Chris Dillow's Blog, page 37

October 31, 2018

Halloween, finance and ideology

Our tastes are seasonal. As winter approaches, we eat less salad and fish and more stews, and I for one listen to less swamp pop and more Leonard Cohen and Townes Van Zandt. What���s true of music and food is also true of appetite for risk. This increases in the spring but declines as the nights draw in: for centuries, May Day has been a celebration of hope and optimism whilst Halloween marks fearfulness and anxiety.

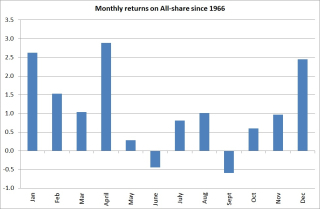

All this is obvious. And it has an obvious implication ��� that stock market returns are seasonal. As the nights draw in and anxiety rises, prices fall too far to levels from which braver investors are well-rewarded for taking risk. And as the nights get lighter in the spring, so prices rise as optimism increases. This year���s events ��� with markets surging in April and May and falling in October ��� fit this pattern like a glove.

This helps explain my chart. Shares tend to do well (on average of course) in December and January, because they were too low in the autumn. And they rise strongly in April as optimism increases. That however leaves them over-priced, which means returns in the summer months are mediocre.

But here���s the thing. Mention this to most investors, whether amateur or professional, and they���ll think you a crank. This isn���t for want of evidence. Ben Jacobsen and Cherry Zhang have shown that the ���sell on May Day, buy on Halloween��� rule has worked in almost all stock markets since data began*. I obey this rule myself: I transferred some of my pension from a money fund into an All-share tracker this morning.

There is infinitely more evidence for a Halloween effect in stock markets than there is for the idea that conventional stock-picking works. And yet talk of a seasonal pattern in returns marks one out as a loon, whilst active managers are Very Serious People.

In fact, there���s another example of this. We have tons of evidence that momentum investing works. And yet few fund managers act upon this ��� although there are many ETFs which claim to exploit the phenomenon. Not many tell their clients: ���we���ve bought these stocks simply because they���ve gone up a lot.���

What we have on both these cases is a massive disjunct between what���s credible and what has an evidence base. Halloween or momentum investing have empirical justification but no credibility; conventional active management has credibility but little (pdf) empirical base.

This tells us two things. One is that evidence-based policy-making isn���t necessarily cold technocracy. In finance, evidence-based activity can be a radical challenge to the Establishment.

It also reminds us that finance is ideological. There���s a good reason why there���s so much resistance to the Halloween and May Day indicators. Fund managers are selling an image. They want to pretend that they are sober hard-headed men who can be entrusted with out money. Stock market seasonality undermines this self-image by showing that their decisions are swayed not merely by cold facts but by the same atavistic swings in sentiment to which stone age men were prone.

As Alasdair MacIntyre wrote in After Virtue, claims to expertise are also claims to power. Sometimes the facts undermine those claims: It���s for this reason that there���s as much hostility to the Halloween indicator as there is to index funds. As Upton Sinclair famously said, ���it is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.���

* Yes, the effect is larger in the northern hemisphere than south. In New Zealand there���s no difference between returns from Halloween to May Day and from May Day to Halloween. And in Australia the difference is a below-average two percentage points. We���d expect some positive difference simply because markets are globalized, so Aussie stocks are pushed up and down by northern ones.

Another thing. You might think that investors should by now have wised up to seasonality, and thus eliminated it. They obviously didn���t do so this year. And there might be a reason why not. Think of stock markets as being like Keynes��� famous beauty contest. The more aware people become of seasonality, the more they might worry in the autumn that others will become anxious. (Or worry that others will worry that others will worry, and so on). If so, they���ll drive prices down even if they themselves don���t feel nervous. Equally, they might buy in the spring in the hope that others will have seasonal risk appetites. In this way, knowledge of an apparent anomaly can cause it to persist or even increase.

October 28, 2018

Not debating diversity

Was Mill right? This, ultimately, is the question raised by the argument over whether centrists should debate with rightists whether diversity is a threat.

Mill thought that:

[Mankind���s] errors are corrigible. He is capable of rectifying his mistakes by discussion and experience. Not by experience alone. There must be discussion, to show how experience is to be interpreted. Wrong opinions and practices gradually yield to fact and argument: but facts and arguments, to produce any effect on the mind, must be brought before it.

This wasn't wholly wrong. If he were to return to us today, Mill would probably be impressed by our progress since his time on attitudes to (for example) religion and women���s rights: the latter weren���t achieved by terrorism alone. And even during my adult life, we���ve seen a decline in racism and homophobia.

But. But. But. There are big dangers with debating diversity. One lies in the mere exposure effect. By treating the claim that diversity threatens the west as a legitimate issue, we risk making it respectable. In this way, racists come out of the margins and into the mainstream. It���s for this reason that Richard Dawkins refuses to debate with creationists.

Another problem is that very few of us are rational Bayesians. Instead, when confronted with contrary evidence, we double down on our priors. And we tend to be much more sceptical about opposing evidence than supportive evidence. Even the most rational debate can therefore lead not to rectifying mistakes but to attitude polarization. This was first pointed out (pdf) back in 1979 by Charles Lord, Lee Ross and Mark Lepper. They showed people mixed reports on the effects of the death penalty. They found that, after reading these reports people who supported capital punishment became stronger in their support, whilst opponents of the death penalty also became more dogmatic. I���m not sure that events since then have shown that their finding was an isolated instance. The "marketplace of ideas" does not always select for the best.

Yes, some people can be persuaded by single debates. But these tend to be those who were open-minded to begin with, rather than partisans.

All this would be true even if racists and near-racists were debating in good faith. Many, however, are not. You can���t debate with liars.

In this context, I fear that centrists are committing an old error, a version of the Wykehamist fallacy. This is the tendency to believe that their interlocutors are, at bottom, good chaps who are amenable to reason because they went to the right schools (as, in fact, many actually did).

You don���t need to disprove ideas ��� assuming such a thing can be done ��� to defeat them. You can marginalize them by ignoring them instead.

In saying this, I���m not arguing for infringing freedoms of speech. Just because you don���t share a platform with someone or give them prominence in other ways does not mean you are denying them rights to free speech. I���m not invited to write columns for national newspapers or to address student unions, but my rights are not thereby infringed in any way. The same should be true for anti-immigrationists.

So far, all I���ve said rules out debating with anti-immigrationists as equals but is compatible with us arguing in blogs and newspaper columns that diversity and immigration are good things.

There are, however, two dangers with doing even this.

One is that it might commit a framing error. Framing the immigration issue in terms of the question ���is diversity a threat?��� begs the question. It assumes that we collectively have a right to reduce diversity by excluding others from our society. But as Chris Bertram has so ably shown, this is not necessarily the case.

In fact, though, I have another problem here. It���s about opportunity cost. If we are debating diversity, we are not debating other things. This matters, because an under-rated facet of political power is the ability to decide what gets onto the agenda. The more we debate immigration, the less time we devote to debating the failings of contemporary capitalism. In this sense, doing so serves a reactionary function, by taking debate about radical progressive social change off the agenda. I���ll leave others to speculate upon whether, for centrists, this is a bug or a feature.

October 25, 2018

Our feeble intelligence

I don���t have cancer. I know most of you don���t give a damn about this, but it highlighted for me an under-appreciated fact - of just how limited a role intelligence plays in our life.

A week ago, I had a slightly alarming symptom I hadn���t experienced before. I thought it might be a side-effect of some eye-drops I���d been prescribed the day before, so I rang the doctor, expecting to either get the prescription changed or be told not to be such a big jessie. Instead, I was sent to hospital to test for a form of cancer, where I got the all-clear yesterday.

When the doctor told me there was a very tiny chance it could be cancer I didn���t hear the words ���tiny���, or ���chance��� or ���could���. All I heard was CANCER. Nor was I comforted by statistics on high survival rates. Instead, I went the full Jacques Brel.

A bit of me knew this was irrational. Bayes��� theorem told me there was indeed only a tiny chance of cancer. My prior probability of having cancer was slim (no other symptoms, no family history) and I had little reason to substantially update this: my one symptom was, I knew, compatible with many benign possibilities.

But what use was such reasoning?

Fuck all.

Intellect told me to heed the words of the Great Man:

Fear is in your head, only in your head

So forget your head and you'll be free

But I couldn���t. My rational mind was impotent against my primal fears. It could not tame the beast in me. My little words were lost. There���s a huge gap between having intelligence and using it sensibly. Between thought and expression lies a lifetime.

There are of course countless examples of this sort of thing. Heightened emotions - anger, joy or fear ��� can cause us to take more risk than we otherwise would. Sadness can cause us to make short-sighted financial decisions. And whilst my judgment was distorted by fear, others��� can be warped ��� especially in financial matters - by wishful thinking. In still other contexts such as investments or corporate takeovers intellect can be over-ridden by hubris (pdf) and overconfidence. In yet other cases, poverty reduces IQ by depleting cognitive bandwidth: you have to take so many decisions to get through the day that there���s little bandwidth left for thinking.

IQ alone, therefore, is feeble. It can be weakened or side-lined by passions, misjudgement or ill fortune.

To be useful It must be allied to something else. In the workplace, these somethings are soft skills. In the cases I���m considering, though, they are something else - self-control. You all know this from university: the best degrees go not necessarily to the most intelligent, but to those with the discipline to revise. When James Buchanan was asked the secret of success, he answered: "keep the ass in the chair".

The ancient Greeks called this phronesis ��� an ability to apply intelligence properly in the appropriate situation. Not only does this require emotional control, but it also requires an ability to adapt to different situations. Sitting here at my desk in a state of calm, I���m intelligent enough. Put me into unfamiliar surroundings where I���m emotionally aroused and I���m an idiot.

At risk of sounding solipsistic or of committing the false consensus error, I suspect I���m typical. Very few of us have phronesis. People of great ability in particular contexts often behave stupidly in others. Think of Vicky Pryce going to prison because anger overwhelmed her intellect, or Bobby Fischer, William Shockley or James Watson being ostracised because they couldn���t shut up, or the countless businessmen led by overconfidence into terrible decisions. (One of the most tragic examples here was that of Jimmy Donley, one of the greatest singer-songwriters of all time who committed suicide in poverty and obscurity).

What���s true of individuals might also be true of whole societies. A nation might be well-stocked with people of ability, but this will avail it little if those abilities are diverted into finance, rent-seeking or soulless drudgery. Nations, as well as individuals, need phronesis.

This, though, isn���t my main reason for writing all this. We hear all the time about people ���battling��� cancer. What we don���t hear so much are the thousands of everyday stories of tests being negative. Through the availability heuristic, this increases our fears of having cancer. I hope this story helps redress this imbalance.

Also, being confronted, even irrationally, with one���s mortality forces one to realize what���s important. Hence the links.

October 23, 2018

Echo chambers: a defence

It���s become fashionable to decry ���safe spaces��� and echo chambers and to call instead for cognitive diversity. Instinctively, I agree: cognitive diversity is one counterweight to the tightly bounded knowledge and rationality that afflict us all.

In this context, then, I���m pleased to see a recent by Ole Jann and Christoph Schottmuller which defends echo chambers.

To see their point, consider what happens when a rightist says a government can���t raise much money merely by taxing the rich. Leftists reply: ���you���re just a shill for the rich. Who fnds you?��� A useful message is therefore ignored. Imagine then we are segregated into echo chambers of left and right, and a leftist says the same thing to a leftish audience. Because s/he cannot be dismissed as a shill, the same message is taken seriously. Worthwhile information thus enters leftist thinking.

There are many examples of this. If CNBC says something disobliging about Trump, it���s ���fake news���, but if (ex hypothesi!) Fox were to do so, it���d have credence with Trump voters. And whereas Jacob Rees Mogg���s diatribes against the EU are ignored by Remainers, criticism of the EU (some of which is warranted) would be taken seriously if uttered by Remainers.

In these ways, echo chambers can actually promote worthwhile discourse by filtering out comments that���d not be taken seriously because they are discredited by association with our opponents, whilst giving proper credence to similar comments coming from like-minded people.

Jann and Schottmuller say:

Segregation into small, homogeneous groups can be a rational choice that maximizes the amount of information available to an individual. In fact, homophilic segregation can be efficient and even Pareto-optimal for society

There���s another way this can be true. If we know we���re speaking among friends, we can be more candid. ���Safe spaces��� can free like-minded people to express sentiments they would otherwise repress if they feared they���d be exploited by their opponents. The model here is perhaps the Chatham House rule, which allows speech to be reported outside as long as it isn���t credited to a particular person. This frees people to speak more freely than they otherwise would. ���Safe spaces may provide opportunities to communicate that would otherwise not exist��� say Jann and Schottmuller.

Now, there are caveats here. All this takes for granted that there is sharp polarization. It would be better if there weren���t and that we could speak freely and credibly across divisions. Given that we cannot, however, echo chambers might be a way to improve communication and to get messages across that would otherwise be ignored.

Also, this requires that there be some degree of diversity within the chambers. If people were to endlessly split and create new echo chambers after every slight disagreement ��� as the People���s Front of Judea and some Trotskyites have done ��� then information is lost anyway.

The issue here is crucially important. In a polarized world, how can we best promote credible and high quality political communication? I���m not sure if Jann and Schottmuller are right that echo chambers really are the answer ��� although I welcome their challenging of my priors. But theirs is a much more useful intervention than partisan mythologizing about threats to free speech.

October 16, 2018

McVey's Rumsfeld assumption

When she was told yesterday that some Universal Credit victims were being driven into prostitution, Esther McVey replied:

Tell these ladies that now we���ve got record job vacancies ��� 830,000 and perhaps there are other jobs on offer.

This, I suspect, is an example of a longstanding and widespread error on the right.

I don���t mean merely the failure to see that what���s possible for one person cannot be possible for all. Even if every unemployed person were to magically fill one of the 832,000 recorded job vacancies, there���d still be 531,000 unemployed and a further 1.9 million people out of the labour force who���d like to work.

Instead, she���s committing what we might call the Rumsfeld assumption. He famously said ���people are fungible. You can have them here or there.��� But this is not true in the labour market. Just because there are lots of vacancies, it does not follow that the unemployed can fill them. If vacancies are for bricklayers or software writers, an unskilled woman will be unable to fill them. People are not fungible. They cannot move to any job that���s available. Each unemployed person is slightly different from the next, and each vacancy slightly different. What matters is that the two match up. Rightists under-estimate this problem. Take three examples of this:

- In 1981, Norman Tebbit told the unemployed to get on their bikes and look for work. He under-estimated the fact that it was difficult for jobless manufacturing workers to adapt themselves to the (few) new jobs that were available.

- During the miners strike, Patrick Minford supported pit closures on the grounds that the unemployed miners would find work elsewhere. Generally, they didn���t.

- Some Brexiters today claim that any jobs lost in exporting to the EU will be compensated for by new jobs in ��� I dunno ��� exporting to Discworld or Narnia.

In all these cases, the right over-estimate fungibility. They under-estimate the amount of sand there is in the wheels of the market mechanism, and so under-estimate market frictions. Ms McVey is following a long tradition. Here, for example, is John van Reenen and colleagues on Economists for Free Trade:

Minford uses a 1970s-style trade model in which all firms in an industry everywhere in the world produce the same goods and competition is perfect. There is no product differentiation ��� a German-made car is identical to a Chinese-made car. Importantly, trade does not follow the gravity equation ��� everyone simply buys from the lowest cost producer.

In other, words, Minford���s world is one in which everything and everyone is fungible. But they are not. Just as some leftists have a unrealistically utopian vision of how socialism works, so some rightists are too utopian about markets and thus about our ability to adapt to disturbances such as to aggregate demand or trading rules. It is no coincidence that support for Brexit and faith in free markets are so correlated: both derive from the same dubious assumption.

October 14, 2018

Brexit, Marxists & the state

Was Marx wrong? This is the question posed by Brexit.

I���m prompted to ask by this from the government���s advice to business on what to do about a no-deal Brexit:

UK companies and limited liability partnerships that have their central administration or principal place of business in an EU member state may wish to consider whether they need to restructure to satisfy the requirements for incorporation in that EU member state.

Faisal Islam says this is the ���first time in history a UK Govt [has] effectively suggested shifting HQs out of UK.��� We���ve gone from Johnson���s ���fuck business��� to ���fuck off business���. Brexit threatens even worse than prolonged slower growth than we���d otherwise have.

This challenges Marx. He thought ���the executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.���

Now, there���s tons of evidence for this far beyond the state���s role in protecting property: state education prepares workers for capitalist drudgery; the welfare state helps to stabilize demand whilst incentivizing people to enter the labour market; and under Thatcher and Blair, a big part of economic policy was aimed at attracting businesses and maintaining confidence.

But no more. Brexit is antagonistic to the interests of capitalists. How, then, can we maintain Marx���s view that the state is a means of promoting the interests of capital?

One possibility is that the interests of capital do not consist merely in high and rising profits. They also require that capitalism be seen as sufficiently legitimate that it can persist without grievous unrest. Because egregious exploitation and inequality would undermine its legitimacy there is therefore a role for the state to impose some progressive taxation or labour regulation. Sometimes, capitalists must be saved from themselves; it is their collective interest that matters, not that of individual spivs.

I���m not sure, though, that this is relevant to Brexit. Granted, backtracking from Brexit might undermine the legitimacy of the state in the eyes of some. But it wouldn���t delegitimate capitalism. And whilst it might provoke civil unrest, this probably wouldn���t be so great as to cost capitalism more than would a hard Brexit.

This leaves us another possibility, described by Ralph Miliband ��� that the state has relative autonomy. To borrow a neat analogy (pdf) from another discipline, think of the relationship between capital and the state as being like that between a woman and her dog on an extendable lead. In the short-term, the dog can run a long way from his mistress and do all sort of damn fool things. But ultimately, it usually* gets dragged back into line. Chile in the early 70s, France in the early 80s and perhaps the Tsipras government in Greece more recently are examples of this.

Brexit could fit this pattern in one of two ways. One way would be for us to end up with a ���Brexit in name only��� ��� if economic chaos, or just warnings thereof, cause a backtracking from a hard Brexit. Whether this happens via a general election or ���people���s vote��� is not important in this context.

But there���s another way. With even a smooth Brexit likely to depress longer-term growth, it���ll be more imperative than ever for governments to attract capital and maintain confidence**. In this way, capital���s hold over the state will strengthen; if Brexiters weren���t so stupid, I���d suspect this was their motive.

All this, however, leaves Marxists with a problem. If any policy whatsoever could be seen as examples of promoting accumulation, sustaining legitimacy or of relative autonomy, what might represent refutation of our theory of the state? Does this just become an unfalsifiable theory?

I don���t think so. The theory predicts that where there is a choice between promoting human flourishing and the interests of capital, the state will eventually opt for the latter. This prediction can be refuted by events, though it rarely is ��� but this is another story.

* In my picture, the dog runs to its death. Some of you might think this undermines my metaphor, others that it strengthens it.

** Fiscal policy is not the issue here. MMTers are right to say the state can borrow as much as it wants, subject only to an inflation constraint. But this doesn���t alter the fact that tax and industrial policy must sustain profits.

October 11, 2018

Adam Smith's two economies

Adam Smith thought there were two economies ��� meritocratic for the poor and powerless and anti-meritocratic for the powerful:

In the middling and inferior stations of life, the road to virtue and that to fortune, to such fortune, at least, as men in such stations can reasonably expect to acquire, are, happily in most cases, very nearly the same. In all the middling and inferior professions, real and solid professional abilities, joined to prudent, just, firm, and temperate conduct, can very seldom fail of success���The good old proverb, therefore, That honesty is the best policy, holds, in such situations, almost always perfectly true. (The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Part I, Sec 3, Ch 3)

But:

In the superior stations of life the case is unhappily not always the same. In the courts of princes, in the drawing-rooms of the great, where success and preferment depend, not upon the esteem of intelligent and well-informed equals, but upon the fanciful and foolish favour of ignorant, presumptuous, and proud superiors; flattery and falsehood too often prevail over merit and abilities. In such societies the abilities to please, are more regarded than the abilities to serve.

This fits the theory of a friend of mine. He says that further up the hierarchy one goes, the longer it takes to identify merit, and so the more chance shysters and bluffers have of thriving. You can spot immediately whether someone is capable of sweeping a factory floor, but it takes longer to discover whether they can manage the factory.

Which raises the question: how extensive is the anti-meritocratic economy? Karen Bradley���s recent admission to being clueless about the province���s politics before she became Northern Ireland secretary was merely the latest and most egregious reminder that in politics merit and abilities are not always decisive to preferment.

And since Smith���s time, we���ve seen the rise of celebrity culture ��� a whole sub-economy of media and entertainment where abilities to please (and dumb luck) produce Adler superstars (pdf), people whose success rests upon simply being talked about. Boris Johnson and Kim Kardashian have much in common in this respect ��� the difference being that one has a massive arse and the other is a massive arse.

It���s easy to believe the same is true near the top of corporate hierarchies. Top managers often prefer to hire men in their own image ��� partly because they are more likely to trust them. This gives (pdf) us the Peter principle ��� that people are promoted to their level of incompetence ��� and the Dilbert principle, that duffers are more likely to be promoted. And their charm and deceitfulness mean that psychopaths are over-represented in top jobs.

All this is compatible with evidence that there is a ���long tail (pdf) of extremely badly managed firms��� with low productivity (pdf): this is what we���d expect if managers are promoted on factors other than ability. (And no, the wheels of competition don���t grind so finely as to swiftly eliminate such laggards.)

In this context, a new paper (pdf) by Andrew Oswald and colleagues challenges my priors. They estimate that only around one-eighth of workers in Europe has a bad boss ��� fewer than one would expect if ; flattery and falsehood too often prevail over merit.

Perhaps, though, the question here is not merely about numbers. Instead (as is often the case) it is about mechanisms. Are the mechanisms that select for merit and abilities rather than flattery and falsehood really as extensive as they should be? And if not, how can we change this ��� assuming of course that we want to?

October 9, 2018

Our insular culture

There are only three economies in the world ��� the UK, US and Venezuela.

Or at least, this is what you���d think listening to the recent reaction to Labour���s plans for nationalizing utilities and more worker say in corporate governance. Rather than see these for what they are ��� steps towards European-style social democracy ��� many on the right greeted them with shrieks of ���Venezuela!!���.

This reflects a longstanding and paradoxical defect in British (English?) political discourse: that although Brexit dominates our politics our knowledge of European polities is near-zero, and certainly not strong enough to form obvious reference points. It���s not just the right that is guilty here. So are leftists. Whenever free marketeers propose reforming the NHS, they immediately invoke images of dystopian American healthcare rather than, say, the Swiss or German systems.

Our ignorance of Europe takes countless very sensible questions off the agenda such as: why is the Finnish education system so good? What can Norway���s experience tell us about the case for a sovereign wealth fund? Why do the Netherlands and Germany have such low youth unemployment? How might we improve vocational education or support SMEs? How best can we design a welfare state that minimizes poverty without greatly diminishing work incentives? And so on.

One of the basic principles of good management is that one should learn from best practice. The absence of Europe from UK politics means we don���t do this. Our political culture imports the worst from corporate management ��� such as leadershipitis and PR bullshit ��� but not the best.

This lack of Europe helps entrench another baleful aspect of our political culture, which we saw during the party conference season ��� an over-valuation of the merits of speeches. This, of course, reflects our backward-looking and anti-historical mythologizing of Churchill as merely a bellicose rhetorician. In this mythology World War II ��� which is one of the very few referents available to our impoverished political discourse ��� was won by fine words rather than by collective organization. The gruntwork of good administration and consensus-building are thus under-rated. Our ignorance of Europe means there���s no counterweight to this.

It���s not hard to find the cause here. We are a monoglot nation. My experience of learning French and German consisted largely of being shouted at by lunatics. Whilst good preparation for the world of work, this did not instil me with Europhilia*. And I���m not as atypical as I should be. Even Gordon Brown, one of our most educated politicians of recent times, looked to the US rather than Europe for his influences.

Herein lies another paradox. Whilst the left considers itself internationalist and centrists flatter themselves to be modern sophisticates, it is the nationalist right which in practice does more to resist this. Links between Farage, Le Pen, Orban, Trump and Putin are perhaps stronger than those between their civilized counterparts.

The media, of course, reinforce all this. The issue here is not merely that lies about the EU have suited its agenda for decades. It���s that reasonably good government is not news. There is therefore silence about policy successes on the continent. In this way, as in others, the news creates a bias against understanding.

I suspect that the net effect of the de facto absence of Europe from political debate is to support neoliberalism by creating the impression that the only alternative to it is economic disaster such as Venezuela is enduring. This, though, is a secondary point. What is more certain is that contributes significantly to bad government and silly political debate.

* It was only quite late in life that I learned that the point of learning French was to better understand the songs of Jacques Brel.

October 6, 2018

The state & profits

Has British capitalism become more dependent upon the state in recent years? I ask because of a curious development in how profits are made.

First, let���s remind ourselves of a basic fact ��� that UK capitalism has evolved in a very different way to the US recently. Whereas the share of profits in US GDP has risen markedly since the 1990s, the UK profit share has fallen since then. Yes, the share soared in the 70s and 80s ��� from what was an unsustainably low point in the mid-70s. But that rise ended 20 years ago. The profit share now isn���t much above what it was in the 50s and 60s. Richard is right to say that labour���s share of GDP has fallen since then, but this is due more to rising taxes on production and to rising rents eating into wages and profits, rather than to a higher profit share.

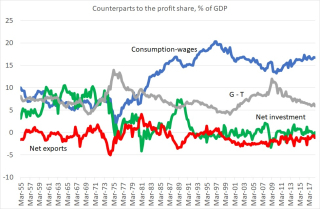

Although the profit share hasn���t changed much except for the slump in the early 70s and subsequent recovery, the components of it have done so.

To see this, we need to manipulate the national accounts a little. GDP is equal to the sum of consumer spending (C), investment (I), government spending (G) and net exports (NX). It���s also equal to wages (W), plus profits (P), plus taxes on production (T), plus other incomes such as rent and those of the self-employed (O). Rearranging these gives us four components of profits:

P = (C ��� W) + (I ��� O) + (G ��� T) + NX.

This equation is intuitive if you think of the circular flow of income. Profits are high (other things equal) if consumption is high relative to wages ��� that is, if workers return their wages to capitalists in the form of consumer spending. They will also be high if capital spending is high relative to other incomes: this is because one firm���s investment is another���s orders. They���ll also be high if government spending is high and taxes low, and if net exports are high ��� that is, if foreign demand for UK goods and services is strong.

My chart plots these four components as a share of GDP since the ONS���s quarterly data began in 1955: they are simply a rearrangement of the data in tables C1 and D of the quarterly national accounts. If we add the four lines together, we���d get my first chart.

And here���s the strange thing. Except for net exports, which have been small and quite stable, these components have changed quite a lot.

Take first the consumption-wage element. In the 50s and 60s this typically represented around one-third of the profit share. It fell in the mid-70s, largely because the savings ratio rose; in effect, workers no longer gave capitalists back so much of their wages in the form of consumer spending. This, along with the fall in net exports as a result of higher oil prices, was the main reason for the profit squeeze then.

Since the mid-70s, however, consumption minus wages has risen markedly, so it is now by far the biggest component of the profit share. In part, this reflects a fall in the savings ratio. One reason for this is that the fall in inflation after the mid-70s reduced uncertainty. Another is that credit liberalization in the early 80s allowed workers to spend more, relative to their wages, than they did before. Also, of course, non-workers spend money as well as workers. Increased pensioner incomes since the 70s ��� the near-elimination of pensioner poverty ��� has raised consumption relative to wages, as more recently did the introduction of tax credits.

That said, C ��� W has declined since the mid-90s because the employment rate has risen. Ceteris paribus, this tends to squeeze the profit share simply because capitalists now have to pay more of their consumers ��� although of course they get a share of a bigger pie. Even after this decline, however, C ��� W is much higher than it was in the 50s and 60s.

Turn now to our second element, G ��� T. This is government consumption plus subsidies minus taxes on production. This tends to be counter-cyclical, supporting profits in bad times such as the mid-70s and 2008-09 but giving less support in good. Even now, however ��� after years of austerity ��� it is much the same size as it was in the 60s. This is because government consumption, in current price terms, is a slightly bigger share of GDP which offsets higher taxes on production.

Now, here���s the big thing. Look at I ��� O. It varied between 5% and 10% of GDP in the 60s, slumped in the 70s and has been around zero ever since except during the Lawson boom.

This has tended to squeeze profits partly because more revenues are going to landlords: Ricardo had a point when he predicted that rising rents would tend to squeeze profits. It���s also because investment has fallen as a share of GDP: this hit 20% in the late 60s but has been 16-17% lately. This squeezes profits simply because one firm���s capital spending is another���s order book. As Kalecki said, capitalists get what they spend.

If we put these trends together, the conclusion is that capitalism is less self-sustaining that it used to be. Profits are more dependent upon state intervention ��� not just government consumption but also policies to ensure that consumption stays high relative to wages such as payments to pensioners and tax credits. Meanwhile, the private sector is doing less to support profits; investment is lower and rents higher.

Put this another way. We can imagine a healthy, vibrant capitalism in which investment is high and profits high as a result and so the system in not so dependent upon state help. And we have to imagine such a system because it is a long way from the one we actually have.

This is not to say that the state has become more interventionist despite the pretence that neoliberalism is a free market ideology. It���s just that the nature of intervention has changed. During the golden age of capitalism, the implicit assurance that the state would ensure full employment and high demand encouraged firms to invest heavily.

Perhaps instead the point is that capitalism has almost always been dependent upon the state: as William Ashworth���s new book describes, the industrial revolution was the result of an activist government. Free market capitalism is a myth now, and usually has been.

October 3, 2018

What counterfactuals (don't) tell us

Imagine if Labour had won the 2015 general election. What would the country look like now?

We���d probably have had less austerity and therefore higher incomes and perhaps higher interest rates. House prices might be a bit lower, but still unaffordable for many young people. The rich would probably be taxed a bit more and whilst there would have been no ���hostile environment��� policy there would be migration controls.

Much of this, though, is uncertain. What there would certainly be, though, is lots of moaning. The left would still be complaining about inequality, slow wage growth and under-funded public services, and the right about high taxes and the nanny state. And of course, there���d be complaints about the low-levels scandals and incompetences that are an inevitable part of even tolerably decent governments. Gordon Brown was massively criticized (often rightly) whilst he was Prime Minister even though in retrospect he looks like a political giant compared to who followed him.

And there���s one thing there wouldn���t be ��� relief. Nobody would be saying today: ���For all his faults, at least Miliband hasn���t given us a chaotic Brexit; the lower incomes that result from a weaker pound; and harsh austerity.��� Nor would anybody be saying: ���I���m alive today because Labour didn���t extend Tory cuts.��� And nor would those centrists who today are bemoaning Brexit be celebrating Miliband saving us from it: they'd be complaining about something else instead.

The point about counterfactuals is that nobody sees them. This trivially obvious fact has (at least) two implications.

One is that we don���t praise governments sufficiently for avoiding really bad outcomes. Leftists, for example, don���t give New Labour enough credit for simply not being a Tory government. We should judge governments not just by what they do, but also by what they don���t. One of the great achievements of a Miliband government would have been the non-policy of not having a Brexit referendum: that, remember, was an attempt to exorcise the Tories��� neuroses; it was not a priority for Labour. (Similarly, one of the great successes of the Wilson government of 1964-70 was that it kept us out of the Vietnam war).

The other is that governments are insufficiently criticized for policies that impoverish us relative to a plausible counterfactual. Simon estimates that fiscal austerity has cost ��10,000 per household, compared to what we���d otherwise have. But nobody feels this as a deprivation in the way they would a ��10,000 bill they could see. Equally, even if Remainers are right and Brexit does make us worse off than we���d otherwise be, few people will experience this as a direct loss. There���ll be no Jim Bowen in 2030 inviting us to look at a more prosperous economy and telling us ���here���s what you could have won.���

Perhaps, though, there���s something else here. Our counterfactual mediocre-ish Miliband government would be copping lots of flak even though it would be vastly preferable to what we have. This tells us that we cannot judge the quality (or not) of a government by the amount of criticism it attracts, not least because so many hyper-ventilate about the smallest mis-step. Pundits are noise, not signal.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers