Chris Dillow's Blog, page 51

November 15, 2017

Selecting for inadequates

���Why are Brexit���s political champions so unimpressive?��� asks Janan Ganesh. Making the same point, Simon says:

The political system fails to select for competence, understanding or respect for wisdom and knowledge.

But why do we have such underwhelming politicians?

Here, we must guard against two errors. One is the tendency to believe that people are stupid just because they disagree with us. The other is a tendency to romanticize the past: it���s not that politicians were all giants years ago, but that we have grown up.

Nevertheless, I suspect Janan and Simon have a point. Looking just at Tories (so as to avoid the former error) I am less impressed now than I was in the 80s. No top Tory has the clarity of mind and purpose that Thatcher had: Thatcher inspired hatred on the left whereas May arouses only contempt - that's a big difference. Boris Johnson���s predecessors at the Foreign Office such as Carrington, Howe and Hurd had an integrity and seriousness of purpose which he wholly lacks. And ��� I���m showing my age here ��� even Nigella���s dad once had an intellectual credibility which is absent from most senior Tories now.

This poses the question: what are the mechanisms which have selected for such mediocrities?

Politics has always been a profession where once can succeed through luck as well as merit (maybe even more than merit), and so attracts overconfident second-raters. But there might be other things at work. Here are a few theories.

- Declining Tory party membership. The Tories were once a mass party; they had over two million members in the 50s. Today, they are a handful of ���weirdos and oddballs��� who are ���apart from reality���, to use Richard Bridger���s words. This means that whereas Tory MPs were once selected for their ability to appeal to sane and reasonable folk, today one can become a Tory candidate by enthusing weirdos.

- The rise of narcissism. The only thing we expect of politicians today is that they echo our prejudices, not that they exercise good independent judgment or promote the public good; the fact that there is a demand for referendums demonstrates a distrust of our elected representatives to do their job. We thus prefer the third-rate fanatic to the serious sober-minded man. The media, of course, is complicit in this. The right-wing press bullies independent-mined MPs, whilst the BBC ��� in its pursuit of balance ��� describes outright lies as ���controversial claims���.

- The Tories' loss of contact with business. In backing Brexit and immigration controls, Tory policies are not business interests. Of course, relations between the Tories and business haven���t always been close: in 1980 CBI boss Terry Beckett threatened a ���bare-knuckle fight��� over monetarism. But the Tories then had links to corporate life which gave them roots in a reality-based community. Today, those roots are weaker.

- Increased inequality. Financial rewards in finance or business are now higher, relative to those in politics, than they were in the 70s and 80s. People of even moderate ability are, therefore, more likely to stay away from politics. Why become a cabinet minister to be harangued by a bigot earning five times as much as you, when you can earn more, with more dignity, elsewhere?

- The loss of public intellectuals. Thatcher could (and did) draw upon serious thinkers such as Popper, Hayek and Friedman. There are no equivalents of these today. The best Brexiters can manage are a bunch of cranks whose work doesn���t withstand scrutiny.

Of course, none of this is to say that intelligent public-spirited people are always weeded out: they are not. It's just that there are mechanisms which tend to select against such people. Nor is it the case that politics is unique in tending to select against honesty and merit. There are adverse selection mechanisms in many organizations. The point is, though, that we should not just decry the mediocrity of our political leaders, but ask what mechanisms give us such inadequates? And how, if at all, can these be changed?

November 14, 2017

Inequality, investment & trickle down

I���ve never been sure whether trickle-down economics was a genuine theory or a straw man which leftists attribute to the right. I was therefore surprised to see Tim Worstall write in defence of the idea that:

greater investment by the richer among us (this being the flip side of the obviously true greater marginal propensity to spend of the poor) creates a wealthier society over time.

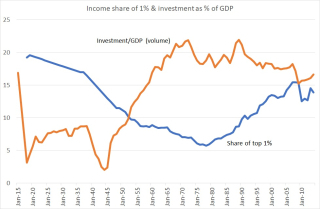

This claim, however, doesn���t seem to me to be true. If it were, we���d expect to see higher inequality leading to higher investment. But this isn���t the case. My chart shows that the share of investment in GDP rose in the 50s and 60s as inequality fell, and has fallen since the mid-80s as inequality rose.

This is the exact opposite of what we���d expect if Tim were right. It is, though, consistent with research at the IMF, which shows that inequality tends to reduce economic growth; for explanations of how this can happen, see the brilliant Sam Bowles (pdf.)

To see why might inequality reduce investment, first remember Keynes��� point that a decision to abstain from consumption does not necessarily mean a decision to invest in productive assets. The rich���s lower marginal propensity to consume might merely mean that they hoard their wealth.

This in itself is one reason for the pattern in my chart: insofar as greater equality means a higher propensity to consume, it tends to raise aggregate demand and hence strengthen the accelerator effect. We thus get more investment and wage-led growth. By the same token, inequality weakens the accelerator and so reduces investment and growth.

Alternatively, high inequality might cause the rich to fear a backlash in the form of higher taxes, political unrest or leftist governments which would deter them from investing: uncertainty alone depresses investment.

And then there���s the fact that inequality causes the rich to try to entrench their privilege by investing in guard labour rather than more productive jobs, or by using the state to protect them from competition ��� for example by enforcing tough intellectual property laws, extracting subsidies for banks and corporate welfare, or imposing regulations which restrict creative destruction. In this way, investment and growth are choked off. In saying this, I���m not making a terribly radical point. In a new book Steven Teles and Brink Lindsey, who are no raving lefties, write:

The economic game has been rigged in favour of people at the top���the US economy has become less open to competition and more clogged by insider-protecting deals than it was just a few decades ago. Those deals make our economy less dynamic and innovative (The Captured Economy, p5)

I���m not sure you can argue against all this on the grounds that inequality would raise investment and growth if all else were equal. The problem is that inequality affects pretty much everything ��� policies, institutions and the likelihood of financial crises. Very little is exogenous to inequality.

Instead, I suppose you could argue the following:

After WWII there was massive pent-up demand for investment, because the war had delayed the adoption of recent innovations. That led to rising capital spending. By the 1980s, however, that pent-up demand had disappeared, and a slower pace of innovation meant less investment. Quite by accident, these developments coincided with a decline and then rise in inequality.

I suppose this might explain the pattern in my chart. But it doesn���t explain the IMF���s finding that inequality depresses growth. Nor does it dispose of the many mechanisms whereby it might do so.

I therefore side with Richard Murphy. Trickle down is indeed discredited. Defenders of inequality must come up with something better.

November 13, 2017

Is Redwood right?

Frances Coppola points out that whilst John Redwood the politician is talking up the benefits of a hard Brexit, John Redwood the financial advisor is telling us to invest outside the UK.

There���s a danger here of Mr Redwood���s opponents seeing a conspiracy ��� that he���s talking pish about Brexit but the telling the truth in his capacity as a financial advisor. I���m not so sure. It might be that he���s wrong in the latter capacity, and that investing overseas isn���t in fact such a good idea.

I say so because Brexit isn���t the only consideration here. There���s also this paper (pdf) by Martin Eichenbaum, Benjamin K. Johannsen and Sergio Rebelo. They say:

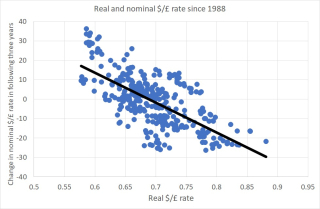

the current real exchange rate is highly negatively correlated with future changes in the nominal exchange rate at horizons greater than two years.

My chart shows this for the $/�� rate. The correlation between the real rate (the nominal rate multiplied by relative CPIs) and subsequent three-year changes in the nominal $/�� rate is minus 0.68. By the standards of exchange rates, this is enormous. For example, a high real rate in 1990, 1997, 2006 and 2014 led to sterling falling, and a low real rate in 2001 and 2009 led to it rising.

Sterling���s rise from last October���s lows is consistent with this pattern.

This is, essentially, a variation on Rudiger Dornbusch���s theory of exchange rate overshooting. Which in turn is a generalization of the idea that asset prices tend to over-react.

With sterling���s real rate now low, this relationship points to the pound rising. It���s quite possible therefore that even if foreign shares out-perform UK ones in the future ��� as they have for years ��� this out-performance will be offset by exchange rate losses. It���s not clear, therefore, that Mr Redwood is right.

What might cause sterling to rise? It could be that FX markets are already discounting a hard Brexit, so there���s not much more downside on this score; sterling���s trade-weighted index is 12% below its pre-referendum levels. And it could be that the same interest rate rises that concern Mr Redwood might help drive the pound up.

Now, I don���t say this with much confidence. For one thing, non-sterling cash is a useful hedge against the risk of either global crises or UK recessions, because sterling tends to fall in both. And despite this evidence, a bit of me cleaves to my priors that exchange rates are largely (pdf) unpredictable and that only fools try to forecast them.

My point is instead a weaker one ��� that we should not assume that, in this case, Brexiters have especial wisdom that they are withholding from the electorate.

November 9, 2017

Tories' austerity doublethink

The Tories have a problem. The political winds dictate that they retreat from fiscal austerity. But how can they do so without admitting that austerity was an error in the first place? On the Today programme this morning (2���35��� in), Nick Boles tried. And failed. Not because of any deficiency on his part, but because he was attempting the impossible.

True, he said much to applaud: that the government must drop the target of achieving a budget surplus early in the next parliament; that the top priority must be to increase productivity and wages; that the government must borrow more to invest; and that increased borrowing is compatible with having the debt-GDP ratio fall over time.

All good stuff.

Except that he tried to reconcile this with the claim that austerity worked. I don���t think the two beliefs are compatible, for three reasons.

First, Boles claimed that increasing investment was ruled out earlier because:

When you have a deficit of ten per cent you cannot possibly splurge on investment because frankly people out there are wondering whether you are ever going to pay your money back.

This rewrites history. In 2009-10 ��� when PSNB hit 9.9% of GDP ��� longer-term index-linked gilt yields were at then-record lows of under one per cent of GDP. Such low borrowing rates tell us that ���people out there��� were not worried about the government���s creditworthiness. They were much more concerned with finding a safe place for their money in the midst of the same recession that caused borrowing to increase. The government could have borrowed more then.

Secondly, Boles says:

As long as you���re spending the money on investment then there���s a very good prospect it will generate a return in the economy that will enable you to pay that debt down.

This, though, is less true now than it was a few years ago. Back then, we had a large output gap: the OBR estimates it to have been between 2 and 3 per cent in 2011-14. That meant that some extra investment spending would not have raised inflation but merely closed the output gap faster. Which in turn means that the fiscal multiplier was probably large then ��� because there���d have been no offsetting monetary tightening. As the IMF said in 2012 (p43 of this pdf):

In today���s environment of substantial economic slack, monetary policy constrained by the zero lower bound, and synchronized fiscal adjustment across numerous economies, multipliers may be well above one.

Today, though, it���s likely that multipliers are smaller. Last week Bank Governor Mark Carney said (pdf):

The pace at which the economy can grow without generating inflationary pressures has fallen relative to pre-crisis norms. This reflects persistent weakness in productivity growth since the crisis and, more recently, the more limited availability of labour.

This means that any incipient rise in aggregate demand caused by a fiscal loosening will now be more likely to lead to higher interest rates than would have been the case in 2010-14. But this means fiscal multipliers will be smaller now because fiscal policy will be partly offset by tighter monetary policy.

If it is true today that extra investment spending will pay for itself, then it must have been even more true in 2010-14. By this standard, if fiscal loosening is correct today, it would have been more correct five years ago.

Which raises a third problem: why is productivity so weak? It���s at least possible that austerity is partly to blame (not wholly, but partly). As Simon says, weak demand and weak expected demand might have deterred firms from investing and innovating. Unless you rule this out completely ��� which is difficult - you must admit that austerity was an error.

Now, I don���t say this to argue against a loosening now. Quite the opposite. I still think there���s a case for a mix of looser fiscal and tighter monetary policy, not least because it would get us away from the zero bound. I therefore welcome the sinners that repenteth. But I don���t see that the case is much stronger now than it was a few years back.

Instead, I fear that Tory efforts to defend both austerity then and looser fiscal policy now are mere doublethink ��� the product of motivated reasoning. We might, though, be seeing a lot more of it. And given our supine media, it will not be sufficiently scrutinized.

November 8, 2017

Notes on the Russian revolution

It's the 100th anniversary of the Bolsheviks taking power in Russia. Here are some of my thoughts on it:

1.The revolution did not fit Marx���s idea of what a socialist revolution should be. He thought that:

No social order is ever destroyed before all the productive forces for which it is sufficient have been developed, and new superior relations of production never replace older ones before the material conditions for their existence have matured within the framework of the old society.

This was probably not the case in Russia then. And he feared - rightly as it turned out - that a premature revolution would lead to continued struggle. As G.A Cohen wrote:

[Marx] thought that anything short of an abundance so complete that it removes all major conflicts of interests would guarantee continued social strife, "a struggle for necessities and all the old filthy business". It was because he was so uncompromisingly pessimistic about the social consequences of anything less than limitless abundance that Marx needed to be so optimistic about the possibility of that abundance. (Self-ownership, freedom and equality, (p10-11)

2. The revolution was not predictable. As Paul Berman says, it was ���a matter of chance��� predicted by no one at all.��� It���s far more an example of the role of emergence than of historical determinism. The rise and fall of communism teaches us that social orders might be more brittle than we think.

3. The idea that the Soviet Union was destined to collapse contains a massive hindsight bias. For much of the mid-20th century, communism was seen as not just a viable system but a serious challenger to capitalism.

4. Rightist attitudes to communism are hypocritical. For example:

- They follow Popper and Berlin in deriding the notion of historical determinism (perhaps rightly) but claim that it was inevitable that communism would descend into tyranny.

- They claimed (rightly) in the 70s and 80s that a big defect of Communism was its restriction of freedom of movement ��� for example banning dissidents from leaving. Yet today, many of these support for immigration controls. They cheered when Reagan told Gorbachev ���Tear down this wall���, and also when Trump proposed to build one.

- Many cold warriors attacked the USSR���s lack of freedom, whilst supporting the illiberal regimes of Apartheid and Pinochet���s Chile.

5. The revolution had ambiguous effects on the western left. On the one hand, it greatly weakened it by associating socialism with tyranny and by splitting the left not just between Communists and non-Communists but between those with different diagnoses of the USSR���s failings. On the other hand, though, the threat of communism might well have reined in western inequality by forcing capitalists to buy off discontent. It might be no accident that inequality was low during the cold war but has increased since the collapse of communism.

6. We leftists have learned the lesson from the failure of communism. Hardly any of us now believe in undemocratic top-down central planning. We envisage alternatives to capitalism as being various forms of market socialism or participatory economics. Supporters of central planning can still be found ��� but in the boardrooms of large companies. In truth, the issue here is one of transactions cost economics (pdf): to what extent are transactions better (pdf) done decentralized (by markets or other forms of cooperation) or by hierarchy? The answer, of course, is: it depends.

7. We have also learned what a revolution should not be. It���s not the violent seizing of the state by a handful of people. Instead, it requires the building of mass support, and the creation of building blocks ��� small non-capitalist behaviours and structures that can grow.

8. The Bolshevik revolution was the seizing of power through a mix of tactical skill, foreign help and a loss of authority by an incompetent regime. It led to social division and confusion as the Bolsheviks did not know what to do with their victory, and ultimately to failure. In this sense, there are perhaps parallels with Brexit.

November 7, 2017

The Wykehamist fallacy

Simon accuses Nick Robinson of under-emphasizing ���the conflict between scientific and acrobatic journalism��� ��� that journalism which seeks the truth and that which is ���always looking for balance.��� This raises the question: why would Mr Robinson (and much of the BBC) have such a blindspot.

I suspect it���s partly because of a longstanding assumption among much of the Establishment, of which the BBC is part. This assumption is a form of the Wykehamist fallacy, the belief that members of that Establishment are jolly good chaps, usually because they went to the right schools and universities.

If you believe this, you���ll believe that disagreements are between decent honest men (usually men) who happen to have a partial perspective. Given this assumption, it follows that the truth is likely to be somewhere in between. There will then be no great tension between balance and the search for truth.

We don���t have to look far for examples of the Wykehamist fallacy. We���ve seen it for example in the treatment of Boris Johnson as a loveable eccentric rather what he is, a dangerous idiot: it might be no accident that the only BBC interviewer to expose him is a lorry-driver���s son from Dundee and not the standard simpering deferential posh journo.

In truth, of course, the Wykehamist fallacy is an ancient one. Adam Smith was describing something like it when he wrote:

We frequently see the respectful attentions of the world more strongly directed towards the rich and the great, than towards the wise and the virtuous. We see frequently the vices and follies of the powerful much less despised than the poverty and weakness of the innocent. (Theory of Moral Sentiments, I.III.29)

Nor, of course, is it confined to the BBC. Janan Ganesh writes that the British political system ���trusts the life of the nation to a few offices and prays for worthy occupants.��� This is because there���s been an assumption that those occupants would indeed be jolly good chaps.

This is also why MPs day-to-day behaviour went largely unpoliced at least before the expenses affair; why the top professions were traditionally self-regulated; why there���s been little restraint upon chief executives; and why there was until quite recently little serious effort to stamp out large scale tax avoidance.

All these are the results of the Wykehamist fallacy ��� the belief that jolly good chaps can be trusted to do the decent thing.

But they can���t. MPs��� sexual harassment, legalized theft by bankers and bosses, and tax-dodging all testify to the fact that the JGCs are morally indistinguishable from the people on the Jeremy Kyle show: they just have better teeth.

Which brings me back to Simon���s point. When one side of a debate tells a bare-faced lie ��� about that ��350m for the NHS for example ��� a conflict between scientific and acrobatic journalism does arise. But you���ll not see it if your presumption is that people will at least try to tell the truth if they went to good schools, as Johnson, Farage and Banks did.

Now, I have an open mind on the question of whether the Wykehamist fallacy was always wrong or whether it���s become more so in recent years, and if so why. It does, however, seem to be the case that the BBC���s efforts to strain too hard for ���balance��� in one sense reveals that it is, in another way, profoundly unbalanced. And in a class-divided society it could not be otherwise.

November 5, 2017

How to defend capitalism

Dear right-wingers.

Capitalism as it currently exists has come into question; huge numbers of voters support nationalization of utilities and widespread price and rent controls. This poses the question: how can you defend actually-existing capitalism?

It���s often difficult to build a strong argument if you only talk among yourselves ��� as we leftists spent years discovering. Here, then, is some advice from an opponent.

First, recognise that anti-capitalism has an economic base. Capitalism hasn���t come into doubt because people woke up stupid one morning. It���s in question because it has stopped delivering the goods. Productivity has flatlined for ten years ��� something that hasn���t happened since the early days of the industrial revolution. That���s why real wages have fallen, which is why people have got the hump.

In this context, it���s not good enough to say that capitalism has raised living standards immensely. True, it has. But that stopped a decade ago. When you celebrate capitalism you look like a Nottingham Forest fan celebrating his team���s success oblivious to the fact that it was all years ago.

It���s also not good enough to claim that free market capitalism would be OK if it weren���t for cronyism. There are strong economic forces which cause markets to descend into cronyism. You should ask: what are the economic pre-conditions of a healthy market economy? They might not be ones you favour.

Second, forget morality. Yes, there is a moral case for free markets. Most people���s view of economic systems, however, is Deng Xiaoping���s: ���It doesn't matter whether a cat is white or black, as long as it catches mice." This requires changing Universal Credit. It���s based upon a belief in the morality of work ��� which ignores the fact that in-work poverty is now a big problem. It also requires you to forget the idea that capitalism is a meritocracy. As Hayek said, even well-functioning markets are not meritocratic. And we don���t have well-functioning markets but rather systems of adverse selection and an old-boy network.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, raise productivity. Sam Bowman has some reasonable ideas. Note here, though, that there are a lot of free hits. Things like tax reform, better education, infrastructure spending and encouraging freer markets are worth doing even if they don���t greatly increase productivity.

Innovation is an especial problem here. It���s plausible that free markets don���t provide sufficient incentives to innovate: I suspect one reason for secular stagnation is that firms have wised up to Nordhaus���s finding that firms capture only a ���minuscule fraction��� of the benefits of innovation. Worse still, in actually-existing markets, what little innovation we see is socially useless or worse: this is the history of financial innovation.

Fourth, end austerity. We���re not sure exactly why productivity has stagnated. I suspect it���s largely because of inherent features of capitalism such as neoliberal managerialism, the reluctance (pdf) to invest, or a legacy of the financial crisis. But it might be because fiscal austerity has depressed demand and created what Simon calls an innovations gap. Why not at least try and prove me wrong? Fiscal austerity has helped discredit capitalism generally. Bin it.

Fifth, decide which hills you want to defend. Is it freeish markets, private ownership, high CEO pay, financialization, low corporate taxes or low personal taxes? Each is to at least some extent independent of the other. Some (such as low corporate taxes) are more defensible than others (such as CEO pay).

Sixth, decide whether to use positive or negative defences. Personally, I suspect positive defences are silly: the idea that real-world markets optimize resource use is daft. Better defences would stress that there is a great deal of ruin in a nation ��� that all systems are flawed and inefficient ��� and focus upon the dangers of government failure.

These strategies would, I reckon, make things harder for leftists like me. But they pose a question: is the Tory party today actually capable of doing any of this?

November 3, 2017

Finance, technology & power

What���s special about fintech as distinct from shopping-tech or anythingelse-tech? asks Francis Diebold. I read that question as I was on the phone to my Isa provider, who told me that to contribute to my Isa, they had to post me some documents which I had to post back. How very 19th century

Which reminded me of a paper (pdf) by Thomas Philippon who points out that decades of technological progress has not reduced costs of finance to customers:

The unit cost of [financial] intermediation is about as high today as it was at the turn of the 20th century. Improvements in information technologies do not appear to have led to a significant decrease in the unit cost of intermediation.

His work has been replicated (pdf) for Europe and the UK by Guillaume Bazot.

If you look at spreads between deposit and borrowing rates, or at fund managers��� charges, it���s clear that decades of technical progress has not led to finance giving customers better value. And this is before we consider the atrocious lack of potentially useful products; various mis-selling and market-rigging scandals; terrible management; and the enormous cost of financial crises.

From a customer���s point of view, pretty much the only useful financial innovations of recent years have been the ATM and the index tracker funds. Finance seems to be a big exception to William Nordhaus's finding that producers capture only a "minuscule fraction" of the social benefits of innovation.

History, then, tells us that the answer to Francis��� question is in the negative. In finance, technical change does not benefit customers. In the day job, I���ve suggested reasons for this such as customer inertia, distrust and barriers to entry. Fintech might instead be just another way for casino capitalism to spin its roulette wheels even faster.

This raises the question posed by J.W.Mason. If finance is so lousy at doing what the just-so stories of capitalist apologists pretend, might it not serve another function instead? Might it be instead, as he says, ���the enforcement arm of the capitalist class as a whole.���

There are several ways in which the answer could be: yes.

- High debt as a result of student loans and high house prices compel people to work harder and longer. They���re a form of modern-day debt bondage. They help maintain a high and acquiescent labour supply.

- Leveraged private equity encourages firms to sweat their assets. Private equity seems to increase productivity (pdf), but this might simply mean increased work intensity.

- The shareholder-owned company is an efficient way for bosses to extract rents, but not so obviously a good way of increasing investment.

- The centrality of banks to the economy has allowed them to extract a massive ���too big to fail��� subsidy.

On top of all this, finance helps to strengthen capitalists��� power over governments. We all know that if a government can print its own money then the only constraint upon doing so is inflation, as Frances says. But as Michal Kalecki pointed out, the belief in the myth of bond market vigilantes is very useful to capitalists:

Under a laissez-faire system the level of employment depends to a great extent on the so-called state of confidence���This gives the capitalists a powerful indirect control over government policy: everything which may shake the state of confidence must be carefully avoided because it would cause an economic crisis. But once the government learns the trick of increasing employment by its own purchases, this powerful controlling device loses its effectiveness. Hence budget deficits necessary to carry out government intervention must be regarded as perilous. The social function of the doctrine of ���sound finance��� is to make the level of employment dependent on the state of confidence.

I���m tempted, therefore, to agree with J.W. Mason. The question is: how did this arise? There���s a danger of this looking like a conspiracy theory. I suspect instead that it���s an emergent process ��� the (at least partly) unintended consequence of countless decisions.

There is, though, another point here. The fact that decades of technical progress hasn���t improved the financial ���services��� industry tells us that in a capitalist economy technology alone does not determine outcomes. Instead, the potential offered by new technologies can be wasted by market failures and capitalist power. As Marx said, ���the barriers of capitalist production are not barriers of production generally,��� Techno-optimists are apt to forget this.

October 31, 2017

Is sunlight the best disinfectant?

���Sunlight is the best disinfectant.��� If this clich�� is right, we should welcome the publicity being given to allegations of MPs��� sexual harassment as a means of cleaning up politics. After all, if an MP can abuse his power in one domain*, in what other ways might he do so?

I fear, however, that things aren���t so simple.

A recent experiment (pdf) by Andreas Ostermaier and Matthias Uhl shows one problem. They got people to roll a die and report the result, being paid for high numbers. They found that some people ��� those with consequentialist rather than rule-based moral codes ��� were less dishonest if they had to report in public than in private. This suggests sunlight is the best disinfectant.

But, but, but. Their public declarations were not wholly truthful. Instead, they lied by exactly as much as they expected others to lie; they preferred to be seen as crooks than mugs.

This experiment tells us something important. Scrutiny encourages not so much ethical behaviour as conformity to norms. Which poses the problem: what if these norms are themselves unethical? As Ostermaier and Uhl say:

As public scrutiny reinforces conformity with empirical expectations, it can promote unethical as much as ethical behaviour

We don���t need to look far for external validity here. In last year���s presidential election, Democrats hoped that revelations about Trump���s bad behaviour would lose him support. In fact the opposite happened. Democrats misjudged the norms held by many voters, who saw pussy-grabbing as evidence that Trump rejected the ���political correctness��� they hated and dishonest business deals as evidence that Trump could deal well on the US���s behalf. The norms for decent honest behaviour weren't as strong as Democrats thought.

Another example comes from former Communist countries. Rigorous scrutiny of people���s political views led them not to espouse ethical views, or even their own private ones, but rather support for dictators ��� something which helped sustain oppressive regimes because everybody believed that everybody else supported them. Timur Kuran calls this preference falsification.

I fear something similar might apply in the case of ���sex pest��� MPs. Professional golf-club bigots ��� you know who they are - respond to the allegations by blaming victims, ���political correctness��� and humourless feminazis zzzzzzz. In this way, the danger is that there���ll be a backlash against feminism rather than that bad behaviour will be weeded out.

Where norms are weak, publicity doesn���t drive out bad behaviour and might even encourage it.

In fact, I have another, different, concern. Remember the MPs��� expenses affair. This contributed to na��ve cynicism ��� ���they���re all in it for themselves��� and suchlike dazzlingly original ���thoughts��� ��� and a loss of confidence in political representatives**. The upshot was a (further?) decline in the idea of politics as a rational deliberation about the public good in favour of a narcissistic pressing of one���s own views, howsoever ill-thought out.

It mightn���t be wholly fanciful to see a link between the MPs��� expenses affair and the EU referendum; the former fuelled the belief that MPs were not fit to take decisions on our behalf.

I fear that revelations about MPs��� sexual misconduct might have the same effect. Is it really an accident that the sexual harassment spreadsheet has been publicised by a sort-of-libertarian who despises the conventional political process?

I say all this in sorrow. And I do so not merely (or even mainly) to make a point about sexual harassment. My point is that the social sciences are a matter of identifying mechanisms. There are several potential mechanisms at work here. And the one that leads to MPs��� behaviour improving is, I fear, only one possible one.

* I'm assuming, arguendo, that there's some truth in allegations of genuinely oppressive behaviour rather than just "high jinks", misunderstandings and gaucheness.

** I suspect there was a massive dollop of hypocrisy over the affair. Many of the angry older white men who professed to be outraged by MPs��� expenses claims are themselves not wholly unacquainted with imaginative accounting. Perhaps the same could be said of sexual harassment allegations.

October 28, 2017

Yes, the BBC is biased

It���s not often that John Humphrys conducts a genuinely illuminating interview, but he did so this morning (1���10��� in) with Neil Kinnock and Michael Gove ��� albeit perhaps inadvertently.

The revealing thing here is the self-congratulatory matiness. Three old boys are having a laugh together, even including a rape ���gag���*. It���s like a bad golf club. This reminds us that the political class ��� some of the Labour party (thankfully less than in the recent past), the Tories and top journalists are, essentially, all on the same side.

This smugness hid the fact that there are genuine problems with the BBC���s interviewing; in fairness, Gove hinted at one when he said there as too much focus on the Westminster soap opera and too little on policy.

To see a couple of these problems, contrast that interview with Monday���s exchange between Justin Webb and Angela Rayner (1���52 in).

I counted nine interruptions in six minutes. If we compare that to the chumminess of Humphrys with Kinnock and Gove, and to Webb���s own failure to challenge Lord Lawson���s falsehoods on climate change, a picture emerges ��� that BBC presenters are deferential to insiders such as old white men but more hostile to outsiders: how dare a working class woman like Ms Rayner have the temerity to enter politics?

Yes, the BBC has admitted that Webb���s interview with Lawson breached its own guidelines. But is it really a coincidence that such an insufficiently rigorous interview should have been conducted with a posh old right-winger rather than with (say) someone working class, or black or a woman? (Note in this context the Today programme's consistent deference towards ���business leaders���.)

Secondly, note the perspective from which Webb is challenging Ms Rayner. It���s from the ���government as housekeeper��� view. To his credit, Webb didn���t sink so low as to ask ���where���s the money coming from?��� but the presumption that Labour might spend too much on education is there.

This left another set of questions unasked. We might ask Ms Rayner: How can it be fair that some young people get two or three times as much spent on their schooling as others? Why is Labour so slow to narrow that gap? (State spending per secondary school pupil is ��6300 per year, whereas day fees at Justin Webb���s old school are ��15570 pa.) Or: Given that the government can borrow at a real rate of minus 1.5% pa, any education spending with a non-negative real return has a positive NPV, so why isn���t Labour planning to spend even more? Is it failing to take up positive investment opportunities? Or could it be that its spending won���t in fact be so productive?

That such questions went unasked in favour of a perspective that is (to say the least) questionable demonstrates that the BBC does have a bias ��� a bias against radical questions. This corroborates Tom Mills��� point, that ���the BBC will aim to fairly and accurately reflect the balance of opinion amongst elites.��� Or as Cardiff University researchers put it (pdf):

The paradigm of impartiality-as-balance means that only a narrow range of views and voices are heard on the most contentious and important issues.

This, though, is not just unbalanced, but also a way of excluding and alienating outsiders ��� not just women (that rape ���gag���) but also the working class, minorities and, we might add, the economically literate.

* Right after that comment, Gove said that ���you can make a fool of yourself��� in radio interviews. He wasn���t wrong.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers