral change in memory performance—increased response was observed with memory enhancement, whereas the decreased response with a worsened performance. Thus, a concrete physiological process was linked to the effect on remembering mental concepts.

In conclusion, bridging the gap between the human mind and brain may not be as philosophical of a task after all. There are now at our disposal robust paradigms, effective tools, and tangible brain targets to reach out to the realm of declarative memory and cognition. The promise of physical devices to treat the abstract is very real.

Featured image credit: Image by Laura Miller, Mayo Clinic laboratory. Used with permission.

The post Can electrical stimulation of the brain enhance mind? appeared first on OUPblog.

Are we to blame? Academics and the rise of populism

One of the great things about being on sabbatical is that you actually get a little time to hide away and do something that professors generally have very little opportunity to do – read books. As a result I have spent the last couple of months gorging myself on the scholarly fruits that have been piling-up on my desk for some time, in some cases years. I’ve read books on ‘slow scholarship’ (Berg and Seeber, 2016) and ‘How to be an academic super-hero’ (Hay, 2017); books on ‘radical approaches to political science’ (Eisfeld, 2012); brilliant books on The festival of insignificance (Kundera, 2015) and In Defence of Wonder (Tallis, 2012); and even novels on university life, such as Stoner (Williams, 2012). What fun it is to soak yourself in the literature! To swim from genre to genre, from topic to topic with a little more freedom to explore beyond your micro-specialism than is ever usually possible and, through this, to garner new insights.

That is until an argument and insight makes you stop and tread water; to question your intellectual tribe and its contribution to society; that leaves you with a sense that you may now be ‘not waving but drowning.’

To some extent Stephen Pinker’s Enlightenment Now (2018) is the literary equivalent of being hit over the head while open water swimming by the chap in the guide boat that was supposed to be looking after you.

Pinker’s position is – simply put – that ‘those angry people don’t know how lucky they are.’ His argument is as simple as it is bold: overall the world is not declining into chaos and disaster but ‘people are getting healthier, richer, safer, and freer, they are also becoming more literate, knowledgeable, and smarter….People are putting their longer, healthier, safer, freer, richer and wiser lives to good use’. There is no ‘hellish dystopia’ but a world defined by progress based upon the insights of science and the Enlightenment. Pinker offers a powerful polemic that is almost bursting with apparently unquenchable optimism. From sustenance to health, from peace to equal rights, through to quality of life and the environment, the world has never been a better place to live in. Did you know that that Americans today are 37 times less likely to be killed by lightning than in 1900, thanks to a combination of better meteorological forecasting, electrical engineering, and safety awareness? Pinker writes that his favorite sentence in the whole English language comes from Wikipedia, ‘Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor.’ The word ‘was’ is what he likes.

In a somewhat odd turn of argument Pinker focuses upon Friedrich Nietzsche as the root of all counter-enlightenment evil. And yet when reading Enlightenment Now Nietzsche’s phrase regarding ‘philosophizing with a hammer’ sprang to mind due to Pinker’s emphasis on the world as understood (and only understood) through data-driven graphs. Variations of which appear over-and-over, each one measuring an apparently indisputable measure of human progress but hitting you over the head, wearing you down, like the dull data thud of progress, pushing towards the hypothesized tipping-point when you surrender and concede defeat to the inevitability of progress past, progress present, and progress future.

The problem is, however, reconciling this vast body of data on global human progress with the rise of populism, which is in itself reflective of a large amount of social frustration and anger amongst large sections of the public who don’t ‘feel good’ but feel ‘left behind’ (Wuthnow, 2018), ‘strangers in their own land’ (Hochschild, 2016 – by far the best book I have read for years) or part of the forgotten ‘périphérique’ (Guilluy, 2015).

And yet if life is improving in relative terms for most people, why have so many people proved attracted to populist temptations? Who or what is to blame?

‘I believe that the media and intelligentsia were’ Pinker writes ‘complicit in populists’ depiction of modern Western nations as so unjust and dysfunctional that nothing short of a radical lurch could improve them.’ This intelligentsia includes the social and political sciences, and although he notes ‘It may sound quixotic to offer a defence of the Enlightenment against professors’ he proceeds to rally against the ‘dystopian rhetoric’ of academe, the cultural pessimism of professors, and even accuses them of poisoning voters against democracy. Academics are, apparently, ‘progressophobes’ who chip away at the public’s confidence in conventional politics and through this have unwittingly created a vacuum that populism has filled.

Pinker’s polemical scientism was clearly designed to enthrall and enrage in equal measure and to this extent I can simply light the touch paper by pointing the reader to John Gray’s review in the New Statesman.

I am not really that interested in Pinker’s book. It is flawed from too many angles. Moreover, the academics and cultural pessimists that he blames are generally sociologists and critical theorists such as my old friend Zygmunt Bauman and the terror of modernity himself, Slavoj Žižek. And yet I could not escape a vague sense of uneasiness; a feeling that in some oblique and indirect way there might be a link between the critique of the ‘new optimists’ and the psycho-analytic temperament of political science. Not only has the discipline’s longstanding focus upon ‘endism’, crises, and failure been well documented, even its more quantitative approaches tend to be laden with fairly pessimistic assumptions about human nature.

I am, of course, and out of necessity, painting with such thick strokes on such a wide canvas that my argument may not tolerate stress-testing through detailed investigation, but humor me for just a little while longer and consider the titles of the leading books on democratic politics and performance in recent years.

The End of Politics (Boggs, 2000)

Democratic Challenges, Democratic Choices (Dalton, 2004)

Why We Hate Politics (Hay, 2007)

The Life and Death of Democracy (Keane, 2009)

Saving Democracy from Suicide (Lee, 2012)

Uncontrollable Societies and Disaffected Individuals (Stiegler, 2013)

Democracy Against Itself (Chou, 2014)

Against Elections (Van Reybrouck, 2016)

Four Crises of American Democracy (Roberts, 2017)

Democracy in Chains (MacLean, 2017)

How Democracy Ends (Runciman, 2018)

Suicide of the West (Goldberg, 2018)

The People Versus Democracy (Mounck, 2018)

Even the most cursory glance at the titles of the books paints a pretty bleak portrait of crisis, failure, and decline. John Kenneth Galbraith once advised that if you ever want a lucrative book contract, just propose to write The Crisis of American Democracy and it appears that there may have been some truth in this advice (at least in the minds of publishers thinking about potential sales). This is true to the extent that even when the arguments that reside within the pages of several of the books mentioned above are as balanced and measured as they are coherent and constructive, they are published under a title that resonates with ‘endism’.

Therefore if democracy is not in terminal decline the general message emanating from political science is that it is in pretty bad shape. Put slightly differently and with Pinker’s critique in mind, it is hard to find a positive vision within the discipline that sees the world’s problems against a backdrop of progress. That may well be all and good; I’m certainly no apologist for capitalism but it did at least make me stop and think….

Featured image credit: Bookish photo by Claudia. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Are we to blame? Academics and the rise of populism appeared first on OUPblog.

How to write anything

“I’m going to make a lot of money, and I’ll hire someone to do all my writing for me.” That was the rationale offered by a student many years ago for why he should not have to take a required writing course. A snarky comment crossed my mind, but instead I mentioned to him that if he had to hire someone to ghostwrite everything he would have to write in his life, it could cost him a small fortune.

The idea that there was more to writing than college term papers seemed to satisfy him. For me, it raised a new concern: just how do we help people write effectively about so many things—about practically anything?

Whether it’s a résumé, catalog copy for chocolate or flowers, a profile of a scientist, an endorsement of a political candidate, a safety manual, or a users’ guide, the key is to find some good models and study the rhetorical moves that other writers make. “Rhetorical moves” is a term introduced by linguist John Swales, and it refers to the different steps that a writer makes in constructing a text in a given genre—a bit like the standard opening strategies of a chess game.

Swales originally pursued the idea of rhetorical moves to analyze academic research writing, with its steps of establishing a territory, a niche, and a claim. But the idea of analyzing a genre of writing into a set of purposeful steps can be—and has been—fruitful beyond the domain of research writing.

For someone aiming to be a general-purpose professional writer, it pays to create a personal guide to different types of writing. When you find a piece of writing that you think is especially effective, sketch out its structure move-by-move. Doing this doesn’t require hours of pondering or a PhD. It can be a quick sketch, like the one below that captures the shape of many an opinion essay.

Describe what many people think about an idea in the news.

Introduce a new perspective that suggests there is more to this.

Offer a quote or two from an expert or a relevant personal anecdote about the new perspective.

Sum up by explaining what we should do next.

This bare bones skeleton has four moves—conventional wisdom, a new insight, expertise, and call to action—and it leaves plenty of room for a writer to personalize an opinion essay. The rhetorical moves are a skeleton not a straightjacket.

Here is another example. A personal profile might have a structure like this:

Tell who the person is and why they are significant.

Provide a chronology of relevant life events.

Interpret the person’s accomplishments and challenges, with quotes.

Include a telling, final detail or fact about them that brings it all together.

The profile format can be adapted further— to application essays or even obituaries or to a description of an organization or business.

Try looking for rhetorical moves with models of your own choosing—food, movie, and book reviews, for example, résumé or cover letters, and solicitations or complaints. Soon rhetorical moves will be cropping up everywhere you look.

Analyzing the rhetorical moves of your favorite bits of prose has another benefit. You will quickly become comfortable enough with the rhetorical moves to begin to adapt and play with them. You might, for example, open a profile without identifying the subject directly, letting the readers guess the identity at first. Or you might write an opinion piece that ends by lamenting rather than calling to action.

Being able to write anything at all is an exercise in reading for rhetorical moves and then adapting and extending those moves. With some practice and time, you’ll have an all-purpose rhetorical toolbox that will enable us to meet deadlines, communicate without fear, grow as a writer, and have fun writing.

And think of all the money you’ll save by doing it yourself.

Featured image credit: “QWERTY” by Jeff Eaton. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How to write anything appeared first on OUPblog.

May 5, 2018

The Second World War as refugee crisis

On this, the 74th anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe, when refugee camps across the globe are overflowing, it’s worth considering that the war itself was the violent climax of a massive refugee crisis. Even before the refugee problems caused by the First World War and the Bolshevik Revolution could be solved, Hitler’s seizure of power in early 1933 convinced Jews and left-leaning political opponents of Nazism to leave their homes. Not long after, refugees from the Spanish Civil War trekked into southern France, followed by millions of families fleeing from the Wehrmacht’s blitzkrieg through western Europe.

The response of the Vichy French and German occupation authorities to this pile-up of refugees was to allow most of them to return to their homes and to put the rest under police control, either under house arrest or in woefully inadequate internment camps. Some chose not to stay where they were told, thereby turning themselves into fugitives. Over the course of the occupation, other categories of refugee-fugitives slipped into the increasingly complex clandestine world. They included Allied soldiers who had evaded capture in 1940 or escaped from POW camps; resisters who could no longer stay in their legal lives; Jews who refused to report for deportation; young men and, in a few cases, women, who declined compulsory labor in the Third Reich or who left their war jobs; and downed Allied aviators. On the surface, a Jewish grandmother and an American pilot didn’t have much in common, but they were both being hunted by the authorities.

It was no easy task to live clandestinely under Nazi occupation. Everyone over the age of 16 was required to carry a range of identification papers including a standard ID card plus (depending on the situation) a birth certificate, a baptismal certificate, a marriage certificate, a work certificate, and travel passes. Police of all varieties—regular police, currency police, secret police, military police—could and did demand to inspect civilians’ papers in public and private spaces. But the net of surveillance stretched even further to include that most basic necessity: food. Because food was rationed, fugitives needed either illegal ration coupons or enough cash to pay black market prices. Very few commanded the resources to survive illegally without help.

Even so, thousands of men and women accepted those risks either by hiding refugees or by working together with other like-minded resisters in escape lines.

The civilians who extended such aid became resisters by that very act of generosity. A rescuer, as those who assisted Jews are called, or a helper, as those who assisted non-Jewish fugitives are called, could either hide a fugitive indefinitely or find a way to get that person out of occupied territory, usually to Switzerland or Spain. In doing so, a helper or rescuer took grave risks. Although a local constable might look the other way, the Abwehr (German secret military police) ruthlessly pursued anyone who helped aviators. Torture, deportation to the concentration camps, and death were always a possibility whenever a civilian helped a fugitive. Even so, thousands of men and women accepted those risks either by hiding refugees or by working together with other like-minded resisters in escape lines.

While refugee-fugitives and their helpers moved through the clandestine world of occupied Europe, the authorities were moving millions of other civilians, quite legally, out of their home countries in order to work or fight for the Third Reich. Indeed, at the war’s end so many people had been driven from their homes by the military destruction or taken from their homes by the occupying forces that the Allies created a new category of refugee which they called “displaced persons.” The first manifestation of the new United Nations to go into operation, because it was the most critically needed, was the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), a predecessor of today’s United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

The world wars launched the first truly global refugee crisis in modern times. In 1945 the UNRRA counted over 15 million refugees and displaced persons in Europe alone. Regrettably, the World Economic Forum reports that the number of displaced persons in the world today has risen to 65.6 million, 25 million of whom have left their own country. Encouragingly, there are still men and women, the heirs to the resistance’s helpers and rescuers, who are willing to extend a helping hand to refugees.

Featured image credit: Olympics by Nicholas Blumhardt. CC By 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The Second World War as refugee crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers