Chris Dillow's Blog, page 35

January 8, 2019

The death of right libertarianism

Right libertarianism is dead. It has ceased to be. It has expired and gone to meet its maker. It has joined the choir invisible. That is the inference to draw from John Redwood���s recent claim that Brexit is a ���huge opportunity to���grow more of our food���, prompting Jonathan Portes to note that the man has gone from ���economic liberalism in its purist form��� to rebooting The Good Life. As Jonathan Calder says, the Tories are staging a headlong retreat from the free market.

This is not an isolated instance. Just before Christmas Norman Lamb���s proposal to legalize cannabis was opposed by prominent Brexiters such as Rees Mogg, Bridgen and Cash. Support for more liberal immigration policy is more likely to be found on the left than on the right. And the #MeToo movement ��� which is essentially an assertion of the libertarian ideal of self-ownership ��� has at best only tepid support from the right.

All these cases show that the right is not libertarian. Lefties love to ask the IEA and TPA ���who funds you?��� Doing so, however, misses the key point ��� that such thinktanks have to rely upon a small cabal of cranks and oligarchs* because their causes lack widespread support.

Now, this is not to deny that there are a few sincere libertarians out there such as Christopher Snowdon or Sam Bowman. But for every one of these there are, I suspect, many more shills for the rich, crypto-currency cranks, IQ fetishists or mindless contrarians. Right-libertarianism is no longer a serious political or intellectual force in the UK**.

Why? It has always been the case that libertarianism is unpopular with the public. Even when they were voting for Thatcher, less than 10% of voters wanted to cut taxes and reduce spending on health, education and welfare***. This might have been because, as Hayek said, the benefits of freedom are diffuse and unpredictable:

Since the value of freedom rests on the opportunities it provides for unforeseeable and unpredictable actions, we will rarely know what we lose through a particular restriction of freedom. Any such restriction, any coercion other than the enforcement of general rules, will aim at the achievement of some foreseeable particular result, but what is prevented by it will usually not be known....And so, when we decide each issue solely on what appear to be its individual merits, we always over-estimate the advantages of central direction. (Law Legislation and Liberty Vol I, p56-57)

Back then, though, there were men like Redwood who were economic liberals.

So what changed?

It could be that such claims to love freedom were insincere. Many on the right only used freedom as a stick with which to beat the Soviet Union: many were quiet about the crimes of Pinochet or apartheid South Africa, and they remain content with workplace coercion.

But there���s something else. It���s that one of the foundational beliefs of small-staters has been refuted by events. The idea that capitalism could thrive with only minimal state intervention was disproved the moment the government bailed out the banks in 2008.

That was a specific instance of a more general pattern. In his famous AEA presidential address (pdf) in 1968 Milton Friedman said:

Our economic system will work best when producers and consumers, employers and employees, can proceed with full confidence that the average level of prices will behave in a known way in the future.

This, he thought, would create a climate ���favourable to the effective operation of those basic forces of enterprise, ingenuity, invention, hard work, and thrift that are the true springs of economic growth.���

Events have proved him wrong. Since the 1990s inflation has been stable. As Eric says, it ���is truly dead, and policy makers don���t need to worry about it.��� And yet the ���basic forces of enterprise��� have been weaker now: productivity has stagnated for years. The idea that governments only needed to provide price stability and low but stable regulation to unleash a dynamic economy has been proven wrong. The state must be more active than that. In this sense, the demise of right libertarianism is an example of evidence-based policy.

Perhaps, then, we should regard Brexit as a displacement activity: having realized that a small state is unachievable, rightists directed their energies elsewhere.

* Maybe they���d be not: I���d be happy to be proven wrong.

** No, support for the Singapore model does NOT make you a libertarian.

*** This isn���t as contradictory as it seems: Thatcher was not the small-stater of latter-day myth.

January 2, 2019

Brexit: in defence of Corbyn

Labour���s ambivalence towards Brexit is coming under attack from good people. Simon Wren-Lewis says it would be an ���historic error��� for Labour to enable Brexit, and Chris Bertram says Brexit could be ���the end of Labour���. I fear such criticisms are too harsh.

Granted, they do have a point. Most Labour voters, and the vast majority of the party���s members are Remainers. Tom Kibasi is thus right to say that Corbyn should worry more about alienating these than the small minority of Labour Leavers.

This, however, is not the only consideration. Brexit is of course a toxic and deeply divisive issue. In keeping a low profile, Corbyn has so far been able to minimize these divisions within Labour whilst allowing the Tories to implode. Barry Gardiner might have been imprudent to tweet Napoleon���s maxim, ���never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake���, but the sentiment was sound. It's a good idea to keep away from the live rail.

More importantly, I fear that Corbyn���s critics are are insufficiently sympathetic to the philosophical dilemma that Labour faces. On the one hand, Brexit is a stupid idea: escaping weak constraints upon state intervention in the economy is too small a gain to offset the cost of leaving the single market. But on the other, there is a clear mandate for it. As Phil says, seeing Brexit through is ���the democratic thing to do.���

This dilemma has little force for technocrats who think voters are Putin���s dupes or for paternalistic centrists. But it is a problem for the left. A big part of our philosophy is the desire to give working people greater voice in work and in public services. It���s difficult to say people should have more voice in boardrooms whilst denying that voice in a referendum*.

It is this dilemma, perhaps more so than electoral considerations, that justifies Labour���s ambivalence towards Brexit. What we need from Corbyn, then, is a way of retreating from Brexit whilst being able to show that there is a democratic mandate for doing so.

From this perspective, I suspect Paul is right to interpret Corbyn���s now-notorious Guardian interview as a tactical gambit. His claim that he could negotiate a less-bad deal with the EU is necessary if Labour is to demand a vote of no confidence in the government; an opposition can only demand the fall of the government if it can claim to do a better job.

I don���t think such a claim means that a Corbyn government would take us out of the EU without a second* referendum. The fact that most Labour members want one ��� and that Conference asked for the option to be kept open ��� must weigh heavily with the Labour leadership.

But as Paul says, timing is important. Demanding an early referendum would risk a no-deal Brexit, as this would be on the ballot paper if May set the referendum question whereas it probably wouldn���t be under a Labour government. Also, such demands could be presented as a way of thwarting ���the will of the people.���

It would be better to call for such a referendum as a last resort. Under a Tory government, Labour should claim that as parliament and the government are unable to resolve the matter it should be put again to the people. And under a Labour government, the party should say: ���this is the best deal we can do: do you want this or to remain?���*** Either approach has a chance of overcoming that fundamental dilemma, of how to reconcile staying in the EU with respecting the voice of the majority.

Now, I say all this cautiously: disagreeing with Simon and Chris usually means one is wrong. If, somehow, Corbyn were to take us out of the EU without a vote, he would lose my support ��� and I'd be in a big crowd.

I suspect, though, that we agree upon the principle. Brexit is a big heap of Tory shit. The question is one of tactics: how to get rid of it whilst minimizing the damage to the Labour party which offers our only hope of decent government.

* Not impossible, because the conditions requires for the wisdom of crowds to operate were probably absent in the referendum. But this is a tricky argument, and an impossible one to make in the idiot-speak of BBC current affairs programmes.

** Actually, third: the first was in 1975.

*** This would put Tory Brexiters on a nice hook: to call for Brexit they would have to argue that Corbyn had struck a better deal than May.

December 17, 2018

Brexit, & limits of empathy

���The trouble with you son��� said Bill Shankly once to a struggling young player ���is that your brains are all in your head.��� The great man had a point, and not just about football.

What I mean is that there are some things which we recognise intellectually but which we just don���t get in our hearts or guts. There are limits, therefore, to how far we can empathize with others��� views, even if we try (which, of course, many people don���t).

For me, religion is like this: although I can, with effort, see that there could be an intellectual argument for the existence of God I don���t get what it means to have religious faith. I just cannot imagine having such a thing. I struggle therefore to empathize with those that do.

I have the same trouble with Brexit. My brain tells me that there might be a case for trading off some prosperity for greater sovereignty, greater democratic control over our country���s affairs. But I don���t , in my heart, feel the attraction of such sovereignty. And I struggle to even imagine doing so.

IS the fault here mine, or Brexiters?

It could be mine. Coming from a poor background has caused me to value wealth highly ��� maybe to over-value it. It���s no accident, I suspect, that so many prominent Brexiters were raised on the other side of the tracks to me: Johnson, Banks, Farage, Rees-Mogg and so on. My education in economics might well have reinforced this bias. All professions are prone to deformation professionelle, and a tendency to overvalue the material world might be one of economists��� biases. (By the same token, this upbringing also blinds me to the attraction of ���ever closer union��� within Europe except insofar as this brings material benefits).

Also, sovereignty is a collective good; it���s something possessed by we, not me. My education into liberal individualism might well have biased me against seeing the value of collective goods and to prefer individual ones: Talk of a ���national story��� leaves me cold, as does the prospect of the UK being able to set its own regulations upon the manufacture of vacuum cleaners. I want to know what I am supposed to do with sovereignty ��� which is why I value personal autonomy more. But this could just be my materialist-individualist upbringing.

Or is it? Maybe I���m right and it is Brexiters who are over-rating sovereignty. Certainly, Lexiters are overstating the benefits of escaping limits on state aid. As Ewan McGaughey points out, such limits curb crony capitalism but not socialistic objectives such as infrastructure spending. Granted, EU rules also enforce capital mobility and market competition, but these aren���t incompatible with my conception of socialism.

Also insofar as sovereignty means more power for national governments it empowers our opponents as much as ourselves. The belief that it will be used beneficially, I fear, rests upon an optimism bias ��� the idea that the right side will win power.

But again, I might be missing the point. Maybe sovereignty is an intrinsic good, valuable in itself even if it isn���t exercised.

Or perhaps there���s something else going on. Some people want some things not because of their intrinsic or instrumental value but for ego-gratification: think of bosses enforcing petty rules that don���t enhance productivity, or middle-aged men chatting up younger women or investment bankers wanting bigger bonuses than their colleagues. From this perspective, the mere fact that Brexit is wanted makes some Brexiters desperate for it.

All this leaves me puzzled. I don���t even know what type of good sovereignty is supposed to be, let alone whether or how it can be priced. And what���s more, I don���t know whether the fault here is mine or others. Which makes me wonder: am I really the stupidest participant in the Brexit debate?

December 13, 2018

When bad government matters

Here���s a nice contrast. On the one hand, Tim Stanley says:

Britain's still absolutely fine, by the way, probably better off than its ever been. It's just politics that's a mess. If you think this is the Apocalypse, which some people apparently do, then you haven't lived long enough or travelled far enough.

But on the other Tony Yates says that ���the difficulties we face now have the potential to be much worse��� than the financial crisis of 2008.

I agree with both.

The government is obviously a shit-show. But the messy Brexit negotiations are ��� so far ��� having only a small impact on real life. Yes, it���s plausible that they are adding to the output cost of the original decision to leave. And they seem to be contributing to weakness in the housing market. And they have forced down sterling which will raise import prices slightly. But on the other hand, their impact upon the stock market has been small ��� much smaller than the impact of gyrations in global markets. Net, these are minor irritations ��� much less than the everyday hassles of traffic jams, stressful work and troubled relationships.

For those of us outside of the Westminster bubble, life is going on as normal. Westminster politics is like my garden ��� an ugly mess but only if you look at it. In this sense, Tim is right. For someone wise enough to ignore day-to-day politics, life goes on as normal.

But Tony might also be right. What matters here is the distinction between government and the state. The government is a mess. But the state, to some extent, is not: the NHS is carrying on as usual, taxes and benefits are being paid and so on. (An exception, here of course, is that there is state failure in that Universal Credit is being maladministered: it is this, more than the mishandling of the Brexit negotiations, for which the government deserves contempt.)

Let���s put this another way. We can think of the state as a provider of intermediate goods ��� things that enter the production process: transport links, banking regulation, the rule of law and so on. And as Chad Jones has rightly stressed, these have multiplier effects: bad law enforcement (for example) can impoverish a nation, which can limit its tax-raising powers, which can make it harder to finance good law enforcement thus keeping it trapped in poverty.

One such intermediate good provided by the state, of course, are international trading arrangements. And these are in jeopardy: how much so is, I fear, indeterminable given the high noise-signal ratio.

It���s for this reason that Tony is right: less good trading arrangements have multiplier effects in the sense that less trade means less innovation and (pdf) productivity growth (pdf) and hence lower wage growth for everybody.

In the short-term ��� which can last months ��� government by Keystone Kops is relatively harmless: it might even be a good thing, insofar as it reminds young people that the world is not a meritocracy. The more sensible of us can ignore it, and the more stupid of us can treat it as a game ��� which is how Oxford Union Tories and their BBC fan club regard it. In the longer-run, though, government failure threatens state failure. And that matters ��� a lot.

December 11, 2018

Brexit's irrelevant cost

I can understand why some reasonable people want to leave the EU. What���s more puzzling is why so many think it is worth the bother. Is it worth dividing the country, triggering a political crisis worse than 2008, causing a ���toxic period��� in politics, and stealing all cognitive bandwidth from countless other issues?

In truth, though, there is an answer here. It is precisely because Brexit is proving to be so expensive that its supporters will continue to value it so highly.

One reason for this was discovered back in 1959 by Elliott Aronson and Judson Mills. They got female undergraduates to undergo initiation ceremonies (pdf) into a college sorority. For some, these ceremonies were mild, but for others they consisted in asking students to read out obscene words to the group (which was embarrassing for young women in the 1950s). They found that:

Subjects who underwent a severe initiation perceived the group as being significantly more attractive than did those who underwent a mild initiation or no initiation.

This corroborated their prior belief that ���persons who go through a great deal of trouble or pain to attain something tend to value it more highly than persons who attain the same thing with a minimum of effort.���

Dan Ariely has called this the Ikea effect (pdf). If we go to the trouble of schlepping to Ikea and then assembling one of its bookcases, we value the product more. As he says in Predictably Irrational: ���The more work you put into something, the more ownership you begin to feel for it.��� John Locke���s idea that we come to own something by mixing our labour with it might be bad law and terrible history, but it���s beautiful psychology.

By the same token, the very fact that Brexit is proving so hard to achieve will cause its supporters to value it so much. Far from applying the very wise Cushnie principle - ���it���s not worth the bother��� ��� they are as determined as ever to see Brexit through.

Aronson and Mills thought that what goes on in these cases is a form of dissonance reduction ��� an attempt to reduce the conflict between two apparently conflicting beliefs. So, if you believe ���Brexit is good��� and ���Brexit is hard to achieve���, you reconcile these two by thinking that Brexit is so valuable that it���ll be worth all the sacrifices.

As Robert Cialdini says in Influence, we have a huge desire for consistency ��� no only to hold consistent beliefs at the same time, but to have consistent beliefs over time:

Once we have made a choice or taken a stand, we will encounter personal and interpersonal pressures to behave consistently with that commitment. These pressures will cause us to respond in ways that justify our earlier decision. (Influence, p57)

Marketing departments, of course, know all this. Financial advice and university textbooks are expensive not only in an attempt to signal quality, but also to induce choice-supportive bias ��� to get us to think ���this must be good: I paid so much for it.���

Critics of mainstream economics might see this as grist to their mill. Orthodox micro assumes that for individual consumers price and marginal utility are separate things. They are, for expected marginal utility. For experienced marginal utility, however, they are not: a high price can give us higher experienced marginal utility.

This, though, is a side-point. The main point is a depressing one. The high cost of Brexit, far from being a reason not to leave the EU, is only entrenching Brexiters' opinions. Which means that the divisions Brexit is causing will last for years.

December 6, 2018

A behavioural economic case for Brexit

Is there an economic case for Brexit after all?

Superficially, it seems not. Almost all serious economists agree that less close trading arrangements with the EU and tougher immigration controls will make us poorer than we would otherwise be even in the event of a smooth Brexit, and the Minfordians protestations to the contrary are not credible.

Behavioural economics, however, suggests there might be a case. This rests upon two pillars.

Pillar one is the Easterlin paradox ��� the finding that long periods of economic growth in developed economies have not made us much happier. This suggests the blow to well-being caused by slower GDP growth will be very small.

Now, I know some of you think the Easterlin paradox is a statistical artefact arising from the fact that GDP is unbounded whereas well-being is tightly constrained, somewhere between ���ain���t dead yet��� and ���all right, I suppose���.

I���m not entirely sure. There paradox draws attention to important facts.

One is that people adapt. We become accustomed to prosperity so it doesn't make us much happier. By the same token, we also adapt to ill-fortune. Andrew Clark, for example, has shown that after apparently nasty events such as divorce or even bereavement happiness returns to its baseline quite quickly: the merry widow is a real thing. And Christoph Merkle has shown that financial losses hurt people much less than they expected.

The other is that for many of us, our well-being depends upon relative income (pdf) more than absolute. For example, one survey by Sara Solnick and David Hemenway found that most people would prefer (pdf) an income of $50,000 a year when everybody else get $25,000 than an income of $100,000 a year when everybody else has $200,000. If all of us become worse off, therefore, well-being doesn���t fall much: we���ll be comforted by the fact that we���re all in the same boat.

You might object that this is only true of Brexit ex ante. Ex post, some will suffer more from it than others. But this can be said of the normal everyday creative destruction of capitalism. And few oppose this.

Our second pillar is a finding by Matthias Benz, Bruno Frey and Alois Stutzer. They show that there���s such a thing as procedural utility. They say:

Participation rights provide procedural utility in terms of a feeling of self-determination and influence.

This is one reason why the self-employed tend to be happier than employees.

A sense of control over one���s destiny, and of having a right to a say, makes us happy even if we don���t actually exercise that right and even if the outcomes of decisions are the same.

You might object to this that nobody other than a minority of cranks much cared about sovereignty before 2016. True, but irrelevant. They care now. And this is what matters.

If we put together the Easterlin paradox with the finding that procedural utility matters, we have a clear implication: the loss of income caused by Brexit won���t much hurt us whilst the gain to national self-control should increase well-being.

Brexit trades off income against sovereignty. Behavioural economics suggests this is a bargain which many people might rationally want. The fact that a slim majority chose to make this trade-off is therefore reasonable - perhaps more so than they knew at the time.

So, how convincing is this argument? I'm not sure. I���ve two quibbles with it.

One is that the Easterlin paradox is a story about economic growth, not about the lack of it. Just because growth doesn���t make us much happier, it doesn���t follow that the lack of it will be harmless. In an environment in which we might well suffer capitalist stagnation anyway, Brexit raises the risk of a flatlining of incomes for a long time. Maybe 2% real growth per year versus 2.5% is no big deal. But 0.5% versus 1% might be. As Ben Friedman has shown, weak growth creates intolerance and closed-mindedness. For some Brexiters, of course, this is a feature not a bug but I disagree.

Secondly, there must be less cack-handed and divisive ways of increasing procedural utility than Brexit ��� such as greater worker democracy or means of giving clients a greater voice in the provision of public services.

I���m not sure, therefore, that all this is a convincing argument for Brexit. But it is, I think, a strong one ��� and certainly better than almost all Brexiters have managed. Which for me raises a puzzle: why haven���t they argued more along these lines?

December 5, 2018

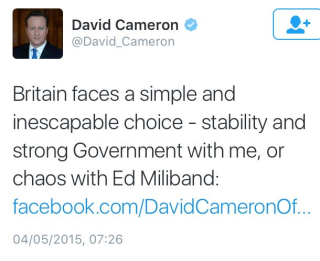

"Chaos" with Ed Miliband

David Cameron���s infamous 2015 tweet that we face a choice between stability and strong government under him or chaos with Ed Miliband has long become a joke ��� a clich��, admittedly, but a good one. In a sense, this is unfortunate because it contains some truth: from a Tory point of view, a Miliband government would indeed have been chaotic.

This isn���t because he too would have unleashed the Brexit clusterfuck. He wouldn���t. Back in 2015 less than 10% (pdf) of voters thought that the EU was the country���s most important issue. Cameron called a referendum not because there was mass pressure for one but to try to silence a handful of cranks in his own party. Miliband wouldn���t have needed to do that.

Instead, he���d have caused ���chaos��� in three other ways.

First, his administration would have seen policy mis-steps, poor administration and ministerial gaffes: all governments do. Because political reportage lacks perspective, hyper-ventilating reporters would exaggerate these into episodes of grave perils. What Michael Oakeshott wrote in 1962 is perhaps truer now than then: ���political life is resolved into a succession of crises.��� We���d thus have ���chaos��� even if it were only about the misuse of paperclips at the Department of Administrative Affairs.

Secondly, the purpose of politics in capitalist society is not to provide good administration. It is to ensure the power and prosperity of the rich. Labour would not have done this as well as the Tories. Its policies (pdf) to tax bank bonuses, clamp down on tax-dodging, support coops and give workers a say on bosses��� pay were all threats to the power of the rich. Of course, they were mild ones: but faced with any threat at all, the over-entitled rich cry like spoilt brats (see Digby Jones, passim).

Remember: the Tories think the 1970s were a time of crisis and chaos. But in fact real wages rose nicely then ��� by 1.8 per cent per year according to Bank of England data. So where was the crisis? It was in profitability and in militant workers challenging capitalist authority. That���s what matters.

You might have an obvious objection here: doesn���t Brexit threaten profitability? It does. But no more than it threatens wages. Brexit will make us all poorer. For many, though, this doesn���t matter because income and wealth are positional goods (pdf). As Andrew Oswald has said (pdf): ���what matters to someone who lives in a rich country is his or her relative income.��� For many, Brexit is tolerable because it doesn���t much disrupt relative incomes. What would be intolerable is the threat to the relative incomes of the rich posed by even the mildest of social democrats.

Thirdly, the Tories don���t understand the left*: the fact that some believe Jeremy Corbyn is a Marxist tells us this. This fact alone means that a Labour government would create uncertainty. And we���ve known ever since the work (pdf) of Daniel Ellsberg that people hate uncertainty. A Labour government would thus appear chaotic to Tories even if it looked stable to Labour supporters.

This sense of chaos would be reinforced by something else ��� that fact that we never see counter-factuals: that���s why they���re called counter-factuals. A world in which Ed Miliband is three years into his premiership would not be one in which there was a Jim Bowen showing voters our current Tory government and saying ���here���s what you could have won���. (And even if there were, nobody would believe him.) Nobody would therefore credit Miliband with saving from the Brexit clusterfuck. And the Tories would be able to pose as a credible alternative government. The contrast effect would thus make a Miliband government look bad.

So Cameron was right. A Miliband government would have been ���chaotic���. This tells us a lot - although absolutely nothing about Mr Miliband.

* The left doesn���t understand the right either, but that���s not my point here.

December 4, 2018

Blind to luck

In a good article on how graduating in a recession does long-lasting damage to one���s career, Tim Harford says ���it���s easy to overlook luck.���

It is indeed. Evidence for this has been uncovered in experiments by Nattavudh Powdthavee and Yohanes Riyanto. They got students in Singapore and Thailand to bet upon tosses of a fair coin and found that people were willing to pay to back the bet of students who had correctly called previous tosses. ���An average person is often happy to pay for what could only be described as transparently useless advice��� they conclude.

This is startling. But it has been corroborated by other research: experiments in Barcelona have found exactly the same thing.

It���s also been found in the real world. This paper finds that investors:

fail to understand that, in large populations of mutual funds, a few will outperform by pure chance...In addition, investors do not sufficiently account for volatility and are thus likely to confuse risk taking with skill. In large mutual fund populations, this can lead to an over-allocation of capital to lucky past winners.

People over-estimate the signal-to-noise ratio in what is really volatile data, and so under-estimate the role of luck. A recent paper by economists at Elm Partners shows this. They asked people: how many tosses would you need to see to be 95% confident of distinguishing between a far coin and one with a 60% chance of coming up heads? The correct answer is 143. But most subjects answered 40 or less.

All this suggests people are indeed blind to the importance of luck and are too quick to see patterns: the technical term for this is apophenia.

The truth is, though, that luck is everywhere. William Goldman famously said that ���nobody knows anything���, and that success is largely unpredictable. But nevertheless we laud those who are lucky enough to have backed success as if they know what they were doing. As Ed Smith writes in his lovely book, Luck: ���randomness is routinely misinterpreted as skill.���

Why do people do this? I suspect it���s not just because of a lack of statistical literacy: many of the subjects in the experiments I���ve cited had taken statistics classes. It���s also because of two reinforcing biases. One is the outcome bias. We judge a performance by its result so if a team wins the game, or if a fund manager beats the market, we infer that they did well rather than got lucky. The other is the narrative fallacy. We are story-telling animals. We seek links between things and detailed explanations even if the truth is only that a bit of good luck happened, then a bit of bad. I suspect that most football punditry is like this.

All this is about how we attribute skill rather than luck to other people. But of course, we also do so to ourselves, and asymmetrically: good results are down to skill and bad to luck. A study of day traders has confirmed what you probably suspected:

Retail day traders in the forex market attribute random success to their own skill and, as a consequence, increase risk taking.

The upshot of all this is that the successful are apt to become bumptious arrogant prats because they attribute their success to their own talents rather than luck. And observers are apt to take them at their inflated self-estimation.

Why for example did the housing, communities and local government select committee ask Mike Ashley yesterday for his views on reviving high streets? Does Mr Ashley really know more than anybody else with years of working in retail? Or were MPs failing to see that companies can succeed in much the same way that some species do ��� because the environment selects for mutations which are in fact random and unintended? The mere fact the question is rarely asked (not just of Ashley) is itself significant.

This, of course, colours our whole social and political structure. Our tendency to see skill where there is just luck causes the successful to have an exaggerated sense of entitlement and the rest of us to be overly deferential to them. Very few people are luck egalitarians. This is one way ��� of perhaps many ��� in which inequality sustains itself.

December 2, 2018

Changing the agenda

It���s hard to believe now, but only three years ago the country was not divided between Brexiters and Remainers. In fact, the very idea of such a split would have seemed as absurd as Swift���s division between big-enders and little-enders. Yes, there were a few fanatical Brexiters but most of us gave the matter no thought - including, we now know, most Brexiters themselves. It was a low-salience issue.

This fact has enormous implications for how we should think about Labour party policy.

It shows that it is possible for a government to shift the political agenda. Cameron���s simple trick of holding a referendum transformed our political priorities. Despite the fact that the Brexit negotiations have been an utter shambles, this might actually have benefited the Tories as it has distracted people from the government���s many other failings. If the media weren���t obsessed with Brexit, it might devote a little more attention to the collapse of the railway network, inadequate mental health care, rising homelessness, wage stagnation and the many other effects of austerity.

Cameron has shown that we don���t necessarily need a popular political movement to change the agenda. It can also be done by one-off top-down policies, which can themselves then build movements, as Cameron created Leavers and Remainers.

It���s in this context that we should interpret Labour���s plans to give customers a say on executive pay or to expand worker ownership. It is of course wholly reasonable to question whether such policies, as they stand, will work*. Doing so, however, sometimes misses a Big Fact ��� that these are not merely technocratic fixes.

Instead, they are efforts to change the political culture. For too long, the question of how much pay and power bosses should have has been off the agenda. Giving workers and customers a say on such matters is a way of showing that such issues are important, and a means of getting people to question bosses��� rapacity and incompetence. It's a stepping stone towards worker democracy and socialism, and a step away from Westminster-centric politics.

We can also read Labour���s ��� ahem ��� constructive ambiguity towards Brexit in this light. The party���s dominant attitude to Brexit should be (and I suspect is): ���this is Tory shit; they should shovel it.��� Their priority is to keep the party together, maximize electoral advantage, and move onto the issues that really concern them: ending austerity and moving towards socialism. (This is quite consistent with opposing Brexit when necessary).

My point here is to stress a point that���s often overlooked. Politics is not merely about finding technocratic solutions to existing issues. It is also about deciding what is an issue in the first place. Those who judge Labour only on the former grounds are framing politics wrongly. And they are neglecting an important political question ��� of how, and by whom, the agenda is set.

* The details can be fixed later. If it���s acceptable for Microsoft to release beta versions of Windows and fix them months later, it���s acceptable for opposition parties, which have vastly smaller resources, to do so too.

November 29, 2018

Against debate

Everybody, it seems, wants a debate. Theresa May wants to debate her Brexit deal with Corbyn; Grace Blakeley invites her critics to ���come debate me���; and Sarah O���Connor wants a ���nuanced debate now about what we value in the economy���.

Include me out. Most debates ��� and especially televised ones between politicians ��� are worse than a waste of time. They are downright pernicious.

A debate, like many things, is a selection device. The question is: does it select for the truth, or against it?

There���s a presumption ��� best expressed by John Stuart Mill ��� that it selects for the truth. Honest and rational men, he thought, would present arguments and evidence to other rational men and so the truth would emerge:

There must be discussion, to show how experience is to be interpreted. Wrong opinions and practices gradually yield to fact and argument: but facts and arguments, to produce any effect on the mind, must be brought before it.

This is woefully over-optimistic. It���s very possible instead that debates are counter-selection devices. Far from selecting in favour of the truth, they select against it. I���m thinking of four mechanisms here:

- Some facts are hard to present in debates. Numerical data can be cherry-picked or presented out of context, with the result that the debate degenerates into claim and counter-claim. The truth about numbers is often best shown in chart or tabular form, not by talking heads. In this way, ���hard��� data doesn���t get the weight it merits in debates. But not just hard data. As Michael Polanyi pointed out, there can be tacit knowledge ��� senses of comfort or disquiet that cannot be properly articulated. This too is underweighted in debate. Debates select for articulable arguments, which means selection against both hard numbers and tacit feelings.

- Debates select not just for truth but for overconfidence. The confident assertion of a clear statement beats caution and caveats. Experiments tell us that people often mistake overconfidence for competence thereby selecting for it and against actual ability. Debates favour articulate overconfident posh folk who in fact know nothing ��� which is why we got into this mess.

- Lies can win. Mill assumed that interlocutors would present facts. But this isn���t necessarily true. As Tim Harford has said, ���a simple untruth can beat off a complicated set of facts simply by being easier to understand and remember.��� As we saw in the Brexit debate, with claims that Turkey was about to join the EU and that leaving would give the NHS ��350m a week, bare-faced lied can gain credence. Selection for dishonesty isn���t necessarily a problem if we are choosing our next Prime Minister: I���m happy to have a lying bastard deal with Putin and Trump. But it is if we want to ascertain the truth of an issue.

- Debaters appeal not to reason but to cognitive biases. Mill assumed, implicitly, that audiences were good Bayesians who would yield in the correct fashion to ���fact and argument���. We now know that they are not, that all of us (yes, even me) are a mass of cognitive biases. Debates can be won not by the side with the most rational arguments and strongest facts, but by those who best appeal to our irrationality. This, I suspect, was the genius of the Brexit campaign: it harnessed such biases as wishful thinking and prospect theory whilst remainers were mired in abstract facts about GDP.

On top of these adverse selection mechanisms, debates have another baleful effect. They are polarizing. If we ask ���who���s right?��� we cannot build consensus. This problem is magnified by a phenomenon first pointed out in 1979 by Charles Lord, Lee Ross and Mark Lepper. They showed people mixed reports on the effects of the death penalty. They found (pdf) that, after reading these reports people who supported capital punishment became stronger in their support, whilst opponents of the death penalty also became more dogmatic. Even balanced and factual data thus produce polarization and extremism, through mechanisms we now know as asymmetric Bayesianism and the backfire effect.

As evidence for all this I need only point to Brexit. We���ve now had three years of debate about it. The result is ignorance and division. Or just watch Question Time, or any other of the endless "posh twats talk shit" shows that pollute the airwaves.

I���m not saying that there is no point to political discussion. Instead, such discussions, if they are to be useful, must be carefully structured. There are strict rules on how court cases should be conducted and what evidence is admissible. The same should be true for political deliberation.

In its current form, political debate perpetuates the idea that the road to power lies in the ability to rationally persuade people. This is a lie.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers