Chris Dillow's Blog, page 32

March 19, 2019

Beliefs and interests

���It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his job depends upon not understanding it.��� The spectacle of rightist and centrist journalists trying to absolve the MSM of blame for the rise of Islamophobia reminds me of Upton Sinclair���s famous quip.

They, of course, are by no means the only people at whom one might direct this accusation. Many of you us might also point it at: fund managers who deny the efficient market hypothesis; mainstream economists who reject some heterodox approaches; managerialists who stick to using crude targets; or centrist MPs who fail to see the need for new economic policies. And so on.

But I wonder: what exactly is the mechanism that Sinclair and those who quote him have in mind?

I doubt that many of us deliberately and consciously adapt our beliefs to our interests. We don���t think ���X is false but it serves my interests so I shall believe X���. For example, a Tory government is probably more in my financial interest than a Labour one, but I struggle to find sympathy for the Tory party.

I suspect instead that other mechanisms are at work.

One is wishful thinking. This is not a deliberate process. Instead, as Jon Elster has said, it operates behind our backs, subconsciously. An experiment by Guy Mayraz has shown just how easy it is to induce this. He asked subjects to predict future moves in the price of wheat. Before doing so, he randomly divided them into two groups: "farmers" who would profit from a rising price, and "bakers" who would profit from a falling one. He found that farmers predicted higher prices than bakers. And they continued to do so even when they were given incentives for accurate predictions.

We all want to believe we are the good guys, and the wish is father to the belief; nobody really wants to believe they have contributed to mass murder. The joke in David Mitchell���s famous question ���are we the baddies?��� is that he and his comrades had not asked that before.

A second mechanism is that we can distort our evidence-gathering. Jon Elster describes this:

Initially, let us assume, the evidence does not support the belief that I would like to be true. I then proceed to collect more evidence, adjusting and updating my beliefs as I go along. If at some point the sum total of the evidence collected so far supports my preferred belief, I stop. I can then truly tell myself and others that my belief is supported by the available evidence (Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences, p 37-38)

This is one reason why many clever people can (perhaps) be just as biased as stupider ones: they have more ways of gathering evidence and rationalizing it.

A third mechanism is professional deformation. This is the tendency for our training ��� into all professions, including economics ��� to inculcate not only techniques and knowledge but also biases, groupthink and blind spots.

Take, for example, Andrew Norfolk���s reporting of the Rotherham child sex abuse scandal. Here, there was a trade-off, between a strong and important story on the one hand against the danger of stoking up Islamophobia on the other: Mr Norfolk saw at the time that his story was ���a dream for the far-right��� and the Christchurch murderer wrote ���For Rotherham��� on his ammunition. Journalists��� professional upbringing is to favour publishing the story. And rightly so: it was true, and only a warped mind would see it as a reason to hate Muslims.

If that case is clear cut, though, what about Newsnight inviting Generation Identity onto their programme. Does the desire for ���good debate��� overcome the risk of publicizing fascism? And what about countless comment columns disparaging Muslims? Does the truth-value of these really outweigh the danger of encouraging the far-right.

In all these cases, journalists��� professional presumption is to ���publish and be damned.��� This is often a laudable instinct. But it is only a partial perspective, one which a journalist���s training perhaps exaggerates*: journalists are often selected for and socialized into a strong belief in free speech. That biases them against seeing that such speech has a cost - and they are especially slow to see this if they don't want to.

My point here should be a trivial one, but I fear is overlooked in our histrionic environment. We are all prone to countless biases: yes, all, not least me. Sinclair���s remark should be seen not as a description of a conspiracy, but of how these biases can operate together.

* The cost of trashy right-wing columns isn���t just (or even perhaps mainly) the stoking of Islamophobia. It���s the denial of space for discussion of other issues: if we���re debating fascism we are not debating other things.

March 17, 2019

On class difference

A friend tells me that when I started my first job in an investment bank I did not speak for the first three weeks. He exaggerates, but not much. What I was doing was working out the unwritten rules of how to behave in an alien environment.

I was reminded of this by reading Tony Connelly���s description* of Geoffrey Cox���s behaviour last week in Brussels: he boasted of not having visited the city for 40 years and angered Sabine Weyand by calling her "my dear." Mr Cox did not do what I did - shut up until you've learned what to do.

Herein, I think, lies a class difference. If you are upwardly mobile from a poor background, you have to learn how to fit in. If you are posh, you don���t. You glide from school to Oxbridge to the city or bar all the time surrounded by like-minded people so you know the rules. The upshot is that in the unusual contingency of ever being outside of that environment ��� as Cox was in Brussels ��� you put your foot in it.

We should read Cox���s behaviour alongside Boris Johnson���s claim that the inquiry into historic sex abuse is money ���spaffed up a wall���. (Mr J, of course, is no stranger to wasting public money). Both, I suggest, are examples of the arrogant insensitivity that results from not having to work out how to consider the sensitivities of those outside your group. (When those sensitivities are upset, of course, it is political correctness gone mad, rather than what it is ��� the result of crass behaviour.)

At about the same time I was in purdah my contemporary Mr Johnson was being sacked by the Times for lying. Which highlights another class difference. Those of us from poor backgrounds know we don���t get many chances so we must take those we get: there are no second acts in working class lives. Had I been sacked from my first job for dishonesty, I doubt I���d have got another chance. Posh people do get other chances. And both sides know this.

My point here should be a trivial one. Background determines character, so rich backgrounds tend to generate different characters than poor ones. I���d suggest other differences, all of which should disqualify most posh people from politics:

1. If everything comes naturally to you, you don���t need to think so much about how to get it. So you under-invest in learning how to hustle, negotiate or strategize. (Is it really an accident that the western politician who most mastered these arts, Lyndon Johnson, came from a poor home?) This might be one reason why Brexit has gone badly. Having spent his entire life thinking he could get what he wants simply by asking, Jacob Rees-Mogg has been disturbed to find that the EU doesn���t work like that.

2. Posh people have confidence ��� too much of it: it was overconfidence that led Cameron to call that referendum. Because people mistake confidence for actual ability, this lends them a credibility denied to others, which is reinforced by the dominance in the media of other posh folk. If Johnson and Rees-Mogg had thick Brummie accents, how would the media treat them?

3. The rich don���t appreciate just how important money is. For a poor family, an extra fiver at the end of the week can make the difference between relief and misery. This warps their political priorities. Whereas I regard economic growth and redistribution as the main political issues, the rich have others ��� Brexit if you are on the right, Palestine if on the left.

4. If you are surrounded from birth by other rich people, you lack a gut understanding of how others live. You are prone to the middle England error ��� of over-estimating the incomes of ordinary people. This means that even the most well-meaning are apt to conflate the national interest with that of the wealthy. What���s more, you never get a true grasp of what poverty really means. It���s not just about a lack of money, but about a lack of opportunities and role models: the first people I met with degrees who did not work in the public sector were the guys who interviewed me for that investment bank job. And it���s about insecurity too: if you are ���just about managing��� you are only one decision away from abject poverty. One of the greatest days of my life was the realization, sometime in my thirties, that I would never be homeless. Some of you reading this won���t understand that. As one of the key texts on class has it:

You will never understand

How it feels to live your life

With no meaning or control

And with nowhere left to go

5. Trust. We naturally trust those like ourselves. Which means that posher politicians are apt to surround themselves with other posh people. This isn���t a purely rightist trait: think of Andrew Murray and Seamus Milne working for Jeremy Corbyn. It also means they are more likely to take advice from other posh folk, leaving then vulnerable to undue influence from the rich.

Now, I should caveat all this. It is possible ��� with effort - for the rich to understand this. One or two do. But even for these, there���s something missing. Just as religious converts lack the visceral knowledge of their faith that comes from having been raised in it, so posh people lack such understanding of poverty. As Bill Shankly said: ���the trouble with you son is that your brains are all in your head.��� Perhaps the tragedy of Tony Blair embodies this. His success lay in an awareness of what mattered to working people: money and crime. His failure came when he forgot this and was seduced by foreign policy.

Here, though is the thing. Despite Disraeli's famous quip that rich and poor are two nations formed by a different breeding this hasn���t always been the case. For much of the 20th century there was a massive mitigation of these tendencies. Military service forced posh men into close relationships with poor ones, thus broadening their perspective. As the Times��� obituary of Lord Carrington says:

He found himself sleeping in a hole beneath his tank with his four crew who came from poor backgrounds and had suffered hardship during the pre-war years. The experience shaped his politics, he said later. ���You could not have got a finer or better lot than they were. They deserved something better in the aftermath of the war.

This is not atypical: in my first job most equity salesmen had army backgrounds and so were accustomed to working with people from working class backgrounds.

One cost of living in a less militaristic society, however, is that this influence is much diminished and that posh men are therefore more distant in consciousness from the rest of us: the contrast between Lord Carrington and Boris Johnson ��� both former foreign secretaries ��� perhaps embodies this.

* an account which shows that Irish coverage of Brexit is an order of magnitude superior to the British.

March 15, 2019

The need for class politics

We need to talk about class. Since Jess Phillips��� interview with the Times there���s been a lot of talk about whether she is authentically working class. This is, as Suzanne Moore says, mostly guff.

We need a Marxist perspective here. To us Marxists, class is not just another identity or another lifestyle ��� a matter of whether you drink in Wetherspoons or wine bars or shop at Waitrose rather than Lidl. Instead, it is an objective fact about your relationship (pdf) to the means of production. If you lack ownership or control of these, then you are working class ��� in a position of exploitation or domination. If you do have ownership or control then you are capitalist, or bourgeois.

There are of course nuances here. You can be an exploiter without dominating someone: we can, for example say that footballers exploit systematically loss-making club owners, or that senior bank managers and traders exploit shareholders. Conversely, you can be a dominator without being an exploiter: think of low-level managers on poor wages tyrannizing their staff. And then of course there are what Erik Olin Wright called contradictory class locations ��� such as middle managers who can extract some rents for themselves but who are also subject to control from above. Nor is all wealth the product of capitalist exploitation: we wouldn���t really call, say, J. K. Rowling a capitalist.

These nuances, however, don't alter the fact that by this standard the working class is not the libelous fantasy that much of the metropolitan media pretend. It is not a homogenously white group of racist northerners. It contains people of all races, and even those earning very good money.

Does this notion of class matter? Of course, it has never been a perfect predictor of political attitudes. Working class Tories and leftist capitalists are as old as capitalism, and racism can be found among the bourgeoisie as well as workers. And I think there is something to be said for non-Marxian conceptions of class: for example, there are reasons to distrust the prevalence of posh people in politics.

Nevertheless, the Marxian idea of class does matter. For one thing, it is an objective fact that millions of people live lives of poverty, unfreedom and insecurity because they lack access to capital*.

And for another, it does help explain the popularity of Corbynism among the so-called ���middle-class���: at the last election, 35% of ���ABs��� voted Labour. Many people even in erstwhile good professions have no hope of owning property and face stress and domination from their managerialist overlords. The harm caused by class division extends far up the income ladder. Even quite posh people are working class ��� however many avocados they eat - and many of them vote accordingly.

You might argue that if so many people are working class then the definition is useless. Far from it. The fact that they are vindicates Marx���s claim that ���the lower strata of the middle class sink gradually into the proletariat." It also means that class makes for a less divisive type of politics. Whilst identity politics risks splitting us into countless hostile groups ��� made more bitter because they are personalized - class politics can unite most of us**. And it can do so in a more humane way. Class is a matter of social structure, not of goodies against baddies. This should take personalities out of political discourse and so permit more sober analysis. I know it is an odd thing to say given the historical record, but Marxism has the potential to be a more civilized type of politics than we currently have.

* But remember Joan Robinson's quip: "the only thing worse than being exploited by capitalism is not being exploited by capitalism."

** Well, actually you. By the definition I���m using I���m less working class than most of you. My shareholdings are sufficiently big that I can almost afford to retire. (And I���ve never been into Greggs, although I often go into Wetherspoons, albeit in Stamford and Oakham.)

March 14, 2019

Why government borrowing has fallen

Phillip Hammond said yesterday that the public finances ���continue to improve��� ���thanks to the difficult decisions we have taken in the last nine years.��� This is not quite correct.

To see why, imagine that people and companies were to save a constant fraction of their disposable income, come what may, in the face of fiscal austerity. As their incomes fall in the face of that austerity their spending would therefore fall one-for-one. That would further reduce aggregate demand which would in turn cut the government���s tax receipts and add to government borrowing. We���d then suffer a severe paradox of thrift, in which everybody���s efforts to save more would lead to weaker incomes for all and hence to lower savings.

This tells us that governments can borrow less if and only if somebody else borrows more or saves less. This is in fact trivially true. Every pound borrowed is a pound lent. One person���s net borrowing can therefore fall if and only if somebody else���s net lending falls.

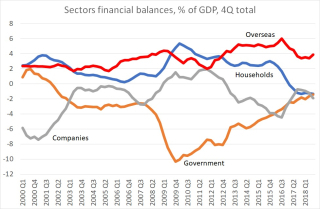

My chart shows the point for the four main sectors of the economy. It shows that government borrowing has steadily declined since 2009. The counterpart to this, however, has been a sharp swing in household net lending. For example, in the 12 months to September 2010 they were net lenders of 4.8 per cent of GDP: they were saving a lot and borrowing little. In the 12 months to September 2018 (the latest period for which we have data) they were net borrowers of 1.3 per cent of GDP. This swing of 6.1 percentage points is by far the biggest counterpart to the 8.2 percentage points fall in government net borrowing. It is mainly due to a decline in the household savings ratio.

We can therefore tell a different story about why government borrowing has increased. It���s because, in response to austerity, households saved less and borrowed more in an attempt to maintain their spending: companies have also borrowed a bit more too. This supported aggregate demand and hence employment and wages ��� which allowed tax revenues to hold up as spending was squeezed.

In this sense, the government has not cut borrowing. It has only privatized it ��� shifted it from its own account onto households.

Herein lies the reason why the OBR foresees only a small further reduction in PSNB ��� from 1.1% of GDP this year to 0.5% by 2023-24. It���s because it foresees no great change in households or corporates net borrowing: see chart 3.28 on page 59 of this pdf.

My point here is that the public finances are never fully ���under control���, despite the claims of many people who should know better. Government borrowing depends upon the actions of the private sector ��� actions over which policy-makers have only limited control. If the private sector chooses to borrow a lot (as it did at the turn of the century) the government will be a net saver. And if the private sector borrows a lot ��� as it did after the 2008 crash ��� government will be a net borrower.

One Big Fact tells us this. It is that official forecasts for government borrowing are usually wrong. Since 2000 the average error (regardless of sign) in forecasts for PSNB made in the spring for the following fiscal year has been 1.1 percentage points of GDP - ��24bn in today���s money*. Even excluding 2008-09 (when borrowing was 4.4 percentage points of GDP more than forecast) the average error has been 0.9 percentage points of GDP. Such big errors are inconsistent with borrowing being fully under control: if it were, it���d be perfectly forecastable. But they are consistent with borrowing responding to the private sector���s decisions to save or borrow.

So, Mr Hammond is wrong. The fall in government borrowing is not due to his government���s ���difficult decisions��� ��� difficult for other people of course. It is due to a decline in private sector savings.

* Historical forecasts are here. Out-turns are in table PSA5A of this pdf.

March 10, 2019

Matches matter

Jess Phillips thinks she���d be a good PM. I tweeted this morning that this is more a sign of her overconfidence than it is of her ability. I did so for two reasons.

First overconfidence, whilst not universal (pdf), is widespread among those in prominent positions. Underconfident people don���t apply for such jobs, unless pushed, and so are filtered out whilst there is no similar filter against the overconfident. Quite the opposite. Hirers tend to mistake overconfidence for actual ability and so hire the overconfident: one can easily imagine Ms Phillips fluent confidence making a good impression at her CLP.

My base rate probability, therefore, is that Ms Phillips is expressing an opinion typical of MPs ��� or at least those who court publicity ��� rather than giving us a diagnosis of her actual ability.

Overconfidence, though, can be hugely damaging. Daniel Kahneman has called it the most dangerous of all cognitive biases. The three worst decisions in the UK in the last 20 years ��� Blair���s war in Iraq, RBS���s takeover of ABM Amro and Cameron���s calling a Brexit referendum having created the conditions in which he might lose one ��� were all motivated in large part by overconfidence.

A useful corrective here has been provided by Charlie Munger. It���s important, he says, to know the edge of your competence ��� to know what you���re good at and what you���re not.

There���s a second reason why I think she���s being overconfident. It���s that the honest and true answer to the question: ���would you be a good PM?��� is ���I don���t know.���

Ole Gunnar Solskjaer shows us why. His CV as a manager is vastly inferior to Jose Mourinho���s, comprising a mediocre spell at Cardiff and some success in a third-rate league. But he seems to have transformed Manyoo. This is because Mourinho was a terrible match for the Manyoo job: his brand of safety-first football was ill-suited to a squad of young attacking players and to a fanbase that expected expansive football. Solskjaer on the other hand is a much better match.

This applies to many top jobs in business and politics: what matters is not just somebody���s strengths and weaknesses but rather the match between these and the job requirements. If a company���s problem is poor cost management, for example, it needs a cost-cutter as CEO rather than a marketing man, and vice versa. As Boris Groysberg has shown (pdf), what matters for corporate performance isn���t so much a bosses��� CV as the match between his strengths and the company���s needs.

Winston Churchill���s life embodies this point. He was a terrible match for the job of First Lord of the Admiralty in 1915 and for the job of Chancellor (pdf) in 1925. But he was the right match for the position of PM in 1940.

Which is why we cannot say whether Ms Phillips would be a good PM or not, leaving aside her personal policy preferences. For any complex job we must ask what qualities it requires and what personal weaknesses can be forgiven or glossed over, and we must then ask who fits those strengths and weaknesses. Churchill was a great PM in 1940 because we needed his belligerence. Cameron was a disaster because his overconfidence was misplaced, and May is doing badly because her lack of interpersonal skills is a terrible weakness when we need a good negotiator.

But we don���t know what exactly the job requirements of PM would be at the time when or if Ms Phillips becomes a plausible candidate for the job. She might make a good PM. Or she might not. It depends upon the circumstances.

Herein lies one of my (many) beefs with politics. Many people don���t think this way. Instead, they have a cargo cult mentality. We saw this in the recent row about Churchill: too many wanted to see him as either hero or villain and not as what he was - sometimes the wrong man for a job, and sometimes the right. Too many people think a great leader will transform an organization without asking what the mechanism is or whether what makes a great leader is context-dependent. Churchill and Attlee were both great PMs, despite having utterly different characters: they were good matches for what was needed at the time. Many people rightly deplore the cult of Corbyn. But they themselves fall into a similar error. I���ve called Bonnie Tyler syndrome ��� holding out for a hero.

The truth is, though, that there are no heroes ��� or at least we cannot rely upon one turning up. All we can look for is to put round pegs in round holes. And this requires sober analysis, not wishful thinking.

March 9, 2019

Postmodern politics

In an interview with the Times Jess Phillips says of May and Corbyn:

There is an old-fashionedness about both of them. They are of a bygone era. It���s a bit like The Good Life ��� she���s Margo and he���s Tom. Their politics are so seventies. It���s hate migrants, love miners. They���re both in this terrible situation where they���re very traditional, very stubborn, bloody difficult people.

This is a false equivalence. There���s a massive difference between the two. May���s hatred of migrants has ruined lives: caused the deportation of British citizens, forced people out of work and denied them healthcare. Corbyn���s 70s politics has had done much less damage*.

What we have here is an example of a dominant but under-appreciated feature of our age - a postmodern politics in which words and appearances are everything and consequences and reality are nothing.

Now, I stress that Ms Phillips is perhaps the least of offenders here: her stance on domestic violence, for example, betokens a lively awareness of ground truth.

Instead, what she���s given us is an example of something described elsewhere in the Times by Janice Turner. As she says ���deeds matter far less than words���. So, for example, Davos men ���espouse philanthropy while recoiling at any mention of tax���, and men who take private jets can establish their green credentials with just a few words.

There are though, many more examples:

- Brexiters obsess about trade deals, oblivious to the fact that these do little to actually boost trade, and to the fact that membership of the EU is not the binding constraint upon the UK exporting more to non-EU countries. This makes sense only if we regard trade deals as an end in themselves, an expression of our sovereignty rather than as a means to greater prosperity.

- The Tories and centrists ��� with the connivance of the BBC ��� have redefined the economy to mean the public finances, where what matters is giving the impression of being in control of government borrowing: the truth, of course, is that no such control exists as government borrowing is the counterpart of private net saving. As John Kay has said, we have ���government by announcement��� in which policy statements are all that matter to the exclusion of ground truth.

- The BBC is keen to report splits and gaffes but recoils from detailed policy analysis. As John Humphrys said when asking what type of Brexit Leavers wanted, this is ���all getting a wee bit technical and I���m sure people are fed up to the back teeth of all this talk of stuff most of us don���t clearly understand.��� That was more than two years after the referendum; in a rational reality-based policy the issue would have been resolved long ago.

- The likelihood that austerity has shortened life expectancy and caused tens of thousands of deaths has been under-reported on the BBC. And when somebody tries to mention this fact ��� as Aditya Chakrabortty did on Question Time last year ��� they are treated as if they have committed a gross solecism. Which in fact they have ��� of bringing reality into a politics which attempts to deny it.

- For the centre and right, the financial crisis was like the Gulf war for Jean Baudrillard: it did not take place (pdf). They show no sign of having learned that capitalism is more fragile and less dynamic that we thought in the 1990s, and so we require very different economic policies.

What we have, therefore, is a politics of hyper-reality wherein:

What passes for reality is a network of images and signs without an external referent, such that what is represented is representation itself.

Our problem is not merely that politics has been distorted by fake news and Russian money. It is that mainstream politicians, and much of the media, has effaced reality almost completely.

* Yes, he might well have emboldened anti-semites ��� but the material damage this has done to Jews is not (yet?) comparable to that done to many of the Windrush generation.

March 7, 2019

Against the output gap

���We should throw out all self-contradictory propositions, unmeasurable quantities and indefinable concepts��� said Joan Robinson. I���m not sure if this is universally true. But there���s one place I would like to start ��� with the output gap.

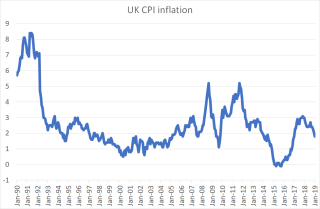

The idea here is that there is a difference between actual and unobservable potential GDP, such that inflation falls when actual GDP is below its potential but rises when it is above it.

My first beef with this is an empirical one. As Eric has said, ���the striking property of inflation of the last 20 years has been its complete invariance to shocks and policy changes.��� UK inflation hasn���t varied much since the early 90s ��� compared to its variance in the 70s and 80s - despite significant cyclical swings. And insofar as it has moved, it has been largely due to moves in oil prices and sterling. Since 1996 (when the current vintage of retail sales data begins) there has been a significant negative correlation ��� minus 0.65 ��� between CPI inflation and annual changes in retail sales. That���s hard to reconcile with the idea that inflation rises when demand hits a ���potential��� level, but easy to reconcile with the notion of inflation being driven by shocks to supply, sterling or commodity prices*.

It���s not just in the UK that the idea of the output gap has been unhelpful. The same has been true in the euro zone. Zsolt Darvas has pointed out that the ECB has over-predicted inflation for years. It���s belief that a closing of the output gap would lead to rising inflation has been systematically wrong. For example, Mario Draghi said 12 months ago that ���the economy has been growing consistently above current estimates of potential growth.��� And yet core inflation today is exactly the same as it was then ��� 1.2% (pdf).

Granted Mr Draghi went on to say that ���the responsiveness of inflation to slack has weakened in recent years��� and that ���estimates of the size of the output gap have to be made with caution.��� But these look like what Karl Popper called ���immunizing strategies��� ��� tricks to defend a theory from any attempt to falsify it.

So, what���s wrong with the output gap in theory? I���d suggest three things.

- Potential output, or capacity, is not fixed. A study (pdf) of a US steel mill by Igal Hendel and Yossi Spiegel has shown this. They show that the mill doubled production over 12 years even with the same plant and workforce because every time the mill seemed to be at ���full capacity��� its managers found ways of tweaking production methods to eke out more output. ���Capacity is not well defined,��� they conclude. This suggests that a closing of the ���output gap��� leads not to rising prices but to higher productivity. Which means that if monetary policy tightens as the ���output gap��� closes policy-makers will deprive us of productivity gains.

- Companies don���t necessarily respond to higher demand by raising prices. Back in 1986 Julio Rotemberg and Garth Saloner showed (pdf) that they might well cut prices in a boom simply because there are more customers around then and so firms will fight to win them in the hope of winning more return business in future. (This should be more likely to happen when real interest rates are low or negative, because they increase the present value of future revenues.)

- The notion of potential output doesn���t apply to the intangible economy. It might make sense to speak of a restaurant as having a level of full capacity: it has only a limited number of tables**. But what is Google���s capacity? Or Spotify���s? Or that of the computer games industry? As Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake say, one feature of the intangibles economy is its scalability. But scalability renders the notion of potential output redundant.

I suspect, then, that the idea of the output gap is a bad one. But is it dangerous?

In one sense, no. In fact, it serves a useful purpose. A central bank that targets inflation can use the idea of an output gap to conduct counter-cyclical policy. In a downturn it can say ���there���s a large output gap which will reduce future inflation, so we���re cutting interest rates.��� Even if inflation doesn���t depend upon the output gap, this is the right thing to do.

In another sense, though, the idea is dangerous. If you believe the output gap is zero then you will infer that all government borrowing is ���structural���. There will therefore be pressure upon governments to conduct unnecessary austerity.

And here lies a big and under-appreciated distinction. It is one thing to use unmeasurable quantities in one���s own personal thinking where the costs of error are small. It is quite another to use them for policy-making where bad ideas do real damage and even destroy lives. The bar for what represents a good idea should therefore be high in policy-making. And I don���t think the idea of an output gap gets over it.

* Yes, I know the omitted variables bias. Feel free to point out what these are in this case, and show their empirical importance.

** In truth, of course, the restaurant business has had excess capacity in recent years, despite the Bank of England���s belief that the aggregate output gap is small.

March 6, 2019

Growth & mobility

Everybody knows we live in an era of secular stagnation. Everybody also knows that social mobility has stalled not just in the UK but around the world. For example, a recent OECD report found that:

Since the 1990s there is a general trend towards more persistence of income positions at the bottom and at the top of the distribution. This translates into both lower chances to move upward for those at the bottom, and into even lower risks to fall down from the top.

I wonder, though: are these two facts related?

It���s obvious that economic growth provides room at the top ��� more good jobs which can be filled by people from poor backgrounds. And it also makes us better off than our parents: even 2% growth per year compounds to an 80% gain over 30 years. I���m thinking, though, of another mechanism ��� that slower growth causes hirers to become more risk averse.

A key insight here comes from Marko Tervio. He argues that what matters isn���t so much talent as proven talent. Many hirers would prefer the known quantity who is just above a threshold of competence to the unknown one who might be brilliant but might also be a duffer. In hiring a factory manager, you want someone who isn���t going to blow the place up. In hiring a journalist, you want someone who can be relied upon to file something literate and on time. And so on.

This explains a lot. It explains why there is a merry-go-round of football managers who keep getting sacked and rehired: club owners want bosses with some kind of track record ��� if not a management CV then at least a stellar playing career. It explains why Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell employ friends and family: when you have a siege mentality you look to those you can trust. And it explains why ���Failing Grayling��� keeps his job: May can at least trust him to toe the party line, and it���s only other people���s money he���s wasting.

What matters is just merit, but the expected variance around that merit. Hirers sometimes want to reduce this variance. When they do, trust trumps ability. And this is bad for social mobility. We trust people like ourselves and distrust outsiders ��� so posh white men trust other posh white men more than they do others.

And herein lies the link between slower growth and slower social mobility. It���s simply that slower growth makes us more risk averse. If you can look forward to big growth in revenues you can afford to make one or two risky hiring decisions. If you���re hiring dozens of graduate trainees you can take a risk on some potentially brilliant outsiders. If, however, your firms��� prospects are gloomier and you are hiring fewer, you���ll not take such risks.

It���s for this reason that industries that are growing rapidly tend to be meritocratic whilst those that are shrinking tend not to be. Compare, for example, finance in the 80s or IT in the 90s to journalism today.

I suspect that two other trends are exacerbating this. One is increased accountability. If you fear a bad hire will cause your boss to ask ���why did you hire that twat?��� you���ll not take a risk. Just as nobody got sacked for buying IBM so nobody got sacked for hiring the white male Oxford graduate. Another is the increased importance of soft skills. Yes, the distinction between the public school boy with his easy charm and the geeky state school boy is something of a clich��. But it has a grain of truth. It���s easier to win people over if they are like you than if they are not, which gives those from posh backgrounds an advantage in top jobs.

My point here is a variation on one that I���ve made before, following Ben Friedman. If you want an open, tolerant society in which people are treated on merit you need economic growth. And no UK politician to the right of John McDonnell seems to have any idea or interest in promoting this. Which makes any pretence they have to believe in meritocracy rather hypocritical.

March 3, 2019

The 1% vs the 0.1%

Many of you might react to the FT���s story about the ���squeezed 1%��� by getting out the world���s smallest violin. I think this is a mistake. It reminds us that the damage done by inequality extends beyond the general social and economic harm. It hurts even those who are a long way up the income ladder.

First, some statistical context. Someone at the bottom of the top percentile of incomes is on about ��120,000 a year. The top 0.1%, however, gets over ��500,000. A very well-paid head-teacher, professor or NHS consultant might just get into the top 1%, but the top 0.1% comprises bankers, very successful entrepreneurs or bosses of big firms. As the IFS���s Paul Johnson says, ���someone ���only��� at the top 1% is much more like the average person than they are like someone at top 0.1%.���

This gulf between the 1% and 0.1% hurts the 1% in three ways.

One is simply that they are aware of it. For the poor, the rich are out of sight, out of mind: in fact, they grossly under-estimate just how much the rich make. The 1%, however, see it more clearly. We compare ourselves to people like us. And the 1% benchmark themselves against the 0.1%. They are often university contemporaries, so one might resent why the no-mark who was no smarter than him is earning five times as much. Or they might compare social utilities. A doctor covered in blood will wonder why he is paid so much less for saving somebody���s life than a banker is paid for ��� well, what? And of course the 1% sees the 0.1% close up. Just as no man is a hero to his valet, so nobody in the 0.1% is a hero to his underling. Middle-managers have a lively awareness of the short-comings of senior managers, as professors do of the foibles of vice-chancellors.

All this naturally breeds resentment. Experiments (pdf) by Philip Grossman and Mana Komai have confirmed this. They split subjects into rich and poor groups and gave everybody the option of destroying another���s wealth. They found that predations by the poor upon the rich were only a minority of attacks. Instead they found that the rich attacked other rich. This is consistent with reference group theory: we compare ourselves to those like us:

We find strong evidence of within class envy: the rich targeting the rich and the poor targeting the poor. Within the rich community, the target of envy is usually a wealthier subject whose wealth is close to that of the attacker; the attacker may possibly be trying to improve his/her relative ranking.

A second effect of the gap between the 0.1% and 1% is the subject of the FT���s article. The very rich price the reasonably rich out of houses and schools: top private school fees have soared in recent years because they market themselves to the global rich. As Rick wrote:

The painful fact for many people is that their jobs no longer pay enough for them to enjoy what they had been brought up to think of as a middle-class lifestyle. They can���t afford to live in the sort of house in the sort of street where they grew up. They can���t afford to send their children to the schools they went to. And those nice leafy hospitals their parents used to go to, forget it. The super-rich can still afford these things, though, so the prices keep going up, well beyond the reach of the old middle-classes.

The difference between the 1% and the 0.1% doesn���t, however, lie merely in what they can afford. There is perhaps an even bigger difference. A man (it���s usually a man) on ��500,000 can reasonably look forward to quitting work or downshifting unless he has arranged his affairs especially badly. Somebody on a low six-figure salary, however, cannot. Instead, they often face years of stress ��� exacerbated by managerialism���s deprofessionalization of erstwhile professional jobs and to the fact that their inability to afford homes in central London condemns them to long and stressful commutes.

You will of course object here that this is also true for millions of workers far outside the 1%. You���d be bang right. And that���s the point. Class is not merely another yet another identity. It is an objective fact about your relationship to the means of production ��� about whether this puts you in a position (pdf) of subordination or domination. In many cases ��� not all but many ��� even those on six-figure salaries are in subordinate and stressful positions. They are objectively working class, however posh they might fancy themselves to be.

Which is why we need class politics. Whereas identity politics risks splitting us into mutually hostile ghettos, proper class politics has the potential to unite us ��� well most of us. One of the great marvels of capitalism is that we are so incapable of seeing this.

February 28, 2019

Why we need Analytical Marxism

I tweeted yesterday that the biggest failing of the left is that it is insufficiently influenced by analytical Marxism. I should expand on this.

Analytical Marxism (pdf) was an academic movement in the 80s which tried to reconcile Marxism with conventional ���bourgeois��� philosophy and social science. It sometimes called itself ���Marxism without bullshit���, which many took to mean Marxism without Hegelianism. Its key members included Adam Przeworski, Philippe van Parijs, Jerry Cohen, Erik Olin Wright, Jon Elster and John Roemer.

A big part of this project was the attempt to base Marxism upon methodological individualism: the basic unit of analysis is the individual, not classes ��� although of course individuals are members of classes.

This was not wholly a success. Rational choice Marxism proved to be a dead-end, which is ironic given that one of the great unions of Marxism with conventional social science has been that Kahneman and Tversky���s cognitive biases programme has vindicated and deepened Marxian theories of ideology. And I think analytical Marxists were too quick to ditch the labour theory of value and tendency for the rate of profit to fall, as they have some empirical validity (pdf).

Why, then, do I say it should be more influential than it is?

For one thing. analytical Marxism reminds us that politics is not a moral crusade. It is not about goodies versus baddies. Of course the analytical Marxists developed a powerful moral critique of capitalism. But it was a critique of a system that is unjust and oppressive. Our objection to capitalism is systemic, not that it is run by bad people. As Marx said, ���external coercive laws [have] power over every individual capitalist.���

This view stops us thinking of our opponents as bad people and therefore saves us from the idiocies into which some non-Marxist leftists have fallen: as Sean Matgamna says, ���antisemites are always perverted moralists.���

Secondly, it reminds us that political activity must be based upon a theory. You can���t achieve change simply by protesting or by demanding that people become more like yourself. You need to know why people act as they do. You need to offer an alternative, if only as a way of highlighting the flaws in our current system ��� hence the importance of the real utopias project and van Parijs���s call for a basic income. And you need to know how things might change: Wright���s theory of interstitial (pdf) transformation, for example, appeals to me.

Thirdly, analytical Marxism was a project about communication, about showing that Marxism and bourgeois social science can enhance each other. It���s very easy for lefties to stay in their intellectual ghetto, talk only among themselves and thereby develop a groupthink in which they are convinced of their own moral and intellectual superiority. Analytical Marxism is an antidote to this.

There is, though, something else which is not insignificant. It���s the personal character of at least several of the analytical Marxists. They are/were as far from the image of Marxists as spittle-flecked fanatics as you���ll get, combining cool heads with warm hearts and good humour (pdf): although Andrew Glyn was not quite an Analytical Marxist, he exemplified these qualities. The appalling fact that the left can be even remotely associated with antisemitism shows that such virtues are being lost. Which is why we so desperately need Analytical Marxism.

Another thing: what needs cleansing of bullshit is not just Marxism but also conventional economics which relies so much upon obscurantist or nonsense concepts such as aggregate production functions (pdf), representative agents, output gaps. LM curves and natural rates of interest.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers