Chris Dillow's Blog, page 29

July 25, 2019

Centrists against evidence

In an excellent piece, Martin Sandbu says the state has more power to tax companies than we had thought, and calls for us to move away from ���learnt helplessness in the face of inequality and stagnation���. What we need, he says, is ���centrist radicalism���:

That requires centrist politicians to move out of their incrementalist comfort zone and pursue policies that measure up to the scale of our problems. The challenges include the overhanging burden of past mismanaged economic crises and looming climate change disruption in the future. Populist snake oil from the right or the left will not solve these. Neither will centrist tweaks.

This is a noble call. But one, I fear, that will fall in deaf ears.

I say this because of a big paradox within centrism ��� that whilst it claims to be pragmatic and evidence-based, it in fact systematically ignores some of the strongest evidence of all.

In a paper (pdf) last year, Chris Leslie boasted that centrists believe in ���evidence not ideology��� and in ���choosing an evidence-based rather than ideologically-driven approach to the world.���

However, the biggest evidence we���ve had in recent years was the financial crisis of 2008 and subsequent decade-long (and counting) flatlining in productivity and real wages. This is powerful evidence that, left to itself, capitalism generates recession and stagnation. To fight these tendencies, the state must do more than merely provide a stable policy framework and light regulation as New Labour did.

Centrists, however, show no sign of acknowledging this. Leslie wrote that the crisis ���fuelled cynicism about government and politicians���, but made no mention that it might ��� just might ��� require a rethinking of the relationship between the state and capitalism.

This was no idiosyncratic oversight. In an attack on Corbyn for taking Labour ���out of the mainstream��� Ian Austin ignored the possibility that the crisis requires Labour to do what Blair did in the 90s ��� to adapt policies to the new environment.

Similarly in its launch statement (pdf) earlier this year the Independent Group made no mention of austerity or stagnation but did speak of government���s ���responsibility to ensure the sound stewardship of taxpayer���s money���, apparently oblivious to the evidence of negative real bond yields.

This trend continued this week. Jo Swinson justly attacked the ���harsh, hostile politics��� of populism in which liberal values such as openness and freedom are ���are under attack.��� She did not, however, address the question: is it really just a coincidence that intolerant politics should arise after economic stagnation? The answer is, of course, that it���s not. Ms Swinson, however, ignored the vast evidence accumulated by Ben Friedman which shows that stagnation fuels illiberalism.

Such blindness to evidence isn���t confined to British centrists. Aaron Timms has complained that Cass Sunstein has ignored lots of things we���ve learned since 2008:

We now know that in the arena of environmental regulation, nudges decrease support for the more ambitious policies that might be needed to avert an ecological catastrophe. We know that a technocratic, cost-benefit-focused approach to government works to the detriment of visionary change. We know that the old neoliberal binary���state bad, market good���is simplistic and no longer squares with a reality in which many of our greatest tyrannies emerge from a rapacious and meekly regulated private sector. Most importantly we know that the Obama presidency, the guiding hope to so many market-friendly liberals, ended with rising inequality, stalled social mobility, a spiraling climate disaster, and the Trumpian revolt against expertise.

There���s a pattern here. Centrists��� claim to be pragmatic and evidence-based is just sanctimonious self-delusion. Their views, like those of the rest of us ��� including us Marxists - are an admixture of ideology-led and evidence-led. The difference lies in which evidence we use and which we ignore.

Of course, it is possible that a centrism will emerge that does learn from the past and have robust answers to stagnation, crisis and inequality. So far, though, there is less evidence that centrists are doing this than that the left is learning a new economics from the past failures of socialism. If centrists want me to think of them as a serious alternative to Corbyn, this will have to change.

July 24, 2019

The Technology Trap: a review

The historian Suetonius wrote that, when approached by a man offering a cheap technology for transporting heavy columns to Rome the emperor Vespasian refused to use the device for fear it would displace workers. ���How will it be possible for me to feed the populace?��� he asked. The fear that new technology will destroy jobs is, therefore, an ancient one.

This is the theme of Carl Benedikt Frey���s The Technology Trap. Although Dr Frey is best known for his work with Michael Osborne predicting (pdf) that new technologies threaten millions of jobs, his book is not an exercise in futurology. Most of it is a fascinating history of technical change.

There are, he says ��� echoing Acemoglu and Restrepo - two main types of technical change. Some enable workers to do more, making them more productive and creating new work. Others, though, simply replace labour. Frey argues that much of pre-industrial technical change was labour-replacing, and was often suppressed by states fearful of the unrest that would cause: Elizabeth I refused a patent for William Lee���s knitting machine in 1589 on these grounds. And, he argues, the early decades of the industrial revolution was also an era of labour-replacing techniques ��� hence the ���Engels pause���, years of stagnant wages. A big reason for the industrial revolution, Frey shows, is that the British state shifted from supressing technical change to using coercion to enable such change: many Luddites were hanged. Frey nicely rebuts the silly just-so stories of some right-libertarians who tend to see capitalism as natural.

It was only later in the industrial revolution that technical change actually created jobs, and goodish ones even for unskilled work. In the long sweep of history, however, this sort of change ��� and the improved living conditions for the masses it brought ��� was unusual. This fits with Walter Scheidel���s work from a very different perspective, which has argued that periods of increased equality are historically very rare.

From this perspective, the labour-replacing changes that Frey fears will come from AI and robotics are in a sense a reversion to the historic norm. As futurology one might quibble with that; people are bad at predicting technical change. But turn the question around: how likely is it that new technologies will provide good jobs for unskilled men of the sort we saw in the first half of the 20th century?

So, where might we argue with Frey���s analysis? I agree with John Thornhill that his policy suggestions (around helping workers adapt (via education, changes in zoning laws and suchlike) are weak, but this is common in many books analysing our new times.

Instead, I suspect Diane Coyle is right to argue that Frey treats technical change as exogenous when in fact it isn���t. For example, the distinction between labour-replacing and labour-enabling technical change, whilst insightful, distracts us from another type ��� the sort that enables capitalist exploitation such as the power-biased technical change discussed by Skott and Guy. We should ask: if we have greater worker ownership, what sort of technical change would we see? Mightn���t it be more labour-enabling?

In not seeing such change an endogenous, Frey under-estimates our current paradox ��� that (to paraphrase Solow) robots are everywhere except in the data. The key facts of recent years are that unemployment is at a 45-year low; that business investment has flatlined for years; and that productivity is stagnating. The data suggest that people are stealing robots��� jobs, not vice versa.

Frey is right to say that such stagnation is common in the early years of new technologies. But I suspect this isn���t the only explanation. It���s also the case that there are big barriers to robotization such as: firms��� fears that new technologies will be out-competed by future cheaper tech; that firms with intangible assets struggle to raise finance for lack of collateral; that low wages and a quiescent workforce mean there���s little need to invest in labour-saving techniques; or that the tech crash and financial crisis have near-permanently depressed animal spirits.

Frey���s work, however, poses two deep issues which we should all think about. One is: are sensible economists right to want supply-side policies that boost productivity? If we get these, mightn���t we open the Pandora���s box that Frey fears, of significant labour-displacing investment? Is good macro policy aimed at maintaining full employment really sufficient safeguard here?

The other is that technology changes culture. The jobs at threat from AI are, mostly, those that require us to follow algorithms: robots do that better than us. Humans��� comparative advantage lies instead in creativity and soft skills. Should we do more to foster these, by changing educational priorities? How would culture, society and humans change if much of what we now think of as skilled professional work is instead done by machines?

July 21, 2019

Centrists' failure

Mine and Simon���s claim that Corbyn is the lesser of two evils has had a lot of pushback. Some say Corbyn is more antisemitic than we think, others that we do indeed have other choices*. All this, however, raises the question: how have we gotten into the position where the choices of future Prime Minster are so poor? The worse you think Corbyn is, the more force this question has.

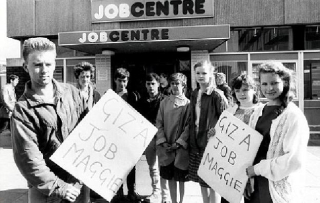

The answer, to a large extent, is that centrists have failed. They had the ball - New Labour and the LibDems were in office for 18 years ��� and they dropped it. Johnson and Corbyn have risen as centrism has fallen. Centrists show an astounding lack of self-awareness about their own abject failure.

Corbyn is popular ��� insofar as he is ��� not because he is a political genius (he���s not) nor because many of us have become antisemites or have lost our minds. His popularity ��� especially with young graduates ��� rests upon material economic conditions. The degradation of professional occupations and huge gap between the top 1% and others have radicalized young people in erstwhile middle-class jobs; financialization has made housing unaffordable for youngsters; and a decade of stagnant real wages ��� the product of inequality and the financial crisis - has increased demands for change.

There���s nothing inevitable about young people being radical: in the 1987 election the Tories won the 25-34 year-old vote and only narrowly lost among 18-24 year-olds. Young people's support for Corbyn is because capitalism as it currently exists has failed them - and it has done so because centrists have let it.

The same can be said of Brexit. Austerity, at the margin, tipped the balance against Remainers. The marginal Brexit voter wasn���t some gammon who thinks Dambusters should the role model for our relations with the EU. It is someone who was cheesed off with living in a run-down area and being ignored by the (centrist) elite.

Centrists are oblivious to all this. The tiggers or cukkers or whatever they call themselves today have no awareness of the reality of capitalist stagnation, let alone have an answer to it. Corbyn became Labour leader because his rivals (with the partial exception of Liz Kendall) had no worthwhile material programme to offer. The LibDems acquiesced in the austerity that led to both Brexit and Corbynism. And the centre right merely wags its finger at voters to tell them they got it wrong, whilst showing no awareness that its own policies are responsible for Brexit, and no appreciation that the slogan ���take back control��� had so much power for so many voters.

Leftists often accuse centrists of being Blairite. This is a slur upon Blair. His genius was to recognise in the 1990s that the world had changed and that new policies were needed for new times. Centrists today are innocent of such insight. They are stuck in a 1990s timewarp. It is Corbyn who is the true heir to Blair, as he sees ��� albeit perhaps in the same way that a stuck clock is right twice a day ��� that our times require new policies. He at least offers a faint shadow of a glimmer of slim hope of an alternative to the neoliberal financialization that got us into this mess. Centrists offer jack-shit.

Even the IMF now acknowledges that inequality is a menace to economies. Whilst some individual centrists get this (I'm looking at you Paddy and Tony) centrist politicians do not.

Now, some might object here that aspects of the LibDems 2017 manifesto were more redistributive that Labour���s, which was insufficiently hostile to the benefit freeze. But LibDem manifestos are a soft currency: the 2010 one said nothing about trebling tuition fees or supporting austerity, benefit cuts and the hostile environment policy. Redistribution is part of the soul of the Labour left; the same cannot be said for the LibDems. As I said in another context, if you���ve got yourself a reputation for laziness you need to work doubly hard if you are to lose it. The LibDems are not doing so.

You might also object that politics is about more than economics, and that the battleground now is about culture and identity rather than a few quid here or there. This misses the point. The great virtue of economic growth, as Ben Friedman showed, is that it creates a climate in which toleration and openness can thrive. Stagnation, by contrast, gives us closed minds, intolerance and fanaticism. If centrists are sincere in wanting a more civilized and tolerant politics, they must create the material conditions for these. In fact, in office they did the opposite.

It���s common to claim that Corbyn has enabled antisemitism. But it is centrists who enabled Corbynism by creating the conditions in which he ��� and indeed the far right ��� can thrive. A serious politics requires an awareness that political behaviour has a structural basis and offers a way of creating the structures that generate the ideals they favour. Centrists, however, do none of this. All they have is a sense of their own entitlement to rule and a smug moral superiority.

Rather than wag the finger at those of us who feel compelled to make the tragic choice between two deeply flawed potential Prime Ministers, centrists should show more humility and more cognizance that it is their acquiescence in inequality and austerity that got us into this mess.

* I know we do: I voted Green in the euro elections, but Jonathan Bartley and Sian Berry aren't going to be Prime Minister.

July 19, 2019

Labour's antisemitism problem

Simon Wren-Lewis says that, faced with the prospect of a Johnson-led government, Jeremy Corbyn is the lesser of two evils and should therefore be supported. I tend to agree, but with two caveats.

One is that we cannot dismiss Labour���s problem with antisemitism. True, nothing Corbyn has ever said is as overtly obnoxious as Johnson���s talk of ���picaninnies��� or that Irishmen are all called Murphy. The evidence for his antisemitism consists in a deafness to anti-semitic tropes; a failure to call it out when he should; and a closeness to the sort of moralizing conspiracy theory that can spill over into antisemitism.

Mild as they are compared to Johnson���s racism, however, these are genuine failures. For obvious reasons, Jews are rightly awake to tail risk ��� the tiny chance of genuine hostility. If even one Jew is made to feel sincerely uncomfortable by the possibility that a Labour government even might be antisemitic, that is abominable. And it is an indictment of Corbyn.

My second caveat is that I don���t think Simon, or many leftists, are drawing the right inference from a wholly correct observation ��� that the media is horribly biased.

True, Labour���s antisemitism is being overplayed and Tory Islamophobia understated. True, some of those accusing Labour of antisemitism are gross hypocrites who were happy to acquiesce in subtle antisemitic slurs on Ed Miliband. True, there is no equivalence between the gibberings of a few twats in Labour and the overt and systematic racism of the Tories��� ���hostile environment��� policy.

True, true, true,

And irrelevant. Labour faces the same problem as football team when the referee is bent. Its mild infractions are penalized whilst its opponents can get away with serious fouls.

But what should a team do in such circumstances? Complaining would energize its supporters. But the ref will deny his bias and book players for dissent. Complaints won���t win the game.

Instead, what the team must do is to be cleaner than clean. Its only hope is to not make any risky tackles which give the ref an excuse to award penalties. As my old dad said, ���never give a cunt a chance to be a cunt.���

And this is what Labour has failed to do. In failing to ruthlessly expel anyone even whiffing of the possibility of antisemitism, it has given its enemies something to exploit: the need for Labour to win an election trumps anybody���s right to be a member of it. This might be a moral failure, but it is certainly a horrible tactical blunder.

All of which raises the question. Is Simon right to say the only choice is between Johnson and Corbyn? But could we do better? Could we have a radical Labour party without Corbyn and his public school Stalinist entourage?

Many decent leftists are cleaving to Corbyn in the fear that throwing out the fetid bathwater of antisemitism would also mean abandoning the (so far half-formed but nevertheless inspiring) prospect of a genuine alternative to actually-existing capitalism and retreating back to managerialist defences of inequality. I honestly don���t know how justified this fear is, although it is troubling that too few of Corbyn���s critics are striving to allay it. And whilst this fear exists, Simon is right: Corbyn is the lesser of two evils.

July 17, 2019

Costs of recession

The Resolution Foundation���s James Smith has written a nice paper on the likelihood of recession and the fact that, with monetary less able to support the economy, we need to think about alternative ways of tackling recessions. I just want to amplify what he says in two ways.

First, there���s increasing evidence that recessions can do long-term damage, even if the economy appears to bounce back in the short-term. There are at least three mechanisms here:

- Education. Bryan Stuart shows that the 1980-82 recession in the US ���generated sizable long-run reductions in education and income.��� Parents who suffer a drop in income spend less on children���s books and educational trips, and this makes them less likely to go to college a few years later. Such effects are magnified if bad macro policy causes restraints upon public spending on schools and libraries.

- Productivity. Recessions increase uncertainty, which depresses investment in both capital and R&D, leading to lower productivity growth. The Bank of England���s Dario Bonciani and Joonseok Jason Oh say:

Shocks increasing macroeconomic uncertainty can lead to very persistent negative effects on economic activity that last well beyond the business cycle frequency.

- Scarring. A recent paper by Erin McGuire shows that people who grow up in hard times ���invest less in risky assets throughout their lives, invest more in property, and are less likely to be self-employed.��� This corroborates research (pdf) by Ulrike Malmendier and Stefan Nagel. Through this channel, recessions can reduce entrepreneurship and increase the cost of capital even decades later.

Against all this, it is theoretically possible that recessions have a beneficial ���cleansing��� (pdf) effect: in driving inefficient firms out of business, they make it easier for more efficient ones to expand, and this raises productivity growth.

One Big Fact tells us that effect hasn���t operated recently: productivity has flatlined since 2008. One reason for this is that financial crises can hamper the expansion of even the best firms, in part by causing them to fear for the future availability of credit.

All this evidence makes me believe that recessions are more costly than I (and I suspect others) previously thought. Policy-makers should, therefore, do more to prevent or mitigate them.

Which brings me to my second amplification of James��� paper. ���We can���t recession-proof the economy��� he says. He���s right. We cannot prevent recessions by seeing them in advance and relaxing monetary or fiscal policy, simply because recessions are unpredictable. Back in 2000 Prakash Loungani wrote that ���the record of failure to predict recessions is virtually unblemished���, a fact that remains true today. The Bank of England did not cut Bank rate to 0.5 per cent until March 2009, a full year after the recession began.

For me, this requires alternative policies. Some should aim at reducing the risk of recession, for example by ensuring that banks are so well capitalized that losses needn���t lead to cuts in lending. Others should aim at moderating recessions via strong automatic stabilizers, such as progressive taxation and a strong welfare state ��� and perhaps a job guarantee.

Yes, such changes might reduce the benefits of the cleansing effects of recession. I suspect, though, that such productivity-enhancing gains could be achieved at much lesser cost by policies to increase product market competition.

Of course, recessions are an inevitable aspect of capitalism. With their costs now greater than previously thought, it is all the more important to mitigate them, which requires not just macro policy but also institutional change.

July 11, 2019

Don't abolish private schools

Should we abolish private schools, as some Labour activists are advocating? For me, this is a tricky issue.

The case for not doing so is simple ��� freedom. My instinct is that folk should be free to spend their money how they want. (I know nobody values freedom these days but I���m an old man, so indulge me.)

As with many other activities, however, this freedom imposes negative externalities onto others.

One is that it creates unequal opportunities. Fees at Oakham School ��� to take my neighbour ��� are more than three times as great as average spending (pdf) per pupil in the state sector. Such massive inequality in spending is bound to cause some inequality in results. It���s no surprise, therefore, that the privately-schooled are over-represented at Oxbridge and in top jobs.

The second is that the excessive influence of people from private schools in politics and the media causes systematic distortions. Our elite is arrogant, overconfident, out of touch and too heavily influenced by an Oxford Union conception of politics as a game of facile debates rather than of technocratic expertise.

But, but, but. There���s a question here. Do private schools instil overconfidence or do they merely reveal it? Would Cameron, Rees-Mogg, Farage and Johnson still be arrogant pricks if they had gone to a decent state school instead? Certainly, they would still have several advantages, such as a wealthy upbringing and family contacts.

It���s hard to say. Most parents who can afford to do so send their kids to private schools, and the ones who don���t are sufficiently different from the others that they hand down very different cultural capital to their offspring.

In fact, abolishing private schools might merely replace one set of arrogant dickheads with another. I say so because of something said by in 1957 by Michael Young (whose son is of course an advert for abolishing private schools):

If the rich and powerful were encouraged by the general culture to believe that they fully deserved all they had, how arrogant they could become and, if they were convinced it was all for the common good, how ruthless in pursuing their own advantage (The Rise of the Meritocracy).

Fred Goodwin, boss of RBS during its downfall, for example, went to state school. If private schools gave us Brexit, state schools gave us the financial crisis.

So, what are the alternatives to abolishing them?

One possibility is to impose quotas on how many people universities and professions can draw from private schools ��� a more rigorous and widespread version of the Texas law which requires that universities offer places to the top 10% of pupils from any school (a measure passed into law by that notorious communist George W. Bush). The virtue of this is not so much to promote social mobility, which is a dubious aim. It is instead to ensure that elites are more cognitively diverse. If fewer BBC journalists were privately educated, we might see less deference to ���Boris��� and the promotion of a different conception of politics.

Secondly, we should have more progressive income tax. This would, in effect, be a way of pooling the risks of having gone to a good or bad school. And in reducing top incomes it would depress demand for private schooling.

Thirdly, we need more egalitarian forms of decision-making in companies and in politics. Properly structured systems ��� those that reduce the risk of groupthink ��� might reduce the danger from overconfident leaders, be they privately or state educated*.

Such systems might achieve the twin benefits of preserving freedom whilst reducing the externalities of private education.

But only might. ���Meritocrats��� might resist progressive taxes and collective decision-making, believing them to be restrictions to their entitlements. And perhaps there really is causality from private schooling to overconfidence ��� if all that talk of instilling ���leadership��� isn���t just bull. My preference, though, is to try these methods first, If we don���t there���s a danger that abolishing private schooling would be like abolishing the monarchy; it attacks epiphenomena of privilege rather than their true causes and effects.

* Overconfidence can be a good thing, but more often in entrepreneurs than in established organizations. One case for quotas is to force the privately educated into professions where overconfidence is a virtue rather than vice.

July 10, 2019

Disaster capitalism: some doubts

Could ���disaster capitalism��� actually work? This is the question posed by Grace Blakeley, who writes:

A no-deal Brexit is to Johnson and Hunt what the financial crisis was to Cameron and Osborne ��� an opportunity to rebalance power and wealth in society away from labour and towards capital.

Here, some distinctions are necessary.

One is between effects and intentions. A precedent for successful disaster capitalism was the 1981 recession. It greatly weakened workers��� bargaining power and caused capital scrapping, both of which helped to restore profitability. This, however, was not Thatcher���s stated intention: she did not expect her policies to cause a recession. And it might not have been her actual intention either.

Similarly, I don���t know whether Johnson really believes a no-deal Brexit will help increase capitalists��� wealth and power: I can���t read minds and in his case I don���t want to. But it doesn���t matter. No-deal might or might not have this effect, whether Johnson intends it or not.

A second distinction is between free market policies and pro-capitalist ones.

Grace claims that ���Cameron and Osborne used the financial crisis as an opportunity to shrink the state.��� I���m not sure about this. As Sam says, they ���totally failed to make a broad-brush case for free markets��� and failed to sufficiently improve public sector efficiency with the result that their cuts were unsustainable. As a result, the share of public spending in GDP this year, at 37.9%, is greater than it was in the early 60s or in the early years of New Labour.

But no matter. Healthy capitalism requires a biggish state not only to provide subsidies to banks, corporate welfare, infrastructure and automatic stabilizers, but also to provide good enough public services to diminish discontent. Shrinking the state and supporting capitalism are two different things.

A third distinction is between capitalism���s material conditions and its ideological climate. For reasons I���ll come to, I���m not sure that no-deal Brexit would materially benefit capitalists. But it might create an ideological climate favourable for some. We know that tougher economic times breed pessimism, illiberalism and intolerance. This would be especially the case if the EU, Ireland and the ���Remainer establishment��� get the blame for the ill-effects of no-deal. This would hurt the left, not least by shifting the agenda towards reactionary nationalism. That would help some sections of capital.

A fourth distinction is between the interests of financial capital and industrial capital. There are ways in which a no-deal Brexit might help financial capitalists. But aside from Johnson���s promised cut in incomes tax, I���m not sure they are terribly powerful, for example:

- A fall in sterling would give windfall profits to holders of overseas assets. There���s nothing especially Machiavellian about this, though. Anybody with a moderately well-managed Sipp can take some advantage of this.

- A recession would devalue some companies sufficiently to make them cheap for vulture capitalists who have either the leverage or liquidity to snap them up. Doing so, however, is a very risky strategy with huge downsides as well as upsides. As John Campbell has pointed out, distress risk doesn���t pay off on average. Those who bought Carillion or Debenhams when they looked cheap would confirm this.

- The policy response to a no-deal recession would involve cuts in interest rates and QE which would promote financialization and boost asset prices. Now we are near the zero bound, however, the scope for rate cuts is limited. And Johnson���s promises suggest that an (albeit half-arsed) fiscal easing might limit the extent of QE*.

Nor am I convinced that disaster capitalism would improve the prospects of industrial capital.

It could do so in theory in the way it did in 1981 ��� by causing widespread capital scrapping which would raise returns on capital partly by reducing competition and partly simply by cutting the denominator.

A striking feature of recent years, however, has been that this mechanism has not operated. Even at the height of the crisis there were fewer corporate liquidations than there were (pdf) in the 80s and early 90s. Low interest rates and banks��� forbearance have limited capital scrapping. It���s not obvious why this should dramatically change in the next recession.

What���s more, the restoration of real profitability requires more than capital scrapping. It also requires an expansion of profit opportunities. No-deal, however, would have the opposite effect. Increased (pdf) trade barriers and greater policy uncertainty would actually restrict such opportunities and deter investment.

I don���t, therefore, see how a no-deal Brexit would reinvigorate capitalism. To claim that it is part of a cunning plan by Johnson is to give the man too much credit. Sometimes, people are as stupid as they look.

* Given the inflation target, more fiscal easing means less monetary easing.

July 5, 2019

Simplicity: smart & stupid

David Gauke has been rightly praised for this:

Rather than recognising the challenges of a fast-changing society require sometimes complex responses, that we live in a world of trade-offs, that easy answers are usually false answers, we have seen the rise of the simplifiers.

This echoes a fine piece by Ian Leslie who says:

The disease of politics today is not populism, so much, as simplism: the oversimplification of complex problems.

I want to quibble, though. There are ��� to simplify! ��� two different types of simplicity, the stupid and the smart.

Stupid simplicity is the sort that Gauke and Leslie are rightly decrying ��� the sort that denies the reality of complexity. This is the sort of simplicity that thinks there is a simple cause of our problems ��� be it immigrants, Joos or greedy bankers ��� or that there is a simple answer such as Brexit or higher taxes. Conspiracy theorists are often guilty of this simplicity. So too are those who fail to see trade-offs, such as between democracy and prosperity: both sides of the Brexit debate are guilty of this.

There is, however, a smart form of simplicity. It acknowledges that the world is complex and our cognition bounded, and so it looks for simple but empirically-based cognitive short cuts. Gerd Gigerenzer, for example, has shown (pdf) that simple rules of thumb can work well. And Robyn Dawes (pdf) and Paul Meehl (pdf) have both shown that simple statistical models often do better than professional judgments which try to explicitly acknowledge complexity. Sometimes, hedgehogs are better than foxes.

We see this in finance. If you want to know the chances of recession, it���s better to look at a simple indicator such as the yield curve than (pdf) at economists��� forecasts, which almost always fail to see recessions coming. And simple indicators such as the dividend yield, a moving average, foreign buying of US equities or the ratio (pdf) of consumer spending to wealth do a better job or predicting stock market returns than do the professionals.

Sometimes, even, simple policies do better than tricksy ones. Simply buying an index-tracker fund (pdf) means you will often do better than most fund managers who try to incorporate complexity into their stock-picking.

Which poses the question: can the same be said in politics? For me, one of the great virtues of a (high) universal basic income is that it recognizes that people often switch between unemployment, insufficient hours and low-wage work, and that there are huge deadweight costs in trying to assess needs. It���s a simple solution to complexity. In the same vein, simple institutions such as Robert Shiller���s macro markets might do a better job of insuring us against recessions than the impossibly complex job of forecasting them in advance. And part of the case for worker democracy is that dispersed wisdom can cope with complexity better than can top-down management.

My point here is that there are no general rules. Sometimes simple answers work moderately well: in a complex world, the best we can do is satisfice. But sometimes they don���t. All that matters is the evidence. It���s not good enough to pretend that there are simple answers, but equally, telling us that ���it���s more complex than that��� can be a false sophistication.

July 4, 2019

How not to be an arrogant prat

Dan Davies has said that financial regulators should have been active spread-betttors, because only this gives them hard knowledge of how nasty margin calls can be. The same should apply to everybody who expresses a political opinion.

The thing you learn from financial markets is that even your best ideas, your most diligently-research trades, often go wrong ��� and expensively so. Equity fund managers typically have only a few good stock ideas and most of what they do is either risk management or value-subtraction. And private equity managers expect many of their holdings to lose.

What you learn from spread-betting or (in my case) having to stand on a trading floor after one of your calls has gone wrong is that the only thing that matters is the facts. However much smoke your friends and colleagues blow up your jacksy, if prices rise after you���ve shorted or fall after you���ve bought, you���ve lost. All that counts is the book.

In punditry, it is otherwise. As Dan says, ���being really aggressively unpleasantly wrong on your supposed subject of expertise has no downsides in the UK media.��� Christopher Booker kept his job at the Sunday Telegraph despite his climate change denial. Those who told us that leaving the EU would be easy continue to expound despite their ideas being marked to market and found in the red. And those who greeted Theresa May as a new Thatcher continue to opine, heedless of their earlier error.

Granted, regular confrontation with expensive losses can turn traders into thick-skinned bumptious arrogant prats, who remember their successes but forget their failures ��� the sort who confuse the size of their pay-packet (often earned through mere asset-gathering or by state bail-outs) with the size of their talent.

But there is another reaction. This particular school of hard knocks can teach you humility ��� to be aware that the world is a more complex thing than your limited cognition can comprehend. The best traders and investors draw (at least) four inferences from this. Political pundits should too. These are:

- Always ask of any item of news: is it noise (pdf) or signal (especially if it corroborates your prior belief)? One of the great errors traders make is to trade (pdf) on noise ��� something that looks like genuine information but in fact tells us nothing about the future or is even downright misleading. Theresa May called a general election in 2017, believing that council election results and opinion polls were a signal about her electoral prospects. In fact, they were noise. Everybody commenting on a poll now should therefore consider whether these have any more predictive power than they did then, or whether they are just noise.

- Remember there���s a margin for error. If you are using a formal model, tell us what its confidence interval is and why past relationships break down. Do the same even if you are using an informal one: confidence intervals and parameter instability exist whether you know them or not.

- Know the edge of your competency. As Charlie Munger says, you must know what you don���t know. There are no general purpose experts. Be honest about the gaps in your knowledge.

- Value cognitive diversity. The best investors welcome people who disagree with them, because these help them test their own ideas better. Whilst echo chambers might in some cases yield useful information they are more likely to produce groupthink and overconfidence. Just because a nice guy agrees with you does not mean you are right.

Although following these rules might well help you think better (I say this without of course always following them myself) I���m not sure they provide a viable business model. In the media ��� and certainly in politics - there is demand for overconfident prats. But then, there are trade-offs everywhere. One of these might be that there���s sometimes a tension between an ability to think properly and an ability to earn a living.

July 3, 2019

Class and optimism

One thing that attracts people to Boris Johnson is his cheerfulness about Britain���s prospects. Liam Halligan and Owen Patterson both praise his ���sunny optimism���, whilst Matthew Leeming writes ��� I kid ye not ��� that ���we need a cheerleader to remind us we are an erect and manly people.��� But I wonder: is there a class aspect here?

I ask because of recent paper by Erin McGuire. She shows that:

Individuals who begin their lives by observing an economic downturn remain pessimistic and risk averse with respect to investments over the course of their lifetimes.

This corroborates work (pdf) by Ulrike Malmendier and Stefan Nagel and by (pdf) Miguel Ampudia and Michael Ehrmann. And it���s consistent with research by Henrik Cronqvist and colleagues. They show that people who grew up in poorer homes or who entered the labour market in recession tend to avoid growth stocks even years later.

Much the same might also be true for attitudes to unemployment. Memories of the Great Depression suppressed wage militancy in the 1950s, just as memories of the financial crisis might have caused millennials to be timid today. Wolfgang Maennig and Markus Wilhelm have shown that spells of unemployment depress well-being even after people return to work, perhaps by inducing the fear that it could happen again.

All this suggests that hard times in our formative years make us pessimistic long after those times have passed.

Which is where class comes in. Being posh insulates you somewhat from hard times, thus making you more optimistic than the rest of us. Johnson and I are both of an age to have spent our formative years during a time of soaring unemployment. But whereas I saw it close up, Mr J did so from a safer distance. It is perhaps therefore no accident that he has a ���sunny optimism��� and I, well, don���t.

The mechanism here was described by David Hume. Our lived experience creates impressions which enter our minds ���with most force and violence���, whereas reports are only ���faint impressions��� of these. Those who have experienced poverty or unemployment, or seen them close up, have therefore a greater fear of it than those who only saw them from a distance, if that.

What I���m describing here is a little different from the tendency for posh people to be more confident than the rest of us, but perhaps connected. My point is that posh folk are more optimistic than others not just about their personal prospects, but about prospects for the economy generally. Of course, you can think of counter-examples to this ��� of posh but melancholic people (Townes van Zandt?) ��� but I suspect there is a tendency here. This fits with the fact that leading Brexiters such as Rees-Mogg and Farage as well as Johnson come disproportionately from comfortable backgrounds.

Of course, optimism is sometimes justified. But this isn���t my point. My point is merely that our attitudes and preferences are not ���given��� as simplistic neoclassical economics often pretends. They are instead endogenous (pdf), shaped by among other things culture, gender, history, peer pressure and ��� yes ��� class.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers