Chris Dillow's Blog, page 53

October 7, 2017

Capitalism's bad incentives

Martin Wolf writes that successful leftism ���must recognise the crucial role of incentives in shaping human behaviour.��� This is correct. I���m not sure, though, that it is a big argument against Corbynism. This is because actually-existing capitalism itself contains many dysfunctional incentives ��� ones that constrain innovation and encourage rent-seeking - and Corbynism offer the hope of reducing some of these.

One such bad incentive is that high inequality gives the rich stronger incentives to protect their privilege by investing in methods which keep or increase their share of the economic pie without much increasing it. Sam Bowles and Arjun Jaydev show that unequal countries employ more ���guard labour��� ��� policemen, security guards, supervisors and so ��� than egalitarian ones. They say:

A significant portion of an economy���s productive potential may be devoted to the exercise of power and to the perpetuation of social relationships of domination and subordination.

A similar thing applies to innovation. Capitalists have incentives to invest in power-biased technical change ��� devices such as CCTV, Worksnaps or tachographs that help bosses monitor workers. Such technologies reduce the need for efficiency wages and so boost profits. But it���s not clear they are good for aggregate output.

Also, capitalists have incentives to stifle competition and to lobby for protection. Bank subsidies, corporate welfare such as some PFI contracts and intellectual property laws that stifle innovation are the result.

There���s another class of bad incentives under capitalism ��� those that arise because of imperfect monitoring of CEOs by outside shareholders or of underlings by bosses.

The former case can lead bosses to divert (pdf) their efforts to tasks that shareholders can easily monitor ��� such as cutting costs or manipulating short-term earnings numbers ��� whilst neglecting perhaps more important tasks such as promoting good corporate culture. This can lead to widespread criminality: Luigi Zingales and colleagues estimate that around one-in-seven companies engage in fraud.

It can also lead to the accumulation of cash piles and under-investments or to bad investments (RBS���s takeover of ABN Amro destroyed billions of pounds of wealth) as bosses aren���t properly monitored by shareholders.

Within the corporation, imperfect monitoring can cause bosses to hire underlings who resemble themselves, which generates groupthink and the Dilbert phenomenon (pdf).

Agency failure also allows a few lucky mediocrities to get big money, thus entrenching inequality. As Marko Tervio has shown, what���s scarce in many industries is not so much talent as proven talent. Employers would rather stick with known quantities who are just good enough rather than take a risk on unproven but potentially brilliant people. The upshot is mediocre management and stagnant organizations.

And all this is before we come to the financial sector. Here, Anat Admati has shown that implicit subsidies, shareholders��� desire for a high return on capital and the favourable tax treatment of debt finance have encourage excess leverage. She says (pdf):

In banking, the public interest in safety conflicts with the incentives of people within the industry. Protecting the public requires effective regulations because market forces fail to do so.

Bjorn-Christopher Witte offers a variant of this. He shows that fund managers are sometimes incentivized to be lucky risk-seekers rather than genuinely skilled. He says: ���Intense competitive pressure generates risk-seeking behavior and diminishes the predominance of the most skilled.��� For example, in the tech bubble of the late 90s managers who thought boo.com was a great stock attracted fund flows and big bonuses whilst knowledgeable ones like Tony Dye lost their jobs.

Now, I���m not saying that these bad incentives will bring down capitalism or that they are all eliminable: there is a great deal of ruin in a nation. They do, however, raise an important possibility ��� that there is abundant room for a leftist government to consider alternative governance structures that reduce agency problems and produce better incentives. As John McDonnell notes, such structures might (pdf) well include more cooperatives, as these give control to workers who have both skin in the game and local knowledge of particular working practices.

We shouldn���t generalize about the precise form such coops will take, as they���ll vary from firm to firm. Whether incentives work well or not is a matter of precise market microstructure, not windy talk. In this sense, socialism is an exercise in applied transactions economics.

Martin is sniffy about Corbyn���s promise to ���transform Britain by genuinely putting power in the hands of the people���, but I���m not sure he should be. Such a transformation might be a way of improving the incentives which he rightly believes are so important.

October 5, 2017

The Tories' structural crisis

Phillip Hammond���s speech to the Tory conference this week contained an interesting omission. He spoke of ���35 years in which we have seen real living standards almost double in this country.��� What he omitted to say was that all that growth came before 2007. GDP per head now is barely higher than it was then, and real wages are lower.

This reveals something ��� an inability of the Tory party to confront the modern world. Hammond just couldn���t admit to the realities of capitalist stagnation.

In this, of course, Hammond is not alone. We should see his speech alongside Amber Rudd���s willful inability to understand the internet, Johnson���s recitation of Kipling, and Rees-Mogg���s irrelevant invocation of Crecy and Agincourt. All are examples of the Tories being much more comfortable in the past than the present. Brexit, of course, is another example of this. For every Tory who sincerely regards this as a means of transforming the UK into an open global trading nation, it is for many more an effort to return us to a pre-immigration era.

All this nostalgia contrasts with the fact that the truly successful parties of post-war Britain have been forward-looking. Think of Attlee���s talk of building a ���new Jerusalem���; Macmillan���s embrace of decolonization and a mixed economy; Wilson���s ���white hot heat of technology���; Thatcher���s efforts to improve industrial relations so the UK could compete in a global economy; and of course Tony Blair couldn���t open his mouth in the 90s without talking of modernization.

In this sense, not only are the Tories not a party of government, they are barely even an opposition in waiting. They are just a small group of pensioners out of touch with the country.

How did they get themselves into this mess? I don���t think it���s simply because so many are so thunderingly mediocre: Theresa May���s ���burning injustice��� speech on becoming PM demonstrated some awareness of the challenges we face.

Instead, their problem is a structural one. Any serious attempt at modernizing the economy would alienate the party���s client base. As Richard Seymour says:

They no longer have any idea how to administer capitalism. No viable long-term growth strategy avails. They can't address the financial sector without hurting their allies in the City. They can't address the crisis of productivity and investment without more state intervention than they're willing to accept. They can't address the housing crisis or the precarious debt-driven economy without harming the interests of home owners.

In this context, speculation about the Tory leadership is irrelevant; it���s just another example of imbecile leadershipitis that disfigures British thinking not just about politics but business and sport too. The party���s crisis is much deeper than that.

October 3, 2017

Hammond's weak defence of markets

Philip Hammond said yesterday that the Tories must try to champion the market economy. This won���t work.

For one thing, Labour is not really challenging the market economy. Aditya is right to say it is offering ���moderate social democracy��� capitalism, of a kind that Angela Merkel would know.��� Labour���s nationalization plans focus upon those industries where it believes markets are not working. By all means criticize their diagnosis or remedy, but hyperventilating about them overthrowing the market economy is just stupid. Nationalizing the railways will make us resemble not Venezuela but Germany - and even the most fanatical Brexiter shouldn't panic about this.

There���s a further problem. It���s that mainstream Tories are not full-blooded free marketeers. In the labour market, they have raised the minimum wage and support immigration controls. In the housing market they favour planning restrictions that stop new building and Help to Buy, measures deplored by serious free marketeers. And there are some markets many Tories want to suppress, such as in sex and recreational drugs. Nor is there anything new about all this. As BBC4���s documentary on Friday reminded us, the Thatcher government���s supposed support for free markets and entrepreneurs didn���t stop it repressing pirate radio stations*.

Of course, you might reply that such restrictions are needed because free markets are not always a good thing. That���s entirely reasonable. But it carries two costs.

One is that it means you can���t use Hayek���s defence of free markets:

Since the value of freedom rests on the opportunities it provides for unforeseeable and unpredictable actions, we will rarely know what we lose through a particular restriction of freedom���.when we decide each issue solely on what appear to be its individual merits, we always over-estimate the advantages of central direction. (Law, Legislation and Liberty, vol I p56-57)

The second is that it means the difference between Labour and the Tories is not a matter of principle but of empirics: to what extent is any particular market working well, and if it isn���t what is the best remedy?

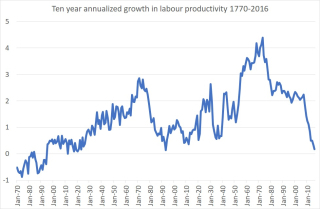

Which raises a further problem. Hammond doesn���t grasp the severity of our economic malaise. His claim that ���our economy is not broken: it is fundamentally strong��� reminds me of Monty Python���s Black Knight protesting that the loss of his arms was ���just a flesh wound.��� Ten years of stagnant real wages and the worst productivity performance since the start of the industrial revolution tell us that the economy is indeed broken. Windy talk about the market economy won���t fix it. Pretending that the economy is basically fine merely entrenches the impression that the Tories support only the most decadent sections of capital: landlords, rent-seekers and parasitic finance.

* The fact these were run by many black people was, no doubt, just a coincidence.

October 2, 2017

The lesson of the 70s

The Tories have a new line of attack on Labour ��� that they would take us back to the 1970s, as Hammond alleged this morning (2���19��� in). This raises the question: what was so bad then?

It���s not that wages did badly. Bank of England data show that they rose 22.7% between 1970 and 1979 after adjusting for RPI inflation. That���s substantially better than in the last ten years.

Nor, really, was the problem that much of industry was state-owned. True, it was. But most Tories at the time didn���t see this as a massive problem. As the Institute for Government has pointed out (pdf), the 1979 Tory manifesto ���barely mentioned��� privatization and the privatizations of the early 80s were seen mainly as revenue raising measures rather than as a deliberate means of expanding the market economy: that rationalization only followed later.

Nor even is it that the 70s saw high personal taxes on the rich. They did. But these continued well into the 80s. It wasn���t until 1988 that the top income tax rate was cut from 60%. If John McDonnell keeps his word, the top tax rate under a Corbyn premiership will be lower than it was for most of Thatcher���s.

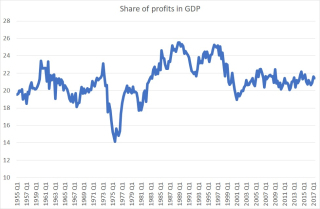

Instead, there���s another reason why Tories in particular regard the 70s as a period of crisis. It���s because it was ��� for profits. The share of profits in national ��� and also the rate of profits ��� slumped in the mid-70s. Not unrelatedly, so too did the share of the top 1%.

The reasons for this are discussed well in Marglin and Schor���s The Golden Age of Capitalism. Essentially, the long boom led to rising wage demands*, slower productivity and a spike in oil prices. Inflation ��� which people remember as the hallmark of the 70s ��� was the product of this. Workers wanted higher wages, capitalists wanted higher mark-ups and this led to higher prices. As Wendy Carlin and Sam Bowles say ���inflation arises from conflicts among economic actors, when they are powerful enough that their claims on goods and services are inconsistent.���

From this perspective, the true achievement of the Thatcher government was not so much to shrink the state as to weaken working class power and hence restore the conditions necessary for profitability.

Now, you might think there that what I���m saying is that the crisis of the 70s was a rich man���s problem.

No. Falling profits caused a sharp fall in capital spending. Had profits not recovered, it���s likely that capital spending would have fallen further and so growth would have been consistently weak and unemployment high. In this sense, low profits in a capitalist society are everybody���s problem.

This is why the slump of the 70s matters. It suggested that the full employment and rising wages of the Golden Age were unsustainable. Yes, Thatcher rescued capitalism, but at the expense of the misery of unemployment for millions.

In this sense, though, it is dangerous for Hammond to remind us of that period. We can read the 70s not just as evidence that social democracy is doomed to fail, but as evidence that the demands of capital and the demands of workers are, ultimately, fundamentally irreconcilable. As I said, in this sense it is he rather than McDonnell that is the Marxist.

* Of course, high wages in themselves don���t squeeze profits if they are returned to capitalists as workers spend those wages. In the 70s, though, this didn���t happen in part because households��� savings rose.

Another thing. In his interview with Nick Robinson this morning, Hammond said: ���Since 1979 when Britain turned its back on the policies of Corbyn and McDonnell���living standards in this country have doubled.��� By one obvious measure, this isn���t right. GDP per head has risen only 85% since 1979Q2. What���s more, GDP per head since 1979 has risen by only 1.6% per year, compared to a rise of 2.6% per year between 1955 (when current data began) and 1979. By this measure, turning our back on the policies of Corbyn and McDonnell led to slower growth.

September 29, 2017

The impact bias against Labour

This week���s prize for an epic lack of self-awareness goes to Philip Hammond, who told us that a Labour government would lead to ���a collapse in business investment and a crash in the value of the pound, causing a shockwave of inflation���.

Even if he has a point ��� which he hasn���t ��� this provokes the reply: how will we tell the difference from a Tory government?

The Tories have given us not one, not two but three of the worst economic policy errors of modern times: austerity; the vote to leave the EU (which was due in part to austerity); and then the pursuit of a hard Brexit. They have set the bar for economic competence lower than a snake���s belly. Even if you think Labour���s policies leave much to be desired*, they clear this low hurdle.

How, then, can anyone believe otherwise?

One answer, of course, is motivated reasoning: it���s easy to believe what you want to believe.

Another is ambiguity aversion. To people accustomed to 30 years of neoliberalism, Labour looks like an uncertain prospect even if it is offering what is really only mildish social democracy ��� and people hate uncertainty.

A third answer is that Tory policies favour the 1% whereas Labour���s don���t, and these have massively disproportionate political influence. They also ��� unlike the poor ��� have an over-inflated sense of entitlement and take umbrage at Labour���s challenge to those entitlements.

But there���s a fourth thing I���d like to emphasize. It���s adaptation. Many people have adapted to Tory mismanagement but not (arguendo) to Labour mismanagement. And the old adage ��� and Steps song ��� is right: better the devil you know.

Some economic research is relevant here. Reto Odermatt and Alois Stutzer show that people adapt to even devastating events such as widowhood and disability; this confirms research by Andrew Clark. And ��� what is relevant ��� they fail to see that they will adapt. They expect that changes will hurt more than they in fact do. Psychologists call this the impact bias.

Some work by Christoph Merkle corroborates this. He surveyed UK stock market investors just before the crisis and found that they said that big losses would make them miserable. After incurring those losses, however, investors were much more content than they expected to be. We���re prone, he says, to loss aversion illusion.

All this is of course another way of saying there���s a status quo bias: we prefer current bads to prospective ones, even if the latter are milder. This is because we fail to see that we've adapted to our current situation and fail to anticipate future adaptation.

In this sense, when Labour policies are compared to Tory ones, we don't compare like with like and so judge Labour more harshly. We give the Tories an easy ride because we fail to see that we've adapted to their incompetence without anticipating we'll also adapt to Labour's. This bias is exacerbated by a tendency to attribute feared policies as well as real ones to a future Labour government; a failure to appreciate that Labour's worst policies will be abandoned or watered down; and by an under-estimation of the resilience of the economy to bad policy.

I fear, however, that this isn���t just a cognitive bias but also a media one. Listen, for example, to this (14���55��� in) hilarious exchange between posh people who know nothing. Which brings me to a point I���ve made before: the BBC is biased not so much because it���s chock full of right-wing gits, but because of more insidious subtle biases to which it is insufficiently alert.

* I���d describe them as macro good, micro bad (with the exception of McDonnell���s wholly admirable support for coops), but it takes a lot of Harberger triangles to fill an Okun gap.

September 28, 2017

Ducking questions about capitalism

Theresa May���s speech this morning was trailed as a defence of free market capitalism. If that���s what it was, it failed because she failed to answer the big questions.

May said:

A free market economy, operating under the right rules and regulations, is the greatest agent of collective human progress ever created.

This is true. The excellent economics course devised by Wendy Carlin and Sam Bowles begins from this very fact. But it is a fact upon which Marxists agree. Marx and Engels wrote that

[Capitalism] has accomplished wonders far surpassing Egyptian pyramids, Roman aqueducts, and Gothic cathedrals���The bourgeoisie, during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together.

The question is: can this continue? Marx ��� following classical economists��� forecasts of a stationary state - predicted that it wouldn���t, and that capitalist property relations would turn into ���fetters��� which constrained growth. The fact that we���ve had a decade of falling real wages and stagnant productivity is consistent with the possibility that Marx was right. Maybe a falling rate of profit, fear of competition, capitalist hierarchy and state-backed monopolies are constraining growth. If so, we might need something close to the overthrow of capitalism to restore growth.

Do we? May doesn���t even consider the question.

Nor does she ask its correlate: why exactly have wages and productivity flatlined for so long? If it���s not because of structural capitalist stagnation nor presumably because of fiscal austerity then why? And if there are policy changes that can remedy these, why have they not been implemented since 2010? Yes, Ms May speaks of progress in financial regulation. But does she seriously think this is sufficient to end financial crises ��� that we���ve finally achieved an end of history in which crises are abolished?

Yet another question is: do we really have a free market economy? In many sectors, the answer is: no. Banks and utilities are far more like rent-seeking state-aided oligopolies than the textbook perfectly competitive markets. There���s a reason why Labour wants to renationalize railways and utilities and not your local greengrocer: it���s because some are monopolistic and others aren���t. Labour���s nationalization plans are not an attack upon markets ��� at least not on well-functioning ones.

Which raises a further question: what is the relationship between capitalism and markets? Yes, historically the two have been correlated. But this is not a logical necessity. Capitalism is about who owns productive assets; markets are about how goods are allocated. Capitalism can actually undermine free markets, as bosses seek monopoly profits and as crises and stagnation undermine public support for markets.

It is theoretically possible to have markets without capitalism; see, for example, Gary Chartier and Charles Johnson���s book, Markets Not Capitalism (pdf). In fact, in my not wholly idiosyncratic notion of socialism, markets would be healthier than they are under today���s capitalism.

Which leads to another question: are the Tories really able to defend free markets any more? The problem is that, as Phil says, they are the allies of the most ���socially useless section of capital���: rentiers, low-wage bosses, tax-dodgers and a few financiers. This is not the group we should look to for an advancement of healthy markets.

I like to think that there should be a case for free markets. This requires that they operate in frameworks that constrain rent-seeking and exploitation. It���s not at all clear that the Tories can make such a case.

* To his credit, Tim Worstall has always been clear about this.

September 27, 2017

McDonnell's Marxist critics

It���s sometimes said ��� usually by those who know nothing about Marxism ��� that John McDonnell is a Marxist. In one sense, this is the exact opposite of the truth: it is not McDonnell who is the Marxist, but his critics.

To see what I mean, remember that there are several differences between Marxism and social democracy. Not least of these is the question: can capitalism provide adequate living conditions (both material and non-material) for workers? Social democrats believe it can with the right policies and institutions. Marxists say it can���t.

Now, McDonnell���s main policies are social democratic ones. Higher corporate and personal taxes, more infrastructure spending and borrowing and nationalized railways and utilities are all compatible with the continuation of capitalism. They merely tweak the mix of public and private sector activity towards the former. Anybody in western Europe, or who remembers the 1960s, should be familiar with this.

Let���s, though, assume (for the sake of argument) that McDonnell���s harshest critics are right and that these tweaks would be very damaging: that higher borrowing would raise interest rates and crowd out private sector capital spending; that higher corporate taxes would deter investment; that higher minimum wages would destroy jobs; that higher top taxes would have big adverse Laffer curve effects; and that regulations such as bans of zero hours contracts or high credit card charges would cumulatively depress economic activity.

What this amounts to is exactly the attack that Marxists make against social democrats ��� that they cannot reform capitalism to greatly help workers.

In fact, such criticisms go further than I would. True, I���m sceptical about higher corporate taxes and minimum wages, and I doubt that trend growth is as malleable as McDonnell thinks. But I resist CapX-style hyperbole because I suspect that developed economies are more resilient to bad policy than many people think. (We'd be out of luck if it were otherwise.)

Of course, these attacks on McDonnell would not be Marxist at all if they were accompanied by positive defences of capitalism. If we lived in an economy in real wages were growing and jobs improving, McDonnell���s critics could argue coherently that unreformed capitalism was delivering rising living standards and that social democrats and Marxists were both wrong.

But this is not the world we live in. Real wages are lower than they were ten years ago; productivity is growing at close to its slowest rate since the start of the industrial revolution; job prospects for diligent but non-academic people are worsening; and working conditions are bad for many and deteriorating even in once-good jobs.

Capitalism as it currently exists is failing working people. If this fact is accompanied by claims that social democratic reforms will fail, then we have the Marxian conclusion ��� that capitalism opposes the interests of working people.

Can rightists escape this bind?

Maybe. They need to show that other tweaks to capitalism would work. And I mean seriously so: fantasies about deregulation and platitudes about increasing opportunity aren���t good enough.

So, here���s my challenge to McDonnell���s rightist critics: can you really show ways of making capitalism work (again?) for working people? Or are you just going to continue to support we Marxists?

September 26, 2017

Brexit & austerity

Nick Clegg spoke for many critics of Labour���s ambiguity towards Brexit when he said:

You cannot end austerity if you don't end Brexit. Ending austerity and proceeding with Brexit are incompatible with each other.

There���s some truth in this. Brexit means slower economic growth than we���d otherwise have, which in turn means less growth in tax revenues and hence in potential public spending.

The question ��� one which is surprisingly rarely asked in all political contexts ��� is: how true is it?

To get an idea of this, let���s remember some basic fiscal maths. The primary deficit (that is, government borrowing excluding debt interest payments) required to stabilize the ratio of government debt to GDP is given by the equation:

D*[(r-g)/(1+g)]

Where D is the debt-GDP ratio, r is real interest rate and g the real annual growth rate.

Let���s put some numbers into this. Let���s say that g is 1.5%. This is 0.8 percentage points less than its rate over the last 50 years, to reflect the damage done by Brexit: the OBR assumes it to be 2%, so I���m being more cautious than them. And let���s say that 20-year index-linked gilt yields rise by a percentage point to minus 0.5% by the time Labour takes office in 2022. The OBR envisages D being 83.6% then.

Plugging these numbers into our equation tells us Labour could stabilize the debt GDP ratio with a primary deficit of 1.6% of GDP. But current plans are for a surplus of 0.9%.

Labour could therefore borrow 2.5% of GDP more each year and still stabilize borrowing, even If we assume Brexit hurts economic growth. Clegg is therefore mostly wrong. Ending austerity and proceeding with Brexit are not incompatible ��� unless you assume a very big hit indeed to growth from Brexit or a very large rise in gilt yields.

Note here that I���m using bog-standard orthodox economics: I���m not arguing here that Labour need monetize borrowing.

How, then, might we rescue Clegg���s claim?

You could argue that fiscal policy should aim at reducing the debt-GDP ratio if (as the OBR assumes) the economy is on its trend path in 2022. This, though, requires you to argue that the current ratio is too high, which I think takes some doing and is independent of the Brexit debate.

Alternatively, you might argue that much bigger borrowing would be inflationary. This, though, runs into two objections. One is that the flat Phillips curve suggests that higher aggregate demand might add less to inflation than previously thought. The other is that, to the extent that inflation does rise, it can be offset by tighter monetary policy. To argue against ending fiscal austerity thus requires you to argue for the mix of loose money and tight fiscal policy. This is a worthwhile debate, but it���s largely orthogonal to Brexit*.

In fact, from one perspective Brexit makes a Labour government more necessary. Insofar as Brexit reduces trend growth, we need policies to offset the damage. The Tories offer nothing here, whilst some of Labour���s policies do: infrastructure spending; a state investment bank, encouraging coops and so on. Granted, we should be sceptical here not so much because these are lousy policies but simply because it���s so damned hard for governments to raise long-term growth. But we should at least try, and Labour at least recognises the problem.

* FWIW, I think there���s a case for a mix of tighter money and looser fiscal policy, in part to get us away from the ZLB quicker, and in part to dampen down house prices, high levels of which are an economic menace.

September 25, 2017

Labour's understandable Brexit confusion

It���s insufficiently appreciated that political differences are due not just to different values but to differences in what people think important.

To take an obvious example, leftists are concerned about inequality whilst many free market rightists tend to be relaxed about it.

Conversely, the free market right worries about the deadweight costs of regulation whilst the left is less concerned by those and more troubled by the costs of austerity. As James Tobin said, "it takes a heap (pdf) of Harberger triangles to fill an Okun gap." By the same token, (some) Tories are troubled by high government borrowing whereas lefties ��� for now at least ��� are not.

Immigration, I suspect, is another example. Some rightists ��� and leftists of the Blue Labour tradition ��� are concerned by the cultural effects of immigration. And although some on the left positively celebrate multiculturalism and a (perhaps partial form of) diversity, many more of us are just relaxed about it: much of my writing on immigration has been motivated less by positive support for it than by a desire not to see immigrants mistakenly scapegoated for the failures of austerity and capitalism*.

Which brings me to Brexit. Until last year, I hadn���t given any thought at all to whether the UK should be a member of the EU or to what form leaving might take. I simply took membership for granted. And I suspect that in this, if not in much else, I am a typical lefty.

From this perspective, the allegation that Labour is confused about Brexit is both true and unsurprising. The party has given the subject little thought, and has no recent intellectual tradition of doing so: yes, membership was an issue in the 70s and early 80s, but it was settled for almost 30 years until the Tories raised it.

Equally, though, Labour���s conference organizers are right not to want to vote on the matter. To do so would make the party appear divided to no very good purpose. Labour���s approach to Brexit should be as far as possible to present itself as an innocent bystander. Its attitude should be: ���this is the Tories��� shit; they should shovel it.��� Brexit has for years been a low-salience issue for Labour though not for the Tories.

Which raises a puzzle. It���s no surprise that the Tories are making a mess of Universal Credit; the party has traditionally had little interest in welfare except to want to, ahem, sharpen work incentives. What is odder is that it should also be fouling up Brexit given that many in the party have for years thought about little else**. Which goes to show that there���s a surprisingly big difference between being obsessed with a subject and being knowledgeable about it.

* In fact, immigration and inequality have something in common. The best defence of them is that both are mostly harmless by-products of freedom ��� though as an empirical matter, I believe this is more true of immigration.

** There might be a parallel here with the mess the Russian communist party made of economic policy after 1917: having wanted revolution for years, the party didn���t know what to do with it. Yes, there���s nothing conservative about the Tories.

Another thing: All this raises the possibility that the BBC can be biased. If, for example, it reports (say) government borrowing more than it reports stagnant living standards and inequality, it���s reporting will be biased towards Tory issues.

September 23, 2017

The intelligent state

What���s the best way of protecting vulnerable workers? Two things I���ve seen recently poses this question.

First, Daniel Pryor notes that higher minimum wages do destroy some jobs, such as those of young unskilled ones in jobs that can be automated. And then James Bloodworth points out that banning Uber from London would cost the jobs of some drivers, many of whom are highly-indebted.

What we have in both cases are examples of how regulations have ambiguous effects. Minimum wages both raise the incomes of the low-paid and also put a few out of work. Cab regulations both protect customers from dangerous cabbies and destroy some jobs*. And in both cases, the cost is borne by the most marginal and vulnerable workers.

This is not to say such regulation is a bad idea: it���s perfectly possible that the benefits outweigh the costs. But it does pose the question is: can we do better?

Yes. The best way to help workers is to create conditions which increase their bargaining power ��� which give them the option of using Johnny Paycheck���s words: ���take this job and shove it���. Such conditions would involve a mixture of over-full employment**; a jobs guarantee; stronger trades unions; and a citizens��� basic income which allows workers to either walk away from lousy jobs or to work only a few hours.

Such bargaining power has an advantage over regulations ��� flexibility. It would allow there to be low wages or poor employment conditions where workers wanted them and where the alternative was no job at all whilst empowering workers to do better for themselves in other circumstances. It harnesses the laws of supply and demand to raise wages, and also the dispersed local knowledge of particular workers so they can distinguish between situations where high wages would destroy jobs and where they wouldn���t.

In fact, such policies and institutions have another virtue. In generating a tight labour market they would raise productivity by forcing employers to economize on labour by investing, innovating and generally upping their game. It might well be no accident that the biggest rises in productivity in history occurred during the years of post-war full employment.

What I���m calling for, then, is an intelligent state ��� one that devolves regulation to workers who know how to implement it in response to particular localized conditions***.

Which poses the question: why don���t we have such a state? One reason is that managerialist ideology overstates the knowledge that central authorities can possess and under-rates the importance of dispersed knowledge. Another reason, though, is that I���m calling for workers to be fully empowered, and a state that has been captured by capitalists is inherently hostile to such a scheme.

* TfL is not revoking Uber���s license because of its poor employment practices, but many lefties are welcoming it for that reason.

** Although unemployment is very low, the very fact that wage inflation is so low tells us we are not yet at this point.

*** Also, an intelligent state wouldn���t regulate Uber out of existence, but rather compete it out of existence by setting up apps for cabbies to use themselves in more cooperative ways, as the NEF has suggested.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers