2019, the year of the periodic table

The periodic table turns 150 next year. Given that all scientific concepts are eventually refuted, the durability of the periodic table would suggest an almost transcendent quality that deserves greater scrutiny, especially as the United Nations has nominated 2019 as the year of the Periodic Table.

These days it seems that physics gives a fundamental explanation of the periodic table, although historically speaking it was the periodic table that gave rise to parts of atomic physics and quantum theory. I am thinking of Bohr’s 1913 model of the hydrogen atom and his extension of these ideas to the entire periodic table. The Bohr model can only cope quantitatively with one-electron systems, and yet using a mixture of chemical and spectroscopic intuition, Bohr succeeded in stating the electronic configurations of many different atoms.

Soon afterwards, Pauli postulated that electrons possessed a “classically non-describable two valuedness,” which at the hands of others became misleadingly known as “spin.” The electron does not really spin, but has an intrinsic magnetism that is not attributable to any mechanical motion whatsoever.

Remaining for a further moment on the physics of the periodic table, one should also mention Schrödinger, and the wave-nature of the electron. It is a remarkable fact that by solving his wave equation for the hydrogen atom, Schrödinger found that three quantum numbers were required to specify the possible solutions. When Pauli’s fourth quantum number was added to these three it became possible to explain the overall structure of the periodic table. As is well-known, the possible lengths of the periods in the table—namely 2, 8, 18 and 32—come from the possible ways to combine the four quantum numbers for each of the electrons in an atom. This in turn suggests a further vindication of Prout’s hypothesis, postulated over 100 years earlier, that all the atoms are composites of the hydrogen atom.

Now let me now turn to chemistry and pick up the story. A little after Prout proposed his simple idea, Döbereiner discovered the first few examples of triads of elements whereby one of a group of the three elements has the average atomic weight among the three. This suggested an underlying regularity that connected completely different atoms.

The very existence of triads rests on nothing but chemical periodicity, the notion that approximate repetitions occur after regular intervals in an ordered sequence of elements. For example, the reason why chlorine, bromine, and iodine form a triad is the fact that there are an equal number of elements situated between chlorine and bromine as there are between bromine and iodine. It could almost be said that Döbereiner discovered periodicity 50 or so years before Mendeleev.

Many questions continue to be debated concerning Mendeleev’s 1869 discovery of the chemical periodicity, including whether he was the only discoverer. My personal view is that discoveries occur in a gradual evolutionary fashion and that they frequently occur in many places almost at once. The periodic table was independently discovered by at least six individuals over a period of seven years between De Chancourtois’ telluric screw of 1862 and Mendeleev’s mature periodic table of 1869.

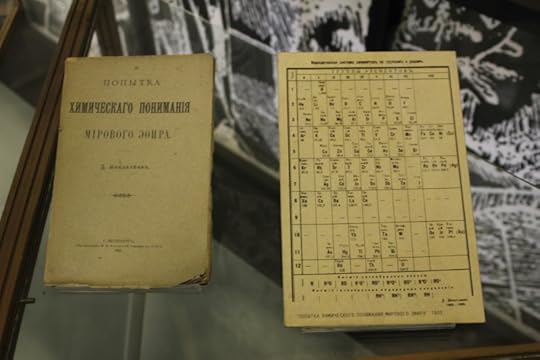

Image credit: “D. Mendeleev’s Periodic table from his book” by Newnoname. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: “D. Mendeleev’s Periodic table from his book” by Newnoname. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons.A surprising feature of the periodic table is the extent to which many aspects of it are still unresolved. There is little agreement as to what its optimal form should be, or indeed whether an optimal form even exists. The almost ubiquitous version is the 18-column wide table that displays the f-block elements as a kind of disconnected footnote. Some of us believe that the f-block is better shown incorporated into the main body of what now becomes a 32-column table.

A more radical alternative consists of the left-step table as first proposed in the 1920s by the French engineer Charles Janet. In this table, helium is relocated to the top of the alkaline earth elements on the basis of its having two electrons and so being analogous to elements that possess two outer-shell electrons. A second modification consists in moving the entire s-block, including helium, to the right hand edge of the table. This left-step table now shows every single period length as repeated, by contrast with the more traditional tables in which the first very short period of two elements appears just once. The new sequence of period lengths in the Janet table becomes, 2, 2, 8, 8, 18, 18, 32,32, a more mathematically regular sequence that is also more consistent with the Madelung rule that summarizes the order of orbital filling.

But the Madelung rule itself is a matter of some controversy since, for any given element, the rule only provides the order of filling for the s-block elements. On the other hand, the Madelung rule does genuinely yield the order of orbital filling as one moves through the periodic table, barring 20 or so anomalies starting with the atoms of chromium and copper.

The periodic table has endured many challenges in the course of its development. The first major crisis took place when the noble gases were first discovered at the turn of the 19th century. It first seemed as though there were no places to house these unexpected elements. Similarly, the sudden proliferation of isotopes seemed to pose a major problem for the periodic table. Both of these problems were successfully resolved. The noble gases were housed in a new column that is placed at the right hand edge of the table, at least in the conventional formats. In the case of isotopes, it was realized that the identity of elements was captured by the number of protons in the nuclei of their atoms or their atomic number. Separate isotopes of any particular element did not have to be separately displayed on the periodic table given that they share the same atomic number.

However, not all is well in the world of the periodic table. First, it is incomplete in a literal sense that new elements are continually being synthesized and taking their place at the table. Secondly, nobody knows where the periodic table will end. Some predict it will end with element 127 on the basis of a simple argument from relativity theory, while other more sophisticated calculations point to a higher value of 172 or perhaps 173.

Thirdly, and perhaps most serious of all, there is the looming threat of modifications to the behavior of atoms due to relativistic effects which cause some elements not to behave in the way that one might predict from the group that they fall in. If this trouble persists it may yet destroy the central tenet of the periodic table, namely the approximate repetition in chemical properties after regular intervals.

Featured image credit: “Air Force photo” by Margo Wright. Labeled for reuse with modification via Tinker Air Force Base.

The post 2019, the year of the periodic table appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers