Chris Dillow's Blog, page 25

December 10, 2019

The failed marketplace in ideas

The ���marketplace of ideas��� is failing. That is the message of Stefan Stern���s complaint that, in this election even more than others, lies seem to be winning.

Of course, Stefan is right to say that politicians have always been economical with the actualite. But there is, surely, a big difference between Johnson and, say, Thatcher. Whilst we lefties hated much of what Thatcher did, we only rarely thought she was lying. Being a liar was the least of Thatcher���s sins. But it is the essence of Johnson���s identity.

This was not supposed to happen. Liberals used to think that the marketplace of ideas was like other markets ��� that good products would drive out bad, that, as Mill said, ���wrong opinions and practices gradually yield to fact and argument.

But they don���t. A big reason for this is that, just as ordinary markets can fail, so too does the market in ideas. And it does so for reasons we can also see sometimes when other markets fail. Here are five such reasons.

1. Monopoly. The problem here is not merely that the press is owned disproportionately by billionaires. It is also that almost all prominent journalists (though definitely not junior ones) will be hit by Labour���s tax rises, which surely imparts a bias, or at least reinforces one. And then there���s the fact that incentives to be first with a story leads to an over-reliance upon misleading (often Tory) sources: Laura Kuenssberg���s libelling of a Labour activist yesterday fitted the pattern described by Peter Oborne. On top of this, there���s what Musa Okwonga calls ���the innate bias towards parties in power.���

Perhaps a bigger problem is that journalists, like all professionals, have their perspective distorted by their training, and indeed are selected to have such distortions. What���s especially damaging here is that they like the ���theatre of politics��� ��� the ���knockabout���, the ���who���s up and who���s down.���

This doesn���t just cause them to regard the Tories utter mess of Brexit as being drama rather than chaos. It also causes them to underweight two other perspectives.

One is these is that politics isn���t a game, but a matter of life and death ��� austerity, poverty and benefit sanctions kill. The other is that regarding politics as theatre leads journalists to think of even moderately tricky issues as ��� in John Humphrys��� words ��� as ���all getting a wee bit technical and I���m sure people are fed up to the back teeth of all this talk of stuff most of us don���t clearly understand.��� The apotheosis of this is the oft-repeated claim that Labour Brexit policy is unclear because it cannot be explained in a single word.

Of course, all of us have partial points of view. The market is ideas is healthy when these points of view collide. It becomes imperfect when one such partial point of view acquires a near-monopoly position. And this has become the case with political journalists.

2. Inadequate incentives. In theory, people should have good incentives to find best value in the market, because they���ll waste money if they don���t. Even in ordinary everyday markets, such incentives often aren���t sufficient. People waste money even on food shopping ��� and don���t get me started on fund management. This is especially true in the market for ideas. Because our individual vote doesn���t affect the outcome of elections, people have no incentive to get smart about politics. They are rationally ignorant. This is an environment in which lies can thrive.

3. Unpriced externalities. One reason why we lack incentives to know about politics is that the cost of bad decisions are borne not just by ourselves but by everybody. As Jason Brennan has said:

When a democratic majority picks a policy, this is not akin to you picking a sandwich from a menu. When the majority chooses, it chooses not only for itself, but for dissenting voters, children, foreigners, nonvoters and others who have no choice but to bear the consequence.

In this sense, a bad vote is like pollution. It imposes a cost upon everybody. And if people don���t have to pay the cost for such externalities, we���ll get too many of them.

4. Positive feedback. Conventional markets work best when there is negative feedback ��� when an unwarranted price increase leads to lower demand, thereby discouraging such increases. In the marketplace for ideas, however, we sometimes see the opposite ��� positive feedback. Barefaced lies do not lead to their teller being disgraced. Instead, they can successfully manipulate the agenda ��� for example the infamous ��350m on the side of the bus encouraged people to think about the cost of EU membership. And they can sometimes stick in the memory. As Tim Harford has written:

Repeating a false claim, even in the context of debunking that claim, can make it stick. The myth-busting seems to work but then our memories fade and we remember only the myth. The myth, after all, was the thing that kept being repeated. In trying to dispel the falsehood, the endless rebuttals simply make the enchantment stronger���Facts, it seems, are toothless. Trying to refute a bold, memorable lie with a fiddly set of facts can often serve to reinforce the myth.

In this way, the market does not drive out lies, but actually encourages them.

5. Arms races. This is true in another way. When one party gets away with lying, its opponents also resort to lies, in the same way that an athlete competing against a drugs cheat might take drugs himself simply to avoid being disadvantaged. This leads to an arms race in which both sides lie more and more. Labour is sometimes accused of lying, for example by claiming the Tories will sell off the NHS or that they will save families ��6700 a year. But its accusers fail to ask: might they be lying because they���ve learned that it pays to do so?

My point here is a simple one. There are big market failures in the market for ideas ��� bigger, perhaps, than in most markets. Ordinarily, such market failures would constitute a strong case for government intervention to mitigate them. Except that in this case, the government actually benefits from these failures. It is, therefore, difficult to see how political discourse can ever become worthwhile again.

December 4, 2019

The Tories shrinking class base

One of the great changes in public opinion during my adult lifetime has been the collapse in Tory support from younger people and the ABC1s. For example, a recent YouGov poll (pdf) found that whilst the Tories have an overall lead of nine percentage points, they trail Labour by 57%-21% among 18-24 year-olds and lead by only 39%-36% among ABC1s*. By contrast, in 1992 ��� when their overall lead was very similar - they led 54%-22% among ABC1s and trailed Labour by only three points among 18-24 year-olds.

To see the reason for this, you need only look as far as the universities��� strike. This draws our attention to another great development of recent years ��� the degradation of erstwhile middle-class work. Academics are protesting about the loss of pension rights, increased workloads, casualization and falling real pay imposed by managerialists.

And they are typical of many professionals. Journalists have suffered a massive loss of real pay and prestige in the last few decades: the best one can now hope for is to become a billionaire���s gimp. Criminal barristers, even with years of experience, make only around ��28,000 a year. And doctors are stressed out and overworked in a way that Sir Lancelot Spratt never was.

It���s not just pay and conditions which have deteriorated. Housing is now unaffordable for young graduates even on good jobs. And there is an increasing gulf between what used to be the middle-class and the richest 0.1%.

A few decades ago, a moderately successful professional had much in common with the very rich: the difference in income between them wasn���t huge; both owned property; and both enjoyed autonomy at work. But there was a huge difference between them and the working class who suffered dangerous, dirty and mind-numbing work in factories and mines.

Today, though, the opposite is the case; a 30-something professional has more in common with a contemporary working in a dull job than she does with anybody in the top 0.1%.

Very many ABC1s, then, are objectively proletarian ��� suffering from a lack of property, stagnating incomes and oppressive working conditions. And they are voting accordingly. Social grade is, increasingly, a worse way of defining class than the Marxian method of asking: what is this person���s relationship to the means of production?

This also helps explain youngsters��� antipathy towards the Tories. What���s going on here is what Alfred Hirschman called the tunnel effect. If you are stuck in a traffic jam in a road tunnel and then see a line of cars moving you cheer up, thinking that you will soon move. So it was once with young people. Back in the 80s, even poor students could reasonably look forward to a good job and property ownership. So they voted in the interests of the class they expected to join.

Today, things are different. Even bright hard-working students can expect only stressful, oppressive and poorly paid work, and to live in an over-priced hovel. And they are burdened with huge debt. Sure, much of this will be written off ��� but many young people are cursed by having a moral code which stigmatizes debt. It���s no surprise, therefore, that so many vote Labour.

All this explains why Tory support depends so much upon the legacy vote from older people and upon the populist slogan, ���Get Brexit Done���. Their historic client base has shrunk. Sure, this legacy vote and populism might be sufficient to get them over the line next week. But the Tories��� longer-term prospects are surely poor. Like Ramsay Bolton being killed by his own vicious dogs, they are being killed by the neoliberal managerialism they themselves unleashed.

* It���s a common myth that the ABC1s exclude pensioners. They don���t. They only exclude those dependent upon the state pension. Better off pensioners are classified as belonging to the social grade matching their occupation when they were working.

November 29, 2019

The power of recall

The other day, I heard the Stranglers��� Strange Little Girl for the first time in ages, prompting me to recall having an Indian takeaway in a friend���s Morris Oxford somewhere off the Clarendon Road on a sunny evening in 1982. I wonder: does this help explain why older people are more hostile to the Labour party than younger ones?

My response to that particular song was of course idiosyncratic. But it is nevertheless typical. All of us have Proustian madeleines ��� cues that prompt us to recall some memories. We all, I suspect, have songs which we associate with specific people and places. This is why ���trigger warnings��� are sometimes necessary: traumatic memories can indeed be triggered. As Daniel Levitin writes:

The brain is not like a warehouse; rather, memories are encoded in groups of neurons that, when set to proper values and configured in a particular way, will cause a memory to be retrieved and replayed in the theatre of our minds. The barrier to being able to recall everything, we might want to is not that it wasn���t ���stored��� in memory, then; rather, the problem is finding the right cue to access the memory (This Is Your Brain on Music, p165)

In a new paper Jessica Wachter shows that this process colours our financial decision-making. Take for example the finding of Erin McGuire and Stefan Nagel and Ulrike Malmendier (pdf), that economic conditions in our formative years influence how much we invest in equities even decades later. From one point of view, this seems absurd: expected returns are the same for all of us. So, how can it happen? Simple. The questions ���should I buy shares?��� or ���What is the economic outlook?��� trigger particular memories. For some, these are memories of the bear market of the 70s. For slightly younger people they are memories of the 80s bull market. And these generations invest accordingly.

A similar thing, says Professor Wachter, explains why shares fell so far ��� in hindsight by too much ��� when Lehmans collapsed. This triggered memories of (reading about) the Great Depression and hence alarm. (Luckily, though, it also reminded the Fed of the Great Depression, so it knew what not to do).

I suspect a similar process contributes to older people���s greater opposition to Labour. Remember that it is not inevitable that young people should be predominantly left-wing: in 1987, for example, more of them supported the Tories than Labour. So why are things different today?

One reason, of course, is that older people own houses and younger ones don���t.

But it could be that different memories are involved. If you are in your mid-50s or older, talk of a left-wing Labour party cues memories of the Soviet Union and of the 1970s ��� and of the more salient aspects of the 70s such as strikes rather than less salient ones such as the fact that most workers got better real-terms pay rises than they���ve had recently.

Young people, however, have none of these memories. For them, talk of nationalizing the railways trigger not memories of British Rail sandwiches but of pleasant train journeys in Europe.

Of course, the 1970s were the 1970s whether you experienced them or not. But as David Hume said, actual experiences ��� impressions ��� are stronger than mere ideas.

In one sense, all of this might be trivially obvious. In another, though, it���s not. Even though the truth should in theory be the same for all of us ��� in the way that future share price moves will be ��� we perceive it differently. This is not (just) because we are stupid or dishonest. It���s because of how memory works.

November 26, 2019

Challenging rightist illiteracy

Grace Blakeley raises an important issue, of how the Labour party can best answer the question: ���how are you going to pay for it?��� I fear that her answers, though, are a mix of the good and bad.

First, the bad. In saying that ���the arbiters of economic credibility��� claim that borrowing to invest doesn���t work, Grace is constructing a straw man. All sensible economists know, as Simon has said for years, that fiscal austerity at zero interest rates is a terrible idea.

For this reason, I disagree with Grace���s claim that mainstream economic theory ���is designed to prop up the status quo.��� Yes, this is the case in some respects, one of which I'll come to. But not in others. You can argue for fiscal expansion, liberal immigration policy, progressive taxation and even worker ownership without deviating at all from mainstream theory. Grace is right to say that the case for austerity was always political not rational ��� but mainstream theory tells us this.

I also suspect that Grace underplays the importance of the need to challenge the idea that government finances are just like the household���s, as Yanis Varoufakis tried to do here. The essence of politics is that there are failures of collective action. Sometimes, when each individual pursues her own interests, the outcome is bad for everyone; this is what happens when the government acts like a household. It���s this that provides a place for government action. The left must always make this argument.

But, but, but. Grace is bang right to say:

Working people are the ones who create the wealth, and that wealth should be returned to them.

You don���t need to believe the labour theory of value to believe this (though perhaps you should!) If working people don���t create wealth, capitalists would love to see strikes as they could carry on creating wealth without having to pay pesky workers. But of course, they don���t.

Nor is this even a left-wing view: once upon a time, It was believed by mainstream politicians.

In this sense, the left must reverse the rhetorical trick that the right has played for decades, of pretending that only entrepreneurs and the rich are ���wealth creators���. They are not.

That said, I���m not sure that this leads only to a case for taxing the rich. The ONS estimates that the top 1% of the population get 7.1% of total household disposable income. Even if you could halve that ��� which is a big ask ��� you���d raise only ��50bn. Instead, I suspect it���s also a case for greater worker ownership and control.

The issue here is a bigger, more general one: how does the left remove from public opinion the influence of the right���s economic illiteracy? Obviously, we cannot rely upon the mainstream media. And I doubt that hurried conversations on doorsteps with ill-tempered voters are sufficient.

It���s here, though, that Corbyn���s greatest achievement and legacy might lie. In motivating thousands of people to join Labour and become politically active, he has created the possibility of the left achieving hegemony via millions of everyday conversations in workplaces, pubs and cafes. Obviously, this hasn���t yielded fruit yet. It might take decades, just as it took decades for neoliberalism to eclipse social democracy. But there is this hope. And this is why I can���t regard Corbyn ��� for all his faults - with the disdain that so many others do.

November 24, 2019

Labour's corporate tax plans: a half-defence

Who really pays corporate taxes? This is the question posed by Labour���s plan to raise ��30bn (pdf) from extra taxes on companies.

These plans run into the problem that several studies have found that, ultimately, it is workers who pay a hefty chunk of such taxes. Michael Devereaux and colleagues have found that, in European countries, workers pay 92% of extra corporate taxes. A study of Germany alone has found that they pay around half (pdf) of them. And a US study (pdf) has found that they pay around one-third. A literature survey (pdf) by Ben Southwood finds that, on average, workers pay more than half of extra corporate taxes. But, he says, ���each study gives such a wide range of results over such varying sets of circumstances.���

To see why the results vary, just remember how it is that corporate taxes are shifted onto workers. It���s because, as Sam Bowman says:

Lower returns to investment means less incentive to invest in the first place. Lower investment ��� less money spent on new machinery, research and development, and other business activity ��� means lower wages and lower growth.

And there is reasonable evidence that higher (pdf) corporate taxes do indeed cut investment (pdf).

It���s for this reason that some of us would prefer that taxation be shifted onto land and away from profits.

Nevertheless, there is a possible defence of Labour.

If begins from the fact that there���s a good reason why studies find different results for the impact of corporate taxes on wages. It���s because explaining fluctuations in capital spending is really difficult because so many things influence it.

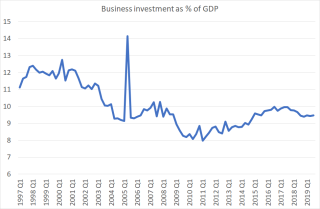

One big fact tells us this. It is that, as my chart shows*, the share of business investment in GDP is much lower now than it was in the late 90s, despite the fact that the corporation tax rate has fallen from 31% to 19% in this time (and interest rates have too). Of course, this doesn���t tell us that corporate taxes do not affect investment. But it does tell us that many other things do influence it. As Grace Blakeley has written (pdf):

The competitiveness of the business environment in a particular country depends upon a wide variety of institutional considerations. These include ���access to markets and profit opportunities; a predictable and non-discriminatory legal and regulatory framework; macroeconomic stability; skilled and responsive labour markets; and well-developed infrastructure��� (OECD 2008 (pdf)). For most types of business, these factors are considerably more important than the rate of corporation tax. This explains why Germany and France, for example, have continued to have higher levels of business investment than the UK despite much higher corporation tax rates.

What���s more, numerous factors have depressed capital spending lately.

One of these is uncertainty about Brexit.

Another is a scarring effect: the tech crash and financial crisis showed bosses that they could easily over-estimate future profits. That led to lower animal spirits.

Yet another are fears of a lack of future credit: although banks claim to be willing to lend now, firms have no assurance that credit lines will stay open during the next downturn. What���s more, as Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake have argued, businesses with large intangible assets find it difficult to raise finance because of a lack of collateral. For these reasons, firms have built up large cash piles in recent years.

And then there���s a simple lack of demand. We know that there is a ton of slack in the labour market. And the fact that inflation is low suggests there���s plenty in product markets too, all of which is reducing the need for firms to invest. As Simon says:

corporation tax plays a pretty small roll in investment decisions. The most important factor for investment in non-traded goods is the future level of demand

Herein lies a defence of Labour���s plans. It could be their other policies will boost capital spending - by reducing the chance of an economically-damaging Brexit; raising aggregate demand; and financing companies via the National Investment Bank. Yes, the medicine of higher corporate taxes have unpleasant side-effects, but Labour can treat these with other remedies.

Sadly, however, this is not certain. My concern is that neoliberalism has become performative. Decades of neoliberal ideology have taught British bosses to regard social democracy as abnormal even though it is perfectly familiar on the continent. In this way, Labour might depress animal spirits still further even though there is no logical necessity for this to be the case. If this is so, it might mean that social democratic policies are impossible, or it might mean that the job of investing can no longer be entrusted to capitalists.

* The spike in 2005 was because investment in nuclear power was reclassified then.

November 20, 2019

Ownership and productivity

In last night���s leaders��� debate, the audience laughed when Jeremy Corbyn said that productivity gains could pay for a four-day week. This is an example of what I said recently ��� that we cannot have nice things because voters have resigned themselves to the inadequacy of British capitalism.

And inadequate it is. The ONS estimates that UK productivity is one-fifth lower than that of the US, Germany or France and one-tenth lower than Italy���s. Closing some of this gap would allow for a cut in the working week with no loss of pay.

In this context, Labour���s plans (pdf) to reform corporate governance, including putting workers on boards, are crucial. John McDonnell is bang right to say that giving workers a stake in companies raises productivity: there is a ton (pdf) of evidence for this. (Which of course is wholly consistent with the likelihood that there are many other possible ways in which a government might increase productivity.)

But how can this be? One answer lies in a classic article written 30 years ago by Michael Jensen. Stock market-listed firms, he said, contain ���widespread waste and inefficiency��� because an of ���absence of effective monitoring��� of bosses by shareholders. Giving workers greater say can reduce this agency failure. This is partly because workers know the ground truth of how the company is performing better than do external shareholders. But it���s also because many workers have more skin in the game than do fund managers; whereas workers lose their jobs if the firm does badly, fund managers face less severe penalties.

At this stage, righties like to claim that the market can solve this problem.

There���s a grain of truth in this: since Jensen���s classic article, the number of stock market-quoted firms has fallen and private ownership has risen. The market cannot, however, so easily transfer companies into worker ownership in part because workers are credit-constrained.

What's more, we know for sure that product market competition does not eliminate the inefficiencies caused by agency failures. Nick Bloom and John Van Reenen show (pdf) that there is ���a long tail of extremely badly managed firms.��� And Andy Haldane has said (pdf) that ���there is a striking and widening divergence��� between the most productive firms and the rest. This would not be the case if market forces quickly drove inefficient firms out of the market.

As for what explains such differences, Haldane echoes Jensen:

(A lack of) management quality is a plausible candidate explanation for the UK���s long tail of companies���It is possible that current UK corporate governance practices may act as a brake on innovative companies.

Fans of David Graeber���s book Bullshit Jobs (of whom I am one) know one way in which bad management manifests itself. ���Managerial feudalism��� means that intermediate bosses prefer to create hierarchies of flunkeys rather than maximize profits. And inadequate oversight and imperfect competition allow them to get away with this. Graeber's is a colourful way of expressing what economists and equity investors have known for a long time ��� that companies often grow at the expense of profits.

Now, in saying all this I���m not entirely endorsing Labour���s position. My point is that companies have not been effectively pursuing shareholder value, perhaps because, as John Kay has said, such value can only be achieved obliquely. (I���m also unsure whether short-termism is a problem.)

What I am saying, though, is that the notion that changing ownership might increase productivity is far from risible. There���s tons of evidence that it can do so, and mainstream economists agree that there are failures of management and ownership: Jensen, Haldane and Bloom are not Marxists.

The fact that an audience can laugh at Corbyn���s claim to raise productivity, therefore, tells us nothing about Labour policy. But it speaks volumes ��� and damning volumes at that ��� about a political discourse that has become so debased as to put discussions about productivity outside of mainstream politics.

November 17, 2019

Why we can't have nice things

We can���t have nice things. That���s the message of Ed Davey���s speech yesterday, in which he called for a structural current budget surplus and denounced Labour���s spending plans as ���fantasy economics���. Voters seem to agree. Although many individual Labour policies are popular, the majority think Labour���s plans are unaffordable, and very few trust Corbyn on the economy.

From one perspective, all this is wrong. Over the last 25 years, two big things have changed.

One is that real risk-free interest rates have slumped. This means government borrowing and investment is much more affordable than it used to be. Governments should therefore be investing more, especially where (as with fibre broadband) the private sector is not doing so sufficiently. The failure of private sector capex to respond to ultra-low interest rates vindicates Keynes��� point:

It seems unlikely that the influence of banking policy on the rate of interest will be sufficient by itself to determine an optimum rate of investment. I conceive, therefore, that a somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment will prove the only means of securing an approximation to full employment.

Secondly, we used to think that the Nairu was high, so that increased aggregate demand would swiftly lead to higher inflation. But this is no longer the case. Even if it exists at all, the Phillips curve is quite flat, and anyway there is much more slack in the labour market than headline unemployment numbers suggest. Inflation, then, is less of a constraint on public spending than it used to be.

Economics, then, says governments can and should borrow more.

So why do so many people think otherwise?

There are legitimate objections to Labour���s plans. The party seems to have underestimated the annual cost of free broadband, and is ignoring the fact that some local providers of fibre to the door are doing a decent job. But these, I suspect are technical matters which can be sorted out.

Also, although ���where���s the money coming from?��� is the stupidest question in the world, ���where are the workers coming from?��� is not. Even though there is lots of aggregate slack in the labour market, specific shortages of doctors and engineers could stymie Labour���s ambitious spending plans. Again, though, I���m not sure this is a decisive objection: such shortages can be overcome with freedom of movement.

Instead, I suspect animus to Labour���s plans are founded ��� at least in part - in less rational considerations.

What we have here might be yet another example of what I���ve called good ideas going bad. The belief that a big fiscal expansion would run into trouble was reasonable once. But people often hold onto ideas long after they���ve ceased to be valid. One reason for this, as researchers such as Erin McGuire and Ulrike Malmendier (pdf) have shown, is that our ideas are formed in our youth and we stick to them even when their empirical base has vanished.

Secondly, there���s a halo effect. There are good reasons to worry about Mr Corbyn���s judgment; his support for the Palestinian cause has led him to some regrettable associations. Such misgivings can easily spill over into distrust of him on other issues.

Thirdly, centre-right politicians have for years played a rhetorical trick. They have invited us to believe that ���tough��� talk about ���hard choices��� is a sign of economic competence. But as Simon says. it isn���t. Sometimes, a hard heart is a sign of a soft head.

Finally, there is resignation. Frederic Jameson (or Mark Fisher or Slavoj Zizek) said that it is easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism ��� or even, I���d add, a transition to moderate social democracy. He had a point. Research shows that people resign themselves to poverty and inequality, and so stop imagining that a better world is possible.

One thing that reinforces this is cynicism. People have stopped believing that politicians can create a better world.

Another reinforcer is deference. Adam Smith was right:

The great mob of mankind are the admirers and worshippers, and, what may seem more extraordinary, most frequently the disinterested admirers and worshippers, of wealth and greatness.

Even the most incompetent and parasitic monopolist will therefore find vocal defenders.

Now, here I part company with many on the left who like to blame media bias. Yes, this might well amplify these sources of hostility to Labour���s economic plans. But as Daniel Kahneman showed, people often go wrong without any prompting from the media. Cognitive biases matter in politics, as they do in all other walks of life.

November 14, 2019

Bad faith arguments

One feature of this election campaign is that we are seeing more bad faith arguments. By this, I mean arguments which their advocates cannot sincerely believe, at least not without humungous inconsistency with their other beliefs.

One egregious recent example of this was John Redwood���s claim that Brexit is an opportunity for us to ���develop policies to rebuild our self-sufficiency in temperate food.��� It is obviously absurd that someone who claims to support free markets ��� the essence of which is the division of labour ��� should suddenly favour North Korean-style Juche. But Redwood doesn���t sincerely believe this. He���s looking for an upside to Brexit and is clutching at straws (literally?). It���s a bad faith argument.

Here are some other examples.

���Labour���s call to abolish hospital car park charges is regressive, as it���ll benefit richer people who tend to drive.���

This misses the point. It���s absurd to means-test every transaction: barmen don���t ask to see how much you earn before deciding how much to charge you for a pint. Progressiveness or regressiveness should be judged at the level of the system as a whole, not for individual actions.

Which is why I say it���s bad faith. Those making this claim aren���t saying that, taken as a whole, Labour���s policies are insufficiently redistributive. They are just looking for a flaw in Labour���s policy and missing it.

���Labour shouldn���t scrap private schools: it should raise the standard of state schools.���

Simple maths shows the problem here. Average spending on state secondary school pupils is ��6200 (pdf) per head. To raise spending to the level of that at a decent private school (say, Oakham) would need an extra ��15,000 per pupil. Across 3.2 million (pdf) pupils, this implies extra spending of almost ��50bn a year. That���s equivalent to a raising income tax by a quarter or VAT by one-third. And this is without considering the practical difficulties of giving each state school an Olympic-sized rowing lake as they have at Eton.

Nobody, though, is advocating such a spending increase. Nor are they identifying such massive inefficiencies in the state sector that the elimination of them could get pupils as well educated on ��6200 a year as ��21,000*. Which is why I say this is a bad faith argument.

���Labour���s plans for worker ownership are the confiscation of shareholders��� property.���

The people arguing this, however, take a very partial attitude to shareholders��� rights. Political uncertainty ��� about Brexit and Trump���s trade war ��� is depressing share prices and costing investors��� billions of pounds; we know this because there���s a strong correlation between the Baker, Bloom and Davis index of political uncertainty and equity valuations. If you think Labour is attacking shareholders without being equally vocal about the damage done by Trump and Brexit, you are guilty of bad faith.

���We must respect the will of the people on Brexit.���

The will of the people, however, is to retain free movement. Which argues for only the softest type of Brexit. Supporters of Johnson���s plan ��� which he himself doesn���t understand ��� cannot, therefore, easily invoke the will of the people.

What���s more, the majority of voters favour nationalizing the railways, a wealth tax, worker-directors and higher taxes on top incomes. I haven���t heard Jacob Rees Mogg calling for these. Invoking the ���will of the people��� when you do it so partially is bad faith**.

���Immigration depresses wages and puts pressure on public services.���

All the evidence, however, is that it has only a tiny effect upon the wages of the low-skilled, and that EU migration is actually a net benefit for the public services. (See this pdf and the references therein.)

I call this a bad faith argument because those who are opposed to immigration aren���t motivated by economic considerations. Almost nobody says: ���I was opposed to immigration but having seen the evidence that it does no economic harm I���m now in favour of it.��� Instead, such opposition is based on non-economic factors, not all of which are racist. Trying to find an economic justification for tough immigration controls is bad faith: it misrepresents your actual beliefs.

To be clear, I am NOT saying that all arguments here are bad faith. There are valid cases to be made against Labour���s policies on private schools, car park charges and worker ownership, and in favour of Brexit and immigration controls. Not necessarily persuasive cases, but ones that deserve a hearing. So let���s hear them, and not rank dishonesty.

* Is the Michaela Community School a counter-example to my claim? I don���t know. Its exam results seem good, but can it match private schools for activities such as sport and music?

** OK, so we���ve had a referendum on Brexit but not on a wealth tax. But why not?

November 12, 2019

Mass under-employment

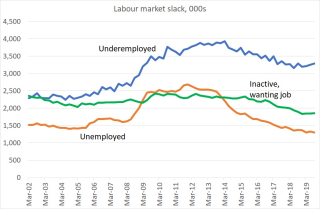

Today���s figures showed that unemployment fell slightly in the third quarter, pushing the unemployment rate down to 3.8%, its lowest since 1974. This, however, vastly under-estimates the amount of slack in the labour market.

My chart shows the point. It shows that, in addition to the 1.3m officially unemployed there are also almost 1.9m who are out of the labour force who would like a job. We know this is no idle preference; labour market flows data show that, in Q3, 547,000 people moved from inactivity into employment (and 574,000 in the opposite direction).

But there���s much more. Other data today show that, in addition to these, there are 3.3m people who are under-employed ��� who are working fewer hours than they���d like.

Put together, this adds up to 6.45 million people ��� 695,000 more that at the low-point for labour market slack seen as far back as 2005.

A big reason why there is so much underemployment is that wages aren���t high enough to provide a decent income without long hours; this is also why more people in the same household are working. As the Resolution Foundation says:

Why are so many of us working? Because we���re a lot poorer than we expected to be

From this perspective, one fact becomes explicable ��� that real wages are still lower than they were in 2007*, and that nominal wage growth has slipped back slightly recently, to 3.6% in Q3 after 3.9% in the three months to July.

This is because the under-employed put significant downward pressure on wages. Put yourself in a boss���s shoes. If the labour market is really tight, you���ll have to raise pay to get people to work more. But if you already have an employee who wants longer hours, you can get them to work more instead. You don���t need to raise pay.

Of course, the under-employed are not the only ones unhappy with their hours. ONS data show that there are 3.4 million people who���d like fewer hours even if this means low pay: this suffices to refute the silly idea that you can think of the labour market in terms of a ���representative agent���.

Such over-employment is, however, also a sign of labour market slack. It tells us that there aren���t enough jobs for people to find one with hours that suit them.

If we add together the unemployed, under-employed and over-employed we get almost ten million people who are unhappy with the world of work. That���s almost a quarter of the working age population. And this is before we mention those who are over-qualified for the jobs they are doing or who are in what David Graeber calls bullshit jobs.

This is surely a colossal systemic failure. In his book Not Working, David Blanchflower says one solution to this is for macro policy to put the pedal to the metal ��� to be much more expansionary. But I wonder: is this sufficient?

* OK, depending on how you measure price inflation.

November 10, 2019

Seeing what we expect

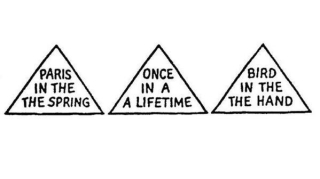

Read the words in the triangles.

Now read them again.

If you are like most people unprepared for the task, you���ll have read even these very simple sentences wrongly. You���ll have committed the mistake of seeing what you expect rather than what is there; you are so used to seeing such familiar phrases that you expect to see them even when what is actually there is a slight variation on them.

This is why it is impossible for most of us to proofread our own writing.

Not that this is always a handicap. Filling in gaps and overlooking small errors is why we can make sense of what people are saying when we can���t easily hear them because of background noise. And it���s why you all understand sentences such as ���Boris Johnson is a c*** who is talking s***���.

Sometimes, though, this can lead us astray. It is, I suspect, one reason (of several) for the momentum effect in stock markets ��� the tendency for winning stocks to carry on rising and losers to continue falling. Investors who have bought a stock and then see it suffer some bad news cleave too strongly to their prior belief that it was a good stock and so don���t sell it sufficiently strongly. This causes the share to be over-priced and so to drift down gradually later.

This is Bayesian conservatism ��� the tendency to be too conservative in updating our beliefs when we see disconfirming evidence; we see what we expect, rather than what is there. It is often underpinned by two other common biases. One is wishful thinking: we want to believe that we were right in the first place, and the wish is father to the belief. And the other is overconfidence: we exaggerate our intellectual ability and so overestimate the extent to which we are right.

Of course, this is not the only deviation we make from full rationality. Just as it���s possible to fall off a bike to the left as well as to the right, so we can make the opposite mistake of underweighting prior information. This is called base rate neglect. It is, I suspect, one reason why bosses and investors overestimate the benefits of mergers: they pay too much attention to claims about synergy, and not enough to historic evidence that such mergers often fail.

We have, though, seen two examples of the mistake of seeing what we expect recently. One is David Ornstein���s report that Arsenal���s bosses are ���100% behind Unai Emery.��� If they are sincere (and they might be), they are seeing what they expect ��� that Emery is the right man ��� rather than what the evidence shows*.

The other was Jonathan Freedland���s mistaken claim that Labour has shortlisted an anti-semite as candidate for Birmingham Hall Green. I suspect that Mr Freedland���s willingness to think of Labour as an anti-semitic party led him to infer too quickly that the Majid Mahmood they had shortlisted was the same Majid Mahmood who was an anti-semite when in fact they are different men. Had your prior been that Labour could not possibly select an anti-semite, you would have reacted to the facts ���Labour selects Majid Mahmood��� and ���Majid Mahmood was fined for anti-semitism��� by checking whether they were in fact different Mr Mahmoods. Maybe your prior was wrong, maybe not ��� but it would at least have led you to the facts.

It would be harsh to criticise Mr Freedland for seeing what he expected: this is a mistake we all make. Where he erred was in having a prior belief that so easily led to error in this case.

You might think that episode shows that centrists are not the rational evidence-based pragmatists they claim to be, but are in fact as ideological and irrational as the rest of this. I���m tempted to agree. But then in doing so I might commit exactly the same error ��� of seeing what we expect.

* There are parallels between those who wanted Wenger sacked and Brexiters: both demanded change without sufficient consideration of the effects of doing so.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers