Oxford University Press's Blog, page 255

May 14, 2018

What does it take to be a non-state armed group?

Armed groups are involved in the vast majority of today’s armed conflicts and crisis situations, and this trend is likely to continue. It is suggested that over recent years the number of groups involved in armed conflicts has quadrupled. For instance, studies have found that at some point, hundreds or even thousands of different armed groups operated in Syria. While in the late 20th century armed groups were normally clearly defined entities with distinct political and security agendas, today’s armed groups are often fractured, less structured, or operating in loose coalitions and with diverse agendas. Persons affected by their conduct may ask: are there any international rules regulating these groups? States fighting an armed group have to ask themselves: what group we are facing, and what level of violence are we permitted to apply in fighting them? Likewise, States considering whether to support an armed group have to carefully examine the group’s behaviour under international law. And in light of the seemingly unstoppable violence of some of these groups, at least some parts of the international community call for justice and for holding rebels to account for their crimes.

When examining possible international legal obligations of rebels, insurgents, terrorists, freedom fighters, or whatever other label one may give to non-state armed groups, the first and most elementary question is: is this group relevant under international law? In situations of conflict and violence, four elements can help us to respond.

1. It depends on the field of international law we are looking at

International law does not provide one single definition for non-state armed groups to be an “international legal person” vested with a fixed set of international rights and obligations. If we want to know whether a certain group is party to an armed conflict governed by international humanitarian law (IHL), bears human rights obligations, or if its members can be criminally responsible for certain acts, we have to examine the group in light of the body of law we are looking at. Having obligations under one field of law, or being able to commit one sort of international crime, does not necessarily mean that a group will also bear obligations in another field of law. Concretely, while an armed group may become party to an armed conflict, bound by IHL, and therefore among other things obliged not to torture prisoners, it is a completely different question of whether the same group is also obliged to fulfill the progressive realization of certain human rights in territory under its control (if we agree that armed groups have human rights obliagtions at all).

While in the late 20th century armed groups were normally clearly defined entities with distinct political and security agendas, today’s armed groups are often fractured, less structured, or operating in loose coalitions and with diverse agendas.

2. Not all “rebels” are automatically parties to armed conflicts

Armed groups emerge in different ways. Broadly speaking, while some consist primarily of defecting armed forces, as Mao Tse Tung remarked, others “spring from the masses of the people [and] suffer from lack of organization at the time of their formation.” Legally speaking, not all groups can be parties to an armed conflict. Looking only at the characteristics that a party to an armed conflict must have (and not at the other recognized criterion for the classification of non-international armed conflicts, namely the level of violence), three elements are key. First, an armed group must be a collective entity, meaning that it has a certain command structure that distinguishes the group from its individual members. Second, the group must have sufficient manpower, logistics (including weapons), and coordination to engage in intense and sustained violence. And third, the group needs to have a minimum level of discipline and the ability to implement basic rules. If that was not the case, imposing any rules on them would fail from the outset.

3. If members of such groups are able to commit an international crime, they are accountable

Once an armed group is party to an armed conflict, its members are liable for war crimes. However, it has been debated whether the commission of a “crime against humanity” or “genocide” requires State involvement. Under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, a crime against humanity requires a “State or organizational policy” behind the crimes (article 7(2)(a)). International courts have been clear that the required “organizational policy” can be that of an armed group. Indeed, if an armed group has the capacity to develop a criminal policy and to commit an attack against a civilian population in accordance with that policy, these acts may amount to crimes against humanity. If “unimaginable atrocities” (preamble of the Rome Statute) are committed, it should not matter whether the group behind these crimes is “State-like” or not—perpetrators should be accountable.

4. Armed groups differ widely—and the law needs to take this into account

The nature, organizational structure, and capacities of armed groups vary significantly. While some groups hide in the bushes and commit occasional hit-and-run attacks, others control territory in a State-like manner. In particular when considering whether armed groups should—or do—have human rights obligations, these differences need to be taken into account. When analysing the need of possible human rights obligations for armed groups, the first question should be whether, and to what extent, the State in whose territory the group operates is able to ensure respect for human rights by the group. If the State is unable to do so—either because it lost control over parts of its territory or is otherwise failing—there are strong reasons to demand armed groups to respect human rights. However, in practice and as a matter of policy, the question arises of whether it is at all feasible, or desirable, to require the group to also protect or fulfill the human rights in question? The response differs from case to case.

Featured image credit: Ongoing armed conflicts 2018 by Maresgoez. CC BY-SA 4.0, from Wikimedia Commons.

The post What does it take to be a non-state armed group? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 13, 2018

Considering the future of US-China diplomacy [excerpt]

Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Sino-US relations have overcome an intense impasse, adopting a much more intricate relationship driven by interdependent economies constant competition.

The following excerpt from The Third Revolution, Elizabeth C. Economy of the Council on Foreign Relations identifies ways that the United States and China might improve their diplomatic relationship.

There are many examples of successful US diplomatic efforts with China that have yielded important benefits globally. With US leadership, the two countries found common ground in advancing global cooperation on climate change, arresting the spread of Ebola, and preventing the development of nuclear weapons in Iran. Such cooperation is inevitably hard won. However, Xi Jinping’s ambition for China to assume a position of leadership in a globalized world has the potential to provide the United States with greater leverage in encouraging China to do more on the global stage.

Two areas of pressing importance where both countries could exert significant leadership and bolster their bilateral relationship are the global refugee crisis and the North Korean nuclear threat. Although the United States itself is less a leader in responding to refugee crises than previously— now seeking to limit the number of refugees it accepts— it continues to provide significant financial support globally for refugee support and relocation. China, however, has remained largely silent as millions flee conflict in the Middle East. Even more inexplicably, it has only reluctantly stepped up to help address the refugee crisis in its own backyard: the more than 650,000 Rohingya fleeing violence in Myanmar and seeking refuge in Bangladesh. It has limited its support to an offer to facilitate a bilateral dialogue between Bangladesh and Myanmar and a cautionary statement that the crisis should not slow down progress on the Bangladesh- China- India- Myanmar economic corridor—part of Beijing’s BRI. The United States, which has pledged tens of millions of dollars in aid for the refugees, threatened sanctions, and called for an investigation into the atrocities, should call on China as a regional and global power to do more.

The two countries found common ground in advancing global cooperation on climate change, arresting the spread of Ebola, and preventing the development of nuclear weapons in Iran.

Much as it did in the case of the Ebola epidemic, the United States should quietly draw attention to Beijing’s limited response, press it to provide financial as well as other assistance, and encourage it to use its extensive economic leverage in Myanmar to help bring a halt to the violence. Moreover, a coordinated response by the United States and China to provide assistance for the Rohingya’s safe passage back to Myanmar, assurances of citizenship, or resettlement elsewhere would send an important signal to Myanmar to resolve the crisis. As transpired in the case of climate change, it could also mark a first step in a broader international effort to address the global refugee crisis.

Cooperation between the United States and China is also essential in meeting the challenge of North Korea’s ballistic missile and nuclear weapons program. Both countries have devoted significant attention to the issue and agree on the objective of denuclearization on the Korean Peninsula, but options are limited. The Trump administration has persuaded China to adopt increasingly tough trade and other sanctions on North Korea, but the sanctions have yet to bring North Korea to the negotiating table. A preemptive military strike on North Korea would engender retaliation and devastating human and economic losses in South Korea, along with the potential to draw both the United States and China into military conflict. Simply allowing North Korea to continue on its current path directly endangers the security of the United States. And China’s double freeze proposal— in which the United States and South Korea freeze their military exercises in exchange for North Korea freezing its development and testing program— failed to engage the relevant parties.

Nonetheless, a combination of diplomacy and sanctions led by the United States and China remains the most viable path forward. Full enforcement of current sanctions by China is a first and necessary step. For its part, the United States should commit in earnest to a variant of China’s “freeze for freeze” proposal, agreeing to some “modest adjustment to conventional military exercises” while the parameters and sequencing of a potential agreement are determined. The United States and China could also take a page from their own history of diplomatic opening and use sports or culture to open the door to North Korea. There is no clear path forward, but setting the stage for more formal negotiations would be a first step.

As China’s ambition and footprint expand, the need for technical cooperation will grow.

Most US‒China diplomatic engagement operates not at the level of grand bargains to address global challenges, but at the more mundane level of technical cooperation around the big issues of global governance. The United States and China cooperate on a wide range of issues, including drug trafficking, cybercrimes and the dark web, counter-terrorism, and clean energy, among others. While these cooperative efforts do not often make headlines, they begin to build an institutional infrastructure for cooperation. And as one US state department official mentioned to me, “when you take politics out of the equation, cooperation can be quite good.”

As China’s ambition and footprint expand, the need for technical cooperation will grow. Future areas could include developing rules for limiting space debris or marine pollution in the Arctic, both of which are building blocks in a much larger area of potential conflict in global governance between the United States and China. Another issue of particular importance is coordinating standards for development finance. Working with Chinese development banks to ensure Chinese companies adopt best practices in the environment, regarding labor, and in transparency as they advance the BRI is essential to preserving the competitiveness of American companies. The United States could further its economic interests in this regard by joining the AIIB.

While advancing US interests through diplomatic engagement with China represents the ideal in the Sino-American relationship, the often differing values, priorities, and policies of the two countries necessitates that the United States also maintains a range of alternatives in its toolbox. Partnering with allies and others in Asia, Europe, and elsewhere is an important element of US policy toward China. President Trump’s call for greater burden sharing does not need to be understood as a retreat by the United States from global leadership, but rather as an opportunity for other regional powers to assume a greater role in addressing shared challenges.

Featured image credit: President Trump’s Trip to Asia by The White House / Shealah Craighead. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Considering the future of US-China diplomacy [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

May 12, 2018

Preparing for disasters: a corporate catastrophe checklist

Facebook has been in the hot seat since it came to light that personal data on as many 87 million users, mostly in the US, had been improperly acquired by Cambridge Analytica for use in the presidential campaign of Donald J. Trump. CEO Mark Zuckerberg acknowledged as well that “malicious” outsiders may have accessed profiles of most of his 2 billion users. In the wake of Facebook’s enormous cyber-lapse, Congress investigated, users fled, and its stock plummeted—the makings of a genuine company disaster.

But cybersecurity—or the lack thereof—is just the latest source of catastrophic risk, with a flurry of data breaches in recent months exposing consumer records across a wide swath of business firms, non-profit organizations, and government agencies. Cyber risk joins terrorism, financial crises, and natural disasters in disrupting the operations of many.

Some disruptions are global. The subprime mortgage meltdown in 2008 in the US became toxic for financial institutions everywhere. The Fukushima reactor meltdown in Japan in 2011 shut auto suppliers that in turn closed car assembly around the world.

“Whatever the disasters’ causes, firms can and should ready themselves to avert them and to rebound if they do strike.”

Occasionally, disasters are self-inflicted, as was evident when engineers at Volkswagen installed deceptive emissions equipment in more than 11 million vehicles from 2009 to 2015. And bankers at Wells Fargo created millions of unauthorized bank and credit card accounts without their customers’ knowledge in the mid-2010s. Both firms ousted executives, forfeited earnings, and suffered plummeting share prices.

Whatever the disasters’ causes, firms can and should ready themselves to avert them and to rebound if they do strike. Some have been preemptively doing just that, learning from the experience of others. But they have had to overcome a host of impediments that thwarts risk readiness at many companies.

At the top of the list is myopia. Some organizations, for instance, perceive the likelihood of a disastrous event next year to be so low that it drops below their threshold of concern. The “not-invented-here” syndrome, a well-known barrier to product innovation, has led others to simply ignore what leading firms have already put in place.

Facebook executives might have wisely investigated the massive breaches of company firewalls that had recently compromised vast amounts of confidential customer records at other firms, including Target (40 million records), Anthem (80 million records), Equifax (143 million customers), eBay (145 million records), and Yahoo (3 billion). Facebook could also have usefully studied what those companies have done to prevent future attacks.

Firms can learn much from others’ experience, and to that end, we have looked at risk management measures among 100-plus large companies in the US and abroad. From that, we have built an eight-point checklist for mastering catastrophes at any enterprise:

Catastrophes are on the rise, and your firm may be next in line. Don’t pretend it cannot happen to you, and instead imagine five potential disruptions including a worst-case scenario that could threaten the entire enterprise.

Recognize behavioral biases that misdirect company decisions. Intuitive thinking can lead you to underestimate low-probability risks and mismanage recovery efforts.

Reframe the risks so that managers pay attention to them. Stretch the time frame for judging disasters so that a 1-in-100 likelihood of an event next year is viewed instead as a 1-in-5 chance of occurring over the next 25 years.

Define your firm’s risk appetite and risk tolerance. Identify and balance risk appetite and risk tolerance in mapping your company’s overall strategy, and prioritize the enterprise risks that demand attention now.

Take steps now to invest in protective measures. Design multi-year budgets that spread out the high upfront costs of risk-mitigation measures so the expected long-term benefits of those investments can be justified now.

Learn from your own adverse events and near misses as well as those of others. Take advantage of a calamity or close call to redesign your enterprise for preparedness and resilience.

Protect against extreme losses by transferring some of the risk. Use insurance and other risk transfers to buffer against events that can gravely threaten the firm.

Attract and prepare the next generation of risk leaders. Prepare future managers to avoid behavioral biases and engage them in deliberative thinking for building risk-management capabilities throughout the firm.

Watch now, as Facebook and its leaders work to extricate themselves from the worst crisis the firm has ever experienced. And as we learn from it and the experiences of others, all of us will be in a better position to face worst-case scenarios and plan for resilient responses, whether a major flood, technological blow-up, or cyber-attack. In doing so, we can make the mastery of catastrophic risk a source of sustainable advantage, rooted in the well-known mantra, expect the unexpected.

Featured image credit: “Facebook-76536 640” by Simon Steinberger. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Preparing for disasters: a corporate catastrophe checklist appeared first on OUPblog.

May 11, 2018

Mexican Women’s Self-Expression through Dress – Episode 43 – The Oxford Comment

Our host for this episode is William Beezley, Professor of History at the University of Arizona and Editor in Chief of the . He moderates a roundtable discussion with historians Stephanie Wood and Susie Porter about Mexican women’s self-expression through textiles and dress throughout history to the present day.

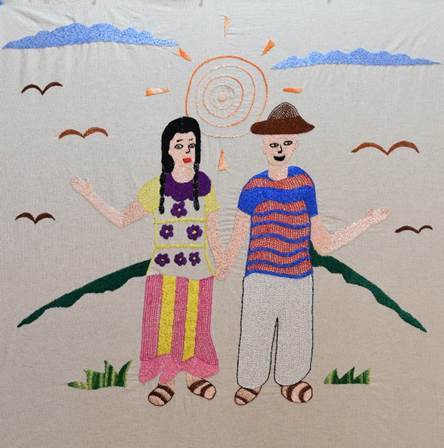

Societal changes in post-revolutionary Mexico of the 1920s produced shifts in urban women’s activity and mobility that were reflected in their dress and appropriation of indigenous stylistic and symbolic traditions. Women today continue to use traditional forms, such as embroidered huipiles, as a means of expressing their identities and rights through fabric.

Painting of a woman at a back-strap loom, from a copy of the Mapa de Cuauhtlantzinco, San Juan Cuautlancingo, Puebla. Courtesy The Museum of Natural and Cultural History, University of Oregon. Photograph: Jack Liu.

Butterfly huipil. San Andrés Chicahuaxtla, Oaxaca. Photograph: Stephanie Wood.

Sueños de migrantes wall hanging. San Francisco Tanivet, Oaxaca. Photograph: Robert Haskett.

Wall hanging depicting a woman calling her son, who is working as a chef in the United States. San Francisco Tanivet, Oaxaca. Photograph: Stephanie Wood.

Rufina Montaño Bocardo, Derecho a una vida libre de violencia. Tapestry hand-embroidered with silk thread. Coyomeapan, Puebla.

Crispina Osio Saldaña, Derecho a la igualdad. Tapestry hand-embroidered with silk thread. Coyomeapan, Puebla.

Susana Abrego Pacheco, Derecho al voto. Tapestry hand-embroidered with silk thread. Coyomeapan, Puebla.

Minerva Lozano Gil, Derecho a la justicia. Tapestry hand-embroidered with silk thread. Coyomeapan, Puebla.

Featured image credit: Photo courtesy of Stephanie Wood.

The post Mexican Women’s Self-Expression through Dress – Episode 43 – The Oxford Comment appeared first on OUPblog.

The evolution of pain medicine adherence [extract]

Pain medicine adherence, the extent to which patients follow a treatment plan for managing pain, has remained a challenge to doctors and patients alike for millennia. Risks abound, from not taking enough medication, to taking too much and/or becoming dependent on it, with the current opioid epidemic in the United States providing a clear example of the latter in action. The following edited extract, from Facilitating Treatment Adherence in Pain Medicine examines the history of pain medicine adherence, from ancient Greece to the present day.

In 2003, the World Health Organization published the document Adherence to Long-term Therapies: Evidence for Action. The issue of adherence was addressed in a number of disease-specific reviews, including, asthma, cancer, depression, palliative care, diabetes, epilepsy, HIV/AIDS, hypertension, tobacco smoking cessation, and tuberculosis. Missing was the area of chronic non-cancer pain, which affects approximately 30% of the American population and costs $560 billon to $600 billion per year in the United States. This impressive volume of work by leaders in their various areas of expertise generated a number of “take-home” messages that are particularly salient to the discussion of adherence with regard to pain-related healthcare outcomes:

• “Poor adherence to treatment of chronic disease is a worldwide problem of striking magnitude.”

• “The impact of poor adherence grows as the burden of chronic disease grows worldwide.”

• “The consequences of poor adherence to long-term therapies are poor health outcomes and increased healthcare costs.”

• “Improving adherence also enhances patient safety.”

• “Increasing the effectiveness of adherence interventions may have a far greater impact on the health of the population than any improvement in specific medical treatments.”

• “Patients need to be supported, not blamed.”

• “Health professionals need to be trained in adherence.

Dating back to the earliest Western writings about patient behaviour, the willingness or ability of patients to follow a recommended treatment plan has been recognized as an important issue—and one that in contemporary times is a major determinant of health-related outcomes. Hippocrates cautioned his contemporaries to “Keep a watch also on the faults of the patients, which often make them lie about the taking of things prescribed. For through not taking disagreeable drinks, purgative or other, they sometimes die.” In modern times, healthcare providers continue to be concerned with issues of patient compliance and nonadherence to treatment regimens but often feel ill equipped to influence it. In undergraduate and postgraduate medical education, little is taught about this critical issue.

‘Adherence depends on a strong clinician–patient therapeutic alliance and developing a trusting relationship that is based on collaboration’

Surveys of healthcare providers indicate that one of the most distressing features of clinical practices is that of patient nonadherence. Oftentimes the words compliance and adherence are used interchangeably, but they really do denote very different levels of intent. Compliance refers to the extent that patients are obedient to prescriptive instructions of healthcare providers, thus suggesting that noncompliance is a volitional act of disobeying salutary recommendations. Adherence implies a more active, voluntary, and collaborative involvement of the patient in a mutually acceptable course of behaviour to produce a desired preventative or therapeutic result.

The World Health Organization defines adherence as “The extent to which a person’s behaviour taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider.” It was R. B. Haynes who succinctly brought into clear focus the relevance of this clinical construct, stating that “Increasing the effectiveness of adherence interventions may have a far greater impact on the health of the population than any improvement in specific medical treatments.”

But through the lens of history and patients’ perspectives, there may be unwitting survival benefits of nonadherence. A century ago Chapin (Charles V.) commented on the state of medical care at the time, averring, “We might not be surprised that people do not believe all we say, and often fail to take us seriously. If their memories were better they would trust us even less.” Iatrogenic complications of treatment and frequency of adverse drug effects continue to be commonplace. And with the advent of the Internet and direct-to-consumer advertising, patients are receiving a barrage of information regarding medical care that can cause scepticism, erode the patient–physician relationship, and increase the rate of nonadherence.

Notwithstanding—but clearly recognizing—these very real concerns, and within the personalised context of each patient’s individual circumstances, considerations of adherence must be aligned with and tied to the patient’s treatment goals and objectives, self-view and perceptions of quality of life, adjustment to an acute or chronic condition, ability to cope with illness over time, social support systems, and ability to make autonomous decisions. Adherence depends on a strong clinician–patient therapeutic alliance and developing a trusting relationship that is based on collaboration. It is also becoming clear that this necessary therapeutic alliance is far from sufficient to guarantee adherence. Many other factors are determinative, and perhaps predictive, of adherence. But oftentimes, nonadherence can be attributed to a breakdown of the therapeutic relationship, a misunderstanding of instructions from the healthcare provider, or barriers within the healthcare system itself.

Featured image credit: ‘Glass bottles with labels’ by Daria Nepriakhina. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post The evolution of pain medicine adherence [extract] appeared first on OUPblog.

May 10, 2018

How the intention to share photos can undermine enjoyment

Though people both take and share more photos than ever before, we know very little about how different reasons for taking photos impact people’s actual experiences. For instance, when touring a city, some people take photos to share with others (e.g., to post on Facebook), while others take photos for themselves (e.g., to remember an experience later on). Will those who take photos to share enjoy the experience more or less than those who take photos for themselves? How do people’s goals for taking photos impact their enjoyment of photographed experiences?

In 12 studies with over 2,800 participants, results show that in fact those who take photos to share with others, compared to those who take photos for themselves, enjoy the photographed experiences less.

In one study, tourists lined up to take a photo at the famous Rocky statue in Philadelphia were asked whether these photos were intended for themselves or to share. Then, after they took the photo, they were asked how much they enjoyed the experience. Based on their answers in conjunction with other studies it was found that those who take photos to share enjoy the experience less, and are less likely to recommend the experience to a friend, compared to those who take photos for themselves.

Similar effects were found when people were asked to take photos during their Christmas celebrations. Participants were tasked to take photos on 25 December for a photo album that was either just for themselves or to share on social media platforms, such as Facebook. Interestingly, the albums created for sharing differed from those created for personal usage. Albums created for sharing featured more photos where people were posed (as opposed to candid) and where people were smiling, suggesting that they wanted to present a positive impression to the viewers of the album. In addition, with shared albums, people were more likely to include photos that included items typical of the holiday (e.g., Christmas trees, stockings, etc.), suggesting that they felt the need to provide details about the context for those who were not there. Further, those that were told to take photos to share enjoyed the photo-taking experience less than those who took photos for themselves.

Why would the reasons for taking photos affect one’s enjoyment of the experience?

But why is that the case? Why would the reasons for taking photos affect one’s enjoyment of the experience? Findings suggest that this occurs because taking photos to share increases photographers’ concerns about how others will judge their photos. This intent to share with others increases feelings of anxiety to present oneself in a positive light, which in turn reduces enjoyment during the experience. In addition, these negative feelings extend to people’s interest in participating in similar future experiences, such that taking photos to share actually decreases their desire to repeat that experience again.

This is even the case when the person taking the photo is not personally in the photo, such as when sharing a photo of a sunset or, in the previous study, a Christmas tree. Some people experienced these negative effects of intending to share worse than others. Those who are high in self-consciousness (those who are highly concerned how they appear to others and what others think about them) show stronger effects; that is, when they take photos to share, they enjoy experience less not just compared to taking photos for themselves but also compared to those who do not worry so much about what others think of them.

Does it matter who sees the photos? It was investigated whether the audience with whom one shares matters. We reasoned that intending to share one’s photos with a broad group of acquaintances (e.g., all friends on Facebook) would reduce enjoyment, but taking photos to share only with close friends or for one’s own personal album would make the experience itself significantly more enjoyable. Indeed, that was the case, participants taking photos to share with people they did not know very well and who do not them well, led to feelings of anxiety and also reduced how engaged they felt in the experience. They worried about what others thought and hence were less present in their own experience, causing them to enjoy the experience less.

Moreover, our work also identifies a potential misstep among businesses — encouraging consumers to take photos to share during experiences may be counterproductive. For instance, many restaurants and hotels incorporate hashtags throughout their experiences to encourage consumers to take photos for sharing on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter. Such salient reminders might have unintended costs if they reduce the enjoyment people feel during the experience itself, with potentially harmful effects on remembered enjoyment. Moreover, these negative effects on consumers’ experiences may reduce their propensity to repeat experiences or recommend them to others.

Our experiences are vital to our well-being, and understanding what affects our enjoyment of experiences is important both to people seeking happiness and to companies creating and marketing such experiences. Experiences are also widely shared with others, not only through written and verbal communication, but increasingly through photos. More and more, photos are taken as experience unfold, and hundreds of millions of these photos are shared every day through social media and other channels. While consumers may enjoy sharing these photos later on, and find value in receiving “likes” and “comments” when they do, they may want to consider how taking photos to share can undermine their own enjoyment during the actual experience itself.

Image credit: “Leaf” by Maria Shanina. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post How the intention to share photos can undermine enjoyment appeared first on OUPblog.

Animal of the Month: 11 facts about koalas

Koalas: the adorable fluffy mascots of Australia who seem to cuddle everything in sight. It’s no wonder that tourists flock to visit them, photograph them, and feed them the leaves of their all-time favourite food, eucalyptus. Apart from their tree-hugging habits and rigid diet though, how much do you actually know about them?

The koala is part of the marsupial family, which is around 80 million years old. Marsupials only comprise 7% of the world’s mammal population, and koalas themselves only have one species: Phascolarctos cinereus. This unique species has a number of exceptional characteristics, however, and what they lack in diversity they more than make up for in bellows, sleeping patterns, and chlamydia. Learn about these koala characteristics, plus many more, with our 11 facts that you may not have known about koalas.

1. Etymology: Part 1

The word koala comes from a mispronunciation of the Eora word gula, of uncertain meaning. Koala is one of several aboriginal words to have been adopted into modern English, alongside words like budgerigar, wombat, and boomerang.

2. Etymology: Part 2

Another note on etymology – despite the word often appearing alongside koala, they are not in fact related to bears in any way. They were given the name ‘koala bear’ by European settlers due to their slight resemblance to bears in Europe.

3. Koalas and settlers

European settlers in Australia prized koalas’ thick grey coats, and killed millions of them in order to ship their pelts back to Europe. They were nearly driven to extinction in the early 20th century as a result, but a mixture of public outcry and hunting bans in the 1940s saved them from disappearing for good.

4. Chlamydia

All koalas in northern Australia, and many koalas elsewhere in the country, are infected by what is known as the Koala Retrovirus, which likely causes immunosuppression. This leads to koalas being susceptible to secondary and often fatal pathologies such as Chlamydia infection or leukemias. Studies have indicated that it entered the koala population within the last two centuries.

Image credit: ‘Koala at Amity Point’ by S. Newrick. CC 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: ‘Koala at Amity Point’ by S. Newrick. CC 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.5. Eucalyptus

Koalas love eucalyptus, a genus of tree native to Australia, and they spend most of their lives in these trees. There are over 600 species of eucalyptus, and their leaves are extremely fibrous – so much so that they are inedible to most herbivores. They are also low in essential nutrients, including nitrogen and phosphorus; and contain high concentrations of indigestible structural materials such as cellulose and lignin. Last but not least, they are laced with poisonous phenolics and terpenes (essential oils). Koalas are adapted to cope with all of these factors, however, with specially adapted teeth for grinding down the leaves, elongated caeca to allow for microbial fermentation, and sleeping patterns which involve them snoozing for up to 20 hours a day!

6. Paws

Koalas have large paws and strong razor-sharp claws, which they use to help heave themselves up smooth-barked eucalyptus trees. They also have two opposable digits on their forepaws which allow them to grip onto small branches and climb into outer canopies.

7. Bellowing

Male koalas fill the forests with their curious mating bellows during the early months of the koala breeding season. These bellows are made possible due to an extra set of vocal chords possessed by male koalas in their pharynx. They are made to both attract mates and to warn off potential mating rivals, and scientists have found that koalas tend to bellow less in certain weather conditions.

8. Pouches

Koalas are marsupials, an order comprised of 250 animals that are distinctive due to their reproductive methods. Unlike most other mammals, marsupial embryos undergo very little placental development, and are born very early in their development. The young are then transferred to a pouch, where they suckle milk and complete the rest of their development. In the case of koalas, the babies are born weighing approximately 0.5g, and climb unaided into their mothers’ pouches. The name marsupial is derived from the name of these pouches, marsupium, which comes from the Greek marsupion, ‘pouch’.

9. Habitats

Koalas can usually be found where eucalyptus are found, meaning that despite often being viewed as fragile and vulnerable, they are hardy little guys that can withstand many different types of habitat. These include wet montane forests in the south, vine thickets in the tropical north, and woodlands in the semiarid west of their range. Their territory covers several hundred thousands of square kilometers, across eastern Australia from the edge of the Atherton Tablelands in North Queensland to Cape Otway at the southernmost tip of Victoria.

10. Population

It is suggested that the total koala population is between 40,000 and 1 million animals. Whilst historically koalas are rare on the mainland, overpopulation is a big issue on offshore islands in the south. Over 10,000 koalas from these islands have been relocated to the mainland in the last 75 years. However, the problem of overpopulation seems to have simply been transferred to these mainland locations, meaning that other options are having to be discussed. Culling koalas is a vastly unpopular option, so researchers are currently considering introducing birth control as an alternative.

11. Climate change

Despite the fact that their populations are thriving in certain parts of Australia, koalas are, like many other animals, suffering significantly as a result of climate change. Koalas release certain hormones when they are stressed, which usually help to regulate almost all of their biological processes, and undue changes to the usual flow of these hormones can have a huge impact on their general health, fitness, and survival. Studies have found high levels of these hormones in koalas at the arid edges of their range, suggesting that koalas may be struggling to cope at the periphery of their ranges, and this may be exacerbated by variations in dietary composition with ongoing climate change.

Featured image credit: “Koala Bears Tree Sitting Perched Portrait Grey” by skeeze. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Animal of the Month: 11 facts about koalas appeared first on OUPblog.

Secret history: uncovering stories that never officially happened

Spy fiction has been a popular genre for over 100 years. Tales of Bond and Bourne continue to fascinate audiences worldwide. Sometimes, however, the realities of the shadowy world of espionage can be just as engrossing.

There is just one problem: finding out what actually happened.

This is especially the case when writing about deniable interference in the affairs of others: intelligence officers know it as “covert action.” Covert action involves using spies to influence events in other countries. Highly controversial, it is perhaps the most sensitive—and secretive—of all government activity.

Many countries engage in covert action. Most recently, Russia stands accused, among other things, of interfering in the 2016 US presidential election. Meanwhile, the US has a long track record of using the CIA to overthrow governments abroad. Israel has a reputation for particularly robust covert action against Arab states and terrorists alike.

The United Kingdom is not immune. It has used covert action for hundreds of years—since before the United Kingdom even existed. Queen Elizabeth I used “covert meanes” against King Philip of Spain in the Low Countries by secretly providing funds for rebel fighters. The reign of her namesake, Queen Elizabeth II, witnessed a dizzying array of secret schemes to promote British interests as London’s international power waned.

There are numerous ways to write secret history—and challenge government secrecy. Most importantly, more exists in the archives than people realise.

These included plans to overthrow the Albanian government and undermine Soviet rule throughout Eastern Europe. The Foreign Office cynically hoped to provoke repression for use in Western propaganda. In the Middle East, Brits helped overthrow the Iranian government, planned to kidnap a Saudi Sheikh, colluded with allies to overthrow the Syrian regime (twice), and waged sabotage operations against Yemen. Even the Queen herself once suggested quietly slipping something into the coffee of a Middle Eastern leader.

A lot of this was achieved using a top-secret MI6 fund, about which even the prime minister did not know.

In the declining empire, psychological warfare teams plotted to spread fake epidemics so as to flush rebels out of forests. In Latin America, the Foreign Office turned to psychics to locate a kidnapped diplomat. Closer to home, the most senior levels of government supported risky undercover hit squads in Northern Ireland.

They had few scruples about lying to the United Nations and Parliament.

This is secret history. MI6 files remain classified and many of these operations are still not officially acknowledged many decades later. This poses a serious—if enticing—challenge to historians wanting a fuller picture of how the UK waged Cold War and managed the end of empire.

There are numerous ways to write secret history—and challenge government secrecy. Most importantly, more exists in the archives than people realise. Of course, there is no neat “covert action” file series, but fragments dispersed amongst thousands of pages provide tantalising details. They often exist in what we might call parallel files. For example, MI6 budgets are classified but there might well be some hints in seemingly mundane Treasury files. Stumbling upon a diamond amidst pages of dust is a real thrill. An ageing historian suppressing the urge to dance a jig in the archives is not an uncommon sight.

The wonderful National Archives, however, are no history supermarket. Writing secret history requires an expedition to as many repositories as possible—a great archival road trip. These include reading private papers held in universities up and down the country. One historian found British assassination plots against Syrian officials buried in a politician’s private papers that had been accidentally declassified in Cambridge. The Queen’s coffee remark, mentioned above, sat quietly for decades in a diplomat’s unpublished diary in Birmingham.

This archival trail extends across North America. From the glamour of presidential libraries in Los Angeles—where, alongside tourists taking photographs of Reagan’s Air Force One, details of British involvement in the Iran-Contra scandal lie dormant—to the small-town romance of libraries in the mid-West. Fleeing hurricanes in the Kansas countryside may be a very real danger, but the rewards—such as uncovering Anglo-American collusion to overthrow governments—can be great.

Skeletal documents can only take the historian so far. Interviews are vital. People who have “been there and done that” help put archival fragments in the right order. One of the great pleasures of writing secret history is meeting interesting characters in interesting locations, from sprawling Scottish estates to London’s clubland. Stories told over a brandy or two—many of which cannot be published—are a privilege to hear. Retired officials are often surprised about how much historians have uncovered, and struggle to hide their expression upon seeing a document in which he or she signed off a covert operation decades ago.

Secret history can—and needs to—be uncovered. It is more than spy stories. We cannot fully understand state interaction without including the darker arts of international relations.

Featured image credit: Shredder_mechanically_device by Stux. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post Secret history: uncovering stories that never officially happened appeared first on OUPblog.

May 9, 2018

In the cattle world Part 2: Mostly bucks and bulls

The buck stops nowhere: it has conquered nearly all of Eurasia. The Modern English word refers to the stag. At one time, it was a synonym of he-goat, or Billy goat. But Old Engl. buc “stag” seems to have coexisted with bucca “Billy goat.” Perhaps later they merged. German Bock is a rather general designation of “male animal,” such as “ram” (or “wether”; wether is a nearly forgotten word, though still recognizable in bellwether), “stag,” and others; it is a common second element of compounds like Schafbock (Schaf “sheep”). Old Icelandic bukkr ~ bokkr also meant “ram.” Those who have read last week’s post on cow (Part 1 of the series) will immediately draw two conclusions. First: the word probably had a generic meaning, a male horned animal, with the specialized sense being the result of the more or less unpredictable narrowing of meaning. Second: bukkr ~ bokkr has a long consonant (a geminate), discussed a week ago in connection with Latin vacca “cow” (and in general, bokk– and vacc– sound rather similar) and may be an expressive word.

A stag party. So far, no horns. Image credit: Bachelor Party by Partybus Buenos Alres. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

A stag party. So far, no horns. Image credit: Bachelor Party by Partybus Buenos Alres. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Also, last time a possible onomatopoeic origin of the Indo-European word for “cow” was discussed, and I wrote that, although moo– is what most people hear the cow “say,” other variants have often been recorded. One of such variants begins with b-. The bull’s warlike roar is different from the cow’s lugubrious mooing. In any case, the Lithuanian verb is būkti “to moo” (Latvian bucêt means “to sound; roar”), and Czech has býkati ~ búkati “to moo”; all of them begin with b-. When it comes to the animal name, in Slavic we find byk (and similar forms); in the Turkish languages, buka and buga; in Middle Irish bocc; in Avestan (an old Iranian language) būza; in Armenian, bowk ~ buc “lamb.” The Celtic form boukkô– means “cow,” for instance, Old Irish boc ~ bocc and Welsh bwyc ~ bwych. Vowels vary slightly, as often happens in sound-imitative words. If we are indeed dealing with a sound-imitative formation, then bock and its linguistic relatives need not be migratory words (a category, also mentioned last week); they are rather products of spontaneous word creation, as the distinguished Swiss linguist Wilhelm Oehl called such a process.

Incidentally, buck may go back to the Indo-European past, even if it was not sound-imitative. We should only remember that the oldest Indo-European words hardly ever began with a b, though in expressive and onomatopoeic words b did occur. Only the sound, reconstructed as bh was common; allegedly, it became b in Germanic by the First Consonant Shift, celebrated a week ago and many times earlier. A bold hypothesis connects our noun with the participle of the verb represented in English by bow “to bend,” from Old Engl. būgan (compare German biegen; its past participle is gebogen). According to this hypothesis, buck emerged as the name of an animal with bent horns. Such an etymology presupposes that the verbs, cited above, are derived from the animal name. The Indo-European word could spread to Turkic, or in one language family this word might be onomatopoeic, while in another it might derive from a participle like Modern German gebogen (from bhugno-).

Zeus and Europe. Beware of amorous bulls (and swans). Rain can also be dangerous, and so can everything else. Image credit: The Abduction of Europa, 1716 by Jean François de Troy. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Zeus and Europe. Beware of amorous bulls (and swans). Rain can also be dangerous, and so can everything else. Image credit: The Abduction of Europa, 1716 by Jean François de Troy. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.To realize even more clearly how slippery our path is, we might look at Italian becco. There is becco “beak” and becco “Billy goat.” Engl. beak is of course a borrowing from Old French; all its Romance cognates derive from the Latin loanword beccus, which is of Celtic origin. Birds’ beaks can be bent, and we do find Old Irish bac “hook.” The Italian becco “Billy goat” is also in good company: compare French bouc (the same meaning), unless both are from Germanic; bique “Nanny goat,” and even biche “doe.” It is anybody’s guess whether becco1 and becco2 are related. All these words are of uncertain origin.

At one time, I discussed the etymology of Engl. bitch (11 May 2016) and mentioned in passing French biche “doe.” Etruscan, Caucasian, and Avestan sources have been offered for some of the above-mentioned words. Faced with this embarrassment of riches (embarras de richesses), one, naturally, begins to favor the onomatopoeic hypothesis or rely on a migratory word, though neither will explain all those animal names. Only one conclusion appears as certain: it is hard to be an etymological toreador.

An etymologist and his triumph. Image credit: Miura, Fundi, Sevilla Abril, 09 by Fiskeharrison. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

An etymologist and his triumph. Image credit: Miura, Fundi, Sevilla Abril, 09 by Fiskeharrison. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.In contrast to the multiple conjectures about buck, there used to be touching unanimity with regard to bull. In Old English, only the diminutive bulluc “bullock” (that is, “young bull”) has been recorded, with the suffix familiar from the modern word hillock and a few others, but in most cases, this suffix has merged with the root (as in mattock), and we can no longer isolate it. However, late Old English bula seems to have existed. And it was probably a native word, not a borrowing from Scandinavian. Even in Germanic, exact analogs of bull are few: Dutch bul and Old Icelandic bolli. Also, Lithuanian has bullus (native?). The animal’s name, our classic dictionaries suggest, has the same root as Engl. ball and Greek phallós “phallus.” Its meaning was reconstructed as “swollen.”

This etymology works very well for phallus; ball, as in football; and ball “testicle” (a round, “swollen” object). The bull was supposedly named for its function as a breeder, the bearer of its genital organ. But a word with such a solid Indo-European etymology could have been expected to turn up not only in Lithuanian and in part of Germanic (there is no German congener); it is a North Sea animal name. In any case, it would make more sense to interpret bull as a huge (“swollen”) animal rather than as a procreator. The editors of the OED online showed no enthusiasm for the traditional view. They didn’t even mention the phallus/ball etymology and preferred the sound imitative origin of bull. Unfortunately, the persuasive verbs that fit this agenda are few: only German dialectal bullen ~ büllen and possibly bellen “to bark.” The origin of very old animal names is usually beyond reconstruction, though the options are few.

Are we at the end of our journey? Oh, no, don’t forget steer and ox. Unlike the bull, those beasts are not potent, for both words most usually refer to castrated animals. A steer is typically a young ox. The family of both words is large. Dutch and German have stier ~ Stier, very probably related to Latin taurus and Classical Greek taurôs. We note that the last-named two words lack the initial consonant. Every now and then an enigmatic figure turns up in our stories. It is called movable s or s mobile. For the reasons that have never been discovered, words sometimes lose s at the beginning of the root. Here it is missing even in the Scandinavian cognate, for the Icelandic word is þjórr (þ = Engl. th, as in thigh). By the First Consonant Shift, Indo-European t became Germanic þ. This means that the protoform of þjórr did begin with t, as in taurus. (If someone has noticed that in steer and its likes, we have t, rather than þ, here is the answer: t was not shifted after s.)

All is fine, except that no one knows the etymology of steer. Even Gothic had this word (stiur “calf”), but, alas, so did Aramaic (tōr), Hebrew (šor), and Assyrian (šūru). Another migratory word? Perhaps. People drove their herds from one pasture to another, came into contact with their sometimes distant neighbors, and taught them the words they used. You remember what happened to Little Bo-Peep? We have a motley herd. Let us leave it alone for the time being and hope that the animals will come home and bring their tails and tales after. And ox? If I may, I will now imitate the great medieval German poet Gottfried, the author of Tristan, and finish my story so.—About ox I won’t tell you anything. –Oh, do tell us! –All right. Next time.

The buck stops here. Image credit: Harry Truman poses for a photograph at the recreation of the Truman Oval Office at the Truman Library in 1959 via the Truman Library. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The buck stops here. Image credit: Harry Truman poses for a photograph at the recreation of the Truman Oval Office at the Truman Library in 1959 via the Truman Library. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.TOWARD THE SPELLING CONGRESS, LONDON, MAY 30, 2018

Some of our readers may be interested in what will happen after the congress. The Spelling Society will work with Expert Commissioners, not necessarily academics (just a group of people well-versed in spelling issues). Several, perhaps numerous, alternative spelling schemes will be offered, and the Commissioners will choose a few that will look especially promising. Those schemes will be widely discussed and eventually form the backbone of the reform. Changing English spelling is a delicate matter, and even a modest first step in the desired direction will be a stupendous achievement.

Featured Image: Bovine creatures are supposed to have a corresponding expression when staring at a new gate. They stop there, as it were. Featured Image Credit: “Cows Animals Farm Grass Fence” by Free-Photos. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post In the cattle world Part 2: Mostly bucks and bulls appeared first on OUPblog.

Translanguaging and Code-Switching: what’s the difference?

One of the most frequently asked questions after a presentation on Translanguaging has been, what’s the difference between Code-Switching and Translanguaging? In fact, I have had members of the audience and students come up to me with transcripts of speech or writing that involve multiple named languages and ask: “Is this Code-Switching or Translanguaging?”

Code-Switching

Code-switching refers to the alternation between languages in a specific communicative episode, like a conversation or an email exchange or indeed signs like the ones above. The alternation usually occurs at specific points of the communicative episode and, as linguistics research demonstrates, is governed by grammatical, as well as interactional (conversational sequencing), rules. The starting point of any analysis of Code-Switching is usually the identification of the languages involved; it then proceeds with either a structural or a functional analysis in terms of the process of integrating different grammatical systems into one coherent unit and the non-linguistic purposes switching from one language to another at a particular point might serve.

The term Code-Switching has been in academic discourse for decades; it is well established as a linguistic concept and has been studied by many scholars from different perspectives. There are books, journal special issues, hundreds of articles, and international conferences, devoted to the study of Code-Switching, and some people feel particularly precious when another concept emerges, seemingly with a vengeance, to take over the discourse space. So the first thing I normally say to people is that Translanguaging is not intended to replace Code-Switching at all. They are two very different theoretical and analytical concepts, coming from very different origins.

Translanguaging

In contrast, is not an object or a thing-in-itself to identify and analyse; it is a process of meaning- and sense-making. The analytical focus is therefore on how the language user draws upon different linguistic, cognitive and semiotic resources to make meaning and make sense. The identities of individual languages in structural and/or socio-political terms only become relevant when the user deliberately manipulates them. Moreover, Translanguaging defines language as a multilingual, multimodal, and multisensory sense- and meaning-making resource. In doing so, it seeks to challenge boundaries: boundaries between named languages, boundaries between the so-called linguistic, paralinguistic and non-linguistic means of communication, and boundaries between language and other human cognitive capacities. Language in its conventional sense of speech and writing is only one of many meaning- and sense-making resources that people use for everyday communication.

A couple of years ago, I spotted this sign during a morning stroll, in Chungyuan, Taiwan.

Image credit: Sign courtesy of Li Wei.

Image credit: Sign courtesy of Li Wei.It got my attention because it explicitly violates the standard grammatical rules of Code-Switching, which say that function words such as be and possessive markers such as the English ‘s are not to be switched. A Code-Switching analysis would probably not go too much further than identifying the two Chinese characters at the top as meaning “today;” the Japanese character underneath them is the equivalent to the possessive marker “‘s”, and the two Chinese characters in the middle mean “fruit.” In fact, it may leave out the parts that are represented by drawing and the colours. But beyond the surface of the sign, there is so much to be read. The single Japanese character brings in the colonial history of Taiwan, which was occupied by Japan between 1895 and 1945, and the cultural identification of young people of Taiwan now with Japan. And the Japanese word for “watermelon” is pronounced as suika, which sounds very similar to the Chinese term shuikuo (in Wade-Giles) for fruit.

Linguistics theories tend to focus exclusively on conventional language, and exclude gestures, postures, facial expressions, spatial display, font style, etc—hence the divides between linguistic and non-linguistic features. As part of the process of conventionalization, sets of linguist codes get named as English, Arabic, or Chinese, for example. Gestures and spatial positioning can also be culturally specific and conventionalised, though it doesn’t normally happen in linguistic theories. Translanguaging wants to challenge the divides between the so-called “linguistic codes” on the one hand and the “non-linguistic” means of communication on the other; they are all part of the repertoire of meaning- and sense-making resources. Likewise, Translanguaging wants to challenge the divides between named languages and view them as different cultural conventions and some people are socialised into moving between and across these conventions in their everyday communication; these are the so-called “multilinguals.”

Image Credit: Sign courtesy of Li Wei.

Image Credit: Sign courtesy of Li Wei.Here’s another sign from the same shop, photographed and sent to me a little while after my visit to Taiwan by a student who heard me talking about Translanguaging. Compared to the first sign, the space for the characters for fruit is occupied by a cut out picture of pineapples. Instead of is, the English word cut is written, and a hand sign is added with the Chinese word for special price and the English word cut repeated. The hand sign itself has multiple indexes—usually understood as the victory sign in the west, a popular photography pose in East Asia expressing a feeling of happiness or cuteness, and a traditional Chinese gesture meaning to cut. A Code-Switching reading of these signs can, of course, reveal certain aspects of the juxtaposition of the different linguistic codes. But a Translanguaging reading has the capacity to much more of the social semiotics of such signs that transcend the boundaries between named languages and between linguistic and non-linguistic cues.

Featured image credit: Hong Kong Night by Annie Spratt. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Translanguaging and Code-Switching: what’s the difference? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers