Chris Dillow's Blog, page 38

October 2, 2018

Ideology for normal people

Jeff Sparrow accuses the left of being smug elitists who dismiss ordinary people as being dopes and fools. I don���t doubt that there is an element of superciliousness within the left. But there needn���t be. We can believe that people are misled by ideology into supporting the right without believing that they are stupid slack-jawed yokels.

Let���s start with behavioural finance. This is the idea that investors ��� including professional ones - fail to optimize because they are prone to many cognitive biases. This doesn���t mean they are idiots: even doctors (pdf) make similar mistakes. It just means none of us are Godlike Bayesians who always make the right decisions. Instead, we are ��� as the title of Meir Statman���s fine book says ��� just normal people. There���s a close analogy between some of the biases we see in behavioural finance and some we see in politics. This is why I can shift easily from writing about behavioural finance in the day job to writing about ideology in this blog: the two have much in common. For example:

- Anchoring. Kris-Stella Trump has shown that our perceptions of what is fair are anchored by actual distributions. This means that as inequality increased, so too did our perceptions of how much inequality is acceptable. But we also see anchoring in finance. Before the crisis, years of stability anchored bankers��� ideas of how risky their assets were, with the result that they took on too much risk and subsequent losses came as a shock (pdf) to them.

- Prospect theory. When people have lost, they tend to gamble in an effort to break even. I suspect this helps explain support for Trump and Brexit; people who felt that the country had lost out to globalization and to the elites were willing to gamble on risky prospects. We see a similar thing in financial markets. People hold onto badly performing shares in the hope they���ll come good. And they have traditionally paid too much for lottery-type stocks (pdf) such as Aim shares which offer the small chance of great returns.

- Under-reaction. People stick too strongly to their prior beliefs. In politics, this means too many people think the Tories are good custodians of the economy despite austerity, Brexit and Johnson���s ���fuck business��� remark. In finance, it gives us (or contributes to) the momentum effect ��� the tendency for assets which have done well recently to continue doing so.

- Wishful thinking and the optimism bias. These cause people to over-estimate their future incomes and to believe that austerity won���t affect them. It thus creates a bias against high taxes and welfare spending. Again, we see a similar thing in finance; investors over-estimate their ability to pick good stocks or funds.

These are not the egregious errors of idiots. Instead, they are ��� as Statman says ��� very often good shortcuts that sometimes lead us awry; we are often right to cleave to our priors, and a little wishful thinking is necessary to get us through the day. We are all prone to some of these mistakes sometimes. And if we commit them in finance where the incentives to think clearly are high, aren���t we more likely to commit them in politics where the incentives are weaker, non-existent or even perverse?

Now, I know that some of you are sceptical about the explanatory power of behavioural finance. Sometimes I suspect it is less of a positive project aimed at explaining the world than a normative one ��� a way of warning us against some common mistakes. Nevertheless, I suspect it does have some explanatory power. Insofar as this is the case, isn���t it also likely that the same mechanisms which cause poor investment decisions might also cause poor political ones? And both arise not necessarily from stupidity but from the fact that our cognitive resources are limited.

September 30, 2018

When detail matters

Chris Giles says that in predicting that a no-deal Brexit will cause house prices to fall 35%, Mark Carney���s has fallen ���into the trap of giving his audience precise numbers at a time they are neither knowable nor helpful.��� This poses the question: when is precision and detail useful, and when not?

In this case, Chris is right. A precise number gives the impression of knowledge which is in fact not available to us. I���d prefer that Carney���s warning was expressed as:

We have mechanisms which point to house prices falling because of Brexit: lower income expectations, plus heightened uncertainty (plus momentum effects after these have kicked in). These probably outweigh the positive effects upon house prices: increased optimism among Brexiters; and slightly lower interest rates. Although we can���t quantify how these mechanisms will play out, we can be moderately confident of the direction of change.

There���s another context when detail is unimportant ��� when we put it before general principles. Take, for example, McDonnell���s plan for increased worker ownership. The significant thing here ��� at this stage ��� is not the details, but the question: do the benefits of greater worker ownership outweigh the disbenefits of a slightly higher cost of capital caused by the dilution of owners��� current stakes?*

This is especially the case because the detail ��� at this stage ��� is malleable. The ��500pa cap on the amount of dividends workers can get, or the 10% ceiling on their stake, can both change in light of evidence.

In fact, there���s another reason why the details of MCDonnell���s plan aren���t very important. It���s that our uncertainty about the size and net direction of their behavioural effects surely swamps any quibble about those details. There is, as Thomas Meyer wrote, sometimes a trade-off between truth and precision in economics. Precise numbers can distract us from what���s really important, such as the confidence intervals around those numbers, and the costs of being wrong. In the run-up to the financial crisis, banks had precise estimates of value at risk which proved to be useless. They and us would have been better served by less precision and more truth. To take another, example, media demands that parties��� spending plans be ���fully costed��� ignore the fact that there���s massive uncertainty about future government borrowing.

Keynes didn���t actually say ���it is better to be roughly right than precisely wrong���, but he should have done.

This speaks to another context when precision is irrelevant ��� when it is mere noise. The FTSE 100 fell by precisely 35.24 points on Friday. For almost all practical purposes, however, this knowledge is useless. It tells us nothing worth knowing, and certainly nothing about what really matters for investors, which is where the market is heading. In fact, for the purposes of this question, almost all precise knowledge is useless ��� and in fact, worse than useless if relied upon for asset allocation.

So, when does detail matter? One is that it can be a guide to whether a policy is practical. McDonnell���s plan, whatever other demerits it might have, clears this hurdle. Brexiters��� plans for the Irish border, by contrast, don���t; they amount to little more than ���technology, yeah!���

Detail also matters, of course, when it cannot change ��� when we���ve signed contracts and treaties. It���s reasonable to demand more detail of those proposing a trade deal with the EU than of those proposing a change in tax rates: a trade deal is a bastard to change, a tax rate less so.

It also matters as a way of telling us whether somebody has thought seriously about a problem or not. The lack of detailed proposals for Brexit, for example, is as Chris Grey says, a sign that Brexiters just haven���t confronted basic realities.

Finally, of course, there is some truth in the old saw, ���the devil is in the detail.��� I suspect, for example, that the appropriate amount of worker say in the running of any business depends upon the detail of how knowledge, and about what, they have relative to management. This will differ from firm to firm, and cannot be known to policy-makers. Hayek���s great insight, of course, is that sometimes (often) important detail cannot be known by a single person.

Sometimes, then, detail matters and sometimes it doesn���t. I fear, though, that the media doesn���t sufficiently appreciate this. Precision makes better headlines: ���Carney warns of 35% slump in house prices��� is a better headline than ���Carney thinks house prices will probably fall by an unknowable amount.��� And interviewers sometimes prefer cheap gotcha quizzing about unimportant detail than about points of principle (at least when they are interviewing John McDonnell rather than Brexiters).

There are two useful things we should bear in mind here.

One is number sense. Sometimes, what matters is not a precise number, but questions such as: how confident can we be about that? Where does that number come from? Is it a lot or a little? The other is to be on guard against the illusion of knowledge. Detail and precision sometimes give us mere overconfidence, not genuine useful knowledge. We should ask: why does this matter? When we do, we can see that precision is only sometimes helpful.

* The policy is about corporate governance, not about giving a short-term boost to workers��� incomes ��� a point some have missed.

September 27, 2018

The neoliberal constraint

There���s something that troubles me about Labour���s otherwise admirable plan for greater worker ownership. It���s that it could fall victim to neoliberal* performativity.

What I mean is that there are two different ways to think about the plan. We could see it as a gentle step towards co-determination of a sort that���s common in Germany. Or we could instead see it as Sam Dumitriu does, as a ���straightforward hike in taxes on profits��� ��� perhaps even as a form of expropriation - which will raise the cost of capital and so reduce investment.

This is where performativity comes in. Words are not mere words. How you describe the scheme determines its effects. The boss who regards it as a mild reform is likely to try to make it work. The one who regards it as a threat to property rights and to his empire is more likely to up sticks. If Sam���s view is widely shared in boardrooms, his warning that firms will disinvest will be self-fulfilling.

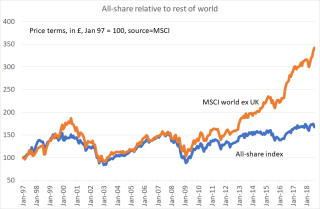

Now, in mere hydraulic terms, Sam���s warning seems overblown. One Big Fact tells us this. UK share prices have under-performed the rest of the world for ten years, suggesting that the UK���s cost of equity capital has risen relative to that elsewhere. AFAIK, however, critics of McDonnell have been relaxed about this ��� and perhaps rightly so, as it���s difficult to establish that this has deterred investment and innovation**.

Hydraulics, however, are not the point. What matters is animal spirits. A rise in the cost of capital because of direct policy action might have worse effects upon investment than one caused by stock market falls for other reasons ��� especially to the extent that a Corbyn government will increase uncertainty anyway.

What I���m trying to drive at here is that neoliberalism doesn���t just describe the world, but shapes it. As Jesse Norman says, ���markets are living institutions embedded in specific cultures���. Our culture is a neoliberal one, which affects how markets operate. For example:

- Tax. If you regard higher tax as a price worth paying to live in a civilized society, you���ll be content to pay (moderately) higher rates. If, on the other hand, you regard it as theft then you are more likely to take steps to avoid it, either by working less, or migrating or dodging it by legal or illegal means. The shape of the Laffer curve depends upon tax morale and ideology. Neoliberal beliefs cause the revenue-maximizing top tax rate to be lower than it would be with social-democratic beliefs.

- Regulation. If bosses feel constrained to act with a sense of propriety in accordance with public morality ��� as Adam Smith thought we were ��� then they are likely to abide with new regulations. If, on the other hand, they regard them as restraints on the right to manage, they���ll seek to game them or avoid them.

- Politics. If you regard politics as just another marketplace in which the customer is king, you���ll defer to public opinion and thus downgrade expertise and representative government.

These are all ways in which neoliberal beliefs can be self-fulfilling. But they can also be self-refuting. For example, in the early 00s mainstream economists thought that securitization was a good way of pooling risks and thus of increasing financial stability. This emboldened banks to gear up, thereby causing a crisis.

My point here is a disquieting one. It is the case that many neoliberal ideas are plain wrong; neoliberalism, for example, might well have retarded productivity growth. It is not, however, sufficient to point this out. Neoliberal ideology ��� whether right or wrong ��� can create its own reality. Insofar as this is the case, it is a constraint upon what social democratic governments can achieve.

* Yes, I know some of you hate this word. But I can���t think of a better one in this context.

** Though of course, ascertaining cause and effect is damnably hard: is the All-share���s under-performance a cause of lacklustre growth, or the result of expectations of it?

September 26, 2018

A Crisis of Beliefs: a review

Whilst I was away, there was a debate on Twitter about why so many Oxford PPEists become newspaper opinion writers. The question was ill-posed: in fact only a teeny fraction of PPE graduates enter that profession - much less than 1%.

The idea that PPEists become opinion-mongers is an example of the representativeness heuristic - our tendency to over-estimate a probability if something seems representative of a group. In this case, because bashing out half-cocked opinions quickly seems representative of PPEists, people over-estimate the probability of PPEists becoming opinion-writers. In doing so, they neglect base rate probabilities: there are thousands of us PPEists but only a few opinion-writers.

For years, doctors have made this same mistake. Back in 1982 David Eddy showed that they over-estimated (pdf) the chances of patients having a disease if they had tested positive for it: because a positive test is representative of the disease, they neglected the basal probability of the disease. In Bayesian terms, people mistake P(A|B) and P(B|A): we all do.

The same mistake explains the financial crisis of 2008, according to a new book, A Crisis of Beliefs, by Nicola Gennaioli and Andrei Shleifer. They argue that the market stability of the 90s and early 00s caused investors to over-estimate the probability of stability continuing ��� stability being representative of a healthy financial system.

In other words, they say, investors have neither the na��ve adaptive expectations attributed to them by early Keynesians, nor fully rational ones. Instead, they update their beliefs in light of new evidence (such as prolonged stability) but do so in a quasi-rational way, to use Richard Thaler���s phrase.

This theory fits a Big Fact ��� that the crisis was not a bolt from the blue. In a neat narrative of the events, Gennaioli and Shleifer show that the crisis was bubbling up for months before Lehmans collapsed: US house prices began falling in 2006 and some sub-prime lenders and hedge funds holding mortgage-backed securities collapsed in 2007. Such events did not trouble equity investors much, however, because they took past stability to be representative of future stability and so thought that the risks posed by the housing market were manageable. It was only when Lehmans collapsed and was not bailed out that this belief changed. And ��� in retrospect ��� investors over-reacted to that collapse because of the same representativeness heuristic: a banking crisis is representative of a dysfunctional economy, which led to shares falling too far.

Personally, I like this explanation, but with four caveats.

One is that it is not a full explanation of the crisis. Gennaioli and Shleifer do not ask why demand for ���safe��� assets was so high in the mid-00s. The deeper structural failings of capitalism that created that demand are outside the purview of their book.

Secondly, they fit this theory to only the 2007-08 crisis without applying it to others. This invites the old criticism that economists see something fail in practice and wonder if it can fail in theory.

I suspect, however, that it does have wider applicability. It might fit the tech bubble: sharply rising share prices are representative of great future businesses, thereby leading people to over-estimate the likelihood of companies becoming the latter. It might also be consistent with economists��� longstanding failure to foresee recessions: growth is representative of normal stable economies, which leads us to under-estimate the chance of downturns.

Thirdly, they pay insufficient attention to the question: why doesn���t the smart money correct this inferential error? The answer, in fact, lies in one of Shleifer���s earlier papers ��� that there are tight limits on how far one can short-sell; if you���re right at the wrong time, margin calls can wipe you out. There���s a reason why John Paulson and Michael Burry were rarities in profiting from the slump in mortgage securities.

Finally, I fear they underplay mechanisms which reinforce inferential errors. For me, one of the most revealing statements of the crisis was that of Chuck Prince, then head of Citigroup, in July 2007:

When the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will be complicated. But as long as the music is playing, you���ve got to get up and dance. We���re still dancing.

This speaks to institutional and psychological pressures. The cautious manager who avoided sub-prime mortgages or shorted them under-performed his peers in the mid-00s and so faced calls from investors to change strategy; that scene in the Big Short where big investors demand their money back because being early is the same as being wrong rings true. And even without such demands, it���s hard to disagree with the herd; as a great philosopher said, you must be strong if you���re to go it alone. Again, though, Shleifer���s own work speaks to this: his paper Chasing Noise describes the herding mechanism well.

You might think all this is minor stuff. It���s not. Although the representative heuristic seems like a small deviation from rationality, it has a devastating effect. Gennaioli and Shleifer say:

We expect new financial products to load up precisely on the risks investors do not fully appreciate. Under rational expectations, financial innovation would improve risk-sharing and welfare. With neglected risk, in contrast, it creates inefficient risk-sharing and the possibility of crises. (p87)

In this sense, the psychological question of how expectations are formed raises a much more general question about the stability of the financial system. It is, therefore, a deeply political question.

September 25, 2018

Worker ownership: threat or promise?

Labour���s plan to force large companies to give workers a 10% stake in them seems popular: Yougov reports that most voters and even a plurality of Tory supporters think it a good idea. On the other hand, though, it���s given the CBI a fit of the vapours. Carolyn Fairbairn says:

Their diktat on employee share ownership will only encourage investors to pack their bags and will harm those who can least afford it. If investment falls, so does productivity and pay.

She���s wrong, and the voters are right. Far from being anti-business, McDonnell���s plan might even be a way of shoring up capitalism. I say so for four reasons.

One is simply incentives; giving workers an ownership stake incentivizes them to work better. There���s a large body of evidence (pdf) which shows that worker ownership increases productivity. If it���s a good idea to give CEOs an equity stake in the business ��� so that their incentives are aligned with shareholders ��� why should it be a bad idea to give workers such a stake too?

Secondly, giving workers ownership gives them a voice: as Tom says, a 10% stake would make workers the single biggest owner of many listed companies. And this voice is worth hearing. There is, as Kenneth Boulding warned, always a danger that managers of large organizations ���will be operating in purely imaginary worlds.��� Worker voice can be a valuable corrective to this by bringing ground truth to CEOs��� attention: workers on the ground are sometimes the first to spot deteriorations in cash flow or product quality. And it���s easier to nip problems in the bud than solve big ones. This is therefore a step towards what Shann Turnbull calls network governance and cybernetic control.

The third mechanism operates at the political level. If workers have substantive stakes in their businesses, they will support more business-friendly policies, just as Thatcher���s right-to-buy policy created a constituency in favour of high house prices. That should increase support for productivity-enhancing policies, and decrease support for higher taxes on business.

Fourthly, worker ownership brings into play new methods of stabilizing output. Roger Farmer has proposed that the Bank of England acts to stabilize animal spirits by using a form of QE to directly raise share prices in a slump. Right now, this is ruled out on the grounds that it would increase inequality. If, however, shares are more widely held, this objection disappears.

All this raises two questions.

One is: if a worker stake is such a good idea, why is the CBI so opposed to it?

There is, in fairness, a minuscule element of validity behind Fairbairn���s hyper-ventilating. Giving workers a 1% stake each year would dilute the stake of current owners. That should slightly depress share prices; it���s a form of mini-rights issue. This matters, because there is growing evidence that weaker stock markets lead to both lower productivity growth and higher unemployment (pdf). Animal spirits matter. It is no longer the case that we can dismiss stock market fluctuations as Paul Samuelson did, on the grounds that they���ve predicted nine of the last five recessions.

Also, though, there���s a framing effect. McDonnell and many of his supporters are framing his proposals not as a means of helping capitalism, but as a radical, transformative plan. In their current form, however, they could equally be seen as a move to a shareholder democracy ��� the sort of thing Thatcher wanted but didn���t deliver*.

I suspect, however, that there���s an even less reputable reason for opposition. It���s simply that bosses��� sense of self-regard and entitlement has grown so huge that they resent even moderate counterbalances to their power. This might help explain why many Tory voters support McDonnell���s plan; small shareholders are sick of being ripped off by CEOs greed and incompetence and welcome any curbs upon these.

Which raises the second question: mightn���t these plans be just too mild? Is a 10% stake sufficient to create a feeling of ownership? Are ��500 a year of dividends sufficient incentive to boost productivity? As Tom and Jon point out, these are mild social democratic plans, which might arguably give workers less power over firms than they currently have in Germany.

What���s going on here, I suspect, is that McDonnell is laying down some stepping stones. A 10% stake isn���t the end of things. If it proves mildly successful ��� as it might well ��� it���ll lead to demands for bigger stakes and a bigger worker say. And let���s face it, the case for worker-shareholders is in some ways** stronger than that for outside shareholders: it���s long been known (and was proven by the collapse of banks in 2007-08) that these are incapable of overseeing management properly.

In this sense, McDonnell���s plan would call into question the very nature of capitalism. Which means that what capitalists have to fear is not that it would fail, but that it would succeed.

* The proportion of UK shares held directly by individuals has fallen from 37.5% in 1975 to 12.3% now.

** The counter-argument here is one of risk-pooling: worker-owners put all their eggs into the basket of one firm, whereas outside shareholdings are a way of spreading risk.

September 12, 2018

Radical Markets: a review

In recent years the case for free markets has become tainted by association with a defence of the rich ��� an association which free market think-tanks have done too little to disentangle. It was not always so, however. Adam Smith and David Ricardo (and Thomas Carlyle!) saw free markets as an attack on privilege. Posner and Weyl���s Radical Markets is an attempt to return to that older tradition of Philosophical Radicalism. They want to use markets to equalize wealth.

One of their main ideas is what they call COST ��� a common ownership self-assessed tax. The idea here is that we assess the value of all our possessions and pay an annual tax on that value ��� the snag being that everybody can see our assessments and force us to sell our property to them at that assessed price. This gives us an incentive to assess our wealth properly ��� if we over-estimate it we pay too much tax and if we under-estimate it we risk losing our possessions with insufficient compensation. In effect, then, all property becomes commonly owned and we rent it from others ��� the rent being the tax we pay. You can think of this as a back-dated consumption tax.

Posner and Weyl see the obvious objections to this, and deal with them well. I was almost convinced.

But only almost. For me, it fails the Cushnie principle: is it worth the bother? Ryan Aven rightly says that self-assessment would impose a massive cognitive load onto all of us. And for what? I���m not sure why a COST is much better than a wealth or land value tax accompanied by their incentive-enhancing self-assessment mechanism,

Another of their ideas is quadratic voting; in effect, people are given a budget of ���voice credits��� each year and can allocate more of them onto issues where they feel strongly. I sympathize with this - I���ve supported something similar myself ��� not least because it might, in the long-run, improve the quality of debate by reducing hyperbole: any blowhard trying to exaggerate an issue can be countered with the question: ���how many votes will you spend on it?���

But, but, but. I���m not sure this tackles the big failures of our democracy: the fact that the rich have too much influence; the fact that the standard of public discourse is piss-poor; and the fact that some issues get onto the agenda whilst others, sometimes more deserving, do not.

Yet another of their ideas is that data is labour ��� that we should be paid for the data we provide for free to the internet giants. This is better. What they hint at ��� but don���t quite say explicitly ��� is that this is a challenge to neoclassical economics. For any individual, the marginal product of our data is negligible. Collectively, however, it is huge. What does this tell us about marginal productivity theory?

I these senses I agree with Diane and with Ryan. Whilst their actual proposals are dubious ("barking mad" is Diane's phrase), their philosophy deserves careful thought, as they are asking good questions about the relationships between property rights and markets.

I feel Posner and Weyl are on stronger ground when they advocate limits on institutional investors��� ability to hold shares in companies in the same industry. At the moment, they say, cross-holdings deter firms from competing against each other. This is good. But it���s an extension of anti-trust powers, not a radical market.

What���s more, there are some odd omissions. For me, a better way of using markets to help ordinary people was proposed years ago by Robert Shiller: we should, in theory, have markets that allow us to insure against recessions, falling house prices or declining wages. Posner and Weyl, however, don���t mention this.

And in fact, 26 years after Shiller proposed them, we still don���t have them. Which raises a challenge to Posner and Weyl: why do our imperfect actually-existing markets work in favour of the rich so much? Might it be that they have captured the economy (to use Lindsey and Teles��� phrase) not because of a lack of intellectual energy by those who want proper markets, but because they have the power? (The issue here is one raised by Dani Rodrik, about the weight of ideas versus interests.) If this is the case, then a free market economy requires an attack upon that power. Free marketers such as Posner and Weyl must then answer the question in that old folk song: which side are you on?

September 11, 2018

The BBC's bias against understanding

Over the weekend, the two main political stories on the BBC were Chuka Umunna���s row with the Labour leadership and Boris Johnson���s attack upon Theresa May, whilst John McDonnell���s plan to gradually end capitalism was ignored*. Then yesterday John Humphrys prefaced a question about the type of Brexit Leavers want with the words that this is ���all getting a wee bit technical and I���m sure people are fed up to the back teeth of all this talk of stuff most of us don���t clearly understand��� (2���12��� in).

All this (and you can no doubt think of more or better examples) is a symptom of a BBC bias ��� a preferences for reporting splits and divisions rather than detailed analysis of policy. This has nasty effects.

One is that, as Nick says, it creates a bias against understanding. The question: ���what type of Brexit do you want?��� is a vitally important one. The fact that one of the BBC���s best-paid journalists can dismiss it as ���stuff most of us don���t clearly understand" is therefore an admission of colossal failure. Polls show that the public are wrong about many basic social facts. Our biggest broadcaster must surely take some responsibility for this.

Secondly, it generates a bias towards charlatans. Because the BBC doesn���t do policy detail, empty windbags who don���t have such policies get a free pass. Brexiters who don���t have a plan for leaving have gotten far more coverage and deference than they merit. This bias perhaps plays against the Tories as well as Labour. The fact that clowns like Johnson** get more coverage than the likes of Rory Stewart, Robert Halfon, David Willetts or Jesse Norman surely puts the Tory party into a much worse light among thinking people than it would get from a reputable broadcaster.

By the same token, MPs who cultivate links with journalists (and share their posh backgrounds?) get better coverage than those with, say, technocratic backgrounds or links to trades unions. I suspect that one reason why the BBC has been so bad at covering Corbyn (especially soon after his election as Labour leader) is that it has been blindsided by the fact that he has much more support outside Westminster than in.

Thirdly, if politics is presented as a fight for position it encourages a na��ve cynicism ��� the idea that, as Jonathan Calder says, politicians are ���all alike and all in it for themselves.���

The other side of this coin is perhaps even nastier. It encourages people to believe that politics is not about them but is instead a cosy game for posh people. That breeds at best apathy and at worst populism. And this effaces a deep truth ��� that politics is in fact literally a matter of life and death for the poor and voiceless.

To see my point more clearly, imagine that the BBC did not cover gossip, jockeying for power and idle disagreement but instead focused solely upon policy. Wouldn���t we have a better type of politics?

Now, some of you might reply that splits and divisions are news and that policy proposals are not. This won���t do. ���News��� isn���t something natural and given. It is defined by convention. My gripe is that this convention isn���t neutral, and has social consequences.

Alternatively, you might say that divisions are indeed important as they signal whether a party is competent to govern. Maybe they do, but in the exact opposite way you and the BBC think. It is party unity that is dangerous. Some of the worst policies of our time ��� the poll tax, austerity and (to a lesser extent as there was some opposition to it) the Iraq war ��� were undertaken by strong leaders of united parties. The Workers Party of Korea is united, but few of us consider North Korea well governed. Disagreements, if conducted intelligently, are a sign of a healthy lack of deference and groupthink.

There is, though, another objection to what I���m saying ��� that the public actually want gossip rather than detailed policy analysis. This might well be the case. Whether a public service broadcaster should pander to such tastes is, however, another matter. We would not tolerate an industry that massively pollutes the environment. So why should we tolerate one that pollutes public discourse?

* The Today programme did cover it this morning, but the news report presented it as a marketing strategy and Martha Kearney���s interview with McDonnell ��� whilst giving him a word edgeways ��� was perfunctory and she was clearly keen to get away from economics to the more comfortable territory of splits and divisions.

** The mere fact that journalists call him Boris in a way they don���t use first names for (say) Theresa May or Jeremy Corbyn is itself revealing.

September 9, 2018

Talking 'bout my generation

Lord Blunkett made an interesting point on Friday���s Today programme (2���18��� in):

Nobody below their mid-50s will remember the early 1980s���The problem for the group who think it would be possible to create a new [centre] party is that they have forgotten or didn���t know about what happened to the SDP [that it fragmented the opposition and so gave the Tories a huge majority].

What he���s driving at here is that our beliefs are shaped not merely by facts but by the direct memories of our formative years. If you were politically aware in in your teens and early 20s in the mid-80s, you���ll have vivid memories of how the SDP did indeed weaken Labour*, and how early hopes for the party were dashed. Amongst 50-somethings, these memories create a jaundiced view of new centre parties ��� a view perhaps not shared by those younger than us.

This reminds me of two papers by Ulrike Malmendier and Stefan Nagel (pdf) and by Henrik Cronqvist and colleagues. They show that people who spent their formative years in recessions hold fewer shares, but more value stocks, even years later than people shaped by good economic times. Lord Blunkett is saying that their point generalizes to political attitudes. I suspect he���s right. Here are some other examples:

- Young activists such as Ash Sarker and Aaron Bastani boast of being communists. People of my generation with similar opinions, however, would avoid that word as for us it is tainted by association with Stalinism. Those whose formative years were spent after the collapse of Communism have no such inhibitions, however.

- People in their 20s have spent their formative years living with the financial crisis and its aftermath. They are therefore more likely to be sceptical of capitalism than those in their 30s and 40s, whose formative years were spent in times of stable growth. It should, therefore, be no surprise that they are disproportionately supportive of Corbyn ��� and that those of us shaped by the recession of the early 80s should be sympathetic to them.

- Those of us who remember the strikes of the 70s and 80s know that class struggle matters. For those slightly younger than us, however, class is less salient ��� though even younger people are relearning its importance.

- For people whose formative years include 2003, the Iraq war made a big impression; it is these, I sense, who are most hostile to Blair. For the rest of us, the war was just another policy error.

- My ideas were disproportionately shaped by the inflation and mass unemployment of the 70s and 80s. These taught me that economics matters; it���s not merely a way for second-rate mathematicians to fool themselves that they are clever. People who enjoyed economic stability in their formative years, however, might think economics less important.

The psychology here is simple. There is such as a thing as an impressionable age ��� in this context, our teens and early 20s. I, for example, have vivid memories of most of what happened between around 1976 and 1989, but everything before then is what I���ve only read or heard about, and everything since is a bit of a blur, mostly of minor significance.

Hume was more or less right. We have impressions ��� things which enter our mind with ���most force and violence��� ��� and ideas, which are ���faint images���. Our experiences in our formative years are impressions; everything else is an idea. This, I suspect, lies behind at least some of the generational divide in politics. And its partisans are insufficiently aware of it.

* I suspect that for some centrists today, the risk of letting the Tories win is one they are happy to take.

September 8, 2018

Doubts about wage-led growth

���Higher wages prompt improvements in productivity���. This is one of the central claims in the IPPR���s report this week. But I wonder: how true is it?

Certainly, it can be for individual firms. An employer who pays better than the going rate will attract better workers, motivate them more, and enjoy lower staff turnover. Not everybody, however, can pay better than average. What���s true for one firm, therefore, need not be true of all.

Instead, there are two other mechanisms whereby higher aggregate wages might raise overall productivity.

One is that a shift in the distribution of income from profits to wages might increase aggregate demand and ��� via Verdoorn���s law ��� this would boost productivity. This would happen if the marginal propensity to consume out of wages is higher than that to consume and invest out of profits.

Personally, I���m sceptical of this. Without other changes, pay rises for the low-paid would be partially offset by lower tax credits and might be used to pay off debts rather than for consumption. Also, many low-wage employers are not high-rollers squirrelling profits overseas but instead, spend a high proportion of their incomes, either on capital or consumption goods.

Which brings a second mechanism into play. If fiscal policy maintains proper full employment, the prospect of continued high wages and strong demand might induce firms to invest and innovate more, thus raising productivity.

The question here, then, is: can we have wage-led growth, whereby higher wages trigger growth and productivity improvements? Or do we need profit-led growth, in which firms are induced to invest by high profit margins? A famous paper (pdf) by Steven Marglin and Amit Bhaduri showed that both are possible in theory: see too papers by Marc Lavoie (pdf) and Engelbert Stockhammer (pdf).

Empirical evidence here is mixed. One the one hand, we got wage-led growth in the 50s and 60s, when labour shortages and rising wages encouraged firms to raise productivity. And ��zlem Onaran and Giorgos Galanis have shown (pdf) that in recent years a lower wage share has been accompanied by weak aggregate demand in many countries.

On the other hand, though, a study of investment in the 70s and 80s by Robert Boyer and Sam Bowles found that the chances of wage increases fuelling faster investment are ���extraordinarily small���*. The profit squeeze of the 70s led to weak capital spending and lower aggregate growth. And Robert Allen has argued (pdf) that low wages and a high profit share were crucial in stimulating investment and innovation in the early phase of the industrial revolution.

There���s a reason why the empirical evidence is so mixed. So much depends upon the nature of capitalists��� animal spirits. They could react to full employment, high wages and an incipient profit squeeze by thinking ���demand will stay high and we need to cut labour costs, so let���s invest in labour-saving technologies.��� Or they might figure: ���this boom is unsustainable, and the government might further restrict our property rights, so let���s not invest.��� Both reactions are possible.

Here, two things make me pessimistic. One is that the Bank of England thinks the Nairu is high; it raised Bank rate last month even though unemployment was almost 3.5 million**. This makes genuine full employment impossible; it���ll be countermanded by tight monetary policy.

This barrier can be overcome by changing the Bank���s mandate. (Personally, I suspect a money GDP target or higher inflation target would be better than a dual mandate, but that���s another matter.)

Another barrier, though, might be more intractable. It���s that neoliberalism is partly performative. For decades, the dominant ideology has been that economic growth requires a quiescent labour force. As a factual claim, this is wrong. But if firms believe it, they���ll respond to the sort of policies advocated by the IPPR by reducing investment. To this extent neoliberalism might be self-fulfilling. And even if this is not the case, a government implementing a meaningful shift towards social democracy would be seen as radical, which in itself might create uncertainty ��� and uncertainty, we know, often tends to depress capital spending.

Why, given these reservations, do I welcome the IPPR report so much?

One reason is that it is obvious to everybody except the 1% and their shills and lackies that capitalism is failing in its current form. Equally, though, capitalism has served us reasonably well for decades. It therefore deserves the chance of reform, which is what the IPPR offers. And I might be wrong***.

But what if I���m right? It doesn���t necessarily follow that the neoliberal status quo is right. We could equally well draw a Marxian inference instead ��� that capitalism is spent and no longer compatible with acceptable living standards for working people and that we need more radical measures than the IPPR is proposing ��� among them that the task of investment can no longer be entrusted to capitalists. Perhaps, as the man said, ���a somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment will prove the only means of securing an approximation to full employment.��� (That man was Keynes.)

* In Epstein and Gintis���s superb Macroeconomic Policy after the Conservative Era.

** 1.4m officially unemployed and two million out of the labour force who want a job.

*** These words are rarely heard, but they should be a central part of all policy-making and debate.

September 6, 2018

Short-termism: what's the problem?

There���s a widespread consensus that corporate short-termism is a problem. Many have welcomed Donald Trump���s call to end quarterly reporting in the hope that it might lengthen planning horizons; yesterday���s report from the IPPR cited short-termism as one reason for the UK���s lack of investment and innovation; and Richard Murphy has decried the ���transient enterprise.���

I disagree with all this. I side instead with Sam Dumitriu and Larry Summers: short-termism is not a problem. Four facts make me say so:

- If stock market investors were short-termist, they���d under-price growth stocks and over-price those offering near-term cashflows. In fact, more often than not they���ve done the opposite. Growth stocks have under-performed value ones in the UK over the last 30 years*. That suggests investors have been too long-termist.

- The profits to innovative activity have been low: William Nordhaus estimates that firms have captured only a ���minuscule fraction��� of the overall benefits of innovation**. This suggests that low innovation might be due to a realistic assessment of its pay-offs rather than to irrational short-termism.

- Suresh Nallareddy and colleagues show (pdf) that the introduction of quarterly reporting in the UK had ���virtually no effect on investment decisions, as proxied by capital expenditure; levels of plant, property, and equipment; R&D, and intangible assets���.

- Charles Lee and Salman Arif show that when firms do increase capital spending, it leads to lower GDP growth and more corporate earnings disappointments. This suggests that low capital spending is rational.

In fact, it might be that a reason for low innovation and investment is not that companies are too short-termist but that they are too long-termist. A good reason not to invest is the fear that profits will be bid away by future, cheaper, technologies. Uncertainty is much greater about the long-term than the short-term: firms can know who their rivals are today, but have no idea who they���ll be in (say) ten years��� time. And uncertainty is a reason not to invest. This is especially the case if Rosewell and Ormerod are right, and that companies have no idea about the future.

Plenty of firms are niche businesses, filling a gap in the market. But niches can exist in time as well as space. Profits are not persistent. Corporate death rates are high. This isn���t simply because many are badly managed (though they are (pdf)). It���s also for a reason pointed out by Peter Rousseau and Boyan Jovanovic. Firms, they say, embody specific vintages of organizational capital ��� the best practices and technologies at the time they were founded. Sometimes, though, better vintages come along, so firms must adapt or die. Adaptation, though.is difficult***; you can���t teach an old dog new tricks, as Gooners watching Petr Cech this season know. Rational bosses, knowing this, might be loath to expand.

What looks like short-termism might therefore be a reasonable response to the reality of creative destruction ��� something which is a central feature of a healthy, competitive economy.

None of this is to deny that bosses have plundered ailing companies such as Carillion and BHS. The problem in these cases, however, is not their irrationality but their excessive power.

Now, many people might interpret this denial of short-termism as a problem as a defence of capitalism. It���s not. Quite the opposite. We could just as well draw exactly the opposite inference: maybe low investment and innovation are deep-rooted features of modern capitalism which are not so easily eliminated by tweaks to corporate governance.

* By 1.8 percentage points per year in total returns, if we compare the FTSE 250 high yield and low yield indices.

** Apple is an obvious exception to this. This is because Steve Jobs genius was not so much as an innovator as in being a creator of brand power.

*** Ironically, Whitbread ��� the firm cited by Richard ��� is an exception to this.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers