Oxford University Press's Blog, page 254

May 19, 2018

Child’s play: pioneers of child psychoanalysis

Psychoanalysis, a therapeutic method for treating mental health issues, explores the interaction of the conscious and unconscious elements of the mind. Originating with Sigmund Freud in the late 19th century, the practice has evolved exponentially in terms of both treatment and research applications. Much of Freud’s theory acknowledged that childhood experiences often affect individuals later in life, which was expanded upon by analysts who believed that mental health issues can affect individuals at all stages of their life. Child psychoanalysis has developed into a well-established technique for children and adolescents, with specialised approaches to working with younger individuals.

When considering the history of this specialism, a few key figures come to mind. Melanie Klein, Donald Winnicott, and Anna Freud began work with adolescents and infants as young as three years of age. Among a variety of techniques, each of the analysists incorporated elements of play in their therapeutic approaches as a means of understanding adult associations, behavioural and internalised expression, or in order to develop an authentic self.

Below is a brief introduction to each of their contributions to the field:

Interested in finding out more? Here are some additional facts about the lives and work of Melanie Klein, Donald Winnicott, and Anna Freud:

In 1914, Freud took a holiday in England but became an enemy alien when war broke out. After returning to Vienna, she began work as an apprentice elementary school teacher, qualifying six years later and joining the school staff. She remained a teacher—in the widest sense—all her life.

Despite being exempt from wartime service, Winnicott interrupted his studies in 1917 and joined the Royal Navy, to serve on a destroyer as a surgeon-probationer. During his downtime on the ship, he tackled the novels of Henry James.

Modernist writer Virginia Woolf found Klein to be a “woman of character and force and some submerged—how shall I say—not craft, but subtlety: something working underground. A pull, a twist, like an undertow: menacing. A bluff grey-haired lady, with large bright imaginative eyes.”

Analysis of one family member by another, or even by a close friend, is considered unacceptable in contemporary analysis. Yet in 1918, Sigmund Freud did not set a precedent and he would often analyse his daughter Anna. Klein also analysed her sons, Erich and Hans, as well as her daughter Melitta. Unlike Freud, however, she published their analyses under pseudonyms. No records exist of Freud’s analysis of Anna.

In 1936, Winnicott’s work was supervised by Klein, whose influence in the British Psychoanalytical Society was substantial. Winnicott was attracted to many of Klein’s ideas but always processed them in the light of his own clinical experience. Winnicott remained an independent thinker as the ideas he valued, whether Klein’s or not, often underwent alteration.

There were disputes between Klein and her followers and the psychoanalytic refugees from Vienna and Berlin, led by Freud, who strongly objected to what they regarded as the “London-centred doctrinal deviance” of the Kleinian group. The two groups disagreed over the depth of interpretation of the unconscious, and the presence, or absence, of transference in children. These disagreements led to a series of Controversial Discussions held between 1941 and 1945, moderated by a “Middle Group” that included Winnicott. The differences were never fully resolved, but the debate ended in a compromise whereby two separate training groups were organized. A split in the society, though threatened, was averted.

Featured image credit: Antique Wooden Train by Michael Bergmann. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Child’s play: pioneers of child psychoanalysis appeared first on OUPblog.

Richard Foley answers questions on the culture of research in academia

Due to current political climate, questions on funding, and dwindling enrollment size, academia has never been as challenged as it is today. Richard Foley, a philosopher and former dean, pushes back against these critiques. He spoke to Oxford University Press editor, Peter Ohlin, on why the arts, humanities, and sciences research should be celebrated.

Ohlin: Much of your recent research on the differences between the sciences and humanities is similar to C.P Snow’s famous essay from half a century ago, but you also issue a call for universities to defend a culture of research. What do you mean by “culture of research”?

Foley: Above all it’s a culture that treasures and finds ways to support intellectual achievements, especially long-term ones. Among its presiding values is that not every inquiry should be assessed in terms of immediate usefulness. Many topics are such that it shouldn’t be quick and easy to have opinions about them.

Ohlin: Why is it important for universities to support research?

Foley: Because over the centuries universities have proven to be indispensable for the collection, preservation, and production of knowledge.

Ohlin: Is it still necessary for them to play this role?

Foley: Yes. In the latter part of the twentieth century, it had sometimes seemed as if the battles to value knowledge and expertise were largely over. Now, from a vantage point well into the twenty-first century, it’s painful to see this isn’t the case. Just as universities, as one of the most long-lived of human institutions, have played a crucial role in other epochs in protecting knowledge, they need to do so in our time.

Ohlin: Why is the battle to value knowledge still being fought?

Foley: Political and cultural forces have eroded respect for specialized knowledge and expertise, helped along by the charge that unbiased inquiry and opinion are myths, leftover illusions from simpler times.

Ohlin: Is this charge warranted?

Foley: Human inquirers are imperfect. So perfect neutrality is not in the offing, but disinterestedness can still function as an ideal that inquirers can do better or worse jobs at approximating. Unfortunately, whenever there is imperfection, there are also misdirected impulses to write off whatever is not utterly spotless, which in turn invites a politicization of expertise and even information itself.

Ohlin: What are the effects of this politicization on research universities?

Foley: It contributes to an undermining of their standing of and an erosion of their financial support. It’s more accurate to say, however, that this is so in some regions of the world but not all. A peculiarity of our time is that the United States and United Kingdom, whose research universities have been the envy of the world, seem to be losing their appetite for maintaining them, while other countries that have lacked them are now eagerly building them.

Ohlin: The UK has a long tradition of great universities, but how and when did the US become a leader in higher education?

Foley: The decades following World War II produced a golden period of higher education and research in the US. So successful were the investments during this period that American universities, along with their British counterparts, came to dominate international rankings. According to the “Shanghai Ranking,” 8 of the top 10 research universities of the world are in the US or UK. The London Times Higher Education Ranking reaches similar results: 7 of its top 11 universities are US- or UK-based.

Sometimes the humanities and sciences are thought of as rivals, but a healthy culture for research for both is necessary for either to thrive in the long run.

Ohlin: If support for higher education and research remains tepid in the US and UK, what will be the result?

Foley: Other countries will gladly take their place, thereby attracting a greater share of the top international scholars, the most talented students, and the most important research projects. Indeed, this has already begun to happen. On the other hand, support for research and higher education shouldn’t be seen as a zero-sum game. A continuation of the tradition of strong universities and research cultures in the US and UK is compatible with their development in other parts of the world. There’s no scarcity of important projects waiting to be done, and no foreseeable end to the need for universities to train new generations to students capable of working on them.

Ohlin: In addition to financial resources, what’s needed for universities to build or preserve robust research universities?

Foley: Two commitments have been at the core of universities throughout their long history and remain critical today. The first is a commitment to a long view, with its attendant recognition that many inquiries require long gestation periods. The second is a commitment to a wide view, with an appreciation for the full breadth of issues of interest to humans.

Ohlin: Does this “full breadth of issues” include those addressed by the humanities as well as the sciences?

Foley: Most definitely. Sometimes the humanities and sciences are thought of as rivals, but a healthy culture for research for both is necessary for either to thrive in the long run. The history of computing is a great object lesson. Logics, developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by philosophers, were utilized a century later by computer scientists to create electronic circuits of immense power.

Ohlin: How do universities create a healthy research culture for both the humanities and sciences?

Foley: Most of all, they need to understand that the issues, aims, and methods of the humanities and the sciences are different, and this is not to be regretted. On the contrary, it’s a good thing. Their differences complement one another. That which escapes the sciences lies at the heart of the humanities, and the reverse is also true. The sciences provide insights that cannot be delivered by the humanities. It bears repeating that they’re not rivals.

Featured image credit: Chairs by Nathan Dumlao. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Richard Foley answers questions on the culture of research in academia appeared first on OUPblog.

May 18, 2018

The challenges of training future surgeons in the current NHS

Following the publication of the Government consultation Modernising Medical Careers in 2003, UK postgraduate medical training for doctors has been extensively reformed. These reforms have resulted in a competence-based training system, centred on a structured syllabus that defines the knowledge, professional behaviours, core clinical procedures, and clinical performance required for training.

General surgical training consists of two years of core surgical training followed by six years of higher surgical training. The specialty training is broad, encompassing a number of subspecialties including breast, colorectal, endocrine, upper gastrointestinal, transplant, and trauma surgery. Said training is traditionally delivered on the job in the form of an apprenticeship, and the trainee is required to participate in operative lists, ward rounds, clinics and endoscopy lists; rotating through placements in different subspecialties.

However, the current working climate of the National Health Service (NHS) is posing a number of challenges to delivering surgical training alongside the provision of routine clinical practice. The implementation of the European Working Time Directive to clinical training in 2009 has limited the maximum working week to 48 hours, and this has invariably impacted on the amount of clinical exposure and experience that can be attained by trainees within the remit of predefined specialty training programmes. This is particularly true for surgical training, which requires trainees to become proficient in operative, as well as clinical, management.

The current working climate of the National Health Service (NHS) is posing a number of challenges to delivering surgical training alongside the provision of routine clinical practice.

The pressures currently being faced by the NHS are also affecting the quality of surgical training. The NHS must meet performance targets, including the 62 day treatment target for cancer diagnoses, and the 18 week target non-cancer diagnoses. These targets require maximum efficiency when it comes to planning consultant surgical lists. Therefore, it is becoming increasingly difficult to plan traditional “training lists” with suitable time and cases allocated towards teaching. In addition, a lack of beds for post-operative care due to urgent admissions is increasingly impacting service provision, resulting in cases being delayed or cancelled on an on-going basis. All of these factors are reducing the opportunities for trainees to participate in a list, and are invariably impacting on the acquisition of surgical skills.

Operative training is affected much more over the winter months, when seasonal clinical epidemics such as influenza often result in critical bed pressures, and have led to many NHS trusts having to cancel elective, non-cancer and non-urgent operations over increasing periods for several years. The NHS has tried to mitigate the impact of these conditions on patient care by commissioning the use of clinical facilities in the private sector for elective referrals, in order to be able to meet NHS targets in surgical care. This commissions consultants’ time to deliver clinic appointments and surgical lists in private hospitals. Furthermore, a reduction in surgical training numbers and increasing rota gaps at all levels of postgraduate medical training has generated a skeleton service within many, if not most, NHS trusts. As such, is extremely difficult to free up surgical trainees to attend and participate in these lists.

In the face of these challenges, surgical training programmes are adapting, and both trainees and trainers have developed innovative approaches to support training. The acquisition of core clinical and surgical knowledge is supported by monthly mandatory surgical teaching programmes in all deaneries.

A number of books support the learning of surgical techniques and procedures, as well as applied surgical anatomy and case-based clinical management. Online learning portals are also becoming more popular for this type of learning. Over the last ten years, acquisition of knowledge relevant to both core and higher surgical training syllabi has been supported by an increasing number of surgical distance learning Masters programmes provided by a number of universities, including Oxford, and these have become increasingly popular with trainees.

Operative training is being successfully supported by simulation in a number of different environments. Procedural training is delivered at junior surgical training days to support acquisition of basic surgical techniques relevant to a number of surgical procedures, such as port site insertion and suturing, as well as basic procedures such as drainage of abscesses and hernias, using simulated models of synthetic materials or meat. Table-top laparoscopic simulator kits are becoming available on the market, which allow trainees to become comfortable with working in the laparoscopic environment. Computer-based simulators are increasingly present in hospitals and training centres, which facilitate a stepwise procedural learning of techniques such as gallbladder removal and endoscopy. Procedural training is also provided outside of training programmes through a number of courses. Trainees are expected to pass a number of core courses as part of their training, including Basic Surgical Training and Basic Laparoscopic Skills courses. However, there is also a wide variety of popular courses available for different surgical procedures, which involve simulated models, live patients and cadavers, and are more often than not paid for by the trainees themselves—keen to develop their surgical competence.

Computer-based simulators are increasingly present in hospitals and training centres

In addition to clinical and procedural training, mentoring by seniors and consultants plays an essential role. Mentoring provides pastoral support, career guidance, and often encourages the acquisition of professional behaviours. The Royal Colleges have acknowledged the importance of mentoring and are introducing structured mentoring programmes that can support all trainees in this way.

In conclusion, it is a challenging time for surgical training in the current clinical environment, especially with a health service under increasing pressure. The Royal Colleges have made recommendations for improving training, and a number of reforms are being instigated including run-through training. There is hope that this may allow some flexibility in acquisition of training around service pressures, but this remains to be seen.

Featured image credit: Surgery by Engin Akyurt . CC0 via Pixabay .

The post The challenges of training future surgeons in the current NHS appeared first on OUPblog.

May 17, 2018

First they came for Josh Blackman: why censorship isn’t the answer [video]

Having been thinking, reading, speaking, and writing about “hate speech” over the last four decades, I had come to believe that I had nothing new to say, and that all arguments on all sides of the topic had been thoroughly aired.

That view began to change several years ago, as I started to see increasing activism on campus and beyond in support of various equal rights causes. Having been a student activist myself, I have been thrilled by the recent resurgence of student engagement. I have been disheartened, however, by the fact that too many students and others have called for censoring speakers who don’t share their views, apparently believing that freedom of speech would undermine the social justice causes they champion.

Anecdotal reports, as well as polling data, forced me to recognize that neither I nor others who advocate robust freedom of speech, as well as equal rights, had sufficiently explained our position. We clearly had not persuaded many students and others that equal justice for all depends on full freedom of speech for all.

A recent case in point: CUNY law students disrupted Professor Josh Blackman’s 29 March talk on “The Importance of Free Speech on Campus”—a special irony—with extended heckling, posters that declared “Fuck the Law,” and other epithets that could themselves be considered “hate speech.” (I use quotes because “hate speech” is not a legal term of art, with a specific definition; rather, it is deployed to stigmatize and suppress widely varying expression. The term’s most generally understood meaning is expression that conveys hateful or discriminatory views against specific individuals or groups, particularly those who have historically faced discrimination.)

Having watched the video of the whole disturbing CUNY incident, I admire Professor Blackman’s handling of the disruptions with dignity, reasonableness, and a willingness to persist in speaking. But I was sad to see that the slogan-shouting students—future public interest lawyers!—apparently had so little confidence in their ability to express their disagreements via rational discourse. In contrast, I have great respect for the African American student who said he disagreed with Blackman and therefore was sitting in the audience in order to listen and respond to his views.

One reason for the CUNY students’ fury was that Blackman’s talk was sponsored by the Federalist Society, whose mission statement describes it as “a group of conservatives and libertarians interested in the current state of the legal order.” Even if one disagrees with some Federalist Society positions, it must be recognized that the group, to its credit, promotes debate and discussion of constitutional law issues. Moreover, some of its core founding principles could have come straight from the ACLU’s playbook: that “the state exists to preserve freedom”; and “that the separation of governmental powers is central to our Constitution.”

Some of the reasons why Professor Blackman was deemed persona non grata at CUNY Law School also apply to me (despite whatever “liberal” credentials might be attributed to me as the immediate past president of the ACLU). For example, I too have spoken about free speech issues at the behest of the conservative- and libertarian-leaning Federalist Society (whose events are often co-sponsored by the liberal-leaning American Constitution Society, which was founded precisely to serve as a counterweight to the Federalist Society).

It is important that we continue to engage in vigorous discussions about the appropriate limits on controversial speech, including what its critics denounce as “hate speech.” While these topics have been perennially debated, we must always consider pertinent new information. For example, recent evidence shows that comparable countries that censor hate speech have experienced no decline in the amount of either hateful speech or discriminatory behavior; to the contrary.

According to the European Parliament, hateful speech and bias crimes have increased in European Union countries despite their strong “hate speech” laws. In Germany, which has some of the strictest “hate speech” laws in the world—including laws against Holocaust denial—Chancellor Angela Merkel recently announced the country’s first-ever commissioner to combat anti-Semitism, in light of the dramatic rise in anti-Semitic attitudes, speech, and violence, especially among the young. In addition, the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, an expert body that monitors implementation of European “hate speech” laws, reports that such laws threaten “to silence minorities and to suppress criticism, political opposition and religious beliefs.”

These findings are echoed in a report released in March by Article 19, the British-based organization that champions freedom of speech worldwide (taking its name from the free speech guarantee in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights). Based on a review of “hate speech” laws in six EU countries, the report concluded that these laws are “open to political abuse, including against precisely those minority groups that laws should protect.”

Recognizing the ineffectiveness of such laws, many European human rights advocates and agencies are now urging more reliance on America’s approach of counterspeech as the antidote to speech we deplore.

Will students and others calling for censorship of “hate speech” and cancellation of controversial campus speakers take heed of these arguments? Despite incidents like the one at CUNY, I have reason to be hopeful. Effective counterspeech has been increasingly utilized by minority students themselves, and by other people who are members of groups that are being disparaged.

In addition, resources for countering “hate speech” and bias crimes are abounding, with a wealth of information, training, and organizations that empower all of us to speak up both for ourselves, if we are disparaged, and for others whom such speech targets. Also abounding are non-censorial measures for curbing the potential harm to which constitutionally protected “hate speech” is feared to contribute: discrimination, violence, and psychic injuries.

To be sure, campuses and other arenas in our society must strive to be inclusive, to make everyone welcome, especially those who traditionally have been excluded or marginalized. But that inclusivity must also extend to those who voice unpopular ideas, especially on campus, where ideas should be most freely aired, discussed, and debated. Encountering “unwelcome” ideas, including those that are hateful and discriminatory, is essential for honing our abilities to analyze, criticize, and refute them.

Featured image credit: “black-microphone-64057” by freestocks.org. CC0 via Pexels .

The post First they came for Josh Blackman: why censorship isn’t the answer [video] appeared first on OUPblog.

Exactly what is our problem with the political class?

Right now, the British people do not like their politicians. A common target of this dislike is not a singularly unpopular politician but rather the so-called “political class,” a group supposedly led by career politicians who collectively feed from the trough of publicly funded political institutions, who fail to represent the public at large, and who are a noxious mix of self-serving indifference. The overarching narrative surrounding the political class often takes one of three forms: attacks based on who they are (their personal characteristics), attacks based on what they do (their behaviour), or attacks based on what they think (their attitudes).

The most common element of the political class narrative focuses on the lack of characteristic diversity held by its members. This might be the reasonably vaguely specified characteristic of working in a job that relates to politics before becoming an actual Member of Parliament (MP), or the more precise one of being a politician who was educated at “Oxbridge,” for example. There is, however, a solid amount of evidence supporting the idea that the political class lacks characteristic diversity: it is overwhelmingly male and white, with just 32% of MPs being women and 8% from ethnic minority backgrounds. It is also increasingly composed of individuals who have worked in politics in a professional capacity prior to becoming MPs, the percentage of MPs with the background growing from the low single digits in 1979 to almost 20% now.

The most common element of the political class narrative focuses on the lack of characteristic diversity held by its members.

Another characteristic failing levelled at the political class is that its members are significantly wealthier than the population at large. This is somewhat harder to prove than the above, but we can look at certain proxies. We know that MPs earn significantly more than the average national wage, for example. Another proxy of overall wealth might be property ownership. On this count, figures from early 2016 suggest that around a third of all MPs let property as landlords, this compared with only 2% of Britons as a whole. Education, particularly private or independent education can also be seen as a proxy of familial wealth in the form of a privileged upbringing. Following the 2015 General Election, the Sutton Trust found that 32% of MPs had been privately educated compared to just 7% of the UK population.

Moving from characteristics to attitudes, the political class has been accused of a profusion of sins ranging from Europhilia, elitism, and London-centrism. It’s tough to say how true any of this is—there is little reliable evidence as to the content of politicians’ attitudes. Primarily, this is because it is increasingly difficult for political scientists and other interested parties to survey them in any kind of reliably representative fashion. I also suspect it is because a fair few of those who make claims regarding their content are not always as interested in backing them up with evidence as they are in making them in the first place. Some, like Colin Hay and Owen Jones, have made convincing arguments about how the political class may largely share views about the economy, specifically a belief in the superiority of free-markets over government-managed mechanisms as well as the fact that some large areas of public policy are better handled when the “politics” is taken out of them. If true, this will not only reflect the composition of the political class in terms of personal characteristics, but also shape it.

Finally, others have focused their ire on the behaviour of the political class. Suffice it to say, literally none of these critics are saying how well-behaved they think our politicians are. One theme is that the political class, far from doing things that they actually believe in, will instead do whatever it takes to climb on to the next rung of the political career ladder. The suspicion here is that if someone has set themselves the goal of holding powerful political office, they are likely to do anything necessary to make it there and, as such, they probably will not make for the kind of politician who the public claim to want—someone who will stand up for the nebulous category of “what they believe in.” Others see them as behaving in such a way that prioritises their own personal gain, while others again feel they are bearing witness to a political class that continually behaves in a strange way. Barbara Ellen, writing about politicians’ behaviour asks, “Why can’t they just look more normal?”, while others leapt on Ed Miliband’s tussle with a bacon sandwich as further evidence that members of the political class were fundamentally odd compared to most Britons and seemed doomed to continue to behave in such a way. Again, however, it is hard to say anything especially certain about this charge—the diagnosis of weird behaviour is, undoubtedly, in the eye of the beholder.

So, there is some support for the various planks of the political class narrative, especially that relating to the lack of characteristic diversity within it. Regardless, however, of the broader veracity of the narrative, its potency is hard to deny and this raises difficult questions for those seeking to counter it.

Featured image credit: Parliament London England Sunset by Skeeze. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post Exactly what is our problem with the political class? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 16, 2018

Embracing the cattle

A story that keeps recycling the same episodes tends to become boring. So today I’ll say goodbye to my horned friends, though there is so much left that is of interest. In dealing with cows, bulls, bucks, and the rest, an etymologist is constantly made to choose among three possibilities: an ancient root with a transparent etymology (a rare case), a migratory word, or a sound-imitative formation. Like cattle breeders, words are nomads, but some are more sedentary than the others.

Here is a quotation from an excellent article on the origin of the Russian word for “bull”: “The various ancient and modern [Indo-European] languages show a well-developed and rather consistent terminology for cattle, sheep, goats, swine, and horses…. There are normally two terms for the male of the species: one for the castrated male, which is used for work or fattened for slaughter, and another for the breeding male, whose main duty is procreation. The majority of words for the breeding male refer in some way to his potency, and most of the rest refer to his strength, speed, or other ‘manly’ qualities. Not a single term for a breeding male animal is related in any way to the sound the animal makes, nor, with less than a half-dozen exceptions out of a very large number of names, is any name for any type of cattle, sheep, goats, swine, or horses onomatopoeic in origin.”

A yoke of oxen. This is how plowing began. Image credit: Bow yokes on a bullock team by Cgoodwin. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

A yoke of oxen. This is how plowing began. Image credit: Bow yokes on a bullock team by Cgoodwin. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.This is an important generalization, but, even if we disregard the idea of exceptions, it assumes that the etymology of the words we have before us is known, and the reasoning becomes partly circular. Also, the author’s parade example is bull, allegedly associated with swelling and balls (testicles), and we have seen that this venerable etymology is less dependable than it seems. I may add that the association between a testicle and a ball, so obvious to English speakers, is rare. Testicles are much more often thought of as eggs. In Germanic, only Dutch zaadbal “seed ball” is close to English. German has Hode, from “covering,” and Icelandic eista goes back to the idea of “egg.” The origin of Latin testiculis and its ties with the root of such words as testify (Latin testis “witness”) have been discussed for centuries. If, as mentioned last week, bull does mean “swollen,” this happens because the animal is huge, swells with rage, or whatever. Anyway, testicles don’t swell, the penis does, a detail demurely passed over in the traditional etymology, and the English speakers who called testicles balls did not know the Indo-European origin of the word phallus.

I will now make good on my promise and say something about the derivation of ox, the only English noun that has retained the ending of the old declension in the plural (-en in children has a different origin). The word is very old. It occurs in the Gothic translation of the New Testament (the fourth century), in Luke XIV: 19 (“I have bought five yoke of oxen”). The Greek text has boûs. In Classical Greek, the word meant “ox, cow” and “bull.” All the Germanic cognates are like Old Engl. oxa. The suggestions will now seem familiar and unexciting. The cognates are many, including a close analog in Sanskrit, so that perhaps the word has a solid Indo-European root. Such a root has been proposed: it means “to moisten,” or, by extension, possibly “to impregnate.” Predictably, one runs into Turkic ökür “ox,” and we find ourselves on familiar ground. Only two conclusions are irrefutable: ox is not a sound-imitative word, and, when it was coined, it did not mean “a castrated bull.”

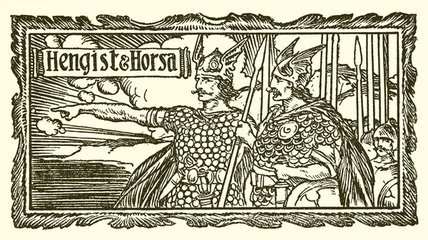

Such is the modern idea of the chieftains mentioned by the Venerable Bede. Image credit: Engraving depicting the brothers Hengist and Horsa, legendary leaders of the English invasion of Britain by Sir Edward Parrott. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Such is the modern idea of the chieftains mentioned by the Venerable Bede. Image credit: Engraving depicting the brothers Hengist and Horsa, legendary leaders of the English invasion of Britain by Sir Edward Parrott. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Before the curtain drops on this series, it may be useful to say something on some words for “cattle.” The oldest Germanic word is known from Gothic: it is faihu (ai has the value of e in Engl. echo). By the First Consonant Shift, faihu corresponds sound for sound to Latin pecu or pecus (the same meaning, and even the declension is the same; Germanic f and h derive from non-Germanic p and k). Dutch vee, German Vieh, and Icelandic fé are the reflexes (that is, continuations) of the same protoform. But the Gothic word meant “gold” and “movable goods.” The ancient equation “cattle” = “riches” is universal: those who possessed a lot of cattle were well-to-do, wealthy, rich. In the other Old Germanic languages, the cognates of faihu designated both “cattle” and “property; money.” Historical linguists discerned the root of pecus in Classical Greek pékein “I shear,” pókos “fleece,” and perhaps in Engl. fight (from feohtan), on the assumption that the Germanic verb meant “to pluck,” because at one time, wool was plucked, not shorn from sheep (see the post for October 25, 2017) and because “cattle” first meant “sheep.”

Medieval Latin capitale ~ captale “property” (vivum capitale “livestock, cattle,” literally, “so many head of cattle”) has reached English in three forms: cattle, chattel, and capital. The connection between cattle and money can also be noticed in the English words pecuniary, from Latin (Latin pecunia “money”: pecu ~ pecus “cattle,” see above) and, less obviously, peculiar, for Latin peculium meant “property in cattle, private property.” In English, peculiar turned up in the fifteenth century and passed through the stages “that is one’s own, particular” and then “uncommon, odd, specific.” The noun fee also belongs to our story. Originally, the word meant “estate in land on feudal tenure.” It emerged in Anglo-Norman and is cognate with pecu ~ pecus and the rest. Fief (feoff) and very probably feudal belong here too.

It follows that cattle is a borrowed word. The native word for horned animals has survived in Dutch (rund) and German (Rind). Both have an English congener (rother “ox”), but few people will remember it. In the past, all of them began with an h: Old Engl. hrūðeru, Old High German hrind, and so forth. The root (hr), here on the zero grade of ablaut, appears to be the same as in the word hor-n; if so, then the original sense of rother was “horned animals.” Probably hart “stag” (German Hirsch) has the same root; then again “a horned animal” (but herd is not related to hart). King Hrothgar, whose kingdom Beowulf rid of the monster Grendel and the monster’s mother, had a palace called Heorot “Hart.” Perhaps antlers graced it, but this is just a guess. Those curious about the ramifications of the root horn will remember from the post on cow that the Slavic word for “cow” is krava ~ korova, etc. Kr-, naturally, corresponds to Germanic hr– by the First Consonant Shift, which I’ll mention here for the last time.

Perhaps one day I’ll make a foray into the hornless animal world. Then we’ll meet Hengest (or Hengist) and Horsa, the legendary equine conquerors of ancient Britain.

This is probably what the famous mead hall once looked like. No longer impressive, but inside it must have been great. Image credit: Reconstruction of a viking house from the ring castle Fyrkat near Hobro, Denmark by Malene Thyssen. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

This is probably what the famous mead hall once looked like. No longer impressive, but inside it must have been great. Image credit: Reconstruction of a viking house from the ring castle Fyrkat near Hobro, Denmark by Malene Thyssen. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.TOWARD THE SPELLING CONGRESS, LONDON, MAY 30, 2018

Now that the Congress has been announced, many of our readers may be wondering how to reform our chaotic spelling. I don’t think all the inconsistencies of English orthography can be liquidated in one fell swoop. To gain public support, the reformers should, in my opinion, first suggest the measures against which even the most conservative opponents will be unable to offer any reasonable arguments. 1) Respell foreign and some native words with non-functional double (and even single) letters. Address, committee, and their likes; perhaps succumb and so forth. No one needs till, acknowledge, acquaint, and acclaim, to say nothing of chthonic. Change y to i in sphynx, syringe, stymied, and their likes. Almost all of them are Greek. We can certainly live even with sintax and sinthesis. English is not Greek. 2) Orthography is based not only on the phonic principle. Thus, it would be wonderful to remove k- in knife, but it should probably stay in know, to save its ties with acknowledge (aknowldge!). 3) I would like to repeat my main thesis. After more than a century of inaction, we should first strive for a political victory and try to persuade the public that something can and should be done. If we succeed in making this step, the rest will take care of itself (with patience and time).

Featured image credit: Reindeer pulling a sleigh on a farm in Russia by Elen Schurova. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Embracing the cattle appeared first on OUPblog.

May 15, 2018

America’s neglected conflict: The First World War

Ask an American what comes to mind about the First World War and the response is likely to be “not very much,” and certainly less than about World War II. Perhaps that is to be expected, given the different circumstances under which the United States entered the two wars. In 1941 the choice was inescapable after the searing experience of Pearl Harbor. But for years after the outbreak of war in Europe in 1914, the conviction remained widespread that American interests were not directly threatened by events an ocean away. Moreover, once the United States formally entered the conflict in April 1917, it fought for just eighteen months until the Armistice. In contrast, in the Second World War, American soldiers waged a much longer, geographically expansive, and costly four-year struggle in the European and Pacific theatres. The million-man American Expeditionary Force (AEF) mobilized to Europe in 1917-18 certainly eclipsed any previous American military effort, but itself was dwarfed by the 16 million troops in uniform in World War II. Casualties told a similar tale, as the 116,000 men lost in the First World War seemingly paled in comparison to the 405,000 troops who died in between 1941 and 1945.

The disparity in how Americans recall the two conflicts is also evident in stone. Although in the 1920s many cities and towns chose to erect monuments, plaques of honor roll, and cemetery memorials to their hometown heroes, there was until very recently no organized effort to create a national edifice to commemorate America’s participation in World War I. An impressive World War II memorial opened to the public in the spring of 2004 with a prominent location in the preeminent commemorative space of the National Mall in Washington, DC. The anticipated monument to American participation in the First World War will be less prominent, consigned to a nearby park currently honoring General John J Pershing, commander of the AEF.

Eclipsed by the second, bigger conflict, the First World War seems in danger of being America’s forgotten war. It deserves better. Its impact and significance merit our attention. This is true both for its specific effects in the United States and its broader reach as a global event. Americans experienced the vastly expanded administrative and regulatory authority of the federal government in matters ranging from conscription and tax policy, to the imposition of daylight saving time. Whether it was Doughboys overseas (or out of state) returning from their service abroad or economists grappling with reparations, Americans could no longer remain as isolated from world affairs. As a world war, its destructive legacy included the turmoil surrounding the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian, German, Ottoman, and Russian empires, the ensuing polarization between the Soviet state and the West, the dislocation of economies, and the diminished confidence in liberal governments or the prospect of progress. Not to mention the perhaps forty million soldiers and civilians killed or wounded during the conflict. A good case can be made that the First World War, not the advent of the year 1900, marks the real beginning of the twentieth century.

Eclipsed by the second, bigger conflict, the First World War seems in danger of being America’s forgotten war. It deserves better.

A good case can also be made as well that one of the most effective ways of grasping the impact of this war with its massive disruption, transnational significance, and huge, seemingly impersonal, scale is to put a human face upon it. A more intimate and revealing look at the conflict, through the varied experiences of individual participants, allies and enemies, combatants and civilians, prisoners and internees, is possible through the diaries they left behind. Those diaries, from the battlefields, the camps, and the home fronts, can offer us unique and compelling insights into that conflict.

These individuals did not intend to put their experiences to paper for a curious public to read a century later. On the contrary, the diaries were written for the purpose of reflection, consolation, and psychological relief—as a coping mechanism to deal with the realities of isolation and death, as well as a record for their families on the home front.

One of the most unique and compelling diaries is that of a young Jewish German business apprentice, Willy Wolff, who interned in an enemy alien camp for much of the war. That internment camps even existed before the Second World War is a lesser-known fact. Rapidly cobbled together British wartime legislation mandated the arrest and detention in camps of non-naturalized foreigners, especially, but not exclusively, those of military age from Germany and Austria-Hungary. Such laws were the product of an increasingly xenophobic and spy-obsessed nation.

The largest of such camps, Knockaloe, located on the windswept Isle of Man in the middle of the Irish Sea, housed 20,000 “enemy aliens” from 1915 until 1919, one of whom was Wolff. His diary, resurrected from an archive and translated for the first time into English, paints in great detail a depressing portrait of a man whose only offense was his German birth. Suffering from ennui, hunger, frustration, and resentment in captivity, Wolff describes in vivid detail camp conditions, including the strict regulations and punitive measures imposed upon internees, as well as the tensions that often surfaced between the internees themselves. Finally released in 1919, Wolff returned to his German homeland where he remained until the rise of Nazism forced him to immigrate to the United States. Somehow, however, Wolff never lost faith in humanity and his religion. His remarkable diary is a poignant reminder from a century ago of the vulnerable status of aliens and the dangers of rampant xenophobia.

The records of World War I diarists serve to underscore the importance of a war that for too long has been neglected.

Featured image credit: Pershing Park at 14th and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW in Washington, D.C. The park is named after John J. Pershing, the General of the Armies during World War I by AgnosticPreachersKid. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post America’s neglected conflict: The First World War appeared first on OUPblog.

Organic farming genetics and the future of food

What does the drug insulin have in common with cheese, Hawaiian papaya and a vegan burger? All were developed using genetic engineering, an approach established more than 40 years ago.

In the early 1970s, researchers in the San Francisco Bay Area demonstrated that it was possible to genetically engineer bacteria with a new trait. They showed that genes from different species could be cut and spliced together and that the new genes could be reproduced and expressed in the bacteria.

Human insulin, the first genetically engineered drug marketed (a human gene expressed in a microbe), has been used since 1982 for the treatment of diabetes, a disease affecting more than 9% of the US population. Genetically engineered insulin has replaced insulin produced by farm animals because of its lower cost and reduced allergenicity.

Cheese is made by coagulating milk with the addition of rennet to produce curds. The curds are separated from the liquid whey and then processed and matured to produce a wide variety of cheeses. The active ingredient of rennet is the enzyme chymosin. Until 1990, most rennet was produced from the stomachs of slaughtered newborn calves. Today, at a 10th of the 1990 cost, chymosin is produced through genetic engineering. Genetically engineered chymosin is distributed globally, with 80% to 90% of the hard cheeses in the United States and United Kingdom produced using genetically engineered chymosin.

Campaigns against genetically engineered crops reflect a general anxiety about plant genetics and a distrust of established institutions.

In the 1950s, the entire papaya production on the Island of Oahu was decimated by papaya ringspot virus, which causes ring spot symptoms on fruits and stunting of infected trees, creating a crisis for Hawaiian papaya farmers. In 1978, Dennis Gonsalves, a local Hawaiian, and his coworkers spliced a small snippet of DNA from a mild strain of the virus into the papaya genome. The genetically engineered papaya yielded 20 times more papaya than the non-genetically engineered variety when infected. By September 1999, 90% of the farmers had obtained genetically engineered papaya, and most had planted them.

Patrick Brown, founder of Impossible Foods, is building on advances in genetic engineering to shift the world’s population away from its reliance on meat, egg, and milk products. His team of researchers is isolating proteins and other nutrients from greens, potatoes, and grains to recreate the complex flavors of a hamburger. To give the burger the color and flavor of beef, the team decided to add leghemoglobin, a protein found in the root nodules of peas and other plants that form a symbiotic relationship with nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Leghemoglobin has close chemical and structural similarities to the hemoglobin found in animal blood, and, like hemoglobin, it is red. The team used genetic engineering to express the plant gene encoding leghemoglobin in yeast and added the isolated yeast-produced protein to the mix. When you bite this vegan burger, it oozes red.

Thirty-five years since the first genetically engineered medicine was commercialized and more than 20 years since the first genetically engineered crop was planted, applications of genetic engineering have proliferated. It has been used to engineer insect resistant corn and cotton, reducing the amount of chemical insecticides sprayed worldwide, created apples that do not brown easily and provided new tools to save the lives of impoverished children. During this time, there has not been a single verifiable case of harm to human health or the environment.

Every major scientific organization in the world has concluded the genetically engineered foods on the market are safe to eat . These are the same organizations that many of us trust when it comes to other important scientific issues such as climate change and the safety of vaccines.

Despite the record of safety and environmental benefits, the process of genetic engineering (often called “GMO”) still provokes controversy and sometimes, violent protests.

Campaigns against genetically engineered crops reflect a general anxiety about plant genetics and a distrust of established institutions. It is often difficult for consumers and policy makers to figure out how to differentiate high-quality scientific research from unsubstantiated rumors. Jim Holt, a writer for The New York Times Magazine, cites a survey indicating that less than 10% of adult Americans possess basic scientific literacy. For nonscientists, it may be the sheer difficulty of science and its remoteness from their daily activities “that make it seem alien and dangerous.”

It may be that improved access to science-based information on genetics, food, and farming can help consumers and policy makers make environmentally sound decisions. But cognitive science reveals that we are subjective about how we get our information, what we trust and believe, and how we feel about the facts we get. Feelings are an inescapable part of our perceptions, no matter how well informed we are.

So, how can we move forward? By the year 2100, the number of people on Earth is expected to increase to more than 11.2 billion people from the current 7.6 billion. If we don’t change eating habits or reduce food waste, we will need to produce more food in the next 50 years than we produced in the last 10,000 years . And we need to do this while minimizing environmental impacts.

According to David Ropeik, an expert on risk perception, “If we want to make the smartest possible choices, we need to challenge ourselves to go beyond what instinctively feels right and try to blend our feelings with a careful, thoughtful consideration of what might actually do us the most good.”

Featured Image Credit: “Papaya Fruit Cut In Half Cut Vitamins Eat” by Couleur. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Organic farming genetics and the future of food appeared first on OUPblog.

Playing Bach on the violin

Bach’s superlative works for violin are considered the pinnacle of achievement for any violinist. Both the unaccompanied Partitas and Sonatas and his violin works with keyboard accompaniment require great technical mastery of the instrument alongside a mature musicality. Players who haven’t yet scaled these heights are also keen to access his music and develop their understanding of Baroque playing techniques.

One way to do this is from carefully-written arrangements—playing original pieces from across Bach’s output that have been re-worked for violin and accompaniment at an intermediate level. Re-working music originally written for one set of forces for another instrumentation was common practice in the Baroque era, and there are many examples in the works of Handel, Vivaldi, and Bach. There is speculation that Bach’s famous organ work, the Toccata and Fugue in D minor, may have begun life as a violin piece. Such arrangements can include a range of technical and musical teaching points that provide an invaluable introduction to Baroque style.

Listen to J. S. Bach – Sinfonia in D major: BWV 789, originally for keyboard, which David and I arranged for violin for an earlier anthology.

Crisp and well-articulated bowing is a corner-stone of Baroque style; the two principal types are detaché and martelé — the first a neat detached style, and the second requiring a little more attack or bite (the literal meaning is “hammered”). Lively allegro movements will give ample opportunity to develop these forms of bowing. Faster semiquaver passages in Baroque music often require the player to slur three semiquavers and bow one separately, or indeed the other way around. Organizing their bowing so as not to travel too far towards one end of the bow is an essential skill for players to master.

In his cantata movements, Bach was adept at writing obbligato lines perfectly suited to his chosen instrument; there are many examples that exploit the singing tone of the violin, such as in the aria “Auch mit gedämpften, schwachen Stimmen” (“Also with muted weak voices [is God’s majesty honoured]”), from Cantata BWV 36. The violin line appears to be never-ending, and requires a great deal of stamina and good bow control to maintain an evenness of sound. It’s also a wonderful example of string-crossing technique—the right wrist needs to remain flexible throughout, and practising the string-crossing on open strings is useful for beginners.

Slower movements allow players to shape expressive sustained lines with long controlled bows, and a classic example amongst violin arrangements is the ever-popular Gounod/Bach Ave Maria. This is also an excellent piece to work on finding the right sound points for the bow: the higher passages and varied dynamics need careful planning for the bow in order to achieve the desired effect.

Image credit: Arrangement of Gounod’s “Ave Maria” (Meditation on the First Prelude by J. S. Bach) from Bach for Violin.

Image credit: Arrangement of Gounod’s “Ave Maria” (Meditation on the First Prelude by J. S. Bach) from Bach for Violin.In terms of left-hand technique, as the fingerboard was shorter on Baroque violins, much of the music goes no higher than third position, and players at the time often played a good deal in first position. However, arrangements of Baroque pieces, particularly those not originally written for string instruments, can provide opportunities to explore other positions that are often overlooked.

It’s fascinating to remember that, not only did the concept of equal temperament have no meaning in Bach’s time (his “well-tempered” tuning had some variation of the 5ths across the keyboard), but string players don’t necessarily conform to this system anyway! This realization, particularly in unaccompanied movements, offers the player the opportunity to consider aspects of intonation for colour and effect. Would slightly higher thirds in sharp keys brighten the sound and give extra brilliance? Would lower thirds in minor keys establish a darker sound?

Learning dance movements such as minuets and bourrées will build understanding of these forms, while an appreciation of their playing styles—emphasising the first beat of the bar and keeping the upbeats light—will add life and character to any performance. Performing pieces in arrangements for violin and keyboard offers players the chance to develop their ensemble skills, particularly in Bach’s more contrapuntal music where understanding the interplay between the instruments and matching articulation is an important strand of musicianship.

Bach’s music has been a staple for musicians for two centuries or more. Well-crafted arrangements allow this remarkable music to be explored by new groups of players while also teaching them many important aspects of technique and musicianship. It’s hoped such arrangements might also inspire players to continue their musical journey with this exceptional composer.

Featured image credit: Photo by Serge Ka via Shutterstock.

The post Playing Bach on the violin appeared first on OUPblog.

May 14, 2018

Five key underlying drivers of the opioid crisis

The War on Drugs got it wrong.

When President Nixon launched the “War on Drugs” in 1971, he framed the way we would view drug epidemics moving forward: as a moral issue. The “war” cast people struggling with addiction as criminals and degenerates to be dealt with by the criminal justice system. But law enforcement solutions have failed to curb addiction, and have further contributed to harming communities already experiencing deep levels of trauma, particularly communities of color. Criminal justice approaches, which often tear communities apart rather than strengthening them, are not the key element to solve this far-reaching epidemic, and punishing people suffering from addiction is counterproductive.

As our understanding of addiction changes, we must address the underlying causes.

The current opioid epidemic has helped to alter the “face” of addiction — with the focus now on white, rural America — and with this change the popular understanding of addiction is beginning to shift from one of intolerance and stigma to empathy and action. The idea that addiction is not a moral failing (as it was portrayed during the crack epidemic that plagued urban communities), but rather the result of underlying structural drivers that must be addressed, is starting to take root and shape policy.

We can prevent community trauma if we know what to protect against.

Years of over-prescribing opioids and declining conditions in communities suffering from loss of industry and social upheaval has created a perfect storm for opioid misuse and, sadly, overdose deaths, which have been increasing year after year. In Ohio alone, from 2013 to 2015, unintentional overdose deaths climbed from 84 in 2013 to 1,155 in 2015. In 2016, 11 people in that state died each day from opioid misuse. County health departments and the behavioral health sector have long worked on opioid misuse, but have often fallen short because their efforts almost exclusively focus on treatment, without addressing the underlying root causes of the epidemic.

Criminal justice approaches, which often tear communities apart rather than strengthening them, are not the key element to solve this far-reaching epidemic, and punishing people suffering from addiction is counterproductive.

The factors driving addiction overlap with factors driving community trauma.

Prevention Institute is using its community trauma approach to address opioid use disorder (OUD) in 12 communities in Ohio. The approach focuses on community factors by identifying drivers of addiction, which overlap with drivers of community trauma. Trauma can result from racism and discrimination, intergenerational poverty, lack of job opportunities, exposure to violence, substandard housing and education, and lack of access to key services. My colleague, Dana Fields-Johnson, talks about the importance of reframing the initial conversation from one that asks individuals “what did you do?” to one that asks “what happened to you, and what’s going on around you that has made you susceptible to substance misuse?” This shift is critical to finding solutions that stop the wave of deaths occurring, reduce stigma associated with misuse, and build community will and capacity for prevention of OUD. While each community is different, common drivers of trauma and opioid misuse include:

Loss of industry and living wage jobs – Loss of industry in rural areas has resulted from trade policies and other economic trends that have led many US manufacturing jobs to relocate overseas. Agricultural policies favor large agribusinesses, and have forced local and small family farms out of business. As a result, unemployment is high, health has declined, and communities are struggling economically.

Lack of economic opportunity and a pervasive sense of hopelessness – The economic decline in many rural areas means there are fewer opportunities for residents to obtain living-wage jobs and meet their basic household needs. Beyond that, these communities often lag behind in economic investment, which creates limited stable affordable housing, and fewer recreational opportunities, educational opportunities, and opportunities for artistic and cultural expression.

Broken relationships and frayed social connection – When economic and social opportunities disappear, often community members who can afford to relocate will move out of the area. This means that family and social support networks deteriorate, and those who remain can’t necessarily provide social support to others. Compounding the problem is the fact that the exodus of more affluent community members draws resources away from communities, contributing to a lack of public funding to build and maintain safe and welcoming public spaces.

Norms that keep the problem hidden from view – In many rural communities, people identify strongly with the idea of being “independent,” which can make people hesitant to seek help. In addition, because there is a shared understanding that substance misuse is a private issue, it’s more difficult for people to let others know about challenges they or their families face. Finally, in some communities, the opioid epidemic is so advanced that intergenerational use of opioids has become the norm.

Lack of access to care – Communities depend on state and federal funding for mental health services. State funding for local mental health facilities and services varies widely, and rural communities, which often have smaller tax bases, struggle to fund public health and prevention programs that address substance misuse. Exacerbating the issue is the lack of clinical professionals, and limited access to healthcare services available in rural communities.

The end goal: Grow stronger as a community

Prevention Institute’s approach to opioid misuse acknowledges that communities, not just individuals, have experienced trauma — and that addressing the sources of trauma is essential in any response to the opioid epidemic. Growing strong and resilient communities will also require more attention on preventing future addiction before it occurs.

Last year, through the 21st Century Cures Act, Ohio received substantial funding to address the opioid epidemic, with a portion of that being directed to assisting 12 prioritized counties developing prevention plans. The Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services is working with the 12 counties to broaden their efforts and take a closer look at community conditions and the systems that have a role to play in finding multi-sector solutions. Through a prevention and public health approach, which acknowledges and addresses community trauma whilst considering the elements in the community environment that are drivers of the epidemic, Ohio and other states disproportionately impacted by OUD and overdose deaths can get ahead of the opioid epidemic.

Featured image credit: “President Nixon, with edited transcripts of Nixon White House Tape conversations during broadcast of his address to the Nation” by National Archives & Records Administration. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Five key underlying drivers of the opioid crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers