Chris Dillow's Blog, page 23

February 21, 2020

Immigrants as scapegoats

Several observers believe that insofar as the government���s points-based immigration system reduces immigration (which as Jonathan says is ���far from certain���), it will do real economic harm. Ian Dunt says it ���is a bitterly stupid and small-hearted thing to do.��� And Anthony Painter writes:

The scale of the change and its suddenness risk very significant negative impacts. Businesses and public services could struggle to fill vacancies, seasonal businesses could especially suffer, and costs could escalate impacting business and public service viability.

These harms arise because, to the extent that the new policy is based upon economics at all, it rests upon a fallacy ��� the idea that, as Iain Duncan Smith told The World at One (20���58��� in), immigration has a ���very negative effect on earnings.���

This is plain false. The nearest thing we have to evidence for it is a paper by Stephen Nickell and Jumana Saleheen which estimates (pdf) that a ���10 percentage point rise in the proportion of immigrants is associated with a 2 percent reduction in pay.��� A 10 percentage point rise is, however, a humungous number; it���s equivalent to over three million workers across the whole economy. In reality, their estimate implies only a tiny actual effect on the earnings of the low-skilled. As Jonathan says, it suggests that:

the impact of migration on the wages of the UK-born in this sector since 2004 has been about 1 per cent, over a period of 8 years. With average wages in this sector of about ��8 an hour, that amounts to a reduction in annual pay rises of about a penny an hour.

This tallies with the general consensus, that migration has little impact on the wages of natives. A survey by the Migration Advisory Committee concluded (pdf):

Migrants have no or little impact on the overall employment and unemployment outcomes of the UK-born workforce���Migration is not a major determinate of the wages of UK-born workers. We found some evidence suggesting that lower-skilled workers face a negative impact while higher-skilled workers benefit, however the magnitude of the impacts are generally small.

This is consistent with my chart. It shows that the share of wages in GDP is higher now than it was in the mid-90s ��� despite a near-trebling in the number of foreign-born workers during this time.

It's not just in the UK that migrants don���t depress wages much. Studies of big waves of immigrants in other countries have found a similar thing. For example, the mass migration of Europeans to the US in the 1920s (pdf) ���had a positive and significant effect on natives��� employment and occupational standing, as well as on economic activity.��� And a study (pdf) of Russians��� migration to Israel after the collapse of the USSR found that it ���did not have an adverse impact on native Israeli labour market outcomes.���

The evidence then, seem clear.

But it is also counter-intuitive. Surely, if you increase the supply of something, its price will fall.

No. There���s a lot more going on than just increased supply. In some ways, migrants can boost wages.

First, they don���t just add to the supply of workers. They also add to demand. When the Polish builder spends his wages in Wetherspoons, he is adding to demand for bar staff.

Secondly, migrants are not always substitutes for native workers. They can also be complements, helping them earn more. If there���s a shortage of roofers, plasterers and electricians won���t be able to work on new houses. Importing roofers solves this problem, allowing plasterers and electricians to earn more. And if women can use cheap immigrant childcare they can go out and work longer hours.

Thirdly, migrants give natives more opportunities for management jobs. If we import a lot of fruit-pickers, who is going to oversee them? As Giovanni Peri says in a study (pdf) of Danish immigration:

An increase in the supply of refugee-country immigrants pushed less educated native workers (especially the young and low-tenured ones) to pursue less manual-intensive occupations. As a result immigration had positive effects on native unskilled wages, employment and occupational mobility.

Now, you might think these mechanisms limit the impact on natives��� wages but don���t stop it entirely. If this is the case, however, some other mechanisms operate.

One, say Banerjee and Duflo in Good Economics for Hard Times is that the reduction in wages ���makes it less attractive to adopt labour-saving technologies���, which helps sustain demand for native-born workers.

Another is that lower wages mean lower prices. That raises real incomes and hence demand for labour.

Even if all these mechanisms don���t operate, though, another would. The Bank of England would respond to lower wage inflation by cutting interest rates. And this would raise labour demand and hence wages.

And remember: locking people out of the UK will not stop them depressing wages. If migrants were to stay at home manufacturing goods on low wages, the import of these would cut natives��� wages. The factor price equalization theorem tells us that trade can reduce wages even if there isn���t a single immigrant.

Evidence and theory therefore tell us the same thing ��� that migrants do not significantly depress wages. There is, therefore, no economic justification for immigration controls.

So, why do people think otherwise? There is perhaps an analogy here with the MMR scare. Some people found it easy to believe that the MMR vaccine caused autism because there were so many stories of children having the vaccine and then being diagnosed with autism. Similarly, there are stories of migrants arriving and natives then suffering worse wages and job opportunities. In both cases, though, a simple fallacy is at work - the "after it, therefore because of it" fallacy.

In truth, though, there are other reasons for flat-lining real wages - the many failures of British capitalism which have been amplified by bad economic policy.

And herein lies the reason why Duncan Smith is so keen to claim that migrants depress wages a lot. He's simply using them as a scapegoat to deflect blame from the bigger causes of low pay.

And it is scandalously easy for him to get away with this, because the media prefers to give a platform to racists* than to educate people about economics.

* I���ll not link to that now-notorious Question Time tweet; we shouldn���t satisfy the BBC���s lust for clickbait.

February 18, 2020

Barriers to cognitive diversity

Cognitive diversity is a good thing. We need it if we are to avoid the pitfalls of groupthink, and because ��� as Hayek said ��� adequate knowledge of a complex world cannot be known to a single mind. I therefore had sympathy with Dominic Cummings call for ���weirdos and misfits��� to join Number 10.

And yet one of the first such hires has ended in failure with Andrew Sabisky���s departure following a row about his support for eugenics.

Which poses a question. Why is it so hard to achieve cognitive diversity?

In Cummings��� case one problem is simply the poverty of thought on the right. Intelligent thinking does not come from unaided individuals, but from traditions. And these traditions have withered on the right: free market economics, for example, has pretty much died. Without such moorings, original thinking can be crankery.

A comparison with Thatcher will demonstrate this. Yes, some of her coterie flirted with eugenics: Keith Joseph fretted that ���the balance of our human stock is threatened���. But such ideas were sidelined because Thatcherites had other, fish to fry. They were trying to implement an agenda inspired by Friedman, Hayek and Popper. It is a long time since the Tories had influences of similar eminence.

Cummings, though, has another problem. Pretty much nobody of genuine ability would want to take an insecure job in a city that is too expensive to live in. And nobody in their right mind wants a boss who says things like ���I���ll see half of you next Friday��� or ���I���ll bin you within weeks if you don���t fit.��� What���s remarkable, then, is not that Cummings should attract the overconfident and unemployable, but that he should have any chance at all of hiring anybody who isn���t.

But, but, but. These are not the only barriers to cognitive diversity. Ours is an age of limited intellectual breadth. Many worthwhile perspectives are rarely heard: free market pessimism; small state Keynesianism, analytical Marxism and so on. There is poverty of thought on the left as well as right ��� especially among some of those with high profiles.

One reason for this lies with our media. The BBC���s ���grid��� squeezes out too many voices and nuance, and reduces issues to simple tribal binaries. As an anonymous BBC employee has written:

Broadly speaking, there were only two types of guests for producers to choose from: Brexiteer evangelists or slick and power-hungry London Remainers. That the discussion surrounding Brexit should be conducted from these two extremes has become accepted as a sort of national truth, but it certainly doesn���t reflect the real make-up of Parliament or the country.

The point applies beyond Brexit.

Academia must also take some blame here. A friend recently showed me a rejection letter from reviewer 2, who complained that he couldn���t understand a section of the paper because it was ���purely descriptive.��� What he meant is that there are rigid rules one must follow if one is to be published, and he was damned if he was going to understand anything outside those rules. Such performative stupidity is a great recipe for groupthink. And the time academics must spend obeying those rules is time they cannot spend in more productive thought. This is one reason (of several) why the UK has suffered the near-death of the public intellectual.

There is, I regret to say, more. Those rightists who whine about the mentality that has driven Sabisky out have a point. Too many of us are sanctimonious narcissists. One of my favourite theories here was suggested by Richard Sennett back in 1970:

The threat of being overwhelmed by difficult social interactions is dealt with by fixing a self-image in advance, by making oneself a fixed object rather than an open person liable to be touched by a social situation���The jarring elements in one���s social life can be purified out���Threatening or painful dissonances are warded off to preserve intact a clear and articulated image of oneself. (The Uses of Disorder p6, 9, 11)

He was writing about the city, but his theory applies to social media too*. And it is rank hypocrisy to think this is found only on the left. The right has its own pitchfork mobs too.

Now, some of me is relaxed about Sabisky���s departure. The problem with eugenic ideas is not that they are offensive but that they are tiresomely unoriginal, unscientific and ��� for all decent purposes irrelevant. But another part of me is disquieted, because it draws attention to a big problem ��� that we lack both the institutions and culture which are necessary for proper cognitive diversity.

* One manifestation of the desire to ward off dissonances is, ironically, eugenicists need to purge undesirable elements from society.

February 14, 2020

When reputation misleads

Rebecca Long Bailey inadvertently posed a good question yesterday, when she tweeted:

Rishi Sunak the new Chancellor is a former Goldman Sachs banker who has backed anti trade union regulations; tax cuts for big business; opposing tax avoidance clampdown; cutting tax for wealthiest. The mask is slipping already, this isn���t a different kind of Tory government.

This raises the same question that is being begged by the Labour leadership contest: to what extent does a person���s past behaviour and beliefs predict their future behaviour?

We have countless examples of it not doing so. All of you will have worked with somebody who arrived at your firm with a glittering CV but who turned out to be a dunderhead, and conversely with somebody of no great reputation who turned out to be excellent. Indeed, this is pretty much the history of top-flight football managers.

Similarly, in politics, people have defied their reputations. Martin McGuinness had a history of terrorism, but he became essential to the peace process. The racist Lyndon Johnson did more for civil rights than JFK who had a liberal reputation. Theresa May arrived at Number 10 carrying hopes she would fight ���burning injustices���, just as Gordon Brown did to hopes he would be a Viking warrior, whilst Thatcher was initially an under-estimated housewife. Francois Mitterrand became president amid socialist hopes, but was soon forced to make the austerity turn. And few people in 1997 predicted that Blair would become a reckless military adventurer.

And this is not to mention the many ���future Prime Ministers��� who shrank into obscurity - who today remembers John Moore? ��� or the ministers hoping to make reforms only to ���go native��� under pressure from the Sir Humphrys.

So, why might a man���s past be an unreliable guide to his future?

Sometimes, it���s because he can use his reputation to do things that others can���t. McGuinness���s links to the IRA allowed him to persuade men to put down their arms, just as Richard Nixon���s reputation as a cold warrior gave him the political capital to seek d��tente with Russia and China.

A second reason lies in William Goldman���s eternal truth: nobody knows anything. What we know of somebody ��� especially if only by CV or reputation ��� is only a partial guide to the reality and their future. As investors in Woodford���s equity income fund know, even a good long track record is an imperfect indicator of the future.

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, we all face constraints and incentives that break the link between character and future conduct. As Marx said:

Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.

But this is not an insight confined to Marxists. Quite the opposite. Warren Buffett made the same point when he said:

When a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains.

And Charles Prince, former CEO of Citi, said the same thing when he famously said: ���as long as the music is playing, you���ve got to get up and dance.��� If incentives are strong enough, one���s past choices don���t predict one���s future ones.

Herein lies the reason why Ms Long Bailey might be wrong. Even if Mr Sunak is a head-banging inegalitarian, incentives and social structures constrain how far he can implement his desires. Acting upon his past beliefs is no way to retain the support of people who have only ���lent��� their votes to the Tories.

Now, I don���t say this with great certainty: I prefer to leave futurology to people who are paid enough to compensate them for making fools of themselves. I do so, however to flag up a danger for Labour ��� that they might be mischaracterising the Tories by painting them as simple-minded Thatcherites.

Indeed, Ms Long Bailey might be making a very anti-Marxist error ��� a version of the fundamental attribution error, of attributing too much to character and underplaying the importance of social structure.

February 12, 2020

Thatcherism's death

Thatcherism is dead. Boris Johnson���s love of big infrastructure projects conflicts with her preference for markets and caution about spending public money. His pulling out of the single market contrasts with her hailing it as ���a fantastic prospect for our industry and commerce.��� His increase in bus subsidies conflicts with her antipathy to public transport. (She never actually said that any man on a bus after the age of 30 should consider himself a failure, but the fact that it is so widely believed that she did so reveals something about her). And, of course, whereas Thatcher chose free market ideology over the wishes of northern (now post-) industrial towns, Johnson is making the opposite choice.

John Harris has quoted a senior minister as saying that ���some very prominent strands of Conservative thinking were now in retreat��� and that ���some of the things we���ve celebrated have led us astray���. Those things are Thatcherite ones.

It���s not just the political climate that is anti-Thatcherite, however. So too is much of the intellectual climate. Thatcher regularly invoked Hayek and Friedman as intellectual influences. Not only does Johnson have no such equivalents, but perhaps the two most prominent economics Nobelists today ��� Paul Krugman and Joe Stiglitz ��� are hostile to Thatcherism. And Banerjee and Duflo���s latest book, Good Economics for Hard Times, is a flat rejection of her na��ve faith in free markets, with its message that economies are sticky and slow to respond to shocks.

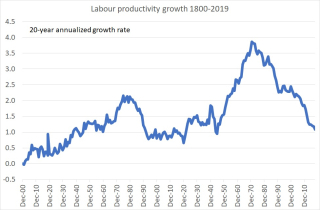

All this reflects the fact that the facts are now anti-Thatcherite. She hoped that deregulation, privatization, lower top taxes and the smashing of trades unions would lead to not just to an economic renaissance but also to a revival of what Dierdre McCloskey calls bourgeois virtues. But they haven���t. In fact, productivity growth was much slower in the Thatcherite era than it was during the post-war years. As I���ve said, there are many ways in which neoliberalism caused the productivity slowdown.

Nor have we seen a flourishing of bourgeois virtues. Thatcher hoped to create a society of men like her father, but left us one with men like her son. The assertion of ���management���s right to manage��� has led not to a healthier economy but merely to more expropriation. An under-appreciated sign of her legacy can be found on daytime TV. Programmes such as Homes Under the Hammer, Bargain Hunt and Antiques Road Trip show that the British public prefer to make money from rising house prices and selling tat rather than from graft, innovation and entrepreneurship*.

You might object here that one legacy of Thatcherism lives on - inequality. True. But of course, inequality and its defenders long pre-dated Thatcher. In many ways, what most distinguished Thatcherism is now gone.

Herein, though, lies a wonderful paradox. It is not the Conservative party that has suffered most from the death of Thatcherism. It has successfully reinvented itself, helped in part by not suffering the handicap of having principles or feeling the need to think deeply.

Instead, perhaps the biggest casualty have been centrists. The collapse of Change UK, or whatever they called themselves, means that their parliamentary presence now matches their intellectual heft. My biggest beef with them ��� and indeed with the Labour right ��� has been their total lack of any worthwhile economic ideas.

There is, I suspect, a reason for this. Centrists were keen to accept ���economic realities��� when these were Thatcherite ones of fiscal ���credibility���, tolerance of the wealth and power of the 1%, and faith that the capitalist economy could grow nicely with only little state help. Now that the realities are anti-Thatcherite ��� that inequality does real damage and that capitalism is stagnant ��� they are as helpless as a whale left on a beach after the tide has gone out.

The old jibe against the Labour right had some truth ��� that they were capitalism���s second XI. And why would anybody want a second XI when the first XI have made themselves fit for selection?

* This worked for me: most of my wealth has come from tax-free capital gains on housing.

February 7, 2020

The dangers in balance

Would balanced and impartial news and current affairs journalism be dangerous, even if it were done with maximum integrity and competence? I ask because of a recent paper by Benjamin Enke and Thomas Graeber.

We���ve known for a long time that, in the words of Glaeser and Sunstein, balanced news can produced unbalanced views. In a famous experiment (pdf) in 1979, for example, Charles Lord, Lee Ross and Mark Lepper showed people mixed reports on the effects of the death penalty and found that people who supported capital punishment became stronger in their support of it after reading them, whilst opponents of the death penalty also became more dogmatic in their opposition. Balance, then, can lead to polarization.

This mechanism, however, works on partisans ��� those who fancy themselves already informed. For those who are not informed, another mechanism can be at work, which is described by Enke and Graeber.

They call it probability compression. People who are uncertain of their own minds especially tend to treat low probabilities as if they were greater than they actually are. This is consistent with experiments (pdf) by Baruch Fischhoff and Waendi Bruine De Bruin at Carnegie Mellon University. They found that when students were asked to estimate low-probability events such as their chances of being burgled or getting cancer, they chose 50% probabilities more than they should. We also see it in gambling: punters back outsiders more than they should ��� over-rating small chances ��� and favourites (pdf) not enough. There���s a good reason why online bookies so often advertise accumulators: punters over-estimate the chance of long odds paying off. And we see it in stock markets too. Investors have paid too much for the slim chances that small speculative stocks will come good: it is partly for this reason that Aim stocks have under-performed mainline ones since their inception in the mid-90s.

Probability compression is slightly different from the tendency described (pdf) by Kahneman and Tversky for very low probabilities to be generally over-weighted. Kahneman and Tversky say we over-value small probabilities because we have a taste for long-odds bets, whereas Enke and Graeber say we over-estimate those probabilities.

It���s this mechanism that populist enemies of technocrats exploit. Michael Weiss and Peter Pomerantsev describe (pdf) how Vladislav Surkov, Putin���s eminence grise, puts forward competing stories ���not to persuade (as in classic public diplomacy) or earn credibility but to sow confusion via conspiracy theories and proliferate falsehoods.��� He is weaponizing relativism. Trump does something similar when he attacks ���fake news���. He���s not intending to establish that a story is false, merely to sow a seed of doubt. So too do climate change deniers (described well by Rebecca Long Bailey) when they claim that the ���science isn���t settled���, even though the overwhelming majority of scientists think it is.

In all these cases, people are exploiting probability compression. They suggest there is a small chance that the established narrative might be wrong, and invite listeners to over-estimate that chance.

This means that our hypothetically perfect provider of balanced news faces a nasty dilemma. On the one hand, it must present challenges to the consensus, because it is important that we avoid groupthink. But on the other hand, doing so invites people to over-estimate the small chances that the consensus is wrong.

For example, Simon has criticized the BBC for inviting Patrick Minford to discuss Brexit without telling the audience that the overwhelming consensus among economists is that Brexit would be harmful to the economy. Even if the BBC had done so, however, some of the audience would have inferred that the chance of the consensus being wrong was higher than it is.

This is all the more true because in this case (and others) probability compression is reinforced by other biases. One is a halo effect: the appeal of Brexit to many for non-economic reasons can spill over into a belief that it���s also good economics. Another is plain wishful thinking; if you want Brexit to succeed, you���ll easily persuade yourself that it will. And then there���s the familiarity effect: a falsehood you are familiar with can seem more credible than a true claim that���s not so familiar. A balanced report that repeats a false claim (perhaps if only to debunk it) can end up causing the claim to become too widely believed.

We all criticize the BBC for its failure to be properly impartial. My point here, however, goes further than this. It���s that even if the corporation were immaculately impartial it might end up inculcating false ideas. The problem with our politics, then, is not (just) bad journalism but the fact that voters can be systematically irrational.

February 5, 2020

In praise of trade frictions

Are restrictions on free trade a better idea than generally thought? I ask because, despite his lauding of it, it is reported that Johnson will impose customs checks upon goods imported from the EU. This lends credence to the estimate (pdf) by The UK in a Changing Europe that Johnson���s plan might eventually cut UK GDP by over six per cent.

But might this estimate miss an important mechanism and thus over-state the costs of us leaving the single market?

What follows cuts against all my instincts in favour of free trade and EU membership. My gut tells me to agree with Martin Wolf���s claim that Johnson���s proposals mean shooting ourselves in both feet. But we should always question our beliefs. And there is, I suspect, more to be said in favour of trade frictions than we have heard so far.

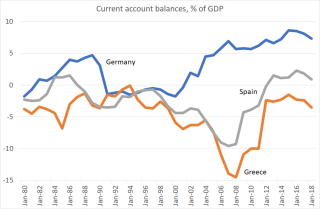

My story starts in a strange place, with the Feldstein-Horioka puzzle. This is the fact (pdf), pointed out in 1979, that net capital flows between countries are much smaller than you would imagine or, to put it another way, that current account imbalances are surprisingly small.

One reason for this is that financial markets, on their own, cannot achieve any net transfer of capital between countries This is simply because every seller needs a buyer: I can only dump my holdings of UK equities if somebody buys them. My effort to shift capital out of the UK is therefore offset by somebody else shifting it in. Instead, a net transfer of capital out of the UK requires that there be a trade surplus. This, by definition, entails an offsetting outflow of capital: if we are selling more goods and services to foreigners we are earning more than we are spending ��� ie saving, and these savings must be invested abroad.

So, what is it that limits trade imbalances and therefore current account imbalances? The answer, said Maurice Obstfeld and Kenneth Rogoff in a famous 2001 paper (pdf), are trade frictions. By these they mean not just tariffs but also non-tariff barriers such as the red tape of border checks, regulatory differences or simply customers��� preferences (pdf) for home-made goods. It���s difficult for a country to export or import a lot simply because trade costs (pdf) are high. Trade imbalances, therefore, tend to be small.

One Big Fact supports Obstfeld and Rogoff���s theory. It���s that the EU���s single market reduced trade costs - and this led to a rise in countries��� external imbalances. For example between 1980 and 1997 (when Schengen came into effect) Germany ran an annual average current account surplus of just 0.9% of GDP. Since then, though, it���s run an average surplus of 4.7% of GDP. And since 1997 the external deficits of Spain and Greece have been twice what they were in the previous 17 years.

Trade frictions, therefore, reduce current account imbalances.

Which can be a good thing. To see why, remember that a current account deficit means ��� by definition ��� that a country���s domestic investment exceeds its domestic saving. But think about what this means for its banking system. If investment exceeds savings, the growth in bank lending might well exceed the growth in deposits or the purchase of bank equity by domestic savers. Which means banks might well be becoming riskier ��� either because they are becoming more highly leveraged, or are more dependent upon wholesale funding to plug the growing gap between loans and deposits. It is for this reason that the NIESR (pdf) and Dallas Fed (pdf) have both found that big current account imbalances help predict financial crises.

The single market, therefore, might well have led to the euro crisis by fuelling greater external imbalances.

Was it really an accident that developed economies saw almost no banking crises during the Bretton Woods era, when current account imbalances were small, but saw plenty before and since?

In limiting current account deficits, then, trade frictions help preserve financial stability.

This is a great prize. Coen Teulings and Nick Zubanov have shown that financial crises lead to a huge and permanent loss of GDP. And this can be multiplied, because crises can lead to bad policy. Nick Crafts points out that the last one gave us austerity and hence Brexit. ���The economic costs of the banking crisis are much larger than is usually supposed��� he says. An important transmission mechanism here has been proven by Ben Friedman: economic stagnation, he has shown, leads to intolerance, xenophobia and anti-democratic sentiment.

Against all this is the fact that trade frictions create lots of deadweight losses. But even summed across countless goods, these can be small. So much, in fact, that Arnaud Costinot and Andres Rodriguez-Clare have estimated (pdf) that if the US were to shift to autarky it would only cost it 2-8% of GDP: for the UK, the cost would be around four times as much but for the EU much the same. As James Tobin used to say ��� rightly ��� ���it takes a heap of Harberger triangles to fill an Okun gap.��� And an Okun gap is what we get from a banking crisis.

Of course, Harberger triangles aren���t the only cost of trade frictions. There is also the fact that, in reducing competition, they retard productivity and innovation. But banking crises also do so. It���s a wash.

So, what can be said against this argument for trade frictions? I don���t think it���s sufficient to say that banks are sufficiently strong now that a crisis is unlikely. Even if this is true now, it might not remain the case in coming years. Over long enough periods, small probabilities become big ones.

Instead, you could argue that we are trading off a certain loss ��� all those Harberger triangles ��� for what is only a reduced probability of disaster. Your attitude to this trade-off will depend upon your taste for risk.

A stronger argument though is simply that there is a cheaper way than trade frictions of reducing the probability of a crisis ��� to impose higher capital requirements upon banks. But what if the power of the banking lobby prevents this?

All this suggests there might be more to be said for trade frictions than supposed. Which poses the question: why have we not heard an argument along these lines, when we have heard so many much weaker ones?

February 2, 2020

On socially influenced preferences

Some ideas are both radical and conservative at the same time. This is a thought triggered by reading Robert Frank���s latest book, Under the Influence.

���Context shapes our choices to a far greater extent than many people realize��� he writes. ���In virtually every domain, evidence suggests that our consumption patterns tend to mirror those of others in our social circle.��� He shows that behaviours such as smoking, becoming obese, committing crime (pdf) or even how many children we have are all heavily shaped by what our peers do.

This, he says, means that much of what we do imposes externalities upon others. The biggest externality of smoking, he says, is not so much the passive smoke that smokers impose upon others but the fact that their smoking encourages some others to take up the habit. This, he says, means there is an orthodox Pigovian case for taxing things like cigarettes or sugary drinks.

He goes further. There are, he says, expenditure cascades: others��� spending makes us spend more:

Higher spending at the top has shifted the frames of reference that define adequate from those just below the top, and so on, all the way down.

This, he believes, leads to a case for a progressive consumption tax.

What���s more, he thinks that opposition to higher taxes on the rich is motivated by ���the mother of all cognitive illusions���. A lot of what we buy are positional goods, such as big houses or big cars. Taxing these more heavily won���t affect their positionality, any more than would shortening a ladder change the fact that some people are on a higher rung than others.

We should, I suspect, distinguish here between behavioural externalities and informational externalities. For example, if I buy an SUV because others��� huge cars make me feel unsafe on the road in a small car, it is a behavioural externality. If, however, I buy a big car because I believe doing so is what somebody in my position should do, we have an informational externality. (The latter, I think, contribute to asset price bubbles, among other things.)

Informational externalities, says Frank, influence our political views. He cites rising support for gay marriage or the legalization of cannabis as examples: the more that others��� hold such positions, we more we are likely to see them as mainstream and so give them credence.

From one perspective, all this is unexceptional. Frank is just building on a point made by Adam Smith:

A linen shirt, for example, is, strictly speaking, not a necessary of life. The Greeks and Romans lived, I suppose, very comfortably though they had no linen. But in the present times, through the greater part of Europe, a creditable day-labourer would be ashamed to appear in public without a linen shirt, the want of which would be supposed to denote that disgraceful degree of poverty which, it is presumed, nobody can well fall into without extreme bad conduct. Custom, in the same manner, has rendered leather shoes a necessary of life in England. The poorest creditable person of either sex would be ashamed to appear in public without them.

Frank and Smith are expressing a form of cultural determinism ��� which has been a mainstream, if controversial, position in anthropology for years.

From an economist's point of view, however, it is radical. It is yet another challenge to the fiction of homo economicus, which envisages us as rational agents with exogenous preferences and beliefs. We should perhaps read Frank alongside Shiller���s Narrative Economics, which shows how our beliefs are shaped not just by facts but by stories of sometimes dubious truthfulness.

Indeed, we can push Frank���s theory a little further into much more radical territory than he explores. If our behaviour and ideas are influenced by context, why shouldn���t our identities be also? Although he never mentions it, there���s nothing in Under the Influence that contradicts Simone de Beauvoir���s claim that ���one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman��� ��� that femininity is a social construct.

And if our preferences are so endogenous, why should policy-makers attach weight to them? Pushed only slightly further, Frank���s ideas fit with Jason Brennan���s Against Democracy. And they certainly pose Daniel Hausman���s question: why satisfy preferences? (a question he answered mostly in the negative.)

We can go even further. Although Frank tries to reconcile his views on endogenous preferences with liberalism by pointing out that taxes are less restrictive than regulations, his work poses a challenge to liberalism. If our beliefs, wants and even identities are heavily socially influenced, then we are what Michael Sandel called in Liberalism and the Limits of Justice ���radically situated subjects���, and we cannot slough off our identities to go behind Rawls��� veil of ignorance. And that brings into question a foundation of liberalism.

Many of us will find Frank���s points empirically unexceptional. And yet they raise some big questions. Which reminds us that economics cannot be a merely technocratic discipline.

January 29, 2020

The bias against social science

We need the social sciences, but the media does not provide them. I say this because of a recent tweet by Frances Coppola:

If there is one thing we should learn from Auschwitz, it is that atrocities are committed by ordinary, nice people with the full support of other ordinary, nice people.

This contains an unpleasant truth, captured by Hannah Arendt���s phrase ���the banality of evil���: at least some of the perpetrators of the greatest crime in history were just very ordinary men.

But this is an extreme manifestation of a general truth, which is the essence of social science ��� that social events are not the simple product of individual character. History, said Adam Ferguson, ���is the result of human action, not of human design.��� His contemporary Adam Smith thought that the invisible hand would at least sometimes cause selfish men to act in the public interest:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.

Conversely, Marx thought that competitive forces would cause even decent capitalists to endanger their workers:

Capital is reckless of the health or length of life of the labourer, unless under compulsion from society���But looking at things as a whole, all this does not, indeed, depend on the good or ill will of the individual capitalist. Free competition brings out the inherent laws of capitalist production, in the shape of external coercive laws having power over every individual capitalist.

Smith and Marx���s disagreement hides a common idea ��� that social facts are the product of complex mechanisms, not individual character.

Indeed, very often individuals��� intentions can prove self-defeating. If everybody tries to save more, aggregate incomes fall and so we save less. If everybody tries to work longer in the hope of getting promotion, we all slog ourselves without changing our job prospects. If each individual capitalist tries to raise profits by cutting wages, aggregate demand falls thereby cutting profits. And so on.

But there���s more. Individuals��� personality and preferences are themselves at least partly socially constructed. As Robert Frank shows in his new book, Under the Influence, our behaviour and ideas are shaped by our peers. Such apparently different events as riots or stock market crashes are caused by information cascades - sometimes ones in which the blind lead the blind. We are also shaped by history. And as Ben Friedman showed and subsequent events have proven, economics also matters: hard times, at the margin, dispose people to become more intolerant, anti-democratic and nationalistic.

The task of the social sciences is to illuminate all these effects. But there is a bias against the social sciences in the media ��� a bias which is not necessarily intended or even conscious. (What was that I was saying about events not being the product of character?) I���m thinking of five separate(ish) things here:

- The news underplays slow but crucial changes. If you���re anti-capitalist you can cite the productivity stagnation as an example here; if you���re pro-capitalist, the decline in global poverty in recent decades.

- Journalists prize human interest stories. But this can efface the sociological imagination. And it can lead to a kneejerk response to any event: ���whose to blame?��� For example, the financial crisis and CEOs��� high pay are blamed on greed. This ignores the fact that almost all of us are greedy much of the time, and yet crises occur only rarely and only a few of us earn millions ��� a simple fact which tells us to look for other explanations.

- Journalists, especially perhaps on TV, try to describe what they see. But the essence of the social sciences is that there are countless mechanisms which are unseen, and invisible. To take an example from today, the BBC reports that dissatisfaction with democracy is at a record high. Public opinion can be measured and seen. But the reports tells us little about why this might be, and ignores Friedman���s important point that economic stagnation breeds anti-democratic sentiment (pdf).

- The best journalism invokes a distinction between fact and values, encapsulated by C.P. Scott���s maxim, ���comment is free, but facts are sacred." This leads to a distinction between factual reporting and opinion ��� between descriptions of what is happening and of what should happen. This distinction, though, gives too little place to the question: why is this happening? Newspapers employ too many moralists and not enough scientists.

- A concern with facts can deflect attention from mechanisms. Take, for example, the BBC headline, ���Brexit deal means �����70bn hit to UK by 2029'���. What matters here is not the precise number; this merely invites the retort: how can they possibly know that?��� Instead, what really matters are the mechanisms ��� that frictions to trade can impede growth and, worse still, gradually slow down productivity growth.

It is in these senses that we can speak of BBC bias. Bias doesn���t arise merely from bad journalism or individual ill-intent. It also does so from the fact that journalism and social science are two different things.

January 26, 2020

We don't want economic growth

In launching a new 50p coin to mark Brexit, Sajid Javid seems to be interpreting the role of Chancellor in the same spirit that Trigger regarded Del Boy���s request to talk about money: ���I saw one of those old ��5 notes the other day.��� We might have hoped that his energies would be better directed towards improving the UK���s lamentable productivity performance.

In fact, though, we should not snark. Mr Javid has grasped an important point not understood by leftists and economists (two groups which increasingly overlap) ��� that the public do not want economic growth.

We know this because they have consistently voted against it. The party of austerity won a majority in 2015; the public voted for Brexit in 2016; and they supported Johnson���s hardline Brexit deal last month even though it will reduce (pdf) GDP over time. Philip Hammond ��� remember him? ��� claimed that ���no-one voted to become poorer���. But he was wrong. They did.

It���s not just votes that tell us that people don���t want economic growth. The ONS has found that well-being has edged up since they started measuring it in 2012 despite (or maybe because of) lacklustre GDP growth.

All this is the flipside of the Easterlin paradox ��� the finding that, over long periods, rising income doesn���t increase happiness (pdf). If growth doesn���t make us happier, the lack of it shouldn���t trouble people much*.

There are, for my purposes, two things are going on here.

One is that what matters for well-being is not so much absolute income as our income relative (pdf) to our peers: if we are doing better than them, we���re happy and if we are doing worse, we���re miserable. Andrew Clark and Andrew Oswald have found that happiness depends more upon relative (pdf) income than absolute income, whilst Christopher Boyce and colleagues have found that it is a person���s position in the income ranking (pdf) that matters for their well-being, not their absolute income**.

If it is relative income we care about, then stagnation shouldn���t trouble us. We have as much chance of getting ahead of our peers when GDP is flatlining as we do when it is growing.

Also, though, economic growth is associated with some things many of us don���t like ��� with the creative destruction than runs down some industries and areas. As Banerjee and Duflo show in Good Economics for Hard Times, the economy is ���sticky���: people do not or cannot adjust to such disruption. Hence Anand Menon���s heckler���s point: ���that���s your bloody GDP. Not ours.��� A stagnant economy in which zombie firms preserve jobs and in which we face less threat from foreign competition or new technology is perfectly tolerable for many ��� and better than the tumultuous, threatening growth of the 80s and 90s.

All this helps explain the Tories��� lurch towards nativism. The problem with any policies to revive growth is that they jeopardize vested interests. This wasn���t just true of Labour policy. Stian Westlake and Sam Bowman���s proposals ��� the best I���ve seen from outside Labour ��� envisage tougher competition policy and a tax on land values. Both are threats to the Tory client base.

And why bother rocking the boat? Of course, as Benjamin Friedman showed in 2006 ��� and as subsequent events have vindicated ��� economic stagnation breeds intolerance and xenophobia. For many, however, this is not a bug but a feature.

* Yes, there are big doubts about that paradox. For my purposes, however, we don���t need to believe the coefficient of well-being on GDP is zero: a small positive one is consistent with my point.

** This isn���t to say that all income inequalities depress those at the bottom of the pile. They can make younger people happier, if they anticipate getting the high incomes themselves. Graduate trainees, for example, need not get the hump at their bosses' high earnings.

January 23, 2020

The interest rate puzzle

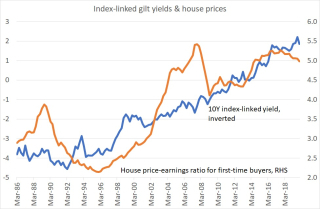

Simon points to the widespread (but not universal) consensus among economists that house prices are high because (pdf) interest rates are low. For me, this raises a puzzle.

On the one hand, this seems not just true, but trivially true. Housing is an asset. And the price of an asset should be equal to the present value of its future cashflows: rent if you���re a landlord or the rent saved if you���re an owner-occupier. Lower interest rates raise the discounted present value of future cashflows and so raise asset prices. Which is consistent with the fact that house price to income ratios have trended up as real interest rates have trended down.

But, but, but. There is one significant asset class that has not benefited from the downtrend in real interest rates ��� equities. The dividend yield (or earnings yield) on the All-share index is now much the same as it was in the early 90s despite the slump in real interest rates.

Hence my puzzle: why have lower real rates boosted house prices so much but not share prices?

An obvious possibility arises if we remember the old adage, ���never reason from a price change.��� Why have real interest rates fallen? One obvious possibility is that growth expectations have done so; low rates are the product of actual and expected secular stagnation. To the extent that this is the case, the benefits to shares of lower discount rates have been offset by a drop in expected future dividends, leaving valuations unchanged.

This, however, doesn���t get us far. For one thing, lower expected economic growth should also mean lower rents. Rental yields therefore should not have changed either.

How, then, can we explain the failure of share prices to respond as much as house prices to lower rates?

In theory, this would happen if investors fear a shift in incomes from profits to wages; in the 70s, this caused house prices to rise relative to equities. But this seems more fear than reality: for most of this century, Kaldor���s stylized fact has held for the UK: the profit share hasn���t changed much.

A more promising possibility is that the expected growth of listed companies has fallen. Today, these are older than they used to be and many might have gone ex-growth. Perhaps the best growth companies are to be found among those that aren���t on the market.

All this, though, just raises another problem: the numbers just don���t add up. Since the early 90s, we���ve seen a six percentage point drop in real interest rates. But real GDP growth cannot have fallen that much. And even if we chuck in a bit of expected redistribution away from profits and a drop in growth of quoted companies relative to unquoted ones, we must surely still be shy of six percentage points.

There���s an obvious thing which might fill this gap ��� risk. One reason why dividend yields haven���t fallen is that the equity risk premium has risen.

There are good reasons why it might have done so ��� not least being that the financial crisis reminded us that economies and markets are more volatile than we thought during the ���great moderation.���

But again, we have a puzzle. Many of the risks to equities are also a risk to house prices ��� such as the danger of recession or expropriation of exploiters. Why should equities have been more sensitive than house prices to these low-probability/high-impact dangers?

All this leaves us with three possibilities.

One is that housing was grossly under-priced in the 90s whereas equities were not, and falling interest rates have triggered a correction of that misvaluation.

A second is that both markets are worrying more about distribution risk ��� a shift from profits to wages ��� than I think.

A third is that simply that housing is over-priced.

There is a precedent for an entire asset class to become grossly misvalued when interest rates change. Back in 1979, Franco Modigliani and Richard Cohn argued (pdf) that equities were hugely under-priced because investors were discounting future cashflows by high nominal interest rates; they were taking on board the bad news of high inflation and not the good. The subsequent rebound in the market suggests they might have been right (pdf).

I wonder whether a slightly analogous thing might be happening to house prices. They are pricing in the good news of low interest rates but not the bad.

I don���t say this with huge confidence. But there is, surely, a puzzle here.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers