Chris Dillow's Blog, page 30

June 28, 2019

The Tories' imaginary world

Sometimes, the Tories offer us a glimpse into their psychology. So it was yesterday when Sarah Vine tweeted:

Watching the #RestaurantMakesMistakes and astonished to learn that people with dementia struggle to get benefits. Is this true? And if so, how is this not a national scandal?

What she���s expressing here is the cognitive dissonance that her own party���s policies actually have nasty effects upon real people. Her consternation arises from the fact that, for many Tories, this is not supposed to happen. Many of them, I suspect, are not actually evil but rather guilty of a recklessness that comes from a particular conception of politics ��� a conception which sees it as a game of positioning, and of pandering to the imagined world of the Daily Mail. Politics is a post-modern activity in which words and appearances are everything and consequences and reality are nothing.

So for example:

- Benefit sanctions are supposed to crack down on cheats and malingerers, not real, deserving people. It is only when these appear on TV that the illusion ��� and it has been just that for years ��� is broken.

- The ���hostile environment��� policy was meant to remove illegal immigrants rather than members of the Windrush generation who are, remember, 100% British.

- Austerity was intended to establish prudent control of the nation���s finances. The fact that it has killed thousands is at best, a mere statistic, and at worst just another controversial claim.

- Brexit is about prioritizing a conception of national sovereignty over GDP. And GDP is a mere statistic, not the jobs and livelihoods of real people. What was so transgressive about Jeremy Hunt���s promise this week to shut down Titan Steel Wheels was that he broke this illusion, and linked what is supposed to be a mere abstraction to the lives of real people.

All of this is possible because for Tories ��� at least professional ones in the media-political Bubble - politics is a reified activity separate from ground truth. Robert Protherough and John Pick have described how modern management ���deals largely in symbols and abstractions...[with] little direct contact with the organization's workers, with the production of its goods or services, or with its customers.��� For Tories, politics is like that. It���s a cosy game in which nobody is supposed to get seriously hurt: the losers only leave to get well-paid sinecures from fund management companies.

Of course, if we had a functioning media, reality would intrude. But we don���t, so it often doesn���t. The truth is difficult and complicated and in John Humphrys��� revealing words ���a wee bit technical and I���m sure people are fed up to the back teeth of all this talk of stuff most of us don���t clearly understand.��� Bubble journalists are much happier covering the Tory leadership race than they are at analysing the real-world effects of actual Tory policies - a preference which generates sympathy for charlatans rather than experts. As Tom Mills says, the BBC ���will aim to fairly and accurately reflect the balance of opinion amongst elites.��� That can efface ground truth.

The upshot is that our media-political establishment conforms to what Kenneth Boulding said (pdf) back in 1966:

All organizational structures tend to produce false images in the decision-maker, and that the larger and more authoritarian the organization, the better the chance that its top decision-makers will be operating in purely imaginary worlds.

The problem which Ms Vine discovered this week, though, is that reality has a nasty tendency to intrude occasionally into the imaginary world.

June 26, 2019

The human factor

Could AI replace managers and even politicians? In their now-famous paper (pdf) describing how half of American jobs could be replaced by computers, Carl Frey and Michael Osborne say no: they estimate that chief executives, line managers and HR managers are among the 10% of occupations least likely to be computerized.

From the perspective of neoclassical economics, this is weird. It pretends that the job of bosses is to maximize profits, given a production function and prices of inputs. This is a constrained optimization problem which can easily be done by a computer.

Similarly, if you believe, Sunstein-stylee, that policy-making is a technocratic function of choosing optimal fiscal or monetary policy or the right choice architecture, the job can be delegated to computers, which have the benefit of being immune ��� in principle ��� to cognitive biases.

Which poses the question: what is it about bosses and politicians that make their jobs so unlikely to be replaced by tech? There are, I suspect, four things.

One is that the choice of what technology to adopt is not merely a matter of objective efficiency. It is also about power. In his excellent new book The Technology Trap, Frey describe how pre-industrial governments often forbade the use of labour-saving techniques, fearing they would cause a backlash and disrupt established hierarchies. And Joel Mokyr has written:

Resistance to technological change is not limited to labour unions and Olsonian lobbies defending their turf and skills against the inexorable obsolescence that new techniques will bring about. In a centralized bureaucracy there is a built-in tendency for conservatism. Sometimes the motives of technophobes are purely conservative in the standard sense of the word. This is equally true for corporate and government bureaucracies, and cases in which corporations, presumably trying to maximize profits, resisted innovations are legend. (The Gifts of Athena, p238)

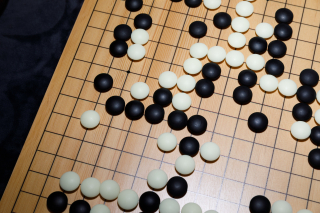

A second problem is that knowledge is not necessarily codifiable. AI works where all possible options can in principle be listed. Alphazero, for example, learned chess and Go by being programmed with the laws of the games and then playing millions of games against itself. In other contexts, such an approach doesn���t apply, and not just because what we are trying to achieve is sometimes not as simple or articulable as winning a game.

In many contexts there are what Donald Rumsfeld called unknown knowns ��� things we don���t know that we know. Tacit knowledge ��� hunches, gut feelings, things we have forgotten that we knew ��� matters. One reason why management is not merely a constrained optimization task is that even with given technology, good managers can tweak the production possibility curve outwards (pdf) by incremental improvements based upon hunches. Maybe brute force algorithms can replicate all these possible hunches and find the optimal one. But this is most easily done where the environment can be completely described ��� which is true of chess but not the real world.

There���s something else. An algorithm is, by definition, a set of rules. Sometimes, though, we succeed by breaking rules. For Israel Kirzner, this is in fact the very essence of entrepreneurship:

The Schumpeterian entrepreneur does not passively operate in a given world, he creates a world different from which he finds. He introduces hitherto undreamt of products, he pioneers hitherto unthought of methods of production, he opens up a new market in hitherto undiscovered territory.

Entrepreneurship, he says, ���is the process of discovering new knowledge and possibilities that no one has either previously imagined or noticed."

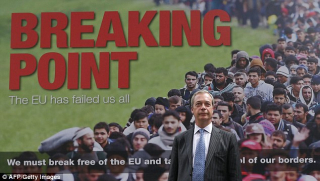

Herein lies one reason why AI can���t replace politicians. The success of Trump, Farage and Johnson has come from breaking conventions, be it the idea that leaders should conform to a particular ideal of good character, or that policies be evidence-based and compatible with the interests of business and the median voter. As Will Davies says:

Come November this year, Farage, Johnson and their allies may well have achieved a far greater disruption of the political and economic status quo than Thatcher or Blair ever managed, with a smaller popular mandate and far less effort. They don���t need think tanks, policy breakfasts, the CBI or party discipline. They don���t even need ideas. All they have to do, in pursuit of their goal, is to carry on being themselves.

There���s one final thing. Even if algorithms weren���t racist, they���d be only indifferent managers for one other reason. Sometimes, we want the human touch ��� the arm round the shoulder, the jolly-up, or the understanding that we���re having an off day.

It���s for a similar reason that AI will, I suspect, never write great music. Yes, it can produce passable if derivative tunes. But it has not yet given us truly original songs or insightful lyrics, nor what great music gives us, the sense of one soul speaking to another.

The same thing applies in journalism. AI can, in a fashion write news stories: these follow articulable rule. But it cannot (yet) produce marketable opinion columns: readers want the prejudices, biases and errors that only humans can provide.

What they also want are stories, even, or especially, if they are nonsense. We���ve good evidence ��� corroborated by the fact that so many of them recommended Woodford���s funds ��� that financial advice is poor. And yet robo-advisors have not expanded as much as they should. A big reason for this is that people don���t want to believe that simple rules work (such as buy cheap tracker funds). They want narratives and great investors they can trust. Only humans offer these.

And this is why AI cannot replace politicians. We prefer bad decisions taken by humans to good ones taken by machines. As Ben Jackson says:

Much of our politics today revolves around the perception that decisions are being taken elsewhere, whether in Westminster, Brussels or Washington. Passing off the work of decision-making to the ultimate aloof elite, a computer, is not a serious way of confronting this issue. Sometimes it���s important to decide things for ourselves, and to feel like we���re deciding, even if we often go astray.

What I���m driving at here is not merely a version of Moravec���s paradox. Nor is it a story about computers, especially as we might be on the verge of an era of super-powerful ones. Instead, my point is about the nature of power and decision-making. These are not merely technocratic algorithmic processes but are instead essentially and inherently human. Which is what conventional neoclassical economics has traditionally under-estimated.

June 21, 2019

The recrudescence of zero-sum thinking

President Trump believes we live in a zero-sum world in which one country���s gain is another���s loss. This is evident in his reaction to Mario Draghi���s comment this week that additional monetary stimulus will be needed if euro zone inflation doesn���t rise. Trump tweeted:

Mario Draghi just announced more stimulus could come, which immediately dropped the Euro against the Dollar, making it unfairly easier for them to compete against the USA. They have been getting away with this for years, along with China and others.

Adding that this is ���very unfair to the United States!���

This, of course, is bollocks. The US would actually gain from monetary stimulus to the extent that it strengthens the euro zone economy, thus allowing US firms to sell more to it: exports are more sensitive to demand than they are to exchange rates. What���s more, insofar as expectations of low interest rates cause investors to reach for yield and buy shares they are likely to also buy some US equities thereby giving Americans the benefits of a positive wealth effect and lower cost of capital. Sure enough, the S&P did indeed rise after Draghi���s speech. Trump tweeted that the index hit an all-time high this week, but failed to connect this fact and Draghi���s words.

Yes, Draghi deserves criticism. But it is for not responding soon enough to the weak economy and low inflation rather than for belatedly talking of doing so.

This is not the only example of Trump���s zero-sum ���thinking���. He also recently tweeted that:

The United States has been losing, for many years, 600 to 800 Billion Dollars a year on Trade. With China we lose 500 Billion Dollars.

You don���t need me to tell you that this is also bollocks. It is like me complaining that I lose money by my trading with Lidl. I don���t, of course. I merely exchange goods for money ��� which is exactly what US citizens with China are doing. Free exchange benefits both buyer and seller. It���s positive sum. In believing otherwise, Trump is expressing the pre-Smithian mercantilist idea, that wealth consists in piling up money by running a trade surplus, rather than in the expansion of consumption opportunities and increased productivity that comes from trade.

Everybody who has even the foggiest notion of economics can see that Trump is spouting mindless drivel: you don���t need to be a devout free-marketeer to see that trade usually benefits both parties.

Which poses the question: how can such nonsense even be entertained?

It���s here that we Marxists are alive to a fact that centrists and rightists sometimes neglect ��� that ideas have a basis in real material conditions. It is surely no accident that Trumpian zero-sum thinking became accepted among many voters after years of economic stagnation: even after their recent rise, median real household incomes are now only 2.2% above 1999���s levels. If the typical person���s income is flat-lining, he will eventually be willing to believe that one person���s gain is another���s loss. As Ben Friedman argued in a 2006 book which has been vindicated by subsequent events, economic stagnation breeds intolerance.

It���s not sufficient for those who support rational economics and an open society to decry Trump���s gibberish. If they are to triumph, such values require a society which delivers the goods for most voters. Much of the ruling class in both the UK and US neglected this fact before 2016, and we are all paying the price of their failure.

Another thing: this is not to say that there are no zero-sum processes in economics. It's quite possible that the increased wealth, power and incomes of the ultra-rich have come at the expense of everybody else. Despite his fondness for zero-sum thinking, however, Mr Trump never mentions this.

June 16, 2019

New Labour: success and failure

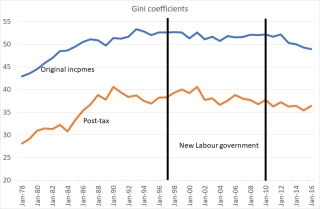

Did New Labour really ignore inequality? Responding to Corbyn���s claims that successive governments have neglected it for decades, Blair replies that New Labour ���made the UK more equal, more fair and more socially mobile.���

Both men, I think, are partially right.

Blair is correct to say that New Labour massively increased spending on public services and reduced child and pensioner poverty.

However, overall inequality did not change much under New Labour despite that fall in poverty. One reason for this is that as Robert Joyce and Luke Sibieta at the IFS have pointed out (pdf), their tax and benefit reforms ���had relatively little net impact on the top half of the income distribution���. Another is that pre-tax inequality rose in one important respect at least: the share of pre-tax incomes going to the top 1% rose from 10% to 12% between 1997 and 2007, before falling back as a result of the banking crisis.

It is in this last fact, I think, that New Labour���s failure lies, and where Corbyn has a point. Blair and Brown were far too managerialist, and too deferential to bosses: this much was evident not just in Brown���s lauding of them as wealth creators and courageous leaders but in his inviting the likes of Derek Wanless, David Freud and James Crosby to conduct policy reviews. Bosses, New Labour thought, were trusted experts.

In this respect, New Labour was indeed neoliberal. And this had at least three big costs.

One is that the importing of crude managerialism into the public sector failed to raise productivity: the ONS says this flat-lined (pdf) under New Labour. Yes, the public services improved. But this was simply because the government threw money at them. This made the health of the public sector dangerously dependent upon that of the private sector.

The second is that it meant that New Labour under-appreciated the many pathways through which the excessive wealth and power of the top 1% can worsen economic performance.

Thirdly, it fostered the belief that private sector companies could run themselves tolerably well if left alone. The banking crisis, however, revealed this to be a fiction.

That said, it is a little harsh of Blair���s critiques to blame a lack of banking regulation for the economic crisis. For one thing, the crisis was not due mainly to rising domestic debt. The banks that failed in 2007-08 did not, for the most part, do so because their loans turned bad. Instead, the main failures were due to terrible take-over decisions, such as RBS���s buying of ABN Amro, or because they relied upon wholesale funding which dried up in 2007: this was Northern Rock���s problem. Credit controls would probably not have prevented these failures.

And for another, the crisis was global. It would have hit the UK even if we���d had tighter regulation. In fact, in 2009 UK GDP fell only slightly more than the OECD average (4.2% against 3.4%) and it fell less than it did in Germany and Sweden, whose economies are often held up as models of what the UK should be. No reasonable policies could have insulated us from the global financial crisis.

From this perspective, it is absurd to blame New Labour for the subsequent austerity (except to the extent that we should blame it for losing the 2010 general election). We���d have had a deep recession in 2009 whatever the government would have done, and this would have greatly increased government borrowing thereby giving the Tories and the media the chance to complain about Labour profligacy. Austerity is the fault of the Tories and Lib Dems, nobody else.

New Labour had its faults, many of which are more obvious with hindsight than they were at the time, and the left is wholly correct to want to move on from its economic policies which are now out-of-date. But these facts should not detract from another fact ��� that Labour did indeed do much to reduce poverty.

May 28, 2019

The Johnson puzzle

One of the puzzles of our time is why Boris Johnson is considered ��� not just by Tory members but by much of the media - to be a credible contender for Prime Minister when many of us regard him as a oafish buffoon, serial liar and associate of criminals. One answer to this paradox, I suspect, lies in the concept of ambiguity aversion.

This is the notion that people much prefer the familiar to the unknown, and known risks to unknown ones: they strongly prefer (pdf) 50-50 bets to ones on unknown proportions. Such ambiguity aversion explains a lot of behaviour in financial markets, ranging from the home bias in equity portfolios to the US���s ���exorbitant privilege.���

It also, though, explains political attitudes.

The thing is, the Tory party is for many people the familiar option; it is after all the natural party of government. When Cameron threatened ���chaos with Ed Miliband��� and May promised ���strong and stable government��� they were appealing to the presumption, that the Tories offered familiarity and comfort whilst Labour offered uncertainty ��� something people hate. For this reason, turmoil in the Tory party is "drama" whereas that in the Labour party is "chaos".

It���s not just Tory supporters for whom the Tories are the known safe prospect. The same���s true for much of the media.

One reason for this is class. Most top journalists went to private schools. They therefore regard Johnson as ���one of us���. For the same reason, they regard a public school-educated commodities broker with suspected links to Russian oligarchs and who doesn���t listen to music or watch TV as a ���man of the people.���

It���s not just personal homophily that makes the Tories the familiar option, though. Being privately educated inculcates people into shared presumptions such as about what counts as ���educated��� (classical references do but numeracy doesn't); what matters (economics doesn���t) and who is or is not part of ���the country���.

Much of the media and the Tory party have other things in common, though. One is a shared conception of what politics is ��� an Oxford Union-style game iof jockeying for position. The BBC, like much of the media, is obviously happier covering the Tory leadership race than it is covering substantial policy which ends up, in Humphrys��� words. ���all getting a wee bit technical and I���m sure people are fed up to the back teeth of all this talk of stuff most of us don���t clearly understand.��� It thus sees Johnson as a player of a game it understands, whilst it ruthlessly othered technocrats such as Ed Balls or Ed Miliband*. In the same way, the failure to see that politics can be a project of building mass movements has lent the BBC a bias against Corbynites and other activists.

Also, the media prefers human interest stories to theories of emergence, in which social outcomes for good or bad are the product of human behaviour but not design**. This too lends a bias towards seeing politics as a clash of characters rather than as a more complex process.

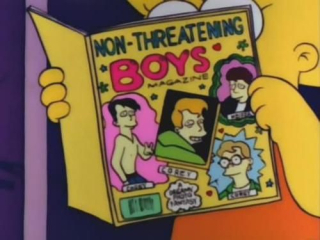

The Tory party, therefore, is seen ��� not just by its own members but by most of the media, including the BBC ��� as a cosy familiar option. From this perspective, Johnson offers it the same thing that Lisa Simpson gets from non-threatening boys ��� a frisson of excitement in what is actually a safe environment. Tories and the media know that whatever else Johnson does he will not do anything really dangerous such as put an extra penny on the top rate of tax. Johnson���s (and Farage���s) many media appearances reinforce this impression. As Alan Bennett wrote, they make them seem ���human and harmless and that their opinions are not really as pernicious as their opponents pretend.���

It is only those of us from other backgrounds and perspectives who see them otherwise. It is surely no accident that the only times Johnson has been seriously challenged by the BBC has been in interviews with Eddie Mair. He might seem a harmless joker to media insiders, but to the son of a lorry driver he appears altogether more sinister.

In this sense, the mirror image of Johnson is Tony Blair. Whereas Johnson is a slightly thrilling personality from a familiar organization, Blair in the 90s offered a safe and comforting front for what was an unfamiliar and thus unsettling party.

Now, I���m not making a partisan point here. I could say much the same for many metropolitan and academic leftists: for, them, Che Guevara, Hugo Chavez or even various terrorists have served the same function Johnson serves for Tories and the much of the MSM.

Instead, I���m complaining about a tendency for everybody to inhabit bubbles in which they are unaware of the partiality of their own perspective. I suspect this is an increasing problem, caused by decline of two otherwise different characters: the aristocratic Tory who crouched in foxholes with working class men; and the upwardly mobile working class man who enters posher circles. For me personally, the most attractive of the Tory candidates is the (yes, Etonian) Rory Stewart whose career suggests a willingness to step out of a comfort zone of his own background and presumptions.

Such a failure to see that one is in a bubble is perhaps forgivable for those on both the left and right. Whether it is quite so forgivable for the BBC, which pretends to be impartial, is another question.

* Some Tories are victims of this othering: when David Willetts was called ���two brains��� it wasn���t an unalloyed compliment.

** For example, the media took Osborne at his word when he claimed to be trying to control the public finances, oblivious to the most basic concept of emergence, the paradox of thrift.

May 23, 2019

The Tories' structural weakness

As a lefty, the disarray in the Tory party provides a lovely schadenfreudic coincidence ��� that the same intellectual failing that causes the party���s bad government also causes it to elect unsuitable leaders.

This failing is an inability to see failures of collective action ��� to see that what is rational for each individual is often bad for everybody.

An obvious example of this came in 2012 when Cameron advised people to top up their petrol tanks in advance of a strike by lorry drivers. He failed to see that whilst this might have been sensible for any individual, its aggregate result was to trigger panic buying and fuel shortages.

There are, though, other examples. Collective action problems mean that public goods such as infrastructure are under-supplied and public bads such as pollution are over-supplied: each individual thinks it won���t make any difference to the climate if he gets on a plane, with the result that too many do so. If everybody ��� especially the government - tries to cut their borrowing the result is not lower debt but lower incomes for us all. Similarly, whilst you might be able to incentivize any one person to find work by cutting benefits, you cannot incentivize everybody this way: the result is just misery for those out of work. And we cannot rely upon shareholders to control company managers because the hard work of doing so is borne by the individual shareholder whilst the benefits are spread widely over all, with the result that we have inadequate corporate governance. And so on.

The point of politics is to solve collective action problems such as these. The Tory party has, however, under-rated the importance of such problems and so have given us austerity, economic stagnation and an inadequate response to the climate emergency,

Here, though, is the nice irony. The same blindness to collective action problems that caused the Tory party to wreck the economy is now causing it to destroy itself.

What I mean is that its choice of leader suffers the same problem. Each individual considering who should be leader thinks of his personal perspective: who personally do I find simpatico? Whose ideology is closest to mine? And, for MPs, who will give me a job?

These considerations of private gain, however, neglect the collective good (from Tories point of view) of the health of the party. What matters for the party is not that it has the leader closest to your own ideology, but that it has the right leader ��� that a round hole be filled by a round peg.

This is true in business. As Boris Groysberg and colleagues have shown (pdf) If a company needs a marketing man as CEO but hires an engineer, things go wrong. But if it needs a marketer and gets one, it does well.

And it���s true in politics too. For example, Churchill was a man of massive flaws. But in 1940 many of these faults, such as bombast and belligerence, became virtues. And other failings ��� such as his racism and ignorance of domestic economic and social matters ��� weren���t important. In 1940-45, Churchill was a round peg in a round hole. Before and after then, he was not.

Or consider Cameron. He was the right man to detoxify the Tory party in 2005. But the same overconfidence that led him to stand for leadership despite a lack of experience also caused him to call the Brexit referendum. What was a strength in 2005 was a catastrophic weakness in 2016. He stayed the same shape, but the hole changed.

Or consider May. One can imagine circumstances in which her stubbornness would be a strength ��� if the party had a good strategy which needed sticking to. But these are not the circumstances we���ve had recently. We���ve needed a negotiator ��� someone with intellectual flexibility and interpersonal skills. And May is wholly lacking such skills.

What matters, then, is the match between the requirements of the job of party leader, which vary from time to time, and the qualities of individual. Sometimes, as in Churchill���s case, the match is good: the man���s vices can either become strengths or be easily overlooked. What we have now, though, is a terrible match: May���s weaknesses are horribly exposed.

If Tory members and MPS consider only their private gain ��� ���who most agrees with me?��� ��� they���ll not ask who is the best match. It is only by accident then that they���ll elect the most suitable leader. And it���s a long time since this accident happened: the party���s last five leaders ��� Hague, Duncan-Smith, Howard, Cameron and May ��� have all left something to be desired.

But it was not always thus. Before 1965 Tory leaders were not elected but rather chosen by grandees. Because they were often old enough to have sloughed off ambition, such men put a higher weight upon the good of the party and less upon their private gain. They solved the collective action problem, and the Tory party was much stronger for it. The party has, however, now lost this solution. And the delightful irony is that the same blind spot that has caused it to wreck the country is now causing it to wreck itself.

May 17, 2019

How inequality makes us poorer

I welcome the Deaton report into inequality. I especially like its emphasis (pdf) upon the causes of inequality:

To understand whether inequality is a problem, we need to understand the sources of inequality, views of what is fair and the implications of inequality as well as the levels of inequality. Are present levels of inequalities due to well-deserved rewards or to unfair bargaining power, regulatory failure or political capture?

I fear, however, that there might be something missing here ��� the impact that inequality has upon economic performance.

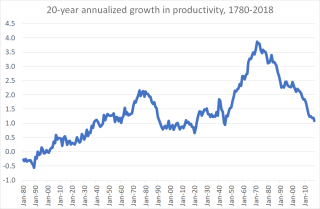

My chart shows the point. It shows the 20-year annualized rate of growth in GDP per worker-hour. It���s clear that this was much stronger during the relatively egalitarian period from 1945 to the mid-70s than it was before or since, when inequality was higher.

This might, of course, be coincidence: maybe WWII caused both a backlog of investment and innovation which allowed a subsequent growth spurt and a desire for greater equality.

Or it might not. This is not the only evidence for the possibility that inequality is bad for growth. Roland Benabou gave the example (pdf) of how egalitarian South Korea has done much better than the unequal Philippines. And IMF researchers have found (pdf) a ���strong negative relation��� between inequality and the rate and duration of subsequent growth spells across 153 countries between 1960 and 2010.

Correlations, of course, are only suggestive. They pose the question: what is the mechanism whereby inequality might reduce growth? Here are eight possibilities:

1. Inequality encourages the rich to invest not innovation but in what Sam Bowles calls ���guard labour��� (pdf) ��� means of entrenching their privilege and power. This might involve restrictive copyright laws, ways of overseeing and controlling workers, or the corporate rent-seeking and lobbying that has led to what Brink Lindsey and Steven Teles call the ���captured economy.��� An especially costly form of this rent-seeking was banks��� lobbying for a ���too big to fail��� subsidy. This encouraged over-expansion of the banking system and the subsequent crisis, which has had a massively adverse effect upon economic growth.

2. Unequal corporate hierarchies ��� what Jeffrey Nielsen calls rank-based organizations - can demotivate junior employees. One study of Italian football teams, for example, has found that ���high pay dispersion has a detrimental impact on team performance.��� That���s consistent with a study of Bundesliga and NBA teams by Benno Torgler and colleagues which found that ���positional concerns and envy reduce individual performance.���

3. ���Economic inequality leads to less trust��� say (pdf) Eric Uslaner and Mitchell Brown. And we���ve good evidence that less trust means less growth. One reason for this is simply that if people don���t trust each other they���ll not enter into transactions where there���s a risk of them being ripped off.

4. Inequality can prevent productivity-enhancing changes, as Sam Bowles has described. We have good evidence that coops can be more efficient than hierarchical ones, but the spread of them is prevented by credit constraints. Poverty reduces education levels by making it impossible to afford books, or encouraging bright but poor students to leave earlier than they should, and women and BAME people might avoid careers for which they are otherwise well-suited because of a lack of role models.

5. Inequality can cause the rich to be fearful of future redistribution or nationalization, which will make them loath to invest. National Grid is belly-aching, maybe rightly, that Labour���s plan to nationalize it will delay investment. But it should instead ask: why is Labour proposing such a thing, and why is it popular?

6. Inequalities of power ��� in the sense of workers��� voices being less heard than they were in the post-war period and trades unions becoming less powerful ��� have allowed governments to abandon the aim of truly full employment and given firms more ability to boost profits by suppressing wages and conditions. That has disincentivized investments in labour-saving technologies.

7. The high-powered incentives that generate inequality within companies can backfire. As Benabou and Tirole have shown (pdf), they encourage bosses to hit measured targets and neglect less measurable things that are nevertheless important for a firm���s success such as a healthy corporate culture. Or they might crowd out intrinsic motivations such as professional ethics. Big bank bonuses, for example, encouraged mis-selling and rigging markets rather than productive activities.

8. High management pay can entrench what Joel Mokyr calls the ���forces of conservatism��� which are antagonistic to technical progress. Reaping the full benefits of new technologies often requires organizational change. But why bother investing in this if you are doing very nicely thanks to the increased (pdf) market power of your firm? And if you have, or hope to have, a big salary from a corporate bureaucracy why should you set up a new company?

My point here is that what matters is not so much the level of inequality as the effect it has. And it might well be a pernicious one. If inequality has contributed to weaker growth, then it is very likely to have contributed to the rise of populism and to Brexit and the divisions with which both are associated. In this way, inequality does political damage too.

From this perspective, pointing out that the Gini coefficient has been flat for years (which is true if we ignore housing costs) is like saying that because the bus has stopped moving we need not care about the man who has been run over by it. It misses the main point.

May 14, 2019

Debating the far right

The far right has been defeated. Andrew Neil���s interview with Ben Shapiro and Andrew Marr���s with Nigel Farage have exposed both men as shifty, vacuous and evasive. Their support will therefore disappear. What took the might of the Red Army in 1941-45 has today been achieved by two ageing Scotchmen.

Or not. For one thing these episodes won���t weaken the far right���s resolve. Farage is playing the victim card. ���We are not just fighting the political class, but the BBC too��� he says. Sure, his opponents think his interview was a disaster but his sympathizers don���t: Andrew Lilico called it his ���best ever.��� Such reactions demonstrate the pervasiveness of asymmetric Bayesianism ��� that we interpret evidence to corroborate our priors.

If we���re being honest with ourselves, many of our political views ��� by no means just those on the right ��� were formed sub-rationally. And as Jonathan Swift said, ���reasoning will never make a Man correct an ill Opinion, which by Reasoning he never acquired." This is especially the case if the protagonists are debating in bad faith.

Now, many of you will object to this that whilst such interviews and debates might not persuade rightists themselves, they might help turn neutrals away from the movement. I���m not convinced, and not just because Marr and Neil are only watched by a handful of politics nerds.

One issue here is that defeating rightists in debate is like playing whack-a-mole; even if you knock one down, another pops up. It���s generally agreed that Nick Griffin made a fool of himself on Question Time back in 2009, and sure enough he has since fallen into deserved obscurity (although the BNP did increase its vote in the following year���s general election). But other far-right figures have replaced him, such as Stephen Yaxley-Lennon.

There���s an analogy here with snake-oil sellers. Even when reason and evidence did show that a particular product was inadequate, customers did not shun snake-oil generally. They simply switched to other sellers instead. As Werner Troesken showed in a fantastic paper (pdf), demand was unaffected by failure.

A second problem is that we���ve no good reason to believe that people are swayed by fact and reason alone. We know that huge numbers of voters are ignorant of basic facts, which makes them credulous about all sorts of daft ideas. We know too that they are swayed by things other than rational argument, such as looks (though in fairness these are unlikely to win Mr Farage much support). Rationality doesn���t just require intelligence. It needs immense self-discipline, which many of (not least me) just do not have ��� and in the case of politics, have neither the means nor incentive to acquire it.

Which means neutral observers ��� even assuming there to be such things ��� are prone to countless cognitive biases. A particularly dangerous one in this context is the mere exposure effect; the more we see or hear something, the more we like it. It���s possible (pdf) then that Andy Dawson is right: ���the blanket coverage [Farage and UKIP] have been afforded has directly led to the shifting of the political landscape in Britain.���

What matters here is not just Farage���s personal appearances on TV. It���s also what gets discussed. The more time the BBC devotes to the concerns of the right ��� ethno-nationalism, anti-���elitism���, Brexit and so on ��� the more normal people think such debates should be. And conversely, in crowding out other matters, such as the decade-long stagnation in productivity and real wages, these become fringe issues. The agenda matters. And merely debating with the right shifts the agenda onto their terms.

I fear, then, that the right will not be defeated by debate. We must instead pull out the roots of its support. It is surely no accident that right-wing populism has increased around the world at a time of economic stagnation. Reducing its support therefore requires an end to that stagnation. It won���t be done by talk alone.

May 9, 2019

On media influence

Not everything that stinks causes disease. Yes, there is plenty wrong with the press and BBC, but how much influence does it actually have?

I ask because of Simon���s recent post blaming the media for the sheer incompetence of this government. I���m not so sure about this. The press has always had a right-wing bias, but we haven���t always had a government as lousy as this one. This alone tells us that other factors are at work: mechanisms that select for fanatics and against competence have strengthened in recent years.

Equally, it would be stretching things to blame the media for the rise of coarse right-wing populism. The press has been fomenting this for decades: the Sun ran the headline ���Up Yours, Delors��� way back in 1990. But it is only in recent years that it has become so widespread. This tells us to look elsewhere for explanations ��� for example in increased (perceived) threats to old white male supremacy or to the psychological impact of economic stagnation. As Martin Wolf says, ���sharing out losses generated by a financial crisis, followed by the inevitably weak recovery, always creates public rage.���

What���s more, the cognitive biases research inspired by Kahneman and Tversky shows us that people are perfectly able to be idiots without reading the papers. Pro-capitalist ideology can emerge without their help.

And personally, I find blaming the press to be aesthetically displeasing: I fear it can sometimes come close to conspiracy theory, and under-rates the importance of emergence.

We also have empirical evidence from the US that the press doesn���t much matter. Matthew Gentzkow and colleagues used the opening and closing of daily newspapers to estimate effects on voting behaviour and found (pdf) ���no evidence that partisan newspapers affect party vote shares.��� One reason for this is that papers respond to readers��� ideologies (pdf), not vice versa.

But, but, but. There���s also evidence on the other side. Jonathan McDonald Ladd and Gabriel Lenz show that Sun readers were more likely (pdf) to vote Labour in 1997 than otherwise similar people who didn���t read the rag, implying that the Sun���s shift to supporting Labour in the 1997 election did shift votes. US evidence shows that the roll-out of Fox News boosted the Republican vote. One study has found (pdf) "quantitative and qualitative evidence that media coverage may have played a unique causal role in increasing support for UKIP," And the fact that young people are far more left-wing than oldsters ��� something which was not the case in the 80s ��� might be due in part to the fact that they don���t read the papers.

What���s more important for me, though, is perhaps the role of the press in shaping the agenda, in deciding what gets talked about: in this context is the constant drip, drip of stories that matters more than any individual one. Simon is right to say that media stories of Labour���s over-spending created a climate receptive to Tory claims that government borrowing was a big problem. The MPs��� expenses ���scandal��� helped to foster a distrust of parliamentarians*. And anti-immigrant stories in the papers might well help explain the otherwise curious fact that anti-migrant sentiment tends to be strongest in areas which have low immigration. When people can compare the evidence of their own eyes to newspaper stories, they disbelieve the latter, but when they can���t���

Of course, if the press puts some things onto the agenda it follows that others things are kept off it. Not least of these is the truth. The fact that people were ignorant of basic facts about the EU in 2016 and that Tory MPs needed a training session this year on what a customs union is both tell us that the media does a lousy job of informing people.

The facts, though, aren���t the only things avoided. In talking about Brexit, immigration, identity politics and so on, important questions get ignored ��� such as the causes of stagnant real wages or of inequality. Even well-meaning journalists, in their search for heroes and villains, tend to under-rate the importance of emergent social phenomena. One of the BBC���s greatest failings is perhaps a tendency to take its agenda from the press, thereby exacerbating the bias against understanding.

Net, then, I suspect our media is indeed a problem, though not the only one. Which means that one task of the left - a task it has for years failed at - is to change what we talk about.

* The fact that some of the most imaginative writing in English literature has sometimes been in journalists��� own expenses claims was curiously overlooked in that affair.

May 3, 2019

Yes, ownership matters

I welcome the creation of the Common Wealth think tank, which aims to promote ���deep shifts in property relations and ownership.��� There���s one possible preconception about this project which must be debunked, however. This is that it is hippy-dippy yogurt-weaving idealism. It���s not. The question of who should own and control companies is bog-standard mainstream economics: at least three Nobel prizes ��� to Hart, Williamson and Coase ��� have gone to economists working on this and related issues.

And in fact, stock markets themselves are calling into question the feasibility of existing ownership structures. In the UK the number of companies listed on the main market has dropped from 1747 to 1156 since the start of the century, a trend which matches those in the US and Europe. And as Kathleen Kahle and Rene Stulz show, those that are listed are bigger and older than they were then and are less profitable and hold more cash.

One big reason for this is that dispersed share ownership does not adequately control management. This is partly because of a free-rider problem. With hundreds of outside shareholders each one has an incentive to piggy-back off of others��� efforts to oversee management. Everybody therefore hopes that somebody else will be the active investor, with the result that nobody is.

As Michael Jensen pointed out in a famous paper in 1989 this is fine for companies with lots of potentially profitable projects who need to raise money to finance them: it���s no disaster if poor oversight of managers causes them to select projects with a 20 rather than 30% return on capital. But, he said, it is a problem for companies facing slow growth or which have lots of cash and few good investment opportunities. And in a world of secular stagnation there are more of these. For them, dispersed ownership is inappropriate ��� which is why we see fewer companies listed on western stock markets.

This problem can often be solved by more concentrated ownership. But there���s another issue here. To see it, ask: who should control an asset? In theory, it should be the one who stands to lose most if the asset falls in value and gain most if it increases. This person is the one who has the strongest incentive to maximize the asset���s value. Traditionally, this person has been the owner ��� be it the shareholder or direct owner. This, it has been thought, is because other stakeholders such as workers, bond-holders, banks or suppliers are protected by contract, leaving the owner as the residual claimant.

This thinking, though, is wrong. As Colin Mayer says (pdf):

Contracts are very restricted���Shareholders are not therefore by any means the only party exposed to the misfortunes of corporations and the more that we strengthen the rights and powers of shareholders, the more we threaten the interests of others.

There are at least four other actors who are residual claimants:

- As we saw with the collapse of City Link or Carillion, subcontractors often get shafted when a firm fails whilst owners and directors can extract large ���consultancy fees���.

- Workers who have invested job-specific human capital in a company cannot get so good a job if the company fails. As Oliver Hart has written, ���a party with an important investment or important human capital should have ownership rights.��� (Firms, Contracts and Financial Structure, p48)

- The failure of large firms, or those that are key hubs in a network, can cause deep recessions, as we saw in 2008. Pretty much all of us suffered from the collapse of the banks. And as Edward I ��� a man not noted for socialist sympathies ��� said "common dangers should be met by measures agreed upon in common.*"

- For companies that are contributing to climate change, future generations are in effect a residual claimant: they are at risk from the firms��� actions.

All this raises some questions.

First, could these parties exposed to corporate risks be protected by changes in regulation, contracts or carbon taxes? We know that they have not been so far. And I fear that the power of capital to block such changes means they won���t be.

Secondly, shouldn���t market forces select against bad companies? In part, they don���t simply because the forces of competition don���t grind so finely. The fact that there is a long tail (pdf) of inefficient companies in all countries shows that bad management isn���t strongly selected against. And even when it is, the process is disruptive of people���s lives so the residual claimancy problem remains.

Thirdly, can the market alone achieve efficient changes in ownership? The fact of de-equitization suggests that sometimes it does. There are, though, at least two issues here. One is simply that there are credit constraints: the best owner of a firm might not be able to raise finance the buy it. A second is that new forms of ownership might require legal change. The limited company was we know it was created by two acts of parliament in 1844 and 1855. (The notion that free market capitalism is somehow natural and emerged without state intervention is a fiction.) Other new forms might require such change, or at least government encouragement, perhaps through use of its procurement activities as is happening in Preston.

Fourthly, who should own companies? The answer, as in most economic questions, is: it depends. In some cases, it should be workers. Where these have serious investments in the firm, in the form of job-specific human capital or a lack of outside options, they have sufficient skin in the game to warrant ownership or control. They also often have dispersed fragmentary knowledge about corporate performance and how to improve it that managers cocooned in the C-suite lack: worker control can be a solution to Hayek���s knowledge problem. This is especially the case if such firms don���t need to raise lots of equity finance. For other firms, Mayer has suggested ownership by a public benefit company, which ensures that firms fulfill a stated public purpose beyond mere maximization of profits: as John Kay has shown, the latter is better done as a by-product of other aims, such as producing great goods.

Fifthly, if all this is the case, why has ownership been off the political agenda for so long? One reason is that since about the 1930s Labour thought that it could achieve social democratic objectives without challenging existing ownership structures ��� by using macro policy, taxation, regulation or strong unions. The collapse of post-war Keynesianism in the 70s, and weak growth in our neoliberal order since, however, suggests that this belief was wrong. Maybe, therefore, ownership does matter ��� and in some cases at least, it might be in the wrong hands. And this is to consider the question without even raising the matter of justice and equality.

* I suppose the mood of the times requires that I note that he was a vicious anti-Semite.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers