Chris Dillow's Blog, page 34

February 5, 2019

Obstacles to full employment

Is full employment sustainable? For me, this is one question posed by the row between Richard Murphy and Jonathan Portes and Simon Wren-Lewis over Labour���s proposed fiscal rule.

Richard describes the difference between them thus:

I am seeking a stable, sustainable economy with full employment. They are seeking the restoration of the model of central bank monetarism that existed from 1999 to 2008 in the UK, with well-known consequences.

This is because Portes and Wren-Lewis want to use fiscal policy to inflate the economy away from the zero lower bound, so that interest rates can again be used for macroeconomic stabilization.

Richard���s desire, however, runs into a problem. Economists generally agree that at some point high employment will trigger rising inflation. What this point is is an empirical question. The fact that inflation has been quite stable since the early 90s whilst unemployment has not been makes me suspect it might be further off than the Bank of England thinks, but that���s by-the-by. Which poses the question: what should we do to curb this inflation?

The conventional view, which Simon and Jonathan take, is to raise interest rates. But Richard and MMTers are right to say this isn���t the only possibility; in theory tax rises are also an option, as could be public spending cuts or reverse QE. For me, this too is an empirical matter: my weak prior is to favour interest rates to some extent.

All of these policies, however, control inflation by depressing aggregate demand thereby tending to raise unemployment.

MMTers rightly say inflation is a constraint upon government borrowing. But it is also a constraint upon full employment.

Now, you could reject this by appealing to the idea of wage-led (pdf) growth (pdf). The prospect of continued full employment - and the wage rises and high demand it would bring with it - might encourage firms to expand capacity and invest in raising productivity. That would help hold down inflation.

We know that this has worked in the past: it did so in the 50s and 60s.

I fear, though, that it might not be so successful this time. In the 50s there was a backlog of potential investments and innovations for firms to exploit. That facilitated high capital spending and rapid productivity gains. It���s not clear we have such a backlog today.

We also know that wage-led growth ultimately failed in the 70s. There are two particular dangers here. We can call them the Minskyan and the Kaleckian.

The Minskyan one is that stability eventually begets instability. Confidence that demand will stay high could incentivize companies to over-invest thus reducing profits; or encourage banks to make ever-riskier loans; or cause share prices to rise too high. We saw all of these in the early 70s. I don���t know if Richard is right to say that higher interest rates will trigger another credit crisis. But I do suspect that he underplays the extent to which capitalism can generate crises even without significantly higher interest rates.

The Kaleckian danger is that:

Under a regime of permanent full employment, the ���sack��� would cease to play its role as a ���disciplinary measure. The social position of the boss would be undermined, and the self-assurance and class-consciousness of the working class would grow. Strikes for wage increases and improvements in conditions of work would create political tension.

As we saw in the 70s, this can lead to lower investment and hence weaker aggregate demand and rising unemployment. I suspect this will be a problem for any government seeking full employment: capitalists have got used to decades of unemployment and so would regard its absence as weird, and this alone could depress animal spirits.

There are, therefore, big obstacles to lasting full employment within a capitalist economy: a job guarantee, as I understand it, highlights these obstacles more than it overcomes them.

For me, this is why many debates about macroeconomics leave me a little cold. They miss the point that there might be severe limits, within a capitalist economy, to how much even the best policies can achieve.

February 2, 2019

My favourite economics papers

Last week Chris Bertram asked me to tweet the covers of books I���ve enjoyed, which I interpreted for the most part as books which made a big impact upon me. This set me thinking: what academic papers have also done so? Here���s a list of 11 ��� an arbitrary number, in arbitrary order, E&OE.

���The elasticity of demand with respect to product failures��� by Werner Troesken (pdf). This describes how Americans continued to buy snake oil for decades despite it being of dubious efficacy. It is of clear political relevance today: populists are using many of the tactics snake oil sellers used. But it has even wider relevance. It reminds us that whilst markets are selection devices they do not necessarily select for the best products, and can select for the worst. Bjorn-Christopher Witte���s analysis of how bad but lucky fund managers can thrive is another example of this tradition.

���Momentum��� by Narasimhan Jegadeesh and Sheridan Titman. This paper, more perhaps than any other, killed off my full confidence in the efficient markets hypothesis. Unlike many papers claiming to uncover ���anomalies���, this one has been replicated many times. I suspect that momentum, along with the out-performance of defensive stocks, are the only two robust anomalies.

���The nature of the firm��� by Ronald Coase (pdf). This is one of very few papers to have inspired an entire field of economics, and it remains hugely relevant today for analysing why firms exist at all, and why they might merge or subcontract. If you to read a coherent case for central planning, you should read this rather than anything Marx wrote.

���Can government policies increase national long-run growth rates?��� by John Landon-Lane and Peter Robertson (pdf). This made me sceptical of centrist or technocratic claims that structural reforms can boost longer-term growth: Dietz Vollrath added to my doubts.

���Depression babies��� by Ulrike Malmendier and Stefan Nagel. They shows that investors whose formative years were spent in recessions how fewer equities even years later than those who grew up in happier times. This is empirical evidence for Napoleon���s claim that ���to understand the man you have to know what was happening in the world when he was twenty.��� Our views of the world are coloured not just by current facts but by our personal histories.

���Income inequality influences perceptions of legitimate income differences��� by Kris-Stella Trump. She shows (perhaps inconsistently with Malmendier and Nagel!) that as inequality increases so too does our idea of what are fair inequalities. This means we reconcile ourselves to inequality a ��� finding corroborated by other research (pdf). We don���t need to invoke conspiracy theories or to blame the media to explain why people aren���t as radical as we would like. This is in the tradition described by John Jost ��� of how capitalism generates an ideology which helps legitimate the system. It���s also one of many examples of how modern social science has vindicated some of Marx���s claims.

���What do bosses do?��� by Stephen Marglin. This shows that the factory system originated not in a need to increase efficiency, but in bosses��� desire to better oppress workers. It reminds us that capitalism is not just about efficiency but exploitation too, and that the choice of method of production isn���t about technology alone but also about power: Skott and Guy���s nice paper is in this tradition. Marglin���s paper has been contrasted to Greg Clark���s (pdf), which argues that the factory system was in effect a way for workers to achieve a self-discipline they couldn���t otherwise get. For me, the contrast highlights two different approaches to economics ��� a study of lived experience on the one hand, against ���as if��� abstract theorizing on the other.

���Restructuring and productivity growth in UK manufacturing��� by Richard Disney, Jonathan Haskel and Ylva Heden (pdf). They show that lots of productivity growth comes not from existing plants upping their game but from entry and exit. This is consistent with the fact that financial crises have long-lasting adverse effects upon productivity: it���s because they increase credit constraints (or fears thereof) and so retard entry. It also means that if we want to increase productivity we need a healthy market economy with lots of entry and exit.

���Firm growth: a survey��� by Alex Coad. He shows that firm growth is a ���fundamentally random process��� ��� a finding consistent with that (pdf) of Chan, Karceski and Lakonishok, and with the fact that growth stocks have generally been overpriced in most stock markets. Stock-pickers, then, should remember William Goldman���s words: nobody knows anything. It might be a stretch, but this is consistent with the possibility that lots of success is due to dumb luck.

���Profit squeeze and Keynesian theory��� by Stephen Marglin and Amit Bhaduri. This addresses a paradox ��� that whilst post-war Keynesians thought high wages would add to aggregate demand and hence investment, they ended up squeezing profits and so slowing growth. For me, the paper shows that an analysis of class struggle is essential in understanding macroeconomics, but also that policies that succeed in some circumstances can fail in others.

���In search of new foundations��� by Luigi Zingales. This shows that questions such as how a firm should be financed, owned and controlled depend upon what it���s assets are ��� how important are things such as implicit contracts, intangible capital, growth options or human capital as well as physical capital. You can read it as being in the Coase-Hart-Williamson tradition of transactions cost economics. Or you can see it as more Marxian ��� as showing that technology shapes class relations.

Some of you might notice conflicts between these papers. For example, Disney et al���s finding that entry and exit ��� market forces ��� raise productivity sits uneasily with Troesken���s view that markets can select adversely. And the radical ignorance suggested by Coad is inconsistent with Jegadeesh and Titman���s finding that there are ways of picking stocks that beat the market. This, though, merely highlights a fact about the social sciences ��� that what���s true in some contexts isn���t true in others, that there are very few generally true theories. As Niels Bohr said: ���the opposite of a great truth is another great truth.���

January 31, 2019

Wishful thinking: too much, & too little

There have been several excellent tributes to the great Erik Olin Wright, which I especially urge non-Marxists to read as insights into what it means to be a Marxist today.

In a spirit of undue curmudgeonliness, however, there���s one point made by David Calnitsky I disagree with. He says:

For Marxists and fellow travelers, the power of wishful thinking is more seductive than it is for others without such normative commitments.

I disagree. We Marxists have by now learned from that most effective of teachers, the school of hard knocks, that our hopes are often disappointed. Wishful thinking is just as common ��� maybe more so ��� in other parts of the political spectrum.

This is most obviously true for many Brexiters. In July 2016 David Davis wrote:

we can do deals with our trading partners, and we can do them quickly. I would expect the new Prime Minister on September 9th to immediately trigger a large round of global trade deals with all our most favoured trade partners. I would expect that the negotiation phase of most of them to be concluded within between 12 and 24 months.

And Liam Fox famously said in 2017 that a free trade agreement with the EU should be "one of the easiest in human history."

To which I invoke Diana Ross: I���m still waiting.

It���s not just Brexiters, though, who have been guilty of wishful thinking. So too are many centrists. The idea that ���structural reforms��� can boost economic growth, or that managerialism can increase organizational efficiency, or that the right policies can stabilize macroeconomies all are all, I fear, over-optimistic.

Perhaps social democrats are also guilty. Maybe they overstate the extent to which ending austerity will restore the economy to health, and understate the extent to which capitalist stagnation has deeper causes. And maybe they exaggerate the extent to which greater equality and capitalism are compatible*.

It's not only in politics, where talk is cheap, that we find wishful thinking. We see it also in investors. A nice experiment by Guy Mayraz has shown how. He asked subjects to predict future moves in the price of wheat. Before doing so, he randomly divided them into two groups: "farmers" who would profit from a rising price, and "bakers" who would profit from a falling one. He found that farmers predicted higher prices than bakers. And they continued to do so even when they were given incentives for accurate predictions.

This is one experiment with plenty of external validity. Wishful thinking is probably one factor behind the disposition effect, the tendency for investors to hold onto losing stocks in the hope of breaking even. And it���s probably a factor behind bubbles: how much wishful thinking was there among Bitcoiners in 2017?

Wishful thinking then, is ubiquitous.

And here���s the thing. It is very often good for us. In Human Inference, one of the early books on cognitive biases, Richard Nisbett and Lee Ross wrote:

We probably would have few novelists, actors or scientists if all potential aspirants to these careers took action based on a normatively justifiable probability of success. We might also have few new products, new medical procedures, new political movements or new scientific theories.

Progress is founded upon wishful thinking. It might be that one reason for capitalist stagnation is that the tech crash of the early 00s and crisis of 2008 have depressed it.

Perhaps, therefore, our problem is that we have too much wishful thinking in politics and not enough in business.

* There���s a lot of ���maybes��� here. I���ll vote Labour in the next general election in the hope of being proven wrong, which of course might be another example of...

January 27, 2019

On backing Chavez

I was impressed to see Ian Dunt say he was wrong to have supported Hugo Chavez. Everybody makes mistakes: the difference is that some people have the insight to see that they do and the integrity to admit it.

What���s striking in this context is just how many mistakes many leftists made in supporting Chavez: I���m speaking here of all leftists, not just Ian.

I don���t just mean the common errors of wishful thinking and the ���my enemy���s enemy is my friend��� fallacy that results from the tribalism Ian decries.

What also happened was base rate neglect. Put it this way. Looking across history, what proportion of political leaders have been heroes? I doubt it���s been as high as even 1%: on the left, martyrs are more common than heroes. An application of Bayes��� theorem would therefore have told us that even if Chavez had possessed many of the characteristics of a heroic leader it would have been unlikely that he would have become one.

It is of course not just about Chavez that leftists have made this mistake. From Lenin through Che Guevara to Aung San Suu Kyi the left has done a Bonnie Tyler and held out for a hero - who tuned out to be a disappointment.

There is, however, another error at work here ��� a failure to grasp ground truth. The success or failure of a political project depends not upon its moral righteousness but upon whether material conditions on the ground permit it. You should not therefore have supported Chavez unless you had a good understanding of Venezuela���s economy and society. Which of course many leftists did not. Too many political partisans are too quick to adopt opinions without doing the necessary research ��� which is understandable as you can make a nice living writing opinion columns by doing so. (If you think this is a snark at Owen Jones alone you of course are wrong).

Heroes are scarce, but what is more common is the emergence of the right people in the right place: men (it���s usually men) of both virtues and vices who are in a position where their strengths are needed and their weaknesses are not decisive. Whether Chavez was such a man depended therefore on the precise circumstances of Venezuela���s political economy ��� something very few Brits were expert in.

Marxists, however, had good reason to be cautious about Venezuela. Marx thought the transition to socialism was most likely to occur not in middle-income nations but in advanced ones:

New superior relations of production never replace older ones before the material conditions for their existence have matured within the framework of the old society.

And in the German Ideology he wrote:

Development of productive forces...is an absolutely necessary practical premise [for communism] because without it want is merely made general, and with destitution the struggle for necessities and all the old filthy business would necessarily be reproduced.

Premature revolutions, he thought, would end in failure. This was one of his predictions he got right.

One reason for this is a paradox of inequality: vicious inequalities of the sort seen in much of Latin America make egalitarianism more desirable but also mean that it meets fiercer opposition. In an attempt to overcome this, leftist parties often become illiberal and hierarchical.

Another reason, though. Lies in a point made (pdf) by Chad Jones. It���s that poorer societies tend to be more fragile. The failure of a particular industry or even single power plant or port can do horrible damage whereas wealthier societies are better networked and more resilient (except perhaps to banking crises!) This means policy failures are much more costly. There���s less room for error. Given that leftists ��� being human ��� are likely to make errors this means the chances of failure are high.

Leftists, then, were wrong to back Chavez. But of course, the mistakes here are not confined to them. The right and centre have made them too ��� for example in thinking that shock therapy in Russia would create a liberal market economy or that the overthrow of Saddam would create peaceful liberal democracy in Iraq. And the same mix of wishful thinking and hero worship that led leftists to support Chavez has led rightists and centrists to back countless corrupt ���strong men���.

Yes, the left has been wrong. But many rightists who call them out on it are guilt of massive bad faith. As I said, everybody makes mistakes.

January 24, 2019

On top tax rates

I���m not happy with either the left or right���s conventional arguments about top marginal taxes.

Let���s take the right���s first. They claim that high taxes disincentivize the work of the highly-skilled and in doing so reduce GDP and tax revenue. I���m not happy with this because the evidence is weak (pdf). As Thomas Piketty and colleagues have shown, the feasible top tax rate could be very high indeed.

In this context, I���m baffled by Greg Mankiw���s claim that more of the rich are like Taylor Swift than Henry Potter. Let���s say Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez gets her way and there is a 70% tax rate on high incomes. What would Ms Swift do? She might leave the US for a tax haven thus depriving the IRS of revenue. But she almost certainly won���t give up making music ��� any more than George Harrison did after writing Taxman. The positive externality of her efforts (consumer surplus) will thus continue ��� as will that of all those rich who have intrinsic motivations. By contrast, it���s quite possible as Simon says that higher taxes on men like Mr Potter will reduce negative externalities such as rent-seeking, financialization or cooking a firm���s books: such men are more likely to be money-motivated and so more amenable to extrinsic incentives.

Even if I���m wrong, however, those who support Brexit must invoke an additional argument if they are to object to high taxes. Imagine a dialogue between a right-wing Brexiter and advocate to higher taxes:

Brexiter: the case for Brexit is that GDP isn���t everything. It���s worth sacrificing some income for other goals such as a greater sense of sovereignty or community.

A of higher T: Exactly, If it���s worth paying for those, why shouldn���t it be worth paying to reduce inequality?

If you���re a Brexiter opposed to higher top taxes, you have to show that greater income equality is not something worth paying for. That���s an argument about values, not merely technocratic points about GDP.

Nor, however, am I happy about standard leftist arguments for higher top taxes.

One of these is the marginal utility argument ��� that a pound is worth less to a rich man than a poor one, and so transferring it from rich to poor raises welfare.

Diminishing marginal utility, however is a more plausible story about the same person than it is about different ones. It���s true that the fourth pint tastes less good than the first. But you can���t base a political philosophy upon what happens in the Wheatsheaf. People have different utility functions. Some of the rich are rich precisely because they value the extra pound highly. If I���d had a higher marginal utility of income, I���d be richer because I���d have chosen to do less pleasant but better-paid work. (This paper (pdf) by Richard Layard and colleagues does not refute my argument, as it excludes the very rich)

There are counter-arguments to this. One is that the rich value income not because it buys them goods but because it���s a way of keeping score: the hedge fund manager wants to be richer than the manager next door. If this is the case, higher taxes don���t hurt because they bear upon all the rich: the trader at J.P. Morgan might be unhappy at paying more tax, but he can console himself with the happy thought that that bastard at Goldman���s is paying even more.

I doubt, though, that this applies to all the rich: some, I know, love their yachts and fine wines. But there���s an objection here ��� that these are acquired tastes, endogenous preferences. I find this plausible. But it confirms my argument ��� that we should not base policy upon a conception of welfare based upon subjective preferences.

The second argument I���m unhappy with is Saez and Zucman���s ��� that the justification for higher top tax rates

is not about collecting revenue. It is about regulating inequality and the market economy. It is also about safeguarding democracy against oligarchy.

It is true that the rich have excessive political influence and that high taxes on them would reduce their ability to buy politicians. But it wouldn���t go anything like far enough to reduce their power. Even if we had high top taxes there���d still be, as Adam Smith said, a ���disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful, and to despise, or, at least, to neglect persons of poor and mean condition.��� The press would still be owned by plutocrats. The BBC would still be biased. Millions of workers would face poor working conditions and petty tyrannies. Professionalism would still be under attack from managerialism. Nor would we necessarily have greater social solidarity: we might even have less if the rich resent higher taxes. Those who feel that politicians don���t listen to them might continue to feel excluded. And so on and so on.

What���s at stake here is in fact a decades-old dispute between social democrats and Marxists. Social democrats have tended to think that the unacceptable features of capitalism can be ameliorated or removed by technocratic state interventions such as appropriate tax rates. We Marxists, however, suspect that capitalism���s defects are not so easily cured.

January 19, 2019

Round pegs, round holes

An anonymous MP who met Theresa May to discuss the EU expressed their surprise at the fact that she read from a script. To this Nick Boles replied, in a wonderful example of counter-advocacy, that:

She always does that. She did the same when I had a private meeting with her to talk about the government���s housing strategy.

This highlights Ms May���s failing. When you���re engaged in multilateral negotiations ��� in which the EU is only one counterparty and perhaps not the most important ��� you need intellectual flexibility and interpersonal skills. Which is what Ms May doesn���t have. What she does have is stubbornness which is, as Simon says, ���the worst quality for a PM in the current situation.���

This is not to say that stubbornness is a bad thing. Not at all. When you are on the right course and beset by doubters and nay-sayers, it is a virtue. Sadly for Ms May and the country, this is not our current situation. It���s not that Ms May lacks qualities. It���s just that the ones she has are the opposite of those we need. To borrow Noel Gallagher���s metaphor, she's a woman with a fork in a world full of soup.

The point here goes back to Aristotle. Whether something is a virtue or vice depends upon context. In the wrong contexts, courage becomes recklessness, prudence becomes meanness, resolve becomes pig-headedness, an ability to delegate becomes laziness and so on. And in the right context, vice versa. (The skill of the obituarist consists in part in using these redescriptions.)

When you���re hiring somebody for a job, therefore, what you want is not simply the best person. You want the right person ��� one who fits the job requirement, whose strengths are those you need, and whose weaknesses won���t be shown up. Whether a hire is a success or failure will depend not merely upon their own qualities but upon the match between their own characteristics and those of their colleagues and the job requirement.

To give a few examples:

- The performance of both equity analysts and heart surgeons (pdf) varies when they change job: their success depends upon how well they fit their colleagues, not just their own qualities.

- Football managers succeed or fail depending upon how well they fit the club. Jose Mourinho is considered a failure at Man Utd, for example, in part because he was a defensive-minded coach at a team that had a culture and expectation of attacking football.

- Bosses who leave General Electric for other firms have very different results (pdf) depending on their match with the job: an engineer in a job that requires marketing skills will fail, for example.

- Winston Churchill���s pig-headed belligerence made him a liability in politics for decades. But it was just what the country needed in 1940.

Very often, though, hirers and the commentariat don���t sufficiently appreciate this They attribute success or failure to the individual when instead it is the product of the match between the individual and her environment: this is a version of the fundamental attribution error. This leads to what I���ve called cargo cult management - the idea that all will be well if only we hire the best person, whilst failing to specify the precise mechanism through which the ���best person��� will achieve results.

From this perspective, the opinion poll question ���who will make the best PM?��� is a stupid one. Nobody is perfect: everybody has weaknesses as well as strengths. What we need is not the best PM but the right one ��� one whose scant few strengths are those we need and whose many weaknesses need not be decisive.

Jeremy Corbyn, for example, has obvious weaknesses. He���s a dodgy judge of character, lazy and not intellectual. But he has virtues too, such as a common touch which Ms May lacks. (In this sense, oddly, there might be similarities with Ronald Reagan). What we should ask is whether this bag of virtues and vices is a decent fit for what the country needs. It���s not impossible that it just might be.

January 16, 2019

On the competence principle

In 1994 Stephen Young was convicted of a double murder. When it emerged that some jurors had used a Ouija board to inform their verdict, however, a retrial was ordered.

The philosophical (though not legal) justification for doing so has been described by Jason Brennan in his new book, When All Else Fails. He calls it the competence principle:

People have a right that certain types of high-stakes decisions be made by competent people, who make their decisions competently and in good faith. It is unjust, and violates a person���s rights, to forcibly deprive a citizen of life, liberty or property, or significantly harm her life prospects, as a result of decisions made by an incompetent decision-making body (p85).

Obviously, using a Ouija board to decide a man���s guilt is incompetent and thus unjust by this principle.

But here���s the thing. Brennan thinks the principle should apply not just to juries but to major policies as well:

Political decisions are presumed legitimate and authoritative only [my emphasis - CD] when produced by competent political bodies in a competent way and good faith.

If this is correct the Brexit referendum was illegitimate not (just) because it excluded big stakeholders, or was founded upon lies, or was bought with Russian money, but because the vote was taken by an incompetent electorate ��� one that was ill-informed, swayed by cognitive biases, or motivated by racism.

You might object that this is true only of some voters. Irrelevant. Only a minority of jurors in the Young case used the Ouija board.

Or you might think this is the sour grapes of a Remainer. Again, irrelevant. Young was convicted again at his retrial. The Ouija board jury got the decision right. But it���s not good enough to get it right. The competence principle says the decision must be taken in the right way.

Instead, the question is: is Brennan right? Does the competence principle actually hold?

Maybe not. In other cases of alleged incompetence by juries, law lords have refused appeals on the grounds that the need to preserve the secrecy of the jury room outweighs the competence principle. Likewise, maybe the principle is trumped in politics by another one ��� people���s right to participate. Claiming this, of course, requires reasons and not just assertions. Why should an idiot's right to a say trump other people's rights to liberty, prosperity or good government? It's not obvious to me, or to Brennan.

Even if you accept the competence principle however it does not follow at all that we should have a second referendum. There���s no reason to suppose this will be more honest or rational than the first.

Instead, the only chance of reconciling the competence principle with the right of participation (assuming one to exist, which Brennan denies) would be through some form of deliberative (pdf) democracy. This requires, among other things, tight rules on what evidence is admissible as well as safeguards against cognitive biases and inadmissible preferences.

It���s possible that such a device would deliver Brexit: as Matthew Goodwin says, people care about ���identity, community. Belonging and tradition��� as well as GDP. Or if you believe in a form of proceduralism then you���ll believe that the outcome of a truly good deliberative process will itself be legitimate.

It is of course obvious that our actually-existing media-political institutions are a trillion miles away from any ideal of deliberative democracy. This being so, the claims of both Leavers (���respect the will of the people���) and Remainers (���let���s have a second vote���) are both dubious. They beg the questions: why is the competence principle wrong? Why should we abide by decisions taken incompetently? The answer is by no means as obvious as small-minded partisans think it is.

January 15, 2019

The right's triumph; the left's complicity

If I���d told you just four years ago that I was a Remainer, you wouldn���t have known what I was talking about. The fact that we now speak about little else reveals an under-appreciated fact about politics ��� that power consists not merely in getting your own way when conflict arises, but in shaping the agenda.

Back in 2015 less than 10% (pdf) of people thought relations with the EU were the important political issue ��� far fewer than cited the NHS, economy or crime. And yet a handful of cranks have succeeded in making Brexit (a word almost unheard in 2015) dominate politics to the exclusion of all else.

In fact not only have they succeeded in transforming the agenda, but they have also changed our very identities. I couldn���t have told you I was a Remainer back in 2015 because I wasn���t: I didn���t give the EU enough thought to have it influence my perception of myself. Today, though, we are almost all Leavers or Remainers.

Most of us think of ourselves as autonomous individuals with minds of our own. And yet we have allowed others not only to determine what we talk about, but even how we identify ourselves. In this sense, we are prisoners of the right.

This is one reason why many of us on the left have been loath to engage with the day-to-day minutiae of Brexit: we are reluctant to let ourselves be defined by the cranky right.

When Corbyn said last week that:

the real divide in our country is not between those who voted to Remain in the EU and those who voted to Leave. It is between the many ��� who do the work, who create the wealth and pay their taxes, and the few ��� who set the rules, who reap the rewards and so often dodge taxes.

He was rightly expressing a frustration with the fact that the right has dominated what we talk about and how we perceive the country and ourselves.

Brexit is, however, only the biggest example of how the right shapes the agenda. In the early 2010s, the Tories persuaded even the so-called impartial media that government debt was a big economic problem when of course it wasn���t. This shaped the political agenda in a way that wouldn���t have happened if people had looked at bond markets instead of blowhards.

We see other examples almost every day. The imbecilities of narcissists such as Young, Hopkins, Morgan and the moron-speak shows on the BBC determine what gets discussed.

Very often, of course, these are utter trivialities: the latest is an advert for razor blades FFS. Only very rarely are they about how the 1% have, to a large extent, captured our political system for their own purposes. Which only vindicates what Peter Bachrach and Morton Baratz wrote (pdf) in 1962:

Power may be, and often is, exercised by confining the scope of decision -making to relatively ���safe��� issues.

Not only has the left been too passive in the face of this, it has often been complicit ��� too willing to pile into irrelevant debates chosen by the right. Too many leftists are, to some extent, sheeple.

To reinforce my point, consider the alternative ��� that you decide what issues are important not on the basis of what some idiot says but according to your own expertise and experience. Such issues might include: the adverse effects of high inequality; austerity; the decade-long stagnation in productivity and real wages; the degradation of work; the spread of managerialism to the detriment of professionalism; adverse selection mechanisms in the political-media system that promote bullshitters and idiots; a lack of deliberative democracy; a tax system that���s excessively complicated and which under-taxes land; an overly-complex and under-generous benefits system. And so on, and so on.

A good example of what I mean is James Bloodworth���s Hired: his own efforts and experience got us talking about otherwise neglected issues of poor working conditions. The problem is that it takes sustained repetition to change the agenda, not just one man���s work.

When we talk about issues chosen by the right ��� be they Brexit or immigration or the provocations of narcissists, we are not talking about other issues: there is, remember, such a thing as opportunity cost.

And this creates a bias against the left, because we are fighting on terrain chosen by the right. The fact that it is complicit in this choice of agenda is perhaps the most grievous of the BBC���s biases.

Now, there���s an obvious objection here: sometimes, we need to fight defensive battles.

This is true of Brexit ��� although we must realize (as I fear too many Remain fanatics do not) that even if Brexit is defeated the countless social, economic and political defects that contributed to it will stay in place.

I���m not so sure though, that it���s true of the endless ���calling out��� of the MorganYoungO���Neill brigade. Andrew Neil told us why when he tweeted the other day that the Spectator had gained subscriptions after Owen Jones had accused it of supporting Fascists. The problem is that a combination of biases ��� the backfire effect, attitude polarization and mere exposure ��� can cause such calling out to backfire. In attacking the Spectator Owen was giving it free publicity and causing rightists to jump to its support. It might be better ��� where possible ��� to ignore such provocations. Neil Morgan and suchlike get work because people watch them. Ignore them, and they���ll go away.

Even if I���m wrong on this, though, my main point holds. For too long, the left has been merely reactive to the right���s choice of agenda. It must become proactive and shape that agenda.

January 11, 2019

Commercialization effects in universities

Responding to students��� call for the sacking of John Finnis from Oxford University because of past homophobic writing, I tweeted yesterday that:

If I spend ��30,000 on a car I don't expect the salesman to tell me my lifestyle is unacceptable. The idea that universities should be different is a hangover from the days before tuition fees.

This needs expanding. I was not justifying the students��� demand but merely getting at a point made by Fred Hirsch back in 1976. He called it the commercialization effect. If we pay for something we have different standards and expectations than we do if we get it for free*. Motivational crowding out happens. If I���m getting something for nothing I���ll be more tolerant of any, ahem, idiosyncrasies of its suppliers than I would be if I���m spending a fortune on it. You cannot create a market in something and then be surprised when customers exercise consumer sovereignty. Economic change causes cultural change. The cash nexus might well transform what used to be a learning experience into just another paid-for leisure activity ��� and people on cruises don���t expect to be ���challenged��� or offended by the waiters,

In this context, what���s surprising is just how tolerant students still are: as Will Davies has said, the idea that they are intolerant snowflakes is a figment of the right���s imagination. This, though, might not be an immutable fact. It might merely be an example of how culture is slow to change in response to economics. Tuition fees are a sufficiently recent innovation that they have not yet crowded out traditional academic social norms about free enquiry. But they might do so eventually.

In this context, there are many issues to consider. Let���s take five.

1. There is, as Aveek Bhattacharya pointed out, a commercial transaction in which people pay to be challenged and even offended ��� personal training. Isn���t this a parallel for university? Perhaps, but the trainer���s words of admonishment are a form of roleplay: a trainer who was (improbably) sincerely racist or homophobic wouldn���t get much custom. In this sense, there���s a distinction between lecturers using thought experiments (���what���s wrong with homophobia?���) and ones expressing sincere views hostile to some students.

2. Teachers can compartmentalize. The great Andrew Glyn, for example, was never hostile to conservative students despite holding very different political views to them. Perhaps even homophobic teachers can do the same**. The converse is also true here. Lecturers with impeccably PC views in public have not always treated female students as they should: Howard Kirk wasn���t entirely a fictional character.

3. The idea that students should be challenged can easily have a class, race or gender bias in practice. Oxford vice-chancellor Louise Richardson has said that ���education is not about being comfortable. I���m interested in making you uncomfortable���. But let���s face it, it is not white public schoolboys who generally feel most uncomfortable at her institution.

4. There are different ways of challenging students. Instinctively, I���m unhappier with homophobia or racism than I am with challenging political or religious views, because the former attack students��� sense of themselves whereas the latter do not or shouldn���t: your or religious political beliefs should not be constitutive of your identity in the way your race, sexuality or gender are. But is my instinct correct? Is this distinction tenable? Adam Wagner recently tweeted that he feels ���almost physically hurt��� when liberal ideas are challenged. That suggests it mightn���t be. But this opens a slippery slope I don���t like at all: if we���re intolerant of racism, why shouldn���t we be intolerant too of conservatism?

5. What type of market is that in higher education? Some interlocutors have suggested that if students don���t like homophobic lecturers they should leave. This seems silly to me. Education is a bundle of good and bad teachers, so walking out because of one bad egg is impractical, to say nothing of the difficulty of change courses. Voice is a perfectly reasonable alternative to exit.

There are no easy answers here. My point is that in introducing tuition fees, governments threatened to change the very nature of universities. Those who attack ���snowflake��� students and who assert traditional ideas of academic freedom are guilty of ignoring basic economic realities about motivational crowding out and the commercialization effect. It might be that the strongest, and under-appreciated, argument for abolishing tuition fees is that doing is a way to protect the traditional concept of the university.

* I mean at the point of use. Students have in the past paid for their education out of taxes on their enhanced earnings.

** Finnis is retired: I���m not much interested in his particular case.

January 10, 2019

What is evidence?

By now you���ll all have seen Robert Yeh���s paper showing that there is no evidence that parachutes save the lives of people jumping from a plane. This raises a question for all social scientists: what counts as evidence? I suspect we tend to overweight some kinds of evidence, and underweight others.

Yeh���s paper is a lovely illustration of a general problem with randomized control trials ��� that they tell us how a treatment worked under particular circumstances, but are silent about its effects in other circumstances. They can lack external validity Yeh shows that parachutes are useless for someone jumping from a plane when it is on the ground. But this tells us nothing about their value when the plane is in the air ��� which is an important omission.

We should place this problem with RCTs alongside two other Big Facts in the social sciences. One is the replicability crisis. This does not afflict only psychology but other disciplines too: Campbell Harvey has said that most findings in financial economics are ���likely false���. The other (related) is the fetishization of statistical significance despite the fact that, as Deirdre McCloskey has said (pdf), it ���has little to do with a defensible notion of scientific inference, error analysis, or rational decision making��� and ���is neither necessary nor sufficient for proving discovery of a scientific or commercially relevant result.���

If we take all this together, it suggests that a lot of conventional evidence isn���t as compelling as it seems. Which suggests that maybe the converse is true. Perhaps there are some types of evidence we under-appreciate. For example:

- Non-quantitative observation. Some economists are sniffy about ���casual empiricism���. But there needn���t be anything casual about it. In sociology and anthropology ethnography is an acceptable, laudable, tradition. And it used to be in economics. Adam Smith���s work was based upon decades of observation of real people. And perhaps Coase���s The Nature of the Firm (pdf) was founded on ethnographic evidence.

- Personal experience. Just before Christmas Betsey Stevenson and Robin Hanson argued about sexual harassment. A big part of the issue was what counts as evidence: Betsey emphasised the personal experience of victims, whilst Robin emphasized thought experiments and surveys. For me, Betsey has a point. One thing I find irritating about some ���as if��� modelling is that it ignores personal experience: Greg Clark���s story (pdf) of the rise of the factory system is one example, and the idea of unemployment as arising from a taste for leisure is another.

- Memory. The Easterlin paradox ��� that economic growth doesn���t make rich societies happier - has been well challenged in statistical terms. But what lends it credence for me is not so much the statistical evidence as memory. UK GDP per head is more than 50% higher than it was 30 years ago. But are we really happier than we were then? My memory suggests not. Of course, this doesn���t prove there���s zero link between GDP and happiness, but for me it���s evidence of a weak one.

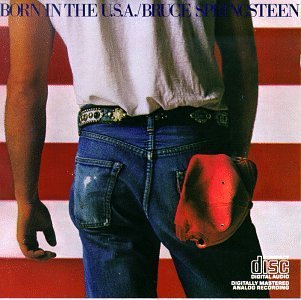

- Music. Bruce Springsteen���s album Born in the USA ��� which is now a third of a century old ��� told us that deindustrialization was linked to threats to male identity and a yearning for the past. He was years ahead of political scientists in highlighting the issues that contributed to Trump���s election. Similarly, the rise of punk in the 70s betokened harsher economic and social times; the recent popularity of drill music alerts us to the fact that inner city youth have violent lives; and the ubiquity of homesickness in old folk songs suggest urbanization was accompanied by a sense of loss. And there are countless individual songs that tell us something. To take just one example, the Pistol Annies��� Got My Name Changed Back is gloriously vivid corroboration of Andrew Clark���s finding that we adapt to traumatic events. The Boss was exaggerating when he sang ���We learned more from a three-minute record, baby, than we ever learned in school���, but he had a point.

- Literature. Eugenio Proto and colleagues have used machine reading of thousands of books to measure historic happiness. But we can of course use them less quantitatively. Surely Jane Eyre or Tess of the D���Urbervilles tell us something about the lives of real women in the 19th century.

You might object that these informal methods don���t generate proof. True. But do we need it? In finance, if you wait for proof that a strategy works before adopting it, you will buy at the top of the market. It���s entirely reasonable to act on probabilities. For example, if there���s a small chance of a disaster than can be cheaply averted, it���s wise to do so without waiting for more evidence.

In making this Feyerabendian argument for empirical diversity I am not discounting conventional scientific methods. Very often, these are vital. For example, I find the most convincing evidence that markets are prone to irrational bubbles to come from laboratory experiments (pdf) which show them to be commonplace: ���real-world��� mispricings can be explained in other ways. We should ask: what would count as evidence here? The answer will vary from context to context. I fear this trivial thought is under-appreciated.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers