Chris Dillow's Blog, page 41

July 20, 2018

Capitalism as a fetter

I was a little disappointed to see Tony Yates��� reaction to Aaron Bastani:

Can we ditch 6th form debates and have someone arguing for evidenced based improvements to our policy portfolio please?

My disappointment is the failure to see that there is, if you like, a third way between utopian communism on the one hand and technocratic tweaks on the other.

It begins from the idea that ten years of stagnant productivity might mean we are now at the phase of capitalism that Marx foresaw:

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or ��� this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms ��� with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters.

If this is the case, then Tony���s reply to Aaron is half right. He���s right to decry utopianism and demand improvements to our policy portfolio. Where he might err, though, is in not seeing that capitalism itself is the problem. If so, we need quite radical solutions.

So, how might capitalism now be a fetter on the productive forces? Here are a few ways:

First, low investment and innovation might be due in part to the fact that these have external benefits which firms cannot internalize. William Nordhaus famously showed that capitalists capture only a ���minuscule fraction��� of the benefits of innovation. It might well be that one reason why techno-optimism co-exists with low investment is that firms are loath to invest for fear that their profits will be competed away by future innovations.

Secondly, it���s possible that tough intellectual property laws stifle innovation whilst protecting monopolies.

Thirdly, the failure to align managerial and shareholder incentives has led to a lack of productive investment. As Stutz and Kahle have shown, quoted firms today tend to be older and to invest less than their counterparts did years ago. In a similar vein, entrenched management acts as what Joel Mokyr calls a ���force of conservatism.��� Eric Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee say that "significant organizational innovation is required to capture the full benefit of���technologies." But bosses lack the incentives or the skills to undertake such innovations.

Fourthly, inequality ��� not just of income but of workplace power ��� might itself be a fetter on production. I���m thinking of (at least) three mechanisms here:

- It breeds distrust (pdf). The reduces growth in several ways. It might reduce the many transactions which depend upon trust. The fear of future expropriation or tax increases might deter investment and innovation. It might encourage capitalists to invest in guard labour or in political lobbying to entrench their privilege rather than in productive activity. It can lead to worse policy-making as populism increases because people no longer trust ���elites���: Brexit might be a consequence of high inequality.

- The high-powered incentives that lead to big CEO salaries can backfire. They encourage dishonesty, reduce creativity and divert management effort from hard-to-monitor tasks such as long-term innovation and towards easier-to-monitor ones such as short-term earnings management.

- Inequalities of wages within the workplace cause dissatisfaction (pdf), which demotivates employees and reduces productivity. Inequalities of power can have the same effect. They demotivate more junior staff, who expect to be told what to do rather than use their initiative. They can also suppress productivity by failing to fully exploit the dispersed fragmentary knowledge of ���ground truth��� which workers possess.

You might wonder: if all this is the case, how did capitalism ever grow? One answer comes from Schumpeter; growth was powered by an entrepreneurial spirit which has been supplanted by bureaucratic management. Another answer is that capitalism has changed. What worked when workers were unskilled drones operating physical machines does not work when skilled immaterial labour works with intangible assets. And thirdly, we must remember that capitalism grew fastest between 1945 and 1973, when it contained a big dollop of social democracy.

If this diagnosis is right, what���s the answer? For me, it would comprise a mixture of conventional supply-side policies, state support for innovation and worker coops, and measures to improve workers��� bargaining power such as a citizens income and full employment to incentivize labour-saving productivity. You might object that these aren���t very socialist. But they should be a stepping stone to socialism, a form of accelerationism. We can���t get to a communist utopia overnight.

July 18, 2018

On justifying policies

Much as I like Ash Sarker, I���m not happy with this recent thread of hers:

Lots of people have asked what I mean when I say I���m a communist. What I mean is that in the next 15 years, 1 in 5 jobs in the UK will be automated (1 in 3 in the North, and 40% in Hayes & Harlington). What does that mean for workers? it means that *either* 1 in 5 people are excluded from the means of survival, are consigned to the scrapheap and increasingly authoritarian and violent means are employed by the state to manage surplus populations. Or... we find a means to distribute the abundance generated by fixed capital for the good of all. We say that it���s bollocks that something as arbitrary as ownership can dictate whether homes, land, technology are for people, or for profit. in the past, we called that communism.

I���ll leave quibbles about her definition of communism to boring pedants. Instead, I have another problem: we should not ��� as far as possible ��� base our policy ideas upon economic forecasts. This is because forecasts, especially about the pace and direction of technical change, can be wildly wrong. To take just examples from Nobel laureates:

���The Soviet economy is proof that, contrary to what many skeptics had earlier believed, a socialist command economy can function and even thrive��� ��� Paul Samuelson, 1989.

���Macroeconomics��� has succeeded: its central problem of depression prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes��� ��� Robert Lucas (pdf), 2003.

���The growth of the Internet will slow drastically���By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet's impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine's��� ��� Paul Krugman, 1998.

The notion that robots will take our jobs might fall into this category. Certainly, there���s little sign of it happening now; business investment has flatlined in recent years whilst employment has grown and the OECD says (pdf) the UK has fewer robots than most developed countries. And it might not happen at all. As Acemoglu and Restrepo point out, any incipient tendency for employment to fall would tend to reduce wages and so incentivize employers to create jobs.

I don���t say this to dismiss Ms Sarker���s point. She���s bang right to highlight a risk. This matters because good policy-making (older readers might recall such a thing) requires policy-makers to heed the distribution of risks, not just central scenarios.

Let���s take a brief detour to another example. The OBR warned this week that ���the public finances are likely to come under significant pressure over the longer term, due to an ageing population and further upward pressure on health spending.��� As a central forecast this is questionable. But it���s surely a risk. So what to do about it?

The answer isn���t to jack up taxes immediately: we shouldn���t trash the economy on the basis of a dubious long-term forecast. Instead, one way to address the risk is to adopt policies to raise productivity: the more productive we are, the more we can afford of everything, including healthcare. Here there are countless possibilities even ignoring the obvious (ditch Brexit): better education and training; more infrastructure investment; better planning policy; stronger competition policy; better financing for entrepreneurs. And so on.

And here���s the thing. Most policies such as these can be justified on different bases: they are good things in themselves (education); they create jobs; they give customers a better deal. And so on. You can kick away fiscal forecasts and still justify them.

Which brings me back to Ash. ���Communist��� policies should be defensible on bases other than a forecast. Take for example a citizens income. Ash might support this as a way of ���distributing the abundance generated by robots���. But we could also justify it as: a way of supporting part-time workers or those in training; as a way of sustaining aggregate demand; or of empowering women and workers to walk away from exploitation; as a way of removing the stigma of being a ���benefit claimant���; or as a way of cutting the administrative cost of the welfare state. And so on. This does not mean the scheme is a magic bullet. It's not. It���s just that it can be defended from many perspectives: left, right, feminist and so on. Sure, it might also be a solution to the job losses and inequality caused by robotization. But to argue on those grounds alone is to horribly under-sell it.

I���d argue that workers��� democracy also fits this bill: it���s not just egalitarian in itself, but a way of improving well-being and productivity.

Of course, in saying this I���m not attacking Ash at all. I���m making a general point about policy-making. Good policies should be defensible on many grounds, simply because any single ground might give way (especially if it���s a forecast). To argue for a policy therefore requires you to adopt more than just one perspective.

July 17, 2018

Brexit as neoliberal politics

Many leftist remainers accuse Brexiters of being neoliberal. In one sense, this is questionable: "fuck business" is not a neoliberal sentiment, and nor is a desire for harsh immigration controls. In another sense, however, I suspect it is true: the Brexit campaign represents a triumph for a view of politics as mere marketing.

To see my point, start with an idealized conception of politics as the management of the public sphere. On this view, politicians are motivated by a sense of public service and they debate rationally and honestly about different conceptions of the public good and how to implement those conceptions.

(Many) Brexiters, however, have a different conception. To them, politics is simply about getting what you want by whatever means you can, regardless of cost. Politicians with a sense of public service would not have broken electoral law on spending limits, or lied about immigration or about the economic effects of Brexit. We could have had a rational debate in the referendum about the trade-off between sovereignty and prosperity. But we didn���t. Those Brexiters who now privately claim that the loss of ���hundreds of thousands of jobs��� would be worth it didn���t say so at the time. For them, getting what they wanted trumped duties of honesty. Of course, the Brexiters might have won an honest and legal campaign, but they never took that chance.

In this sense, Brexit is like spivs mis-selling financial products. All that matters is that the sale gets booked, that the seller gets his bonus. The cost of achieving those sales ��� the future fines that���ll be paid by some other mugs - doesn���t matter

Nor does it matter whether those sales represent the interests of the customer. The ���will of the people��� must be obeyed regardless of how that will is formed or at what cost to the public realm. It is only after you���ve convinced people to buy your snake-oil that the customer is king.

Nor do practicalities such as the difficulty of achieving Brexit matter. Implementation requires hard work and a diligent regard for the public good. Such virtues fit uneasily with the mentality of the salesman. In this sense, there���s an analogy between Brexit and Build-A-Bear���s recent ���pay your age��� promotion. Both were great marketing tricks marred only by a neglect of whether one could actually deliver the offer. But who cares when marketing is all that matters? Delivery is somebody's else's problem.

I call this neoliberal because one feature of that much-abused idea is the belief that all of society must be dominated by the crudest conception of corporate behaviour ��� that of the spiv conning his punters regardless of consequences - rather than by any sense of public duty.

It���s neoliberal in another sense. For me, one feature of neoliberalism is the elevation of the goods of effectiveness over the goods of excellence, to use MacIntyre���s distinction. An excellent politician would be one capable of rational persuasion and good administration. For the effective politician, all that matters is winning, achieving power however you do so.

It���s in this context that we should understand Brexiters contempt for the Electoral Commission, experts and civil servants. All of these are (imperfectly of course) custodians of the public good. But this doesn���t matter: the sale is everything.

Here, I���d distinguish sharply between Thatcher and Thatcherite Brexiters. Thatcher might have subscribed to what we now call neoliberal ideas. But she didn���t use the neoliberal methods I���m discussing here. Although I disagree with almost everything she did, I wouldn���t call her dishonest nor heedless of the difficulties of implementing her ideas. These huge differences between her and her epigones tell us how far politics has declined during my adult lifetime.

July 11, 2018

On class separation

The Times obituary of Lord Carrington says:

More commonly, he found himself sleeping in a hole beneath his tank with his four crew who came from poor backgrounds and had suffered hardship during the pre-war years. The experience shaped his politics, he said later. ���You could not have got a finer or better lot than they were. They deserved something better in the aftermath of the war.

This was a common sentiment. In exposing posh men to the working class, military service increased their sympathy for the poor ��� and as Adam Smith said, sympathy is the basis of our sense of justice. For this reason (among many others discussed by Walter Scheidel in The Great Leveler) the war led to big fall in inequality.

Herein, though, lies perhaps an under-appreciated social change in recent decades ��� an increased separation of the classes. I don���t just mean geographic separation, though this is important. I mean separation in the workplace. Years ago, the classes would meet at work. In offices, posh men would meet less educated women in the typing pool: think of the Mad Men office. In manufacturing, middle class managers would rub shoulders with workers. And even in investment banks, there really were ���barrow-boy���-type traders alongside old school tie-types.

This now is now longer so much the case. Many of us are in occupations where we only meet folk of similar class. And thanks to a lack of social mobility, posh people are unlikely too meet many from a different class origin. The only working class person a journalist might meet at work is the cleaner. For all the talk of diversity, many posh people now work in homogenous offices. As Daniel Cohen writes:

Only recently, workers, foremen, engineers and owners were connected by relationships that, though sometimes antagonistic, allowed each group to evaluate where it belonged in a shared industrial world. Now, engineers are in consulting firms, maintenance workers are in service companies, and industrial jobs are subcontracted, mechanized or relocated. (The Infinite Desire for Growth, p148)

I suspect this has contributed to increased inequality.

One obvious route is via increased assortative mating; middle-class men now marry other middle-class women rather than their (working-class) secretaries. That has increased inequality (pdf).

Another mechanism is the ���out of sight, out of mind effect���. If the poor never see the rich, they���ll never appreciate just how great inequality is. For example, Sorapop Kiatpongsan and Michael Norton have shown (pdf) that in 16 countries, the ratio of CEO to workers��� pay is massively greater than people estimate it to be.

By the same token, if the rich are out of sight, envy and resentment will be directed instead at the people who are in sight, such as benefit claimants.

But there���s also the reverse Carrington effect: greater class separation means less sympathy and so less taste for redistribution among the rich.

One aspect of this consists of the othering of workers. Because posh people have so little direct knowledge of working people, they impute all sorts of bad habits to them, such as lack of aspiration, poor diet and racism ��� even though the latter especially is also found in posher people.

Such imputation also serves a reactionary function, as the belief that workers have ���legitimate concerns��� helps to popularize anti-immigration policy and to displace more radical agendas. There���s just one problem with this. It���s not true. Attitude to immigration have softened markedly in recent years (table 6 of this pdf). And in new research Matthijs Rooduijn concludes (pdf):

There is no consistent proof that the voter bases of populist parties consist of individuals who are more likely to be unemployed, have lower incomes, come from lower classes, or hold a lower education.

Ignorance of workers, then, might well contribute to both inequality and a misreading of politics.

All this said, things aren't so clear. Mere proximity to workers doesn���t necessarily give you great knowledge of them: David Astor, the mega-rich editor of the Observer in the 50s, for example was shocked to discover that his staff had mortgages. Nor does it always generate sympathy. Perhaps the opposite. One reason for Thatcher���s popularity among much of the middle class in the 1970s was that managers knew workers well and saw them to be lazy, bolshy and greedy.

All I���m suggesting is a possibility ��� that there has been increased separation of the classes since (say) the 1970s; that this might have political and social effects; and that all this is under-appreciated.

July 10, 2018

Right-libertarians as counter-advocates

Daniel Hannan tweeted recently:

Libertarians want to break oligarchies, expand opportunity and let wealth spread. I can���t think of any political movement where the gap between what its supporters believe and what they are imagined to believe is wider.

Now, if people widely and persistently misunderstand you, the failing is likely to be yours as well as theirs. Mr Hannan should therefore ask: what are we right-libertarians doing wrong?

For one thing, they are keeping bad company. Bryan Caplan once wrote that there is a ���libertarian penumbra��� ��� a set of beliefs that are logically separate from libertarianism but which many libertarians happen to believe. One of these, for example, is an (excessive?) interest in IQ research ��� despite the fact that no correlation between IQ and life-outcomes suffices to justify our social system. For some leftists, this alone helps discredit right-libertarians.

In the same vein, right-libertarians are seen as shills for the rich ��� an image reinforced by the refusal of the IEA and Adam Smith Institute to say who funds them.

If being on the side of workers were to become a criminal offence, there���d not be enough evidence to convict many right-libertarians, Certainly, few are guilty by association.

Yet other associations are much worse. At least a few right-libertarians have supported Trump, others border upon the racist, and Christopher Freiman says many favour immigration controls despite the fact that the liberty to live where one wants or hire whom one wants must be important freedoms. And yet others take an interest in the sex redistribution cause.

Of course, this isn���t true of all or perhaps even most right-libertarians. But a few (some? many?) cases makes them look like a tribe of cranks. This matters, because when you are espousing views a long way from the mainstream, people are apt to think you cranky anyway so such examples reinforce that belief.

Just as significant as the associations some right-libertarians have are those they don���t have. Take for example the #Metoo movement. This is essentially expressing women���s Nozickean right of self-ownership. You���d expect, therefore, libertarians to be enthusiastic supporters of the movement. Similarly they should be vocal advocates of gay rights and of Black Lives Matter; being killed by a cop is a significant infringement of freedom. For every self-professed libertarian who is, however, there is perhaps another bleating about identity politics.

Yet another reason is that right-libertarians have some asymmetric sensibilities. On the one hand, many seem highly attuned to the dirigisme of Brussels, so much so that they took money from that noted libertarian Vladimir Putin to escape it. And yet they are blind to the much greater infringements of freedom that occur in workplaces. It���s as if they actually want to conform to Corey Robin���s description of conservatives as those who want to entrench private sector hierarchies, rather than break them as Hannan claims to want. I sense they would rather defend property than freedom

In this context, there���s another curious blindspot. Right-libertarians often channel Hayek to argue that the virtue of markets is that they aggregate the fragmentary information of dispersed individuals. Often they are right. But markets are not the only technology for doing this. Democratic control of workplaces can do a similar thing. Logically, right-libertarians should therefore support worker coops. But this is not exactly what we see.

Yet another blindspot is the failure to see that a sustainable market economy requires particular pre-conditions, such as rough equality of bargaining power; anti-monopoly policy; obstacles to cronyism; and measures to encourage socially useful innovation.

Without such pre-conditions, a ���free market��� economy will be dysfunctional and unpopular. Too many right-libertarians don���t get this. Like Brexiters ��� they are in many cases the same people ��� they will the end but not the means.

Hannan is right to say that freedom entails the breaking of oligarchies and spread of wealth: I suspect the causality runs both ways. The problem is that right-libertarians are terrible at arguing for this. In fact, I suspect they are even counter-advocates: they are so bad at making their case that their efforts to do so weaken support for freedom. Of course, you can point me to exceptions to this. My impression, though, is that that���s just what they are ��� exceptions.

July 8, 2018

What Southgate teaches us

Whatever happens next, this has been a great World Cup for Gareth Southgate. What does this tell us?

The first thing is that, as William Goldman said, nobody knows anything. When Southgate was appointed, the reaction was underwhelming. Nobody said ���this guy will take us to our best World Cup performance since 1990.��� This fits a pattern. ���Arsene who?��� asked the press when Arsenal appointed Wenger; Sir Alex Ferguson was famously one game away from the sack; and Leicester���s hiring of Claudio Ranieri was greeted with scepticism and certainly not with talk he���d win the title.

The point generalizes. Countless best-selling books and films were rejected by publishers and studios, great music acts were ignored, and Dragons Den has turned down profitable ideas.

Great success is largely unpredictable. Pundits and experts know less than they pretend.

Secondly, what matters when you���re hiring a manager isn���t so much the quality of the manager but the match between his abilities and the job requirements. Southgate might not be the best manager available, but he���s the right one.

One reason for the lukewarm reception to his appointment was that his CV was less impressive than that of many of his predecessors most of whom had some success in club management. But at least of the qualities of good club manager are irrelevant to international management. An England manager cannot plug gaps in his squad by going into the transfer market, and he cannot work intensively with his players day-in, day-out. It���s possible therefore that better preparation and more relevant experience for the job is working well with the under-21s.

Again, this generalizes. Boris Groysberg and colleagues compared (pdf) the careers of former managers of General Electric. All had similar impressive CVs, but their success in subsequent jobs varied a lot. This was because some managers were better matched to the job than others. If you want your firm to grow, you���re better with a marketing man than a cost-cutter. If you want to improve the efficiency of your firm, though, you���ll be better off with an engineer than a marketing guy. And so on. It's the match that matters, not just the man.

Thirdly, Southgate���s success reminds us that even in our anti-meritocratic world there is a place for what Alasdair MacIntyre calls internal goods. Southgate is a modest and not especially ambitious man; he claims not to have wanted the England job. Rather give us bullshit drivel about drive and passion he has quietly and diligently prepared the England squad as well as he can . He has pursued internal goods ��� the mastery of a particular practice.

In this sense, he is the diametric opposite of so many characters who dominate and deform our public life ��� those who seek what MacIntyre calls external goods of wealth, fame and power. The obverse of Southgate is Boris Johnson, a noisy charlatan who never bothered with the hard work of preparing for Brexit.

Fourthly, in being by all accounts a nice man, Southgate has undermined the public image that one has to be unpleasant and ruthless to succeed in management: contrast him to the crude image portrayed by Alan Sugar or Karen Brady in The Apprentice ��� an image lots of businesspeople hate.

That said, the aggregate data isn���t clear here. Guido Heineck has shown that agreeable people tend on average to earn less than others. This might, however, be because they are less good at bargaining rather because they are less effective at their jobs.

It���s possible, then, that Southgate���s success might lead to managers behaving better at work, in the knowledge that nice can succeed.

If you���re with me so far, perhaps you shouldn���t be.

Things might have turned out very differently for England. We might well have lost the penalty shoot-out against Colombia: David Ospina came close to saving all the penalties. And even a mediocre Swedish team might have got a result were it not for some great saves by Pickford.

But they didn���t. The acclaim Southgate and England are getting is in part due to the outcome bias. Good results cause us to exaggerate a team���s strengths and overlook its weaknesses. Success is celebrated even if it���s due to luck. And our urge to see patterns in everything leads to articles such as this one, asking what we can learn from such luck.

As I said, nobody knows anything.

July 6, 2018

On egocentric framing

We had great weather on the May Day bank holiday. This meant that pretty much everybody around here decided to drive to Rutland Water, with the result that there were hours of gridlock on our usually empty roads.

This was a common mistake. It���s what David Navon calls the egocentric framing error ��� the tendency to think only from one���s own perspective. It seemed a good idea to each person to drive to Rutland Water. Thousands of these, however, failed to ask: ���won���t everybody else have the same idea?��� And so they spent hours of a beautiful day stuck in a car.

You might well have made a similar mistake if you���ve been stuck in traffic on a motorway. You decide to change lanes only to see the lane you���ve left move faster because other people had the same idea as you and so emptied a lane.

This costs people real money as well as time. One of the strongest mispricings in stock markets is the tendency for newly-floated stocks to be over-priced and so fall (pdf) in the months after they were issued: to take just three cases that immediately spring to mind, AA, Pets at Home and Saga are all lower now than when they were floated, despite a strong rise in the overall market.

One reason for this, I suspect, is egocentric framing. Investors think ���hey, this is a great investment��� without stopping to consider things from the seller���s point of view. They don���t ask: if this is such a good business, why are the folk who know most about it so keen to sell?��� Exactly the same error can cause people to trade stocks too much. In fact, it can cause people to become money pumps as they fall into the ���two envelopes��� error.

Bad chess or (I gather) poker players often make the same mistake. They pay too much attention to their own next move and neglect to consider their opponents��� strategy.

A variant of this error is our tendency to be insufficiently self-critical of our own ideas. Like photographers, we fall in love with our models because we don���t sufficiently ask: how do these ideas look to others? We���re especially prone to this if we associate ourselves with like-minded people. When I recently complained about centrists not seeing that they are ideologues like the rest of us I was, in effect, charging them with the egocentric framing error.

There���s a reason why I say all this today. Many people agree with Ian Dunt in thinking the EU will ���undoubtedly reject��� Theresa May���s plan to have, in effect, membership of the single market for goods but not services. One reason why they believe rejection is likely is that the government has spent so much time negotiating among itself that it has neglected the question: what might be acceptable to the EU? As Jonathan Lis says:

The UK and EU are not speaking different languages, they are occupying different mental universes.

This, though, is egocentric framing ��� the inability to put yourself in the other guy���s shoes. I fear that in this case the error is magnified by our national self-delusions ��� our belief that we are an exceptional nation, for example that we are uniquely open to trade (despite the fact we export much less than the Germans) or that they need us more than we need them. (And of course, it's possible that the same error helps explain why ministers have not yet found a compromise among themselves).

It���s here that I lose patience. In a complex and unknowable world, it is impossible for us to optimize. Some ���errors��� of policy are therefore inevitable and forgivable. What we should expect of policy-makers, however, is that they avoid obvious mistakes, of which egocentric framing is one. The government, however, seems unable to do this.

July 5, 2018

Jobs, technical progress & productivity

Tim Worstall writes:

The aim, point, and process of economic advance is to kill jobs��� to get the task done with the use of less human labour���Economic advance is about using less labour to do any one task. This is why we obsess over productivity. It���s not so that we can gain more from the same amount of labour either. It���s so that some labour is freed up to go and do something else, which is the important matter.

This was true once, but it���s more questionable now.

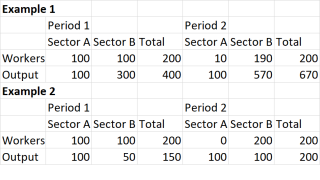

To see why, let���s take a simple example*. Imagine there are two sectors in the economy, each employing 100 people. Sector A produces 100 units (productivity is one) whilst sector B produces 300, so total output is 400. Now imagine that sector A sees technical progress so that those 100 units can now be produced by just ten workers. The other 90 go to work in sector B.

In this example, output rises to 670 units. That���s growth of 67.5%. And because those 90 workers are more productive in sector B than they were in sector A, their real wages are higher.

This demonstrates Tim���s point. Labour in sector A is freed to do something more productive. That���s progress.

This is not a contrived example. You can think of it as being a simple description of the shift from agriculture to industry in the 19th century west or in China more recently. Workers stopped working with spades and hoes as agriculture became mechanized and moved into factories where they worked with more machinery and so were more productive.

Let���s consider another example. Again, we start with 100 workers in sector A and 100 in sector B. The difference is that this time sector B is a low-productivity sector; it produces only 50 units. Now imagine that sector A becomes fully automated so its 100 workers must move into sector B. Total output now rises by only one-third. That���s half the rate of my first example. This is despite the fact that technical progress in sector A is faster in this case than in the first.

Note that I���m conceding a lot to Tim here, as I���m assuming full employment.

And here���s the thing. Just as my first example was reasonably realistic, so is the second. It���s consistent with a point Acemoglu and Restrepo make ��� that any incipient downward pressure on wages due to workers being displaced by technology can be offset by employers having an incentive to create low-productivity jobs.

You can think of the displaced workers in this example as being those in good manufacturing jobs who have to take less productive work in shops or call centres.

Alternatively, because trade and technology are essentially the same things (as David Ricardo pointed out) you can think of this example as a stylized description of the impact on US manufacturing of trade liberalization. Yes, the economy is bigger in period 2 than in period 1. But those workers who moved from sector A to sector B saw their productivity halve ��� and by extension their real wages. This illustrates Dani Rodrik���s point (pdf) ��� that even if globalization has net benefits, it can also have awkward local effects (pdf)**.

My point here is merely that technical progress and destroying jobs are not sufficient to achieve good economic growth, even where markets are functioning well. As Daniel Cohen says: ���if a worker���s individual productivity does not increase, growth is necessarily weak.���

* I���m borrowing here from Daniel Cohen, who in turn borrowed from Alfred Sauvy.

** My example overstates the actual effects of globalization, which has been only one of many causes of increased inequality (pdf).

July 2, 2018

Deluded centrists

The Labour right seem to think the financial crisis is irrelevant. This is the inference we might draw from Chris Leslie���s pamphlet, Centre Ground (pdf).

Pretty much the only reference he makes to the crisis is the claim that it ���fuelled cynicism about government and politicians���. Nowhere doe he even acknowledge the possibility that the crisis might undermine New Labour���s thinking about the relationship between the state and capitalism. The crisis ��� and the subsequent decade-long stagnation in real wages and productivity ��� shows for me that a stable policy framework is not sufficient for economic stability or growth; that economic growth might need greater state intervention than New Labour offered; that severe recessions can originate not merely from bad economic policy or macroeconomic shocks but from the failure (pdf) of key firms; and that the vast incomes and power of a tiny minority are not benign. In other words, social democrats need to rethink. The great virtue of Corbyn and McDonnell is that they see this.

Leslie, however, does not. Instead, he seems stuck in a 1990s mindset. This, for example, could have been said by Tony Blair in 1997:

It is the precipitous rate of technological development and globalisation that have churned the nature of employment and production, from what were rates of transformation that once occurred inter-generationally to now intra-generational change.

But this doesn���t seem to be true. Job-to-job flows are lower than they were before the crisis, suggesting that there���s less churn than there used to be. And of course stagnant productivity suggests the rate of technological development is much less than precipitous. The challenge for policy-makers is not to deal with the fall-out from economic dynamism, but to restart that dynamism.

This blindspot to the changed nature of capitalism is not an idiosyncrasy of Leslie���s. Only a few weeks ago Ian Austin complained that Corbyn has taken Labour out of the mainstream without even mentioning the crisis, and without even considering the possibility that a changed capitalism requires a changed Labour party.

Herein, though, lies a delightful irony. Although he���s oblivious to the nature of post-crisis capitalism, Leslie claims that the centre ground ���is grounded in the real world as it is today��� and is ���focusing on 21st century challenges ��� not 20th century nostalgia.��� One of the ���core values��� of centrism, he says, is ���evidence not ideology.���

The cognitive dissonance here is astounding.

What does this tell us? It might be corroboration of Karl Pahlman���s point, that politicians who claim to be evidence-based in fact have a ���hierarchy of knowledge��� and evidence that capitalism is dysfunctional comes well down this hierarchy. He writes (pdf):

Not all evidence in the policy process is equal���The types of evidence that are used and valued in the process represent important power dynamics in policymaking���Often, they support the dominant and prevailing ways of thinking about the world, rarely challenging the distribution of power.

I suspect, though, that there���s something else. Leslie is playing a common self-serving trick among centrists ��� of pretending that they are moderate, rational and evidence-based whilst their opponents (on both sides) are unreasonable ideologues. As Leslie says, centrists are ���choosing an evidence-based rather than ideologically-driven approach to the world.���

This, of course, is a fiction. What you believe and how you believe it are two different things. As I���ve said, extremism and fanaticism are distinct: you can be a fanatical centrist and (albeit less commonly I fear) a reasonable, sceptical extremist. Centrism is an ideology just like any other. Perhaps if centrists were to realize this they might acquire the self-awareness that is a necessary starting point for engaging intelligently with both Corbynism and capitalism.

June 28, 2018

Centrists against freedom

Manu Macron���s plan to reintroduce forced labour ��� which is what national service is - reminds us of an awkward fact - that many (some?) centrists are no friends of freedom.

We can read his proposal alongside some UK facts such as New Labour���s creation of thousands of new criminal offences and big increase in the prison population, the Lib Dems support for a sugar tax and minimum alcohol price, ���Blairite��� Caroline Flint���s recent call for ���an end to freedom of movement���, and the fact that Chris Leslie���s recent description (pdf) of six core values of centrism contained much more talk of responsibilities than of freedom.

Of course, this is not to say that all centrists hate freedom. They don���t. But it does show that there is an illiberal strand within many versions of centrism ��� more so than in my (not that idiosyncratic) conception of Marxism.

Why? Here���s a theory. One feature of centrism has long been a blindness to the less pleasant aspects of inequalities of power. Keynes, for example, thought the notion of class struggle to be a ���frightful muddle���, and his theory that full employment was a matter of technocratic macroeconomic management served to displace earlier ideas such as guild socialism and hence maintain hierarchical capitalism.

In a similar vein, centrist thinking ��� from New Labour���s forgotten Respect Action Plan (pdf) through the Taylor report to Leslie���s proposals ��� has tended to neglect ways of empowering ordinary people and workers, especially collectively. Sure, centrists sometimes want people to have more say as individuals ��� to be more like customers in public services. But generally, people are regarded as passive objects of policy, not active creators of it (except, perhaps when we must heed their ���legitimate concerns��� which are always about immigration and never anything else.) For centrists, politics is usually about what ���we��� can do for (or to!) ���them���.

There is of course a class aspect here. If you have the mindset of the ruling class, you will assume that power will be exercised wisely as long as the right people are in charge. Blair and Brown consistently fawned over bosses because they believed that leadership was generally benign.

From this perspective, centrists don���t worry about giving lots of power to governments, any more than they worry about bosses��� power over workers.

But they should.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers