Chris Dillow's Blog, page 36

November 27, 2018

Strategic vs parametric thinking

Brad De Long makes an important point when he says that rational thinking depends upon context, and we must always ask: ���are we playing some kind of game against nature, or are we playing against another mind?��� If it���s the former, then standard parametric thinking is appropriate (max U subject to constraints). If it���s the latter then we are in the realm of game theory.

You might think the distinction obvious. Many people, however, fail to make it. As Meir Statman says:

Think of trading stocks, bonds and other investments as a trading race. Traders who commit framing errors frame the trading race as between them and the market���Traders possessing human-behaviour and financial-facts knowledge frame trading correctly as against traders on the other side of the trades. (Finance for Normal People, p40)

An especially egregious example of this is the IPO anomaly, the tendency for newly-floated shares to do badly in the three years (pdf) after they come to market. One reason for this is that investors think they are playing a game against nature when in fact they are playing against another mind ��� those on the other side of the trade. They fail to ask: ���if this is such a good investment, why are its owners selling it?���

David Navon calls this mistake the egocentric framing error ��� the tendency to think only from our own point of view and to neglect how others are thinking. Bad chess or poker players, for example, consider only their own strategies without asking what their opponents are planning. In traffic jams we often try to switch lanes without getting any further because we fail to see that others are behaving just like us. And bad negotiators consider only what they want without thinking about their counterparty���s strategy: as Roger Fisher and William Ury show in Getting to Yes (pdf) good negotiators put themselves in the shows of those on the other side of the table. One reason (of many) why we���ve ended up with a bad Brexit deal is that the government failed to do this.

There are other examples of egocentric framing, described in Jerry Muller���s The Tyranny of Metrics. Managers and politicians who set targets without seeing that they can be gamed or misused are committing this mistake. They believe they are in a parametric environment when in fact they���re in a strategic one. They���re attributing agency only to themselves and not to others.

Perhaps this point broadens. Maybe there are particular types of people who are especially prone to egocentric framing. Those who are traditionally the subjects rather than objects of history have historically had less need to treat others as agents with their own strategies ��� especially if those others have been cowed into submission, Men have traditionally had little need to think about gender, or the posh about class, or white people about race. They haven���t therefore had the need to ask David Mitchell���s question: ���are we the baddies?��� Those on the dirtier end of these sticks haven���t had such luxury. As Robert Burns wrote:

O wad some Power the giftie gie us

To see oursels as ithers see us!

It wad frae mony a blunder free us,

An' foolish notion.

November 22, 2018

Blinded by ideology?

Andrew Neil tweeted yesterday that low gilt yields were a sign that ���at least the credit markets still have confidence in the country��� to which I replied that they were, to the contrary, a sign that markets expect low economic growth, partly thanks to Brexit. This was a cue for a mini pile-on by Neil���s Brexiter followers claiming that low yields are indeed a sign of improved creditworthiness.

You shouldn���t need me to tell you this is pish. The government���s creditworthiness has never been in question, except perhaps in the fevered imaginings of a few hysterical austerians. And nor could it have been. A government that can print its own money can always repay its debts: this is why comparisons between the UK and Greece are idiotic. The only question concerns the value of the money that gilt-holders will get. There���s no credit risk, therefore, only inflation risk*.

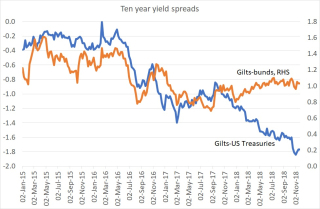

My chart shows that gilt yields are lower relative to their US and German equivalents than they were before the referendum. It would surely be silly to infer from this that the UK government���s creditworthiness has improved relative to Germany���s or the US���s. It���s more plausible that markets believe our growth prospects have worsened ��� though I���m not sure Brexit is wholly responsible for this.

Other indicators of markets��� ���confidence in the country��� tell a different story from what Neil would have us believe. Sterling���s trade-weighted index is lower than it was pre-referendum. And even ignoring currency effects, the All-share index has slightly under-performed the rest of the world: since just before the 2016 referendum the All-share has risen 17% in sterling terms whilst MSCI���s world index is up 21% in dollar terms. All this is more consistent with a deterioration of our relative growth prospects than with increased ���confidence in the country.���

In truth, no Brexiter claimed during the referendum campaign that Brexit would improve the government���s creditworthiness. And nor should they have. What Neil and his fanboys are doing is the equivalent of shooting at a wall and then painting a target around the bullet-holes and claiming to have hit a bulls-eye.

This poses the question: why do some Brexiters fell the need to argue the unarguable? They have instead two different claims they could make. They could argue that stock and bond markets are wrong to take so gloomy a view of the UK���s growth prospects. Or they could argue ��� more tenably I believe - that less prosperity is a price worth paying for sovereignty and freedom.

I���d be sceptical even of the latter argument. But it���s not manifestly absurd, which is far more than can be said for the claim that Brexit has improved the government���s creditworthiness.

Which poses the question: why do some Brexiters feel the make to make such silly claims?

It���s become fashionable to say it���s because they are blinded by ideology.

I disagree. We all have ideologies. Yes, even you centrists. But we are not all blinded by it. In fact, in some ways ideology can make us wiser. It can motivate us to study a problem: many of us became economists, for example, because we hated the unemployment and poverty we saw in our youth. And it can sometimes actually improve our vision. My Marxism has made me a less bad economist than I���d otherwise be because it means I have no dog in a lot of fights about economics.

Instead, I suspect that what we have here is not so much the result of ideology as of fanaticism. Fanatics want to believe that all evidence supports their side and that there are no trade-offs. And the wish is father to the belief.

But it���s the fanatics we hear from. They���re the ones on Twitter and who get into the BBC and newspapers whilst the more level-headed ��� almost by definition - don���t make the effort to do so; there are Brexiters who agree with all I've said above. There is, therefore, a form of adverse selection in favour of bad ideas. As Edmund Burke said:

Because half a dozen grasshoppers under a fern make the field ring with their importunate chink, whilst thousands of great cattle, reposed beneath the shadow of the British oak, chew the cud and are silent, pray do not imagine that those who make the noise are the only inhabitants of the field.

* In truth, this has increased recently: the ten-year breakeven inflation rate is now 3.3 percentage points, compared to 2.6 percentage points in the six months before the Brexit referendum though I���m not sure how much Brexit is to blame for this.

November 20, 2018

Against foxes

Nick Cohen makes a good point:

Political correspondents, who couldn���t find a big picture in a multiplex, buzz around Westminster hyperventilating about the number of letters sent to the 1922 Committee, and the replacement of minister X with junior minister Y, as if it mattered in the slightest.

The clich�� is right. It is indeed easy to miss the wood for the trees. The fox (pdf), who knows many things, can indeed miss the big picture which the hedgehog (who knows one thing) sees. Those same political correspondents��� - despite or perhaps because of their knowledge of detail and minutiae - failed to anticipate Brexit and the rise of Corbynism.

It would, however, be wrong to single out political correspondents here. Nick���s point generalizes. Take, for example, finance. Advisors are often good foxes: they know many things. It���s better, however, to know one big thing ��� that active fund managers generally do not earn their fees (pdf) ��� and so simply hold market tracker funds.

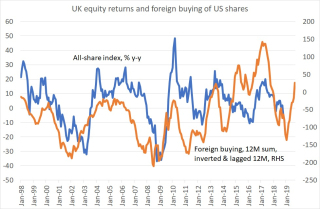

A similar thing works in forecasting. Sometimes, it���s better to know one big thing. For example, if you���d wanted to know where stock markets were heading this year, one fact would have told us ��� net foreign buying of US equities. When this is high (a low point on my chart) it predicts that markets will fall in the following 12 months*. High buying last year predicted that the market would drop this. And yes, this indicator also warned us of the 2008 financial crisis. Knowing one thing would have served us better than knowing many things.

In saying this, I���m echoing Gerd Gigerenzer. Simple heuristics (pdf) ��� knowing one robust and relevant thing ��� beat knowing lots of little irrelevant ones. Big Facts matter. Knowledge, prediction and explanation are three different things: you can have one without the other two.

The issue here is whether we can distinguish between noise and signal. A mastery of detail can mean that you have full knowledge only of noise. This is handy for pub quizzes, which is no small thing (I write as a member of the team that���s top of division two of the RIQL) but it can blind you to what���s important. You have only cargo cult expertise. One reason why I���ve paid little attention to the day-to-day developments in Brexit negotiations (progress might not be the mot juste) is that I���ve not known what���s noise and what���s signal.

Rogue companies exploit this. When they are under investigation from regulators or the police they often boast that they are cooperating fully. What they mean is that they are handing over terabytes of data and hoping the authorities will miss the wood for the trees.

You might think that in siding with hedgehogs against foxes I���m disagreeing with Philip Tetlock who has shown that foxes make better predictors than hedgehogs. I���m not sure I am. We mean different things when we distinguish between the two. I���m thinking of the distinction between those who know lots of small things and those who know one big relevant one. He instead uses it to differentiate between empiricists and grand theorists. In that sense, I agree with him. The problem with that sort of hedgehog is that the one big thing they know is sometimes wrong. You might have heard of such people.

* The reasoning here is simple. Foreign buying is an indicator of investor sentiment (pdf): high buying betokens high sentiment. And when sentiment is unusually high, it tends to mean-revert downwards, thereby dragging prices down.

November 16, 2018

Why the left needs "bottom"

Conservative men of a certain age used to speak approvingly of some men (it was always men) as having ���bottom���. By this they meant a combination of a moral code and loyalties that gave them a solid reliability.

I was reminded of this by these words of John McDonnell:

We���ve got to convert ordinary members and supporters into real cadres who understand and analyse society and who are continually building the ideas.

This is absolutely bang right.

Underlying his words is a fear ��� that the massive current popularity of Corbynism might just be a fad.

There���s ample precedent here. The revolutionary ideals of the 68ers faded as they acquired careers and (cheap) property. The Greens won 15% of the vote in 1989, but that soon vanished. And of course there are countless people who, in Christopher Hitchens��� words, made the stagger from left to right ��� and who rarely became less employable as a result. Personally, I wouldn���t stake my wealth upon Aaron Bastani or Laurie Penny being vocal leftists in 30 years��� time.

The vogue for Corbynism could go the same way. Although McDonnell is giving the programme real and often inspiring economic content, there���s danger that Corbynistas themselves are motivated by what James Bloodworth calls ���a vague and muddled ideal���, a backlash against ���neoliberalism.��� If your leftism consists only of an emotional spasm, a belief that Tories are ���evil���, it will not long survive contact with real human beings.

Nick Cohen has long complained that leftists have lost touch with their better values and adopted a ���my enemy���s enemy is my friend��� mentality that has seem them ���excuse antisemitsm, misogyny, tyranny, and obscurantism, as long as the antisemitic, misogynistic, tyrannical obscurantists are anti-Western.��� I know many of you reject this account. But in a sense it speaks to what McDonnell fears ��� that a leftism which is just childish rebellion cannot last long or grow large.

It���s in this context that the left needs ���bottom��� ��� ballast that stops it drifting with the tides of fashion and instead becomes a genuine solid force for change.

Classical Marxists understated the problem here. They thought workers would be so desperately poor and exploited that they���d have nothing to lose but their chains and so would become radicalized. They were wrong. Yes, one factor behind Corbynism is that erstwhile ���middle-class��� jobs have become proletarianized; professionals have both lost some autonomy at work and become unable to afford a house. Resentment alone, however, is not a strong enough base for lasting leftism. It might not survive career progression and more affordable housing.

It���s in this context that McDonnell is right to say the left needs an understanding of society. Of course, it would take far too long to spell out exactly what this would consist of. For me, a key principle here is that of complexity. Inequality ��� of power as well as wealth - does not exist and persist because the rich are evil. It also happens, as Marx recognised. because of impersonal forces which operate with only a little input from people���s intentions. Capitalists��� influence over the state, for example, happens because politicians want to create jobs and so need to maintain business confidence; support for inequality exists not just because our media is biased but because ideology is endogenous; exploitation occurs not (just) because capitalists are greedy but because competition forces wages and working conditions down.

Equally, the capitalist crisis is the result not just of ���greedy bankers��� ��� everyone would like a few quid more ��� but of impersonal factors causing a lack of capital spending and hence stagnation in productivity and real wages.

A lasting, well-rooted leftism requires an understanding of forces such as these ��� of why capitalism does not work as we would wish it to. Moralizing is nowhere near enough. The problem is that there are pitifully few institutions that enhance understanding and several powerful ones that actively militate against it.

November 15, 2018

Angry Brexiters

Brian Cox asks a good question:

The thing I don���t understand about these Conservative MPs is that they are such angry people. They haven���t done badly out of Britain - they aren���t on the receiving end of their own policies. And yet they want to smash everything up. The EU, The Union and now their own party.

It���s no coincidence that many of those he has in mind such as Rees-Mogg and Johnson - though we might add Farage and Banks ��� come from posh backgrounds. We know that our preferences adapt (pdf) to our circumstances. As Amartya Sen has written, ���deprived people tend to come to terms with their deprivation���: Daniel Neff has shown how this is true for some of the poorest people in the world. Just as the poor resign themselves to their wretchedness, however, so too do the wealthy take for granted their privilege. Rather than rejoice in their advantages, they are irked by the small stone in their shoe. Just as the rich banker gets the hump with a ��1m bonus if he expected more, so Brexiters are angered by slight (and often imaginary) infringements on their freedom from the EU.

In this sense, demand for Brexit is a little like white male resentment. Both are reactions against challenges to the privileges to which one has become accustomed.

There���s also a sense of entitlement here. Just as posh folk sometimes apply for jobs for which they are ill-suited ��� most famously David Cameron becoming PM because he thought he���d ���be rather good at it��� ��� so they noisily demand the removal of all obstacles to their whims.

All this is in fact at least as old as the Bible. It is mechanisms such as these that give us the Matthew Effect:

For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance: but from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath.

Socialization also matters. If you���ve got so many advantages in life, especially from a young age, you���ll be less aware of the importance of trade-offs ��� that, for example, academic and career success will estrange you from your family and cause loneliness. You will therefore not be as alive as the rest of us are to the words (pdf) of Isaiah Berlin:

The notion of the perfect whole, the ultimate solution, in which all good things coexist, seems to me to be not merely unattainable ��� that is a truism ��� but conceptually incoherent; I do not know what is meant by a harmony of this kind. Some among the Great Goods cannot live together. That is a conceptual truth. We are doomed to choose, and every choice may entail an irreparable loss.

They therefore fail to appreciate sufficiently that there are trade-offs between sovereignty and prosperity, or between controlling our borders and observing the Good Friday Agreement.

Such socialization-induced blindness isn���t however merely the product of upbringing. It���s also the result of recent political history. Throughout their adult lives Brexiters have got what they wanted from politics ��� lower taxes, the defeat of trades unions and victory of neoliberalism. Even the Labour government did not seriously challenge the power and prestige of the wealthy.

Victory, however, breeds complacency. It led Brexiters to forget what we Marxists have known all along ��� that there are some interests which the state lacks the will or the capacity to promote. They were therefore unprepared for the hard work of implementing Brexit. They failed to appreciate that politics sometimes requires something more than bluster. Their anger is a form of displacement ��� attacking others for what are in fact their own inadequacies.

November 13, 2018

Beer, & economic determinism

Devarshi Lodhia has a nice piece on the decline of the pub. I wonder, though: to what extent are the social and cultural changes that have contributed to their decline a product of raw economics.

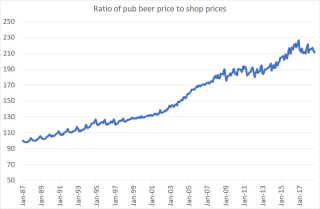

My chart shows what I mean. It shows that since the mid-80s the price of beer in pubs has doubled relative to its price in shops. Today, for example, you can get 12 cans of Lager at Tesco for ��8.50, which means that a pint of beer is 4.2 times as expensive in pubs as in shops. 30 years ago, it was only twice as expensive.

Millennials who are going to dessert parlours or staying home and drinking whilst playing Fifa therefore look like they are responding to price signals. The ONS tells us that increasing numbers of young folk are teetotal: 23% of 16-24 year-olds claim to be, compared to 16% of 45-64-year-olds.

Whilst this behaviour is harmless, there might be a nastier effect of this price change. When I was a 15-year-old kid, I���d drink in pubs. Today, higher prices plus tougher law enforcement means teenagers don���t go to pubs: even Wetherspoons has a door policy. They drink instead in parks which is more dangerous: there���s no barkeep to sling them out when they���ve had too many or to have a word when boys pester drunken girls.

There are two important mechanisms here.

One is peer effects: if your mates go to the pub, so do you. These create multiplier effects: if a few people stop going to pubs, others follow. Hence the large number of pub closures.

The other is habit formation. When we were kids getting served in a pub gave us a frisson of excitement and achievement. We came therefore to associate even the most mundane pub with good times, and this keeps us going to them today*. If young people don���t get that kick, and don���t get into the pub-going habit, they���ll stay out even if they get rich enough to afford to go.

In this way, short-term changes can have long-term effects. This suggests that pub-going will continue to decline as older pub-goers die out and are not replaced.

Now, it���s possible that the cultural changes that keep more young people out of pubs might have happened anyway**. What I suspect might be more likely, however, is that what we have here is a case of economic determinism: price changes cause cultural change. Which is why economics matters.

* This mechanism is much the same as Adam Smith���s account of conscience. The fact that aunts and uncles watched us whilst we were children inculcated into us a sense that an impartial spectator was overseeing us without us knowing it��� a sense that persists throughout our lives.

** The obvious counter-argument to this claim is that if there had been a decline in demand for drink in pubs then their relative prices should have fallen. The counter-argument to that, though, is that tax changes and rent rises prevented this.

November 9, 2018

Contrarians in public life

What role, if any, should contrarians play in public life? This is the question posed by the appointment of Sir Roger Scruton as housing tsar despite (or perhaps because of) his unconventional opinions on eugenics, date rape and gay rights.

The issue here is not a left-right one. We could ask the same question of John McDonnell: does his support of the IRA disqualify him from office?

In fact, for me the analogy is a quite close. Both men have valuable ideas. McDonnell���s ideas on fiscal policy and worker ownership are good. And Sir Roger is a rare rightist who can (sometimes) think and write well and who is fascinating for being a conservative whose mind isn���t addled by Brexit or free market simplicities: I���d recommend his books Gentle Regrets and England: an elegy. (Perhaps there���s another parallel; both men���s most deplored utterances are the products of their class, age and environments.)

The case for excluding such men is that the expression of bad ideas itself betokens a lack of judgment. Just because you believe something does not mean it should be said. The ability to shut the fuck up is much to be prized.

But, but, but. Excluding such men doesn���t just risk depriving us of talent. If people know that heterodox ideas will carry heavy costs we���ll end up with men falsifying their preferences ��� using politically correct language to disguise racist or sexist behaviour: Harvey Weinstein, remember, has been a keen supporter of liberal causes.

What���s more, if we select people for having uniformly orthodox opinions we���ll end up not with office being held by those with phronesis, but by poker-up-the-arse careerists who are too dull or stupid to challenge our managerialist conventional wisdom. One McDonnell or Scruton is worth a dozen of them.

Everybody is irrational about some things. Scruton and McDonnell join the long list of people such as William Shockley, Richard Dawkins, Larry Summers, Vicky Pryce, Bobby Fischer, Glenn Hoddle and James Watson ��� people of brilliance who also have made some terrible decisions. If you���re looking for people of uniformly sound judgement, you���ll find nobody but crooks, dullards and disappointments. In this context, I'd rather judge people by their best rather than their worst.

And then, of course, there is Mill���s famous point ��� that we need contrarians, even if they are wrong, to sharpen our perception of the truth:

The peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.

Note that the silencing here need not be legal suppression; it could be via the tyranny of the majority, or simply self-censorship.

But again, there���s a but. Contrarians don���t always (or even often) provoke intelligent debate. They can be as tiresomely conformist as the dullest careerist: is there a more predictable writer than Brendan O���Neill? And what looks like contrarianism is often no more than mindless tribalists whining about political correctness gone mad zzzzz: despite my analogy, how many defenders of Scruton would also defend McDonnell?

If all this sounds inconclusive, that���s because it is. My hunch is that Scruton should not be housing tsar not so much because of his regrettable ideas on some things, but simply because his merits do not extend to especial expertise on housing. This, though, does not solve the underlying questions: how tolerant should we be of otherwise useful people in public life who say things we hate? What is the proper place for those who question society���s flawed conventional wisdom? What, if anything, can we do to get a better and more diverse type of contrarian?

November 8, 2018

Stabilization policy with ignorance

Eric Lonergan���s good discussion of fiscal rules has triggered an intemperate debate about MMT. For me, though, it poses a question: from which fact(s) should thinking about macro policy begin?

For old-style Keynesians, the fact was that labour markets could not be relied upon to clear. For new classicals, it was that people were rational maximizers. I want to suggest a different fact ��� that recessions are unpredictable.

Prakash Loungani has shown that both private and official forecasters ���miss the magnitude of the recession by a wide margin until the year is almost over���. In February 2008 for example ��� after the recession had begun ��� the Bank of England attached only a slight probability to GDP falling when in fact it fell more than 6% in the following 12 months*.

Exactly why this should be is a question for another day: I suspect it���s because recessions have micro-level origins which are magnified by network (pdf) effects between heterogenous firms.

Whatever the reason, this Big Fact has a devastating implication. It warns us that there are severe limits upon what demand management can achieve, whether it be through fiscal or monetary means. This is simply because there���s a lag between policy and outcome. Fiscal or monetary policy can boost demand once it has fallen. But it cannot reliably prevent all recessions. This point applies to conventional as well as unconventional policy. By the time the Bank of England knows there is a sufficiently deep recession to require (say) a helicopter drop, the recession will be well under way.

How can we respond to this?

We could follow Robert Lucas and say it���s a non-problem because the welfare costs (pdf) of economic fluctuations are trivial. Most of you, though, would resist this, and I think (pdf) rightly so.

Or policy-makers could reject conventional macroeconomic forecasting and place more weight upon the yield curve (pdf) to tell us the probability of recession. This, though, is inviting us to be smacked in the face by Goodhart���s Law.

This leaves a third response: we need better automatic stabilizers.

The obvious possibility here is more progressive taxation and a higher welfare safety net. Another possibility is for Shiller-style macro markets to enable those most exposed to the risk of recession to buy insurance: this requires state support for such markets. A third possibility is one suggested by Eric: a sovereign wealth fund. Insofar as this holds overseas assets, it would help diversify local UK economic risks, and would rise as sterling falls.

It���s in this context that a Job Guarantee becomes attractive (pdf). It would provide schemes which expand to create jobs in recessions, and contract as private sector jobs are created in the subsequent upturn. It���s another automatic stabilizer.

Now, there are issues with a JG, not least of which are administrative ones: how do we identify what work needs doing? How can we ensure a JG doesn���t deteriorate into demeaning workfare under rightist governments? And so on. Such problems are a case for thinking about a JG now, and for rolling it out in good times, so that difficulties can be addressed before the scheme needs to be scaled up.

We should regard a JG not as a faddish idea of some sect ��� although that it how it is sometimes presented ��� but rather as one of a suite of possible policy responses to one of the fundamental facts of the human condition: our inability to reliably foresee the future.

* It���s unclear that heterodox economists foresaw the 2008-09 recession; permanent warnings of the risk of recession are of limited use for the purposes of macroeconomic stabilization.

November 7, 2018

Not wearing a poppy

I agree with Harry Leslie Smith. I too am increasingly disinclined to wear a poppy.

The thing is that the nature of national remembrance has changed. For the first 60+ years after it began it was personal for pretty much everybody. Well over a million British soldiers and civilians were killed in the two world wars. Almost everyone therefore had lost a friend or family member. And everybody knew old soldiers who remembered the horrors of war and often still bore the mental and physical scars.

But this is no longer the case. Almost nobody under the age of 90 fought in World War II. For increasing numbers of us, war is no longer personal: our grandparents who suffered in it have left us*.

My personal ties to war are confined to the death of a great uncle at Ypres and two friends who served in Northern Ireland ��� not that everybody wants to remember the latter.

Of course, there are many for whom this is not the case, who remember friends, husbands and sons killed in the Falklands, Iraq, Ireland or Afghanistan to name but a few. It would, however, be intrusive and even abusive for me to pretend to share their grief ��� which of course they bear every day, not just on Sunday. I respect it and sympathize with it. But it is their burden, not mine. To pretend otherwise is a con, a narcissistic flaunting of ersatz emotion.

One or two generations ago, Remembrance Day was about strong people struggling with horrors and grief we cannot imagine. For some, this is still the case. But for many others, it is a display of emotional incontinence.

There���s a paradox here. Although the memory of war is becoming different for us all, there are increasing pressures to conform by wearing poppies: those who refuse to do so, like James McClean or Charlene White, face abuse**, some of it racist. And this, I suspect, is deeply hypocritical. How many poppy fascists support benefit cuts for ex-soldiers and piss on the addicted homeless ones? It is abstract dead soldiers they claim to respect, not real living ones.

Of course, remembrance is not just a personal matter. There is such a thing as collective identity. We can remember our dead as a nation even if many of us individually have no memory of specific victims of war.

But here again, there are hypocrisies.

One is that Remembrance Day is linked with nationalism: how many union jacks will we see on Sunday? And yet it is nationalism that contributed massively to the deaths of those we claim to remember.

Another is that war is not some tragedy that befalls us by unavoidable accident. It is the result of policy error. The error might be the direct one of choosing to go to war, as in Iraq. But it���s also due to a failure to deal with the complex causes that led to WWI or to the rise of Hitler. If there had been better economic management ��� less harsh reparations, no hyper-inflation in the early 20s, no Great Depression ��� we might not have had Hitler and WWII. Von Clausewitz was right: war is the continuation of politics by other means.

It���s sometimes said we should wear poppies with pride. We should, in the sense of having pride in those who served their country. But we should also wear them with shame ��� same at the political mistakes that led to those wars.

Memory, if it is to be anything more than an empty gesture, must mean learning. The lesson of our war deaths is that politics is a deadly serious business. It is a job for serious people who must avoid egregious errors.

This, of course, is a lesson we have not learned. The Chilcot report describes how the errors leading to the Iraq war were ones which should have been well-known to anybody with a passing knowledge of decision theory. And the BBC executives who enforce poppy-wearing to the extent of expecting contestants on Strictly Come Dancing to wear one on their gym kit also give us TV shows in which politics is just fact-free banter between men who went to the right schools. They persist with the Old Lie, that politics a game for jolly good chaps in which ��� notwithstanding the imbecilic martial metaphors ��� the stakes are low. It���s not just our war dead who prove this to be an illusion: so too does Grenfell Tower and the thousands killed by austerity. And yet our rulers and media don't heed the message.

Now, none of this is to say we should not have public commemorations of the war dead. We should. My problem is that these have been taken over by hypocritical posturing.

* Not that it was all suffering. My grandad ��� like many I suspect ��� had quite fond memories of the war.

** Not, I suspect, from old soldiers themsleves. Whenever I give to British Legion collectors but refuse the poppy, I sense a respect for my decision.

The picture is of 603 crosses in Oakham churchyard, one for every Rutlander who died in WWI.

November 4, 2018

The triumph of the liberal technocrats

Brexiters have something in common with anti-pornography campaigners. That���s the idea that struck me whilst reading Alwyn Turner���s account of the failure to establish public harms that result from porn.

What we have in both cases are failed attempts to translate arguments into consequentialist terms. The best case for Brexit is an intrinsic one ��� that it���ll give us a sense of independence and sovereignty. When its advocates try to argue that it���ll also make us better off, they make fools of themselves. Similarly, many of those who oppose pornography are motivated by intrinsic considerations ��� the belief that a society in which pornography looms large is a coarser and uglier one than one in which it doesn���t. When they try to cite public harms of porn, they push their case further than the evidence merits.

The same is true for opponents of immigration. A disquieting sense that immigration is changing society is one thing. It is when this leads to an argument that immigration does economic damage that they go wrong.

Some of you might add that egalitarians often do a similar thing. Rather than make a case for greater equality as an intrinsic good, we often make Spirit Level-type consequentialist arguments.

What���s going on here?

Part of the story is a form of halo effect. We tend to believe that good things go together to a greater extent than is the case, as do bad things: the hero in the films is better looking and a better shot than the villain. We thus overstate the case to which intrinsic goods also have good consequences.

This is exacerbated by the tendency for political arguments to be made by fanatics ��� people who, in overstating their case, become counter-advocates for their position.

Something else, though, is happening. This urge to express all arguments in consequentialist terms is an admission that liberal technocracy has won. The only acceptable arguments for any policy, it is believed, are consequentialist ones ��� ideally, along the lines of making us materially better off. And everybody seems to accept Mill���s harm principle, and thus argue for bans on the ��� often elusive ��� grounds that the activity in question does indeed impose harms onto others.

Although the country has had enough of experts and there is a backlash against liberal elites, liberal technocratic philosophy has won.

I wonder, though: did it really do so through explicit argument? If so, when and how exactly? Or did it win by default? Maybe Alasdair MacIntyre was right. We���ve lost the ability to make coherent moral arguments and so have retreated into a (pseudo-)scientific managerialism. To his credit, Ben Cobley seems pretty much the only person to see this, and to see that there are alternative forms of argument here.

This retreat, however, does not solve fundamental ethical problems. If we are imposing costs onto others so that others may benefit, the nature of those costs and benefits are second-order. Whether they are financial or the fulfilment or frustration of some preference, all the issues with utilitarianism remain: under what circumstances may we impose hurt upon some to benefit others?

Yes,it could be that people adopt liberal consequentialist arguments for tactical reasons - that these are a means of reaching inter-subjective agreement which other philosophical positions cannot. I'd like to believe so, but the shrillness and partisanship of so much debate makes me suspect this isn't always the case.

What���s more, I���m not sure how important it is that advocates of some of these positions cannot articulate them clearly. If you ask Brexiters why they value sovereignty, or anti-immigrationists what exactly their disquiet is, you often don���t get a very coherent reply/ But so what? Michael Polanyi had a point when he said that tacit knowledge, gut feel and instincts are important too.

Now, in saying all this I���m arguing against my own beliefs. Arguments that we should accept less prosperity in exchange for greater sovereignty or less migration leave me cold. And instinctively, I���m on the side of free movement and freedom to see what you want. I'm glad the liberal technocrats have won.

My perspective, though, is a partial one. My upbringing gave me anti-authoritarian instincts and a belief that prosperity matters ��� beliefs hardened by my economics education. What surprises me is that these views are, implicitly, so universally shared. And as Mill himself said, it is attitudes that we all share, often without doubt, that we must question.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers