Chris Dillow's Blog, page 44

April 18, 2018

On thin predictions

Back in 2016 I wrote that ���immigration controls will hurt decent people���because they are the softest targets.��� Paul Cotterill interprets this as meaning that I saw the Windrush scandal coming. I think he���s being too kind, but this illustrates an under-appreciated point ��� that good predictions can be ���thin��� in the sense of containing little data.

I���ll give you two other examples from my day job.

One is that back in 2007 I pointed to record foreign buying of US shares as a warning that the All-share index would fall sharply over the following 12 months. Which it did.

Then last February I forecast that sterling would rise. Which it has ��� by 15% against the US$.

Now, I don���t say this to toot my own horn. (There's a reason why these examples are ten years apart!) I do so to point to something these calls have in common. Both are lacking in description. The forecast that share prices would fall in 2008 makes no reference to the financial crisis. And my forecast for sterling ignored most of the things that are usually thought (perhaps wrongly!) to determine exchange rates such as growth or interest rates.

Instead, both these calls rested upon single facts and single theories ��� that foreign buying of US equities was a measure of irrational exuberance (it still is) ; and that exchange rates overshoot (pdf).

These are not isolated examples. A single simple fact ��� is the yield curve inverted or not? ��� has done a better (pdf) job of predicting recessions than the more data-intensive forecasts of macroeconomists, most of whom have missed (pdf) almost all recessions.

What this tells us is that sometimes we don���t need big models to predict things ��� be they micro-founded or not. One strong fact sometimes beats lots of weak ones*. In these cases, we have lead indicators, but not any detailed explanation.

In saying this I am echoing Jon Elster:

Sometimes we can explain without being able to predict, and sometimes predict without being able to explain. True, in many cases one and the same theory will enable us to do both, but I believe that in the social sciences this is the exception rather than the rule. (Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences, p8)

You might think that this contradicts the message of Tetlock and Gardner���s Superforecasting. They say that foxes (who know many things) make better forecasters than hedgehogs, who know one thing.

I���m not sure there���s a contradiction here. For one thing, many of the cases they consider are one-off political events ��� sometimes quite obscure ones ��� where success requires careful data-gathering. In the cases I���m considering, however, data is abundant and the trick is to distinguish between signal and noise, to decide what to ignore. Occasionally, one fact sends a stronger signal than many. Which corroborates Tetlock and Gardner���s point, that ���in most cases, statistical algorithms beat subjective judgment.���

This is not, of course, to say that simple lead indicators always work. Obviously, they don���t. My point is merely that forecasting is not the same as modelling, nor the same as telling a good story.

* Certainly, rules of thumb often beat attempts to forecast particular events, but that's a different story.

April 17, 2018

The Windrush scandal: myths exposed

The appalling spectacle of Windrush generation immigrants being hounded and deported should help to dispel two great myths about politics.

Myth one is that racism is confined to the ���white working class���. Of course, some of these have backward attitudes which they express crudely. But equally, very many or more have lived happily with and alongside Windrushers. The harassment of them has been authorized by nice posh people who probably wouldn���t dream of using ���politically incorrect��� language.

Racism is not just about words. It���s about actions. In particular, it���s about the actions of those in power. As I complained months ago, we hear too much about the racism of the white working class and too little about that of the ruling class.

Only a few days ago the BBC and other right-wing media were hyperventilating about the (yes, disgraceful) anti-semitism of a few idiots. They were doing so whilst ignoring a more harmful form of racism being conducted by those in office.

Myth two is the myth of perfectibility ��� the idea that it���s possible to conduct a perfect policy with no ill-effects.

It is the case that most voters want immigration controls. As with Brexit, Theresa May interpreted this as meaning that they wanted a harsh and extreme version thereof. Hence her creation of a ���hostile environment��� for migrants: Ian Dunt and Stephen Bush are right to note that the deportations of Windrushers are the natural effect of this.

But this is not what voters wanted. They don���t want Windrushers expelled, just as they don���t want cuts in the numbers of foreign students. When voters want immigration controls, they are thinking of unskilled migrants and criminals, not French doctors, Chinese students or elderly Brits.

Maybe in theory it���s possible to distinguish between ���good��� and ���bad��� migrants. And maybe some governments somewhere do have the ability to do so. But the UK does not have that ability. As Amber Rudd said, the Home Office ���sometimes loses sight of the individual.��� (She���ll be livid when she finds out who���s running the department).

In practice, then, perfect immigration controls are impossible. This means we have to choose which mistake we make. Do we have a ���hostile environment��� which will hurt decent people? Or do we have a more liberal regime which will bring in some people voters would rather exclude? I���d prefer the latter. As I wrote months ago:

if you give power to the state it���ll be misused, because the actually-existing state is a stupid bully. Just as ���anti-terror��� laws have been used to harass journalists and peaceful protestors, so immigration controls will hurt decent people. And for the same reason - because they are the softest targets.

The case for liberty is, in large part, that the state is not to be trusted with extensive powers.

It���s tempting to conclude with some bromide hoping that lessons will be learned. This, though, is too optimistic. Politicians and the media rarely learn deep lessons from evidence.

April 13, 2018

Syria: the knowledge problem

There���s a danger that the question of whether we should intervene in Syria is becoming a left-right issue. Not only is this false, it���s a means of (deliberately?) ignoring the basic issue ��� one that is much more general than merely the conjunctural question of Syria.

It���s false because there are many rightists who have doubted the case for military intervention, such as John Baron, Julian Lewis and, I gather, Kate Andrews on Question Time last night. I don���t think this is wholly because they are little Englanders who care only about British interests. It���s because of their stance towards a key general question in politics: how much can governments know?

The case against bombing Syria is not that we should support Russia or Assad or that a ���political solution��� can be found. It���s that we do not know enough about the country to be confident that intervention will work. Yes, the situation is awful. But it���s quite possible that bombing will make it worse.

Faced with uncertainty, we must err on the side of doing nothing: if in doubt, do nowt. The Brainard principle should apply to all policy, not just monetary policy.

To put this another way, bombing Syria is an irreversible decision. We cannot unbomb the country if we decide that we were wrong to do so. If we don���t bomb, though, we can bomb later if we decide that the case for doing so has become strong. Bog-standard economics tells us that when we have uncertainty and irreversible investment opportunities, we should wait and see. (Dan Davies, has, as usual been good on this).

This is one lesson of the Chilcot report. He wrote (par 863):

Ground truth is vital. Over���optimistic assessments lead to bad decisions.

Can we really be confident we have sufficient ���ground truth���?

The contrary case to all this has been put by Johnny Mercer:

On issues of sensitive intelligence and national security, the PM sees the whole picture, and we should not constrain her

This, though, begs the question: does the PM really have the whole picture?

From this perspective, it���s no surprise at all that some rightists oppose military action. Free marketers such as Kate think the government doesn���t know enough about the economy to intervene successfully. By the same token, they might doubt whether governments can know enough to intervene militarily in other countries. This is a consistent scepticism about what policy-makers can know. Hayek���s famous essay on the limits of knowledge doesn���t just apply to economics.

Much of New Labour had the opposite view. I suspect that Blair���s decision to go to war in Iraq was the product of his overall ideology ��� an overconfidence about what top-down leaders could know.

In this sense, the Syria question should not be a left-vs-right one at all. Free market rightists and market socialists like me agree that centralized knowledge is often insufficient and so are intervention-sceptics. Those who are more optimistic about state capacity disagree*.

The debate we should have ��� not just in the Syria context but more generally ��� is: how much can we know? But because many politicians and columnists have built careers upon being overconfident, this is a question they don���t want asked. As Upton Sinclair said, ���It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it".

* You might object that this is not Corbyn's motive for opposing intervention. Maybe not. But doing the right thing for the wrong reasons isn't entirely to be deplored.

April 11, 2018

The Tyranny of Metrics: a review

Measurements can mislead us, especially when they are used as management targets. That���s the thesis of Jerry Muller���s The Tyranny of Metrics. He writes:

What can be measured is not always what is worth measuring; what gets measured may have no relationship to what we really want to know. The costs of measuring may be greater than the benefits. The things that get measured may draw effort away from the things we really care about. And measurement may provide us with distorted knowledge ��� knowledge that seems solid but is actually deceptive.

Muller provides lots of examples of this, mostly from the US. But you���ll all have examples of your own. In universities the Research Assessment Exercise (now the REF) contributed to increased administration costs and perhaps to the replicability crisis by incentivizing the publication of mediocre research. In schools, targets can encourage teaching to the test, endless revision and a focus upon the marginal student to the neglect of both the strongest and weakest. Waiting-time targets might distort clinical priorities. Immigration targets deter foreign students and lead to the harassment of people who have lived here for decades. Sales targets encourage workers to mis-sell financial products, cook the books, or increase risk by encouraging (pdf) ���liars��� loans. And so on.

All this will be familiar, especially to those of you acquainted with the work of John Seddon ��� although Muller puts it all concisely and well: Campbell���s law, which says that measures will be misused, was proposed way back in 1979. And it���s going to remain a big issue thanks to the rise of big data and machine learning ��� which, I suspect, will be the over-hyped discovery of weak correlations that don���t hold out-of-sample.

The Tyranny of Metrics is not, however, a diatribe against targets. Muller points to the experience of some US hospitals to show that metrics can work. They do so, he says, when they are ���based on collaboration and peer review���:

Measurements are more likely to be meaningful when they are developed from the bottom up, with input from teachers, nurses and the cop on the beat.

In other words, metrics can succeed when they are complements to knowledge: when they organize the tacit and dispersed professional judgements of people who know ground truth. Tim Harford makes a good point when he criticizes Muller for overlooking Paul Meehl���s finding (pdf) that simple statistics often out-perform professional judgment, but I don���t think Meehl was arguing that statistical models should be constructed and used in complete ignorance of professionals��� know-how. The latter informs the former, whilst the former in turn checks the latter.

Indeed, Muller���s evidence shows that metrics can fail when they are substitutes for knowledge ��� when top-down bosses try to supplant professional know-how.

This raises an under-appreciated point - that questions of what statistics tell us and whether target work are not merely technocratic ones. They are deeply political, because claims to power and wealth are founded upon claims of expertise. As Alasdair MacIntyre wrote:

Civil servants and managers alike justify themselves and their claims to authority, power and money by invoking their own competence as scientific managers���But is this true? Do we now possess that set of lawlike generalizations governing social behaviour of the possession of which Diderot and Condorcet dreamed? Are our bureaucratic rulers thereby justified or not? (After Virtue, p86-7).

The belief that people and organizations can be managed and controlled by simple measures imposed from above is one of the main foundations of bosses��� claim to power. In showing us that this belief is at least sometimes wrong, Muller has written a much more political book than many readers might think. And in doing so, he has also helped to advance the case for greater worker democracy.

April 10, 2018

Politics as risk management

There���s one point about politics which seems to me to be childishly obvious but which is under-appreciated, and which helps illuminate a number of policy issues.

It���s that we don���t live in a wholly knowable deterministic world in which setting policy is a matter of pulling the right levers with predictable effects. Instead, policy operates upon a distribution of uncertainties*. In some cases, the best policy is not so much one that achieves the best outcome but one which reduces the risk of bad outcomes ��� either the small risk of something really bad or the larger risk of moderately bad outcomes.

We should think of policy as risk management. Just as investors don���t try to maximize returns but also pay some heed to avoiding risk, so too should policy-makers.

As I say, this should be childishly obvious. But let���s apply it to some current issues.

- Anti-semitism in the Labour party. It seems this is mostly a matter of a few (though too many) idiots. This is low-level stuff: idiots spouting shit is normal in politics. Tolerating it, however, carries a big risk. Anti-semitic words might help to normalize anti-semitic behaviour: attacks and harassment of Jews. Low-level anti-semitism might therefore escalate. It���s reasonable then to demand that Labour have zero-tolerance of anti-semitism not so much because current levels of it are a big problem, but rather as a means of reducing the risk of something worse developing.

- Calls for military action in Syria. The problem here is that we know that military ventures carry huge risks. The rule ���don���t start wars��� might not be correct in every case. But it���s a good minimax rule of thumb. It���s a way of avoiding very heavy losses ��� of lives and money as well as political capital. Yes, interventionists are wholly right to say that inaction has consequences too. But it���s not clear to me that inaction is often as potentially catastrophic as action. This is especially the case because in foreign policy William Goldman���s maxim seems to apply: nobody knows anything. And Brainard���s principle ��� that policy should be cautious where there is uncertainty ��� should apply to all policy, not just monetary policy.

- Cuts to police numbers. Amber Rudd claims there���s no evidence these have led to rising violent crime in London. But if crime were wholly insensitive to police numbers, we could abolish the police entirely without crime rising. That seems absurd. There must therefore be some point at which fewer police leads to more crime. And we have at least one piece of evidence here that we might be around that point. Stephen Machin and colleagues show that when police were redeployed from outer London to central London after the 7/7 terrorist attacks ���crime fell significantly in central London relative to outer London.��� That suggests police numbers do matter. Granted, we cannot prove that people have been killed as a result of police cuts. But it is surely plausible that the cuts have increased the risks some people face of suffering crime.

- Fiscal policy. Again, this is a matter of risk management. As Simon has said, the problem with austerity is that it is risky. It increases our reliance upon uncertain monetary policy ��� policies which our low rate of growth show to have been inadequate. On the other hand, its advocates claim that austerity reduced the risk of a bond market crisis and rising borrowing costs. Personally, I think that risk was small and manageable by QE. But the point is that the debate is about risk management.

I could of course go on: one case against Brexit, for example, is that it increases uncertainties for (to me) no offsetting benefit. Conversely, the virtue of many policies aimed at increasing productivity ��� better education, stronger competition policy, better financing of start-ups and so on ��� is not so much that they will definitely work but that they are free hits: even if they don���t raise productivity they���ll do little harm and perhaps some good.

Although the general principle here should be obvious to all adults (though you may well disagree with my applications of it) I fear it is under-appreciated in the media. Columnists are more often than not overconfident gobshites who fail to grasp the extent of uncertainty and boundedness of their knowledge: how often do they attach confidence intervals to their claims?

And imagine ��� if you can - the improbable event of a politician appearing on (say) the Today programme and saying ���We cannot know the precise effects of this policy, but we hope it will at least avoid serious harm.��� John Humphrys would give her a horrible time. Our dumbed-down media, with its demand for certainty where none is possible, mitigates against sensible politics. ���We don���t know��� is a phrase that should be used more often.

* I mean uncertainties in the Knightian sense: often, we cannot quantify probabilities or know their precise distribution.

April 9, 2018

On socialized preferences

I recently wrote approvingly of SImone de Beauvoir���s claim that ���one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman���. ���Feminine��� preferences such as a lack of pushiness and tendency not to study maths and science might, I said, be socialized ones rather than innate. This prompted some to ask how much evidence we have that preferences are shaped by social pressures.

Quite a bit. Some more evidence in support of de Beavoir���s theory has come from recent research in China. Alison Booth and colleagues say:

Women in Beijing who grew up during the communist regime, when gender equality was emphasised, are more competitively inclined than their female counterparts who grew up during the post-1978 reform era. These women are also more competitively inclined than their counterparts in Taipei.

In the same vein Uri Gneezy and colleagues show that women are no less competitive than men in matrilineal societies (pdf). Also, their willingness to compete can be increased by the presence of role models, and by raising the salience of career concerns relative to their gender.

All this is evidence that ���acting girly��� is at least to some extent a social rather than genetic construct.

In truth, though, this is only the tip of the iceberg of evidence that preferences are the product of social influences rather than exogenous data.

We have (at least) four other bodies of evidence.

One is that people tend to adapt to their situation. We might look forward to getting married, or dread widowhood, but within a few years of both events we are as happy as we were before them. This suggests that what we want rises or falls with circumstances. As G. K. Chesterton said: ���No man demands what he desires; each man demands what he fancies he can get."

An important sense in which this is the case is that people adapt even to abject poverty. Amartya Sen has written:

Deprived people tend to come to terms with their deprivation because of the sheer necessity of survival, and they may, as a result, lack the courage to demand any radical change, and may even adjust their desires and expectations to what they unambitiously see as feasible (Development as Freedom, p62-63)

It's also the case that people adapt to inequality: the higher is inequality the greater is our preference for inequality. Today, for example, centrist supporters of the status quo believe it fair that the richest 1% get over 10% of income. In the 1980s, support for the status quo entailed believing the 1% should have had only around 7%.

Our second body of evidence is that preferences are shaped by our formative years. Ulrike Malmendier has shown that people who experienced recessions when they were impressionable prefer to hold fewer (pdf) equities even years later than those who experienced booms. Similarly, CEOs who grew up in recession prefer (pdf) their companies to have lower debt and more cash than CEOs who enjoyed better conditions.

Thirdly, there���s the obvious fact that economic preferences such as willingness to trust others (pdf) or to pay tax (pdf) differ from country to country. This might be because even quite distant history shapes today���s preferences: a country���s history of oppression by an imperialist power might leave people willing to dodge tax even centuries later, for example. And it���s also because culture matters. As David Hirshleifer and Siew Hong Teoh say in a new paper:

Economic attitudes are culturally transmitted, and folk economic ideas are often linked together as ideologies, such as socialism or free market ideologies. This means we need to understand how culture evolves, and an explicit focus on the cultural, not just the genetic, evolutionary process to understand the evolution of economic issues.

Our fourth body of evidence is simply that our preferences are shaped by peer pressure. How much we spend, how we invest, how hard we work and what (pdf) and how assiduously we study are all influenced by those around us.

Now, this evidence does not mean that preferences are wholly socially influenced and that (say) genes are irrelevant. It does, however, have some important implications.

One is that economists��� assumption that preferences are just given is wrong to at least some degree. Of course, it���s reasonable for some analytical purposes to taken them as given. But a useful working assumption must not be mistaken for reality.

There is, though, a much more radical implication. If preferences are shaped by social forces rather than by a wholly rational assessment of our interests then satisfying preferences might not have much if any ethical value. Amartya Sen has written (pdf):

Consider a very deprived person who is poor, exploited, overworked, and ill, but who has been made satisfied with his lot by social conditioning (through, say, religion, or political propaganda, or cultural pressure). Can we possibly believe that he is doing well just because he is happy and satisfied? Can the living standard of a person be high if the life that he or she leads is full of deprivation? The standard of life cannot be so detached from the nature of the life the person leads. As an object of value, happiness or pleasure (even with a broad coverage) cannot possibly make a serious claim to exclusive relevance.

If we merely satisfy preferences, we���ll not give anything to such a deprived person. After all, she (the right pronoun mostly) doesn���t want anything. To this extent, satisfying preferences can perpetuate and even increase injustice: we give too little to the satisfied poor and too much to the over-entitled rich.

Partly for this reason, Daniel Hausman (among others) has argued that we have no ethical reason to satisfy preferences when these are a bad guide to people���s interests. Which, of course, calls into question the value of (actually existing?) democracy.

April 5, 2018

Thoughts on the gender pay gap

What do gender pay gaps tell us? Here are some of my thoughts.

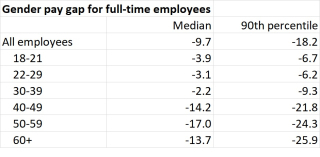

My table shows the data, taken from the latest ASHE survey. This shows that the median woman working full-time earns 9.7% less than the median full-time male employee. This is the same as the median pay gap reported recently by large firms.

However, the pay gap is much smaller for younger workers than older ones. This might be because there���s a pay penalty for being a mum. If you take time off or go part-time after the birth of a child you lose pay progression which you never recoup. The fact that lesbians earn significantly more (pdf) than straight women is consistent with this.

Another explanation, though, is that older women suffered sexism in the 70s and 80s, which retarded their pay throughout their lives.

I think Kate Andrews has a point when she says this gap could be closed if firms simply hired more men into low-paid jobs and denied jobs to less skilled women. That, though, isn���t just a point about the pay gap but a point about the tyranny of metrics generally: any simple measure can be gamed. The point about simple measures of the pay gap isn���t that they should be closed anyhow but rather, as Ben says, that they should help raise questions.

The median gender pay gap, though, is not all the story. The pay gap for higher-paid women is much bigger. A woman earning more than 90% of other women earns 18.2% less than a man who earns more than 90% of men.

This gap in part reflects high inequality among men. If well-paid men earned less, the pay gap between male and female high earners would shrink.

I suspect there���s a reason for this big gap. In top jobs pay is set not so much by a thick market as by bargaining over a joint surplus. And women are in many (pdf) circumstances less good at bargaining (pdf) than men. As Claer Barrett advises, women should be pushier.

Julian Jessop has a point when he says these gaps might not reflect overt discrimination by employees. They might instead be due to women sorting into lower-wage jobs. Airlines, for example, have big gender pay gaps because women tend to be low-paid cabin crew whilst men are higher-paid pilots.

Such gender-based preferences, however, are NOT the end of the story. For one thing, as Sarah O���Connor says, employers might perhaps do more to accommodate such preferences for example by not penalizing women who want to work part-time so much.

But there���s another point here that is grossly under-appreciated. It���s that preferences are not natural and given. As Simone de Beauvoir said, ���one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.��� Women���s relative lack of pushiness or ambition, or their preference for less well-paid work, might be due instead to the way they are socialized.

To cite just two examples from conventional social science, Alison Booth has shown that girls from single-sex schools are as competitive as boys. This, she says, ���suggests that observed gender differences might reflect social learning rather than inherent gender traits.��� And Marta Favara has shown that girls who go to single-sex schools are more likely to study maths and sciences than others. In both cases, all-girl schools (at the margin) discourage girls from acting girly and so steer them away from stereotyping.

In this sense, two things might both be true. It might be that the gender pay gap is not due to employers discriminating against women. But nevertheless it might also be true that women are the victims of sexism because of (among other things) how they are socialized.

There���s an analogy here with another issue: Oxbridge���s lack of admissions of poor students. Maybe there is little outright discrimination against them. But many poor students nevertheless suffer inequality because of wider social forces: poor schooling and mentoring, a learned lack of ambition and so on.

The point here is a simple one. Inequalities are not necessarily due to bad people deliberately doing bad things. They can instead be the result of impersonal mechanisms.

April 3, 2018

Inequality and poverty

Headteachers say that children are going to school malnourished. How can we reconcile this with the fact that official figures show that inequality has been, in Chris Giles��� words, ���remarkably stable��� since the early 90s?

Very simply. The evidence that inequality has been stable comes from the fact that the Gini coefficient hasn���t changed much. However, the Gini is a measure of the average of income inequalities. And of course, an average can be unchanged if some components rise whilst others fall. Which is just what���s happened.

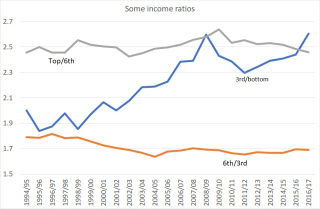

My chart gives a gist of what I mean. It shows some income ratios, based on real incomes after housing costs taken from the latest HBAI data.

What this shows is that we���ve seen a big increase in one inequality since the late 90s ��� that between the third decile and the bottom decile.

In fact, the bottom decile has done really badly. Its real incomes after housing costs haven���t grown at all since 2000 whilst median incomes have risen over 27%. And since 2011-12, the bottom decile���s real incomes have fallen 6.3%. This is consistent with reports of an increased intensity in poverty such as increased use of foodbanks and child malnourishment.

Those around the third decile, however, have seen their incomes rise ��� in part because they have benefited from a rising minimum wage. Their incomes have risen relative to those just above median incomes ��� those in the 6th to 8th deciles, thus reducing some inequalities. This is in part because of job polarization ��� the loss of job opportunities for those in once-decent to middling jobs such as secretaries and tradesmen.

And since 2010, we���ve also seen a narrowing of inequality between the top decile and middling incomes. (These data, however, tell us nothing about really top incomes which are hard to measure but which probably also fell since the crisis).

What we���ve seen, then, is an increase in one form of inequality: the very poorest have fallen behind everybody else. But this has been offset by falls in other inequalities, such as that between high incomes and those on slightly-below median incomes. A stable Gini coefficient is therefore consistent with an increased intensity of poverty and for that matter with very different types of society.

In this context, I disagree with those centrists and rightists who point to a flat Gini coefficient as if this sufficed to show that the left is wrong to worry about inequality. For one thing, flat overall inequality is consistent with increased poverty. For another, even if the Gini coefficient has levelled off (possibly (pdf) only temporarily) it might have done so at too high a level; we must avoid a form of anchoring effect whereby our perceptions of what���s fair are overly coloured by actual inequality. And thirdly, just because inequality has stopped rising does not mean that the damage done by its earlier rise will go away. If a man has been hit by a bus you not restore him to health merely by stopping the bus. And of course, income inequality is only one of many inequalities: inequalities of power are also important (maybe more so).

We should ask: what sort of economy and society we want? A single statistic such as the Gini coefficient is not much help in answering this.

March 31, 2018

Power without conspiracies

On Twitter this morning Sam Freedman asked ���whether it's possible to see politics as entirely about power structures without eventually thinking conspiratorially?��� I think it is. There are (at least) three elements here.

The first is that capitalism is an emergent process: nobody designed it from scratch. It emerged as the unintended outcome of millions of decisions, and it is not simply individual behaviour writ large. As Marx said, ���men make their own history but they do not make it just as they wish.���

One aspect of his concept of alienation is that all of us ��� even capitalists ��� become subject to impersonal forces beyond individual control. For example, he thought that poor working conditions were due not to ���evil��� capitalists but to the fact that competition forced even benign capitalists to hold wages down*:

Free competition brings out the inherent laws of capitalist production, in the shape of external coercive laws having power over every individual capitalist. (Capital Vol I Ch 10, part 5)

A similar process might explain the rising pay of the 1%. If each individual board of directors wants to attract a top-quality CEO, they���ll feel the need to drive up pay. The upshot will be an arms race in which shareholders collectively pay more than they need to whilst being unable to coordinate to cut CEO pay.

The relative lack of coops might also be due to emergent processes. Credit constraints and problems of collective action ��� it���s difficult to get dozens of people to agree to anything ��� might stymie their spread. Capitalistic modes of production thus dominate without them being more efficient but without any conspiracy.

A second process is ideology. People don���t support the existing order merely because they���ve been indoctrinated by the Tory press. There are spontaneous processes whereby this happens.

One, demonstrated by Kris-Stella Trump, is a form of anchoring effect; our idea of what���s fair is shaped by the actual distribution of income. For example, if someone were to say that the appropriate share of income going to the top 1% should be 7% we���d regard them as very left-wing: the share today is almost 14%. In the mid-80s, however, such a view would have been merely a defence of the existing distribution.

A second process is system justification (pdf). This can arise from wishful thinking: people want to believe the world is fair and the wish is father to the belief.

A third is adaptive preferences. As Amartya Sen has said:

Deprived people tend to come to terms with their deprivation because of the sheer necessity of survival, and they may, as a result, lack the courage to demand any radical change, and may even adjust their desires and expectations to what they unambitiously see as feasible. (Development as Freedom, p63)

Just as lonely men become accustomed to bachelorhood, and even like it, so the poor and powerless do to their circumstances. There���s no conspiracy here, just the powerful tendency of humans to adapt.

Thirdly, there���s the relationship between capitalism and the state. Imagine a benign government which wanted high wages and employment. It might adopt pro-capitalist policies to achieve these simply because capitalists have power over investment and hiring decisions. The desire to maintain business confidence and stop firms relocating overseas might cause it to maintain low taxes on profits and top incomes, ensure a quiescent labour force, and have little regulation. It might even ��� in a world in which real interest rates are high ��� justify fiscal austerity to hold down borrowing costs. Depending upon conjunctural features of capitalism such policies might or might not be justified: they were more so in the 90s than they are now. Whether they are or not justified, however, is a matter of judgment. We don���t need to invoke conspiracies.

None of this is anything like a complete description of the mechanisms at work. I hope, though, that they are sufficient to show that we can think of capitalism in terms of power relations without invoking conspiracy theories.

* Marx might well have been too pessimistic here. Competition can bid up wages too ��� if firms want to pay above the going rate to reduce staff turnover or induce more effort. And some firms might have more discretion over wages than Marx thought.

March 30, 2018

Irrelevant IQ research

There���s been an unedifying row between Ezra Klein and Sam Harris about race, IQ and genes. I���m not sure this gets to the nub of the matter.

To see my point, let���s assume that the most provocative claims made by Charles Murray in The Bell Curve are correct. As summarized by Harris these are: that ���general intelligence��� is a scientifically valid concept and can be measured by IQ tests; that IQ is highly predictive of success in life; that mean IQ differs across populations; and that IQ is partly genetically determined.

Many of you will find this assumption heroic. IQ has a big environmental factor: it can be increased by schooling, better diet and by less pollution, poverty or oppression. The extent of heritability is questionable. The link between IQ and income is dubious, and that between IQ and wealth even so. And as Charles Manski has pointed out, even if heritability of IQ is large, and IQ is an important cause of poverty, it does not follow (pdf) at all that anti-poverty policies are ineffective.

For the sake of my argument, though, let���s put aside these doubts. Even then, the race-IQ-genes agenda tells us little. I mean this in four ways.

First, a correlation between IQ and success in life tells us nothing whatsoever about the justice or not of an economic system.

I suspect there was such a correlation in medieval China thanks to its civil service exams, or in the Soviet Union: it probably took a lot of cognitive skill to rise up the byzantine bureaucracy. Few, though, would consider those to have been just societies.

In fact, it might well be the case that in a just society the IQ-success correlation is lower than it is in unjust ones. Dictators want underlings to have sufficient cognitive ability to take and implement orders - IQ need not mean having a rebellious mind ��� which will generate an IQ-success correlation. In free societies, however, we reward people according to many criteria of which IQ is only one. Joey Essex, Paris Hilton and the Kardashians probably do better in capitalism than they would under communism, but they drag down the IQ-success correlation.

Whether capitalism is just or not not is, then, a question wholly separate from any link it generates between IQ and success.

Secondly, there are countless natural genetic differences between people which do not yield large systemic inequalities: eye colour, hair colour, footedness, and so on. None of these are thought to betoken differences in moral worth, so why should IQ be different?

And there are other genetic differences which produce moderate economic inequalities but not ideologies that defend them. Tall men earn more than short ones, but (moderately) short men haven���t endured centuries of oppression, stigma and belief in their ���natural��� inferiority as women and blacks have. Why are race and gender differences different from other genetic differences? The answers lie in history and social science, not in genetic science.

Thirdly, even if we concede that blacks have a lower average inherited IQ than whites, this explains only a fraction of the inequality they experience. Would Stephon Clark have been able to dodge the 20 bullets the police fired into him if only he���d had a higher IQ?

In both the UK and US, black men earn less than whites even if we control for observed ability. Economists at the San Francisco Fed wrote recently:

A significant portion of the wage gap between blacks and whites is not traceable to differences in easily measured characteristics, but rather is unexplained within our model���Perhaps more troubling is the fact that the growth in this unexplained portion accounts for almost all of the growth in the gaps over time.

Put it this way. Imagine two men of identical intelligence. One is born into a poor black family, the other into a wealthy white one. Which has the better chances in life? Differences in outcome depend upon opportunities as well as (and perhaps more than) than ability. As Arsene Wenger said:

Can you name one Formula One driver from an African country, apart from South Africa? And can you really imagine that there is not one guy in Africa with the talent to be a Formula One driver? Why are they not there? Because no one has given them a chance.

What���s true across countries is also true within them.

There���s something else. Insofar as inequalities between people are due to inherited genes, one big philosophical theory says this justifies their elimination. Luck egalitarianism says that inequalities that are due to luck should be neutralized. On this view, a good genetic inheritance ��� being a matter of luck beyond one���s control - entitles you to no more than anybody else. In fact if we combine this view with Murray���s hypotheses, there���s a case for redistributing income towards blacks.

Few of Murray���s supporters, however, favour this. From one perspective this is odd. The question of the validity of luck egalitarianism is logically independent of the truth or not of Murray���s claims. On logic alone, therefore, we'd expect to see some luck egalitarian Murrayists arguing for income redistribution towards blacks.

So why don���t we? Nathan Robinson suggests one reason. The function of Murray���s research, he says, is to exonerate whites for the suffering of blacks, because it blames this upon nature not society.

But of course, this is false. I���m not sure this is a case for closing down research into genetic differences between races. It���s just that we shouldn���t pretend that such research tells us anything about what to do about inequality. It doesn���t.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers