Chris Dillow's Blog, page 46

March 6, 2018

Getting away with murder

Simon reminds us of the massive costs of fiscal austerity: not just a loss of around ��10,000 per household, but tens of thousands of deaths, despair for millions of victims of a harsh benefits system, and the economic cost and social divisions caused by Brexit which would almost certainly not have happened were it not for austerity.

Austerity, then, must be one of the most catastrophic policies in peacetime British history. Which poses the question. How have the Tories ��� not just Cameron and Osborne but their Cabinet colleagues who are still in government ��� escaped the censure they deserve? Why are they not universally regarded with abject contempt?

There are, I suspect, many possible reasons. Here are a few.

One is plain deference. We have, wrote Adam Smith, "a disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful":

We frequently see the respectful attentions of the world more strongly directed towards the rich and the great, than towards the wise and the virtuous. We see frequently the vices and follies of the powerful much less despised than the poverty and weakness of the innocent.

If you went to the right schools, are in the corridors of power, and give the impression of entitlement and confidence you���ll get a free pass. There's a reason why the word "confidence" is in the phrase "confidence trickster."

Secondly, there���s been a handy scapegoat. As Simon says, blame for stagnant real wages and pressures on public services have been shifted from the Tories and Lib Dems onto immigrants.

Thirdly, there���s adaptation and a ���devil you know��� effect. The costs of austerity crept up on us gradually rather than as a sudden shock, so voters became accustomed to them. And we never see the road not taken. There���s no Jim Bowen telling us ���here���s what you could have won.��� The costs of austerity are underweighted because there���s no clear contrast in the public mind between actual policy and the feasible alternatives.

Fourthly, there are many political commentators ��� not just on the right ��� who don���t think of politics as a matter of real lives and genuine hardship but as a cosy parlour game in which what matters is who���s up and down, and who can present a ���credible��� image. To them, talk of ���sound finance��� matters more than human suffering, just as ���sovereignty��� trumps hard cash.

This is magnified by a perhaps unavoidable bias in even the so-called impartial media. What I mean is that the news is ���flat���. A policy that costs 10% of GDP doesn���t get 100 times the coverage of one that costs 0.1% of GDP. A ���car crash interview���, a ���gaffe��� or a minor ministerial resignation are all treated much the same as a genuinely disastrous policy. The BBC is lousy at distinguishing what matters from what doesn���t.

And then there���s class. There is always class. The cost of austerity is, as Simon says, ���concentrated on those at the bottom end of the income distribution.��� Those at the top end, by contrast, have done OK. Osborne���s ���fiscal conservatism and monetary activism��� helped to raise share prices and house prices to the benefit of the rich.

And it���s these that shape the public discourse. They have vastly more voice than the poor, and not just because they own the press. Just listen ��� if you can bear to ��� to any BBC politics programme: Question Time, Today, Sunday Politics, whatever, and ask yourself: what is the average income of the speakers? It is, quite likely, ten times that of a minimum wage worker. People on six-figure salaries account for less than three per cent of the workforce but, I suspect, well over half of the political voices we hear on the BBC. The interests and concerns of the Bubble are thus grossly over-weighted relative to those of the victims of austerity.

I don���t pretend this is a complete list of the reasons why the Tories have escaped so lightly. But the fact is that they have done so. They have, almost literally, gotten away with murder.

March 4, 2018

On Tory dilettantism

"The Republicans are the party that says government doesn't work and then they get elected and prove it." Nick Cohens's piece on the "bullshit right" and "its dilettantish, know-nothing contempt for detail" reminds me of that line from P.J. O'Rourke.

This highlights a longstanding divide about attitudes to politics between the right on the one side and centrists and leftists on the other.

What I mean is that left and centrists have, mostly, had a rationalist attitude to politics. They theorize, problematize, philosophize and seek technocratic solutions to political issues. In this sense, people as different as (say) Andrew Adonis and Paul Mason have something in common.

By contrast, there is a tradition on the right of rejecting this. Michael Oakeshott perhaps expressed this best. In his essay "Rationalism in politics" he contrasted the rationalist approach to politics as a technocratic solving of problems to a conception of politics as embodying a tacit "practical knowledge" which relied upon habit and the accumulated wisdom of ages.

This latter view is dilettantish, in the sense that it is sceptical about the feasibility of expertise. For years it defended know-nothings' pursuit of power as a means of stopping rationalists taking over: for much of the mid-20th century, conservatives saw their function as simply to govern rather than to have a plan. Having a "contempt for detail" fits this tradition of opposing rationalist plans generally.

And here's the thing. There's something to be said for such dilettantism. Let me give just two examples from monetary policy.

One was the UK's membership of the ERM. This was debated rationally for years before the UK formally joined the system in 1990. But the policy was a lousy idea that ended in ignominy. By contrast, inflation targeting was adopted in a panic with little prior public or academic debate and yet has proven more successful.

A second example is QE. Ben Bernanke famously quipped that "the problem with QE is it works in practice, but it doesn���t work in theory.��� That might not be precisely right. But it captures an important point - that QE was the product of practical judgement rather than rationalist theory. As Richard Bookstaber points out in The End of Theory, formal models collapse in crises and what we need is experience and judgment (drawn from science and literature as well as economics) rather than rationalist models. As Mike Tyson put is: "everyone has a plan til they are punched in the mouth."

There is, therefore, something to be said for relying upon judgment and muddling through rather than upon rationalism.

This, though, is not at all to defend Tories. The problem is that they have not been consistent Oakeshottians. Quite the opposite. As Jerry Muller reminds us in The Tyranny of Metrics, it was Thatcher who introduced new public management into government, which is an attempt to supplant the practical judgment of professions with the rationalist scientism of bosses. And Brexit itself is in a sense profoundly anti-Oakeshottian. It is motivated by a historical myth of Britain as a nation standing alone and a rejection of attempts to muddle through with imperfect actually-existing institutions.

Conservatives, then, are not consistently and coherently dilettantish. Instead, they are merely a party seeking to promote the power of a few (in the case of managerialism) and prejudice. It's as if they actually want to prove Corey Robin right.

March 2, 2018

Limits of laws

In what contexts are there limits to what can be done by laws and contracts?

It���s clear that there are such limits. As Oliver Hart and Ronald Coase (pdf) pointed out, it can be prohibitively expensive or perhaps even impossible to write contracts specifying what each party should do in every contingency. In such cases, it makes sense for firms to do jobs in-house rather than contract them out and enter the ���Coasian hells��� described by Alex.

A similar thing applies to laws in general. These can be badly written or too difficult or expensive to enforce.

Two different things I���ve seen recently pose this question.

One is the university lecturers��� strike. It seems to me that universities are a domain in which Akerlof���s gift exchange model of labour markets must operate. Lecturers and researchers work outside of their contracted hours ��� not least because creativity doesn���t switch on at 9 o���clock and off at five. They therefore supply goodwill. But this requires reciprocation in the form of employers respecting pension rights and not being heavy-handed. Lecturers must transmit to their students not just knowledge but an enthusiasm for their subject. They cannot do this if everybody is sticking to the letter of contracts and if they feel oppressed and ripped-off. Mutual understanding creates a better environment.

My second example is Brexit. Remainers point out that Brexiters��� demands are ���logically impossible to deliver.��� This is true if we think in purely legalistic terms. But it might not be if we think more loosely. I suspect* that Brexiters think that whilst legal formalism might require a hard border between Northern Ireland and the south they need not in practice actually police it. And if this leads to a bit of smuggling, that���s a price worth paying to keep everybody happy. De jure and de facto can diverge.

David Allen Green has said:

The EU produces papers and drafts. The UK produces newspaper articles and speeches. The EU is using process, the UK is using publicity. This is why the EU has the advantage in the Brexit negotiations.

He���s right, there is a culture clash here. The EU looks to law and formal agreements, whilst Brexiters speak of ���statements of intent��� and of working things out which their interlocutors find irritatingly vague.

But what if the vagueness is a feature not a bug? What if ��� pace Polanyi ��� some things cannot be expressed formally? Maybe solutions lie in there being a divergence between the law and the truth on the ground.

Now, I offer these only as tentative suggestions. I might be wrong about either or both.

But there���s an oddity here. Many of you, I suspect, agree with me in the first case but disagree in the second and vice versa. And it���s possible that some of you are right. But the issues in both cases are surprisingly similar; both pose questions about the merits of laws and contracts relative to informal understandings.

* Based on that under-appreciated research method, conversations in pubs.

February 28, 2018

Free speech after Mill

We need to reconsider the case for free speech, because the classical liberal case for it is questionable.

Robert Sharp recently echoed John Stuart Mill when he said:

Our own opinions, beliefs and values should always be tested, less they become yet another kind of dogma...With each iteration, we refine our arguments and can persuade new people to our point of view.

This is true in many cases: it���s why we should tolerate, and even welcome, Economists for Free Trade. But in the case Robert discusses ��� Richard Littlejohn���s homophobia ��� it���s not so clear. The benefits to us from decent people like Robert having a more refined opinion of the errors of homophobia are quite possibly outweighed by the threat that gay people feel from seeing homophobia normalized in the mass media.

There���s something else. Mill thought that free speech would lead to intellectual progress:

[Mankind���s] errors are corrigible. He is capable of rectifying his mistakes by discussion and experience. Not by experience alone. There must be discussion, to show how experience is to be interpreted. Wrong opinions and practices gradually yield to fact and argument: but facts and arguments, to produce any effect on the mind, must be brought before it.

This, though, is deeply doubtful. Facts are dismissed as ���fake news��� and evidence is interpreted with asymmetric Bayesianism; we are credulous about evidence that supports our prior views but sceptical of that which disconfirms it. Fact and argument lead not to the rectification of error but to stronger polarization. As Lord, Ross and Lepper concluded (pdf) back in 1979:

Social scientists can not expect rationality, enlightenment, and consensus about policy to emerge from their attempts to furnish "objective" data about burning social issues.

Our supposedly impartial media is no help here. It consistently failed to call out lies during the EU referendum, and it continues to give insufficiently critical coverage the peddlers of those falsehoods. The Brexit debate has been top of the news agenda for two years and yet no intelligent person on either side considers it well-informed. Oliver Norgrove, a Brexiter, surely speaks for many on both sides when he decries ���elected officials barely able to understand the basics���, ���intellectual vacuums��� in both main parties and ���ignorant headline-grabbers���.

The ���impartial��� media does, however does something effectively. Cathy Newman���s now-notorious uncomprehending interview with Jordan Peterson showed that it is incapable of coping with voices that don���t conform to a narrow range of views. As Ryan Bourne says:

Certain viewpoints from certain spokespeople are just not heard on the media.

He���s speaking from a rightist viewpoint, but I suspect his point generalizes. Many valuable perspectives ��� Oakeshottian conservatives, left libertarians, free market egalitarians and so on ��� are largely excluded from public discourse. One reason why Corbyn got such bad coverage especially early in his leadership was, I suspect, not so much that the BBC was actively hostile to him, but that it was so in thrall to a narrow Westminster-centric conception of politics that it just could not comprehend something different.

I say this with regret, but I fear Mill is no longer relevant to the debate about free speech. He was writing in an age before the mass media, when discussion was to a large extent among equals ��� albeit posh white men. He could not have anticipated the truth of Afua Hirsch���s point:

The marketplace of ideas, like many other markets, has monopolies, rackets and biases. Long-established ���suppliers��� of opinions with entrenched positions in ���the sector��� enjoy huge advantages.

���Free speech��� has become one more means through which the mega-rich exercise power to, as Simon says, seriously distort democracy.

Now, I���m not sure this is a case for repressing speech: laws will be used against the powerless rather than the powerful. Instead, what I���m saying is that we need to move beyond romantic twaddle about actually-existing free speech being a road to truth. Instead we need to ask: what would a rational, pluralistic inclusive Habermasian political discourse look like?

I agree with Paul that we need

a public sphere in which, as far as possible, all citizens have a right to express, and have heard their views, through formal democratic structures and civil society mechanisms.

This of course requires radical changes. But what sort? To what extent are they compatible with currently-existing capitalism?

Underneath those questions, however, I have a nasty one. What if the many irrationalities that distort debate now are due not just to capitalist ideology and power structures, but to innate flaws in human reasoning? What then?

February 27, 2018

Labour: the party of business?

Is Labour now the party of business? This is the question posed by the fact that the CBI has endorsed Jeremy Corbyn���s support for the UK to be part of a customs union with the EU.

I know, I know. The question seems absurd given Labour���s calls for nationalization of utilities and higher corporate taxes*. From two other perspectives, however, the question is sensible.

First, let���s assume that businesses��� interest is in having a high profit rate.

This rate, by identity, is equal to the share of profits in output, multiplied by the output-capital ratio.

Many of Labour���s policies might be bad for the share of profits ��� such as higher minimum wages, greater regulation of exploitative practices and stronger workers��� rights.

But they might well be good for the output-capital ratio. A looser fiscal policy would have this effect, insofar as it is not offset by tighter monetary policy.

And several Labour policies might well expand profit opportunities. Infrastructure investment would have this effect, as would a Mazzucato-style ���entrepreneurial state��� ��� one which helps the private sector with research and development. And Labour���s National Investment Bank is (pdf):

a response to the failure of the UK banking sector to provide longer- term loan funding for enterprises, for small and medium-sized enterprises especially, or to support innovation in forms of productive organisations.

It is perhaps insufficiently appreciated that many smaller businessmen (and ex-businessmen!) despise bankers, and would welcome anything that reduces their dependence upon them.

There is, though, a second perspective here. In the long-term, business needs not just profits but also legitimacy. And a system in which real wages for the many stagnate and in which young people have no hope of owning property, whilst a handful of people make millions and dodge taxes is one that lacks legitimacy. In removing egregious injustices, Labour promises to save capitalism from the capitalists, to use Rajan and Zingales��� words (pdf), by shoring up support for a reformed system.

This poses the question: what is business? The grasping (and inefficient) plutocrat is only part of the story. There are 2.8 million businesses in the UK. For every Philip Green or Fred Goodwin there are thousands of decent people struggling to make a payroll in the face of unreliable bankers, road congestion and an idiot Brexit policy. Labour can speak to these. Ed Miliband���s distinction between producers and predators was a good one.

You might think all this is hard to square with claims that Corbyn and McDonnell are Marxists. I���m not so sure they are. They are instead radcial(ish) social democrats whose priority is to improve living conditions for workers. They are Marxists insofar as they perceive ��� rightly ��� that capitalism is failing to do this. But they are willing to give a reformed capitalism a chance to deliver the goods again. There are many types of capitalism besides kleptomaniac neoliberalism ��� even though much of our imbecile press cannot see this.

You might also question how many votes there are in appealing to business. There are none at all if this means cosying up to elites. But this is the opposite of what Labour is doing. It is, instead, showing an awareness of the real needs of real people. And that is much more than a Brexit-addled Tory party is doing.

* If you believe the incidence of corporate taxes falls upon workers or consumers ��� in the form if higher prices or lower wages ��� then they are not anti-business, except insofar as they are bad for the general economy.

February 23, 2018

Enlightenment & the capitalist crisis

In his latest book, Enlightenment Now, Steven Pinker claims that the Enlightenment has worked, and that ���health, prosperity, safety, peace, knowledge, and happiness are on the rise.��� I have a problem with this.

I don���t doubt at all that life has become vastly better in the last couple of centuries, perhaps especially for oppressed groups such as workers, women and ethnic minorities. Instead, my question is: what progress has there been in the last ten years?

None at all, by one important measure in the UK. Real wages are now lower than they were ten years ago, and younger people have far less hope of ever owning property.

Of course, as Mill wrote, a stationary state of incomes need not imply stagnation in other aspects of human flourishing. But what progress have we had here recently? Yes, crime has fallen ��� albeit less so than in the 90s. But there can be little doubt that our political culture has declined. We���ve seen a rise in fake news (and misplaced allegations thereof), asymmetric Bayesianism, shrillness, intolerance and xenophobia.

Centrist and liberal values are under threat (though as John Gray points out, it would be misleading to call these ���Enlightenment values���.)

This, of course, is no coincidence. As Ben Friedman has shown, economic stagnations create intolerance and closed-mindedness. The anti-Enlightenment trends that Pinker identifies ��� ���tribalism, authoritarianism, demonization, magical thinking��� ��� are on the rise not because people have suffered a collective bang on the head, but because centrism is no longer putting money on the table. Brexit is, in large part, the product of stagnation and austerity.

From this perspective, I���m inclined to agree with Gray that celebrating the Enlightenment is an ���intellectual anodyne��� for centrists. This is because it misses the point.

Which is that the fact that a long history of progress has stalled is consistent with the Marxist narrative.

Marx saw that capitalism was a force for progress. It has, he wrote, ���accomplished wonders far surpassing Egyptian pyramids, Roman aqueducts, and Gothic cathedrals���, ���rescued a considerable part of the population from the idiocy of rural life��� and ���created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations.���*

But, he added, this would eventually cease to be the case. Capitalistic property relations would, he thought, eventually become ���fetters��� upon material progress. And, pace Friedman, a lack of material progress means moral and intellectual regress.

If this is right, liberal centrists are doing what Tom Paine accused Edmund Burke of: they are pitying the plumage of liberal values but forgetting the dying bird of the prosperity that fostered them.

Rather than simply assert the virtue of Enlightenment values, they must instead recognise that the threats to these are a product of capitalist stagnation. They must give us good reasons to believe this stagnation is temporary or ��� better still ��� come up with convincing ideas for rescuing capitalism. The fact that many of them acceded to Tory austerity means they have, so far, been unable to do this.

Unless they engage intelligently with the fact of capitalist failure, centrists will remain irrelevant. In fact, it might be that it is we Marxists rather than they who are the better defenders of values such as liberty and rationality.

* We must remember that capitalism was a force for progress in the 20th century in large part because it embraced anti-capitalist elements ��� a welfare state, mixed economy and progressive taxation ��� and began to stagnate as these elements were whittled away by neoliberalism.

February 22, 2018

Stable exploitation

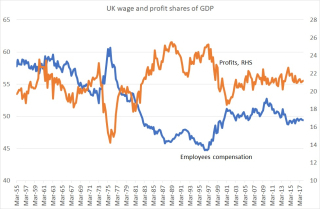

Was Kaldor right after all, at least for the UK? This is one question posed by today���s GDP data.

Kaldor proposed as a ���stylized fact��� that the shares of wages and profits in GDP are roughly stable over time. Today���s figures confirm that this has been the case in the UK, at least in recent years. They show that the share of profits in GDP has been stable at just over 20% since the early 00s. The share of employees��� compensation* has also been quite stable; it fell between 2009 and 2013 which was (arithmetically) the counterpart of higher taxes rather than rising profits.

Yes, we did see a massive shift in incomes from wages to profits between the 70s and mid-90s. But that was partly reversed in the late 90s. Since then, not much has happened to factor shares. This means the wage share is higher now than it was in the 90s and the profit share is lower.

All this is a stark contrast to the US. There, we���ve seen an increased profit share and increased (pdf) mark-ups since the 90s, and a decline in wages relative to productivity, all of which are symptoms of increased monopoly and monopsony (pdf) power.

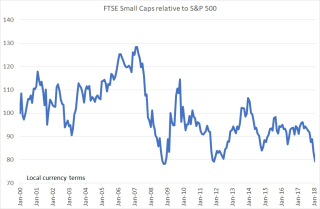

Stock markets tell us a similar story. Since the mid 00s US shares have significantly out-performed UK ones**. There are several possible reasons for this. One is that investors believe that US companies have more monopoly power than UK ones ��� what Buffett calls economic moats ��� which means their profits are more sustainable and this justifies higher valuations.

Quite why this should be is another story. One possibility might be that US firms are more intangibles-intensive and hence benefit more from economies of scale than their UK counterparts. As Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake have pointed out, intangibles can increase inequality.

Now, in saying all this I am not denying that the UK has a problem with inequality: a stable share of wages in GDP tells us nothing about the distribution of those wages. Nor of course am I denying that British workers are exploited. They are. But in aggregate they seem to be no more so now than in the 90s.

Instead, my point is that in the UK stagnant wages since the mid-00s has had more to do with flat productivity (until very recently) than with employers grabbing a bigger share of the pie. British capitalism is not like American capitalism. Whether this will remain the case is another matter.

* This includes employers��� pension contributions as well as wages.

** My chart compares the FTSE small cap index to the S&P 500 because small caps are a better measure of domestically-based stocks than the All-share index which is dominated by multinationals. Given that the small cap index has out-performed the FTSE 100 since the mid-00s, the UK���s under-performance would look even worse if we took the All-share index.

February 21, 2018

Hired: a review

For some time, I���ve asked that journalists leave the Westminster Bubble and look instead at ground truth. I���m delighted, therefore, that James Bloodworth has done just this. His latest book, Hired, describes his experiences of working on low wages ��� at an Amazon warehouse in Rugeley, a call centre in South Wales, as a care worker in Blackpool and as an Uber driver in London.

Of course, he���s self-aware enough to acknowledge that he���s a tourist. His experience necessarily misses a lot: the sense of despair that comes with knowing that low-wage work is for life; or the difficulties of juggling such work with care responsibilities, for example. However, when so much journalism consists of smears, prejudice and idle gossip whilst the voice of workers goes unheard, James��� story is essential reading.

It raises many issues, which should challenge both left and right. I���ll list just a few.

One, sad to say, is immigration: especially at Amazon, James is surrounded by Romanians. The issue here isn���t just the perception, fuelled by employment agencies wanting to screw down pay and conditions, that there���s a vast reserve army of migrants. It���s also perhaps that migrants contribute to a lack of class cohesion at work.

Secondly, James shows that a big problem for the low-paid is not just the level of wages but the insecurity. You can get by on the money James made, albeit joylessly. But there are many possible disturbances to these: ���mistakes��� in calculating wages (surprisingly common); changes in hours; unexpected expenses; or trivial misdemeanours at work that get you the sack. Any of these can force you into to the world of loan-sharks or homelessness.

For me, this strengthens the case for a citizens��� income: it provides security against such shocks.

Thirdly, low wages are unhealthy. James says he put on a stone whilst working at Amazon despite walking ten miles a day. The stress of work compels you to want a ���momentary morale boost��� such as a cigarette, chocolate or junk food. Add in the difficulties of fitting meals around irregular working hours, and the fact that low-wage work steals (pdf) cognitive bandwidth, and we���re left with the fact that demands on the poor to eat well are simply unrealistic.

What���s more, poverty is oppression. James says:

Whether it was the employment agency underpaying you, the job centre messing you about or the rent-to-own store trying to bamboozle you there was often this running battle with the authorities.

This continues in the workplace. James describes how workers face intense distrust and constant surveillance by either technology or ���petty fuhrers���.

This oppression, however, doesn���t come (directly) from fat plutocrats in top hats grinding the faces of the poor. Job centre staff who ���treat you like scum���, yobs who attack the homeless and the shop-floor tyrants at Amazon probably earn less than average wages. And yet they contribute massively to the misery of the worse-off. Yes, such people are under stress from those above them. But it���s possible that they have, in James��� words, ���internalized the objectives of their gaolers.���

And herein lies a depressing theme of Hired ��� the lack of class cohesion. James says: ���Thatcherism���s greatest success was probably in the gradual erosion of class solidarity.��� You get no sense in his book that his colleagues are active supporters of Corbyn or (worse still) that they have dense networks of friends or family to help them through the hard times.

Granted, there���s a danger here of romanticizing the past. The lack of class solidarity was a theme of Robert Tressell���s Ragged Trousered Philanthropists and we must remember that trades union militancy was used to ���preserve differentials��� and to support Enoch Powell, as well as for more benign ends. Nevertheless, this reminds us of Marx's biggest error - the belief that class consciousness would increase over time.

Rightists like to tell us that there���s more to poverty than a lack of money. They might be right, if not in the way they intend.

February 19, 2018

When the impartial spectator is missing

Is good behaviour more fragile than generally supposed? For me, this is the question posed by the unpleasant controversy sparked by Mary Beard���s tweet:

I do wonder how hard it must be to sustain ���civilised��� values in a disaster zone.

One interpretation of this seems to me plain wrong ��� that it is an attempt to justify the wrongdoing at Oxfam.

Another interpretation is that there���s an undertow of racism here. Even in quote marks, that word ���civilized��� echoes imperialist talk of white men ���going native��� ��� of ���white aid workers as Mr Kurtz figures caving in the strain of ���The horror, the horror������ in Priyamvada Gopal���s words.

But I wonder, might there be another reading of that tweet? We could read it as meaning that decent behaviour ��� civilized behaviour if you must ��� is not hardwired into us, and that many of us have darker tendencies

One reason for this, as I said recently, lies in a mix of ego-depletion and self-licensing. We cannot maintain full self-control for long under stress: we have to let off steam. And a belief that one is a good person doing good gives one a self-licence to behave badly. If you've just saved a few lives, you can convince yourself that it's OK to see a young prostitute, just as colonialists justified greed and brutality to themselves in the belief they were bringing Christianity to ignorant people, for example. Self-serving biases are powerful things.

But there���s something else.

It lies in Adam Smith���s idea of the impartial spectator. What keeps us behaving well is the suspicion that there is someone watching us. When we play outside as children, we might think we are only with other kids. But often we���re watched by family friends or neighbours, so our parents learn of our misbehaviour. That keeps us honest. As D.D. Raphael writes in his exposition of Smith:

The approval and disapproval of oneself that we call conscience is an effect of judgments made by spectators. Each of us judges others as a spectator. Each of us finds spectators judging him. We then come to judge our own conduct by imagining whether an impartial spectator would approve or disapprove of it (The Impartial Spectator p 34-5)

When this impartial spectator is fully internalized it becomes God or conscience. But it isn���t always so internalized. When it isn���t, it is the fear of actual real spectators that keeps us well-behaved. There���s always the danger that our spouses or bosses will hear of our misdeeds.

When we go overseas, however, we leave the most influential spectators behind, which lessens the constraint upon us. The only observers we have are foreigners who are, at best, less likely to report us to our employers or partners*.

The result of this is that there is a massive tradition of white men behaving badly outside their own countries, from imperialist brutalities to war crimes. We see faint echoes of this today. Men who go on business trips often behave worse than at home; West Brom footballers are more likely to steal cabs in Barcelona than Birmingham; there���s a reason why stag parties go to Amsterdam or Prague rather than the fiancee���s house; and what happens in Vegas stays in Vegas. As Paul says, ���rampant power to abuse was part of the ���expat��� tradition, even folklore, alongside its hard-drinking culture.���** Heart of Darkness and Lord of the Flies both speak to this tradition.

In other words, what we call ���civilization��� is not some property of individuals. It is, instead, emergent; it arises from social pressures upon us and might evaporate when those pressures are absent, depending upon how much the impartial spectator is internalized.

Which brings me to a paradox. Although Professor Beard���s tweet has been interpreted as having an undertow of racism (perhaps rightly if inadvertently) it might also bear a very different interpretation - that white men are not as ���civilized��� as they pretend. And there���s a lot of history to support such a view.

* There is, of course, often a baser motive for discounting their opinion, which is that the opinion of people who aren���t like us counts for less ��� which is one reason why we should be so wary of ���othering��� other people.

** It shouldn���t need saying, but I fear it does: I���m not claiming any moral equivalence between these examples but merely suggesting that a similar mechanism is at work.

February 16, 2018

Labour and the Customs Union

Simon says Labour should stop faffing around and declare support for the UK staying in the Customs Union. I���d like to amplify and caveat this.

First the amplification. Labour is missing a trick here. It should be linking its policy on Brexit to its wider critique of British capitalism.

It should be pointing out the raw fact that Germany exports much more to countries outside the EU than the UK: half as much again (per person) to the US; 2.5 times as much to Japan; almost four times as much to China; and so on.

This tells us that it is not membership of the Customs Union that is stopping us from exporting more. Instead, the obstacles lie in the short-comings of British capitalism: poor management; lack of entrepreneurial spirits; insufficiently skilled workers; lack of investment; credit constraints; financialization; a lack of price competitiveness; and so on.

Labour should be highlighting these, and its policy responses to them. It should be saying:

Rather than wasting time on free trade deals, we should stay in the Customs Unions and focus on fixing Britain���s real economic problems, not the imaginary ones that exist in Brexiters��� fantasies. Only by doing so can we make the UK the truly outward-looking global trading nation that Boris Johnson claims to want.

That said, here���s the caveat: Labour���s vagueness on Brexit is much more forgivable than the Tories���.

What I mean is that there some Labour issues and some Tory issues. Tories, for example, have traditionally been more interested than Labour on defence, as there tend to be fewer military minds on the left (which reflects no credit on the left). But Labour has been stronger on health and welfare policy, for example.

Brexit, however, is almost entirely a Tory policy. I don���t just mean that Brexiters tend to be on the right. I mean that it has for years been a much more salient issue for them than it has for the left. For some it has been one of their top priorities for years. Most of the Labour party (with some exceptions!) by contrast made their peace with the EU in the 1980s and didn���t give it much more thought. I, for example, had barely considered the UK���s role in Europe until a few months before the referendum. I suspect that even most Lexiters have regarded Brexit as a bit like many lefties regard republicanism; if the issue arises, they support it, but they have higher priorities.

Labour���s ambivalence about Brexit is, therefore, understandable. It has pretty much no tradition of even thinking about the subject. For some Tories, however, Brexit has been their desire for 30 years. One would expect them, therefore, to have somewhat more than the vague hint of a slight clue about what it entails.

So yes, by all means criticize Labour���s vagueness. But remember, Brexit is above all a Tory mess. It���s their shit; they should shovel it.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers