Chris Dillow's Blog, page 57

July 20, 2017

Asymmetric policies

���We���ve got to reverse QE and do so quickly��� says Tim Worstall. I don���t want to take a view on that. What interests me instead is that reverse QE might be a misnomer, because central banks selling bonds doesn���t have the same effects as them buying bonds. ���Reverse QE��� is not simply QE with the opposite sign.

What I mean is that the first round of QE in particular worked (pdf) through two mechanisms. One was a portfolio rebalancing effect. The Bank���s buying of gilts forced yields down, and this helped reduced yields on equities and corporate bonds as investors rebalanced their portfolios towards those assets. The other was a signalling effect. QE signalled to everybody that the Bank intended for interest rates to stay low for a long time. This reduced gilt yields simply by reducing the expected path of short rates.

With QE, these two effects worked together. With reverse QE, however, they���ll work in opposite directions. Yes, central bank selling of bonds will tend to depress their prices and raise yields. But the signalling effect will work against this. Investors might interpret reverse QE as an alternative to rate rises ��� because if policy is being tightened via the portfolio rebalancing effect, it won���t need to be tightened so much via higher short rates.

The net impact of reverse QE is therefore unclear.

What we have here is an asymmetry. Policy works differently in one direction than it does in the other.

Which brings me to a more interesting question. How large is this set of asymmetric policies? I suspect it Is quite big.

Fiscal policy at the zero bound might be another example. If policy tightens, multipliers (pdf) might be large because there might be little reliable monetary offset; how true this is depends upon your view of the reliability of QE*. But if policy loosens, multipliers might be smaller because there is a monetary offset: rates can rise.

Brexit is another example. Having left the EU, we might not be able to rejoin it on the terms we currently enjoy: we might, for example, have to join the euro.

Another set of examples concern hysteresis effects. Simon says that austerity might have reduced trend growth by creating an innovations gap. Reversing austerity might not close this gap. It���s possible that memories of years of slow growth post-2008 will continue to depress animal spirits even under more sensible fiscal policy.

The Lawson boom of the late 80s might be an example of this. It led to higher inflation in part perhaps because the Thatcher recession had destroyed skills and industrial capacity. Reversing tight policy did not therefore undo the damage of that policy.

Other examples centre on cultural effects. To take a long-term historical example, freeing slaves did not fully reverse the damage of slavery, as its adverse effects are still with us.

I fear that inequality falls into this category. The IFS said this week that inequality has fallen. This might not, however, swiftly reverse the damage done by increased inequality in the 80s and 90s ��� for example, the reduction in trust and in productivity.

Perhaps top tax rates are another example. The cut in these in the 80s led to (or at least was associated with) a sense among the rich that they are entitled to their pre-tax incomes. It reduced tax morale ��� the rich���s willingness to comply with tax laws. And this in turn means that raising tax rates would lead to more tax-dodging, emigration or retirement than would otherwise have been the case. Reversing tax cuts might not therefore raise very much revenue.

Maybe you can think of other, better, examples from other fields.

My point here is that we shouldn���t assume that policy-making is a simple hydraulic process of pulling and pushing levers. Pulling a lever doesn���t always simply reverse the effect of pushing it. Bill Phillips Moniac model is perhaps sometimes a bad analogy. Instead, I prefer the wisdom which I associate with Joseph Schumpeter (although I can���t track down the source): ���If a man has been hit by a truck, you do not restore him to health simply by reversing the truck.���

* I think reliability is a key issue. Maybe there was a particular amount of QE the Bank of England might have done to offset fiscal austerity. But given the Bank���s inability to know this quantity precisely in 2010-11, a full offset was very difficult.

July 19, 2017

The economics of BBC pay

The BBC���s publication of a list of its best-paid talent has triggered many subjective views on who���s overpaid. But there���s another issue here, namely: how can we understand what���s going on?

The natural framework for doing so is a bargaining model. This says that pay depends upon just a handful of factors*:

- Fall-back options. For the BBC**, this is what it would get if it employed the next-best alternative to (say) Naga Munchetty rather than Ms M herself. For Ms M, it���s what she���d get if she worked elsewhere. Obviously, the better your fall-back option, the better you'll be paid, other things equal.

- The joint surplus. The is the pay-off to both parties of the match between the BBC and Ms Munchetty, relative to their fall-back positions. This pay-off isn���t necessarily wholly monetary. For the BBC, it might be the prestige of a quality programme, or the job security commissioning editors get from high viewing figures. And for the talent it can be the platform it gets; being on BBC Breakfast can be a springboard to getting onto Strictly, for example.

- Bargaining power. How much of this surplus can one extract for oneself?

Take, for example, Peter Capaldi, who earned less than ��250,000. This doesn���t seem much, given that the joint surplus is huge ��� Doctor Who is a worldwide hit ��� and Capaldi���s ability so great as to give him lots of outside options. But it���s more understandable, once we recognise two things. One is that the BBC���s fall-back position is strong: Doctors are replaceable and the format���s success doesn���t depend upon the actor ��� and that being the Doctor gives Capaldi a fantastic basis for negotiating his next job; it's wroth being temporarily underpaid for that.

Or take Alan Shearer. His ��400k+ wedge looks like he���s having a laugh. But it���s the result of his having a strong fall-back position. He could get big money from Sky or BT Sports; given the rubbish the latter employ, this is a credible threat. Or given his wealth, he could simply walk away: this is another example of a Matthew effect. This gives him a high wage. You might think this is offset by the BBC���s strong fall-back position: anybody can talk shit about football. This is not so. Few have the credibility as a pundit that comes from being the Premier League���s top scorer; BBC bosses evidently value that highly, and so have a poor fall-back position.

Or consider Helen Castor (as I often do). Based on talent, she should be high on the list. But she���s not. One reason for this is that highbrow history shows on BBC4 have a small joint surplus. Another is that she lacks a good fall-back; there are few good history programmes on other channels and Suzannah Lipscomb has bagged them.

I reckon the bargaining framework helps illuminate what���s going on. But there are (at least) four wrinkles:

- In many cases, the BBC���s fall-back position is weak, or at least it believes it to be so. The reason for this was pointed out by Marko Tervio. What���s scarce, he says, is not so much talent as proven talent. You might think you could do a good job of interviewing a politician live on air. But unless you���ve done so, you can���t prove it. And few people have done so. This means BBC bosses are scared to replace Andrew Neil or Eddie Mair ��� hence their big money. Similarly, some radio presenters are well-paid, because bosses doubt whether their replacements will get so many millions of listeners.

- Compensating advantages. As Adam Smith pointed out, differences in wages are often just compensation for other advantages. Breakfast presenters, for example, must be well-paid to compensate for having to get up so early.

- Comparisons matter. Our well-being depends not just upon our income but upon how much we get relative to others (pdf). This means that unless the BBC wants some of its presenters to look and sound miserable, it must pay them something like their colleagues, even if their objective talents don���t necessarily merit such rewards. Having decided to pay Alex Jones a good wedge, the BBC thus gives Matt Baker a fortune. (This doesn���t, however, seem to have worked in John Humphrys��� case).

- There���s an idiosyncratic element to bargaining power. Anybody who���s worked in investment banking knows that similar talents and circumstances co-exist with huge differences in pay. In particular, we know that ��� in least in some circumstances ��� women get worse (pdf) deals than men (pdf).

It is, therefore, a little odd that the BBC should refer to the list as payments for on-air talent ��� because talent is only one factor that determines pay.

* I'm drawing here on Ch 5 of Sam Bowles Microeconomics, one of the best economics textbooks

** I���m speaking loosely here. By BBC, I mean the specific BBC bosses who hire the talent, and their interests mightn���t be aligned with the corporation���s or the viewers���.

July 18, 2017

Facts, frictions & "mainstream" economics

John Rapley���s claim that economics has become a religion has kicked off another debate about the state of economics.

For me, there seems to be a presumption here which both sides seem to share but which I don���t ��� or at least that I don���t care about. It���s that economics is a canon of work which is taught to students and the outside world. However, I think of economics differently ��� as a box of theories, evidence and mechanisms which help me make sense of the world. What I care about is: what are the facts? And: how do we explain them? I don't much care what's orthodox or heterodox.

I���ll take an example from financial economics. We have a theory here ��� the capital asset pricing model ��� which predicts that riskier shares will on average out-perform safer ones, where risk is defined by a share���s covariance with the market (or beta). I used to believe this.

But there���s a problem with it. It���s false. We know this not because of methodological diversity but because of the facts. We have a body of evidence which shows (pdf) that less risky stocks out-perform riskier ones ��� in flat contradiction to the CAPM*. I stress here that it���s the body of evidence that matters. Single studies are prone to not being replicated, but the defensive anomaly has been found in different data and with different measures**. And the CAPM���s failure is now accepted even by mainstream economists: Eugene Fama and Ken French have written that it ���has never been an empirical success���.

Now, maybe the CAPM is still taught uncritically in some business schools and universities. To the extent that it is, Rapley is right. But I don���t really care. The purpose of university is to acquire credentials and a grounding for later learning rather than to get a complete education.

What I do care about is why the CAPM is wrong. A big part of the story lies in market imperfections.

Researchers at AQR Capital Management point out (pdf) that many investors cannot borrow and lend freely as the CAPM assumes. They express their bullishness not by borrowing to buy the market portfolio but by buying high-beta stocks ��� those which are in effect a geared play on the market. This causes such stocks to be over-priced on average, because most investors are usually bullish; they know about the equity premium. The counterpart to this is that defensives are under-priced.

A second imperfection is that short-selling is a damned sight harder in practice than in theory. Even if you���re right in the long-term (a few weeks) that a stock is over-priced, margin calls can wipe you out in the near-term. This is especially true for volatile stocks.

Such frictions mean that mispricings persist. Again, we know this not because of abstract theorizing but because economists have done the hard yards of seeking the facts. David McLean and Jeffrey Pontiff show that only around half (pdf) of mispricings in the US are eliminated after they���ve been discovered. The proportion is even smaller in Europe.

What does all this tell us? In part, it leads me to side with some ���heterodox��� economists***. Market frictions such as borrowing and short-sales constraints (pdf) are not minor quirks that can be ignored until later in one���s studies. They are instead part of the essential nature of the beast which generate the most important thing in economics ��� facts.

But I also sympathize with the ���orthodoxy���. Flaws with ���mainstream��� theory are to be found ��� in the first instance - not by armchair theorizing but by gathering facts.

Now, you might object that financial economics is a minor tributary of economics that nobody much cares about. For me, this is its appeal. Macroeconomics is, for many people, so tied up with their political passions that progress is more difficult.

* This isn���t the only evidence against the CAPM: there���s also momentum, among other things.

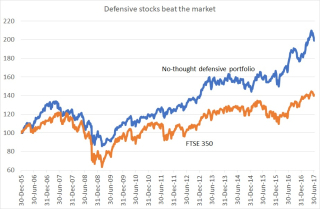

** In the day job, I���ve ran my own real-time test. I���ve simply taken an equal-weighted basket of the 20 lowest-beta stocks in the FTSE 350 and measured their performance. My chart shows that they have hugely beaten the FTSE 350.

*** The scare quotes are because I don���t care about the distinction between heterodox and orthodox. What matters is what explains the facts.

July 17, 2017

On BBC bias

Much as I like this piece by Ian Leslie, there���s something I disagree with. It���s this:

Almost as a blanket rule, don���t bash the BBC���The BBC is about the only thing standing between post-Brexit Britain and a Trump-style reality-free culture war.

He has a point, insofar as a lot of BBC-bashing is just narcissistic whining that the corporation doesn���t echo one���s own prejudices. Nevertheless, I fear there is a problem with the corporation.

One fact tells us this - that the public are horribly wrong about many basic facts. Of course, this isn���t wholly or even mainly the BBC���s fault. But such massive ignorance should alert us to the possibility that the country���s most powerful broadcaster isn���t fulfilling its purpose of informing its viewers and listeners.

A big reason for this, I suspect, is a policy of ���due impartiality��� which gives us ���he says, he says��� reporting, and hence ���balance��� between truth and lies, and a failure to report what the experts' consensus is. Paul Krugman has called this ���views differ on shape of the planet reporting.��� Even within the BBC, there is disquiet at this. Norman Smith, the BBC���s assistant political editor, has said:

There is an instinctive bias within the BBC towards impartiality to the exclusion sometimes of making judgment calls that we can and should make. We are very very cautious about saying something is factually wrong and I think as an organization we could be more muscular about it���.I suspect we, we hold back from making those sort of calls, and I do think that, potentially, is a disservice to the listener and viewer.

This has been echoed by a report commissioned by the BBC Trust, which says (pdf):

The BBC frequently presents different sets of statistics put forward by those on either side of an argument. Audience research, and our own discussions, showed considerable frustration with this way of presenting statistics and effectively leaving the audience to make up its own mind. The BBC needs to get better and braver in interpreting and explaining rival statistics and guiding the audience. (Emphasis in original)

This can contribute to ignorance. Years ago, Alexander Cockburn complained that such balance meant that ���since everything can be contradicted, nothing may be worth remembering.���

This isn���t just a disservice to the viewer*. It���s a disservice to democracy.

Yes, the BBC can point to Reality Check and More or Less as counter-examples of what I mean. But these don���t have anything like the prominence of its main news programmes.

The general problem here is to pay too much attention to talk ��� especially Westminster-based talk ��� and not enough to ground truth. It's this that also gives us mindless speak your branes shows like Question Time or Sunday Morning Live. I don���t care what some random guy thinks. What I want to know is the truth, or at least facts. Of course, there���s a place for values, but these should be the considered opinions of philosophers, not of rentagobs.

I suspect this is why the BBC appeared biased against Corbyn. It���s not that its reporters were consciously anti-Corbyn, but that their attitudes to him were coloured by his unpopularity among MPs ��� and this led them to under-estimate his popularity among Labour���s grassroots and his ability to campaign outside Westminster. Equally - and just as misleadingly - George Osborne was spoken of as a believer in devolution because he spoke about the ���Northern Powerhouse��� but in fact the ground truth was that his cuts to local government meant he in effect centralized power.

This prioritizing of talk over ground truth has leads to at least two distortions.

One is that it tends to select politicians for fluency, (over)-confidence and the appearance of matiness, which can lead to a downgrading of other virtues such as grasp of policy, good decision-making or managerial ability. This bias is especially great given that interviewers seem to regard it as their job to make a fool of politicians, rather than to elicit information about policy and values.

The other is that it leads to a bias against emergence. Issues that politicians talk about - and which they give the (misleading) impression of controlling ��� get more attention than more important outcomes of emergent processes. Our biggest economic problem is stagnant productivity, not the ���nation���s finances��� ��� but you���d never have inferred this from the BBC���s coverage.

What I���m saying here shouldn���t be surprising. Every profession ��� yes, including economists ��� has its own perspective on the world which can be distorting as well as illuminating: it���s called deformation professionelle. Political journalists are no more immune to these than anybody else.

Now, I don���t intend this to be general BBC-bashing. A lot that the BBC does is brilliant. But this doesn���t include its political and economic reporting.

It���s said that the purpose of a liberal education to teach people the best that has been thought or said, or is being thought and said. Whilst this is true for at least some of the BBC���s output, it is not true of it political journalism.

* The problem here isn���t confined to political reporting. Ben Goldacre says that uncritical reporting of Andrew Wakefield���s claims about a link between the MMR vaccine and autism contributed to a decline in vaccinations in the early 00s.

July 16, 2017

My Brexit dilemma

It���s become common to demand that Labour take a clearer stand against Brexit. Such demands, I fear, forget Wittgenstein���s point ��� that a clear picture of a fuzzy thing is itself fuzzy.

I say this because there is a genuine dilemma here. On the one hand, it���s clear that Brexit will be a horrible, impoverishing, mess. But on the other hand, it���s what the voters want.

Many, of course, don���t feel this dilemma. Those who regard Brexit as a good thing in itself ��� an assertion of British sovereignty - are willing to bear the economic cost (or are wilfully blind to it, or hoping to shift it onto others).

And on the other side, some centrist-managerialists are relaxed about ignoring voters��� preferences.

Those of us who regard empowering people as a central plank of leftism don���t, however, have this luxury. This, I think, makes Labour���s apparent confusion over Brexit understandable; it���s the product of a genuine conflict of values. Maintaining this ambiguity is, I think, a least-bad option: I prefer to call it ���constructive ambiguity��� rather than ���weaponized vacuity���, to use Ian Dunt���s phrases.

Brexit is above all a Tory mess. Labour���s right to want to avoid it as far as possible.

You might think a solution to this is to want a second referendum. It���s perfectly possible that, once they get a clear sight of what real Brexit actually means, voters will reject it.

Personally, I���m not sure. The first referendum was a despicable, dishonest spectacle. There���s no reason to suppose a second would be better. Quite the opposite. Brexiteers might be more desperate next time around: backfire effects and asymmetric Bayesianism warn us that partisans don���t change their minds when confronted with discorroborating evidence, but rather double down and become more dogmatic.

What���s more, a Remain win would not kill the issue. It���s quite possible that some sort of European ���crisis��� in the future will trigger claims from Brexiteers that things have changed to justify a third referendum. We���d then have a hokey cokey policy towards the EU: in, out, in, out, shake it all about. I find this a horrible prospect. Blair is bang right to say Brexit is a ���massive distraction���. It steals cognitive bandwidth from more important matters. I���d like to see the issue killed for good, and I don���t think a second referendum would achieve this.

There is, though, perhaps a bigger problem here. Brexit has highlighted some fundamental problems with politics. I���m not thinking here merely of the fact ��� important though it is ��� that we lack the state capacity to manage the process. I fear instead that we lack the tools to deal with the issue.

What I mean is that many political issues are matters of degree: more or less government, more or less equality, more or less freedom and so on. Politics is then a matter of tweaking dials a little.

Brexit, though, is different. It���s a binary issue: in or out. And it seems we can���t settle this matter. This might be because the stakes are incommensurable - sovereignty versus (some) prosperity ��� and as Alasdair MacIntyre said, we have no way of weighing such claims against each other*. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that political partisans are fanatical narcissists.

Perhaps this leaves just one hope ��� that Brexit will fade as an issue only when its supporters, being older than average, die off. To paraphrase Max Planck, civilization progresses one funeral at a time.

* I confess to not understanding the appeal of Brexit here: Brexiteers have never satisfactorily told me what I will be free to do after Brexit that I can���t do so now. But this might be because I have too prosaic a mind.

July 14, 2017

On contradictory risk attitudes

A few days ago, a friend said she was worried that her daughter had been kidnapped by zombies because she hadn���t texted her as promised. I replied that this was an example of base rate neglect; the chances of a girl forgetting to text her mum are much higher than of her being kidnapped by zombies, even in London.

And then Bryan Caplan says that parents in Virginia should not worry that their sons will be imprisoned for normal teenage behaviour because of the state���s stupid laws because the chances of them being so are remote.

As statisticians, Bryan and I are bang right. As humans, however, we���re not. It is perfectly reasonable for parents to worry about their children, even if the statistics say otherwise. It���s easy to see how such a habit might have evolved. The stone-age mother who feared that every rustling of the trees hid a sabre-toothed tiger and who ran away with her child had children who grew to adulthood and who passed on risk-averse habits. The statistically literate mother who thought it was just the wind was right 99 times in 100, but her child was dead the 100th and became an evolutionary dead-end.

This erring on the side of caution is not, however, a universal trait. Many safety-obsessed parents voted for a reckless gamble on Brexit. The point broadens. We have different attitudes to risk in different domains: some people who enjoy risky sports avoid financial risk and vice versa; I never go into a bookie���s but have many times my salary invested in equities (at least in the winter); and many of us buy insurance but take gambles in other ways.

It���s not clear that such differences can be explained by the conventional textbook theory of risk aversion -which, as Matthew Rabin and Richard Thaler have pointed out (pdf), doesn���t make much sense anyway.

Instead, I suspect that what happens is that we code gains and losses differently in different ways; this, I think, is the big message of this recent paper (pdf) by Michael Woodford and colleagues.

In thinking about their kids, parents focus heavily upon worst-case outcomes even if these are statistically improbable: I���m not sure this is wholly due to the availability bias Bryan describes but to a more reasonable desire to keep them alive. But in thinking about economic policy choices, those same parents might think: what have we got to lose?

Similarly, I don���t bet on horses because the coding doesn���t seem right to me: so what if I occasionally win ��100 or even ��1000? Such sums won���t change my life much but similar-sized losses would make me feel guilty (I haven���t wholly escaped my Methodist upbringing). Betting on shares, however, codes better for me. This isn���t because I believe there���s a big equity premium, but because the reasonable chance of being able to retire early appeals whilst the downside ��� working longer ��� is just about tolerable.

These differences in coding mean that, contrary to conventional theory, money is not fungible. Our house being burgled is not just different in degree from losing ��100 on the gee-gees, but is different in kind. (This inference is strengthened if we throw mental accounting into the mix, as we should).

Maybe attitudes to risk can���t be reduced to simple maths but instead depend upon our imaginations, which vary from context to context.

What���s more, in the real world it might be tricky to distinguish between perceptions of risk and tastes thereof. Is the mother worrying about her child really mistaken about numerical probabilities, or is she just very risk averse? What looks like a mistake might actually be a useful way of protecting the child.

I guess the point I���m groping towards is that this is one arena in which there is a gulf between conventional economics and real human beings ��� and perhaps the humans aren���t wholly wrong.

July 13, 2017

Ideologue managerialists

The confession by Elizabeth Campbell, the new leader of Kensington Council, that she has never been in a high-rise flat has led to allegations that she is out of touch, and is seen as confirmation that rich and poor are ���two nations between whom there is no intercourse and no sympathy; who are as ignorant of each other's habits, thoughts, and feelings, as if they were dwellers in different zones.���

There is, though, another inference. It starts from the fact that Ms Campbell was for years both in charge of the council���s children���s services and on the board of Kensington and Chelsea���s TMO. You���d imagine that either role would require her to know a little of the reality of life in a council flat.

That Ms Campbell escaped such reality is not an idiosyncratic failing. Instead, she embodies a feature of today���s management described by Robert Protherough and John Pick in 2002:

The achievement of modern managerial goals generally involves a high degree of mental abstraction, but little direct contact with the organization���s workers, with the production of its goods or services, or with its customers and users. As the admirable Professor Mintzberg says���most modern managers are ���capable of manipulating symbols and abstractions but ill-equipped to deal with real decisions involving people.��� (Managing Britannia, p32)

The danger of this was pointed out 42 years ago by Kenneth Boulding ��� that bosses will become out-of-touch:

All organizational structures tend to produce false images in the decision-maker, and that the larger and more authoritarian the organization, the better the chance that its top decision-makers will be operating in purely imaginary worlds.

This is no mere theoretical possibility. It���s exactly what Chilcot says happened with the Iraq war: ministers didn���t know the ground truth. And we���ve seeing the same thing with Brexit; Brexiteers wibble about mental abstractions such as sovereignty but are ignorant of nitty-gritty ground truth of how exactly to negotiate the countless minutiae of Brexit.

This leads me to sympathize with John Gapper���s lament that politicians lack practical knowledge of science and industry. What���s most missing though, is the scientific method, the essence of which is the collision between theory and fact. If you make no effort to discover ground truth (or in Ms Campbell���s case, 15th floor truth) you���ll never test your beliefs against the facts and you���ll never learn.

And this is just what happened. Blair���s war in Iraq wasn���t so much a moral failure as an intellectual one; he failed to learn not just the messy truth about Iraq but also the vast evidence on cognitive biases. Likewise, Brexiteers failed to learn from Blair that it���s not a good idea to embark upon a risky foreign policy without a detailed plan or strong evidence.

Herein lies what so appalling about Ms Campbell. In being wilfully out of touch, she is actually typical of so many policy-makers. Today���s dangerous ideologues are not Marxists but managerialists of all parties who are constitutionally unable to learn.

July 12, 2017

The centrist crisis

Alex Massie wonders when the Corbyn bubble will burst. Phil gives us a reason why it might not do so soon ��� because Labour���s right ���have no ideas, no clue, and no plan to respond to the situation we find ourselves in.��� Granted, many of us have under-estimated Corbyn, but this shouldn���t detract from the fact that his popularity within the party owes a lot to the lack of alternatives ��� to the fact that centrism is in crisis.

This crisis has a material base. Centrists can���t adequately answer Janet Jackson���s question: what have you done for me lately? Ten years of falling real wages and productivity tell us that centrist policies and institutions have failed.

The fact is that centrist policies (of all parties) are now largely out-of-date. Trying to placate bond markets made sense when real yields were 4%, but isn���t so important now they are minus 1%. Work was a route out of poverty when jobs were well-paid, rents were reasonable and in-work benefits decent ��� but this is less the case now. And ���education, education, education��� isn���t so effective a strategy now that, as Sarah O���Connor says, ���people do not feel middle-class any more��� because younger, educated people lack ���homes, security, prospects��� (and, I���d add, job satisfaction and professional autonomy.)

What���s more, the longstanding blindspot of centrists is now an insuperable handicap. I mean, of course, their failure to appreciate the importance of inequalities of power.

In the 90s, New Labour focused upon income inequality between the 90th and 10th percentiles. Today, though, the inequality that matters most is that between the 1% or even 0.1% and the rest of us. Parasitic managerialism caused the financial crisis, greatly contributed to the productivity slowdown and is now wreaking damage to universities. New Labour���s fetishizing of ���leadership��� and targets helped to legitimate this.

As we saw in yesterday���s Taylor review, centrists have no answer to this problem. (In fact, they don���t even see the problem). Taylor���s polite request to bosses to play nicely ignores what Ben calls ���the extreme asymmetry of power between the worker and employer in the typical UK workplace.��� What centrists are missing is that elites have too much power and too little competence*.

I���m not sure that Corbynism is an adequate answer to this. But Corbynites at least see that there���s an issue here. Until centrists catch up, they���ll deserve to remain a marginal force both politically and intellectually.

* In this context, Lord Adonis's complaint that tuition fees have boosted Vice-Chancellors' pay more than teaching quality and Dominic Cummings' view that Brexit might turn out to be a mistake are similar examples of centrists' failures - an inability to see that if you entrust money and power to elites, they will be misused.

July 11, 2017

The Taylor Review: 1990s answers to 2010s problems

For me, the Taylor Review (pdf) of working practices is frustrating. There are some good things about it, not least of which is it���s mere existence. Anything that brings the hidden abode of production into public view, and draws attention to the ground truth of working lives, is to be welcomed. I also welcome its demand that ���workers must have a voice���, its pointing out the hidden unemployment that is economic inactivity, and the insecurity evident in labour market flows data. I also like this:

People who have less autonomy over what they do at work tend to report lower wellbeing rates. The same is true of those people working in high-intensity environments. As such, allowing workers more autonomy over the content and pace of their work amongst other things can lead to higher wellbeing for these individuals and increased productivity.

There is, though, a big problem with it. There���s a massive gap between diagnosis and remedy. This (p26) is bang right:

The key factor is an imbalance of power between individuals and employers. Where employers hold more power than employees, this can lead to poorer working conditions and lower wage levels.

How then can Taylor say this?:

The best way to achieve better work is not national regulation but responsible corporate governance, good management and strong employment relations within the organisation.

Surely not. The best way to achieve better work is to ensure that employees have the power to reject oppressive jobs and choose good ones. This requires that they have outside options ��� something to walk away to.

And yet Taylor doesn't mention the things that would increase these options and so empower workers. These include disempowering monopsonies; a more generous welfare safety net (such as a citizens income); stronger trades unions; and macroeconomic policy that creates plentiful jobs.

Rather than consider ways to empower workers to make their own choices, however, Taylor focuses upon top-down managerialist policies such as (quite mild) changes to law and taxation and ways to ���incentivise employers��� to use fairer and more responsible models.��� Workers it seems, are not so much active subjects as passive objects of policy onto whom working practices for good or ill are imposed.

In fact, two obvious ways through which workers might become more active subjects are not mentioned: trades unions and co-ops.

Instead, what we have is unreflective managerialism. We see this in his attitude to productivity. He writes:

Achieving improved productivity will rely on a number of things, not least investment in infrastructure, improved skill-levels, more technological advancement and delivery of the modern industrial strategy.

What���s missing here is the need to improve management. As Bloom and Van Reenen have shown (pdf), there is ���a long tail of extremely badly managed firms.��� Taylor comes close to seeing this, but thinks the answer lies in exhorting them to do better. Management���s right to manage is unquestioned, and alternative corporate forms ��� such as genuine worker control rather than a little say ��� are largely ignored.

In this sense, there���s a paradox about the report. On the one hand, there���s a focus upon new changes in the workplace ��� the rise of platform employers, the gig economy and new technologies. And yet on the other hand, Taylor is stuck in the past. There���s no acknowledgement that managerialism might be the cause of stagnant productivity and bad working conditions, and no clue that Brexit and Corbynism are both popular reactions against elite control.

What Taylor offers, then, is 1990s solutions to 2010s problems. Which isn���t good enough.

July 10, 2017

On Matthew effects

Claer Barrett in the FT writes that ���people with little cash to spare can nevertheless be hugely profitable for the financial services industry.��� This is true. People who are short of money are often desperate to borrow and so willing to pay high interest rates to loan-sharks, payday lenders or car finance companies. If you lack negotiating power, you���ll get a bad deal.

This is an example of the Matthew effect:

For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance: but from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath.

We see this effect in other contexts too:

- The struggle to get by on a low income steals cognitive bandwidth and so makes people more likely to make mistakes, such as borrowing at too high an interest rate. Eldar Shafir says: ���if you live in poverty, you���re more error prone and errors cost you more dearly ��� it���s hard to find a way out.���

- Youth unemployment has a scarring effect: it reduces incomes even years later. A temporary misfortune early in life can therefore be a longlasting handicap.

- The poor are often so desperate that they try to gamble their way out of poverty. Prospect theory tells us that people are risk-seeking when they���ve become short of cash. It���s no accident that there are so many bookmakers in poor areas. As Father Michael said in the brilliant Broken: ���If you���ve only got a fiver to last you the rest of the week, it makes eminent sense to gamble it���. Bookies, he continued, are ���feeding off our poverty.���

- Rented property is means whereby cash is transferred from people who are capital- or credit-constrained and unable to get a mortgage towards people who are not so constrained.

- Thomas Piketty���s famous r>g formula (that the return on wealth exceeds the growth rate) says that those that hath shall be given more, and so inequality will tend to increase, barring major disturbances.

- The rich pass on advantages to their children. This isn���t simply because they pass on education and skills. Research by Paul Gregg and colleagues shows that intergenerational mobility in the UK and US is low even controlling for educational attainment.

All of this means there���s some truth in the old clich��: the rich get richer, the poor stay poor.��� Although the ONS says that the UK has a relatively low rate of persistent poverty, I suspect this is the result of people shifting to just above the poverty line rather than into great fortune. Other ONS evidence (pdf) shows that half of those who were in the bottom income quintile in 2010 were still there in 2014, and that a further quarter were in the next quintile, implying that only a quarter made it into the top 60%.

You might think all this is trivial. Maybe. But there���s another arena in which the Matthew effect operates: capital-labour relations. Exploitation, thought Marx, arises because the worker���s poverty puts him in a weak bargaining position. He ���has no other commodity for sale��� than his labour-power and in ���bringing his own hide to market���has nothing to expect but ��� a hiding.��� This is still, generally, true. Yes, there are some instances whereby labour can exploit capital (such as top-league footballers or chief executives) but these are rare exceptions. In most cases, it���s capital that has bargaining power and labour that doesn���t, and this gives us another Matthew effect.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers