Chris Dillow's Blog, page 50

December 9, 2017

Entrepreneurs vs bureaucrats

���The interests of Arron Banks are not those of Lloyd Blankfein��� says Simon. This highlights what I suspect is an under-appreciation distinction between two types of character, albeit ones that occasionally co-exist in the same person: bureaucrats and entrepreneurs.

A bureaucrat is one who manages an existing operation; an entrepreneur creates one from scratch. And their characters are very different. The bureaucrat values rules and convention whilst the entrepreneur scorns them: an entrepreneur, by definition, does something different. And the bureaucrat hates uncertainty whilst the entrepreneur is comfortable with it. It���s no accident therefore that the businessmen who are keen on Brexit tend to be entrepreneurs - Banks, Dyson, Martin ��� whilst those who oppose it, like Blankfein, are bureaucrats.

In making this distinction, I���m echoing Joseph Schumpeter. He argued that business would become more bureaucratic and in doing so would displace the true entrepreneur:

Rationalized and specialized office work will eventually blot out personality, the calculable result, the ���vision.��� The leading man no longer has the opportunity to fling himself into the fray. He is becoming just another office worker���and one who is not always difficult to replace���The perfectly bureaucratized giant industrial unit not only ousts the small or medium-sized firm and ���expropriates��� its owners, but in the end it also ousts the entrepreneur (Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (pdf), p133-4)

This, I think, is an under-rated forecast. I suspect ��� though cannot prove ��� that one reason for secular stagnation is that the over-optimism of the entrepreneur has been displaced (to a degree) by the cautious rational calculation of the bureaucrat with the result that innovation and investment has declined*.

One upshot of this is that, despite all the talk of disruption and new technologies, the pace of creative destruction has slowed. John Haltiwanger has documented this in the US (pdf). And whilst data is less clear in the UK, the fact that job-to-job flows are smaller now than in the early 2000s suggests something similar has happened in the UK.

As creative destruction has drained from the economy, however, it has entered politics. Brexiters such as Arron Banks fancy themselves as disruptors of conventional politics. This is perhaps most apparent in Dominic Cummings, one of the very few interesting intellectuals on the right. He���s written:

The reason why Gove���s team [in the Department of Education] got much more done than ANY insider thought was possible ��� including Cameron and the Perm Sec ��� was because we bent or broke the rules���I increasingly think there is a chance that a handful of entrepreneurs could start a sort of anti-party to exploit the broken system and create something which confounds the right/centre/left broken mental model that dominates SW1.

This is the mindset of the entrepreneur, not the bureaucrat.

Which brings me to a curiosity. From the late 70s to the 00s, the established wisdom in economic policy-making was that governments must provide a stable framework in which creative destruction could be encouraged and channelled. Thatcher and Brown, in their different ways, both agreed upon this. This consensus has now been broken: and as Cummings shows, the desire to do so isn���t confined to Brexit. We used to think that politics should be a realm of stability and business of innovation. Today, it seems as if the opposite is the case: we have disruption in politics and secular stagnation in business. (The causality between the two, if any, is another matter.)

This is consistent with a point made by the brilliant Corey Robin ��� that conservatives have never really been the lovers of stability which Oakeshott claimed them to be:

Far from embracing the cause of quiet enjoyments and secure attachments, the conservative politician has consistently opted for an activism of the not-yet and the will-be (The Reactionary Mind, 2nd ed, p63)

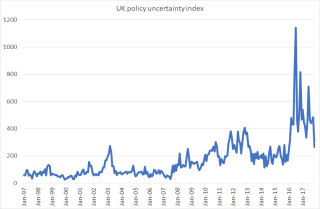

The upshot of this is that policy instability ��� as measured by Baker, Bloom and Davis ��� has been extraordinarily high recently. Economists believe this is bad for growth ��� a fact reflected in both private and official forecasts.

Most of us, I suspect, think this is a temporary aberration. But what if it���s not?

* Returns to innovation have always been low generally, as William Nordhaus has shown, which suggests it was motivated by overconfidence.

December 8, 2017

Save Democracy-Abolish Voting: A review

In an important post, Simon writes:

When politics becomes the whims and mad schemes of a small minority that only listen to themselves, unmodified by the normal checks and balances of a functioning democracy, it should be treated by the non-partisan media for what it is, not normalised as just more of the same. If we treat a plutocracy as a democracy, democracy dies.

This poses the question: what can be done about this? A brilliant new book by Paul Evans, Save Democracy ��� Abolish Voting, has some ideas.

To see the issue here, suppose you were charged with a crime you didn���t commit. You would think yourself ill-used if the jury disregarded relevant evidence or if a rich man who irrationally disliked you bought his way onto the jury or bribed them with false promises. And yet this sort of behaviour is accepted as the norm in politics. We apply much lower standards to the making of laws than we do to the application of them.

Our political system does little to ensure that voters are well-informed or careful. Paul says:

If we wanted to design a system in a way that helps wealthy and charismatic people con everyone easily, we could barely design anything better than electoral politics.

Not only does the system take little care about the information that goes into a vote, it is also careless about the information that comes from it. Take the Brexit vote. What sort of Brexit did people want? Was it a desire for Brexit at all or a protest against the ���elite��� or a call for immigration controls? If it was the latter, is this because such controls are desired for social/cultural reasons or as a (mistaken) way of increasing wages? If voters did want Brexit, was this for intrinsic reasons (national sovereignty) or as a means of achieving something else and if so what?

The referendum told us nothing about these questions. As Paul says, "the vote is such a feeble instrument of control." On such an important issue, people conveyed less information to the government than they do in the most quotidian trip to Tesco.

What we need, then, are ways both to equalize political power and to make government more sensitive to the people���s wishes. Paul���s proposal here is to give everyone a ���personal democratic budget��� which they could spend on all the possible forms of political influence - lobbyists, thinktanks, journalists and so on. People could spend this directly, or they could delegate it to syndicates of professional buyers. Political parties would then compete to appeal to these influencers.

I prefer to think of this as a thought experiment, an answer to the question: what is required to have a democracy in which people have both equal say and can convey information to their rulers? The fact that the proposals seem outlandish just shows how far we are from a well-functioning democracy.

Although this is a slim volume, it poses some deep questions which deserve far more attention than they���re getting, such as:

- Isn���t there a trade-off between liberty and democracy? Liberty requires that plutocrats can buy influence via the media, thinktanks and lobbyists. As Simon says: ���freedom is in reality just a freedom to sustain a plutocracy.��� Democracy, by contrast, requires that we all have equal political say which requires tight limits on plutocrats��� power. Paul hopes that personal democratic budgets will compete away such influence thanks to being given tax breaks. This might not be sufficient.

- How do issues get onto the agenda? The remarkable thing about Brexit is that the arcane obsession of a few rich older men has become the dominant political issue, whilst other issues (such as worker democracy) are off the table. This reminds us of what Steven Lukes said ��� that inequality of political power manifests itself in part in what becomes an issue and what doesn���t. Do Paul���s proposals do enough to ensure a more diverse agenda?

- Who actually wants democracy? Paul stresses the difference between democracy and politics: democracy entails an equal say; politics is about us getting what we want. I fear that politics has become like a football match in which everybody wants their side to win but nobody cares about the quality or honesty of the game. The constituency which wants a better democracy is a small one.

- Should politicians serve our preferences or our interests? Paul acknowledges that democracy will sometimes require acceding to irrational preferences. In a well-functioning democracy, such cases should be limited because debate should wise people up. But it won���t always do so. This poses Jason Brennan���s question: what is so valuable about democracy?

- What (if any) material economic conditions must be in place to ensure we have a well-functioning democracy in which politicians serve us all rather than the 1% (pdf)? Obviously, plutocrats will oppose any move towards equalizing political power. It might therefore be that democracy is only possible under greater economic equality than we currently have.

Even if you think Paul has the wrong solution, he is at least asking the right question. And given that so few are doing even this, he's done a massive public service.

December 7, 2017

Why Hammond's wrong

Philip Hammond is copping flak for blaming the productivity slowdown on disabled workers. He said:

It is almost certainly the case that by increasing participation in the workforce, including far higher levels of participation by marginal groups and very high levels of engagement in the workforce, for example of disabled people ��� something we should be extremely proud of ��� may have had an impact on overall productivity measurements.

The problem with this is not that it���s offensive, but that it is mostly wrong.

The ONS estimates that since 2013 the number of disabled people in work has risen by over 20%, from 2.9m to 3.5m. This means they���ve increased from 9.7% of all workers to 10.8%.

What impact might this have had upon aggregate productivity?

Let���s say ��� for the sake of argument ��� that these additional 595,000 disabled workers are only one-third as productive as average workers.

Yes, I���m picking a number out of the air here. One the one hand, this is a very low estimate: you can work as well at a desk in a wheelchair as you can if you���ve got the use of your legs. But on the other hand, it might be that the extra disabled workers are unproductive and have been cajoled into work by the threat of benefit sanctions.

I don���t think, though that the gap can be very much greater than this. For this to be the case, one or both of two things would have to be true: that the able-bodied are massively productive; and/or that the newly-employed disabled are very unproductive. The former cannot be true because wages aren���t that high (unless you want to argue they are heavily exploited which I don���t think Hammond does). And the latter cannot be, because it would imply that employers have hired tens of thousands of people whose marginal product is below the minimum wage.

Let���s, then, run with that number just to get a Fermi estimate. If we do, then it implies that the additional disabled workers have reduced productivity by 1.2% over the last four years, or 0.3 percentage points per year.

During this time, total productivity has grown 0.35% per cent per year. That compares to average growth of 1.7% per cent per year in the 40 years. So there���s a productivity growth shortfall of 1.35 percentage points, of which increased employment of the disabled accounts for 0.3 percentage points. That���s just over one-fifth.

Which of course means that fourth-fifths is due to something else. We have countless candidates here (pdf): austerity, the legacy of the financial crisis in dampening animal spirits and investment; the slowdown in world trade which has slowed the rate of increase in the international division of labour; a slower rate of innovation, or a slower rate of diffusion of those innovations due to weak competition; and so on.

All these different explanations, though, have something in common: they attribute the productivity slowdown to either bad policy or to features of capitalism.

Which brings me to what is really wrong with Hammond���s claim. First, it reveals a lack of feel for numbers: any ball-park rough estimate attributes only a small fraction of the productivity slowdown to increased employment of the disabled. And secondly, it deflects blame for that slowdown away from where it really lies and onto our weakest and most vulnerable citizens.

The first fault is hard to forgive in a chancellor. The second is hard to forgive in a human being. And Hammond is supposed to be one of the more sensible members of this government.

Update: Jonathan Portes points out that, on average, disabled people earn 10% less than the able-bodied. Even if we assume that the productivity gap is greater than the wage gap, and that the newly-employed disabled are less productive than the previously-employed ones, this suggests that my calculation errs on the side of being too kind to Mr Hammond. Which of course only reinforces my conclusion.

November 29, 2017

On moral self-licensing

There���s a piece in the Guardian on hipster racism ��� the ���domain of white, often progressive people who think they are hip to racism, which they mistakenly believe gives them permission to say and do racist things without actually being racist���.

This, I suspect, highlights an under-appreciated change in popular attitudes to ethics.

In principle, moral thinking could be a form of self-doubt: ���am I doing the right thing?���, ���What is the right thing to do?��� How can we tell?���

But it isn���t. Instead, morality serves as a form of self-licensing. Our belief in our own righteousness permits us to behave badly whilst condemning others. As Tim Farron says:

Five minutes on social media will give you a window into a society that condemns and judges, that leaps to take offence and pounces to cause it ��� liberals condemning those who don���t conform as nasty and hateful, the right condemning liberals as fragile snowflakes.

I think we see this in whites��� attitudes to racism. They attribute this to others (���the white working class���) whilst overlooking their own racism. Bosses in creative industries no doubt pride themselves on not being racist. But they don���t bother to employ black people. And don't get me started on men who claim to be feminists.

Not that moral self-licensing is confined to the left. On the right, pride in their own patriotism has self-licensed them to weaken the country by pursuing Brexit. And in the centre, Blair has justified the invasion of Iraq by saying ���I thought it was right���, thereby missing the fact that what matters is not whether you believe you are right, but whether you in fact are right.

More troublingly still, Paul Bloom describes how morality has licensed some of the very worst of crimes:

In many instances, violence is neither a cold-blooded solution to a problem nor a failure of inhibition; most of all, it doesn���t entail a blindness to moral considerations. On the contrary, morality is often a motivating force.

We have, then, a curious paradox. Everybody is certain they are morally right but very few, I suspect, are capable of rigorous ethical reasoning. Self-righteousness is all they have. How many, for example, could give a coherent answer to the question: are moral judgments questions of fact, or emotion, or what? And few seem exercised by genuine moral dilemmas: personally, I believe Brexit to be one of these.

Which poses the question: why is this?

It would be wrong to say it���s a wholly recent development. We see moral self-licensing in Howards End, where the Schlegels��� belief in their self-righteousness costs Leonard Bast a loss of wages and then his job. And Alasdair Macintyre complained back in 1981 that ���we have - very largely if not entirely ��� lost our comprehension, both theoretical and practical, of morality.��� (After Virtue, p 2)

I suspect, though, that three things have compounded the problem; these are tentative suggestions - feel free to correct them.

One is the decline of religion. Yes, religion has licensed some of the worst crimes, and still does. On the other hand, though, it also preaches humility and urges us not to judge others: ���let he who is without sin cast the first stone���. Of course, this lesson was often ignored ��� but it is more so now.

A second factor might be the rise of homogenous communities ��� especially, but not perhaps solely, on-line. When you are surrounded by people of different views, you naturally ask: am I right? Why do reasonable people disagree? When you���re with like-minded people, though, you fall into groupthink and asymmetric Bayesianism.

Thirdly, there is the decline of the public intellectual. Back in the 70s and 80s the BBC broadcast a series of interviews by Bryan Magee with leading philosophers. Such programmes today are pretty much unthinkable. What we have instead is the Moral Maze, which comprises nothing more than shouty egomaniac gobshites.

What I���m pleading for here is less self-righteousness and more self-doubt. This plea will, I am sure, be ignored.

November 28, 2017

The politics of debt fetishism

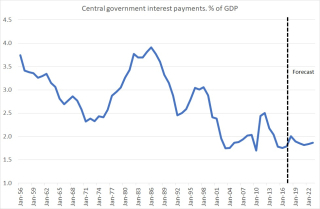

One of the sillier sights of the last few days has been the media���s pestering of John McDonnell over the costs of government borrowing: I���m not just thinking of Andrew Neil���s childish ���gotcha��� question about current debt interest payments, but also the demand that McDonnell say how much extra a Labour government would pay in interest.

Such questions are a form of statistical fetishism ��� an obsession with numbers in the abstract whilst ignoring important realities.

What matters ��� insofar as they do at all - are the public finances as a whole, rather than any single line of them. It is possible that McDonnell���s extra borrowing will boost GDP and tax revenues, as 23 economists have argued (pdf).

Frankly, their claim is questionable. The Bank of England believes ��� maybe wrongly ��� that there���s little slack in the economy. It might well therefore respond to the incipient boost to GDP given by looser fiscal policy by raising interest rates. If so, the multiplier will be small and the 23 wrong*.

This, however, is what the debate should be about: how big is the multiplier? What exactly will we get with McDonnell���s extra borrowing? Reality-based journalism would ask these questions. The BBC, though, prefers statistical fetishism.

Let���s put this another way. How often have Tory chancellors been asked: ���how much tax revenue are we losing because austerity is depressing economic activity? But this is the question that matters when thinking about the public finances.

There's something else. The fetish of debt fails to ask the question: who is suffering because of debt interest payments? The answer is: nobody, not least because they are low by historic standards.

Meanwhile, of course, real people are suffering real harm because of Universal Credit and austerity. In fact, it���s quite possible that people are dying because of the latter.

What we have here is a clash of two different types of politics ��� one that troubles itself with abstractions, versus one concerned with real lives and ground truth.

The point here, of course, is not confined to government debt. It���s a more general issue than that. Jonathan Parry complains that politics is

dominated by a ���lumpen intelligentsia���: ���earnest types who enthuse about ideas, simplify them and believe fervently that their crude and wholesale application will solve complex social problems.���

It���s this mentality which gave us Brexit.

It���s from this perspective that we see the BBC���s bias. In obsessing about debt (and about many other things such as the ups and downs of ministers��� careers) whilst under-reporting real suffering**, the BBC isn���t just making a choice between left and right. It is prioritizing the politics of fetishism and abstraction over the politics of real people. And this is anything but impartial.

* Update: Simon Wren-Lewis on Twitter corrects me here. At negative real interest rates, infrastructure spending pays for itself even if the multiplier is zero.

** The BBC���s decision not to report the BMJ paper which claimed that austerity has killed thousands ��� on the grounds that its ���conclusions were ���highly speculative��� and should be treated with ���caution��� - is of course laughable. It has not always applied such high standards.

A clarification: I���m not complaining here about right-wing bias. I would much prefer the BBC to have an intelligent and honest bias to the right than what we have now, which is a perhaps unthinking bias towards stupidity.

November 26, 2017

The rich as heroes

Here are three things I���ve read recently:

- Phil describes how opposition to a citizens��� income is based in part upon a ���cult of work��� ��� the idea that work is virtuous even if it is mind-numbing and exploitative.

- Kate says that Universal Credit is founded upon a ���contempt for people in poverty���

The (highly misleading) idea behind Universal Credit (and its strict in-and-out-of-work jobfinding conditionaility) is that people only need a kick up the backside to get out of poverty. With Universal Credit, those kicks take the form of sanctions threats, constant reminders to find more hours in jobs that already pay almost nothing, and days on meaningless, fruitless, privately-provided ���employability��� courses. In other words ��� if you���re poor, stop being poor, or else. That���s it.

- Jonn notes that some right-wingers profess to love free markets unless they hurt right-wing tabloids ��� as when a threatened consumer boycott caused Paperchase to withdraw a promotion in the Daily Mail.

There���s a common theme here. The link is a recent interview with Corey Robin in Jacobin.

Corey describes how many right-wingers regard the marketplace in the way that they used to regard politics or the battlefield - as an arena where great men reveal their heroic virtues. The successful entrepreneur is a part of an ���economic aristocracy���, a ���maker and breaker of how we do things, and transforms our world���. Although this view is associated with Ayn Rand, Corey shows that it is by no means confined to her. A paper by Olivier Fournot supports Corey���s point. He shows how bosses present themselves as Hollywood-type heroes.

From this perspective, the otherwise-odd views described by Jonn, Kate and Phil become much more understandable. There should indeed be a ���cult of work��� because work is the arena in which humans reveal their virtue and worth to others. Contempt for the poor arises because poverty is indeed a moral failing; in not making a living, people demonstrate their lack of worth. And a boycott of the Daily Mail is to be deplored because the poor should not fight back against the heroes who have been a success in the market economy.

As with any good theory, Corey���s explains a lot of things that otherwise don���t make sense, for example:

- Why there has generally been little opposition on the right to the countless ways in which the economy is rigged in favour of the rich: restrictive intellectual property laws; planning restrictions; regulatory capture; corporate welfare, bank subsidies and so on. From the point of view of free markets, these things are deplorable. Perhaps instead we should regard them as our ancestors regarded honours and grants of land to successful generals ��� as prizes for revealing heroic virtues.

- Why so many markets that could help spread risk do not in fact exist, or are relatively undeveloped: GDP futures, house price futures, insurance against social care costs and so on. The function of markets is not to allocate risk and resources, but to enable ���great men��� to make money and so reveal their heroism. This is why so much financial innovation has been downright dangerous rather than of the useful form Robert Shiller proposed.

- Why we defer to successful businessmen. It���s because they have revealed leadership skills and virtues. Whether these skills are transferable, or whether business success was just dumb luck is not important. We ask of business leaders what Napoleon asked of generals: I would rather have a general who was lucky than one who was good. It���s not just the hard right that does this. Gordon Brown forever praised ���courageous��� business leaders, and just listen to how the Today programme tends to fawn over them.

- Why so many on the right are relaxed about inequality even though it often arises from market failure. It���s because success even in a rigged market is to be applauded. The general who wins a battle is seen as a hero even if the battle wasn���t fought on a level field. Why should things be different in other domains in which heroism is revealed.

In these ways, I find Corey���s theory illuminating. Maybe we economists have missed an important fact about markets. They are not just technical means for allocating resources. They are also freighted with moral meanings - though of course we cannot agree what these are.

November 23, 2017

Notes on productivity

As had been trailed, the OBR cut its forecasts for productivity growth and hence GDP growth yesterday. Here are some miscellaneous thoughts on this.

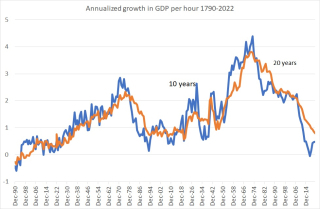

1. If the OBR is right, this means the 20 years to 2022 will see the worst productivity growth since 1891-1911, and close to the slowest growth since the early 1800s.

2. The OBR might not be right. It says there���s ���huge uncertainty��� about its forecasts. One reason for this is that we don���t really have a terribly robust theory for forecasting such growth. The OBR���s past forecasts were too optimistic because it essentially assumed growth would return to trend. We know that was wrong. But we don���t really have much better ideas.

3. The ONS estimates that productivity grew 0.9% in Q3. That���s inconsistent with the OBR���s forecast of zero growth this year ��� but it is little more than a straw in the wind.

4. Weak productivity growth isn���t wholly a bad thing, as it keeps people in jobs. As Amit Kara and Ana Rincon-Aznar point out, there has been a negative relationship between employment and productivity. Granted, this trade-off might be the result of bad macroeconomic policy. But bad macro policy is what we���ve got.

5. There���s a significant difference between the UK and US. In the US the main reason for flat real wages has been that monopoly power has risen and the labour share has fallen. In the UK, the labour share has been reasonably stable recently; the main reason for weak real wages is weak productivity.

6. History tells us that productivity growth has really only been much above 2% during the post-war era. This poses the question: to what extent was that growth due to us catching up on innovations which had been delayed by the war, and to what extent to the possibility that neoliberalism in fact retards productivity growth? A lot hinges upon this question of economic history.

7. If productivity and income growth remains weak, future governments will have to look elsewhere for revenues. The possibility of taxes on wealth (as advocated by Roger Farmer) or land thus loom larger.

8. Robert Colville ��� who���s more sympathetic to Hammond than I ��� says there ���was little sign of a serious assault��� on the productivity problem in the Budget. He���s right. For example, the National Productivity Investment Fund won���t launch until 2022.

9. We don���t really know the precise causes of the productivity slowdown. There are many contenders. I���m not sure, though, that we need to know for policy purposes. I���d advocate a broad spectrum approach of many measures such as: policies to encourage investment and innovation, which might range from tax reform to a state investment bank; more infrastructure spending; better education and training; greater worker democracy; an attack upon rent-seeking and measures to raise entry (pdf) and exit in product markets. Most of these policies are worth doing even if their impact on productivity is slight.

10. Duncan Weldon tweeted:

I suppose a small open economy slashing its growth forecasts even as global growth picks up at least shows that policymakers aren���t powerless in this globalised world.

But maybe their power is asymmetric. Governments with trend growth rates might be like monkeys with computers: they can���t improve them, but they can wreck them.

November 21, 2017

Technical change and house prices

There���s much talk that Philip Hammond will use tomorrow���s Budget to address the problem of high housing costs.

I have little doubt that high housing costs are, on balance, a blight upon the economy. What���s less clear to me, though, is whether increased housebuilding alone is sufficient to greatly reduce them. I don���t think it is. Jonathan Eley and Ian Mulheirn agree with me, whilst Jonn Elledge and James Gleeson disagree.

So, what would cut house prices, especially in expensive areas?

Teleportation, that���s what. If we could beam ourselves from one place to another Star Trek-stylee, nobody would need to pay a fortune in rents in high-cost areas such as London or Cambridge. They could buy somewhere cheap and simply teleport to London for work or nights out. Houses in (say) Burnley would become close substitutes for ones in Brixton. Prices of the latter would thus slump. Problem solved.

Pedants will object that teleportation won���t be developed anytime soon.

True. But my point isn���t wholly fictitious. There���s a precedent. A team of German researchers estimate that house prices in south east England fell by a third between 1899 and 1938 ��� a path roughly matched in several other developed countries. In the 30s, impecunious writers and artists lived in areas of London that only oligarchs and hedge fundies can afford today.

A big reason for this fall was an improvement in public transport. The opening up of the Metropolitan line, for example, allowed houses to be built miles out of London. These became substitutes for central London homes, with the result that prices of the latter fell.

You could read this as a story of increased supply forcing down prices. But it���s also a story of how technical progress reduced prices. The availability of suburban housing meant workers no longer needed to live in central London, so prices there fell.

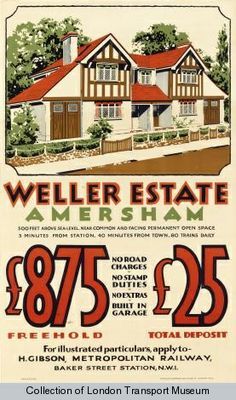

This poses the question: what chance is there of a repeat of this? I suppose it���s possible that HS2 might make Birmingham more feasible for commuters as the Metropolitan line made Amersham. A more obvious possibility, of course, is the internet. This allows me to ��� in effect ��� teleport my labours into London from Rutland. If enough people were like me, London property prices would have fallen as we sold up to telecommute.

But this hasn���t happened even years after it has been feasible.

Of course, it isn���t technically possible for everyone; baristas and chambermaids can���t work from home. I suspect, though, that there are other barriers to doing so, among them:

- Agglomeration benefits. People need to live in London to benefit from knowledge spillovers. Personally, I���m conflicted here. I know the data is consistent with Londoners benefiting from such effects. But my experience of London is that the idea of cities as serendipity engines in which great ideas emerge from chance meetings in cafes is just bollocks.

- Social capital. Young workers in particular need to build contacts so they learn of better job matches. They do this by physical proximity to others.

- Uncertainty. Living near where there are lots of potential job opportunities gives you flexibility, which is necessary if your job is at risk. I on the other hand am tied to my job.

- Domination. Even if working from home is technically feasible, bosses might block it because they want direct oversight of their underlings. As Stephen Marglin famously pointed out (pdf), capitalist hierarchies can emerge and persist because they benefit bosses rather than because of their technical superiority.

- Time lags. Erik Brynjolfsson points out (pdf) that it can take decades for technical changes to affect working practices. For example although electric power was available in the 1890s most US factories did not make best use of it until the 1920s. This was because it only raised productivity once bosses learned that motors on every machine allowed them to re-organize production. Maybe we���re living through a time lag now, and telecommuting will eventually become more common. As it does so, London���s house prices should fall.

This, of course, is not really a story about house prices. It���s a story about technology. On the one hand, this has unintended effects: the builders of the Metropolitan didn���t intend to cut house prices. On the other hand, though, it���s effects upon the economy are constrained by social, institutional and cultural factors. Technology alone doesn���t determine our future.

November 20, 2017

On the Brexit "divorce bill"

Robert Halfon says voters will ���go bananas��� if the government pays the EU a ��40bn ���divorce bill���. There might be a simple solution here.

Mr Halfon is right to think it unacceptable to fund the (say) ��40bn payment by raising taxes or cutting spending. It is vanishingly unlikely that a fiscal tightening of 2% of GDP will be justified in the next couple of years.

Nor is it right that the bill be paid by borrowing, even though the government can borrow at negative real interest rates. Borrowing is deferred taxation. Even if we set aside considerations of Ricardian equivalence, as perhaps we should, it���s unacceptable that young people today will face higher taxes in future to pay for a decision taken by their elders. And it would be astoundingly hypocritical of a government that has justified austerity on the grounds that public debt imposes a burden on future generations to demand that they do so.

But there is, of course, a trivially simple alternative here. Quite simply, the bill could be paid by printing money. The Bank of England can print ��40bn and hand it over to the government; in effect, we���d have another ��40bn of quantitative easing.

This would not be inflationary, except to the extent that converting ��40bn into euros would tend to weaken sterling: this would be a neat test of just how liquid the FX market is. This is because the ��40bn is not being spent on domestic goods and services, and so will not raise aggregate demand. If you want to see this in MV=PT terms, the increase in M will be offset by a fall in V ��� so there���s no inflation.

There���s no reason therefore to get het up about handing over ��40bn. Because we can print our own money, giving ��40bn to the EU does not mean we have to sacrifice real resources. The analogy with a divorce bill is misleading. When a man pays to divorce his wife, he suffers a loss of real wealth ��� some of record collection and DVDs and so on. This need not be the case with leaving the EU.

Of course, I believe Brexit will make us genuinely poorer. But this is because we���ll have less favourable trading terms with the EU and tougher immigration restrictions. The ���divorce bill��� is (barring the impact on sterling) neither here nor there.

Which poses the question: why are the Tories making such a big issue of it?

Simple. It���s because creating ��40bn in this way would raise the question: if the government can easily find ��40bn for the EU, why couldn���t it find ��40bn for the NHS?

In principle, there is a good reason. Spending an extra ��40bn in the domestic economy could be inflationary, whereas giving it to the EU is not. The constraint upon government spending is inflation.

The Tories, however, cannot use this argument. For years, they have claimed that austerity was necessary because the constraint upon spending was the state of public finances. That was false. If they were to pay off the EU in a rational way, they therefore have to admit that austerity was largely unnecessary.

In this sense, the Tories��� past stupidity compels them into making even more mistakes.

November 16, 2017

The politics of death

Austerity kills. That���s the message of new research in the BMJ:

Spending constraints between 2010 and 2014 were associated with an estimated 45���368 (95% CI 34���530 to 56 206) higher than expected number of deaths compared with pre-2010 trends���. Projections to 2020 based on 2009-2014 trend was cumulatively linked to an estimated 152���141 (95% CI 134���597 and 169 685) additional deaths.

This is consistent with a point made recently by Danny Dorling:

For the first time in well over a century the health of people in England and Wales as measured by the most basic feature ��� life ��� has stopped improving���The most plausible explanation would blame the politics of austerity, which has had an excessive impact on the poor and the elderly; the withdrawal of care support to half a million elderly people that had taken place by 2013; the effect of a million fewer social care visits being carried out every year; the cuts to NHS budgets and its reorganisation as a result of the 2012 Health and Social Care Act; increased rates of bankruptcy and general decline in the quality of care homes; the rise in fuel poverty among the old; cuts to or removal of disability benefits. The stalling of life expectancy was the result of political choice.

It's also consistent with international evidence gathered by David Stuckler and Sanjay Basu; with Sarah O���Connor���s report of a ���quietly unfolding health crisis��� in deprived seaside towns such as Blackpool, and with the fact that benefit sanctions have driven people to suicide.

It���s obvious what the left���s reaction to this should be. But what about the right and centre���s?

There is an intelligent response. You could argue that all this is only part of the story. Christopher Ruhm, for example, has shown that austerity can improve health in other ways. If we���re not building houses, for example, fewer men die in accidents on building sites. Hard-up people can���t afford to smoke or drink themselves to death. And if we���re under-employed we���re less likely to suffer stress-related illnesses.

Alternatively, you could invoke the trolley problem. Maybe deaths from austerity are the lesser of two evils. If the alternative to austerity is higher taxes or higher debt, it could lead to lower future growth and hence less heath spending and more death in the long run. (I don���t believe this, but some Tories sincerely do).

Neither response, though, is what we get. Instead, when Aditya Chakrabortty said on Question Time last week that the government is ���send[ing] disabled people to their deaths��� the reaction was as if he���d spat in the church���s collection plate (9 mins in).

Which in a sense he had. Aditya had the bad manners to point out that politics is a matter of life and death - at least for the poor - thereby puncturing his audience���s illusion that it is just a cosy little debating game in which the only costs are that a few MPs move down the career ladder. I had hoped that the Grenfell disaster would destroy this illusion, but it seems the imbecilities of posh folk don���t die as quickly as do the poor.

Here, though, is the thing. The supposedly impartial BBC is complicit in this. Its politics coverage too often carries a matey undertone broken only when confronted by someone who has the temerity to challenge the privilege of the rich or to enter politics without being posh. And it gives disproportionate weight to inconsequential tittle-tattle. Priti Patel���s flight from Uganda last week was given the sort of coverage due to Churchill���s return from Yalta. I very much doubt if the BMJ���s report will get so much attention.

What we have here are two competing conceptions of politics: one which sees it as a serious matter of life and death, the other as a game among careerists. The BBC is not impartial between these, and therefore not impartial at all.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers