Chris Dillow's Blog, page 39

September 5, 2018

Prosperity and Justice: a review

I confess I approached the IPPR���s report, Prosperity and Justice, with low expectations. I feared it would be yet more bland technocratic centrism. I was wholly wrong. It gets to the heart of our economic problem ��� that inequalities of power are impoverishing millions of us:

We have to rebalance the relationships of power which currently exist between different actors in the economy. A major part of the sense of injustice that is so widely experienced across the UK today is the lack of control people feel they have, both their own economic circumstances and those of the country as a whole. That sense of powerlessness reflects something real. Within firms, too much power is concentrated in the hands of management, and too little is held by workers. Hierarchical governance models hold back productivity improvement and the spread of workplace innovation, and hold down wages and working conditions.

This is wonderful stuff. And there���s so much more to love: the stress upon the need for stronger trades unions; the correct claim that a fairer economy is a stronger economy; the stress placed upon bad management; recognition that redistribution of income is not enough; calls for a land value tax and tax on lifetimes gifts; and demand for stronger competition policy.

That said, there are some things I don���t like. I���m not sure that short-termism in boardrooms is a problem (I���ll say why tomorrow); or that monopoly power really has increased as much as they claim; and I���m wary of giving the Bank of England a dual mandate to target both unemployment and inflation.

Also, I���m not sure the report is sufficiently awake to some trade-offs. For example:

- Between stronger competition policy and investment. The ���open markets��� the IPPR rightly calls for conflicts with its desire for higher investment. Why should firms innovate and invest if they fear their profits will be driven down from competition from new entrants?

- Between worker say and automation. Greater worker voice might create opposition to labour-saving innovations.

- Between a higher minimum wage and incentives. A higher NMW would further squeeze differentials between the low-paid and the slightly better-paid, which might deter some from incurring the expense and hassle of training or changing job.

None of this is to say the IPPR is wrong ��� just that there are conflicts between good things.

There are also at least a couple of areas where we need more detail.

One concerns fiscal policy. The report says:

Higher wages prompt improvements in productivity. When workers are cheap, firms have little incentive to invest in new technology or innovate in workplace organisation: it is simpler to meet additional demand with more labour.

This is right. One way to achieve these higher wages is to ensure lasting full employment: it is no accident that productivity growth was strongest in the 50s and 60s. How can macroeconomic policy achieve full employment? (The IPPR omits mention of a job guarantee). And if it can, will firms really respond as they did in the 50s and 60s by investing more? Or might they instead fear a profit squeeze and invest less. Will we return to the 60s, or the 70s?

A second issue is worker control. This can occur at different levels. Workers can help set overall corporate strategy at board level. Or they can raise productivity by deploying their detailed but fragmentary and dispersed knowledge of inefficiencies in production and procurement. For me, the IPPR understate the latter.

But of course, the truth here varies from firm to firm. Which means we need a diversity of modes of worker control, depending on how this can best raise efficiency.

These, however, are quibbles and footnotes. Overall, this report is a very great achievement. Mrs Thatcher, reportedly, once banged a copy of Hayek���s Constitution of Liberty onto a table, declaring ���this is what we believe.��� I hope Jeremy Corbyn does the same for this report.

September 4, 2018

Against moral crusades

The on-going row over anti-semitism in the Labour party raises the question: how could parts of the party, and Corbyn in particular, have gotten into such a damned mess?

It���s not because Labour members have unhappy dealings with the Jews they actually meet. In fact, outside of London and Manchester, the typical Labour member will meet hardly any Jews, and those she meets will almost certainly not inspire any animus.

Instead, the answer lies in the fact that some in the party have for years* adopted the cause of Palestinian rights. There���s some justification for this: Labour should be an internationalist party on the side of the underdog. Palestinians, though, are by no means the only people suffering abuses of their human rights. So too are Turks, Kurds, Syrians, Russians, Iranians and so on. The greater interest that some on the left have in Palestine is, I suspect, due to their desire for a moral crusade - for an issue where there is right and wrong**.

Such an urge is dangerous.

For one thing, the cause is futile. There is no good, feasible solution to the Israel-Palestine issue. In this respect, there���s a big difference with Apartheid. ���End Apartheid now��� was a simple and correct slogan in the 70s and 80s. There���s no such moral clarity about Palestine. For this reason, Jeremy Corbyn���s activism on the issue has achieved pitifully little ��� much less than, say, Stella Creasy achieved in her campaign on payday lending.

The biggest danger, though, is that treating politics as a moral crusade leads you to blame and stigmatize the other side. Of course, there is logically a massive gap between anti-Zionism and anti-semitism. For at least a few fanatics, however, the gap disappears. As Phil says, there are pockets of anti-semitism in Labour.

I suspect this is a manifestation of a wider tendency within Labour, described by Graeme Archer ��� Labour���s belief in its own moral superiority. Just as some (many?) Labour members think the Tories are evil, so some (a few?) think Jews are for their support of Israel���s suppression of Palestinians. The psychological root ��� an urge for causes in which to demonstrate one���s moral superiority ��� is perhaps the same in both cases.

We don���t however, need to see politics as a moral crusade. And given that it leads to sanctimonious divisiveness and even to racism, we shouldn���t. Alasdair MacIntyre was right; people have lost the capacity for moral thinking, and (I���d add) it has become little more than an expression of narcissistic self-righteousness.

There are other ways to think of politics.

We could see it as a means of advancing some groups��� interests ��� which is just what Labour was founded to do. Whilst Jeremy Corbyn was laying wreaths and joining pro-Palestinian marches, the capitalist class was assiduously asserting its own interests.

We could also see it as a way of correcting market failures (for example, the under-supply of innovation or climate change) or of solving collective action problems such as the fact that if we all try to reduce debt we���ll simply all end up poorer.

Yes, I know this sounds technocratic. And technocracy has its own flaws ��� not least of which are the tendencies to deceive itself about its ideological nature and to be insufficiently heedful of bounded rationality and knowledge. Given the choice between technocrats and moralizers, however, I���ll take the technocrats.

It���s long been a clich�� that Labour owes more to methodism than to Marxism. This, however, has come at a heavy price ��� a tendency towards moralizing.

* Though not always. As the late Tony Judt reminded us, socialist Zionism was strong until the late 60s.

** There���s a difference here between support for Hamas and support for the IRA. In London in the 80s, it was easy to be sucked into the latter simply because one was surrounded by countless people of Irish extraction wanting you to support political prisoners ��� and reasonable positions can easily shade into less reasonable ones. Most people, I suspect. faced much less pressure to take sides on Israel-Palestine.

August 30, 2018

What's behind the rising US profit share?

Diane Coyle says the fact that different countries have seen different changes in labour���s share of income in recent years ��� with it falling in the US but not UK - shows that ���institutions are playing a big part��� in driving factor shares. This is true. But it���s only part of the story.

I say so for a simple reason. Imagine aggregate wages were to fall for some reason ��� technical change, globalization, whatever. Would this raise the profit share?

Not necessarily. If every ��1 fall in wages causes workers to cut their spending by ��1, profits would also fall. In effect, what capitalists gain from the wage cut, they lose from a drop in revenues. As Michal Kalecki wrote in 1935:

One of the main features of the capitalist system is the fact that what is to the advantage of a single entrepreneur does not necessarily benefit all entrepreneurs as a class. If one entrepreneur reduces wages he is able ceteris paribus to expand production; but once all entrepreneurs do the same thing ��� the result will be entirely different. (Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy, p26)

A fall in wages might therefore cause a drop in economic activity rather than a rise in the profit share. To understand whether this will happen, we need to know what happens to the circular flow of income.

We can express this by re-arranging basic national accounts identities. GDP is equal to consumption, investment, government spending and net exports: Y = C + I + G + NX. It is also equal to the sum of incomes: wages, profits and taxes on production (plus depreciation): Y = W + P + T + D. Rearranging these gives us an identity for profits:

P = (C ��� W) + (I ��� D) + (G - T) + NX.

This should be intuitive. Profits will rise (ceteris paribus): if consumption rises relative to wages (say because workers save less); if net investment rises (as Kalecki says, capitalists get what they spend); if the government borrows more; and if there���s a big trade surplus (say because import prices fall).

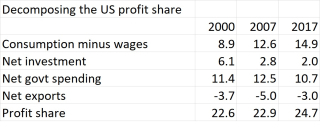

My table applies this framework to the US (based on tables 1.1.5 and 1.10 here*). It shows these four factors as a share of GDP in three years: 2000 (when the profit share was unusually low), 2007 and 2017.

Two big things stand out here. One is that the main counterpart to the rising profit share has been a rise in consumption relative to wages. This hasn���t happened because people have borrowed more; the savings ratio has risen slightly since 2000. More likely, I suspect, it is due to higher spending by business owners.

Also, note that net investment is much lower than in 2000. This suggests the US is in what Marglin and Bhaduri called (pdf) a stagnationist regime, in which a higher profit share is associated with lower investment.

You could interpret these two developments as signalling that profits are being sustained by short-termism ��� consumption rather than by investment.

Now, I know that identities don���t tell us anything about causality. These numbers are entirely consistent with Diane���s point that institutions matter. These can and do put downward pressure on wages. What happens to factor shares, however, also depends upon the behavioural responses to that incipient drop. National accounts identities help identify these responses.

This way of thinking helps explain the IMF���s point, that there���s a massive heterogeneity in developments in factor shares.

Consider, for example, two possible extremes. In one, an incipient fall in wages boosts capitalists��� confidence and hence investment. The upshot could be a boom in economic activity in which the profit share rises but in which the absolute level of wages and employment also rise: this is Marglin and Bhaduri���s exhilarationist regime.

At the other extreme, though, capitalists might respond by cutting investment whilst at the same time consumption stays weak ��� say because workers, fearing further cuts in wages, save more. In this case, we���ll get lower economic activity and even a fall in the profit share.

Both responses are possible, depending upon local and temporary factors such as credit constraints and animal spirits.

In this sense ��� and this is the virtue of Marglin and Bhaduri���s paper ��� general theories about factor shares are insufficient. Instead, as Edmund Burke said: ���circumstances are what render every civil and political scheme beneficial or noxious to mankind.���

* I���ve lumped in the statistical discrepancy with capital consumption. Profits are actually the ���net operating surplus��� which includes rents and self-employment income; this is much higher than corporate profits alone.

August 26, 2018

On wider access to culture

One thing I especially like about Jesse Norman���s Adam Smith is his description of the social and intellectual climate in which Smith grew up. In doing so, he tells us that Smith���s father ��� a ���cultivated and intelligent man��� ��� had a library of 80 books*. Somebody of equivalent prosperity and culture today would of course own many times more.

Fast forward 250ish years to our university days in the 70s, 80s and 90s. You probably had a friend who was a music fanatic: you might have been this man himself**. But he probably owned only around 100 albums. That���s only a tiny fraction of the amount of music available to today���s 20-year-olds.

We have, therefore, vastly greater access to books and music than previous generations did. Which poses the question: how has this changed our culture?

I���m not sure the issue here is simply one of greater cognitive diversity. As Jesse describes, Smith���s contemporaries might have been acquainted with the works not just of orthodox Anglicans but of Rousseau, Hume and Voltaire too. That���s pretty diverse. And until 1746, the strength of Jacobitism led Scotland close to civil war ��� and a civil war betokens a surfeit rather than deficit of diversity.

Instead, one effect is that we now read and listen more widely but less deeply. Well-read men in the 18th and 19th centuries would have re-read and even memorized large parts of the few books they did read, just as our generation played the few LPs we owned to death. Younger people today, I sense, no longer do this to the same degree.

This might help explain what looks like a paradox. The spread of multiple news sources has led to fears that we are becoming Balkanized. Lefties read and believe the Guardian, Canary and Novara; righties Breitbart and the Telegraph. The greater availability of music, however, has had the opposite effect. There are no longer fights between rival musical tribes as there were between punks and skins or mods and rockers***. Young people are less divided on musical lines, perhaps because the greater availability of music means that individual albums (the very word is quaint) mean less to them.

Which raises another change. Back in 1936 Walter Benjamin argued that works of art that are easily reproducible lose authenticity by being separated from their creator and from the space in which they are made; TV is less authentic than the theatre, a recording less so than a live performance. This lack of authenticity is perhaps accelerated if we do not invest so much of ourselves in the work by re-reading and re-listening so much.

People, however, crave authenticity and so seek it elsewhere. It might be that the popularity of live music and festivals, spread of tattoos and support for Jeremy Corbyn all reflect the same thing ��� an urge for authenticity that cannot be so easily found in art.

There might be another consequence ��� a diminution of shared understandings. Until quite late into the 20th century, there was general agreement about what it meant for people to be educated. Today, this is less the case: yes, there is a ���canon��� in many disciplines, but there���s disagreement about what this should be. It is possible for people knowledgeable about books and music to be unable to converse with each other because they���ve few readings and listenings in common.

One reason why there are such heated debates about the state of economics (or about Marxism) is that people have very different understandings of what these are, based upon different readings. Equally, I suspect that some misunderstandings of this blog are founded not just upon my own incoherence but upon readers not having my intellectual referents, such as Roemer, Elster and MacIntyre. The misunderstanding cuts both ways: I got an email in the day job last week which I couldn���t make head or tail of despite coming from an intelligent man, because his frame of reference was so different from mine.

But here���s the thing. Although we lack shared understandings, people want them. This leads to the emergence of Adler (pdf) superstars ��� individuals with no more talent than others but who become famous by luck or good marketing, and this fame then prove self-sustaining as everybody talks about them. Reality TV stars, as well as some authors and singers, fit this pattern. This is one way (of several) in which we see a retreat from meritocracy.

Now, I say all this even more tentatively than usual, based upon little understanding of yoof. Feel free to correct me or to expand. What I���m doing is more asking a question. We know that economic and technical change lead to cultural change. The question then is: how has the greater availability of books and music changed our culture?

* Smith���s father died when Smith was two months old. Like very many great men, Smith was raised in a single-parent family.

** The sexist language is deliberate. This person was almost always male.

*** Another reason for this might lie in another change ��� the greater passivity of young people today, a development which has led (among other things) to the near-disappearance of good English central defenders.

August 23, 2018

Socialism in one country

When I tweeted the other day that the crisis of capitalism consists of a decade-long stagnation in productivity (which has given us falling wages), a wise man replied that this is true only in one country. Which set me wondering: might there be a case for socialism in one country?

Yes, I know the phrase has unhappy connotations. But what I mean is simply that (some form of*) capitalism suits some countries better than others. And perhaps the UK is not one of these.

We can think of this from two different perspectives.

One is the Smithian one, as suggested by Jesse Norman. This says that a healthy capitalism requires particular norms and culture. For example, a society in which there are norms against tax-dodging, rent-seeking or egregious exploitation will have a healthier capitalism than ones in which such norms are weak or absent. Also, for cultural and historical reasons some nations might have a bigger pool of managerial talent or greater entrepreneurial spirit than others. They too will be more suited to capitalism.

Where these conditions are lacking, however, (some form of) socialism might be needed. If some businesses cannot be regulated effectively by self-restraint, market forces or regulation (such as banks or utilities), nationalization might be an option. Where management is bad, worker democracy is needed. And where entrepreneurship is weak, the state must do more (pdf) of the job.

A nation whose ruling class produces people like Johnson, Farage, Cameron or Rees-Mogg is more in need of revolution than one whose ruling class produces better men.

The other is the Marxian perspective. He saw that capitalism was an immense force for economic progress. But, he wrote:

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or ��� this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms ��� with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters.

Some countries have not yet reached this stage of development. In these ��� such as China ��� capitalism is a progressive force. The fact that the UK has suffered a decade of stagnation, however, suggests we might have reached that stage and that we need some changes in property relations if we are to generate further progress. These changes might be in a socialistic direction**.

The appropriate modes of economic organization vary from country to country. In saying this, I���m following Edmund Burke, who wrote:

Circumstances (which with some gentlemen pass for nothing) give in reality to every political principle its distinguishing colour and discriminating effect. The circumstances are what render every civil and political scheme beneficial or noxious to mankind.

These considerations mean it is perfectly coherent to argue that the UK needs more socialism whilst Venezuela needs more capitalism.

Why, then, do so few do this? The answer might lie in a distinction made by Burke as described (pdf) by Jesse. He distinguished between ���embodied��� reason ��� which proceeds from concrete actually-existing conditions ��� and abstract reason which began from theory. Those who give blanket, worldwide support to either capitalism or socialism are perhaps too prone to abstract reason and too little to embodied reason.

* In practice of course most countries are some mixtures of capitalism and socialism (and even feudalism). I���m thinking here of a spectrum between capitalism and socialism, not a sharp distinction.

** In fact, many intelligent free marketeers agree with this. Many of these favour relaxing planning laws to permit more housebuilding or less strict copyright laws. Both are, in effect, curbs on some people���s property rights.

August 22, 2018

Rebuilding commercial society

We need Adam Smith more than ever. That���s the thesis of Jesse Norman���s new book, Adam Smith: What He Though And Why It Matters.

To establish this, Norman first rescues Smith from the caricatures. He was not a free-market headbanger; he did not believe Britain was over-governed, had no doctrine of the ���invisible hand��� and ���did not think free markets always served human well-being.��� Nor was he a shill for the rich. He deplored the tendency to ���admire, and almost to worship the rich���, favoured progressive taxes and thought (as did Marx) that some of the functions of the state worked ���for the defence of the rich against the poor.���

Instead, Norman links the Smith of Wealth of Nations with the Smith of the Theory of Moral Sentiments. The TMS shows how our sense of right and wrong ��� our conscience or what Smith calls the impartial spectator ��� arises from interactions with others. From these we learn what Smith���s near contemporary Robert Burns called the gift to see ourselves as others see us. Our commercial activities are similar. The moral question ���how would others judge my behaviour?��� is similar to the prudential questions: ���How am I coming across to my client?��� What does the customer want?��� All require sympathy ��� a key concept in Smith ��� which we learn from interacting with others.

Market outcomes and social norms alike arise therefore from very similar processes. For Norman, Smith was one of the first theorists of emergence:

Innumerable human interactions can yield vast but entirely unintended collective consequences ��� social benefits, yes, but also social evils.

Markets, then, operate within norms. Norman says:

Markets are sustained not merely by incentives of gain or loss, but by laws, institutions, norms and identities, and without those things they cannot be adequately understood.

In a healthy commercial society (Norman wisely distinguishes this from capitalism) social norms and market processes will reinforce each other well. Norms against cheating and rent-seeking will ensure that markets work well, whilst commercial activity will, in Montesquieu���s phrase (and recently revived by Deirdre McCloskey) ���polish and soften barbaric ways.���

Which brings us to Smith���s relevance today. For Norman, we do not have such a society today. Instead, we have crony capitalism in which:

Business activity loses any relation to, and often clashes with, the public interest;���business merit is separated from business reward. These features then feed off and into a culture in which values of decency, modesty and respect are disregarded, and short-termism and quick rewards come to dominate long-established norms of mutual obligation, fair dealing and just reward.

We need, says Norman, a social, economic and political renewal along Smithian lines which reverses this vicious downward spiral between markets and norms.

Much of this is brilliant. There is, however, another story we can tell here. Smith���s view of the economy as the realm of ���truck, barter and exchange��� ��� interactions between equals ��� is a partial one. There is also Coase���s point (pdf) that lots of economic activity is organized not by markets but by firms. This changes things. As Marx said, most of us leave the ���very Eden of the innate rights of man��� and enter the ���hidden abode of production��� in which there is hierarchy and domination. And these shape social norms as much or more as do barter and exchange.

And they do so less healthily. As Joseph Schumpeter claimed (pdf), the supplanting of the entrepreneur by the bureaucrat weakens market dynamism: I suspect one reason for our current stagnation is that bosses have wised up to the fact that innovation doesn���t pay. What���s more, the characteristics needed to thrive in a hierarchy are not those of sympathy but their opposites: narcissists and psychopaths are over-represented in boardrooms. We have large islands of Stalinism within a market sea. And the characteristics required to prosper within Stalinism are those of Stalin.

Worse still, if we view economies only through the prism of truck, barter and exchange we miss the fact that inequalities of power matter hugely. It is surely no accident that western capitalism best promoted human flourishing during the 1945-73 period, when capitalists��� power was constrained by workers��� power. Norman sees cronyism as a particular pathology of capitalism rather than capitalism itself. But I���m not so sure: cronyism is what we get when capitalists are unconstrained.

Of course, Norman is far too intelligent not to see this. But I fear he doesn���t stress it enough, and that he under-rates the importance of power.

Which is a shame, because greater equality of power might be the way of achieving what Norman (and I) want ��� a healthy commercial society. Perhaps Smith was right that a world in which equals would truck, barter and exchange would lead to one of sympathy and healthy social norms. We need, however, to establish this equality. So yes, we need Smith. But maybe we also need Marx too.

August 16, 2018

For automatic stabilizers

Simon has a good discussion on whether fiscal or monetary policy is better at stabilizing output. I���d suggest, though, that neither is in practice particularly good and that what we need instead are stronger automatic stabilizers.

I say so for a simple reason: recessions are unpredictable. Back in 2000 Prakash Loungani studied the record of private sector consensus forecasts for GDP and concluded that "the record of failure to predict recessions is virtually unblemished" ��� a fact which remained true thereafter.

The ECB, for example, raised rates in 2007 and 2008, oblivious to the impending disaster. The Bank of England did little better. In February 2008, its ���fan chart��� attached only a slight probability to GDP failing in year-on-year terms at any time in 2008 or 2009 when in fact it fell 6.1% in the following 12 months. Because of this, it didn���t cut Bank Rate to 0.5% until March 2009.

Given that it takes around two years for changes in interest rates to have its maximum effect upon output, this means that monetary policy does a better job of repairing the economy after a recession than it does of preventing recession in the first place. And of course, as there���s no evidence that governments can predict recessions any better than the private sector or central banks, the same is true for fiscal policy.

All this suggests to me that if we want to stabilize in the face of unpredictable recessions, we need not just discretionary monetary or fiscal policy but rather better automatic stabilizers.

In this context, I���ve long been attracted to Robert Shiller���s proposals for macro markets. These would allow people vulnerable to recession - such as those in cyclical jobs or with small businesses - to buy insurance against a downturn. I can see why some of you might be sceptical about this: the sort of people who���d sell insurance against recession are the sort who���d be unable to pay out in the event of one. (As with all markets, so much hinges on precise details).

If private sector insurance markets don���t exist, the job of stabilization is better done by government. The most obvious measures here include more progressive taxation ��� so that falls in income are shared with government ��� and higher welfare benefits, both for the unemployed and for those who suffer drops in hours.

There���s something else. Another way to stabilize the economy is to ensure that there are fewer institutions that propagate risk ��� ones that turn small downturns into big ones. This means ensuring that banks are strong and well-capitalized, so that bad loans don���t deplete capital so much as to prevent lending to other companies. Whether this is currently the case is questionable: UK banks capital ratios, for example, are still below the levels recommended by Admati and Hellwig.

It is measures such as these, rather than discretionary macro policy, which perhaps offers better hope for genuinely stabilizing output and jobs.

I suspect, though, that I���m making two more general points here.

One is that macroeconomic stability isn���t just a matter for macro policy. It���s also about the quality of institutions ��� the nature of the welfare state; how far financial institutions propagate risk; whether we have markets to pool risks or not; and so on.

The other is that the inability of policy-makers (and everybody else) to predict recessions is not some accidental contingent feature we can abstract from. A lack of foresight is an inherent part of the human condition. Policy must be based upon this big fact. This, of course, applies to much more than just macro policy.

August 14, 2018

Over- and Under-reactions in politics

You will all have had experience of somebody flying off the handle on the slightest provocation ��� brushing against them in a crowded pub, or pulling out in front of them in traffic. I suspect this everyday behaviour helps us understand politics.

What I mean is that there���s a tendency to over-react to small offences and under-react to larger ones. We see this on both left and right.

On the left, compare austerity to Johnson���s recent Islamophobic remarks. Yes, the latter has led to some deplorable attacks on Muslim women. But austerity has been many thousand times worse. Not only has it made us much worse off than we���d otherwise be, but it also caused Brexit (pdf) with the social divisions and poverty that���ll result, and it might well have caused thousands of deaths to boot. And yet there isn���t thousands of times more anger at Brexit than there has been about Johnson.

And on the right, the abuse Corbyn is getting for the very serious allegation that he���s a terrorist sympathizer doesn���t seem much greater than that Ed Miliband got for eating a bacon sandwich inelegantly*.

The ratio of outrage to cause is large for small causes, but smaller for greater causes.

There are two analogies here. One is with the certainty effect: people pay more to reduce probabilities of loss from 10% to zero than they do from (say) 50% to 40%. The other is with the Easterlin paradox; happiness is much flatter over time than are incomes or political freedoms (pdf). What we have in all these cases are moods being more stable than underlying stimuli: attitudes to risk, happiness or outrage.

Why? There are many reasons why we might over-react to small slights, such as a sense of personal insult, umbrage at the violation of a social norm, or the desire to grab attention. There are also reasons to under-react. One is cognitive; people don���t make connections between social phenomena and so don���t link arid Budget speeches to Brexit or to deaths. The other is a psychological coping mechanism whereby we distance ourselves from horrors. Stalin expressed an uncomfortable truth when he said that one death is a tragedy but a million is a statistic.

There is, however, a problem here. It���s that of the boy crying wolf. If you are always complaining, nobody will take you seriously when you have a genuine grievance. The more noise you make, the less signal there is: if you make a fuss about a Labour leader eating a bacon sandwich, people won���t take you seriously when you make graver allegations. Which might, I suspect, help explain why opinion polls don���t change much from week to week: inattentive voters zone out from partisan complaints even if they might be warranted.

* Yes, one is ridicule and the other is offence, But both are negative affect, expressed with the intention of weakening your opponent.

August 10, 2018

Our broken politics

Many of you believe that our politics is broken. I suspect this is right, in a particular sense.

What I mean is that pretty much all social institutions can be thought of as selection devices. The problem with politics is that these devices are working less well than they used to. Here are five examples of what I mean.

1. Parliamentary candidates used to be selected by mass-membership parties in which an ability to persuade or to build wide support was valued. Today, parties have been captured by fanatics and narcissists who select candidates in their own image; this problem has been exacerbated by the fact that there are bigger rewards on offer outside of parliament, which (at the margin) selects against some able people.

2. Ministers used to be selected as the most able MPs. Today, more premium is placed upon toeing the party line. The wretched Chris Grayling or Liam Fox thus occupy office because they are Brexiters, rather than because of any competence or character.

3. MPs used to see their role in Burkean terms - as being members of a ���deliberative assembly��� exercising independent judgment. In this way, the ���hasty opinion��� of the public was sometimes selected against. Today, with the rise of referendums and conception of politics as just another arena where the customer is king, this conception has declined.

4. We used to think that free debate would select for good ideas and against bad. As Mill wrote:

[Mankind���s] errors are corrigible. He is capable of rectifying his mistakes by discussion and experience. Not by experience alone. There must be discussion, to show how experience is to be interpreted. Wrong opinions and practices gradually yield to fact and argument.

Today, this seems doubtful. People are asymmetric Bayesians. Confronted with opposing evidence, thy double-down (pdf) on their prejudices rather than yield to fact. Debate doesn���t therefore select properly for better ideas. (The BBC���s impartiality between truth and falsehood reinforces this failure).

5. Maybe there was a time when the media selected for intelligence or at least against egregious scumbags. Today, it doesn���t. In the 90s, David Irving was shut out of the public domain. Today, though, he���d have lots of Twitter followers and broadcasters, desperate to attract the viewers and attention that comes from controversy, would no doubt invite him onto their shows ��� as they do with Bannon, Gorka and Farage. This lust for mindless controversy ��� what I���ve called politics as wrestling ��� means that buffoonish charlatans like Johnson get attention whilst decent thoughtful MPs such as Jesse Norman do not. (A lot of the left should also be blamed here for preferring the moralistic posturing of ���calling out��� to engaging with serious ideas.)

Now, I���m not pretending that there was ever a golden age of perfect deliberation. There never was. Politics has always had a share of duffers and crooks. I just suspect that its selection mechanisms are more dysfunctional now than in the past. Bad ideas and bad people are more likely to be selected for rather than against. (This of course is not to deny that there are still some decent people left in politics: there are.)

Our question, therefore, must be: how can we build better selection mechanisms? Paul Evans deserves huge credit for asking just this.

For me, at least part of the answer would be institutions (pdf) of deliberative democracy ��� mechanisms such as citizens juries which consider evidence and which help equalize political power by giving a say to the poor and downgrading the influence of the mass media. Paul Cotterill is right to call for a more Habermasian politics.

Merely saying this, of course, draws attention to the big problem here. Our current broken selection mechanisms serve the rich and powerful very well: why should they take a risk with deliberative, inclusive evidence-based policy-making? Perhaps, therefore, there is a tension between actually-existing capitalism on the one hand and a well-functioning democracy on the other.

August 8, 2018

Labour's Bank of England problem

Despite Jo Michell���s criticisms of him, I fear that Richard Murphy raises an important point here.

To see it, let���s assume Labour were to take power today. There is a pressing need not just for more infrastructure spending but for more current government spending ��� on the NHS, local government, courts, prisons and so on. Let���s say that Labour does raise such spending, and therefore aggregate demand.

The Bank of England would regard this as inflationary. It raised rates last week because it believes ���the UK economy currently has a very limited degree of slack���. A fiscal expansion would eat further into this slack thus prompting the Bank to raise rates to suppress demand.

Of course, the Bank of England might well be wrong to believe this*. But even if it is, rates will rise in response to a fiscal stimulus.

In this sense, Richard is right to say that ���austerity will remain in place���, in the sense that we���ll suffer ongoing weak growth and continued mass unemployment ��� the difference being that it'll be due to tighter monetary rather than tight fiscal policy. And he���s right to say that, as things stand, Labour is leaving Carney & Co in charge.

In this context, the question of financing the extra government spending is a red herring: even if it were accompanied by higher taxes, there would be some rise in rates ��� remember the balanced budget multiplier?

The question is: what to do about this?

One solution would be to remove the Bank���s operational independence or, less radically, to raise its inflation target: doing so might be justified as a means of offsetting the Bank���s bias to over-estimating the Nairu.

It���s easy, though, to see why Labour might be loath to do this. Doing so would invite its critics to invoke folk memories of Labour���s failure to control inflation in the 70s.

It would also be only a temporary fix. Jo has a point when he says:

One doesn't have to sign up to a constant NAIRU to acknowledge that at some point higher demand is going to induce inflationary pressures. I sometimes get the impression this is not sufficiently acknowledged in MMT.

The constraint upon full employment is genuine ��� even if nobody knows for sure where exactly it is. Jo is therefore right to say that fiscal policy alone cannot achieve full employment.

He���s also right to say we need a progressive supply-side policy ��� ways of boosting productivity, capacity and competition to enable the economy to grow without generating so much inflation. It is here that Labour���s attack upon neoliberalism should lie: a national investment bank, worker democracy and even a citizens��� basic income.

But, but, but. It is unclear whether such policies really can do much to boost trend growth. In a famous paper (pdf) John Landon-Lane and Peter Robertson argued that national policies can do little to affect trend growth, and Dietz Vollrath has shown that they can���t increase productive potential very quickly.

This is not to counsel despair. Getting rid of the Tory-Centrist fiscal squeeze would be a good idea; a little higher inflation or interest rates would be no disaster; and lots of supply-side policies such as better education, stronger competition policies and worker democracy are good ideas even if they don���t do much to raise growth.

Instead, we must remember the old Marxian question: how much can policy achieve within the constraints of capitalism? Yes, some of these constraints are illusory (such as capital flight). But some of them are not.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers