Chris Dillow's Blog, page 47

February 14, 2018

Oxfam, & organizational drift

In the crisis at Oxfam, I fear some general points are being under-appreciated.

One is that motives are sometimes over-rated. It is the case that some of Oxfam���s critics are animated by a hostility to its campaign against inequality and by an antipathy to foreign aid. And it���s also true that, as Simon says, they are more censorious of Oxfam���s failings than of the underfunding of the NHS which is perhaps even more damaging.

But facts are facts, whoever utters them. We cannot avoid nasty truths simply because we don���t like who says them.

Sometimes bad people do good things, such as alert us to the facts.

And of course, the converse is also true. As Oxfam has shown, good people can do bad things. There are at least two mechanisms at work here.

One is ego-depletion. Working in the most Godforsaken parts of the world is hugely stressful and requires great self-control to carry on the job. Self-control, however, is limited: if we use it all up in one place, we lack it elsewhere. ���Work hard, play hard��� and the need to ���let off steam��� are clich��s because they are true. Some of Oxfam���s workers are extreme manifestations of this.

Another is moral self-licensing. If you can convince yourself you���re a good person ��� perhaps even by being a good person - you give yourself a licence (pdf) to behave badly.

On top of these, there might be a selection effect. Aid work doesn���t just attract those with a desire to do good, but those who get off on blood, gore and drama.

There���s something else, though. Organizations (or parts thereof) can and do drift away from their original purposes, because the interests or passions of incumbents can over-ride them. This was the gist of Martin Luther���s opposition to the Catholic church. It was expressed in Dostoyevsky���s Brothers Karamazov, where Jesus Christ returns to the world to be greeted by the Grand Inquisitor: ���Why shouldst Thou now return, to impede us in our work?��� Niskanen���s model of bureaucracy, the iron law of oligarchy and Alex���s description of how Capita was in effect run by its salesforce are all different manifestations of this.

All this has a troubling implication. It suggests there might be nothing unique about Oxfam, but perhaps that there are general mechanisms at work here rather than a few bad eggs. And it suggests that organizations need very strong measures in place to check these mechanisms.

February 13, 2018

Neoliberalism as lack of self-restraint

Which do people choose ��� more money or less? If you think the answer���s obvious, you���ve been too influenced by economism and not enough by science. Sigve Tjotta shows that, in a variety of experiments, a significant minority of people choose the smaller sum over the larger.

This would not have surprised the Adam Smith who wrote the Theory of Moral Sentiments. ���To restrain our selfish, and to indulge our benevolent affections, constitutes the perfection of human nature��� he wrote (TMS I.I.44). Our sense of propriety, or our desire to look good to others, he thought, reined in greed:

Though it may be true���that every individual, in his own breast, naturally prefers himself to all mankind, yet he dares not look mankind in the face, and avow that he acts according to this principle. He feels that in this preference they can never go along with him, and that how natural soever it may be to him, it must always appear excessive and extravagant to them���In the race for wealth, and honours, and preferments, he may run as hard as he can, and strain every nerve and every muscle, in order to outstrip all his competitors. But if he should justle, or throw down any of them, the indulgence of the spectators is entirely at an end. It is a violation of fair play, which they cannot admit of. (TMS II.II.11)

Which brings me to a theory. One feature of neoliberalism is that restraint in the pursuit of self-interest is now absent. Bosses lack Smith���s ���impartial spectator��� which tells them to hold back, and instead feel no compunction about jostling others. They are content to plunder customers, pensioners, sub-contractors, workers or future workers.

Among her many claims for expenses, Glynis Breakwell, Vice-Chancellor of Bath University, claimed ��2 for biscuits. Many of us would not have done so, thinking it too petty-minded to bother. Neoliberals, however, not only are petty-minded but don���t mind being seen as such by others.

In this context, critics of mainstream economics have a point. Economics��� language of optimization serves to normalize the maximal pursuit of money. What it misses is the potential trade-off which Smith identified, between greed and the good opinion of others. Randian talk of the rich as heroes also plays an important role here, as it functions to counter-act the stigma which greed would otherwise attract.

From this perspective, neoliberal bosses have something in common with child molesters. Both lack restraint in the pursuit of their own self-gratification in situations where they think they can get away with it.

And there���s the rub: where they think they can get away with it. My story here is not just about morality. Perhaps there never was a golden era of benevolent paternalistic bosses. What���s happened since around the 1970s is that the restraints upon bosses ��� from law, social norms and trades unions ��� have diminished. The problem isn���t just greed, but power.

February 12, 2018

In defence of short-termism

Rick says that UK companies are too short-termist, and that Carillion ��� which paid big dividends until soon before collapsing - is a manifestation of this. I���m not so sure.

Of course, some firms, like Carillion, have short-termist bosses and subsequently collapse. But is the collapse because of the short-termism? Or might it be instead that short-termism is a response to the prospect of collapse, and that rational managers, sensing their business is destined to fail, take money out of it?

And very many businesses do fail. The ONS shows that around 10% of firms cease trading each year, and less than half of them survive five years. Granted, failure rates are much smaller for larger or older firms. But in the long-term they are still considerable. For example, only three of the UK���s largest employers in 1907 are independent stock market-listed firms today. And a list (pdf) of the original constituents of the FTSE 100 when it was formed in 1984 contains plenty of firms that subsequently declined. A failure rate of only 3% a year means that firms have a less than 50-50 chance of making it to their 25th birthday.

If you���re not going to survive into the long-term, why not be short-termist?

And in a healthy dynamic economy, we should see lots of failures as competition and creative destruction eliminate profits. It���s only monopolies or near-monopolies that can fight off competition for many years and afford to be long-termist. Do we really want that?*

What���s more, creative destructive means there���s uncertainty even for firms that do (with hindsight) survive. This uncertainty compounds over time. On a two or three year horizon, most decent firms have a reasonable idea of where the threats from rivals or new technology come from. On a two or three decade view, however, they have no clue. Faced with that uncertainty, why not focus upon managing the company well in the short-run?

In this context, long-termism isn���t necessarily a virtue. It might instead reflect merely irrational overconfidence. Yes, short-termism might well be one cause of low capital spending. But high investment doesn���t guarantee success. As Charles Lee and Salman Arif show, it often leads instead to lower profits. This is consistent with high investment being a sign not of rational long-termism but of irrational over-optimism.

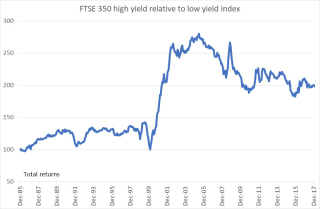

We have some more empirical evidence here. Let���s say that stock markets were too short-termist. In such a world, we���d expect them to under-price growth stocks and pay too much for stocks that pay high dividends. Generally speaking, though, the opposite has been the case. For most of the last 30 years, high-yielding shares in the FTSE 350 have out-performed lower-yielding ones: the main exception came between 2003 (when tech stocks were under-priced) and 2010**. And the FTSE Aim index ��� which contains many ���growth��� stocks��� has horribly under-performed the All-share index since its inception in the mid-90s. This tells us that stock markets have generally paid too much for growth and too little for dividends. They have been too long-termist, not too short-termist.

Of course, managers can be as irrational as the rest of us. But it���s possible to be too long-termist as well as too short-termist.

The biggest problem with corporate governance ��� as highlighted by Carillion - is not that bosses are too short-termist, but that they have too much power to plunder firms for their own private gain.

* There���s a big difference here between the UK and US: the rise of monopoly power is more pronounced in the US than UK.

** In fact, given the big decline in long-term interest rates we should have seen growth stocks boom in the 00s as investors discounted future cashflows less heavily. That this didn���t happen is yet more evidence that growth stocks have been over-priced.

February 9, 2018

Technology, power & ideology

One of Marx���s many great insights was the theory of commodity fetishism ��� the idea that in capitalism relations between people assume ���the fantastic form of a relation between things.��� For example, the labour market ��� ���a very Eden of the innate rights of man��� ��� serves to depersonalize the relation between boss and worker and disguise the fact that the former exploits the latter.

Some things I���ve seen recently remind me that this phenomenon is still very much with us.

Alex says:

So many problems that are spoken of as ���computer systems��� problems are systems problems, that just happen to be implemented using computers rather than paper or giant rocks or whatever.

In this way, management tries to pass off blame for failure onto inanimate things. He���s surely right. We���ve all heard somebody say ���our systems are down��� as if this were an act of God rather than what it is ��� bad management.

A lot of talk of this week���s stock market fall fits this pattern. We���re told that the drop was amplified by algorithmic trading, and invited to believe that if only humans were in charge the market would be more stable. This is, of course, pish: who wrote and implemented those algorithms?

Sarah O���Connor describes how a similar thing is happening in workplaces, as workers are increasingly monitored not by humans but by algorithms, with the result that ���human managers [are] hiding behind the veneer of ���data science��� to offload responsibility for their decisions.���

Technology, then, serves an ideological function. It permits bosses to shift their own responsibility onto impersonal things, and to disguise their own power by attributing it to machines. Commodity fetishism lives.

This is on top of the fact that it also provides means for capitalists to better exploit labour. Peter Skott and Frederick Guy show how technologies (pdf) such as CCTV, containerization and bar codes have allowed bosses to screw down wages; the algorithmic management discussed by Sarah is an extension of this.

There is, of course, nothing new here. Supporters of worker oppression in the 19th century claimed that workers needed to be closely supervised because it would be too expensive for thousands of pounds worth of machinery to lie idle even for a short while. James Carey describes (pdf) how the telegraph ���turned colonialism into imperialism: a system in which the centre of an empire could dictate rather than merely respond to the margin.��� And more recently, containerization facilitated globalization and hence the entry (pdf) into the global workforce of millions of low-paid workers.

But might there be a backlash here? Rene Chun describes how self-checkouts encourage shoplifting because people feel anonymous. Partial gift exchange ��� which is the foundation of many economic transactions ��� is something that happens between humans, not between people and a machine.

My point here should be an old and trivial one, but I fear is under-appreciated. It���s that technology is not merely a neutral set of possibilities for improving the human condition. It plays a central role in shaping both the reality of class relations and our perceptions of those relations ��� often in ways which we cannot foresee at the time.

February 7, 2018

Brexiters' blind-spot

Tony Yates and Andrew Neil were debating gravity models on Twitter this morning. Tony was right. The gravity model isn���t some hi-falutin theory without much factual backing. It is in fact (pdf) ���one of the most empirically successful in economics���.

Even so, talk of ���models��� is a bit fancy. Let���s instead look at some facts. According to the World Bank Germany exported $118.6bn of goods to the US in 2016. That���s $1434 per person. The UK exported $61.6bn, which is $939 per person. That's one-third less. Germany exported $85.4bn to China, or $1032 per person, whereas the UK exported only $18.1bn or ��277. To Russia, Germany exported 5.4 times as much per person as the UK. To Japan it exported 2.5 times as much, and to India twice as much. Even to Canada Germany exported one-third more per person.

These facts tell us something important. They tell us that membership of the single market/customs union is NOT a great obstacle to trade with other nations. It is not the lack of good trade deals with China, the US, or Japan that is restraining exports. Germany has exactly the same deals with them as us and is exporting far more.

What is stopping us exporting? There are countless possibilities: poor management; lack of animal spirits; insufficiently skilled workers; lack of investment; financing constraints; exchange rate volatility; a lack of price competitiveness; and so on. Many of these are, unsurprisingly, the same factors that lie behind our poor productivity.

And these will be the same after Brexit as before. They will continue to hold back exports even if we do sign free trade agreements with non-EU nations. Monique Ebell (pdf) and Silvia Nenci have shown that such deals do little to boost trade. Even if you cut legal barriers to trade, real ones remain. I am free to do a park run on Saturday, but I���ll not ��� and certainly not in a good time.

Why do Brexiters find it so hard to grasp this?

In part, it���s because some of them do ���violence to basic facts of economic life.���

But I suspect two other things are going on. One is that many support Brexit for non-economic reasons and ��� motivated reasoning being so powerful ��� they then invent reasons why it will be a good economic thing, like a man putting lipstick on a monkey and pretending it���s Rachel Riley. They forget that there are trade-offs ��� not least between sovereignty and the regulatory harmony that facilitates trade.

Also, support for Brexit is a way of avoiding unpleasant realities.

Since the 80s, the right has got pretty much want it wanted: weaker unions, more power for bosses, lower top taxes, less regulation and so on. And yet the UK���s macroeconomic performance has remained unimpressive, not least because many structural weaknesses in British capitalism remain ��� weaknesses that contribute to our lack of exports.

Brexit allows the right to avoid having to acknowledge these weaknesses, however, because they can pretend instead that we can become a great trading nation if only we are free from the shackles of the EU. This prolongs the right���s longstanding belief that British capitalism is fundamentally dynamic if only the right legal framework can be imposed. This, however, is a fantasy.

February 6, 2018

Emergence in stock markets

Stock markets are not people.

I say this because yesterday���s big fall in European stocks makes many believe that markets look more like casino than textbook efficient markets. Jonathan Portes is right to point out that, technically, this is a mistake. But it is a very understandable one. A man who cuts his valuation of an asset by over 5% on the basis of almost no worthwhile information doesn���t look terribly rational.

We can avoid this mistake by recognising that the stock market is not like a person. Share prices are not an individual���s valuation of companies��� future prospects. They are instead the emergent, unintended outcome of countless individuals��� behaviour.

This point was grasped by Keynes. Actual stock market investing, he said, is a ���battle of wits to anticipate the basis of conventional valuation a few months hence���:

The actual, private object of the most skilled investment to-day is ���to beat the gun���, as the Americans so well express it, to outwit the crowd, and to pass the bad, or depreciating, half-crown to the other fellow.

It is, he said, like those newspaper competitions, popular in the 30s, in which people have to guess which faces others will find prettiest:

Each competitor has to pick, not those faces which he himself finds prettiest, but those which he thinks likeliest to catch the fancy of the other competitors, all of whom are looking at the problem from the same point of view. It is not a case of choosing those which, to the best of one���s judgment, are really the prettiest, nor even those which average opinion genuinely thinks the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be. And there are some, I believe, who practise the fourth, fifth and higher degrees.

Investing is like a co-ordination game in which the successful trader is the one who anticipates which co-ordination equilibrium others will alight upon. The man who worries when others don���t will lose money; he may be right eventually, but this is little comfort if he���s on the dole.

What���s happened is that the focal point of this game has changed. Before Friday, the focal point was a belief that the US economy will grow nicely this year ��� or a belief that others would believe that others would believe that. Today, the focal point is the possibility that inflation will rise ��� or the fear that others will believe that others will believe���.

Even small changes in the probabilities you attach to future focal points can cause big price changes.

Let���s take a simple example. Imagine someone thinks there���s a 90% chance the FTSE 100 will be at 8000 by year-end and 10% chance it���ll be 6000. Then he���ll think the FTSE should be at 7800: (0.9 x 8000) + (0.1 x 6000). If he then revises his probabilities of these scenarios to 80% and 20%, he���ll revise his valuation down by 200 points.

You can see how this can generate volatility.

But only if people agree upon such changes. If everybody agrees a share is over-valued, it���ll have to fall a lot in price before someone changes their mind and buys. If on the other hand I think a share is cheap and you think it expensive I���ll buy and you���ll sell without the price moving. The VIX index is often called a ���fear gauge��� but it should perhaps instead be called a disagreement gauge.

Volatility will vary as the extent of agreement varies ��� one cause of which will be expected shifts in focal points. Personally, I���m not sure such shifts are foreseeable. I suspect forecasts of volatility are a bit like forecasts of GDP growth: they aren���t too bad normally (pdf), but fail when they are most needed. Which is why I have little sympathy for those who���ve lost on XIV.

And here���s the thing. Aggregate market moves tell us nothing about the rationality or not of individual participants. It���s possible for rational individuals to generate market moves that would look irrational if they were due to a single person���s behaviour: this is the message of models of rational (pdf) herding or chasing noise. Conversely, stupid individuals might generate apparently efficient markets. It���s possible that either or neither of these will be true in different times and places.

Granted, there might be some longer-term predictability of prices (based on, say, consumption-wealth ratios (pdf) or dividend yields), but perhaps there isn���t in the short-term. Stock markets are more complex things than glib soundbites from empty suits would have us believe.

February 3, 2018

Brexiter feminists

There���s a nice but under-appreciated irony about the ending of grid girls and walk-on girls at the darts; those who support the move are thinking like Brexiters.

They are following a longish tradition of posh people wanting to destroy others jobs. I���m not thinking here only of feminists who want to end porn and prostitution. I���m thinking also of Sam Brittan who wanted an end to the arms trade and Thatcherites who wanted to close the coal mines.

In all these cases there was a belief that the jobs lost will be matched by new ones created elsewhere. Sam Brittan, for example, claimed that the dislocation caused by a loss of jobs in the arms trade would be ���minuscule���, and Patrick Minford argued that miners who lost jobs would find new ones. On ITV���s This Morning, Sally Howard echoed these patriarchs when she said ���there are other modelling routes��� for walk-on girls*.

Sadly, however, this is by no means assured. We know that displaced miners did not, mostly, find good new jobs. I suspect the same might be true for walk-on and grid girls. If attractive women lose opportunities to use their ���erotic capital��� (pdf), they���ll not easily find as good jobs elsewhere. Rewarding work is scarce even for those with good qualifications, let alone those without. There���s a reason why attractive women disproportionately work in promotions, PR, TV or acting; good work elsewhere is hard to get.

What���s all this got to do with Brexit?

Plenty. (Some) Brexiters think jobs lost to the UK leaving the single market will be replaced by people exporting jam to New Zealand: Patrick Minford has at least been perfectly consistent in supporting both pit closures and Brexit. They are over-estimating labour market flexibility and under-estimating the difficulty people have in switching jobs. Likewise, those wanting walk-on girls to lose their jobs are, at best, being careless about the girls��� other options.

In fact, there���s another parallel. Both Brexiters and the banners want to impose a material loss upon some people in exchange for something immaterial ��� national sovereignty in the one case and a conception of modernity and what���s not generally demeaning to women on the other. And in both cases the losses are borne by working class people so that posh people can feel better.

* In these other jobs, of course, models are never harassed, oppressed or demeaned. Not at all, never.

A clarification: I���m not saying this to oppose feminism generally. I wholly support policies to empower women such as better education and training, and end to socialization into submissive roles, a high citizens��� income and full employment. I���d like women to be given as much real freedom as possible, and if they then choose to become walk-on girls or not we should respect their free choice.

February 2, 2018

Economists in public

There was a debate on Twitter this morning about how economists can better engage with the public.

Our efforts to do so have not been wholly futile. Granted, economists��� influence on the debate about Brexit and austerity hasn���t been as great as we would like. But on the other hand, Tim Harford and Steve Levitt have gotten a wide public audience ��� one perhaps more deservedly so than the other, And my attempts to bring proper economics to the albeit niche readership of the Investors Chronicle have not been met with complete derision.

Such episodes show it is possible for economists to gain some influence. What follows are some suggestions as to how or when this can be done.

First, economists cannot hope to challenge beliefs that are part of people���s self-identity. If you tell someone ���economics says you���re a twat��� you���ll not get a sympathetic hearing even if you are bang right. This helps explain the success of Freakonomics and the failure over Brexit: nobody had strong prior beliefs about whether Sumo wrestlers cheat, but they did about the EU.

In this context, I have it easy at the IC. People might not want to hear they are fools but they do want to know ways of making money, or at least to stop losing it egregiously. I can therefore try to be Keynes��� dentist, offering humble but competent advice without telling them they are fools.

Secondly, try to appeal to facts rather than the consensus. If you say ���most economists believe x��� you are at best only inviting the question: why might they believe that? And at worst, you���re inviting a sneer at experts.

Instead, tell them hard facts. For example, Chris Giles��� statement that the UK trades 3.3 times as much with Spain as with Australia was a lovely clear way of alerting people to gravity models. And some of my more successful efforts have consisted in pointing out that some types of stock, such as defensives and momentum, do tend to beat the market. Facts aren���t just useful in themselves. They answer the question: what do you know? They get you a hearing.

Thirdly, be clear about what you know and what you don���t. Claiming to be able to forecast short-term GDP moves when you can���t, or proclaiming a ���Great Moderation��� when this was temporary luck due to a lack of shocks, have brought economists into disrepute. Equally, if R-squareds are low or correlations are variable, say so. You���ve got to know your circle of competence.

Fourthly, don���t talk down to folk. In the day job, I try to imagine my reader as an intelligent and sceptical non-economist: a professional person or successful businessman. (I���ll concede, though, that I don���t always do this on the blog.) When I write about cognitive biases, for example, I try to not to say ���this is why you���re stupid��� but rather: ���these mistakes have been seen in other people: be on guard against making them yourself.���.

Of course, even if economists could always follow this advice (and I don���t claim to do so myself), they won���t always succeed. It���s difficult to talk to those who won���t listen, and there are few channels through which economists can talk even to those who want to listen. Our media (including the BBC) selects for blowhards rather than sober minds ��� a problem not confined to economics: how much influence do philosophers or sociologists have on the public discourse?

Economists will always have a tough job in the public sphere. Perhaps, though, there are some ways in which we might make it less tough.

February 1, 2018

Brexit: an unending dream

Simon says Brexit is a fantasy:

There is nothing about the case for Brexit that is based in reality. This is why everything Brexiters say is either nonsense or untrue.

This poses the question: will they ever acknowledge reality? I���m not sure they will.

Let���s say, for the sake of argument, that Brexit proceeds without massive glitches such as hold-ups at ports but otherwise much as Remainers expect (pdf)��� that is, we get slower growth in trade and productivity than we otherwise would. This implies weaker trend growth than otherwise. If we are to be five per cent worse of in the mid-30s than we would had we remained, we���d get average growth of (say) 1.6 per cent rather than (say) two per cent per year.

But the thing about counterfactuals is that nobody sees them. In 2035 there���ll be no Jim Bowen saying ���here���s what you could have won���. There���ll be no ���a-ha��� moment of proof that Brexiters were wrong, even if (arguendo) they are.

And this will bring a host of cognitive biases into play. Once we have bought something, we invent reasons to justify our choice. This is especially true for things we���ve strived hard for. As Dan Ariely put it in Predictably Irrational, ���the more work you put into something, the more ownership you begin to feel for it.��� This is the Ikea effect (pdf). And it���s amplified further by the fact that if a belief is part of our identity, we are especially loath to ditch it.

Brexiters, then, are likely to play up the benefits of being an ���independent people���. And they can easily attribute slowish growth to other causes: inadequate infrastructure or training, a lack of entrepreneurship and so on. Such blame will not be wholly wrong.

As Leon Festinger and colleagues showed, even the clear failure of a prophecy does not necessarily cause its believers to recant. This is likely to be especially true of Brexit, as the failure might not be glaringly, irrefutably obvious.

Asymmetric Bayesianism, choice-supportive bias, the endowment effect, ego involvement and dissonance reduction might combine powerfully to stop Brexiters recanting.

There���s more: adaptive preferences. We���ll get used to mediocre growth and resign ourselves to it. As John Band tweeted:

In 30 years time British people will just plain have forgotten that the country used to be about as rich as France, rather than benchmarking itself against Poland and Portugal.

Facts rarely settle political debates. This might be especially the case with Brexit.

January 30, 2018

Picking your own facts

The government���s own research says that leaving the EU will make us poorer in every scenario modelled, except presumably the fairies and unicorns option favoured by the government.

Rightists have responded to this by claiming that economists know nothing. For example, Iain Martin tweeted that long-term forecasting is impossible ��� thus failing to distinguish between conditional and unconditional forecasts ��� and Jacob Rees-Mogg claimed that the economy���s better than expected performance last year showed that gravity models are ���comprehensively wrong.*���

There is, though, a big problem with taking this anti-economics stance. Stephen Bush makes an excellent point when he says:

the thing about going "economists, what do they know, eh?" is it does make it a tad harder to argue against the whole Corbynism thing.

I���d like to amplify this. It���s plausible that economists��� knowledge about trade is more robust than our knowledge of (say) Laffer curves.

The gravity model has been described (pdf) as ���one of the most empirically successful in economics���. It tells us that countries trade massively more with their neighbours than with others, and that it is therefore unlikely that freer trade with far-off countries will compensate for any loss of trade with the EU. This is especially the case because we also know that national borders significantly reduce trade, and that only very deep trading agreements that go far beyond mere low tariffs (such as the EU���s single market) significantly boost trade.

Our knowledge of trade ��� on which hostility to Brexit is founded ��� is pretty OK.

Compare this to our knowledge of Laffer curves. This is more imprecise, not least because the top tax rate didn���t change for years and so we have no UK data to go on. The IFS, for example, says that Labour���s proposed 50% top tax rate ���could raise or cost ��1-2 billion a year in revenues���. And we have other evidence that revenue-maximizing top tax rates might in fact be very high, even on internationally mobile workers (pdf).

The point here is simple. You cannot invoke economists to argue against higher top tax rates but discredit them when discussing Brexit, because gravity models are founded on better evidence than Laffer curves.

By all means, be sceptical about the nature of economic knowledge generally. Or even admit that you���re basing ideas on non-economic ideas. But don���t pick and choose the evidence according to your ideology.

* In fact, this is bollocks. Insofar as the economy did better than expected last year, it���s got nothing whatsoever to do with the failure of gravity models. It���s because borrowing costs did not rise as a result of Brexit as (eg) NIESR had assumed (pdf); because the euro zone grew more than expected; and because households dipped into their savings to sustain consumption.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers