Oxford University Press's Blog, page 257

May 5, 2018

John Tyndall in America

The development of the world, and of scientific discovery, is highly contingent on the actions of individual people. The Irish-born John Tyndall (c. 1822–93), controversial scientist, mountaineer, and public intellectual, nearly emigrated to America in his early 20s, like so many of his fellow countrymen. Had he done so, the trajectory of nineteenth-century scientific discovery would have been different. The histories of magnetism, glaciology, atmospheric science, bacteriology, and much more, would be altered. The Tyndall Effect and Tyndallization would be unknown terms. There would be no Mount Tyndalls in the Sierra Nevada or Tasmania, no Tyndall glaciers in Colorado, Alaska, or Chile, and no Tyndall craters on the Moon or Mars. The Pic Tyndall, on the Matterhorn, would carry another name. The Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research in Norwich, England, and the Tyndall National Institute in Cork, Ireland, if they existed, would have different names.

In 1844, the young John Tyndall planned to sail on the Thomas P Cope out of Liverpool, to join friends and relatives in Ohio, and to seek work as a draughtsman or surveyor. That he did not go was due to the last-minute possibility of bidding for a surveying contract in Ireland. Though he was unsuccessful, the moment had passed.

Tyndall is one of the fascinating and intriguing figures of the nineteenth century. An outspoken physicist and mountaineer, who rose from a humble background to move in the highest reaches of Victorian science and society, and marry into the aristocracy, his story central to the development of science and its place in cultural discourse. He was one of the most visible public intellectuals of his time, bridging the scientific and literary worlds.

He was one of the most visible public intellectuals of his time, bridging the scientific and literary worlds.

In scientific circles, he is best known for his research on the absorption of heat by gases in the atmosphere. Through this work, he set the foundation for our understanding of climate change, weather, and meteorology. Among much else, he explained why the sky is blue, how glaciers move, and helped establish the germ theory of disease.

Beyond that, he was a pivotal figure in placing science on the cultural and educational map in mid-century, and in negotiating its ever problematic relationship to religion and theology. His iconoclastic speeches and writings sent shockwaves through society, not least in religious circles. With friends such as Michael Faraday, Thomas Huxley, Charles Darwin, Rudolf Clausius, Hermann Helmholtz, Emil du Bois-Reymond, Thomas Carlyle, and Alfred Tennyson, he was at the heart of nineteenth century thought.

In the event, Tyndall did visit America, but not until 1872, when—as one of the most prominent scientists and public figures of his time—he made a famous lecture tour, formally instigated by Joseph Henry, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Stellar figures like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Louis Agassiz added their names to the invitation. The tour took in six American cities: Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington (where President Grant himself attended), New York, Brooklyn and Newhaven. Interest and demand was high in all the venues, and Tyndall’s lecturing and demonstration style was a revelation.

Tyndall was well-known in America, even before his visit, through his popular writings, covering science, mountaineering, and the boundaries between science and religion. Indeed, his reputation was such that he found himself better known in Philadelphia than in many English cities. Demand for reprints of his lectures—a series of six on the theme of Light—was huge. Printed by the New York Daily Tribune, some 300,000 were sold across America.

Tyndall came to America determined to give the Americans a piece of his mind. He used the lectures, about the fundamental physics of light, to convey a broader message about the need to support scientific research for its own sake, untrammelled by demands for immediate application. In his view, the Americans were neglecting this vital element, and were instead drawing their ‘intellectual treasury’ from England.

To his credit, Tyndall put his money where his mouth was. He had determined that he would make no personal profit from the American visit. Instead, having published his full accounts, he invested the surplus of $13,033.34 to set up a fund that his cousin Hector Tyndale (a Brigadier-general in the recent Civil War) referred to as the Tyndall Trust for Original Investigation. The investment flourished, and in 1884 Tyndall decided to divide the sum equally between Columbia College, Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania, creating three Tyndall Fellowships. The scholarships ran for several decades, and until the 1960s in the case of Harvard, but no longer appear to exist.

Featured image credit: Professor Tyndall lecturing at the Royal Institution courtesy of the Royal Institution of Great Britain.

The post John Tyndall in America appeared first on OUPblog.

Karl Marx: 200 years on

This May, the OUP Philosophy team honors Karl Marx (1818-1883) as their Philosopher of the Month. 5 May 2018 marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of this revolutionary philosopher who is best known for The Communist Manifesto and Das Kapital, and the substantive theories he formulated on the capitalist mode of production, communism, and class struggles after the dawn of modernity.

Marx believed that the development of modern capitalism had an impact on social formations in a profound way, turning the relations between individuals into one of mutual exploitation and alienation. Mark’s radical belief in the inevitability of communism was articulated in the famously striking opening sentence of The Communist Manifesto: “A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of communism.’’ He saw that the working class could be agents of change.

Despite the shortcomings of his theories, Marx’s critique of modern society reverberates and remains relevant even in the twenty-first century. Understand why with our slideshow below on the life, legacy, and influence of Karl Marx.

Featured image: Berlin, Unter den Linden, Victoria Hotel between 1890 and 1905 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Karl Marx: 200 years on appeared first on OUPblog.

May 4, 2018

How do male hummingbird dance moves alter their appearance?

Many animals use colorful ornaments and exaggerated dances or displays to attract mates, such as birds of paradise. Some animals go even further and have colors that can change as they dance, such as in peacocks or morpho butterflies. This special type of color is called iridescence, and its appearance changes based on the angles of observation and illumination. Thus, the appearance of iridescent coloration can be easily manipulated by specific movements, postures, and orientations to potentially exhibit a lot of changes in color appearance during a particular dance—in other words iridescent coloration can produce a flashy color display.

Hummingbirds are incredibly fast-moving birds that exhibit a dazzling array of iridescent coloration. Some hummingbirds, in a group called bee hummingbirds (which includes many US species like the ruby-throated or Anna’s hummingbirds) also court females using a special dance called the shuttle display. Shuttles are characterized by a male repeatedly and rapidly flying back and forth in front of a female and erecting his colorful throat feathers to show them all to the female.

Image credit: Male broad-tailed hummingbird by Richard Simpson.

Image credit: Male broad-tailed hummingbird by Richard Simpson.We set out to understand 1) what male broad-tailed hummingbirds (Selasphorus platycercus) look like to females as the males dance, and 2) what might drive the variation in what males look like as they dance, such as their individual dance moves or how they position themselves with regards to the sun. To answer these questions, we filmed male courtship displays using a female in a cage to elicit male dances. We then measured several characteristics of the dances, such as how the male oriented himself towards the female as he moved, the shape and width of the back-and-forth movements, and how the male display was positioned relative to the sun. Then, we captured the males we filmed and plucked some of their iridescent feathers to measure male color appearance. To quantify male color appearance, we took the male feathers and moved them as if they were that male dancing, using his specific positions and orientations, and at each position in the display, we measured the color of the feathers.

We first asked: do males orient themselves towards the sun in a specific way, for example, do males always dance facing the sun? We found that males dance oriented toward the sun in many ways—some facing the sun, some facing away from the sun, and some in between.

We then asked: how might male orientation towards the sun affect his color appearance and variation in color appearance among other males? It turns out that those males who tended to face the sun while dancing appeared brighter, more colorful, and flashier. On the other hand, those males who tended to face away from the sun appeared darker and less colorful, but maintained a consistent color appearance as they displayed. Another way to think about hummingbird dances and color appearance is to compare it to when people dance in sequin clothing. If someone were to dance in a sequin outfit while facing a bright stage light, they would appear brighter, more colorful, and flashier, while someone who danced with their back to the stage light would appear darker, less colorful, but have a consistent color appearance.

Additionally, we found that males who maintained a persistent angle of orientation towards the female while dancing appeared flashier, and males with bigger colorful throat patches exhibited little changes in color appearance throughout their displays—in other words they were consistently colored. Back to the sequin dancer analogy, if the dancer was always facing you in the same way, they would appear flashier. We believe this flashiness is because if the dancer is keeping a relatively fixed angle of orientation towards you as she/he moves, then her/his angle towards the light is constantly changing.

Image credit: Female broad-tailed hummingbird on her nest by Richard Simpson.

Image credit: Female broad-tailed hummingbird on her nest by Richard Simpson.While we do not currently know if females prefer flashier colored males or more consistently colored males, recent work by Dakin and colleagues has shown in peacocks that the flashier males had higher reproductive success. It is also possible that some broad-tailed females prefer flashier males, while others prefer more consistent males. Flashy coloration might be better at demonstrating a male’s dance moves, while consistent coloration might be better for showing off how big a male’s color patch is. Future work is needed to test these ideas; however, our study begs the question: would you rather be flashy or consistent?

Featured image credit: Hummingbird landing on pink flower with green stem by Andrea Reiman. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post How do male hummingbird dance moves alter their appearance? appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten reasons to write in plain English [excerpt]

Medical science writing is important and writing in plain English (that being writing that conveys the right content, clearly, and concisely) is a skill honed by practice. Learning to express complex ideas succinctly is in no way a remedial skill. Rather, it can only be seen as a sign of mastery. This matters in the 21st century, as English is the global language of science. English-language medical journals contain discoveries from doctors and other medical scientists from around the world, who, although experts in their respective fields, may not be fluent in English. Thus, it makes sense to write about complex science without using complex grammar.

Good writing takes work. If your article is good enough to get published, why should you make an extra effort to ensure it is clear, concise, and readable? Below are ten reasons, excerpted from Plain English for Doctors and Other Medical Scientists.

1. It helps spread new medical knowledge

When doctors share ideas about theory and practice, it helps the spread of medical knowledge. New medical discoveries prevent illness, relieve suffering, find cures, and extend life. Difficult-to-understand writing slows down this process; clear, concise writing speeds it up.

2. It helps to teach the profession

The Hippocratic Oath is a tradition of the medical profession; many doctors take it when they graduate from medical school. As part of the oath, they pledge to teach others the profession ‘according to their ability and judgement’. This implies that they’ll do what they can to make medicine understandable to others.

3. It shows respect for the reader

Doctors are busy professionals. When you write in plain English, it shows respect. Your reader will read faster, understand the information better, and remember it longer. Research in other fields shows that 80% of readers prefer to read plain English. Even if they can understand an article written in a traditional style, doctors are human too. Their brains work in the same way as everybody else’s. The same factors that influence reading ease for everybody else also influence reading ease for doctors.

4. It saves reading time

Research published in the Journal of the Medical Library Association reports that the average paediatrician spends 118 hours a year reading medical journals.

Writing expert Robert Eagleston thinks that writing in plain English may cut reading time by 30% to 50%. Joseph Kimble tested traditional and plain English contracts on various groups of readers and found that plain English cut reading time between 4.7% to 19.7% whilst also improving comprehension. Considering how much doctors read and how much time plain English saves, it seems likely that, if all medical journals were written in plain English, it could save the average doctor a week or two per year.

5. It helps your work reach the widest reasonable audience

When you consider the widest reasonable audience, and write in a style suitable for them, it promotes free and efficient exchange of new medical knowledge. Ideally, a medical journal article should be accessible to anybody interested in the subject matter, whether or not they are an insider in the field. This may include a doctor or scientist working in the same or related specialty, a student, or a nurse. It includes regular journal subscribers and those who search for articles on the internet.

English is the global language of science, but many people who read English-language medical journals are not native speakers. In fact, according to English-language expert David Chrystal, non-native English speakers outnumber native speakers 3:1.

6. It helps plead for a cause

Medical science articles advocate for people who are poor, sick, or oppressed. If you don’t make your point clearly, you’re not helping anybody. Writing in an inflated formal style sends the message that there’s no urgent problem. It’s just business as usual for those of us who work in a hospital, university, or research center. Writing in plain English helps to send the message that a problem is important and urgent.

7. It helps humanize your writing

Writing in plain English sounds more natural, closer to the way people speak in everyday life. It sounds professional, with careful attention to the science, but less formal and bureaucratic. This means that your writing sounds more human and puts less of a burden on your reader.

8. It shows respect for your work

Your research and ideas deserve to be presented clearly and concisely. Good writing helps build your reputation and benefits your career. More people will read your work and want to work with you.

9. It helps overcome editorial blindness

Writing in plain English helps you overcome editorial blindness, that feeling you get when you work on an article so long you miss problems that a reader with a fresh eye would see.

10. It saves time and improves content

As a medical researcher, your time is valuable. Learning to write and revise in plain English may take some extra time and effort initially; but, once you learn how to do it, it saves time for everybody. So ultimately, there is no extra cost.

Featured image credit: ‘Sign Here’ by Helloquence. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Ten reasons to write in plain English [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

May 3, 2018

Creativity, the brain, and society

Creativity research has come of age. Today, the nature of the creative process is investigated with every tool of modern cognitive neuroscience: neuroimaging, genetics, computational modeling, among them. Yet the brain mechanisms of creativity remain a mystery and the studies of the brains of “creative” individuals have so far failed to produce conclusive results.

But the mystery is gradually yielding ground. As we are reconceptualizing creativity as a complex, and arguably derivative construct consisting of many moving parts, we are beginning to study these moving parts in a systematic way. The old tabloid clichés linking creativity to specific brain structures are no longer tenable, but they do seem to have captured some important aspects of the underlying neurobiological processes. We no longer believe that creativity “resides” in the right hemisphere, but evidence is growing that the right hemisphere is particularly adept at dealing with novelty, an important ingredient of any creative process. In contrast, the left hemisphere appears to be the repository of well-entrenched knowledge and skills, verbal and non-verbal alike, which is an equally important prerequisite of a creative process (remember the giants on whose shoulders we all stand).

This is a radical departure from the old notion linking the left hemisphere to language and right hemisphere to non-verbal visuo-spatial processes, and it elucidates the complementary roles of the two cerebral hemispheres in the creative process. Furthermore, the complementary roles of the two hemispheres in supporting novelty vs well-routinized cognitive skills appears to be present across a wide range of species, not just primates, but other mammalians. They are present even in species whose brains are devoid of developed cortex and rely instead on the phylogenetically ancient principle consisting of relatively “modular” nuclei, such as birds (and by extension probably in dinosaurs). Such evolutionary continuities open the door for the studies of the evolutionary precursors for forebears of human creativity. Likewise, it is no longer tenable to view the frontal lobes as the “seat” of creativity, but evidence is growing in linking the frontal lobes to processing cognitive novelty. The frontal lobes, or, more precisely, the prefrontal cortex, is also critical for salience judgment, the ability to decide what is important and what is not. This ability is essential for the creative process, lest the creative mind strays into innovative but inconsequential esoterica.

We no longer believe that creativity “resides” in the right hemisphere, but evidence is growing that the right hemisphere is particularly adept at dealing with novelty, an important ingredient of any creative process.

But understanding the workings of the mind behind the innovation is only part of the challenge facing creativity research. In a society infused with innovation at an increasingly accelerating rate, understanding its impact on the consumer becomes particularly important. In the not-so-distant past, a human being could acquire a repertoire of knowledge and skills in one’s youth and coast on that knowledge for the rest of one’s life. This was true even for professionals engaged in seemingly daunting intellectual activities. In reality, however, a physician or an engineer could operate throughout much of their professional career on a “mental autopilot,” without much need to update their professional knowledge or skills. This was even more the case for a person’s ability to navigate daily life.

But today new technologies and knowledge saturate society at such a rate, that even the laziest and least intellectually inclined among us are forced to absorb innovation all the time, whether we like it or not, both in our professional activities and in everyday life. The ever-accelerating rate of innovation places unprecedented demands on its consumer and makes the consumer a real partner in the process to a degree unprecedented in the history of our species. When you see an octogenarian using an iPhone or an iPad, you can safely assume that she did not grow up with either of these hi-tech devices, that nothing in her early background prepared her for the flood of new electronic technologies, yet here she is, operating them confidently and competently. How does the human brain function in this new environment? How does it develop and how does it age? How do these radical changes in the degree of novelty exposure change the nature of psychiatric and neurological disorders, such as dementia?

Finally, in our increasingly technological world, the question of Artificially Intelligent (AI) creativity inevitably arises. Offensive as this may sound to the more exceptionalism-mined members of our own species, if creativity is defined as a conjunction of novelty and societal relevance, then the authorship of the creative process should not be part of its definition. Until now, AI has focused on the design of dedicated devices each adept at performing a pre-specified, relatively narrow class of task. But more recently the Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) movement is gathering speed with an audacious goal of designing artificial devices capable of open-ended learning and yes, creative processes. Today, AI-generated art, both paintings and music, has been judged by human connoisseurs as “creative.” How we, the biological humans, will fit into this brave new world and how we’ll be changed by it, is yet another question for future creativity research.

Featured image credit: Child painting by EvgeniT. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Creativity, the brain, and society appeared first on OUPblog.

A step in the light direction for arrhythmia

Each successful beat of the heart is the result of a well-timed electrical orchestra, headed by a conductor tasked with tirelessly maintaining this life-sustaining rhythm. The conductor of this silent symphony is the heart’s natural pacemaker cells, which synchronize the muscular contractions necessary to pump blood throughout the body.

Cardiac rhythm was described as early as 2,500 years ago in the writings of Chinese physician of legend, Bian Que. Similarly, the influence of electricity on heart rhythm is by no means recent knowledge. When this rhythm becomes irregular, that is to say, the orchestra ceases to follow the conductor, it is known as arrhythmia. A common example of this is atrial fibrillation, or AF, which affects in excess of 33.5 million patients worldwide manifesting as an abnormally fast, erratic heartbeat. Individuals may experience chest pain, feeling lightheaded, shortness of breath, or indeed, nothing at all. Over time, AF can contribute to heart failure, stroke, dementia and ultimately premature death. It is not surprising that research into new treatment approaches are a billion-dollar, ever-growing industry.

As is often the case in medicine, management of AF is a balance of curative versus intolerable or damaging effects.

Electronic defibrillators, first conceived over 50 years ago, have been a marked success in restoring normal cardiac rhythm when it goes awry. The device is a truly life-saving technological leap forward.

Unfortunately, by way of their operation, such devices deliver an electrical shock that can often cause considerable pain and distress to the user. In addition, the need for physical wires to transmit this shock is subject to anatomical limitations in their placement and albeit rare, the very serious risks surrounding wire extraction and infection. Given such disadvantages, new therapies for AF are being actively pursued.

Enter light: the familiar ally of the medical professional, with applications from radiation therapy to medical imaging, and now illuminating a possible route to modulate cardiac rhythm in conditions like AF without the difficulties of an implantable defibrillator.

In the past decade, a technique known as “optogenetics” has emerged onto the biological scene as part of the life sciences toolkit. Optogenetics has enabled researchers to sensitize specific cells to light in order to trigger various responses. To do so, a special class of light-sensitive proteins called opsins are utilized, which are normally found in photosensitive algae and the eyes of animals.

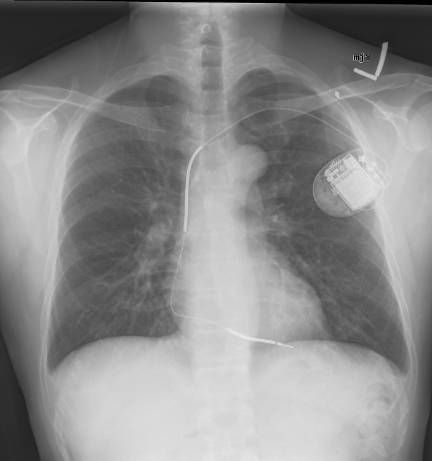

Image credit: A normal chest X-ray after placement of an ICD, showing the ICD generator in the upper left chest and the ICD lead in the right ventricle of the heart. Note the 2 opaque coils along the ICD lead via Gregory Marcus, MD, MAS, FACC. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: A normal chest X-ray after placement of an ICD, showing the ICD generator in the upper left chest and the ICD lead in the right ventricle of the heart. Note the 2 opaque coils along the ICD lead via Gregory Marcus, MD, MAS, FACC. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.In neuroscience, where the technique originated, optogenetics has greatly enhanced the investigation of brain function and connectivity. For example, it is now possible to activate specific clusters of neurons within the amygdalae of mice in response to light, setting off a fear response. The benefits of optogenetics for treating AF and other cardiac arrhythmias are easy to imagine; by sensitizing heart muscle cells to respond to a particular wavelength of light, light takes the place of the electric shock used by defibrillators to restore an irregular rhythm. In this way, light becomes the conductor of the cardiac rhythm. This has the potential to offer painless, sustained correction of arrhythmias in a more evenly spread manner compared to the focal points of an electric wire.

Researchers tested the viability of an optogenetics-based treatment for AF in mice whose heart muscles were poised to contract in response to blue light. After delivering the special light-sensitive proteins to the hearts of mice at risk for AF using gene therapy, the authors could reliably correct arrhythmias at the flick of a switch by applying high-intensity pulses of blue light directly to the heart. The authors proposed that this worked by holding the heart muscle cells in a kind of stasis, thereby preventing them from contracting to the irregular rhythm. Once the burst of light ceases, cardiac rhythm has an opportunity to resynchronize. Should this be the case, the long-term implications on heart muscle function remain to be seen.

Looking forward, a light-based strategy to fight arrhythmia might change treatment plans for the millions suffering from conditions like AF. Future studies in large animals more similar to humans should assess the safety and efficacy of delivering these special light-sensitive proteins – by gene therapy or otherwise. What is clear from this early work is that the necessary elements for a pain-free, light-based defibrillator are feasible and may provide a light at the end of the tunnel for AF research.

Featured Image Credit: “Pulse Trace Healthcare Medicine Heartbeat” by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post A step in the light direction for arrhythmia appeared first on OUPblog.

May 2, 2018

An interdisciplinary view of cows and bulls. Part 1: cow

When people began to domesticate the cow, what could or would they have called the animal? Ideally, a moo. This is what children do when they, Adam-like, begin to invent names for the objects around them. However, the Old English for “cow” was cū, that is, coo, if we write it the modern way, not mū. Obviously, cows don’t say coo. Pigeons do. Therefore, we are obliged to treat this word in the traditional way, that is, to look for the cognates, reconstruct the most ancient form, and so on. German has Kuh, pronounced very much like Engl. coo, and the same is, in principle, true of Dutch koe, except that the vowel is much shorter. They differ from Engl. cow, because in the remote past, they sounded as kō, not as kū. The Old Norse word was close to the Old English one. Thus, the first conclusion we should make is that the Common Germanic form for “cow” did not exist: the differences were small but apparent.

Once we leave Germanic, but, as long as we keep looking for monosyllabic words, we run into Latin bōs (genitive bōvis; familiar to English speakers from bovine “ox-like”) and Classical Greek boûs. Yet the meanings are partly unexpected: in both languages the words mean “bull, ox; cow,” though more often “cattle.” Especially interesting is the Latvian form, namely, gvos “cow” (dictionaries usually cite gùovs). There is of course no certainty that an ancient Indo-European word for “cow” existed, but, if it did, we note that Germanic has initial k, Greek and Latin had b, while Latvian gvos begins with gv. Germanic was subject to the so-called First Consonant Shift. For instance, for Latin duo English has two. Likewise, Latin gelu “frost” (compare Engl. gelid, and Italian gelata “ice cream”) corresponds to Engl. cold, German kalt, and so forth. It is the g ~ k correspondence that interests us here. Surprisingly, the Latin and Greek words for cattle begin with b, rather than g. And that is why Latvian gvos is so important. If we assume that the protoform began with gv– or rather gw-, everything falls into place. (I am leaving out some minor complications.)

A holy cow. Image credit: Mahabharata by Ramanarayanadatta astri. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A holy cow. Image credit: Mahabharata by Ramanarayanadatta astri. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Long ago, language historians suggested that some ancient Indo-European words began with gw, usually written as gw in our textbooks. This reconstructed but probably very real gw changed to Germanic kw, as expected (a sound easy to pronounce: English has it in quick, quack, quest, quote, quondam, etc.). Now, while pronouncing w, we protrude the lips, and, if the next vowel also requires labialization, to use a special term, this w may be lost. It does not have to be lost (compare quote and quondam!), but in no English word do we find kwu– ~ kwoo-. The Germanic name of the cow must have begun with kwō- or kwū-. Surprisingly, when the ancient group gw– occurred in Greek and Latin, not the w element but the first one (g) was lost, while w was even reinforced and became b (hence bōs and others). When we look up cow or its Germanic cognates in detailed etymological dictionaries, we find the protoform gwōu- translated as “cattle.”

Do we then have to assume that “cow” is not our word’s original meaning? Before we can answer this question, one more digression is needed. Even though the complex gwou (never mind the diacritics and tiny letters) and its reflexes (continuations) with initial b– are quite unlike the expected moo, perhaps they too resemble the sound made by a cow or a bull. Is then our animal name onomatopoeic (a sound–imitative word)? After all, moo is not exactly what the cow “says” (however, mu- and its variants are indeed the preferred verbs for mooing all over the linguistic map). I think the only animal “word” that people perceive in the same way in the whole world is meow ~ miaow. Other than that, compare bow-wow, barf-barf, ruff-ruff, and arf-arf, used to render the noise made by the dog. In Russian, dogs “say” gav-gav (almost the same in Spanish) and tiaf-tiaf. The English word to low has nothing to do with mooing. In the past, it began with hl-, which (once again!) corresponds to non-Germanic kl-, as in Latin clāmare “to shout.” It is anyone’s guess whether the root klā– is sound imitative and belongs with Engl. call, Russian golos and Hebrew qol “voice,” and many others. Thus, the onomatopoeic origin of cow is not impossible.

Vermeer, The Milkmaid and Ecce Homo, Caravaggio. Image credits: (Left) The Milkmaid by Johannes Vermeer. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (Right) Ecce Homo by Caravaggio. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Vermeer, The Milkmaid and Ecce Homo, Caravaggio. Image credits: (Left) The Milkmaid by Johannes Vermeer. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (Right) Ecce Homo by Caravaggio. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.If the Indo-European word for the cow was gwōu-, what do we do with Latin vacca, from which Spanish has vaca, French has vache, and so on? No trickery can connect vacca with cow, and this circumstance teaches us an important lesson. A language may have an old, inherited word and replace it with another. The origin of vacca is obscure despite the existence of a similar word in Sanskrit; the old comparison with Engl. ox, the animal name with cognates everywhere in Germanic, is certainly wrong. The double letter in the middle of vacca denoted a long consonant (a long consonant is called a geminate; remember the constellation Gemini?). Geminates in the root occurred most rarely in Latin (ecce, as in ecce homo “behold the man,” consists of two morphemes: ec–ce), but in many languages, they are typical of expressive and pet names. Probably vacca was one of such words.

As long as we stay in the Romance territory, we may remember that Italian has not only vacca but also mucca, seemingly a blend of mu– and vacca—an ideal coinage. Too bad, we don’t have Engl. mow, rhyming with cow and meaning the same. Also the Slavs had the Indo-European word for “cow” but substituted karva- for it. Its root is kar-, as in Latin cervus “deer,” related to English (and Germanic) hor-n, with h corresponding to non-Germanic k by the self-same First Consonant Shift. There is an opinion that the Slavic word was borrowed from Celtic, but details need not concern us here. The word must have meant “cattle,” and this is the sense we have observed in Greek and Latin. The sense “cow” is the result of later specialization, dependent on the progress of economy. The first animal people domesticated was the sheep. The cow was the second, and in this process, very much depended on whether cows were used for meat or for milk (judging by my experience, no one remembers the English phrase milch cow “dairy cow”; even the spellchecker does not know milch). With the specialization of the cattle’s functions, new words appeared. As long as nouns had three genders, the name of the female (cow), naturally, became feminine, while bull became masculine. Later, all kinds of words like heifer sprang up. We can now answer with certainty that “cow” was not the word’s original meaning

Is this the kingdom from which the name of the cow wandered east and west? Image credit: Upper part of a gypsum statue of a Sumerian woman. The hands are folds in worship. The eyes would have been inlaid. A sheepskin garment is wrapped on the left shoulder. Early Dynastic Period, c. 2400 BCE. From Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. The British Museum, London, by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP (Glasg). CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Is this the kingdom from which the name of the cow wandered east and west? Image credit: Upper part of a gypsum statue of a Sumerian woman. The hands are folds in worship. The eyes would have been inlaid. A sheepskin garment is wrapped on the left shoulder. Early Dynastic Period, c. 2400 BCE. From Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. The British Museum, London, by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP (Glasg). CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.There’s the rub we say, imitating Hamlet. Etymology is full of rubs. We have wandered over the map of the Indo-European languages, but the world is wide, and the ancient Indo-Europeans, nomadic or seminomadic, had contacts with the speakers of other language families. It turns out that the Sumerians had a similar word for “cow,” and so did the Chinese. Could it be a so-called migratory word? Yes, it could: there are many such. Everything depends on where people began to use cows for milk. Their neighbors might learn the art and borrow the word, which would “migrate” from one end of the earth to the other. We’ll never know. Such is the result of trying to take the cow by its horns. In any case, think global.

Featured Image: This is the constellation Gemini. While looking for or at it, think of geminates. Featured Image Credit: Abbaye St Philibert à Tournus – Mosaïque du déambulatoire by D Villafruela. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post An interdisciplinary view of cows and bulls. Part 1: cow appeared first on OUPblog.

Do government officials discriminate?

Suppose you write an email to a school district or a library asking for information about enrolling your child to the school or becoming a library member. Do you expect to receive a reply? And do you expect this reply to be cordial, for instance including some form of salutation?

It turns out that the answers to the two questions above depend on what your name is and on what it embodies. In a field experiment whereby we send emails signed by fictitious male senders to almost 20,000 local public services in the US, we document that requests of information sent by “Jake Mueller” or “Greg Walsh” received a response in 72% of the cases, with around three quarters of these responses being cordial. Identical requests sent by “DeShawn Jackson” and “Tyrone Washington” – two distinctively African-American names – receive instead a response only in 68% of the cases, with only around two thirds being cordial.

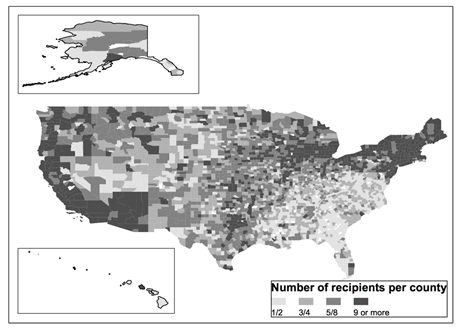

Figure1. Location of recipients. White fill indicates counties with no recipients. Provided by the authors and used with permission.

Figure1. Location of recipients. White fill indicates counties with no recipients. Provided by the authors and used with permission.The different responsiveness to “black names” as opposed to “white names” is present in all macro-regions of the US (North-East, Mid-West, South, and West). The gap is particularly sizeable for sheriffs (with a 7% points lower response for “black names” compared to 53% response rate for “white names”) but is also present for school districts and libraries. For county treasurers there is a sizeable difference, albeit not statistically significant, while for services with a smaller sample size (job centres and county clerks) we do not find evidence of differential treatment.

How to interpret these differences? Are they truly the result of racial discrimination? We use several approaches to address this point and exclude what is usually labelled as “statistical discrimination”. This type of discrimination could arise in our context if, for instance, public services were less prone to interact with people from a low social background and would use race to infer the socio-economic status of the sender. If this type of discrimination were present, for example, the recipient could attribute a higher socio-economic status to Jake Mueller than to DeShawn Jackson, because in general white people are wealthier than black people. This, admittedly, would not be commendable behaviour from public services but would be distinct from racial discrimination.

Several pieces of evidence point to the fact that what we document has to do with racial prejudice. First of all, we show that the difference in response between white and black senders is smaller in counties where the share of African-Americans among employees in the public sector is higher. The same pattern is observed when the recipient has a surname that is typically African-American. Moreover, in a second wave of emails, we add information about the socio-economic background of the sender by adding the sender’s occupation (real estate agent) below his signature. The fact that the gap in responsiveness in the second wave is identical to the first wave suggests that it is not attributable to the socio-economic status that the name might signal, but rather to racial discrimination. We also find that the differential response rate is positively correlated with other measures of racism used in previous studies, such as the prejudice index of Charles and Guryan (based on answers to questions on racial prejudice in the General Social Survey), the racially charged search rate of Stephens-Davidowitz (based on Google search data), and the race implicit association test created within the Harvard Project Implicit.

That requests of information coming from African-Americans are more likely to be ignored is not simply a nuisance, as there is growing evidence showing, for example, that citizens who are more informed about a certain public service are more likely to access or make use of that service. Moreover, the medical and psychological literature documents the physical and mental health effects of so-called racial micro-aggressions, that is, subtle everyday experiences of racism. For instance, the cumulative experience of derogatory racial slights can give rise to anxiety or diminished self-esteem.

How to solve this issue? Explicit discrimination by public service providers is is already illegal, so there is no quick legislative fix available. Recruitment practices may play a role, given our finding that discrimination disappears as recipients become more likely to be African-Americans. If what we find is due to an implicit – and possibly unconscious – bias, then making public officials aware of it may go some way in addressing the problem. In this case, academic studies, like ours and the media attention that they often attract, may be part of the solution.

Feature image credit: Statue of Liberty New York by BruceEmmerling. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Do government officials discriminate? appeared first on OUPblog.

The art of secular dying

When Stephen Hawking died recently, a report echoed around the internet that he had rejected atheism in his last hours and turned to God. The story was utterly false; Hawking experienced no such deathbed conversion. Similar spurious accounts circulated after the deaths of other notoriously secular figures, including Christopher Hitchens and, back in the day, Charles Darwin.

It’s pretty clear what lies behind these fabrications. Many people with religious faith have a hard time understanding how secular souls can find peace in the face of death. What might an unbeliever possibly find that could be as comforting as the prospect of a blissful afterlife? Wouldn’t their distress naturally lead the godless to faith? And, of course, there have been genuine instances of deathbed conversions—whether the result of grace, inspiration, or just a last-minute Pascal wager.

The topic of secular dying has been on my mind for a while now. In the middle of 2016, I learned that an incurable cancer had taken lodging inside me. (Newfangled treatments that alter the immune system have stalled the cancer’s progress, at least for now, and given me more time than expected.) As I tried to sort things out, I thought of two scenes from the verge of secular death. One was fictional: Lord Marchmain, the bitter apostate from Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, made a sign of the cross as he received last rites, shortly before he died. The other scene came from a family memory. My younger brother Grant, an atheist through and through, was under hospice care with only another day or two to live. We gathered around him, keeping a fire going in the chilly living room, as he lay on the hospice bed. Strong opiates had done their work; we all assumed he would never regain consciousness. But when one of my sisters said something about “after he dies,” Grant suddenly burst out with his last words: “I don’t want to die!”

My challenge: find equanimity and some sense of cosmic resolution—which my brother apparently did not find—but without Lord Marchmain’s sacramental revival of faith. It’s not an easy thing to do. You might think that the warming support of family and friends would be a key to peace of mind, and anyone (secular or faithful) can find nourishment there. But here’s the problem: the more you focus on the people you love, the more unhappy you feel about leaving them for good.

As fate had it, when I received my diagnosis, I was writing an essay about “psychedelic last rites.” I was comparing the Catholic sacrament of extreme unction with a secular counterpart that deployed psychiatrists and psychedelic drugs instead of priests and oil. Scientists in the 1960s had experimented with LSD as therapy for terminal cancer patients who suffered from depression. The clinical trials showed promising results. But LSD was soon overwhelmed by bad publicity and regulatory opprobrium, and these experiments ceased. Recently, a few new psychedelic trials have begun, this time mainly with psilocybin. Again, results look quite promising.

I didn’t feel much of a need to participate in such a trial. I had studied the reports of both the early and the recent experiments, and I had my own psychedelic memories to draw on. My trips had happened long ago, in college, but the memories remained vivid. Facing death, I sought peace of mind by reviving my psychedelic insights and comparing them with what the clinical subjects reported about their therapy.

Let me admit, first of all, that I did not find comfort in the way that many have after their psychedelic doses. Both in early and recent trials, dying psychonauts marveled at the dissolution of the ego: conventional self and identity lost all meaning with the revelation of a seamless cosmic unity. Not for a moment would I doubt the validity and influence of such visions of transcendence. But they don’t work for me. There’s just too much I value that depends on the familiar old me (as delivered by the default mode network in my brain). Or, to put it another way: “I don’t want to dissolve my ego!”

So what else might serve? My secular self took comfort from two other residual effects of psychedelic experience. One came from a memory of a college acid trip. I realize that psychedelic profundities never translate very well onto the page, and I promise to deliver this one in as few words as possible. As I sat in a Santa Cruz meadow, it suddenly occurred to me that life and death are not opposites, or even two different things at all. “Lifedeath” is what we have.

The second comfort came more from a general psychedelic impression, rather than any one specific moment. Altered by these drugs, the mind discovers a transfigured natural world. Nature seems fresh, Edenic, infinitely interesting. This sort of inspiration helps to explain the effectiveness of LSD, even in microdoses, as treatment for depression. Do we really need God or the supernatural, given such a splendid natural world?

My recollection of psychedelic Eden has led me to appreciate the Enlightenment philosopher Spinoza as a kind of spiritual mentor. Spinoza has always been hard to label: Deist? Pantheist? Atheist? Referring to the uncaused cause at the foundation of the universe, he wrote, “Deus sive Natura”: God, or Nature. Take your pick. At least as I interpret this ambiguity, you can retain a sense of God (and all that implies), if it helps you—but you don’t need to. This world is enough.

I don’t want to leave the impression that my do-it-yourself psychedelic therapy has simply trumped uneasiness about death. It’s a new challenge every day, and I’m still working on some things, especially my perception of time. But for now, anyway, I don’t find myself as anxious as my brother was, or tempted to replace secular with sacramental dying.

Featured Image Credit: Big bubble, London by Berit. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The art of secular dying appeared first on OUPblog.

May 1, 2018

Professionalizing leadership – training

Barbara Kellerman looks at three crucial areas of learning leadership: leadership education; leadership training; and leadership development. In this second post, she discusses the importance of leadership training and how it should be approached and improved.

Leadership is taught as casually and carelessly as ubiquitously. With few exceptions, the leadership industry sends the mistaken, misguided, and misleading message that leadership can be learned quickly and easily in, say, a course or a workshop; in a year or even a term; in an executive program or a couple of coaching sessions. A far cry from professions such as medicine and law – and even from vocations such as hair dressing and truck driving, all of which presume first, a careful course of study and second, credentialing before permission to practice.

No such luck with leadership. Leadership, we seem to believe, can be learned on the fly or on the job. To wit the incumbent American president, who was elected to the nation’s highest office with zero political experience and zero policy expertise. It’s not acceptable for a plumber to be so woefully undereducated, so untrained, so completely undeveloped. Which raises this question: What if leadership were conceived a profession instead of an occupation? What then would leadership learning look like?

In my first post, I discussed what a good leadership education could consist of. I suggested that all leadership learners should be introduced to great ideas about power, authority, and influence, especially those in the great leadership literature. (Think Machiavelli and Marx, Freud and Friedan.) I further proposed that all leadership learners should be informed about the most important, relevant social science research. (Think Weber and Hollander, Milgram and Janis.) Finally, I recommended learning about leadership through art – such as music and film, painting and poetry. (Think Shakespeare and Scorsese, Beethoven and Dylan, Picasso and Basquiat.)

Let’s assume for the sake of this discussion that a good leadership education has been provided. What should come next? What constitutes good leadership training? Training in the world of work is presumed to provide the skills and behaviors necessary for good practice, for performing tasks typically associated with certain vocations or professions. Training is apprenticing that – ideally –weds experience to education. So, for example, after medical students have learned the fundamentals of the human body in a first-year course on anatomy, they go on, in their second year of medical school, to learn proper practice through clinical experience.

What constitutes good leadership training? Leadership training falls into three categories.

Leadership training falls into three categories. The first is skill development. Students of leadership are taught certain skills presumed to be particularly pertinent to the effective exercise of leadership. They include: communicating and collaborating; decision making and negotiating; persuading and influencing; organizing and strategizing. Because learning to lead is assumed a process that can be short and sweet, these skill development experiences are generally brief – at most a single semester. More typically they are embedded in executive programs, which are shorter in duration, many lasting no more than a week or even a weekend.

The second category of leadership training is experience, experience that can be and, some would argue, almost always should be, on the job. Jay Conger and Beth Benjamin describe this as “action learning,” a process by which leaders and managers learn from their own superiors and subordinates, and their own peers, in their own workplaces. In addition to external work, “experience” can reference internal work, such as developing self-awareness and undertaking self-analysis, alone and in groups. Reflections, self-reflections, such as these are now entrenched in many if not most leadership learning curricula, for instance at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business. A staple of its curriculum is LEAD, or Leadership Effectiveness and Development. The intention of the course is to “enhance self-awareness and to teach students how to learn the ‘right’ lessons from experience.”

Finally, leadership training includes what might more properly, or at least more precisely, be called management training. These consist of bread and butter instructions on how to run an organization or institution, no matter its type or task; small or large; public, private, or nonprofit. Such instructions might be on managing finances; managing technologies; managing marketing; managing people; and managing strategies, which is to say, implementing intentions deemed central or even critical.

During the last forty years the leadership industry has grown from incipient to a big, burgeoning, money-making machine. For various reasons – not the least of which is money – individuals and institutions that teach how to lead have come during this period to focus primarily or even exclusively on leadership training. Unlike professional schools, and for that matter vocational schools, they tend to neglect largely or even ignore entirely leadership education. This means that most leadership learners are being told to go to step two without even being informed about what I deem the critical importance of step one. This is not, then, to denigrate or diminish the importance of leadership training. Rather it is to argue that leadership teaching that is serious should be somewhat professional rather than simply occupational. First let’s provide leadership learners with a good education. Then we can, and should, proceed to provide them with good training.

Featured image credit: People Girls Women Students Friends by StockSnap. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post Professionalizing leadership – training appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers