Chris Dillow's Blog, page 45

March 27, 2018

The socialism of moralizing fools

How can the Labour party have gotten into such a mess that it can be credibly accused of anti-Semitism? An under-appreciated part of the answer, I suspect, lies in the fact it is dangerous for politics to be seen as a moral project.

I mean this in three senses.

One is that some of the left has adopted the cause of Palestinian rights in the way my generation became active in the anti-Apartheid movement ��� as a moral crusade, a simple matter (in their minds) of right and wrong. Of course, it is trite to say that there���s a distinction between anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism, and rationally there is. But an interest in Israel-Palestinian affairs does not often enhance one���s rationality. Some of the most passionate pro-Palestinians have blurred the distinction.

Secondly, there���s a form of moral self-licensing. If you believe you���re the good guy acting for a good cause, you can sub-consciously give yourself a license (pdf) to behave badly: this was one psychological mechanism behind the Oxfam debacle. This, I suspect, has been Corbyn���s problem. His belief in Palestinian rights and his active anti-racism has led him to be insufficiently sensitive to some anti-Semitic tropes on the left.

There���s something else. That notorious mural contained a big truth ��� that, in capitalism, some are the oppressed and some are the oppressors. This would be just as true, though, if the oppressors had been depicted as George Clooney lookalikes rather than hook-nosed Shylocks.

The point here is that capitalist oppression is structural. Workers are not exploited because capitalists are bad people. Instead, exploitation is an emergent process ��� it arises from the nature of capitalism, independently of anybody���s intentions. Marx was clear on this. The worker���s unhappy condition, he wrote ���does not, indeed, depend on the good or ill will of the individual capitalist.��� Instead, he continued:

Free competition brings out the inherent laws of capitalist production, in the shape of external coercive laws having power over every individual capitalist. (Capital Vol I Ch 10, part 5)

The problem with capitalism, in other words, is a systemic one. It has little to do with the character of individual capitalists. In fact, they, like workers, are constrained by the system. Capitalism is about structures and processes, not (primarily) morality. Inequality hasn���t increased since the 80s merely because bosses have become greedier. It���s because of processes such as financialization (pdf), technical change, globalization and the decline of trades unions and atomization of labour.

It is very easy for leftists to forget this (I do so myself sometimes) or not to know it in the first place and instead to adopt a moralistic account in which workers are exploited by greedy bosses and bankers. This, however, opens the door to anti-Semitism; once you start talking about greed you are only a few steps away from anti-Semitic clich��s. Of course, many don't take those steps, but a few do.

Moralizing about capitalism carries another danger. It���s that economic systems rarely collapse simply because they are immoral. It was the guns of the Union army that defeated slavery more than the words of Frederick Douglass. And feudalism did not give way to capitalism because it was morally inferior. The job of replacing capitalism with socialism, by this reckoning, requires much more than moralizing. It requires the creation and expansion of socialistic institutions. Bleating about morality is little help here.

It has become common in the last few days to quote August Bebel: anti-Semitism is the socialism of fools. I���d add that it���s the socialism of moralizing fools.

March 22, 2018

"The country"

On the Today programme yesterday Justin Webb asked Yvette Cooper: [do] ���you think Jeremy Corbyn will keep this country safe?��� (1���57��� in).

From one perspective, the question is utterly absurd, because what is jeopardizing the country is not Corbyn but austerity. It���s plausible that this is killing tens of thousands of people by underfunding health services, driving some to suicide and contributing to a health crisis in deprived areas. And this is not to mention the underfunding of flood defences and the police that threaten harm to thousands.

Security policy is not the only way in which a government keeps its citizens safe. It also does so by health and welfare policies. Under the Tories, the latter are jeopardizing the country. To the extent that this is the case, Corbyn will increase the country���s safety by relaxing austerity.

In this sense, the question Webb should have asked is: is the country safe under the Tories?

Why, then, was his question even remotely plausible?

A benign possibility ��� which gains credence from the context ��� is that Webb was considering only external threats such as from Russia; he just forgot to add these words to his question. Maybe this exculpates him in this case. But I���m not sure it applies to everybody whose asking similar questions. The fact is that far more Britons��� health and safety are being threatened by austerity than by Russia or Islamist terrorists.

Perhaps there are two other things at work here.

One is a form of reification, which regards ���the country��� as an abstract entity comprising something other than its inhabitants. On this view, even minor attacks from outside threaten ���the country��� more than policies which kill thousands because they undermine the integrity of the nation.

It���s this reification that has allowed the right for decades to present leftists as unpatriotic. The fact that the left wants what it believes to be best for British citizens is not regarded as patriotism. Instead, its refusal to subscribe to myths of our glorious history (for example questioning the morality of the British Empire) and its reluctance to go to war are seen as attempts to undermine national pride. (In truth, the left has often not helped itself here).

But there���s something else. For centuries, talk of ���the country��� has excluded the poor. C.B Macpherson wrote of 17th century puritan attitudes that ���the poor were not full members of a moral community...They were in but not of civil society.��� (The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism, p226-27.) We see echoes of this today. When Tories tell us that ���the country can���t afford��� high welfare spending, they implicitly exclude welfare recipients from their perception of ���the country.���

Such talk helps to equate the national interest with the interests of the rich: it is very easy to convince oneself that ones��� own interests are also the public good. Once you���ve done this, it follows that Corbyn is indeed a threat to the national interest and a traitor. Conversely, the fact that the Tories take thousands of pounds of Russian money does not at all bring into question their patriotism because, in defending the rich the party also defends ���the country.���

The idea that Corbyn is unpatriotic or worse whilst the Tories are patriots rests upon a very questionable conception of what is ���the country���.

Another thing: Being neither a military man nor a newspaper columnist I am unqualified to speak of the merits or not of Corbyn's defence and security policies. Let's suppose though - arguendo - that these are weaker than the Tories. We then face a choice between thousands of deaths under the Tories or (barring talk of catastrophe which I find implausible) a handful more Skripals. If we are to be faced with this sort of trolley problem, I favour the latter.

March 21, 2018

The free speech dilemma

What role should social pressure play in the policing of free speech? Two things I���ve seen recently pose this question.

One is the racist harassment of Rufaro Chisango at Nottingham Trent University. I like to think that in better places and times those racist twats would have been swiftly suppressed by violent force by fellow students. Ms Chisango would, I suspect, gain much more confidence from knowing that her friends and neighbours have her back than she���d get from having to appeal to slow, impersonal and often incompetent university authorities or the police.

The other is the conviction of Mark Meechan for what seems to have been a bad joke. I agree with Adam Wagner that this is a bad idea. Criminalizing ���gross offence��� means giving too much power to the police to suppress unpopular ideas or ill-judged language. A more appropriate response would be to either ignore it and condemn such people to obscurity, or to just tell them they are wrong.

Such social pressure has worked well in the case of David Irving. He should be legally free to deny the holocaust, but the rest of us are entitled ��� and correct ��� to treat his as a pariah.

I���m even relaxed about most cases of no-platforming. Nobody has a right to speak at (say) a students union, any more than I have a right to a column in the Telegraph. A right to speak does not give the rest of us an obligation to host you.

Nor does that right entail freedom from the consequences of exercising it. You have a right to speak, and the rest of us have a right to tell you forcefully that you���re talking shit or to ignore you.

In fact, if the marketplace of ideas is to work, bad ideas must be weeded out. This is done by vigorously opposing them.

All this leads me to think that we should police speech not with the law but with the force of others��� opinion ��� either shunning them or opposing them depending on context.

Except, except, except. Here are four counter-arguments:

- Some privately-provided platforms are so widespread and important that withdrawing them is, as Robert Sharp says, a form of ���privatized censorship.��� He���s talking of Facebook���s banning of Britain First. They deserve no sympathy, but there���s a slippery slope here: if Facebook can ban them, it can ��� as Robert says ��� also censor others.

- Private sanctions against speech we don���t like can be excessively harsh. For example, I wouldn���t want firms to be able to sack employees just because they have opinions their employers don���t like.

- There���s a point, perhaps not easily defined, at which vigorous and widespread opposition becomes bullying: was Mary Beard bullied after her (I think) ill-judged tweet about ������civilized��� values���? I���m not sure. But women are especially vulnerable to an ugly mob rule.

- John Stuart Mill had a point in warning us of the tyranny of the majority. This he wrote, is

more formidable than many kinds of political oppression, since, though not usually upheld by such extreme penalties, it leaves fewer means of escape, penetrating much more deeply into the details of life, and enslaving the soul itself. Protection, therefore, against the tyranny of the magistrate is not enough; there needs protection also against the tyranny of the prevailing opinion and feeling; against the tendency of society to impose, by other means than civil penalties, its own ideas and practices as rules of conduct on those who dissent from them; to fetter the development, and, if possible, prevent the formation, of any individuality not in harmony with its ways, and compel all characters to fashion themselves upon the model of its own. There is a limit to the legitimate interference of collective opinion with individual independence; and to find that limit, and maintain it against encroachment, is as indispensable to a good condition of human affairs, as protection against political despotism.

Like other tyrannies; the mere fear of this power can be repressive. I fear it has led to a diminution of worthwhile opinions such as Oakeshottian conservatism or free market egalitarianism.

My point here is that we face a genuine dilemma. On the one hand, there���s much to be said for using social rather than legal sanctions against speech we don���t like. But on the other, those sanctions can be as excessive and misapplied as legal ones.

Dilemmas such as these are, I think, under-debated. Everybody is so keen to press their own point of view that we tend to miss a big issue ��� of how best to create a genuine healthy public discourse in which all voices are heard whilst at the same time ensuring that the marketplace for ideas selects against bad ideas.

March 20, 2018

Centrists & capitalism

James Kirkup in the FT has a nice piece saying that the centre-left needs more than just whines about Brexit and Corbyn, however justified these might be, but also needs a new economic model. I agree.

Successful political parties need an analysis of capitalism or ��� if you prefer ��� an economic narrative: Thatcher in the 70s had one, as does Corbyn today.

And to its credit New Labour also had one: some leftists tend to forget there was much more to the party then than ���Bliar/war criminal���.

New Labour believed that globalization and technical progress were tending to increase inequality by depressing demand for unskilled work and raising demand for skills. This lay behind policies such as tax credits and the minimum wage (to top up wages that were being driven down by globalization whilst preserving work incentives) and the expansion of higher education.

Such a project had much validity. From today���s perspective, however, it is incomplete in at least three ways:

- It is insufficiently critical of the uber-rich. Peter Mandelson was famously ���intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich as long as they pay their taxes." And Gordon Brown fawned over top businessmen. What they didn���t see was that top-down managerialism can worsen economic performance, and not just by contributing to financial crises.

- It failed to see that a degree, whilst perhaps necessary for a decent job, is not sufficient. The universities��� strike reminds us that even educated erstwhile ���middle class��� workers face oppressive management, stagnant wages and little hope of owning property.

- It took for granted capitalist and failed to anticipate (as in fairness did almost everybody else) that productivity would stagnate for years. It is now no longer sufficient ��� as Gordon Brown thought it was ��� for governments to merely offer a stable policy framework and supply of skilled labour. We need more than that to raise growth.

Blair���s achievement in the 90s was to recognise that Labour must adapt to a new economy. It must do so again today. But it is John McDonnell who recognises this fact whilst centre-leftists seem not to. Admirers of the Great Modernizer seem to be living in the past.

Which brings me to an issue. James writes:

Ownership��� should be wider. You cannot ask people to back an economic settlement in which they have no stake. And this is about more than houses. The UK needs a real stakeholder economy for the 21st century: more tax breaks to encourage more employee share schemes to mirror those for senior executives. If it���s good enough for the board, it���s good enough for the rank-and-file. Community ownership trusts could hold equity issued by public companies and handed to their customers.

This is good. More ownership for the ���rank and file���, however, means less for existing owners. To justify this, you need to show that their ownership is unwarranted. And that requires a deeper critique of capitalism than the centre-left currently seems to offer.

But there���s something else. The difference between a ���real stakeholder economy��� and full socialism is one of degree only. There���s a perhaps indefinable point at which one shades into the other. James can support such policies as ways of improving capitalism, but I can do so as a form of interstitial transformation (pdf), or accelerationism, of the economy towards socialism.

Of course, there���ll be disagreements about how far and how fast we travel down this road. But let���s get on the road and find out just what these are. It���s not clear to me that such differences of degree justify splitting the Labour party.

March 17, 2018

The illusion of knowledge

More information does not mean that we make better decisions, or even good ones.

Some laboratory evidence for this comes from some experiments (pdf) at Princeton. Alexander Todorov and colleagues asked subjects to predict the results of basketball games. Half of them were told the teams��� records that season and the half-time score in the match concerned. The other half were also told the names of the teams. Those who were told the names made worse predictions but with more confidence than those who weren���t. ���More knowledge can decrease accuracy and simultaneously increase prediction confidence��� they concluded.

A couple of examples from my day job corroborate this. Economists at the University of Mannheim show that even sophisticated investors buy expensive but poorly performing actively-managed funds. And economists at the University of Maryland show that when informed investors are given advice from a portfolio optimization tool they trade more often without improving investment performance.

You might think these examples are small beer. But a similar thing might have lain behind some of the most catastrophic decisions of recent years. If the government had had zero information about Iraq in 2003 rather than the military intelligence it actually had, it might not have gone to war. And if banks had known nothing they might have held fewer credit derivatives in 2007 than they were led to own by AAA credit ratings and risk management systems which told them that big losses would be 25 standard deviation events.

There are at least two mechanisms whereby more information leads to worse decisions.

One is that it encourages overconfidence, thereby emboldening people to do things they wouldn���t otherwise do, or to place bigger bets than they otherwise would. They fail to see that even good knowledge still leaves a lot of unavoidable uncertainty about the future.

A second is that information distracts people from using simple but effective rules of thumb of the sort described (pdf) by Gerd Gigerenzer (pdf). Simple rules such as ���invest in passive funds��� or ���don���t start wars��� work reasonably well: they at least protect us from terrible errors. Knowledge ��� and especially the illusion of knowledge ��� can lead us to think we can better than this, even if we cannot.

All this might seem abstruse. But in fact it bears upon two of this week���s big issues.

One is the idea of ranking universities by graduates��� earnings. Some people responded to my scepticism about this exercise by saying that if the rankings are prepared carefully they���ll be better than nothing. Weak ��� and necessarily out-of-date ��� information might however distract students from using effective heuristics such as ���go to the university with the best reputation you can given your grades���.

The other issue is the Skripal affair. People on all sides seem wholly confident about what happened and what the UK should do on the basis of information that seems to me to be scant at best. The heuristic ���if you don���t know, shut up��� goes unheeded. But then, perhaps in this case the evidence is not the point.

March 15, 2018

What do earnings tell us?

Sam Gyimah���s proposal that universities be ranked by graduates��� earnings has been criticized as missing the point that the purpose of a university education is more than personal enrichment. There are, however, other problems with it. I���ll take just seven:

First, at what stage of graduates��� careers do you measure earnings? If you do so soon after graduation, a course that produces lots of (say) investment bankers will seem better than one that produces lots of (say) barristers, because bankers earn big money quickly whilst barristers take longer to make it. If, however, you measure earnings later in life you risk using out-of-date information. The earnings of 50-somethings might tell us something about what university courses were like in the 1980s, but what does that tell us about them today?

Secondly, there���s a massive variation in earnings. Suppose that most graduates from a course earn average money, whilst one makes a fortune. Mean earnings will then be high, but median ones low. Which is the better guide for a student? The more we live in a ���winner-take-all��� or superstar economy, the bigger this problem will be.

Thirdly, qualifications alone do not determine earnings: a passing glance at your contemporaries will tell you this. As Bowles, Gintis and Osborne wrote in a classic paper (pdf):

Apparently similar individuals receive quite different earnings: a person���s age, years of schooling, years of labor market experience, parents��� level of schooling, occupation and income tell us surprisingly little about the individual���s earnings.

Many other things matter as well: soft skills; agreeableness (���being nice doesn���t pay��� says (pdf) Guido Heineck); narcissism; psychopathy; looks; and so on.

Maybe differences in all these will cancel out over large numbers. If, however, we are looking at particular courses in particular universities we are not dealing with very large numbers. And if average earnings are skewed by a few high earners, such differences will distort the results.

Fourthly, earnings can be enhanced by irrationality. In particular, overconfident people are likely to do better than ones with a rational assessment of their ability. A good university ��� surely ��� would teach its students to be rational. To the extent that it succeeds, though, it might impair its students��� earnings relative to a university that inculcates unjustified confidence. To this extent, earnings-based rankings will favour bad universities over good.

Fifthly, and perhaps relatedly, we know that people from posh backgrounds earn more than those from poor ones even with the same qualifications. If we do not correct for this, a university that accepts more posh students will look like a better one than one that accepts fewer.

Sixthly, even if we grant that we could measure how universities enhance earnings, by controlling for all the other factors that influence earnings, what would this tell us? It would tell us what universities were like a few years ago. But what use is that to someone considering attending now? What if a great lecturer or two has left, or arrived?

Seventhly, any university worth the name will encourage a sense of curiosity in its students. This, however, might not enhance their earnings. Lawyers might take on interesting pro bono work rather than stick to the dull day job; investment bankers will get bored and look for more interesting if less remunerative careers; or people might just ditch 60-hour weeks to do give themselves time for other things. Adam Smith wrote about compensating advantages because there really are such things.

Ranking universities by graduate earnings is, therefore, daft. It fails to heed the message of Jerry Muller���s new book, The Tyranny of Metrics. ���What is most easily measured is rarely what is most important��� he says. And, he adds, metrics can be gamed: all the above suggests that if universities are judged by earnings, they���ll want posher students; will encourage them to enter careers where financial success comes earlier; and will discourage rationality and curiosity.

When people are stupid, though, we must ask why. I suspect Mr Gyimah���s proposal is founded upon an unwillingness to face two uncomfortable facts.

One is that teenagers��� decisions to invest in their ���human capital��� are in many cases taken in conditions of almost perfect ignorance ��� not only about the future shape of the economy but also about their future tastes and preferences. A desire to rank universities by some objective-sounding measure represents an attempt to create an illusion of knowledge that hides this overwhelming uncertainty.

Also, our earnings are only very partially determined by our own efforts and choices. Luck plays an important role and merit might sometimes even be a handicap. Naturally, though, Tories want to overlook this fact.

March 14, 2018

The persistence of fiscal stupidity

Stupidity lives. This is the message of yesterday���s Spring Statement. Philip Hammond said:

If, in the Autumn, the public finances continue to reflect the improvements that today���s report hints at then, in accordance with our balanced approach, and using the flexibility provided by the fiscal rules I would have capacity to enable further increases in public spending and investment in the years ahead.

You shouldn���t need me to tell you this is daft. Government spending should not be constrained by the state of the public finances.

You don���t need to believe in MMT to see this. Bog-standard orthodox economics tells us the same. For one thing, when real interest rates are negative ��� as they have been since 2011 ��� governments can borrow a lot and still see its debt-GDP ratio fall over time. And for another, when interest rates are at rock-bottom, governments should relax fiscal policy to raise interest rates to give the Bank of England room for conventional monetary policy to work when the next slowdown hits.

Instead, the constraint upon government spending is inflation. If the government employs enough people, or raises their wages or spends enough on goods such as building materials, wages and prices will rise and that will push up interest and squeeze private spending.

It���s in this context that delaying public spending increases until the public finances improve is counter-productive. The best time to spend is when the public finances are poor because that is when the economy is depressed and inflation therefore not a problem. If you wait until government borrowing falls, you are more likely to increase spending when the economy is doing well and when capacity constraints are emerging. That���s when public spending is potentially inflationary.

Now, it���s unclear whether this is an argument against higher public spending soon. It might be that the very idea of aggregate spare capacity is mistaken, or perhaps capacity constraints (especially in a small open economy) don���t lead to much additional inflation. And there might well be a case for shifting the policy mix towards looser fiscal and tighter monetary policy.

What is very clear, though, is that the case for increases in public spending was greater a few years ago than it will be next year, unless we get a major surprise.

If the fiscal stance is determined by the state of the public finances, we���ll get exactly the wrong policy ��� too much tightness when the economy is slack, and too much looseness in a boom.

Government finances are not like household finances, simply because public spending is so big that it affects the rest of the economy ��� something which is not true of households.

This, of course, should be known by any first-year student. Hammond, however, went out of his way to explicitly state his error:

That is how responsible people Budget. First you work out what you can afford. Then you decide what your priorities are. And then you allocate between them.

That may be true for a household. But it���s plain false for a sensible government.

My story here, though, is not about economics: all this should be too obvious to need saying.

Instead, it���s about politics. The persistence of the household fallacy shows that wrong ideas are not driven out of public life and debate doesn���t raise the quality of policy. Quite the opposite. As long as they hurt the poor whilst cossetting the rich, governments can get away with anything.

March 12, 2018

Cultural costs of high house prices

Much has been written about how high house prices are reducing (pdf) home ownership and depressing real incomes. This is an economic menace: it depresses productivity and increases economic instability (pdf). But I wonder: does it also retard cultural and technological change?

I ask because the emergence of youth culture as we know it in the 1950s was the product of the fact that the post-war economic boom put money into the pockets of young people. As Billy Bragg says:

What happened in 1955, '56 was the first generation of British kids who were born during the war left school. And they left school at a time of high employment. So they were able to find work pretty quickly. So they were getting paid more, sometimes more than their parents. And they, you know - the only expense they had was giving housekeeping to their mom. So they had a lot of money to spend things on. So sales of cosmetics, of records, of clothes kind of took off in the mid-'50s. And this generation really is the first generation to identify themselves as distinct teenagers.

Friedrich Hayek said a similar thing. In The Constitution of Liberty he wrote that economic progress takes place ���in echelon fashion.��� New goods at first are ���the caprice of the chosen few��� and they then spread. He thought the ���chosen few��� were the rich. But they can equally well be younger people who are more open to new products and experiences: grandparents, for example, have iPads because their children and grandchildren got them first.

All this implies that if the incomes of the young are squeezed by high housing costs then we���ll see less cultural or technical progress. And this, I suspect, is just what we���ve got. The distinctive products and experiences we associate with millennials are small beer ��� literally so in the craft beers served in what we oldsters call short measures: coffee, avocado toast and free apps. This is not the stuff of cultural dynamism.

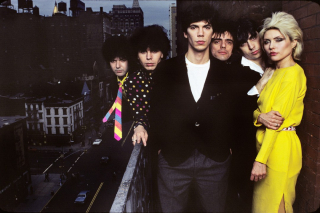

There���s more. Art and culture, as much as industry, benefits from agglomeration effects ��� the ability of creative people to live near each other. In the 60s and 70s countless musicians moved into rundown New York apartments where they could live cheaply whilst they honed their craft and waited for their break. Today, this is no longer possible in New York or London unless you have rich parents. As Chris Stein has said:

The biggest shame is that everybody���s gotta have a job to live in the city now. There���s no time to make art. How can you keep your credibility if you have some stupid job you hate and still be a radical?

Cheap housing gave us Blondie and Philip Glass. Expensive housing gives us Mumford and Sons*.

What it gives us in greater numbers, though, are drones - commute, work, sleep: repeat for 50 years. I know that PR-based surveys are unreliable, but it���s not wholly surprising that so many millennials are suffering quarter-life crises.

In this sense, expensive housing has totalitarian tendencies: it enforces uniformity. For some, this might be a feature not a bug. For those of us who value diversity, however, it is certainly not.

Now of course, all this is necessarily speculative. It���s a story about what hasn���t happened. But then, that is the very nature of opportunity cost: we don���t see the road not taken. And the road closed by high housing costs might well have been a pleasant one.

* I���m not saying that a rich background precludes musical genius; Nick Drake and Townes van Zandt are obvious counter-examples. It���s just that if you draw your talent only from the rich then you have much thinner pickings.

March 11, 2018

Immigration: the wrong battle

Jeremy Corbyn is being criticized for claiming that immigration cuts wages. I suspect his critics are right, if not quite for the reasons some of them might think.

Corbyn said he wanted to

prevent] employers being able to import cheap agency labour to undercut existing pay and conditions in the name of free market orthodoxy.

One can read this not as a call for immigration controls but for restrictions on employment agencies.

Such a reading, however, doesn���t exonerate Corbyn.

For one thing, social pressure and market forces have already reined in bad agencies. Transline ��� the supplier of labour to Amazon and Sports Direct memorably described by James Bloodworth in Hired ��� lost those contracts and went into administration last year.

And for another, he must have known that statement would be read as a claim about immigration.

And it���s here that he���s wrong.

It is the case that immigration does reduce the wages of some unskilled workers. But the effect is puny. As Jonathan Portes has said:

Immigration may have some, small, negative impact on wages for some low-paid workers. But the idea that immigration is the main or even a moderately important driver of low pay is simply not supported by the available evidence.

And this small downwards pressure on the lower end of wages is offset by upward effects upon higher wages. Net, immigration is not bad for the economy.

Now, Corbyn���s centrist critics will stop here. But they shouldn���t. It���s here that my complaint with him begins.

In one sense, politicians are like generals; one of their great skills is to choose the terrain on which to fight their battles. And in these words, Corbyn is shifting the battle to the wrong field. He is, in Gramsci���s words, taking a wrong move in the war of position.

What he should be doing is to argue that wages are being depressed not by immigration but by fiscal austerity and by dysfunctional capitalism: stagnant productivity; financialization (pdf), power-biased technical change; deunionization and so on*.

Even the slightest talk of immigration shifts the agenda against this. It moves the political battle onto the terrain that capitalists and Tories want it to be on. They want to distract us from the failures and injustices of austerity and (neoliberal?) capitalism by scapegoating immigrants.

The more we talk about immigration, the less we talk about capitalism. Labour cannot win a battle on this terrain. Once you concede that immigration depresses wages, you are allowing the right to offer tougher and more credible policies to combat it than you can. And you are distracting people from the real reasons why wages are low - reasons that Labour has some policies to combat.

Labour���s attitude to immigration should be much the same as its attitude to government borrowing: it should be silent about it because it doesn���t matter. In fairness to Corbyn, one of his great achievements in last year���s general election was to do just this.

The right, of course, already has a massive advantage in choosing the terrain; the right-wing press sets the agenda and the BBC follows. Labour therefore needs to be very careful not to add to this advantage. In this sense, Corbyn has failed.

* I���m not saying Corbyn should use these exact words. Another of the great skills of a successful politician is to translate technical economic language into words that resonate more with people.

March 7, 2018

Management vs managerialism

Stian Westlake made a very good point yesterday:

Attacks on managerialism sometimes (often?) become a sort of wholesale denial of the importance of management (which IMO is a mistake).

He���s right. Good management makes a big difference to productivity, wealth and even happiness.

We should, therefore, distinguish between management and managerialism. I���ll list just five such differences: these might be rather stylized and I���m perhaps exaggerating to make a point.

1. Managerialism contains elements of magical thinking and a Messiah complex: it believes that if the right man is in charge, success is assured. We see this in an extreme form in the ���Wenger out��� demands. What this fails to ask is: what exactly is the mechanism whereby bosses improve organizations?

Good management answers this question. It does not look for Messiahs: ���hire a genius��� is not a sustainable business model. Instead, it puts round pegs into round holes. If a company���s problem is an engineering one, you hire an engineer as a boss. If it���s a marketing one, you get a marketing man. Boris Groysberg has shown (pdf) that what determines firms��� success isn���t so much the ability of a boss so much as having the right man in the right job.

2. Managerialism believes there is a distinct skill of management that can be applied everywhere: we see this in the careers of people like Adam Crozier or Rona Fairhead who have jumped from industry to industry. As Protherough and Pick said:

Rightly we honour the memory of managers such as Jesse Boot, Dr Bernardo, Florence Nightingale, Thomas Cook, the Joseph Rowntrees or W.H.Smith���[But] the notion that they had in common a single talent which can be identified as ���managerial skill���, capable of ready transference between their different callings, is pure fantasy. That Dr Bernardo could equally well have run a chain of newsagents, or that Thomas Cook could just as readily have run a chocolate factory, is manifestly absurd. Yet the modern world believes as fervently in the transferability of management as it believes that management skills are separate and identifiable realities. (Managing Britannia, p 13)

Good management, by contrast, realizes that context matters. In The Tyranny of Metrics, Jerry Muller points out that the best performance indicators ���are embedded into a larger institutional culture.���

3. Managerialism imposes targets and discipline from the top down.

Good management, by contrast, listens to those on the ground. As Henry Mintzberg says:

Among the most important qualities of managers who truly lead is a captivating capacity to listen, really listen.

For example, Muller notes that performance measures work best when they are devised in cooperation with those who���ll be guided by them. To take his example, in hospitals they are based on collaboration with doctors.

4. Managerialism operates, in Protherough and Pick���s words at ���a high level of mental abstraction���; it talks of strategy and vision.

Good management, by contrast, is sceptical of this. It heeds Rosewell and Ormerod���s point that firms cannot know much about the long-term. Instead, it focuses upon facts and evidence. The measures of good management used by Van Reenen and his colleagues focus upon processes for measuring performance and responding to feedback.

5. Managerialism has an element of totalitarianism; it tries to apply its methods everywhere. It ignores the old medical saying, ���the dose is the poison���.

Universities offer a good example of this. These were one of the UK���s very few world class industries even back in the 1970s and 80s. They should, therefore, have been left more or less alone to carry on. Managerialism didn���t do this. The upshot has been increasingly expensive administration and demotivated academics.

Good management, by contrast, knows its limits. It knows that badly designed incentives can encourage people to game the system ��� for example when teachers ���teach to the test��� ��� or can crowd out intrinsic motivations such as professional pride. It knows, thanks to John Kay, that the direct path to a goal can sometimes be inferior to an oblique approach. And it knows what Jeffrey Nielsen said in The Myth of Leadership ��� that management can sometimes demotivate employees as they look to the top for guidance rather than use their own initiative.

It also knows that organizational capital and path dependence matter. When these are strong and favourable, a sensible manager will preside rather than rule. But when they are weak or adverse, even the best managers might fail. Warren Buffett has said:

When a management with reputation for brilliance gets hooked up with a business with a reputation for bad economics, it's the reputation of the business that remains intact.

He���s also said that if you have a great business even your idiot nephew could run it. Perhaps (and this is just a tentative hypothesis) it is only in intermediate cases that management makes a big difference.

Good management also knows that some things in particular respond badly to heavy-handed bosses. One of these is long-term work. Muller gives the example of the intelligence analysts tasked with catching Osama bin Laden. For years these had zero productivity and a 100% failure rate. Short-term targets would have shown them to be hopeless. Until they finally succeeded.

Another is creativity (pdf). Toru Iwatani, the creator of Pac Man, has said:

Japanese game companies used to be places of total freedom. We had almost no orders, except to make fun games.

That���s anti-managerialist. But it���s good management.

Now, I don���t intend this to be a complete list, nor a full definition of managerialism. I hope, though, that it���s made clear that there���s a big distinction between good management and managerialism. How we can get more of the former and less of the latter is a political project that doesn���t get the attention it deserves.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers