Chris Dillow's Blog, page 33

February 26, 2019

Brexit as symptom

Simon says that Brexit is a ���symptom of a deeper malaise��� ��� of a dysfunctional political-media system that gave us economically illiterate austerity.

I agree that austerity caused Brexit, not least because as Ben Friedman has shown, stagnant incomes make people more hostile to immigrants. But I wonder: is there an even deeper malaise here ��� namely, a fundamental failure of capitalism?

What I mean is that capitalism was faltering even before the banking crisis. For example:

- The real income of the median UK household, after housing costs, rose only 1.6% per year in the five years to 2007, well down from the 2.4% growth of the previous thirty. This wasn���t merely because growth was captured by the rich: GDP per head in that period grew only 2.1% per year, which was weak by the standards of previous expansions.

- Business investment accounted for less than 10% of UK GDP in the mid-00s, compared to over 12% in the late 90s. This reflected what Ben Bernanke in 2005 called a ���dearth of investment opportunities��� in western economies.

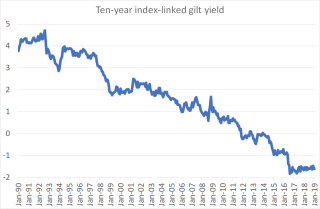

- Real bond yields were trending downwards from the early 90s. Whether this reflected a savings glut, investment dearth or shortage of safe assets is in a sense beside the point. The downtrend betokened a loss of economic dynamism: a lack of belief in growth caused investors to prefer safer assets.

These signs of stagnation might have a common cause ��� that, as Andrew Kliman (big pdf) and Michael Roberts have shown, rates of profit in many developed economies had been falling since the 60s. That sapped capitalists��� motive to invest in productive assets, thus depressing growth.

All this is consistent with Ravi Jagannathan���s claim (pdf) that the 2008 crisis was ���the symptom not the disease.��� It was a bust without a preceding boom.

To see the point, imagine that (contrary to reality) there had been an abundance of highly profitable business investment projects in western economies in the 00s. The ���glut��� of savings from Asian economies would then have financed these rather than house price inflation. We���d have seen genuine real growth rather than bubbles and malinvestments. We���d not then have had the crisis.

And as Nick Crafts says, without the crisis we���d not have had austerity and hence Brexit. This isn���t because the crisis necessitated austerity. It���s because the recession weakened support for the Labour government and the post-crisis rise in government debt allowed the Tories and the media to exploit illiterate debt phobia.

There is, I think, a pretty clear line from capitalist stagnation to the 2008 crisis, to austerity and hence to Brexit.

My dispute with Simon echoes an old one between Marxists and social democrats. Whereas the latter tend to emphasize the role of bad policy, we Marxists stress deeper-rooted failings of capitalism.

The disagreement here is, I suspect, one of emphasis. Where Simon and I agree is that Brexit is indeed a symptom. In this sense, there���s a sharp difference between us and Tory Remainers such as Anna Soubry who supported austerity and Lib Dems and other centrist Remainers who acquiesced in it. They seem to think Brexit happened because voters suffered a fit of irrationality to which they were immune. This is silly narcissism ��� a morbid symptom of what we get when one���s political opinions are not anchored in social science.

February 23, 2019

Missing the elephant in the room

Giles Fraser���s now-notorious piece has copped a ton of stick. This is justified, but nobody has articulated my own discontent with it.

Fraser does raise some important questions. His assertion that care work should be done within the family (I���ll gloss over his sexism) echoes a point made by Michael Sandel and before him Michael Walzer, that some activities should not be monetized, that to do so drains them of their essential meaning, of love and intimacy.

In itself, this is a reasonable claim. But Fraser misses two things. One is that there���s another value here ��� efficiency. The division of labour can benefit everyone: employing carers can free up children to do other things, and allow older people with special needs to get specialist help. The other thing Fraser misses is the empirical evidence. Do paid carers really diminish love, intimacy and community? Or might it be that they do the opposite: they widen the social circle of the older person, and might improve family relationships by taking stressful interactions out of them.

Fraser���s claim that social mobility and freedom of movement ���could not have been better designed to spread misery and unhappiness��� also speaks to an important possible trade-off ��� that perhaps freedom does reduce happiness: for example, American women���s happiness seems to have fallen since the 70s whilst their career options have increased.

What Fraser is alluding to here is getting at here is Pitirim Sorokin���s dissociative hypothesis ��� the idea that people who are upwardly socially mobile suffer a sense of isolation from being uprooted. And again, he ignores the empirical evidence. Tak Wing Chan, for example, has found the opposite:

On a range of social relational indicators as well as on several direct measures of well���being, the upwardly mobile tend to do as well as, and in many cases better than, those who are immobile in the working class.

Personally, I was surprised by this: my experience was consistent with Sorokin���s theory. And we might quibble with this finding. It���s based upon a curious definition of class mobility ��� as movement from the working class to salariat ��� and so might not capture the dislocation that the extremely upwardly mobile suffer. The IFS, for example, has shown that men from poor families are more likely to be single in later life even if their incomes rise. And we might ask whether what���s true of past generations is true now: the fact that young graduates almost universally want radical social change might speak to disappointment at what mobility has given them.

Again, though, Fraser doesn���t address this evidence. Faced with tricky trade-offs between values, all he does is assert a preference. It���s as if he wants to vindicate Alasdair MacIntyre���s claim that we have lost the ability to talk coherently about morality.

But there���s something else Fraser misses - capitalism.

There���s a big difference between care work being done by dedicated professionals with big support networks and it being done by over-stressed minimum wage workers rushing from client to client. Neoliberal capitalism (and Tory/centrist austerity) gives us the latter, not the former.

And the mobility which Fraser berates isn���t wholly a matter of people choosing to become ���rootless Ronin���. It���s also a response to the failure of capitalism to provide decent jobs near to where people live.

Brexit, of course ��� and especially the no-deal Brexit Fraser wants ��� will of course exacerbate both these problems. A weaker economy means worse job opportunities and less chance of higher public spending on social care.

In this respect, Fraser has given us an example of what most non-leftist political discourse is about. It���s a form of displacement activity, an attempt to blame anything for our current predicament except the failures of capitalism.

February 21, 2019

Structure vs agency in economics

Will Davies made a typically good point yesterday when he tweeted that the ���impoverishment of the ���sociological imagination��� over decades��� has left people ���people unable to speak critically of systemic problems, without personifying them���.

What we have today is a crude moralistic tribalism in which people divide simply into goodies and baddies. We see this in the ���two minutes hate��� against Shamima Begum ��� which is oblivious to the fact that one���s rights do not depend solely upon one���s moral character. We saw it in the silly debate about whether Churchill was a hero or villain, much of which effaced the fact that he was a complex character who happened to be exactly the type we needed in 1940. And we see it when lefties blame low pay upon greedy bosses and the financial crisis upon greedy bankers. I agree with Will that this mentality is also behind the rise of antisemitism on the left; antisemitism is the socialism of moralizing fools.

What such crude discourse misses is an aspect of the sociological imagination ��� the ability to see that society is shaped by structural forces which can cause outcomes to differ from the intentions and moral character of agents. It was this imagination ��� in fact, important insight ��� that Adam Smith was using when he wrote that ���"it is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest."

The converse can also be true. Marx thought that exploitation and low wages arise not from the greed of capitalists but from the forces of competition*:

Capital is reckless of the health or length of life of the labourer, unless under compulsion from society���But looking at things as a whole, all this does not, indeed, depend on the good or ill will of the individual capitalist. Free competition brings out the inherent laws of capitalist production, in the shape of external coercive laws having power over every individual capitalist.

Chuck Prince, then boss of Citi, made a similar point in 2007 when he said:

When the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will be complicated. But as long as the music is playing, you���ve got to get up and dance.

What he was driving at was that excessive risk-taking wasn���t caused so much by ���greed��� as by men responding to incentives: each individual bank had an incentive to gear up for fear of falling behind others.

Prince, Smith and Marx all agreed upon the key point for my purposes ��� which is that structure trumps agency, that social outcomes cannot be reduced to individual morality or character.

But is this true?

A good reason to suspect not is the existence of monopoly and monopsony. These relax competitive pressures and so give bosses room for agency, to offer better wages. Jeff Bezos would not become a pauper if Amazon gave its workers better pay and conditions.

Even here, though, structure isn���t wholly absent. When Amazon was a smaller company, higher costs and prices might well have attracted competition and thus hurt the company. Many ideas outlive their empirical base: it could be that Bezos���s desire to screw down wages is one of these.

Also, of course, firms��� ability to hold down wages and conditions is facilitated by weak aggregate demand. Is this a failure of agency ��� simple bad policy-making? Or is it instead structural ��� a result of capitalists��� political pressures upon governments?

What���s more interesting to me, though, are hybrid theories ��� ones which combine structure and agency. I���m thinking of two classes here, though there are no doubt more.

One is the role of social norms. These have structural origins but shape morality. We can think of the rise of neoliberalism as being in part a sign of an erosion of norms against rapacity, short-termism and rent-seeking: this is Jesse Norman���s theory in Adam Smith: what he thought and why it matters.

A second category are selection mechanisms. It���s very possible that bad character ��� psychopathy or narcissism ��� is selected for in at least some businesses, and that incompetent overconfident fanaticism is selected for in politics.

There is, I think, a good debate to be had upon these issues. What is unacceptable to me, however, is a simple-minded attempt to blame social problems upon bad people. Such silly moralizing is a barrier both to understanding and changing the world.

February 19, 2019

The irrelevant Independent Group

The Independent Group claims to value an ���open, tolerant and respectful democratic society��� and to oppose Brexit. It wills the ends, but not the means. It fails to see that Brexit and intolerance are the product of economic conditions, and is silent on what to do about those conditions. It looks therefore like a bunch of narcissists complaining that people are not like them whilst offering no real solutions.

As I���ve said many times, the key to understanding politics today is Ben Friedman���s book, The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth, published in 2005. He shows that economic growth begets liberal attitudes and that stagnation breeds intolerance. Subsequent events vindicate him perfectly. As Thiemo Fetzer has shown, pro-Brexit attitudes are ���strongly and causally associated with an individual���s or an area���s exposure to austerity.��� In a separate vein, Nick Crafts has blamed Brexit upon the banking crisis.

In this sense, economic stagnation is the cause of Brexit and of the turn away from the liberal values the IG claims to espouse. And this stagnation is still with us. Only today the ONS reported that productivity fell last year: this means it has risen only 0.2% a year since 2007 compared to 2.3% per year in the thirty years before then. Because of this, real wages are still below their pre-crisis peak.

The IG, however, is silent about this. Its statement (pdf) makes no mention of austerity or stagnation. In fact, pretty much its only substantive reference to the economy is to government���s ���responsibility to ensure the sound stewardship of taxpayer���s money���, which doesn���t inspire hope of a firm rejection of austerity.

It claims that our politics is ���broken���, but is blind to the fact that capitalism is broken too, and that this is a major cause ��� perhaps the major cause ��� of our broken politics. Phil says the IG has ���learned nothing, nothing since 2015.��� I���d question only the year here: it seems it has learned nothing since 2008.

Now, you might reply that it���s unreasonable to expect a new political grouping to have detailed policies. True enough. The problem with the IG, though, isn���t that it doesn���t have solutions: it���s that it doesn���t even see a problem. There���s a good debate to be had about how far capitalist stagnation can be fixed by fiscal and monetary policy alone, and how far it needs institutional change too. The IG shows no sign of entering this debate, though.

At least one of its members has form here. Last year Chris Leslie wrote a paper, Centre Ground (pdf), which also largely ignored the financial crisis. I criticized him then for failing to see that the crisis necessitated a rethinking of the relationship between the state and the private sector. He shows no sign of learning this lesson: his claim to believe in ���evidence-based��� policy-making is a sign of astounding lack of self-awareness.

Herein, for me, lies the great virtue of Corbyn (perhaps his only virtue). He at least sees the problem, that the economy is broken and that the Left needs new policies for new times ��� just as Blair saw this a generation ago. The IG, by contrast, is stuck in a 1990s timewarp, unaware that the world has changed.

Granted, Corbyn might be right in the same way that a stopped clock is sometimes right. For me, this is unimportant. What matters is that we have something like the right policy ideas for our changed economic times. I can���t say how much the IG will affect politics. But I do know that whilst they have no awareness of our economic problem, they will be an intellectual irrelevance.

February 15, 2019

Non-expiring information

I liked this line from this piece at Farnam Street:

A lot of us are on the treadmill of consuming expiring information.

Expiring information is not the same as trivia, which can be useful and interesting. It is instead knowledge which has a short shelf-life.

A lot of talk about Brexit has been expiring information. We are no nearer today to knowing what type of Brexit we���ll get (or even if or when we���ll get it) than we were on June 24th 2016. All the effort expended over the last 32 months on wondering what will happen has therefore been largely wasted. News which looked useful at the time turned out not to be. It was more noise than signal.

Much the same is true in stock markets. It���s very easy to spend your life accumulating lots of detailed factoids about individual companies which give the impression that you are an expert but which are otherwise useless. Either they have no ability (pdf) to predict future returns, or if they had it once they might not have it now or in future. Such factoids are expiring information: in fact, insofar as the efficient market hypothesis is correct, the expiry date has passed.

What can we do about this? I have two responses.

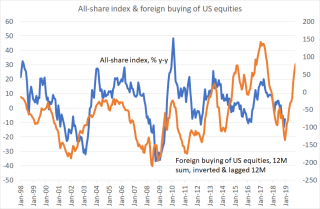

First, I ask of any claim or fact: so what? Why should I care? In stock markets, we have a handful of factors which have (at least in the past) been good lead indicators of returns on the aggregate market. These include: the dividend yield; foreign buying of US equities (a great indicator of investor sentiment) and ��� yes ��� the time of year. The rest is noise.

Similarly, if I want to know whether the US will experience a recession soon, I look at the yield curve and consumption-wealth ratios (pdf) and discount heavily most other information.

This point probably generalizes to fields other than finance.

Warren Buffet, I suspect, does much the same thing. Despite Farnam Street���s portrayal of him as a gatherer of useful facts, his success has rested largely upon exploiting two big things: an ability to raise very cheap finance; and the buying of defensive stocks, a category of share we���ve known since 1972 to be under-priced.

Secondly, I try to collect examples and counter-examples of general purpose knowledge. For me, there are two big sets here.

One set is of cognitive biases ��� mistakes we make and which we should avoid in future decisions.

The other set is of mechanisms. As Jon Elster said, the social sciences are essentially a collection of mechanisms. Sometimes, for example, there are mechanisms through which markets work well to allocate resources and sometimes there are ones (pdf) through which they work badly.

What I���m doing here is blurring the distinction Ernest Rutherford (probably) made when he said that all sciences were either physics or stamp-collecting. It���s true that the social sciences don���t have the handful of powerful predictive laws that physics does. But this doesn���t mean we must content ourselves merely with gathering disparate unrelated facts. Facts can be organized into examples and counter-examples of mechanisms ��� although we might never have a complete inventory of these.

I���m also doubting the relevance of the ancient distinction between foxes (which know many things) and hedgehogs (which know one big thing). The important thing isn���t whether you know one thing or many things, but whether you what what���s relevant and what���s not.

February 13, 2019

The pawn mistake

The ridiculous Digby Jones has tweeted:

Hey Mr Tusk. Those who pushed for Brexit did have a plan but it required your lot not to bully the UK, for Remoaners & the Establishment not to sabotage the wish of the majority & for Jezza���s mob not to play tribal party politics with a major National issue.

Many have pointed out that this is imbecilic: a plan that only works if people behave exactly as you���d wish them to rather than how they are likely to is no plan at all: it is merely a voice in your head.

When somebody is saying something very stupid, however, it���s a fair bet that ideology is involved. The ideology here is not just the fanatical Brexitism that induced wishful thinking but perhaps something else. It���s an aspect of managerialism ��� a belief that other people are pawns to be moved at will rather than conscious agents with motivations of their own*.

The most egregious examples of the errors of seeing others as pawns come from the failure of top-down targets, as described by Jerry Muller in The Tyranny of Metrics. For example, academics' pressure to publish has contributed to mediocre research and the replication crisis. Schools��� targets have led to endless revision and a focus upon the marginal student to the neglect of both the strongest and weakest. Waiting-time targets distort clinical priorities. Immigration targets deter foreign students. Sales targets encourage workers to mis-sell financial products, cook the books and increase banks��� risk exposure. And so on. Such errors result from an unthinking assumption that people can be easily manipulated like pawns, rather than have their own motives and agency and ways of responding.

This error can also lead to motivation crowding out. If you try to manipulate people by giving them financial incentives, you might displace (pdf) other motivations such as professional pride or altruism.

Julian Le Grand has highlighted the dangers here:

The relationship between the assumptions and the realities of human motivation and agency���are crucial to the success or otherwise of public policy���Policies that, consciously or unconsciously, treat people as pawns may lead to demotivated workers. (Motivation, Agency and Public Policy, p2)

It would be wrong to attribute this error only to managerialists, however. Many of us are prone to what David Navon has called the egocentric framing error. I suspect it explains the well-known IPO effect, whereby newly-floated shares generally do badly in the months after issuance: it���s because investors under-appreciate the fact that owners choose to sell their business when it is mostly likely to be over-priced.

It is, however, what we are seeing with Brexit. Chris Grey has long complained that Brexiters pay insufficient attention to the motives and interests of EU negotiators. John Humphrys perhaps gave us the silliest example of this when he suggested that Ireland leave the EU.

What���s going on here is a form of narcissism or psychopathy ��� an inability to empathize with others and an urge to see them as mere pawns serving one���s own interests. This is why I say it���s an aspect of managerialism: narcissists and psychopaths are over-represented in boardrooms.

It is, however, nothing new. This has been the attitude of tyrants and despots down their centuries. As the young Marx said:

Despotism's only thought is disdain for mankind, dehumanized man; and it is a thought superior to many others in that it is also a fact. In the eyes of the despot, men are always debased. They drown before his eyes and on his behalf in the mire of common life

We should therefore, perversely, be grateful to Jones. He has reminded us of one of the overlooked costs of inequality ��� that it creates and sustains among the powerful a contempt for other people.

* Good management, of course, is wholly aware of the dangers of treating people as pawns. We must, however, distinguish been management and managerialism ��� the latter is an ideological distortion of the former.

February 12, 2019

The forecasting record

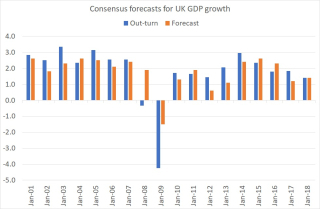

The ONS says GDP grew by 1.4% last year. 1.4% is a significant number: it is exactly what the private sector economists surveyed by the Treasury predicted in December 2017 that growth would be in 2018.

Granted, this bulls-eye might not survive future revisions to GDP estimates. But it reminds us that economists��� forecasts for growth are often not too bad.

My chart shows the point. It compares forecasts made in December for growth the following year to actual growth since 2001. Most of the time, the forecasts aren���t too far out. Where they go badly wrong is in recessions. Economists don���t see these coming. In December 2007 they forecast that GDP would grow 1.9 per cent in 2008. In fact it shrank. And even in December 2008 ��� after the banking crisis ��� they grossly under-predicted the depth of the recession.

This fitted the pattern. Back in 2000 Prakash Loungani wrote:

The record of failure to predict recessions is virtually unblemished. Only two of the 60 recessions that occurred around the world during the 1990s were predicted a year in advance. That may seem like a tough standard to impose on forecast accuracy. Maybe so���but two-thirds of those recessions remained un-detected seven months before they occurred.

In December 1990, for example, UK economists forecast growth of 0.3% in 1991. In fact, we got a 1% drop.

Economic forecasts, then, are reasonably OK except when we really need them.

Why? One possibility, suggested by Loungani, is that economists are slow to update their forecasts in light of news. One bit of evidence for this is that they also under-predicted the boom of 1988 (probably because they over-estimated the adverse effect of the 1987 stock market crash). Another possibility is that mainstream forecasters lack incentives to break with the consensus and predict recessions: it���s better to be wrong in a crowd. It���s for this reason that it is mavericks and those wanting to make a name for themselves who predict doom.

I suspect, though, that there���s something else. It���s that recessions are caused by things which are hard for macroeconomists to discern. For example, Xavier Gabaix shows how they can be caused by failures at large firms. And Daron Acemoglu and colleagues have described how they can be amplified by network (pdf) effects: trouble at a firm at the centre of a hub can spill over into other firms whereas trouble at a spoke does not. These are both part of the story of the 2008-09 crisis.

Macroeconomists are tolerably good at predicting fluctuations in aggregate demand. It is other things ��� such as supply shocks, network and peer effects or banking crises ��� they���re not so good at foreseeing.

It doesn���t automatically follow, however, that recessions are wholly unpredictable. US evidence strongly suggests that inverted yield curves lead (with a variable lag) to economic downturns. I suspect this is for the same reason that consumption-wealth ratios help predict bad times. It���s because such data aggregates the dispersed and fragmentary knowledge of countless individuals. There some specific conditions when the wisdom of crowds works better than experts.

February 10, 2019

In defence of conservative Marxism

James Bloodworth complains that the hard left is ���deeply conservative��� and opposed to regime change. I don���t want to address his specific argument ��� I���ve no aptitude for armchair foreign policy ��� but I do want to stand up for a conservative form of Marxism.

Opponents of Marxism tend to think of revolution as a sudden violent change ��� a replay of the storming of the Winter Palace. Most Marxists, and certainly not me, don���t think this way. Just as the transition from feudalism to capitalism was a lengthy process ��� and certainly not one caused by serfs protesting the unfairness of feudalism ��� so too will be the transition to capitalism. As Paul Mason has said:

Capitalism, it turns out, will not be abolished by forced-march techniques. It will be abolished by creating something more dynamic that exists, at first, almost unseen within the old system, but which will break through, reshaping the economy around new values and behaviours.

Some call this accelerationism, others call it interstitial transformation (pdf).

Transformation to what? Marx, famously, was vague. He rejected the idea that socialism could be designed as an abstract blueprint and then imposed upon society*. In 1843 he wrote:

We do not anticipate the world with our dogmas but instead attempt to discover the new world through the critique of the old���If we have no business with the construction of the future or with organizing it for all time, there can still be no doubt about the task confronting us at present: the ruthless criticism of the existing order, ruthless in that it will shrink neither from its own discoveries, nor from conflict with the powers that be.

Experience has taught us that Marx was right. A big reason for this lies in a key insight of conservatism ��� that our rationality and knowledge are bounded and that there are therefore tight limits to what top-down designers can achieve. This government is making a mess of Brexit and Universal Credit. And whilst a socialist government might contain more able people than Duncan Smith or Davis its task will be much greater. We need, therefore, something more than a centralized dogmatic construction of the future.

Instead, the shift to socialism will be much like the process of capitalist evolution ��� a process of trial and error. As Erik Olin Wright said:

What can be worked out are the core organizing principles of alternatives to existing institutions, the principles that would guide the pragmatic trial-and-error task of institution-building. Of course, there will be unintended consequences of various sorts, but these can be dealt with as they arrive "after the revolution." The crucial point is that unintended consequences need not pose a fatal threat to the emancipatory projects themselves.

Socialistic institutions and policies that work can be expanded, so that they eventually supplant capitalism. For example, tweaks to Universal Credit such as less conditionality and more generosity could transform it into a basic income; worker directors and a say on CEO pay might inspire workers to demand greater control at work; changes to procurement policy can be used to encourage coops; a national investment bank might lead to a greater socialization of investment; and so on. And various bottom-up non-capitalistic initiatives ��� be they farmers��� markets, community self-help initiatives, micro businesses or coops ��� would be encouraged by a leftist government. To take a couple of local examples (and all examples would be local), Vaughan College and plans to create a park along Oakham canal are socialistic projects.

It���s in this context that I���m sympathetic to demands for things such as full employment policies or high top taxes. I regard these as transitional demands ��� reasonable requests which might be incompatible with capitalism. And if or when the two are seem to come into conflict, we should ask how we might transform capitalism so as to remove its barriers to efficiency, justice and liberty.

So, for example, if (which isn���t very likely) high top tax rates cause a loss of government revenue, we might simply print money to cover the loss: one virtue of MMT is that it reminds us that we don���t need the tax revenue of the rich. And if such taxes cause bosses and financiers to quit, we can ask how to reorganize production to be less dependent upon rent-seekers.

Similarly, if full employment policies such as a job guarantee lead to a profit squeeze and falling investment, we might ask how to circumvent this by socializing investment or by using coops (pdf), perhaps in a Meade (pdf)-Weitzman (pdf), style to overcome the tendency for rising wages to squeeze profits and hence depress employment.

Now, I have of course been vague here. But that���s necessary. Socialism isn���t about imposing a design upon the economy. It���s about figuring out ��� in light of unforeseeable future conditions - what policies and institutions are best compatible with socialistic ideals. In this sense, Marxism is simply good orthodox policy-making ��� with the crucial difference that unlike orthodox policy-makers we do not assume unquestioningly that capitalism is inevitable or desirable. We Marxists are perhaps more conservative than Brexiters.

* The policies he proposed in the Communist Manifesto were social democratic ones, which were to a large extent enacted by 20th century governments.

February 8, 2019

Causes of stagnation

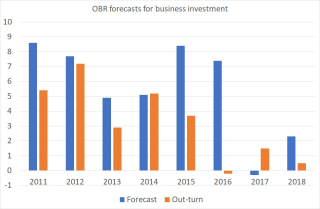

Ben Chu reports that business investment has been ���considerably weaker��� than the Bank of England had expected ���due to fears over a Brexit cliff-edge for trade.��� The Bank, however, has a history of over-predicting capital spending. In November 2014, for example, it predicted that business investment would rise 10% in 2015. In fact, it rose only 3.7%. And that was in the happy days before we knew about Brexit.

This is not an idiosyncratic failure by the Bank. My chart shows the OBR���s record at forecasting business investment, comparing forecasts made in November or December for growth the following year to the out-turn. In only two of the last eight years has investment exceeded expectations. In one of these years (2014) the excess was tiny, and in the other (2017) the OBR seems to have over-estimated the damage Brexit uncertainty would do.

Of course, over-optimism about 2016 can be attributed to firms delaying investment because of Brexit uncertainty. But the OBR was over-optimistic for most of the 2011-15 period too. That can���t be blamed on Brexit.

The OBR and the Bank have for a long time thought that high corporate cash balances, a small output gap and high profits would stimulate investment. This has proved too optimistic. Why? Here are six possibilities:

- A fear of technical change. If you invest in new robots, you risk being undercut in a few months��� time by a rival who has invested in cheaper or better ones. The prospect of rapid technical change can retard investment. This explains the paradox that there���s lots of talk about new technologies such as AI and robots but little investment in them.

- Intangibles. As Stian Westlake and Jonathan Haskel have shown in Capitalism without Capital companies��� assets ��� and especially the assets of growing companies ��� are increasingly intangible: things such as good ideas, brands or firm-specific technologies and skills. These are lousy collateral. Which means it���s hard to finance for expansion. For this reason, firms must build up cash piles not only to finance future investment but to ensure that they have future cashflows if things turn bad ��� so they are in effect self-financing. This means that rising cash holdings aren���t as predictive of capital spending as they once were.

- Illusory capital constraints. Increasing capacity constraints don���t necessarily boost investment as much as the Bank or OBR has thought. A study (pdf) of a steel mill by Igal Hendel and Yossi Spiegel showed that it doubled production over 12 years with the same plant because every time the mill seemed to be at ���full capacity���, its managers found ways of tweaking production methods to eke out more output. ���Capacity is not well defined,��� they conclude. If this is true of an old economy steel mill, how much more true is it of intangibles-intensive companies that are more scalable? The ���output gap��� might not be a useful idea.

- Irrelevant profits. Profitability has been high recently, according to official figures at least. But this tells us only that past investments have been successful. It doesn���t necessarily tell managers much about the likely success of future, different projects.

- Low wages. Sustained low wage inflation means firms have had little reason to replace workers with capital.

- Learning. In the past, investments have often proved unprofitable. Charles Lee and Salman Arif have shown that rises in capital spending lead to earnings disappointments, in part because firms have underestimated how hard it is to maintain profits while expanding. To the extent that managers have learned from these mistakes, capital spending will be lower now.

None of this is to deny that Brexit uncertainty is depressing investment: we know that uncertainty causes firms to put projects on ice. What it does mean is that there are many other reasons for weak capital spending. Our obsession with Brexit is distracting us from the fact that there are deep structural reasons why British capitalism is stagnating.

February 7, 2019

In defence of prejudice

Jane Martinson writes that John Humphrys ���has been wearing his prejudices a bit too readily on his sleeve.��� Now, Mr Humphrys has his faults. But wearing his prejudices on his sleeve is not one of them. In fact, we all have prejudices; it���s a good thing that we do; and we should admit to them.

By this I don���t mean racial or gender prejudice but simply our pre-existing opinions. My prejudices, for example, include beliefs that: the efficient market hypothesis is mostly right at the micro level; we all are prone to countless cognitive biases; that neoliberalism has failed to stimulate growth; that greater equality of power and wealth would be a good thing; and so on.

Without such prejudices, our opinions would be unduly swayed by every fleeting voice we hear or data point we see. We���d be so open-minded that our brains would fall out.

In finance, a lack of prejudice produces noise (pdf) traders ��� people who mistake mere noise for solid information and so trade unnecessarily. Over time, this will lose them money. If such traders had the prejudice that profit opportunities were scarce they���d trade less and so markets would be more efficient.

A lack of prejudice can lead to illusions. There���s a rare neurological condition in which sufferers believe that family members have been killed and replaced with replicas. A doctor was once talking to one such patient and asked: ���isn���t it unlikely that such a thing would have happened?��� to which the patient replied: ���Yes. I���d never have believed it if I hadn���t seen it with my own eyes.��� A little more prejudice and a little less willingness to believe the evidence would have helped that man. I suspect the same is true for beliefs in conspiracies and the paranormal.

A lot of apparent evidence is weak. It can be noise rather than signal and even academic research is sometimes unreplicable (pdf). Given this, it���s wise to cleave to our prejudice. Marvin Gaye had a point when he advised us to ���believe half of what you see and none of what you hear.���

By ���prejudices��� I do of course mean ���Bayesian priors���. And saying this alerts us to the real problem. It is not that we have prejudices or even flaunt them. It is that we fail to update them properly in light of the evidence. Racial prejudice survives, I believe, because of a failure to respond dispassionately to day-to-day evidence about what black people actually are: Liam Neeson's error was to fail to see that millions of black men had not raped his friend.

What I find unpleasant about Mr Humphrys is not so much that he wears his prejudices on his sleeve but that he seems too incurious to look for evidence that might disconfirm those prejudices. There���s a big difference between saying ���I think Brexit is a good idea: what is the evidence to the contrary?��� (which I think would be tolerable in a BBC interviewer) and simply harrumphing over anybody trying to present such evidence whilst giving a free pass to those who support one's prejudice.

In this, of course, Mr H is not unusual. A lack of updating ��� Bayesian conservatism ��� is common even when people have incentives to avoid it: I suspect it accounts for at least some of the post-earnings announcement drift and momentum effects we see in stock markets. Worse still, there can be counter-updating, whereby disconfirming evidence causes us to actually strengthen our prejudices.

It���s hard to fight these tendencies not to update properly: I���ve suggested ways to do so, but with no confidence that I follow my own advice.

Worse still, these tendencies are not merely psychological. They are social too. Most of us live in our own bubbles and associate with like-minded people, which leads us to reinforce our prejudice and to regard others as mere caricatures: there���s a massive subfield of metropolitan journalism which portrays the white working class as ill-educated and backward. And commentmongers have little incentive to express the open-mindedness necessary for good updating: a willingness to admit you were wrong is not an obviously good career move.

The problem, then, is not prejudice. It���s that there���s a failure to update such prejudices and big psychological and social pressures upon us to stick to them.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers