Chris Dillow's Blog, page 40

August 7, 2018

Ownership in question

What is the right form of ownership of a company? This is the question raised by Stan Kroenke���s proposal to buy all the remaining shares in Arsenal ��� a move described by the Arsenal Supporters Trust as ���dreadful���.

Viewed through the lens of some conventional economics, the AST���s objections seem misplaced because there are big pitfalls with dispersed ownership which can be solved by concentrating ownership into fewer hands.

One of these is a lack of incentives. If a firm has many shareholders, it accounts for only a small fraction of the wealth of each owner. No owner therefore has a strong incentive to go to the bother of improving the management. There���s a problem of collective action: the costs of doing so are borne by a few active shareholders, whilst the benefits accrue to all owners.

Another is asymmetric information. Outside shareholders often just don���t know enough. They didn���t stop RBS collapsing, for example, because they didn���t realize just how terrible the business was.

For these reasons, the number of stock market-listed firms has been in decline for years ��� as Michael Jensen predicted in 1989.

Kroenke���s plan fits this pattern. So the AST is wrong to object, isn���t it?

No, no, no. The standard objections to dispersed ownership don���t apply in this case. Arsenal���s individual shareholders don���t lack incentives; they have a passionate desire to see the team succeed far beyond their financial interest. Maybe more so than Mr Kroenke who ��� it is feared ��� might use Arsenal as a cash cow to finance his other ���franchises���. Nor is there much asymmetric information: Arsenal���s shareholders get regular (and painful) updates on the team���s performance every few days. That cannot be said of most listed companies.

In fact, there���s a third difference ��� externalities. For many companies, outsiders don���t care whether they succeed or not: when Phones4U went bust, people simply switched to Carphone Warehouse for surly service from spotty youths. That was no big deal. With Arsenal it is otherwise. Right-thinking people who don���t own shares care deeply about their fortunes*.

For these reasons, I think AST is right to want to retain dispersed ownership. In fact, there might well be a case for going further, and favouring fan ownership (pdf) of football clubs.

Of course, the issue here is much wider than the matter of who should own Arsenal. It applies to all companies. There are four issues here:

- Who has skin in the game? More skin should mean more ownership, as it gives you sharper incentives to maximize the value of the asset. This is why there���s a stronger case for fans to own clubs than players: players can and do agitate for transfers out of failing clubs, whereas fans are much more emotionally invested. In the same spirit, it is often workers or sub-contractors who bear the most risk of a company collapsing.

- Who knows the company best? These should own the business as they know best how to maximize its efficiency. It made sense for Richard Arkwright to own a factory because he knew the production process best ��� he���d invented much of it ��� whilst many of his employees were illiterate. Conversely, human capital-intensive businesses such as law firms are often owned by their employees and rarely by outside shareholders. I suspect this is sometimes a case for transferring ownership from outside shareholders to workers.

- How important is the company? Xavier Gabaix has shown that some firms are so important that their failures have macroeconomic implications. And Daron Acemoglu and colleagues show that networks (pdf) matter; firms that are the hub of networks can drag others down with them, whereas others aren���t so important. The failure of RBS, for example, mattered much more than that of Carillion. For some firms, it���s a matter of public indifference who owns them. For others, it does matter. The question of who should own banks is an important policy question. That of who should own fishmongers, not so much.

- Does the market for corporate control work? If it does, then ownership will flow to the people best able to maximize the value of the asset and policy-makers need not worry. Personally, though, I suspect this isn���t the case. Takeovers sometimes fail horribly, in part because they are motivated (pdf) by some cognitive biases. And in other cases, credit constraints or problems of collective action might prevent more widespread worker or consumer ownership.

Of course, the best form of ownership will vary from business to business. There is, however, no assurance that the market will ensure that businesses do get the best owners. Which means that in at least some cases, the question of who should own an asset is a legitimate political question.

You might object to this that efficiency isn't the only ideal and that traditional property rights matter too. Maybe. But as I said yesterday, some bearded guy might have been right to point out that the two might conflict.

* Of course, fans of Sp*rs of Chelsea want to see them fail, but these by definition are not right-thinking people.

August 6, 2018

The robot paradox

���More than six million workers are worried their jobs could be replaced by machines over the next decade��� says the Guardian. This raises a longstanding paradox ��� that, especially in the UK, the robot economy is much more discussed than observed.

What I mean is that the last few years have seen pretty much the exact opposite of this. Employment has grown nicely whilst capital spending has been sluggish. The ONS says that ���annual growth in gross fixed capital formation has been slowing consistently since 2014.��� And the OECD reports that the UK has one of the lowest usages of industrial robots in the western world.

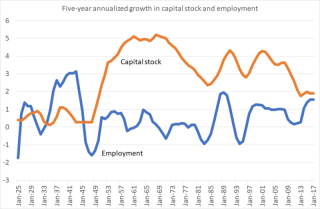

My chart, taken from the Bank of England and ONS, puts this into historic context. It shows that the gap between the growth of the non-dwellings capital stock and employment growth has been lower in recent years than at any time since 1945. The time to worry about machines taking people���s jobs was the 60s and 70s, not today.

Of course, we shouldn���t set much store by the precise numbers here: measuring the capital stock is a fool���s errand. But these data are consistent with other facts. Households are saving less than they used to, which is not what you���d expect if they feared losing their jobs. Companies are still building up cash quickly and borrowing little, and of course real interest rates are low. All this is consistent with low capital growth.

If we looked only at the macro data, we���d fear that people are taking robots��� jobs ��� not vice versa.

So why is investment so weak (a fact which long pre-dated Brexit uncertainty? There are thousands of firms that aren���t investing in new tech, and therefore thousands of potential explanations. Among them are:

- There is, as Bloom and Van Reenen say, ���a long tail of extremely badly managed firms (pdf)��� which lack the confidence or competence to invest in new technology.

- The 2008 recession had a scarring effect upon animal spirits; it raised the fear of future recessions and so deterred investment.

- Fiscal austerity depressed aggregate demand and hence the motive to invest. And in squeezing real wages, it reduced companies��� incentive to invest in labour-saving technology: this was one reason why investment boomed in the 60s.

- Talk of a robot age might be self-defeating, as it increases fears of future competition; why spend ��10m on robots if a rival will undercut you by spending ��5m on better ones in a few months��� time? Maybe firms have wised up to Nordhaus��� finding ��� that innovation doesn���t pay very well except for a tiny handful of firms. (Hendrik Bessembinder has estimated that 4% of firms account for all of the rise in the US stock market since 1926).

Whatever the reason for low investment, we have a genuine paradox here ��� that whilst there���s much talk of a robot economy there is little evidence of it in the data or on the ground. There might, therefore, be a mismatch between the vast productive potential that technology might offer us on the one hand, and the poor performance of today���s capitalism on the other.

Marx famously wrote:

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production...From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters.

One of the neglected questions of our time is: could it be that we have now reached this stage?

August 3, 2018

Diversity: a rightist ideal

The left does not have a monopoly of wisdom - or, if we judge by the row about anti-semitism, any wisdom at all. There is one great truth which, historically, rightists have known better than many leftists. It is that our knowledge and rationality (two different things) are seriously limited.

Hayek, for example, famously based his defence of free markets upon the fact that:

The knowledge of the circumstances of which we must make use never exists in concentrated or integrated form but solely as the dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess.

The economic problem, he said, ���is a problem of the utilization of knowledge which is not given to anyone in its totality.��� In this, he echoed Edmund Burke:

We are afraid to put men to live and trade each on his own private stock of reason; because we suspect that this stock in each man is small, and that the individuals would be better to avail themselves of the general bank and capital of nations, and of ages.

To Hayek, free markets are a means of aggregating dispersed, fragmentary and even tacit information, and hence a way whereby we can avail ourselves of the general bank of knowledge.

We can of course add Michael Oakeshott to this tradition. As Jesse Norman points out (pdf), he too emphasized the limits of individual reason.

What we have here, then, is a powerful intellectual tradition ��� one which I think is validated by the research on cognitive biases inspired by Daniel Kahneman.

Which raises a paradox which I suspect is under-rated. It���s hinted at by Will Davies. For conservatives, he says:

Often the deeper anxiety is that the traditional monoculture of the nation, which dates back more than 200 years, is being questioned by feminists and post-colonial critics. Thus another paradox of the free speech panic is that what gets termed censorship is often quite the opposite ��� namely, the opening up of scholarly debate to a broader range of perspectives.

The paradox is this. If you believe that knowledge and rationality is limited and partial, then it is you who should especially welcome the voices of feminists and ethnic minorities. Their perspectives form part of the ���general bank and capital��� of wisdom of which Burke spoke. Without them, we are trading only upon the stock of reason of old white men ��� which is limited. (I should know: I am an old white man).

Similarly ��� in the spirit of Will���s piece ��� you should also welcome a diversity of mechanisms for revealing wisdom and knowledge. Yes, markets are one way of revealing these. But so too are scientific methods, peer review and academic debate. You should therefore regret the marketization of universities, as it overturns the wisdom of ages which is for them to be part of the non-market system.

There���s something else that might follow from the Burke-Hayek perspective ��� a support for worker coops.

Hayek was right to say that markets are a way of mobilizing fragmentary and dispersed information. But as his LSE colleague Ronald Coase pointed out, markets are often suppressed (pdf) in favour of corporate hierarchies. Such hierarchies might well not be an optimal way of aggregating dispersed information: this might be because of path dependency or because firms suffer a form of bureaucratic capture by top managers*. Instead, it���s possible that one way better using fragmentary information is to give workers more say in how the firm is managed. Doing so mobilizes their knowledge of small inefficiencies. It���s a way of aggregating marginal gains through cognitive diversity.

My support for worker democracy owes less to Marx ��� who wrote little about post-capitalism ��� than it does to Hayek.

My point here is simple. It���s that diversity should be a rightist ideal. If you take seriously Burke and Hayek���s warnings about the limits of our cognitive powers, you should welcome the diversity of perspectives that comes with hitherto silent groups ��� women, workers and ethnic minorities ��� being given a voice.

Which poses the question: why, then, are rightists not championing diversity and coops?

One possibility is that there is a tension here. Ways of harnessing diversity ��� be it worker democracy or giving more voice to minorities - require us to abandon the wisdom of the past. There���s a trade-off between availing ourselves of the general bank of wisdom of ages and of that of the nation. My personal preference is for the latter. So, in fact, was Hayek���s ��� hence his essay, Why I am not a Conservative. Many rightists, however, seem prefer the former. Corey Robin says this is simply because their true attachment isn���t to freedom or efficiency but simply to established hierarchy. I wonder: how would one prove him wrong?

* Competition does not eliminate such inefficiencies. We know this from Bloom and Van Reenen���s work showing that there���s a persistent long tail (pdf) of badly managed firms, and from de Loecker and Eeckhout���s work showing that profit margins (pdf) have trended upwards since the 1980s and are widely dispersed.

August 1, 2018

The Marxist Bank of England

Does capitalism maximize the life-chances of working people? This old Marxian question is the context in which we should judge the Bank of England���s interest rate decision tomorrow.

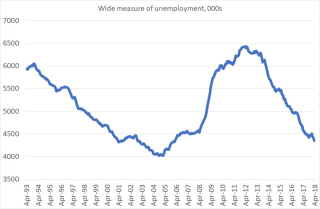

What I mean is that conditions for many working class people are poor. My chart shows one measure of this. It shows a wider measure of unemployment ��� the officially unemployed plus part-time workers who want a full-time job plus the inactive who want to work. There are almost 4.4 million of these ��� over one in ten of the working age population. As Danny Blanchflower and David Bell point out, under-employment is endemic.

Of course, some of this unemployment is frictional ��� employable people who are briefly between jobs. But it also means that hundreds of thousands of the worst-off ��� the unqualified, disabled, those with mental health issues ��� can���t find work. This matters enormously because unemployment is a major source of unhappiness: the jobless are three times as likely to report low well-being as those in work*. In this sense, capitalism is still inflicting misery upon millions.

And not just upon those at the bottom of the pecking order. For the average worker, real wages are still lower than they were before the 2008 crisis. And they are barely growing at all ��� which tells us that unemployment a few months ago was not low enough to significantly push up wages.

Not only are we not seeing meaningful pay rises, we���re not seeing much of what we���d expect to see in a boom. Not many employers are greatly improving working conditions (which are desperately bad for millions) as they should if they can���t attract or retain staff. Nor are they investing much in new equipment to raise productivity: the volume of capital spending is barely growing. The innovations gap of which Simon speaks is still big.

In this context, what would the Bank be saying if it raises rates tomorrow, as most economists expect?

It would be saying that all the above is close to as good as it is going to get for workers: in May, the Bank forecast (pdf) that the narrow measure of unemployment will fall only very slightly over the next two years. It would be saying that mass unemployment is necessary to hold down inflation. And not just mass unemployment, but the things it entails ��� tyrannical bosses, poor working conditions and low productivity for those in work. This is all the more true because it���s possible that a rate rise now would do more than usual to depress employment.

Of course, in a big sense the Bank is not to blame for this. It is not its job ��� and certainly not its job alone ��� to ensure a low Nairu. If it does raise rates, the Bank is just being the messager - the message being that actually-existing UK capitalism is unable to provide decent living standards for millions, and that genuinely full employment is impossible. This is a Marxian message.

Of course, it might be that the Bank would be wrong to raise rates. Personally I suspect that, with wage inflation not yet rising, the Bank can afford to wait before moving. Which means that if the Bank does raise rates tomorrow, it would be more Marxist than I am.

* As Joan Robinson said, the one thing worse than being exploited in capitalism is not being exploited.

July 31, 2018

Lying for Money: a review

Just as they tend to over-glamourize murders, so TV dramas over-glamourize fraud: remember the BBC���s rather good Hustle? In the real world, though, both have something in common; they are squalid crude affairs committed mostly by inadequates. This is a message of Dan Davies��� history of fraud, Lying For Money.

He shows that most frauds fall into a few simple types. There���s the long firm ��� setting up a fake company to borrow money which you run off with; Leslie Payne, an associate of the Krays, was a master of this. There are pyramid schemes, most famously those run by Charles Ponzi but Dan treats us to the story of the Pigeon King too. Then are control frauds, whereby someone abuses a position of trust: rogue traders fall into this type. And then there are plain counterfeiters. My favourite was Alves dos Reis, who persuaded the printers of legitimate Portuguese banknotes to print even more of them ��� so many as to devalue the escudo.

All this is done with the wit and clarity of exposition for which we have long admired Dan. His footnotes are an especial delight, reminding me of William Donaldson.

Dan has also a theory of fraud. ���The optimal level of fraud is unlikely to be zero��� he says. If we were to take so many precautions to stop it, we would also strangle legitimate economic activity. He calls this the ���Canadian paradox���. Fraudsters have, if only briefly, thrived there ��� not least by floating mining stocks. This is because Canada is a high-trust society; fraudsters exploit others��� trust and the fact that dishonesty is the exception. By contrast, in low-trust societies people do business only with those they know well. That means less fraud, but also less business and more poverty. Trust, says Dan, is the basis of a prosperous commercial society ��� but it is also what fraudsters exploit.

If I have a criticism, it���s that Dan doesn���t much discuss the psychology of fraud ��� of how we fall victim to it. He writes:

Fraudsters don���t play on moral weaknesses, greed or fear: they play on weaknesses in the system of checks and balances, the audit processes which are meant to supplement an overall environment of trust.

But is this wholly true? Some people are more vulnerable to scammers than others. I���d have liked Dan���s analysis of why. He doesn���t, for example, discuss Werner Troesken���s fantastic history (pdf) of snake oil salesmen.

Also, perhaps we can extend Dan���s work. He discusses outright criminal fraud. But there are similar types of behaviour which are legal ��� such as selling snake oil in 19th century America. Dan hints at this when he describes the justification for bans on insider trading and other egregious types of market manipulation:

If you stopped robbing people blind with stock pools and takeover rumours, you would attract more of them into the capital markets, to make more money overall by robbing them through trading commissions and management fees.

We can think of fund management fees as a form of legal control fraud; using a position of trust to enrich oneself whilst failing to provide the service implicitly promised. CEO pay also falls into this category.

Similarly, whilst the directors of failing companies such as BHS and Carillion who took millions of pounds in salaries and dividends were not guilty of a long firm fraud, their behaviour was not wholly dissimilar.

And cynics might add that newspaper columnists, think-tankers or politicians are similar to affinity fraudsters; they take money for misleading like-minded people.

The law of course makes a sharp distinction between criminal and non-criminal behaviour: that���s what it���s for. But I wonder whether the distinction is so clear in reality. It���s not just criminals who lie for money.

July 28, 2018

The politics of discovery

Here���s a theory. There are two different ways of thinking about politics and policy which are insufficiently distinguished; we can call them politics as imposition versus politics as discovery.

Most people think of politics as the former: how can I impose my will upon others? We can, however, think of it differently ��� as a discovery process.

This, I think, is what Paul Evans is doing when he calls upon us to rethink democracy. He���s asking: what institutions and practices do we need to discover what people really want? Simple referendums, conducted against the background of an inadequate media, are not the answer.

But it���s not just the political process that is or should be a discovery process. So too are some particular policies.

We lefties are sometimes accused of wanting to impose a system upon the economy. For me at least, this is the exact opposite of the truth. For me, socialism consists in part of creating means of discovering what works best.

Democratising public services, for example, is a way of discovering from workers and users how best to improve them. And encouraging various forms of coops ��� via public procurement, a national investment bank or tax breaks ��� is a way of discovering what forms of post-capitalist firms work best ��� a form of what Erik Olin Wright calls interstitial transformation (pdf). It���s not at all obvious to me that actually-existing capitalism does an unimprovable job of discovering better forms of ownership and control, given credit constraints, path-dependency and capture by a managerialist elite*.

I���d put a citizen���s basic income into this category: the question of the appropriate level, and any add-ons it needs, is one that could be discovered as we go along. It need not, and maybe cannot, be imposed in perfect form from the start.

This isn���t to say that the politics of discovery is purely a leftist exercise. It���s not. Michael Gove���s free schools policy was in this vein ��� a way of experimenting to see what sorts of school work best.

And one under-rated argument for devolution and stronger local authorities is that they would facilitate discovery: if they follow different policies, we can see what works best.

We think of markets as discovery and selection mechanisms (pdf) ��� albeit ones that often don���t work as well as they might. But a healthy political process would have such mechanisms too.

Which brings me to Brexit. Everybody is discussing the Brexit deal with the mindset of the politics of imposition ��� as if the deal will permanently settle in stone our relationship with the EU for ever more.

This of course is to misrepresent human life. Relationships change. The ���transitional period��� won���t end in 2020. It���ll carry on for as long as the UK and EU exist.

This is no mere pedantry. One of the key aspects of good negotiations is to see that agreements can be provisional, not final. Theresa May should be saying to all sides in the Tory party: ���This isn���t the final word. Let���s give this a go. And if it proves to be as bad as you claim, we can change it.��� (Maybe she is saying this in private.) I���ll grant, however, that this is more feasible for hardline Leavers than Remainers, as the EU might not want to renegotiate closer ties with so fractious and febrile a counterparty**.

If there is anything in what I say, it poses the question: why do we hear so much about the politics of imposition and so little about the politics of discovery?

One answer is that political discourse is dominated by those who believe they know the answers, and so don���t need to discover them ��� which is of course a symptom of overconfidence. We do not sufficient self-police and self-criticize our views. And perhaps we lack the mechanisms and institutions to incentivize us to do so.

* It���s odd how some rightists are so keen to point out that state functions are prone to bureaucratic capture and so silent on the possibility that private companies can be too.

** Yes, I know that we Brits tend to under-estimate the extent to which the EU is a rules-based organization (which I think is an argument for the Leave side). But rules can and do change.

July 26, 2018

Not debating immigration

Some new neighbours recently moved in next door to me. They seem nice, but the point is that I had no say whatsoever in the matter. And yet almost everybody believes that, together with my fellow Brits, I have a right to stop people moving into the UK. This is weird. Why should I have a right to stop people moving into, say, London when I have no right to stop them moving next door, even though I don���t care who lives in London but do care whether I have good neighbours or not? And how can a group of people acquire rights that individual members don���t have?

Chris Bertram���s new book Do States Have The Right To Exclude Immigrants? tackles such questions.

His key point, derived from Kant, is:

Claims of right, in order to be other than mere assertions of power against others, have to be justifiable to everyone���nobody should simply impose their will on someone else unilaterally.

Instead, there needs to be an implicit bargain, whereby everybody has a reason to obey the rules.

Such reasoning justifies why I have no right of veto over who moves in next door. My lack of right in this regard is compensated for by the fact that nobody else has a veto over my moving where I want. Most of us think this is a reasonable bargain.

But this doesn���t apply to immigration. Why, asks Bertram, should would-be immigrants respect our claim to exclude them?

The answer is: they shouldn���t:

A world in which states simply assert their right to unilaterally exclude would-be migrants���is a world in which a kind of tyranny is imposed upon the excluded.

He argues that if we were behind a Rawlsian-style ���veil of ignorance��� we wouldn���t agree to draconian restrictions of free movement as they might trap us into horribly oppressive governments or condemn us to a life of poverty: John Gibson at the University of Waikato has estimated (pdf) that migrants from Tonga to New Zealand, for example, earn three times as much as comparable people remaining in Tonga. Behind such a veil of ignorance, he says, we���d pick open borders.

Now, I���m sympathetic to this. Which means I���m not the sort of person who should be reading it. It should instead be read by those who favour migration controls.

I asked myself: how might a reasonable defender of migration controls respond to it?

One possibility is to deny the appropriateness of the veil of ignorance thought experiment. Maybe our nationality isn���t something we can slough off but is instead an inherent part of who we are. Perhaps, as Michael Sandel said in Liberalism and the Limits of Justice, we are ���radically situated subjects��� with loyalties that are deeper than mere contingent accidents.

I would have liked Chris to have done more to tackle this. I myself don���t know what to make of it. It gains credence from the fact that people die for their country. But on the other hand, nations are ���imagined communities��� and, as Chris says, historically quite recent ones: for most of our history, humans have not considered themselves defined by nationality.

My criticism of Chris on this point, however, is minuscule compared to my criticism of our political-media culture. Alasdair MacIntyre complained ��� rightly ��� that we lack the intellectual resources for serious moral enquiry, and also the institutions that would permit it. No, the Moral Maze does not count. The sort of world in which Chris might have been seriously grilled by a Bryan Magee-type is long gone. Instead, ���debate��� about moral questions (not just immigration) is more commonly merely an exchange of self-righteous shrieks and politics merely a haphazrd way of discerning the "will of the people". Much as I enjoyed Chris���s book, I fear it is wasted in this climate.

July 24, 2018

Corbyn's neglected question

Jeremy Corbyn���s speech this morning raises a big question in economics that won���t get the attention it deserves: is there a trade-off between static and dynamic efficiency?

Corbyn wants to use government procurement policies to ���build things here again that for too long have been built abroad��� and objects to the decline of UK manufacturing and growth in cheap imports.

His critics read this as him wanting to roll back the international division of labour. That���s inefficient, As Adam Smith famously noted, it is the division of labour that boosts productivity. Pushed to an extreme, this mentality leads to North Korea or to Mao's ruinous backyard blast furnaces.

Now, these critics might not all be wholly sincere. Many of them have been silent about the fact that capitalism itself has greatly slowed down the international division of labour; world trade growth has been much weaker since the 2008 crisis. And not all them are sufficiently awake to Dani Rodrik���s point that the benefits of that division of labour have been distributed unevenly.

Nevertheless, they do have a point. Corbyn���s plan looks inefficient in static allocational terms.

There might, though, be a defence of it. It���s that supporting manufacturing might provide opportunities for future productivity growth that would otherwise be lost. ���A lack of support for manufacturing is sucking the dynamism out of our economy��� says Corbyn, giving the example of how cuts to subsidies to solar power have cut UK-based innovation in the sector. And he speaks of developing ���the virtuous cycle, where the success of one industry or company helps others.���

He���ll not thank me for saying this, but he���s echoing New Labour here with its enthusiasm for endogenous growth theory ��� the idea that success breeds success, that innovations and productivity gains today lead to more gains tomorrow.

In other words, he wants to sacrifice a bit of static efficiency to gain some dynamic efficiency.

The case for doing this isn���t purely economic. It���s plausible that the decline of manufacturing and rise of finance is one factor (of several) behind job polarization ��� the decline of half-decent jobs for diligent but unacademic people. This polarization, one could argue, has unpleasant social effects.

Insincere as many of his critics are, however, I fear they might have a point. Endogenous growth theory cuts both ways: if success breeds success, so failure breeds failure. The UK���s longstanding weaknesses in manufacturing ��� a lack of vocational skills, poor management and the consequent lack of animal spirits ��� might well condemn us to continued failure. And Corbyn ��� like most politicians ��� is I fear insufficiently heedful of a point made (pdf) by Landon-Lane and Robertson, that national policies might (within reason) be unable to do much to raise growth.

You might, however, draw another inference from such scepticism ��� that it shows that we need radical and broad-spectrum policies to try to raise growth: not just UK-biased government procurement but also better macro policy, a national investment bank, better training and so on.

I���ve an open mind on whether this can work. But Corbyn is at least asking the question, Which is more than can be said for the government. If Corbyn���s critics want to be more than tribalist gobshites, they would engage with it seriously.

July 23, 2018

The Brexit con

Brexiters told us that leaving the EU would be quick and easy and would save us ��350m a week. With a chaotic no-deal looking a real possibility, however, Jacob Rees Mogg now tells us it could take 50 years to reap the benefits.

What he���s doing here is something con-men have always had to do ��� stopping their victim going to the police when the goods they have charged him for fail to arrive. This job is called cooling the mark out, as described (pdf) back in 1952 by Erving Goffman*:

An attempt is made to define the situation for the mark in a way that makes it easy for him to accept the inevitable and quietly go home. The mark is given instruction in the philosophy of taking a loss.

Rees Mogg is employing the method Goffman called ���stalling.��� He���s saying that the goods will turn up, but just a bit later than promised and at a higher price.

The thing is, this tactic could work. It plays upon several psychological mechanisms.

One is a desire for consistency. As Robert Cialdini says:

Once we have made a choice or taken a stand, we will encounter personal and interpersonal pressures to behave consistently with that commitment. (Influence, p57)

One aspect of this is that people hate admitting even to themselves that they were wrong. They therefore look for reasons to believe their decision was a good one, and downplay evidence to the contrary. Stock market investors hold onto losing stocks in the hope they���ll break even: wishful thinking causes them to over-estimate future returns. The same wishful thinking might cause Leavers to think a chaotic Brexit will be worth it eventually.

Secondly, there���s the ���if it���s expensive it must be good��� syndrome. Peddlers of textbooks and financial advice play upon this by charging extortionate amounts. They do so because it works. As Dan Ariely famously showed, expensive placebos work better than cheap ones.

It���s for this reason that college societies often have humiliating initiation ceremonies. Having borne the cost of joining the society, you value its membership more highly (pdf).

Relatedly, there���s the ���ikea effect���. We tend to value things more highly if we have struggled for them; the home-assembled bookcase looks better than the factory-made one.

In this way, the very fact that Brexit is initially expensive might actually sustain support for it. People will think ���if it���s this much trouble, it must be worth having.���

Thirdly, there���s simple sunk costs: ���we���ve come so far and paid so much we can���t turn back now���.

And here���s the thing. A clever con-man can exploit these mechanisms and extort even more money from the mark. He can play the ancient Spanish prisoner (or advance-fee) con. The goods have been held up on route, he���ll say, and a small extra payment will release them.

In the Brexit context, this extra fee might well consist of labour market deregulation. To take advantage of the new trading opportunities outside the EU, they���ll say, we must be as competitive as possible.

It���s no coincidence that so many Brexiters such as Dominic Raab are also de-regulators.

Nor, perhaps, is it a coincidence that so many of them act just like con-men.

* Hat tip to Dan Davies��� superb Lying For Money.

July 22, 2018

Anti-communism as bad faith

One of the advantages of being old is that you get the sense of perspective that comes with having seen things before. So it is with the attacks on Ash Sarkar and Aaron Bastani for their support for communism.

I���m old enough to remember anti-communists in the 70s and 80s. Which means I remember just how much crass bad faith and hypocrisy they contained. Some of this bad faith was clear at the time, some is more evident with hindsight. Here are seven examples of what I mean:

- They attacked the Soviet Union for its denial of freedoms. But many of them opposed gay rights and ���women���s lib���, supported Pinochet and apartheid and to this day are relaxed about coercion within the workplace. The freedom many of them value is the freedom to oppress and dominate others.

- They criticized Marxism for having a crude conception of historical inevitability: Isaiah Berlin wrote a famous essay on the subject. But they claimed that the Gulags were an inevitable result of Marxism.

- They apply a double standard. Whereas they claim that oppression is an inseparable element of communism, they regard slavery and imperialism as mere accidental features of capitalism. I���m not sure this position is rescued by the fact that capitalism has thrived after the ending of imperialism and slavery. In many cases, imperialism was ended by armed struggle, not by enlightened capitalists realizing it wasn���t in their interests.

- When I was a young idealistic socialist I was told ��� again by people channelling Berlin ��� that it was impossible to achieve utopia because there are inescapable trade-offs between fundamental values such as equality and liberty. Some of those same people, however, are now blind to the trade-off Brexit reveals between sovereignty and prosperity: a meaningful free trade deal requires regulatory alignment, but this entails adopting some of other countries��� regulations, which is a loss of sovereignty.

- Again, when I was young, cynical old anti-communists told me that it was impossible to build a substantially better society because the crooked timber of humanity lacked the rationality and knowledge to do so. As Tim Worstall recently said, grand plans don���t work. Oddly, though, such scepticism about state capacity disappeared with Brexit: untangling 40 years of intertwined laws, we were told, would be simple.

- One example cold warriors gave of communism being the enemy of freedom was its attitude to migration: dissidents such as Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn were for years banned from leaving the USSR. These people are not so keen on free movement today, however. Many of those who cheered when Reagan said ���tear down this wall��� also cheered when Trump proposed building one.

- When they spoke of the Soviet Union, cold warriors claimed that centrally planned economies were a lousy idea. But centrally planned economies are still with us: bosses claim to be able to manage large complex organizations from the top down. Cold warriors are relaxed about this. They���re blind to the fact that if you want a modern example of a Stalinist you should look not among lefties but at men like Fred Goodwin or Philip Green. It���s not good enough to reply here that it someone doesn���t like their employer they can leave. None of us could escape the financial crisis, which was due at least in part to the failure of capitalist Stalinism.

Now, I do not say all this to defend Soviet Communism: it was an abomination. Nor do I decry those east European dissidents who paid a heavy price defending it. Western anti-communists, however, paid no such price. Quite the opposite. For them, anti-communism was and still is a very comfortable part of a defence of inequality in the west. In this sense, we can charge them with another double standard ��� a very partial reading of Adam Smith. Whilst they are keen to stress the virtues of the invisible hand, they are less keen to heed Smith���s warning that we tend to be too deferential to the rich and powerful:

We frequently see the respectful attentions of the world more strongly directed towards the rich and the great, than towards the wise and the virtuous. We see frequently the vices and follies of the powerful much less despised than the poverty and weakness of the innocent���The great mob of mankind are the admirers and worshippers, and, what may seem more extraordinary, most frequently the disinterested admirers and worshippers, of wealth and greatness. (Section 3 Ch III)

Subsequent work ��� on the status quo bias, just world illusion and system justification (pdf) ��� has vindicated Smith here. Not that you���d know it from defenders of capitalism.

Granted, Ash���s idea of communism needs a lot of work. But if I had to choose between her youthful idealism for a better world on the one hand, and smug defenders of an unjust and inefficient existing order on the other, I���ll choose Ash every time. As the woman who inspired my blog���s name sang, ���teenagers, kick our butts.���

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers